© Ministry of Education Malaysia, 2015.

Forewords

English Language Education Reform in MalaysiaFOREWORD

Minister of Education, Malaysia

T

he Malaysian Education Blueprint 2013-2025 highlights the need to ensure that every child is proicient in at least two languages: bahasa Malaysia and English. Fundamental to this goal is the provision of the necessary resources required for language learning, relected in the various language-based initiatives within the Malaysian education system. While the medium of instruction in our education system remains bahasa Malaysia, the Ministry of Education believes that the goal of bilingual capacity will be achieved if a concerted effort is made to upskill teachers and students in English proiciency.European Framework of Reference (CEFR) that we plan to adopt will allow us to charter our course of action in improving the English language proiciency of our students and teachers in terms of curriculum, teaching and learning as well as assessment.

The Ministry of Education as the main driver of educational innovation in the country, acknowledges the fact that change is inevitable if we intend to move with the times. We must strive to ensure that all our students are given the opportunity to realise their full potential and equip them with competitive edge skills to become global players. Change in the education system involves the introduction of new materials and pedagogies as well as the change in mind-set and attitudes. The roadmap will involve both types of changes while serving as a guiding force to impact change at all levels of education. In order for the roadmap to succeed, it is of utmost importance that all stakeholders take ownership of this plan.

I am very hopeful that this plan will succeed as it has taken a comprehensive and holistic approach that includes the whole educational spectrum right from preschool to higher education, as well as the very important lynchpin of teacher education. It is also my hope that everyone will give their undivided support to the adoption and implementation of this roadmap, just as it will be supported by the Ministry of Education.

“PENDIDIKAN ITU KEGEMBIRAAN, PENDIDIKAN ITU KEBAJIKAN, PENDIDIKAN ITU KETERBUKAAN”

FOREWORD

Minister of Higher Education, Malaysia

T

he English language plays an important role in higher education. It enables students to access information and engage in intellectualdiscourse. Its role has become even more signiicant in today’s increasingly borderless world as education becomes more globalised and

economies more multinational. This then calls for stronger and more concerted efforts by universities to equip their students with a good

command of English.

Pressure to raise student English proiciency levels is driven by the need to perform academic tasks in the language, as well as from the rapid

development of a global system of higher education. Mobility programmes and the international exchange of resources and personnel bring the world to Malaysian campuses, requiring universities to ensure that their students

are capable of communicating effectively in English.

The Graduate Employability (GE) Blueprint (2012) views universities as “the cornerstone of a country’s supply of quality and talented human

has also become an imperative role of universities in today’s complex global employment market. Universities are now expected to ensure that their

graduates are more employable by being linguistically competent in the English language.

To do so, universities need to nurture learner-autonomy and

self-directed learning for graduates to continue developing as life-long language learners. The ability to be self-aware, self-driven and independent will

stand them in good stead as entry-level employees and in the long term. A paradigm shift is thus required for undergraduates to move away

from a culture of passive formulaic learning to embracing self-directed, autonomous learning.

Thus this urgent need to develop English-proicient and self-directed graduates is being given due attention in the English Language Education

Roadmap developed by the English Language Standards and Quality Council (ELSQC). The Roadmap proposes the adoption of the Common

European Framework of Reference (CEFR) as a move to irstly, allow us to view the English proiciency levels of Malaysian graduates on an

international scale and to set appropriate targets for the next decade. Secondly, the CEFR provides a common denominator for reviewing

and aligning English Language curricula, pedagogy and assessment in universities, while still allowing individual universities to maintain their

autonomy.

YB DATO’ SERI IDRIS JUSOH

FOREWORD

Secretary-General of the Ministry of Education

I

would like to congratulate the English Language Standards and Quality Council (ELSQC) for delivering this Roadmap for English language education. The Council was commissioned to chart the way forward for the teaching and learning of English in our education system, and was given the autonomy to formulate a comprehensive plan to drive English Language Teaching (ELT) development in the country.

have a clearly focused plan for English language teaching which fully aligns with the Ministry’s language teaching policy.

Our efforts in the past have been largely directed towards the expansion of our education system to ensure equal access to education for all children from preschool to post-secondary, and tertiary level. Our concern now is on establishing and sustaining a system of high quality education that stands among the best in the region and beyond. A key factor to attaining quality education, and ensuring its sustainability, is on-going irst-rate capacity building for our teachers. Investing in our teachers is vital as we strive towards becoming a national provider of high quality English language education.

A message that comes across very clearly from the Roadmap is that a high performing education system combines equity in education with its quality. In the case of English, we have to ensure that, irrespective of gender, family background and socio-economic status, all children are

provided with an education that enables them to develop the English language skills they would need to boost their future employability, as well as their roles as responsible, productive citizens who could contribute effectively to the well-being of the nation. This is in congruence with the call to “maximise student outcomes for every ringgit spent” as expressed in the MEB 2013-2025.

I look forward to signiicant improvements in English language teaching that will follow the implementation of the Roadmap. I hope and expect that this will be an important step towards the transformation of our education system.

FOREWORD

Director-General of the Ministry of Education

Bismillahhirahmanirrahim.

Assalamualaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh.

T

he Ministry of Education Malaysia strives to ensure that Malaysian students are prof icient in both languages, namely bahasa Malaysia and the English language. This aspiration is underpinned in Shift 2 of the Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013-2025 which focuses on developing students who are at least operationally prof icient in bahasa malaysia and the English language, and at the same time providing opportunities for students to learn an additional third language. The Ministry’s aim is for all students leaving the education system to be independent users of the English language.teachers of the language in order for the plan to succeed. Alignment to the Common Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) has also made this Roadmap a more credible plan with international relevance.

The Roadmap provides comprehensive guidelines for all stakeholders to gauge the targeted proficiency levels of students from preschool right up to tertiary education. This document will serve as a guide for teachers to ensure students achieve the proficiency levels set against international standards. Students will benefit from the roadmap in which they will be equipped with the language skills to be global players and positioned to be part of the workforce in a globalised world.

It is also hoped that all initiatives encapsulated in the Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013 – 2025 and all English Language Education programmes use this Roadmap as a reference so that a concerted plan of action is carried out with respect to the teaching and learning of English in Malaysia.

I take this opportunity to thank the English Language Standards and Quality Council (ELSQC) for producing this document. It is my hope that all stakeholders involved will ensure the successful implementation of the roadmap for the betterment of our present and future generations.

.

FOREWORD

Chair of the English Language Standards and Quality Council

Bismillahhirahmanirrahim.

Assalamualaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh.

r

eforming education is an enormous undertaking. We have to start with a clear idea of what has to be done to make an improvement, and we have to ensure that the planned improvement can be carried out in practice in the real world. We also have to convince the different stakeholders – including teachers, administrators, parents, employers and the general public – that the benefits will outweigh the cost and effort involved.To create a top-performing education system, it is first necessary to create a high-calibre teaching workforce. Intending English teachers must be provided with world class education to give them not only the English proficiency, but also the content knowledge and the pedagogical skills they will need to achieve excellence in the classroom. Teachers already in post need the means to improve their proficiency, knowledge and skills, and to catch up on advances made since they were themselves trained. The point is made several times in the course of this document that teachers need support, and this is a point that cannot be made too often or too strongly.

