JURNAL

DEMOKRASI

& HAM

INGGRID GALUH MUSTIKAWATI

Perjalanan Penegakan HAM di ASEAN dan Peran Indonesia Dalam

Mendukung Keberlanjutan AICHR MUTIARA PERTIWI

Understanding the Current ASEAN: the Competing Articulations of Order Behind the ASEAN Charter TATAT SUKARSA

Kelembagaan ASEAN dan Isu Lingkungan di Asia Tenggara JUSMALIANI

Komunitas ASEAN Dalam Masyarakat Dunia: Agenda Kerja Indonesia DEAN YULINDRA AFFANDI

Kesiapan Usaha kecil menengah di Indonesia Dalam Menghadapi ACFTA Dan Pasar Tunggal ASEAN 2015 BAWONO KUMORO

Terbit Sejak 20 Mei 2000 ISSN: 1411-4631

Penanggungjawab: Rahimah Abdulrahim, MA

Mitra Bestari:

Dr. Indria Samego, Prof. Dewi Fortuna Anwar, Umar Juoro, MA, MAPE, Rudi M. Rizki, SH., LLM, Andi Makmur Makka, MA

Editor Pelaksana: Zamroni Salim, Ph.D

Editor:

Sumarno, Wenny Pahlemy, Bawono Kumoro,

Inggrid Galuh Mustikawati, Dean Y. Afandi

Sekretaris: Tatat Sukarsa

Produksi: Kosasih

Usaha dan Sirkulasi:

Natassa Irena Agam, Vita Handayani

Desain Grafis:

Aryati Dewi Hadin

Penerbit:

The Habibie Center

Alamat Redaksi:

Jl. Kemang Selatan no.98, Jakarta 12560, Indonesia Telp: 021 7817211 Fax.021 7817212

DAFTAR ISI

Inggrid Galuh Mustikawati

Perjalanan Penegakan HAM Di ASEAN dan Peran Indonesia Dalam Mendukung Keberlanjutan AICHR

Mutiara Pertiwi

Understanding The Current ASEAN: The Competing Articulations of Order Behind The ASEAN Charter

Tatat Sukarsa

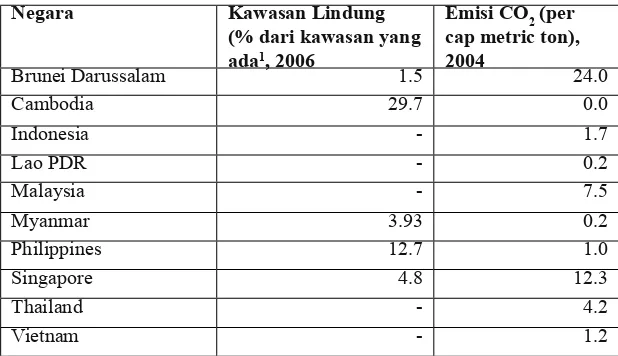

Kelembagaan ASEAN Dan Isu Lingkungan di Asia Tenggara

Jusmaliani

Komunitas ASEAN Dalam Masyarakat Dunia: Agenda Kerja Indonesia

Dean Y. Affandi

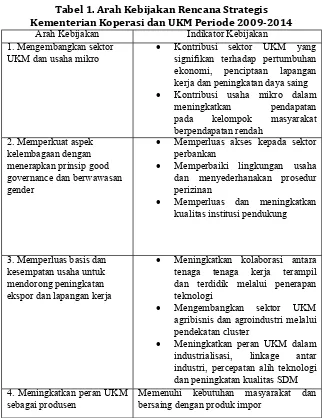

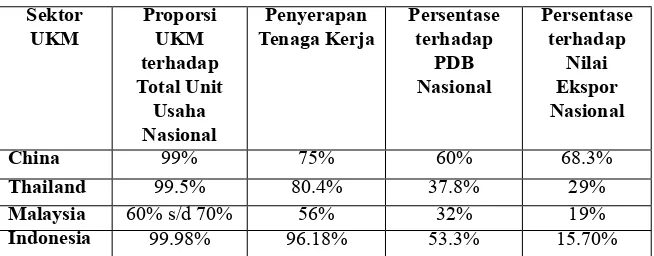

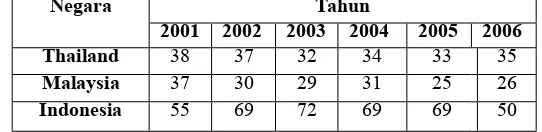

Kesiapan Usaha Kecil Menengah di Indonesia Dalam Menghadapi ACFTA dan Pasar Tunggal ASEAN 2015

Bawono Kumoro

Resensi Buku: ASEAN di Tengah Dinamika Regional dan Global

11

35

59

83

105

PENGANTAR REDAKSI

Jurnal Demokrasi dan HAM Vol. 9 No. 1, 2011

“Peranan Indonesia Dalam Kepemimpinan ASEAN 2011”

Sejak tahun 2007, negara-negara di kawasan Asia Tenggara telah menegaskan komitmennya untuk memperkuat demokrasi, good governance, dan perlindungan hak asasi manusia (HAM). Tekad itu dinyatakan dalam The ASEAN Charter yang ditandatangani para pemimpin ASEAN di Singapura tahun 2007.

ASEAN mempunyai peranan yang strategis untuk meningkatkan kesejahteraan dan perlindungan ekonomi, sosial, hukum dan lainnya bagi masyarakat ASEAN melalui kehidupan yang demokratis dan menghargai hak asasi manusia dalam berbagai bentuknya. Peranan yang strategis itu haruslah diusahakan secara bersama diantara negara ASEAN sehingga bisa memberikan manfaat nyata bagi masyarakat ASEAN.

dinyatakan dalam The ASEAN Charter?

Sebagai pemimpin ASEAN, Indonesia mempunyai tugas dan tanggung jawab dalam mensukseskan agenda-agenda ASEAN diantaranya KTT ASEAN, ASEAN+1, ASEAN+3 dan persiapan East Asian Summit. Dari sisi substansi, berbagai permasalahan yang menumpuk di ASEAN juga harus bisa diselesaikan dengan baik. Indonesia mempunyai peranan yang strategis untuk mengarahkan dan menggerakkan ASEAN: ke arah mana dan bagaimana permasalahan-permasalahan yang ada akan bisa diselesaikan dengan baik baik secara bilateral maupun multulateral.

Dalam Edisi Vol 9 No. 1 tahun 2011, Jurnal Demokrasi dan Ham memuat beberapa tulisan yang terkait dengan ASEAN dan peran serta Indonesia sebagai Ketua ASEAN 2011. Tulisan pertama membahas perjalanan penegakan HAM di ASEAN dengan memberikan penekanan pada pembentukan ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR). Tulisan kedua mengkaji masalah proses pembentukan ASEAN Charter dan permasalahan yang terkait dengan perbedaan konsep dan konsep yang dominan dalam pembuatan ASEAN Charter.

Tulisan ketiga membahas masalah kerusakan lingkungan yang

Hormat Kami,

PERJALANAN PENEGAKAN HAM DI ASEAN DAN

PERAN INDONESIA DALAM MENDUKUNG KEBERLANJUTAN AICHR

Inggrid Galuh Mustikawati

Researcher at the Habibie Center

Email: inggridgm@gmail.com

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to give an overview of human rights enforcement in the region of Southeast Asia. The establishment of ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR) as the starting point of human rights concern in Southeast Asia has led a contradictive point of view. For those who see the form of AICHR as a

significant progress has argued that AICHR was a new breakthrough in

Southeast Asia to answer critics from international community over the human rights enforcement. Yet, pessimistic view also emerged due to its skepticism over AICHR’s focus of work, namely promoting human rights only, it can not work beyond that. Furthermore, the role of Indonesia to support the work of AICHR still continues because Indonesia has a

confidence in term of voicing human rights and democracy issues. At

the conclusion, this paper explains several challenges in human rights enforcement in ASEAN countries.

Pendahuluan I.

Menginjak 62 tahun peringatan Deklarasi Universal Hak Asasi Manusia (HAM), saat ini penegakan HAM mendapatkan dukungan kuat dari sistem konstitusi dan hukum di sebagian besar negara-negara di dunia seiring dengan meluasnya pemahaman dan penerapan nilai-nilai demokrasi. Secara berkala, permasalahan penegakan HAM juga menjadi perhatian khusus baik itu dari kalangan akademisi, media massa, praktisi hukum dan lembaga swadaya masyarakat (LSM) mengingat kasus-kasus kekerasan dan pelanggaran HAM semakin meluas dan terbuka. Sebagaimana disebutkan dalam Deklarasi Universal HAM, bahwa deklarasi tersebut dimaksudkan sebagai suatu standar umum untuk keberhasilan bagi semua bangsa dan semua negara, dengan tujuan agar setiap orang dan setiap badan di dalam masyarakat akan berusaha mengajarkan dan memberikan pendidikan penghargaan terhadap hak-hak dan kebebasan-kebebasan, dan dengan jalan tindakan-tindakan yang progresif yang bersifat nasional maupun internasional, menjamin pengakuan dan penghormatannya yang universal dan efektif, baik oleh bangsa-bangsa dari negara-negara anggota sendiri maupun oleh bangsa-bangsa dari wilayah-wilayah yang ada di bawah kekuasaan hukum mereka (Mukadimah Deklarasi Universal Hak-Hak Asasi Manusia, 1948). Dengan demikian, adanya Deklarasi HAM ini dapat dijadikan sebagai acuan ataupun pedoman bagi setiap orang maupun setiap negara dalam bertindak mengedepankan pentingnya aspek penegakan HAM.

Meskipun proliferasi instrumen HAM internasional berkembang begitu pesat sejak dideklarasikan pada 10 Desember 1948, tapi komitmen atas pengimplementasian Deklarasi Universal HAM mengalami krisis ketika berbagai kasus pelanggaran HAM muncul secara konsisten dan hampir terjadi setiap hari baik dilakukan oleh kelompok tertentu maupun oleh pemegang kekuasaan. Pada dasarnya Deklarasi Universal HAM adalah instrumen non-binding

(Kontras, 2008). Tidak hanya proses ratifikasi yang harus dilakukan oleh setiap negara anggota, namun adalah sebuah kewajiban untuk mengimplementasikan instrumen-instrumen tersebut ke dalam kebijakan legislasi, yudisial dan administrasi.

Dalam konteks kawasan Asia Tenggara, penegakan HAM menjadi perhatian khusus terutama bagi negara-negara yang tergabung dalam Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Peningkatan eskalasi kekerasan yang terjadi di negara-negara anggota ASEAN beberapa tahun terakhir mendorong pembentukan Komisi HAM ASEAN. Hal ini juga sejalan dengan komitmen negara-negara ASEAN untuk menjadikan penegakan HAM sebagai norma dan nilai bersama

(common values) sebagaimana tercantum dalam Piagam ASEAN.