Employers can reasonably expect the national education system to provide them with recruits who already have the basic knowledge of English they will need, and who are ready for the more speciic training required for different kinds of employment. Education administrators want a national education system of which they can feel proud, and which makes a substantial contribution to national well-being and advancement. Parents want their children to be given the English proficiency they will need to find employment and advance in their careers, and in some cases to bring their families out of poverty.

The interests of these and other stakeholders have been taken into account in the preparation of this Roadmap, and it is presented in the hope and belief that it is within our grasp to make substantial and continuing improvements in our English language education in the course of the next decade.

The most important of our stakeholders are the nation’s children. The prosperity and international standing of our country by the middle of the present century will depend in very large measure on the start in life given to the children who are already progressing through our education system or who are about to enter it. For the foreseeable future, educational success for our children will include proficiency in English.

a contribution to national advancement and the realisation of national aspirations; but the most important consideration of all is that it has been prepared for the benefit of the present generation of Malaysians and the next.

PROF. DR ZURAIDAH MOHD DON

Chair of the ELSQC

Acknowledgements

English Language Education Reform in MalaysiaT

his project was supported and funded by the Ministry of Education with the aim of creating a timetabled implementation plan for the systemic reform of English language education in Malaysia. The intended reform is part of a wider initiative to bring about the transformation of the existing English language education system not only in Malaysian schools from preschool to post-secondary, but also at tertiary level, and in teacher education.The Roadmap completes for the special case of English plans for the future of our education system that have been under development at the Ministry of Education since 2010. I would like to thank the Ministry for having the confidence in the English Language Standards and Quality Council to commission it to take the next essential step in developing English language education.

The preparation of this Roadmap has been a huge undertaking and the writing of this document has constituted an enormous amount of work. It would not have been possible without the help and support of the many bodies and individuals who have each played

their part in turning the initial inchoate ideas into a comprehensive and inclusive plan ready for implementation.

Having commissioned the Roadmap, the Ministry has given the support which is so essential to see the preparation and writing through to completion. Sincere gratitude for support goes to Dr Ranjit Singh Gill, the former ELTC Director, who participated in the initial development of this Roadmap, and to the current Director Dr Mohamed Abu Bakar, and to the Deputy Director, Pn Zainab Yusof. Among the individuals from the ELSQC Secretariat that I wish to thank are Dr Suraya Sulyman, Dr Sivabala Naidu and Pn Sarina Salim. I would like to say a special thank you to my colleagues, especially my closest collaborators, who have worked tirelessly to make success possible, and who have been admirably patient in putting up with telephone calls at unsocial hours, and carrying out essential work at short notice, or indeed no notice at all.

and reviewed by members of the ELSQC and Puan Hooi Moon Yee. The chapters submitted have been edited as far as possible, but the credit is due to the writers and the responsibility for the content of the chapters remains theirs. I also wish to thank those of my colleagues who kindly volunteered to review and improve the text, and also the former members of the ELSQC who were with me during the initial stages of the development of the Roadmap. The whole of Sections A and C, and the editorial introduction to Section B have been written centrally.

When the separate manuscripts are in, the work begins on bringing them together in the form of a coherent document. This would have been impossible on top of everyday academic responsibilities, and I was fortunate in that the last three months coincided with the beginning of my sabbatical leave. I wish to express my appreciation to the Vice Chancellor of the University of Malaya for granting me the sabbatical leave which made possible the completion of the whole document.

This document is the result of input and insights provided by numerous people, including the different stakeholders, over the last two years, who have made a substantial contribution to the shaping of the final document. Finally, I wish to thank those whose constructive feedback, critical input and continuous help and support got us through the final stages and enabled us to complete the document on schedule.

Zuraidah Mohd Don

Prof. Dr Zuraidah Mohd Don C H A I R P E R S O N

Universiti Malaya

Prof. Dr Anna Christina Abdullah PA N E L M E M B E R

Universiti Sains Malaysia

Assoc. Prof. Dr Arshad Abd Samad PA N E L M E M B E R

Universiti Putra Malaysia

Assoc. Prof. Datin Dr. Mardziah Hayati Abdullah

PA N E L M E M B E R

Universiti Putra Malaysia

Dr Kuldip Kaur Karam Singh PA N E L M E M B E R

LeapEd Services

Dato’ Dr Lee Boon Hua PA N E L M E M B E R

LeapEd Services

Ms Janet Pillai@Liyana Pillai PA N E L M E M B E R

Independent Consultant

Dr Mohamed Abu Bakar

S E C R E TA R Y

English Language Teaching Centre

Ms Sarina Salim

S E C R E TA R I AT O F F I C E R

English Language Teaching Centre

Mr Mohamed Khaidir Alias

ACTING SECRETARIAT OFFICER

Editor, Writers and Reviewers

English Language Education Reform in MalaysiaEditor, Writers and Reviewers

Chief Editor Zuraidah Mohd Don

Reviewers Zuraidah Mohd Don, Anna Christina Abdullah, Mardziah Hayati Abdullah, Arshad Abd Samad, Lee Boon Hua, Kuldip Kaur Karam Singh,

Janet Pillai, Hooi Moon Yee, Gurnam Kaur Sidhu, Choong Kam Foong, Saidatul Zainal Abidin, Lim Peck Choo, Stefanie Pillai, Hawa Rohany, Zainab Yusof, Cheok Oy Lin, Sarina Salim

Proofreaders Zuraidah Mohd Don, Hooi Moon Yee, Mardziah Hayati Abdullah, Tan Kok Eng, Chandrakala Raman, Pamela Devadason, Marina Abu Bakar, Saidatul Zainal Abidin,

Malek Baseri, Jayanthi Sothinathan, Cheok Oy Lin, Zainab Yusof, Audrey Lim Bee Yoke, Kamariah Samsuddin, Kalminder Kaur, Mohamed Khaidir Alias, Farah Mardhy Aman

Content of document Writers/Authors

Acknowledgements Zuraidah Mohd Don

Overview Zuraidah Mohd Don

Editorial Introduction Zuraidah Mohd Don to Section A

Chapter 1 Zuraidah Mohd Don

Chapter 3 Zuraidah Mohd Don, Ranjit Singh Gill, Suraya Sulyman, Sarina Salim

Editorial Introduction Zuraidah Mohd Don to Section B

Chapter 4: Preschool Anna Christina Abdullah, Tan Kok Eng, Chithra K.M.Krishnan Adiyodi,

Yeoh Phaik Kin, Regina Joseph Cyril

Chapter 5: Primary Lee Boon Hua, Mardziah Hayati

Abdullah, Aspalila Shapii, Yong Wai Yee, Chandrakala Raman, Mohamad Najib Omar, Regina Joseph Cyril

Chapter 6: Secondary Arshad Abd Samad, Hawa Rohany, Ramesh Nair, Leela James Dass, Pamela Devadason