Di samping itu, pembentukan Komisi HAM ASEAN secara tidak langsung juga bisa menjadi sebuah solusi efektif terhadap sejumlah permasalahan HAM yang dihadapi negara-negara anggota ASEAN khususnya terkait dengan permasalahan melemahnya peran dan citra ASEAN sebagai akibat dari ketidakmampuan lembaga regional tersebut dalam menangani kasus-kasus pelanggaran HAM (Dirgantara, 2010). Meskipun banyak pihak yang meragukan komitmen ASEAN dalam mewujudkan Komisi HAM ASEAN, namun langkah ini dinilai sebagai sebuah permulaan signifikan dalam rangka menegakkan HAM.

Tulisan ini bermaksud untuk memberikan deskripsi mengenai perjalanan penegakan HAM di kawasan Asia Tenggara, khususnya pada negara anggota ASEAN dengan memberikan penekanan pada pembentukan ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on

Human Rights (AICHR) dan perjalanannya dalam menunjukkan

Penegakan HAM di ASEAN II.

Dengan komposisi mayoritas negara sedang berkembang, ASEAN didirikan pada tanggal 8 Agustus 1967. Pada awalnya, pembentukan ASEAN ditujukan sebagai respon terhadap Perang Dingin dan ancaman komunisme di kawasan Asia Tenggara. Seiring dengan perkembangan kepentingan dan desakan masyarakat internasional, isu penegakan HAM menjadi isu penting dan integral di ASEAN. Pergeseran kepentingan ASEAN ini disebabkan oleh diakuinya ASEAN sebagai aktor yang signifikan di kancah internasional. Pergeseran orientasi paradigma ASEAN dari pendekatan yang berpusat pada negara ke arah pendekatan yang berorientasi pada masyarakat menjadi karakter baru dari ASEAN seiring dengan bergabungnya Brunei Darussalam (1984), Vietnam (1995), Laos dan Myanmar (1997), dan Kamboja (1999).

Sepanjang kiprahnya dalam penegakan HAM, setiap negara-negara anggota ASEAN memiliki sikap berbeda dalam menangani segala persoalan terkait penegakan HAM di masing-masing negara. Hal ini terkait dengan sistem pemerintahan yang berbeda-beda yang secara tidak langsung mempengaruhi interpretasi masing-masing negara mengenai masalah HAM. Dengan demikian kebebasan berekspresi dan berpendapat disikapi berbeda-beda oleh masing-masing negara anggota ASEAN. Belum lagi dengan masih melekatnya prinsip nonintervensi dan konsensus dalam proses pengambilan keputusan sehingga ruang gerak untuk menegakkan HAM di kawasan Asia Tenggara menjadi terbatas.

mengenai HAM di Kuala Lumpur pada Agustus 1993, keikutsertaan seluruh negara anggota ASEAN dalam Konferensi Dunia mengenai HAM di Wina 1993, dan pembentukan suatu mekanisme HAM regional adalah contoh dari serangkaian komitmen yang dimiliki oleh negara anggota ASEAN untuk memajukan isu penegakan HAM (Dirgantara, 2010).

Terkait dengan gagasan pembentukan mekanisme HAM regional,

Working Group for an ASEAN Human Rights Mechanism merupakan sebuah kelompok pemerhati HAM di kawasan Asia Tenggara, mendukung dan memberikan komitmen yang tinggi untuk mengembangkan gagasan tersebut. Hal ini juga tidak terlepas dari dukungan kerjasama dengan lembaga pemerintah dan LSM di bidang HAM. Dalam ASEAN Ministerial Meeting (AMM) ke-31 di Manila tahun 1998, kelompok kerja informal nonpemerintah berkumpul untuk mekanisme HAM ASEAN. Dengan keberadaan mekanisme ini diharapkan persepsi negara-negara ASEAN mengenai HAM beserta upaya-upaya penegakan HAM dapat lebih dipahami oleh pihak luar dan kerjasama ASEAN di bidang penegakan dan perlindungan HAM dapat ditingkatkan (Joint Communique The 31st ASEAN Ministerial Meeting, 1998).

Sejumlah kasus pelanggaran HAM baik itu pada tingkat internal maupun antar negara-negara ASEAN menjadi tantangan riil untuk dapat ditangani oleh lembaga regional tersebut. Konflik yang terjadi di sebagian besar negara-negara anggota ASEAN telah menyisakan catatan penting terhadap pelanggaran HAM dan seringkali mendapat kecaman dari komunitas internasional. Berikut gambaran sejumlah konflik dan pelanggaran HAM yang terjadi di kawasan Asia Tenggara:

Konflik internal yang berkepanjangan di Myanmar

(1)

menyebabkan puluhan ribu penduduk etnis Karen mengungsi ke perbatasan Myanmar-Thailand (Republika, 2010). Dengan tujuan untuk menggalang dukungan politik, pemerintah Mynmar menginginkan belasan kelompok etnis untuk bergabung dalam proses politik. Namun terjadi penolakan yang dilakukan oleh sebagian besar kelompok etnis tersebut karena tidak adanya lagi kepercayaan terhadap pemerintah yang berkuasa. Akibatnya pemerintah Myanmar melakukan tindakan pengabaian aspek kemanusiaan terhadap penduduk sipil. Salah satu LSM pemerhati masalah HAM, Human

Rights Watch (HRW) menekan pimpinan ASEAN

untuk mendukung terbentuknya sebuah komisi internasional untuk melakukan penyelidikan terhadap pelanggaran hukum dan HAM di Myanmar namun sayangnya dari 16 negara yang mendukung pembentukan komisi internasional tersebut tidak ada satupun dari negara-negara di Asia (HRW, 2011).