Chapter 7: Kuldip Kaur Karam Singh, Gurnam Kaur Post-secondary Sidhu, Lim Peck Choo, Mazlina

Mohamad Aris, Marina Abu Bakar

Chapter 8: University Zuraidah Mohd Don, Mardziah Hayati Abdullah, Hooi Moon Yee, Saidatul Akmar Zainal Abidin

Editorial Introduction Zuraidah Mohd Don to Section C

The Roadmap Zuraidah Mohd Don, Anna Christina Abdullah, Lee Boon Hua, Arshad Abd Samad, Kuldip Kaur Karam Singh, Hooi Moon Yee, Mardziah Hayati Abdullah, Choong Kam Foong, Sarina Salim

Table of Contents

English Language Education Reform in MalaysiaAcknowledgements xv

English Language Standards and Quality Council xviii

Editor, Writers and Reviewers xix

Overview xxv

Section A - Context and International Standards 1

Chapter 1 - The Provenance of the English Language Roadmap 5

Chapter 2 - The Historical Background to English Language Education in Malaysia 35

Chapter 3 - The CEFR 55

Section B - Looking Back and Moving Forward 83

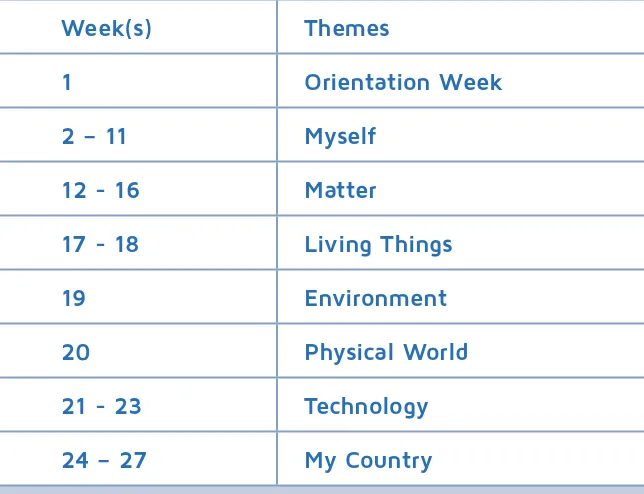

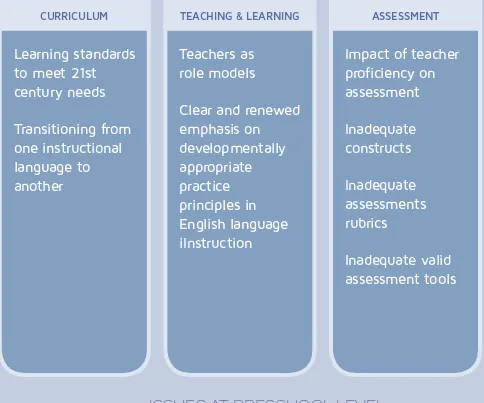

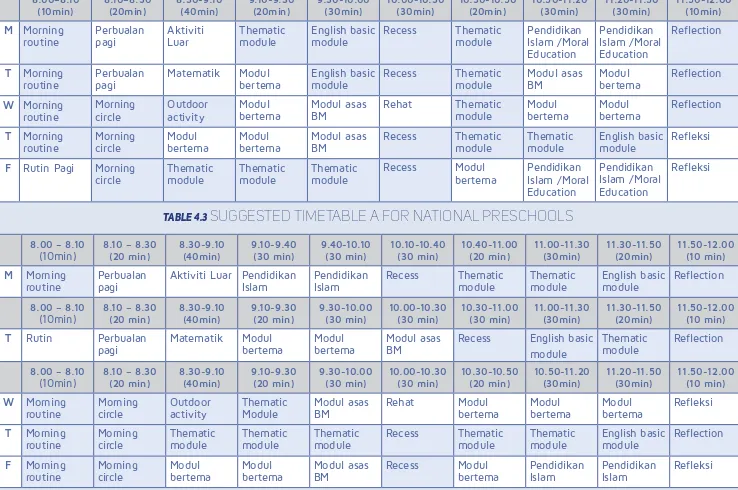

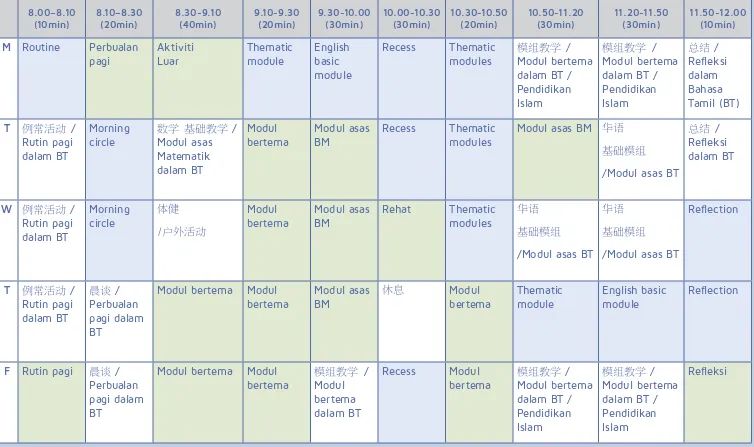

Chapter 4 - Preschool 113

Chapter 5 - PrImary 157

Chapter 6 - Secondary 189

Chapter 7 - Post-secondary 227

Chapter 8 - University 245

Chapter 9 - Teacher Education 271

Section C - The Roadmap 315

Appendices 381

Glossary 397

List of Abbreviations 403

References 409

Overview

English Language Education Reform in MalaysiaT

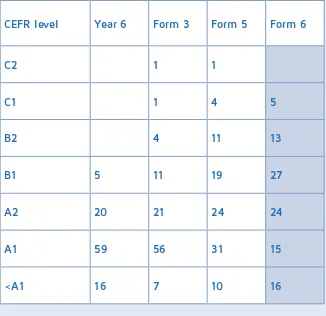

he purpose of this document is to propose a Roadmap for English Language Education from preschool to university to enable us to embark on the reform of our English language education system aligned to international standards. The Roadmap is concerned for the most part with the English language programme, which includes three components, namely curriculum, teaching and learning, and assessment. The programme is part of the wider English language education system, which includes the whole infrastructure for the teaching and learning of English. While the proposals put forward have implications for the English language education system as a whole, the only part of the system other than the English language programme that is considered in detail here is teacher education.SEC T ION

A

English Language Education Reform in MalaysiaContext and International Standards

English Language Education Reform in MalaysiaThe Roadmap 2015-2025

S

ection A introduces the Roadmap document, and sets the scene for Sections B and C.The irst chapter is concerned with what we are trying to achieve, and where we want to go. It deals with the provenance of the Roadmap itself, and picks up ideas that have long been “in the air” – such as transforming our education system and making our English language education system one of the best in the region and beyond – and shows how these ideas can potentially be turned into reality by 2025.