Permasalahan konflik perbatasan antara Thailand

(2)

dan Kamboja yang dipicu oleh klaim masing-masing pihak akan kepemilikan kuil Preah Vihear

setelah United Nation Educational, Scientific, and

Culture Organization (UNESCO) menetapkannya

sebagai warisan dunia,

Kekerasan dan intimidasi yang pasang surut

(3)

propinsi tersebut merupakan minoritas muslim di tengah masyarakat mayoritas thailand yang memeluk Budha. Sebenarnya konflik separatisme ini terjadi disebabkan oleh perlakuan tidak adil pemerintah pusat Thailand terhadap eksistensi kelompok muslim di Thailand Selatan.

Kasus genosida berupa kejahatan kemanusiaan

(4)

pada era Pol Pot di Kamboja dengan berlarutnya proses peradilan dan sejumlah permasalahan pelanggaran HAM lainnya.

Konflik antar-etnis juga kerap terjadi sebagai

(5)

bentuk diskriminasi rasial dan adanya pemberlakuan internal security act di Malaysia, Konflik internal yang berkepanjangan juga

(6)

terjadi di Filipina yang melibatkan konflik antara pemerintah pusat dengan bangsa Moro-Mindanao yang menuntut untuk merdeka, memisahkan diri dari pemerintahan Filipina, dan hingga saat ini proses perdamaian di Moro-Mindanao masih berlarut-larut, belum menemukan kata sepakat, Konflik horizontal dan vertikal di Indonesia

(7)

itu, konflik komunal antarsuku di wilayah ini sangat sering terjadi. Persoalan identitas (etnis, agama dan kebangsaan) dan perebutan sumber daya alam sangat kompleks mewarnai konflik-konflik di daerah ini. Kasus yang turut menjadi keprihatinan atas pelanggaran HAM di Indonesia adalah penyerangan terhadap kelompok agama tertentu dengan menghalalkan kekerasan atas nama agama. Lebih lanjut, kasus pelanggaran HAM yang baru-baru ini terjadi terkait persoalan penembakan TNI AD terhadap sejumlah warga yang disebabkan oleh sengketa tanah dan Pusat Latihan Tempur (Puslatpur) di Kabupaten Kebumen (Republika, 2011). Serangkaian kekerasan ini membuat negara ini terlihat sebagai bangsa tak bertuan, di mana pembiaran terhadap kekerasan terjadi.

Dalam upaya penegakan HAM, peran ASEAN sangat diharapkan untuk dapat mengambil langkah memperjuangkan aspirasi masyarakat ASEAN secara adil. Dengan demikian, kemampuan diplomasi masing-masing negara ASEAN menjadi instrumen penting untuk melaksanakan penegakan HAM. Diplomasi suatu negara bersumber pada kepentingan nasional dari negara tersebut yang bertujuan untuk menjaga komitmen negara anggota ASEAN akan pentingnya penegakan HAM sebagaimana tercantum dalam

Piagam ASEAN yang telah diratifikasi pada akhir tahun 2008.

“Menghormati kebebasan fundamental, pemajuan dan perlindungan hak asasi manusia, dan pemajuan keadilan sosial,”

Prinsip ini mengisyaratkan bahwa ASEAN harus berperan nyata dalam menjaga kesinambungan kawasan ASEAN dalam menegakkan HAM. Untuk mendukung upaya itu, Pasal 14 Piagam ASEAN menegaskan mengenai Komisi HAM ASEAN:

“Selaras dengan tujuan-tujuan dan prinsip-prinsip Piagam 1.

ASEAN terkait dengan pemajuan dan perlindungan hak-hak asasi dan kebebasan fundamental, ASEAN wajib membentuk badan hak asasi manusia ASEAN.

Badan Hak Asasi Manusia ASEAN ini bertugas sesuai 2.

dengan kerangka acuan yang akan ditentukan oleh Pertemuan para Menteri Luar Negeri ASEAN.”

SelainPiagam ASEAN, negara anggota ASEAN juga memiliki Perjanjian Persahabatan dan Kerjasama di Asia Tenggara (Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia) yang ditandatangani di Bali tahun 1976. Melalui perjanjian ini, negara-negara anggota ASEAN menyepakati

code of conduct atau aturan perilaku dalam pelaksanaan hubungan kerjasama antar negara anggota ASEAN yang mengesampingkan kekerasan dan mengedepankan cara-cara damai dan penghormatan terhadap HAM dalam penyelesaian konflik di antara negara anggota ASEAN.

Signifikansi Keberadaan AICHR di Kawasan Asia III.

Tenggara

maka korban pelanggaran HAM diberi ruang untuk memperjuangkan penyelesaian kasusnya di tingkat regional. Hal ini menciptakan kondisi adanya kemungkinan para pelaku pelanggaran HAM yang lolos dari jerat hukum di negara mereka tidak bisa lolos di tingkat regional dengan adanya Komisi HAM ASEAN tersebut (Sasmini, 2009).