Chapter 2 traces the historical development of our education system, and the changing position of English within it. The chapter ends with lessons to be learned from our history, which need to be taken into account in future plans. Chapter 3 is concerned with the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (“CEFR”1), which has been selected to benchmark the performance of our current English language education system against international standards, and monitor developments in the years to 2025. The chapter includes the reasons why the CEFR is the obvious choice for Malaysia.

Looking ahead, this section summarises the many different factors and considerations that must be taken into account as we begin the task of reform. Having benchmarked the current performance in English of students and teachers from preschool to post-secondary level, we are in a position to go on to align our English language education system to international standards in the form of the CEFR. Detailed discussion of the general points raised in this section – including matters that go beyond alignment to the CEFR – are left to Sections B and C.

The Provenance of the

English Language Roadmap

1

English Language Education Reform in MalaysiaT

his opening chapter outlines the circumstances which led to the writing of a Roadmap for English language education in Malaysia. The Roadmap has been made possible by previous work which has been commissioned or undertaken by the Ministry of Education, and which enables us to complete the task of developing policy into a plan for English. This is discussed in Section 1.1, which relates our work to developments in the Ministry of Education since 2010. Section 1.2 is concerned with the connection between the reform of our English language education system and the achievement of our national goals. Section 1.3 responds to the aspiration to transform our education system, and links transformation to reform and the creation of a quality culture. The achievement of excellence in education is known to depend on excellence in the teaching workforce, and this is the topic of Section 1.4. The section that completes the chapter looks ahead to the implementation of the Roadmap.1.1 Developing policy into a plan

The Cambridge Baseline Results Report, which also appeared in 2013, investigated the present state of English teaching and learning, and provided hard evidence of where we are now in relation to the state of affairs envisaged in the MEB with respect to English. This document picks up the baton, and presents in some detail exactly what we have to do to bring our present English language education system up to the standard outlined in the MEB. The next stage is to put the plans into effect.

1.1.1 The MBMMBI policy

The Roadmap is drafted in accordance with the new language policy Memartabatkan Bahasa Malaysia Memperkukuh Bahasa Inggeris ‘to uphold Malay and to strengthen English’. The new policy took an important step forward in repositioning Malay and English as respectively the national language and the language of international communication.

The MBMMBI policy aims to uphold the rightful position of Malay not only as the national language but also as “the main language of communication, the language of knowledge, and the language for nation-building crucial towards achieving the objectives of 1Malaysia” (Ministry of Education Malaysia, 2010, p. 6). Malay is thus seen as crucial for national identity and nation-building, and as having the potential to produce its own body of knowledge.

At the same time, the MBMMBI policy strives to strengthen proficiency in English as the international language of communication and knowledge, thus enabling the exploration of knowledge so vital to compete at national and global levels. The MBMMBI policy views English as a means to empower the nation’s citizens to compete in today’s era of globalisation. This Roadmap is concerned with the English part of the MBMMBI policy, and is expected to complement a corresponding roadmap for Malay.

1.1.2 The Malaysian Education Blueprint

The MEB appeared in 2013, and is concerned with the development of Malaysian education as a whole to 2025, with the aim of transforming the existing education system and making it one of the top third of education systems in the world. It contains a brief sketch of the place of English in the wider educational plan, and this sketch has now been elaborated in the form of a plan for the reform of the English language education system (see Section C). Although the proposed reform applies specifically to English, many of the proposals apply mutatis mutandis to the teaching and learning of other languages in Malaysia, so that English has the potential to act as the trailblazer for other languages.

Reference (“CEFR”), which is mentioned briely below and discussed at greater length in Chapter 3. Having an existing framework to work with not only saves an enormous amount of time and effort, but since it has been developed over a long period of time by scholars from many different countries, we can also be conident that it will cater for our speciic needs in Malaysia.

The MEB identiies eleven fundamental shifts which need to be undertaken in order to reform the education system. Seven of these shifts – 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, and 10 – are relevant to English language education in particular, and are discussed separately in the Editorial Introduction to Section C. The programme of reform is timetabled, and is planned to be implemented in three Waves. The Waves are discussed in the Editorial Introduction to Section C, and referred to several times elsewhere in this document. In order to synchronise the reform programme outlined here with the original Waves, reference is made in Sections B and C to three “phases” which come into line with the Waves at the end of Wave 2 in 2020.

1.1.3 The Cambridge Baseline 2013

In order to apply the general education planning put forward in the MEB to the special case of English, we first have to know where we are now. We have to ascertain our starting position in order to measure the gap to be crossed by 2025. It is essential to proceed not on the basis of opinion and hearsay but as far as possible on the basis of hard evidence.

1 Part of Cambridge Language Assessment, which is itself part of Cambridge University. 2 Also informally “the baseline report” or “the baseline study”. References

unless otherwise stated are made to the Results Report.

This evidence is provided by a baseline study commissioned by the Ministry of Education and undertaken by Cambridge English1, which led to a Results Report submitted in 2013 and entitled “Cambridge Baseline 2013” (henceforth “the Cambridge Baseline”)2. This baseline study used the CEFR to evaluate the current state of English teaching and learning in Malaysia according to prevailing international standards, and assessed the proficiency of samples of students from preschool to post-secondary education, and also the proficiency of a sample of English teachers.

The comparative evaluation is known as benchmarking (see Chapter 3), and its value is that it gives us a clear idea of how our current performance matches that of other countries. The report leaves us in no doubt whatsoever that although our current English language education system may be sufficient for the needs of the past, it is not at all sufficient for us to succeed as a nation in a globalised world that requires English for international communications of all kinds.

1.1.4 The Roadmap for English Language Education

the challenge not only of global English but also of ICT which uses English as its resident language.

The reform is timely, because increasing global mobility, including developments in ASEAN, adds urgency to the need to reform our English language education system, and provide our young people from all social backgrounds, school leavers and graduates, with the means to compete successfully.

We have to create a programme that provides our young people with the English proficiency that will enable them to communicate effectively in social and professional contexts – which for those going on to tertiary education includes coping with the English requirements of their academic courses – and to find suitable employment when they complete their education, and to succeed in their careers. Our key aims are:

1. to produce an English language programme of international standard supported by a quality delivery system;

2. to make available quality English language education to all students, and as far as possible narrow or close achievement gaps irrespective of ability, gender, socio-economic background, and geographical location;

3. to produce a timetabled implementation plan or “roadmap” supported by a dedicated team to oversee its effective delivery.

Plans for reform have to begin with three fundamental questions. What are we trying to achieve? Where are we now and how did we get here? How are we going to get to where we want to be?

The first of these questions is addressed in Section A, the second is addressed with respect to the different stages of education in Section B, and the third question is addressed in Section C. We have to start with a clear idea of what we are trying to achieve and of our present position in order to coordinate and integrate the many different activities involved in the reform of our English language education system.

1.2 Creating an agenda-driven English language programme

If we are to improve the existing English language programme, we have to adopt and consistently maintain a clearly defined high level principle of organisation that guides decisions made at lower levels. The principle adopted for this Roadmap is here called agenda- driven planning, and the aim is to create an agenda-driven English language programme.

Our starting point is to observe what happens when there is no clearly defined guiding principle. It is well known, for example, that examinations have a washback3 effect on classroom teaching, and perhaps on the curriculum and even on the perceived purpose of learning. The effect of uncontrolled washback can be that the students learn very little of any real value. Teachers understandably

concentrate their efforts on getting their students through the examinations, and if the examinations do not test the right things, much of this effort is – as far as the outside world is concerned – entirely wasted.

The MEB deals at some length (pp. 4-2 – 4-4) with the three dimensions of the curriculum, namely the written curriculum, the taught curriculum and the examined curriculum, and draws attention to problems (p. 4-3) in that the (written) curriculum “has not always been brought to life in the classroom” and “examinations do not currently test the full range of skills that the education system aspires to produce”. The executive summary of the Cambridge Baseline Study also identifies a problem of this kind in Malaysian schools (p. 15).

When teachers teach for examinations, much of the curriculum not included in the examining process will be perceived as irrelevant, however well thought out and pedagogically desirable it may be. For the same reason, textbooks may be regarded as useless or irrelevant. According to the Cambridge Baseline (p. 16), 87% of teachers felt the textbook was “inadequate”. In these circumstances it is not surprising if students do not quite understand why they are learning English, or as the Cambridge Baseline puts it “lack motivation and do not recognise the importance of English for their future” (p. 8).

Figure 1.1a

The architecture of the current English

language programme- Examination-driven

Examinations

Teaching

Learning

Student

Figure 1.1b

The architecture of the current English

language programme – Curriculum-driven

Curriculum

and learning

Textbooks

materials

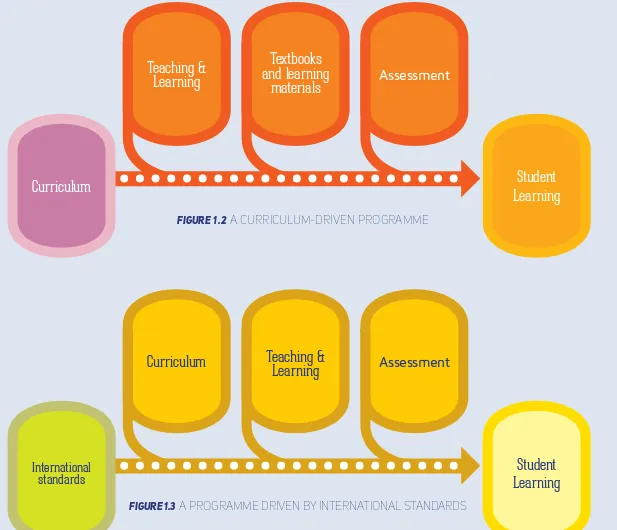

The current situation is represented in Figures 1.1a and 1.1b. (see above). The first of these represents a situation in which the examination system effectively controls what teachers do in the classroom, and ultimately what students learn. Figure 1.1b represents the relationship between curriculum and learning materials, and reflects the fact that textbook writers are required to design materials according to the curriculum.

The situation represented in the figures is found in many countries across the world, and it is by no means unique to Malaysia. The problem that immediately becomes obvious on inspection of Figure 1.1 is that examinations and curriculum do not have much to do with each other. Figure 1.1b represents what is officially going on in classrooms in principle, and Figure 1.1a what is happening in reality and in practice. No education programme can succeed with conflicting goals.

The first step is therefore to reconcile the conflicting goals. It is not possible in reality to negate the washback effect, but what we can do is to harness it, so that instead of being a source of problems, it becomes a source of strength. To do this, it is essential to take two related steps:

1. The different components of the English language programme – curriculum, teaching and learning, assessment, and teacher training – must be very closely integrated, so that all parties involved in the programme work in harmony towards the same

targets. For this to be possible, the targets must be clear and explicit, and there has to be an implementation strategy in place to make it happen.

2. The programme needs to be driven in a beneficial manner. Although the examination system is in practice the usual driver, it is not an appropriate driver and creates problems. The curriculum must be in the driving position.

This creates a new situation as illustrated in Figure 1.2 (see below).

In an integrated curriculum-driven programme, the curriculum provides teachers with appropriate content to teach at appropriate times, while textbooks and other learning materials support the teachers and the students, and forms of assessment evaluate student performance in accordance with the aims of the curriculum. It is important not to pre-judge the issue of assessment, and it must not be taken for granted that student performance is best measured by conventional examinations.

Examinations have an important place, but it must be clear what that place is, and how examinations relate to other forms of assessment. A curriculum-driven programme provides a natural focus for teacher training, which is geared towards producing teachers to contribute effectively to the programme.

Figure 1.3

A programme driven by international standards

Figure 1 .2

A curriculum-driven programme

Learning

Curriculum

Student

Learning

and learning

materials

Assessment

Curriculum

International

standards

Learning

Student

Teaching &

curriculum is designed to teach English; but the fact is that there are many different ways of teaching and learning a language. In an interconnected and globalised world, it is essential to take account of international best practice.

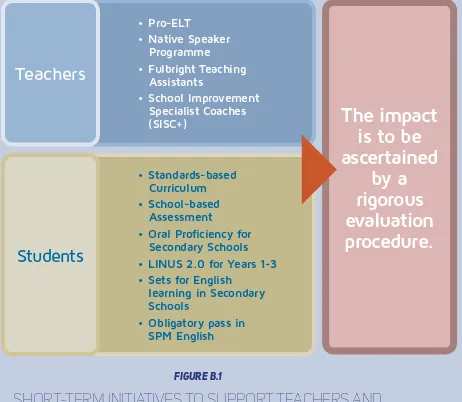

The problems that our English teachers encounter are faced by language teachers and administrators the world over. By taking the decision to use the CEFR as the guiding framework for curriculum development, we also face the challenge of international standards. The benchmarking which we have already begun evaluates our curriculum and other aspects of our English language programme according to the standards set by international best practice. International benchmarking enables us to develop our English language programme in a principled manner. This leads to a programme driven by international standards, as illustrated in Figure 1.3 (see above).

The adoption of international standards brings with it a number of advantages. For example, the use of a common framework will ensure that our programme in Malaysia is fully up to date with what is known globally about language teaching and learning and about best practice. It is difficult under present conditions for international employers or university admissions officers to evaluate examination results indicating a level of success in relation to a curriculum unique to Malaysia. Common international standards will enable an informed comparison of levels of achievement in all countries that use them. These will in practice be the standards

of the CEFR, and a further advantage of the CEFR is that we in Malaysia are fully in control of what we take from it, and how we make use of it for our own national advantage.

A further consideration in the design of the programme is people’s motivation to learn languages, and people learn languages for many different reasons. A traditional motivation is to read literature in the original language, and the study of English at university level in Malaysia was formerly closely related to the study of English literature.

Another motivation is to communicate with people in a country in which one spends a long period of time, and for many Malaysians this remains a powerful motivation to learn English. However, it would appear from the baseline study (pp. 7-8) that many Malaysians spend a lot of time learning English without quite knowing why they are doing it.