Pada hakikatnya, pembentukan Komisi HAM ASEAN merupakan langkah yang signifikan terhadap penguatan nilai-nilai HAM untuk diterapkan di kawasan ASEAN. Lebih lanjut, pembentukan Komisi HAM juga membuka peluang yang lebih besar akan perbaikan implementasi dan penegakan HAM di ASEAN. Untuk itu, pada bulan Oktober 2009 ASEAN Intergovernmental

Commission on Human Rights (AICHR) dibentuk berdasarkan

Pasal 14 Piagam ASEAN. Mengacu pada Term of Reference (ToR) AICHR, tujuan dari pembentukan Komisi HAM ASEAN ini adalah:

Untuk mempromosikan dan melindungi hak

(1)

asasi manusia dan kebebasan-kebebasan dasar dari warga anggota ASEAN,

Untuk menjaga hak bangsa-bangsa ASEAN agar

(2)

dapat hidup dalam damai, bermartabat dan sejahtera,

Untuk mewujudkan tujuan organisasi ASEAN

(3)

sebagaimana tertuang dalam Piagam yakni menjaga stabilitas dan harmoni di kawasan regional, sekaligus menjaga persahabatan dan kerja sama antara anggota ASEAN,

Untuk mempromosikan HAM dalam konteks

(4)

regional dengan tetap mempertimbangkan karakteristik, perbedaan sejarah, budaya, dan agama masing-masing negara, serta menjaga keseimbangan hak dan kewajiban,

Untuk meningkatkan kerja sama regional melalui

(5)

melindungi HAM, dan

Untuk menjunjung prinsip-prinsip HAM

(6)

internasional yang tertuang dalam Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Vienna Declaration

serta program pelaksanaannya, dan instrumen HAM lainnya, dimana anggota ASEAN menjadi pihak.

Mengacu pada poin keempat ToR AICHR, Komisi HAM ASEAN ini memiliki berbagai macam fungsi dalam menegakan HAM di ASEAN, diantaranya merumuskan upaya pemajuan dan perlindungan HAM di kawasan ASEAN melalui edukasi, pemantauan, diseminasi nilai-nilai dan standar HAM internasional, mendorong negara anggota ASEAN untuk menerima dan meratifikasi instrumen HAM internasional, mendukung implementasi secara utuh atas instrumen ASEAN terkait penegakan HAM, menyediakan pelayanan konsultasi, dialog dan bantuan teknis atas setiap permasalahan HAM di ASEAN dengan melibatkan LSM dan stakeholders lain serta melakukan penelitian atas penegakan HAM di ASEAN.

Peresmian Komisi HAM ASEAN ini dilaksanakan di Hua Hin, Thailand, di sela-sela pelaksanaan Konferensi Tingkat Tinggi (KTT) ASEAN ke-15 yang dihadiri oleh seluruh anggota komisi yang berjumlah 10 orang. Adapun anggota AICHR adalah perwakilan dari masing-masing negara anggota ASEAN yakni Dr. Sriprapha Petcharamesree dari Thailand yang ditetapkan sebagai Ketua AICHR, Om Yentieng (Kamboja), Rafendi Djamin (Indonesia), Bounkeut Sangsomsak (Laos), Awang Abdul Hamid Bakal (Malaysia), Kyaw Tint Swe (Myanmar), Rosario G. Manalo (Filipina), Richard Magnus (Singapura) dan Do Ngoc Son (Viet Nam). Sayangnya, sebagai langkah awal, pembentukan AICHR ini masih bertujuan untuk mempromosikan isu-isu terkait penegakan HAM, belum memasuki ranah perlindungan HAM.

komitmen yang bervariasi dalam menyikapi pembentukan komisi tersebut. Myanmar dapat dikatakan sebagai negara dengan komitmen paling lemah terhadap penegakan dan perlindungan HAM. Sementara itu, Indonesia, Thailand dan Filipina mengakui bahwa masing-masing negara tersebut memiliki komitmen kuat atas penegakan dan perlindungan HAM. Sedangkan Malaysia dan Singapura menunjukkan posisi di tengah-tengah. Meskipun pemenuhan hak sipil warga negara seringkali dibatasi, namun pemenuhan hak ekonomi dan sosial dapat dikatakan lebih baik jika dibandingkan dengan Indonesia dan Filipina (Fitria, 2009).

Pembentukan Komisi HAM ASEAN ini memiliki karakteristik khusus dan berbeda jika dibandingkan dengan komisi HAM di kawasan lain.

Pertama, pembentukan Komisi HAM di kawasan lain didasarkan pada instrumen hukum yang khusus dan kuat seperti Konvensi Amerika atas HAM (The American Convention on Human Rights), sementara pembentukan Komisi HAM ASEAN hanya didasarkan pada salah satu prinsip dari Piagam ASEAN sehingga diperlukan aturan lain yang mengatur mekanisme instrumen hukum yang lebih teknis. Untuk itu, sebagaimana disebutkan dalam Pasal 14 Piagam ASEAN, Menteri Luar Negeri ASEAN diberikan mandat untuk memformulasikan ToR AICHR sebagai kerangka acuan pelaksanaan kegiatan Komisi HAM ASEAN tersebut. Kedua, dengan melihat landasan pembentukannya, AICHR bukanlah badan atau komisi independen karena AICHR dibentuk oleh pemerintah, di mana keanggotaannya merupakan perwakilan dari negara-negara anggota ASEAN sehingga AICHR bergerak mewakili pemerintah.

Sebagaimana tertuang dalam ToR AICHR ayat 5.2 bahwa keanggotaan AICHR merupakan perwakilan dari masing-masing negara ASEAN yang ditunjuk oleh pemerintah. Keberadaan AICHR merupakan langkah signifikan bagi awal kesamaan persepsi dari masing-masing negara anggota ASEAN atas penegakan HAM di kawasan Asia Tenggara.