There has to be a motivation for learning English that applies equally to students from rural and urban areas, to boys and girls, and to students studying the Arts and the Sciences. This motivation comes directly from national aspirations. Malaysia has long aspired to be recognised internationally as an advanced high-income nation by 2020, and in order to turn aspiration into reality, there are certain things we have to do, which means we have to have a clearly deined agenda. For example, we need to increase the contribution to the nation of our school leavers and graduates by making them more employable4.

In the case of the English language programme, this translates into the need for graduates with sufficient English language skills to obtain suitable employment, and at a lower level for school leavers with the English proficiency necessary for jobs that require contact with English speakers. It is in the national interest to create a workforce with the necessary English language skills; but it is also very much in the interests of individual graduates and school leavers to develop these skills for themselves, whether they work for an international corporation, or serve in a shop, restaurant or hotel. Linking the English language programme to national aspirations leads to the situation illustrated in Figure 1.4. Figure 1.4

An aGENDA-driven

programme

Curriculum

International

standards

National

Aspirations

Quality student

outcomes

by 2025

Teaching &

5 Government Transformation Programme: The Roadmap. The Prime Minister’s Office, 2010.

National aspirations have already motivated the decision to benchmark our English language programme. A consequence of benchmarking is that it brings to light ways in which the curriculum needs to be modified in order to bring our English language programme fully up to prevailing international standards. The curriculum in turn drives teaching and learning, and teaching and learning together drive the development of learning materials and ultimately assessment and teacher training.

Note that in Figure 1.4, the international standards bubble is placed below the line, because being international they are not under Malaysian control. The other three, namely curriculum, teaching and learning, and assessment are placed above the line. The identification of national aspirations, along with the curriculum, teaching and learning, and methods of assessment all belong to Malaysia.

Benchmarking, by contrast, gives us information on how our provision compares with international standards, and we can use this information and exploit it to our own advantage. Although benchmarking cannot of course control what we do, it can help us decide what goes into our national curriculum in order to achieve our national aspirations.

This subsection ends with a brief summary:

1. The English language programme must be driven not by examinations but by our national agenda, which is itself based on our aspirations as a nation, and which amounts to what we as a nation want to achieve by making all our young people learn English.

2. The different components of the programme – curriculum, teaching and learning, learning materials, and assessment – must be fully integrated, and we need a strategy in place to ensure that this integration is achieved and maintained.

3. The development and implementation of the programme have to keep to the timetable outlined in the MEB in the form of Waves 1 to 3.

1.3 Bringing about transformation

A term which is currently in widespread use in the MoE is

programme of reform in the hope and expectation that it will lead to transformation (see Figure 1.5).

The national aspirations have already been established (see the MEB, p. E-1), and the review of the existing system has been undertaken by Cambridge English. The findings of the Cambridge Baseline will have to be followed up with a more detailed positive critical evaluation, the aim of which is not to destroy, but rather to identify shortcomings with a view to putting them right.

While the outcome may be negative in the short term, this is ultimately a positive process that leads to positive outcomes. In the case of English language education, we have to identify

areas in need of reform. Several such areas have been identified in the baseline study and in Section B, and they include the spoken proficiency of students and teachers, and teacher education.

Having been identified, these problem areas have to be attended to as matters of priority, for otherwise we will not carry out a worthwhile reform, we will not reach the goals set by the national agenda, and the transformation will not take place. Our task is not only to identify areas in need of reform, but also to show how reform can be implemented so that the aspiration for transformation becomes a reality.

Establishing

National

Aspirations

Reviewing

the existing

English

Language

Education

System and

Measuring its

Performance

Producing and

Implementing

a Roadmap

Transformation

of the English

Language

Education

System

Figure 1.5

Quality

Delivery

System

Quality Culture in

English Language Education

Quality

Learning

Outcomes

Quality

English

Language

Programme

1.3.1 Creating a quality culture

The mechanism of reform by means of which we can bring about transformation is the creation of a quality culture. Our English language education system must bear the hallmark of quality, which means that quality must be sustained and maintained throughout, making the system “comparable to high-performing education systems” (MEB, p. 2-2). To create a quality culture “(see Figure 1.6), we need

1. Quality in our English language programme;

2. A quality delivery system;

3. Quality in learning outcomes.

The achievement of quality in the English language programme begins with the alignment of our programme to international standards, so that we know how it compares with the rest of the world, and the rest of the world knows how to evaluate Malaysian educational qualiications. The different components of the programme need to be integrated and aligned so that the curriculum speciies the right things to be taught at the right time and in the right order, and assessments test what students have been taught and provide them with qualiications that indicate what they are able to do in English when they have left the education system. Students need to progress in a systematic fashion through the programme,

and make successful transitions from preschool to primary school and then secondary school, and perhaps on to tertiary education.

Quality in the programme itself needs to be matched by the way it is delivered to learners in the classroom. A quality delivery system includes:

1. a continuous and sufficient supply of high-calibre teachers;

2. the provision of high quality learning materials including online learning resources;

3. the creation of a high quality learning environment.

Quality would appear already to have been achieved in the selection of recruits for teaching. The MEB reports (p. 5-3) rising academic standards among applicants for teacher training, and a ratio of no fewer than 38 applicants per place. The Cambridge Baseline draws attention to the high level of commitment on the part of Malaysian English language teachers.

Quality teachers need quality tools, and these include textbooks and other learning materials of international standard, and classroom equipment to enable them to make the most effective use of class time, including where appropriate the use of ICT for teaching and learning. The time of quality teachers is a resource that needs to be well managed, and teachers should spend their time doing things that only teachers can do. For example, the introduction of school-based assessment could be undermined if teachers are already overloaded with other work, and they need to be relieved of work that could in principle be done by others. The acquisition of quality textbooks would itself relieve teachers at least in part of the need to produce basic learning materials.

A high quality learning environment is one that optimises the conditions for student learning. This includes not only textbooks and other formal learning materials, but also reading materials that the students enjoy reading, and films and other video materials that they enjoy watching. The rich environment needs to be extended beyond the classroom, so that students are exposed to English and can use English in situations relevant to their everyday lives. Parents and others with sufficient English can be actively involved in the children’s learning, and can even help in the school.

Quality in learning outcomes means that students achieve what they are capable of achieving, and no students are left behind for lack of opportunity. In accordance with the principle of equity, we have to ensure that an improved English programme

reaches all our young people, and that they are given a chance to succeed in learning English irrespective of their social background or geographical location.

Opportunity goes beyond the classroom experience, and covers the whole learning environment. Equality of opportunity for all, including rich and poor, boys and girls, and for those from urban and rural areas will not only give young people from less advantaged backgrounds a better chance in life, but also take advantage of hitherto underutilised talent and potential for the beneit of the nation.

The English Language Standards and Quality Council (henceforth “ELSQC”) has been established as the overseer of standards and quality in our English language education system. What is clearly needed is a hallmarking system for taught courses, teacher training programmes, assessments, and other ventures in the field of English language.

Such a task would require resources far beyond those of the ELSQC, and so much of the quality control would have to be delegated to bodies answerable to the ELSQC whose members have been ascertained to be of the right calibre. Procedures for assessing teachers, for example, would themselves have to be hallmarked.

investment and expenditure. We need to get value for every ringgit (MEB, p. 6-11). Hallmarking would save expenditure on poor quality ventures unlikely to lead to improvements, and concentrate spending on high quality ventures more likely to yield positive results.

1.3.2 Integration

Among the most important ingredients of quality is integration. All the different components have to work together as a single integrated functioning system. Decisions taken at one stage have consequences for decisions to be taken further downstream. The MBMMBI policy leads to the MEB, and the MEB leads to the commissioning of this Roadmap. The Roadmap needs to include the design of an internally consistent English language programme that can be implemented in practice.

The inclusion in the programme of a national curriculum aligned to international standards creates the need for teachers to be trained to teach it. The different bodies that train teachers have to be brought together to ensure that teachers are trained to teach the right things in the classroom. In order to make the teaching of the curriculum effective, students need access to appropriate learning materials, and assessment procedures need to test the right things and measure the extent to which students are achieving the intended learning outcomes. All parties involved must be working together towards common goals.

Integrating the system

The need to integrate the English language education system can perhaps best be highlighted by drawing attention to problems that arise when integration is lacking. The examples cited briely here are discussed at greater length in the relevant chapters of Section B. If speaking proiciency is set as a top priority for the English language programme but the assessment is limited to the testing of reading and writing, then the assessment is not integrated with the rest of the programme.

If the learning materials used do not match the curriculum, or if they do not enable students to achieve the learning goals associated with the curriculum, then there is a lack integration within the programme itself. If students are expected to learn to communicate in English, but teachers are not trained to enable students to develop communicative competence, then there is a lack of integration in the English language education system as a whole. Problems of this kind manifest themselves at the same time, and give students a flawed learning experience which may make it difficult for them to learn at all, or at least to maintain morale.

Progress

expected to use grammatical forms in writing before recognising them in reading, then there is a lack of integration that can only hamper their progress.

It is essential that as students progress through the learning programme the things they are given to learn are appropriate for their present stage of development – in accordance with the principle of developmentally appropriate practice – and presented in the right order, so that the programme is integrated when viewed through time.

Progression

A consequence of the division of the programme into largely independent modules is that particular attention needs to be paid to the management of student transfer from preschool to primary school, and then on to secondary school and perhaps tertiary education. Students entering primary school will have very different experiences of learning English at preschool level, ranging from nothing at all to a good start in speaking and reading; and similarly secondary schools take in students from primary school with a range of ability in English.

Since children spend different lengths of time in preschool, the handover between preschool and primary school can be expected to be problematical. A problem which is discussed elsewhere in this document concerns the teaching of beginning literacy. Among the problems children face are recognising English words, and

understanding English grammar. In both cases, it appears that children are expected to learn the same content at least twice in the course of their education.

For example, according to the national curriculum, much of Year 1 is concerned with letter recognition, and phonics teaching proper begins in Year 2 and continues until Form 5. Children who have already learnt the letters of the alphabet in preschool will not have much to learn in Year 1, and primary school children who have learnt to use phonics methods to recognise words will be doing it all again in secondary school.

Perhaps the most dificult handover problem involves the transition from school to university. The transition is particularly problematical in view of the different routes to university entrance and the different kinds and amounts of tuition available, if any, to prepare students for the English language demands of their university courses.

The ability range

A modern integrated education system is expected to cater for all children across the ability range. Although aspirational targets express the hope that all students will achieve a certain level of proficiency in English at the end of each stage of their education, the reality is that some students will not achieve this level, while others will advance far beyond it.

The different needs of above average students, average students and the weaker students need to be taken into account. Intervention programmes will in some cases be required to provide the above average students with a real challenge, and to prevent the weaker students from being left behind.

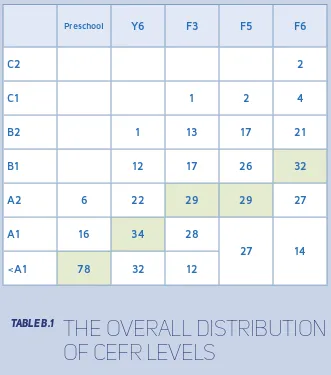

The figures provided in the Cambridge Baseline give cause for concern in connection with the extremes between Year 6 and Form 3. The CEFR measures language proficiency on a scale beginning with A1, and progressing through A2, B1, B2, and C1 to C2. The percentage of students below CEFR A1 falls from 32 in Year 6 to 12 in Form 3, while at the upper end, the percentage above A2 rises from 13 to 31. The percentage in A1 or A2 remains virtually unchanged, from 56 in Year 6 to 57 in Form 3. There is a small amount of improvement, for the figure for A1 falls from 34% to 28%, while the figure for A2 rises from 22% to 29%. If we now compare the figures for Form 3 and Form 5, we find that the largest single group is the 29% in A2 in both cases.

The number below A2 falls from 30% in Form 3 to 27% in Form 5, while the number of those above A2 rises from 31% to 35%. Although these figures do indicate some progress, this progress is slow, especially in the middle of the range; and even in the extremes, the progress slows down between Form 3 and Form 5.

There are many possible explanations for these figures, but one possibility that needs investigation concerns the transfer from primary school to secondary school. How is it that weak students make more progress than average students? What is the favourable circumstance that enables the more able students to flourish in the first years of secondary school?

1.3.3 Quality in the programme

Quality in the programme begins with a quality curriculum, which is then followed through by quality in teaching and learning, in learning materials, and in assessment. The focus here is on these last three components.

Teaching and learning

Classroom teaching and learning is an area which will require a thorough reform in order to be made compatible with the philosophy of teaching and learning which is built into the CEFR and described in the baseline study (pp. 9-14). The problem is

raised in the Executive Summary of the Cambridge Baseline on page 12, where in the upper picture the children are sitting in rows listening to the teacher talking, although one child is more interested in the photographer, while in the lower picture, children are actively involved in learning.

The approach to teaching must be based on what is known about how children learn in general, and how they learn languages in particular. Special attention has to be paid to early learning, because this is when the foundations are laid for lifelong learning. Shaky foundations in English will make it difficult for the child ever to develop a high level of competence in English later on; while on the other hand firm foundations provide the child with the means to achieve excellence. Although the framework does not lay down either how languages should be taught, or how communicative proficiency should be assessed, “there is no doubt that task-based teaching and learning are strongly reinforced” (Little, 2006, p. 169).

The adoption of a communicative approach to the learning of English does not mean that acquiring the forms of English – including pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary – is unimportant. This is because communication skills are based on the knowledge and understanding of the forms of a language, and so learners need to know the forms of the language in order to develop these skills. The forms of the language must be taught not for their own sake, but in order to enable the learner to communicate. This requires of the teacher a much deeper understanding of linguistic form than for the mere teaching of such things as plurals, tense forms and irregular verbs.

The baseline study draws attention (p. 5) to the wide range of achievement at different stages of school education. For example, Form 3 is described as at level A2 on average. In fact this accounts only for about 28% of students, for about 41% of students are below this level, and about 31% above it. In order to be effective, teaching will have to include “differentiation strategies” (p. 13) providing support for the weaker students and suitable activities for the more advanced students.