Selama tahun 2010, AICHR telah melaksanakan sejumlah pertemuan untuk melakukan sosialisasi dan dukungan dari komunitas internasional, seperti kunjungan ke Amerika Serikat atas undangan dari Presiden Barrack Obama, disamping sejumlah pertemuan dengan

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations High

Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), LSM internasional bidang HAM

dan beberapa institusi lainnya (Sukarsa, 2011). Hingga Februari 2011, pertemuan AICHR telah dilakukan sebanyak empat kali dengan serangkaian agenda untuk penguatan penegakan HAM. Dalam pertemuan ini, setiap perwakilan negara anggota ASEAN sepakat untuk menjadikan tahun 2011 sebagai tahun pengimplementasian kerja AICHR untuk mempromosikan dan melindungi HAM di ASEAN, serta mengedepankan kontribusi ASEAN agar lebih berorientasi pada masyarakat. Pertemuan yang dipimpin oleh perwakilan Indonesia, Rafendi Djamin, dinilai cukup strategis mengingat dalam pertemuan tersebut AICHR menetapkan beberapa agenda dan prioritas kegiatan pada tahun 2011 yaitu (1) Penyusunan ASEAN Declaration on Human Rights, (2) Penguatan sekretariat AICHR, dan (3) Mendorong interaksi AICHR dengan masyarakat sipil (Pertemuan keempat AICHR, 2011). Lebih terperinci, dalam pertemuan tersebut telah disepakati dan dibahas beberapa agenda diantaranya disepakatinya Pedoman Operasional AICHR, pembentukan drafting team untuk penyusunan

ASEAN Declaration on Human Rights, mempertimbangkan penyusunan

ToR studi tematik atas Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), HAM dan migrasi, dan agenda tindak lanjut berbagai usulan engagement

AICHR dengan ASEAN partners dan ASEAN sectoral bodies. AICHR juga mempersiapkan workshop dan paper mengenai isu-isu terkait hak perempuan dan anak di kawasan Asia Tenggara (Press Release of

10-13 februari 2011).

Sebagaimana telah disebutkan diatas, landasan dasar pembentukan AICHR tidak terlepas dari acuan Piagam ASEAN dan Perjanjian Persahabatan dan Kerjasama tetapi kedua instrumen tersebut belum pernah sama sekali digunakan untuk menyelesaikan konflik antar negara anggota ASEAN. Bukan karena tidak ada konflik di negara-negara ASEAN, melainkan karena masih rendahnya rasa saling percaya di antara negara anggota. Selama ini, negara-negara ASEAN yang berkonflik lebih memilih penyelesaian secara bilateral atau menyerahkan penyelesaian persoalan kepada lembaga internasional seperti Mahkamah Internasional yang berkedudukan di Den Haag, Belanda (Kompas, 2011).

dalam menyelesaikan konflik antar-negara anggota ASEAN.

Peran Indonesia dalam Mendukung AICHR IV.

Dalam lingkup negara-negara ASEAN, Indonesia termasuk negara yang memiliki kepercayaan tinggi dalam hal menyuarakan masalah HAM dan demokrasi. Bagi Indonesia, Komisi HAM ASEAN dapat menjadi salah satu instrumen penguatan peran diplomasi Indonesia berbasis kekuatan norma (normative power) di kawasan Asia Tenggara (Dirgantara, 2010). Sejak era reformasi, pemerintah Indonesia memang terlihat gencar melakukan ratifikasi instrumen-instrumen HAM karena isu penegakan HAM telah menjadi pilar penting dalam proses kehidupan politik di Indonesia. Lebih lanjut, HAM dan demokrasi tidak dapat dipisahkan dalam proses pembangunan nasional di Indonesia. Dengan demikian, komitmen tinggi Indonesia dalam pemajuan dan perlindungan HAM tercermin dalam berbagai keterlibatan baik di tingkat nasional, regional maupun dalam forum-forum PBB.

Ada beberapa indikasi atas keberhasilan penegakan HAM di Indonesia pasca-Orde Baru, seperti adanya kebebasan pers dan kebebasan berserikat untuk mendirikan partai politik, organisasi massa dan LSM. Selain itu pada Sidang Tahunan Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat (MPR) tahun 2000 terjadi amandemen kedua konstitusi yang turut menyertakan pasal-pasal mengenai HAM dan pembuatan Undang-Undang No. 39/1999 tentang Hak Asasi Manusia.

Sejumlah instrumen HAM pokok telah diratifikasi, diantaranya:

Konvensi Jenewa 12 Agustus 1949 (diratifikasi dengan UU

(1)

No. 59 Tahun 1958),

Konvensi tentang Hak Politik Kaum Perempuan/

(2) Convention

of Political Rights of Women (diratifikasi dengan UU No. 68

tahun 1958),

Konvensi Penghapusan Segala Bentuk Diskriminasi

(3)

Discrimination Against Women (diratifikasi dengan UU No.

7, 1984),

Konvensi Hak Anak/

(4) Convention on the Rights of the Child

(diratifikasi dengan Keppres No. 36, 1990),

Protokol Tambahan Konvensi Hak Anak mengenai

a.

Perdagangan Anak dan prostitusi Anak, dan Pornografi Anak/Optional Protocol to the Convention on the rights of the Child on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution dan Child Pornography (ditandatangani pada tanggal 24 September 2001),

Protokol tambahan Konvensi Hak Anak mengenai

b.

Keterlibatan Anak dalam Konflik Bersenjata/Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child

on the Involvement of the Children ini Armend Conflict (ditandatangani pada 24 September 2001),

Konvensi Pelarangan, Pengembangan, Produksi dan

(5)

Penyimpanan Senjata Biologis dan Beracun serta Pemusnahnya/Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production and Stockpiling of Bacteriological (Biological) and Toxic Weapons and on their Destruction

(diratifikasi dengan Keppres No. 58, 1991),

Konvensi Internasional terhadap Anti Apartheid dalam

(6)

Olahraga/International Convention Againts Apartheid in Sports (diratifikasi dengan UU No. 48 tahun 1993),

Konvensi Penghapusan Penyiksaan dan Perlakuan atau

(7)

Penghukuman lain yang Kejam, tidak Manusiawi, dan Merendahkan Martabat Manusia/Convention Against Torture (diratifikasi dengan UU No. 5, 1998),

Konvensi orgnisasi Buruh Internasional No. 87, 1998

(8)

tentang Kebebasan Berserikat dan Perlindungan Hak untuk Berorganisasi/International Labour Organisation (ILO)

Convention No. 87, 1998 Concerning Freedom Association and Protection on the Rights to Organise (diratifikasi dengan

UU No. 83 tahun 1998),

Konvensi Internasional penghapusan Segala Bentuk

Diskriminasi Rasial/International Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Racial Discrimination (diratifikasi

dengan UU No. 29, 1999),

Konvensi Internasional untuk penghentian Pembiayaan

(10)

terorisme/International Convention for the Supression of the Financing Terrorism (ditandatangani pada 24 September 2001),

Kovenan Internasional Hak-Hak Ekonomi, Sosial, dan

(11)

Budaya/International Covenant on Economy, Social, and Culture Rights (diratifikasi dengan UU No. 11, 2005), dan

Kovenan Internasional Hak-Hak Sipil-Politik/

(12) International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (diratifikasi dengan

UU No. 12, 2005).

Dalam perjalanan proses ratifikasi sejumlah instrumen HAM ini tentunya mengalami banyak hambatan. Proses ratifikasi Konvensi Anti-Penyiksaan (CAT) dilakukan setelah adanya tekanan dari komunitas internasional atas adanya dugaan penyiksaan yang terjadi sekitar proses jajak pendapat Timor Timur tahun 1999. Demikian pula untuk ratifikasi Konvensi Penghapusan Segala Bentuk Diskriminasi Rasial (ICERD) dilakukan setelah dunia internasional mengecam dugaan terjadinya kekerasan rasial pada peristiwa kerusuhan Mei 1998.

pertama. Lalu, bersama-sama dengan Menteri Luar Negeri Thailand dan Menteri Luar Negeri Kamboja, Menteri Luar Negeri Marty Natalegawa berangkat menuju New York, Amerika Serikat, untuk memberikan pertimbangan dan masukan mengenai peran ASEAN dalam menyelesaikan konflik internal. Langkah ini terbukti efektif dengan stabilnya kembali wilayah konflik di perbatasan Thailand dan Kamboja. Meskipun wilayah kawasan konflik seluas 4,6 km2 tersebut masih tegang, tetapi para tentara yang bertugas dapat menahan diri untuk tidak kembali angkat senjata (Kompas, 2011).

Sikap proaktif yang diambil oleh Indonesia sebenarnya dimaksudkan untuk menghindari adanya kekosongan pada tingkat kawasan sehingga dapat menghindari intervensi secara langsung oleh DK PBB. Meskipun demikian, keterlibatan DK PBB tetap dibutuhkan dalam rangka mendukung upaya Indonesia selaku Ketua ASEAN (Kompas, 2011). ASEAN yang selama ini terkesan sunyi senyap dan seringkali hanya bertindak sebatas mengeluarkan pernyataan setiap kali terjadi konflik antarnegara anggota, kini menunjukkan langkah yang lebih maju dengan mengantisipasi perluasan konflik dan menghindari terjadinya pelanggaran HAM di kawasan Asia Tenggara.

dengan semangat universalitas HAM serta memiliki kekuatan untuk merespon situasi HAM di kawasan Asia Tenggara (Tempointeraktif, 2011).

Tantangan Penegakan HAM di ASEAN V.

Di samping pertumbuhan ekonomi di Asia Tenggara yang menggambarkan variasi pemulihan akibat krisis ekonomi global, persoalan penegakan HAM yang krusial di masing-masing negara anggota ASEAN turut menjadi perhatian masyarakat internasional. Sejalan dengan proses pematangan komisi HAM ASEAN, sejumlah kritik dan kontradiksi pun bermunculan. Namun, paling tidak AICHR memiliki fungsi strategis karena masyarakat ASEAN memiliki perangkat “tambahan” untuk menjamin pemenuhan HAM mereka. Dengan kata lain, keberadaan AICHR hanya sebatas pelengkap (complement), bukan pengganti (substitute) dari mekanisme penegakan HAM nasional di masing-masing negara anggota ASEAN (hukumonline, 2009).

pemantauan nantinya bisa menjadi bagian integral dalam cakupan kerja AICHR.

Dalam pandangan sejumlah LSM pejuang HAM, keberadaan AICHR bisa menjadi otokritik internal terhadap sejumlah persoalan seperti kekerasan, pengekangan hak-hak sipil-politik, impunitas, tidak terpenuhinya hak-hak dasar ekonomi/sosial/budaya, dan masalah migrasi dan buruh migran di kawasan Asia Tenggara. Sebagaimana dikemukakan oleh Kontras bahwa AICHR lebih produktif sebagai mekanisme koreksi internal di kawasan ASEAN bila para pemimpinnya membuka diri terhadap keterlibatan aktif masyarakat sipil, termasuk komunitas korban. Semestinya hal ini bisa berjalan dengan baik mengingat orietasi ASEAN yang telah beralih pada masyarakat (people-oriented). AICHR dipandang sebagai komisi yang masih berkembang, dalam arti bahwa mandat AIHCR diharapkan akan diperluas pada masa mendatang hingga bisa menjadi instrumen bagi korban khususnya untuk mendapatkan perlindungan dan pemenuhan hak-hak mereka (Politik Indonesia, 2010).