If our goal is to develop in learners the ability to communicate in English, then our approach to learning must be guided by certain principles including the following:

• Language learning should as far as possible emulate authentic

classroom use;

• The goal of language learning is using the language rather than

knowing about it;

• Language learning is not additively sequential but recursive

and paced differently at different stages of acquisition;

• Language learning is not the accumulation of perfectly

mastered elements of grammar and vocabulary, and learner errors are to be expected;

• Language proiciency involves both comprehension and production

which come together in interaction, although comprehension abilities tend to precede and exceed productive abilities;

• Language use requires an understanding of the cultural context

in which communication takes place;

• The ability to perform is facilitated when learners are actively

engaged in meaningful, authentic, and purposeful learning tasks;

the materials are trying to help children to learn, and the children must be learning something useful and relevant. In the teaching of a language, there must be no gaps or lacunae.

On the other hand, the materials must be free of learner errors. It is important to bear in mind that children will acquire poor models of a language just as effectively as good models. Children who do not have independent access to English outside school are particularly vulnerable if they are given an inappropriate model of English to learn. It is essential to set up a strict and effective system of quality control for English language learning materials.

Assessment

Assessment has to reflect the values of the language programme as a whole. What is taught in the classroom is determined by the curriculum and ultimately by national needs. The purpose of the assessment is to ascertain to what extent students have been successful in achieving the goals set by the curriculum. Current practice needs to be considered in the light of the comments in the baseline study (p. 15). If our goal is communicative competence in English, then this needs to be reflected in the forms of assessment adopted.

The person in the best position to assess students is the classroom teacher. As students develop new skills, their progress can be recorded by the teacher. If the progress is genuine, and

• Educational technologies and textbook materials play support

roles for language learning, and should not determine the curriculum (British Columbia Ministry of Education, 2011, p. 1).

It is already too late at the time of writing to do much about teaching and learning for Wave 1, and these issues will have to be addressed in Waves 2 and 3 and reflected in teacher education. What can be done in the shorter term is to reconsider the curriculum and its influence on classroom practices.

For example, Speaking has emerged in the baseline study as an area of weakness (p. 6 and p. 9), and yet students are required to learn to pronounce English words correctly and speak English with appropriate stress, rhythm and intonation. The question is how they can do this either (a) from a printed textbook or (b) from teachers who cannot do these things for themselves. In this case, classroom practices have important consequences for learning materials.

Learning materials

Learning materials reflect the learning culture for which they are designed. If we change our classroom culture, we shall also need learning materials of a new and different kind. The baseline study (p. 16) outlines the strengths and weaknesses of a sample of primary and secondary materials (see Chapters 5 and 6).

the assessment properly carried out, students should be able to demonstrate their skills in a ‘snapshot’ type of test. The problem with this, as pointed out in the baseline study (p. 13), is that teachers are already “overwhelmed by administration”.

1.3.4 Targets

The national agenda sets as the overall target for our English language programme the production of school leavers and graduates with the level of English proficiency they need to make themselves employable in the modern globalised world. It is not enough to hope that students will reach the required level by the end of their education: a quality system needs to set interim targets for each successive stage. Here for example are some common-sense interim targets:

• Preschool: raised awareness of English, the ability to say simple

things in English and the first steps to English literacy;

• Primary: basic functional English literacy and some limited

ability to communicate in English in familiar social situations;

• Secondary: the ability to use English as a matter of course in

everyday situations with the potential to use English at the place of work;

A1

A2

B1/B2

B2

B2/C1

C1

Preschool

Primary school

Secondary school

Post-secondary

University

Teacher Education

Figure 1.7

CEFR TARGETS FOR

• Post-secondary: sufficient command of English to meet the

challenge of English at university;

• Graduate: the skilled use of English in the context of

employment for those joining the workforce on graduation, and in an academic context for those studying for a higher degree at home or abroad;

• Teacher education: a high level of English proficiency

(combined with pedagogical expertise) leading to effective English teaching in the classroom.

These common-sense targets are presented here for purposes of illustration, and the more carefully considered targets on the CEFR scale are presented above.

A major advantage of using the CEFR is that common-sense targets have already been considered in great detail and linked to a standard scale. The CEFR scale enables us to convert our common-sense targets into formally defined targets which are understood internationally for each stage of our English language

programme (see the CEFR Global Scale in Chapter 3). The

targets set to be achieved by 2025 for our children to reach as they progress through our English language programme are shown in Figure 1.7.

Obviously not all students will reach the target set at each stage; but on condition that the programme is reformed in accordance with the principle of equity, we can reasonably expect that between now and 2025, an increasingly large proportion of our students from all social backgrounds will be achieving the CEFR target set for each stage of education.

1.3.5 Research

A danger that inevitably accompanies highly standardised or integrated education systems is that they are difficult to change. The last thing we want is a juggernaut that creates its own momentum and careers out of control and proves impossible to stop, or steers to a different course. This is how new ideas are stifled and the opportunity to make useful innovations is lost. We therefore need to build flexibility into our English language programme.

The way to do this in an educational context is to take account of relevant research undertaken elsewhere, and to promote research of our own. We need a research culture to ensure that relevant new knowledge, wherever it is created anywhere in the world, is made available here in Malaysia, and used effectively to keep our programme up among the international leaders.

to build up an English language research tradition of our own, and become creators of international knowledge. Research at this level is properly the responsibility of our research universities.

Educational research can be carried out at different levels, and much useful work can be done by people who do not think of themselves as researchers at all. For example, no matter how carefully a new programme is devised, we have to expect problems arising from imperfect integration and uncoordinated implementation. We need a mechanism in place to ensure that any such problems are systematically reported and solved.

Any teacher can report problems, and they can be solved by experienced teachers with the necessary expertise. Innovations should not be introduced in the belief that they might work, and they need to be tested. After initial testing, they need to be beta tested using an appropriate sample of teachers and students. The creation of a research-led English language programme is essential if the government is to achieve its ambition to make Malaysia an educational hub for the region and perhaps beyond.

1.4 Teacher education

While current levels of teacher English proficiency may be sufficient for internal communication within Malaysia, they are very far from sufficient if students are to learn spoken English from their

teachers and go on to speak English effectively in work situations requiring English, or in international situations. Teachers are not ordinary language learners, because they need to be aware of what they are learning in order to teach their students effectively.

1.4.1 Creating a high-performing English education system

It has become internationally known in recent years that in order to create a high-performing education system, it is first necessary to produce a high-calibre teaching workforce. This subsection outlines the challenge we face in the provision of education for English teachers. A report published by McKinsey & Company in September 20076 presents the findings of research into how countries create high-performing education systems. It was found that there were three major success factors that matter most:

1. Getting the right people to become teachers;

2. Developing them into effective instructors;

3. Ensuring that the system is able to deliver the best possible instruction for every child.

Getting the right people begins with effective mechanisms for

selecting teachers for training. Trainees are ideally recruited from