Dari 14 fungsi AICHR yang ada, hanya ada tiga fungsi yang bisa dikategorikan sebagai fungsi proteksi. Fungsi pertama adalah

melainkan investigasi pencarian fakta. Tiga fungsi proteksi inilah yang masih diperjuangkan oleh Indonesia namun belum berhasil.

Proses diplomasi yang dijalankan oleh delegasi Indonesia dalam memperjuangkan penegakan HAM di ASEAN masih belum mengubah posisi satu lawan sembilan sehingga jalan kompromi menjadi solusi yang tepat. Kompromi itu melahirkan apa yang disebut sebagai deklarasi politik pendirian AICHR sekaligus merupakan titik tolak dari visi yang akan dijalankan oleh AICHR. Deklarasi ini merupakan sebuah pernyataan politik dari para pemimpin ASEAN. Poin ini menjadi modal yang sangat besar bagi Indonesia untuk terus menuntut agar review pertama yang akan dilakukan pada lima tahun mendatang adalah untuk memperkuat fungsi-fungsi proteksi AICHR yang belum mempunyai kekuatan untuk membahas situasi HAM negara-negara anggota (Djamin, 2010).

militer maupun sipil negara-negara ASEAN sendiri untuk diterjunkan di daerah konflik. Dengan demikian, sudah saatnya bagi ASEAN untuk tidak meletakkan setiap konflik yang terjadi di bawah karpet dan setiap negara anggota ASEAN dibiarkan mencari jalan keluar sendiri dalam menyelesaikan konflik perbatasan. Sekarang saatnya ASEAN bersikap proaktif dan menunjukkan kredibilitas sebagai organisasi kerjasama regional yang memang dibutuhkan negara-negara anggota menuju terbentuknya Komunitas ASEAN 2015 (Kompas, 2011).

Usaha promosi dan perlindungan HAM yang dilakukan AICHR tidak semata dibebankan pada institusi AICHR sendiri karena penegakan HAM adalah kerja semua pihak. Untuk itu dukungan dari pemerintah, media, akademisi, LSM bidang HAM dan organisasi kemasyarakatan sangat dibutuhkan dalam membangun koordinasi untuk mendukung upaya sosialisasi kerja AICHR. Keberadaan AICHR juga diharapkan dapat mengangkat isu-isu kemanusiaan yang selama ini tidak terwadahi dengan baik khususnya dalam kontek hubungan antar negara-negara ASEAN seperti isu buruh migran, perebutan sumber daya alam di perbatasan dan sebagainya. Menjadikan AICHR sebagai wadah yang kompeten dalam menegakkan HAM bukan hanya sekedar

platform, namun dengan kerja sama semua pihak, penguatan fungsi

kerja AICHR dapat terwujud di kemudian hari.

-oooOooo-Daftar Pustaka

Antara News. 2009. AICHR dan Penguatan Perlindungan HAM di

ASEAN. www.antaranews.com (Diakses pada 3 Mei 2011).

ASEAN Community Indonesia. 2011. Pertemuan Ke-4 ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights. http:// www.aseancommunityindonesia.org (Diakses pada 5 Mei 2011).

Dirgantara, Igor. 2010. Pembentukan ASEAN Intergovernmental on Human Right (AICHR) dan Komitmen Indonesia dalam Penegakan HAM dan Demokrasi di Asia Tenggara. http:// oseafas.wordpress.com (Diakses pada 7 Mei 2011).

Djamin, Rafendi. 2010. Pelanggaran HAM di ASEAN: AICHR

Tidak diperbolehkan melakukan Review. http://www.

tabloiddiplomasi.org (Diakses pada 9 Mei 2011).

Fitria. 2009. Questioning the Prospect of Upholding Human Rights in Southeast Asia in the Coming Five Years. Postscript Vol. VI, No. 5, September-Oktober.

Hukum Online. 2009. Menlu ASEAN Sepakati TOR Pembentukan Komisi HAM Regional. http://www.hukumonline.com (Diakses pada 8 Mei 2011).

Human Rights Watch (HRW). 2005. ASEAN: Reject Burma as Regional Group’s Chair. www.hrw.org (Diakses pada 14 Juni 2011).

Joint Communique The 31st ASEAN Ministerial Meeting (AMM) Manila, Philippines, 24-25 Juli 1998. http://www.aseansec.org/698. htm (Diakses pada 3 Mei 2011).

Kompas. 2011. Penyelesaian Konflik Thailand-Kamboja. http:// nasional.kompas.com (Diakses pada 8 Mei 2011).

Kontras. 2008. Evaluasi Penegakan HAM: Catatan Peringatan 60

Tahun Deklarasi Universal HAM. http://www.kontras.org

(Diakses pada 30 April 2011).

Kontras. 2011. Mukadimah Deklarasi Universal Hak-Hak Asasi

Manusia. www.kontras.org (Diakses pada 2 Mei 2011).

LIPI. 2011. Kerangka Pencegahan konflik di Indonesia, Draft Penelitian.

Politik Indonesia. 2010. AICHR bisa Menjadi Otokritik Internal ASEAN. http://www.politikindonesia.com (Diakses pada 7 Mei 2011).

Press Release of the Fourth ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights. 10-13 Februari 2011. http://www.aseansec. org/25872.htm (Diakses pada 7 Mei 2011)

pada 15 juni 2011).

Republika. 2010. 20 Ribu Warga Mynmar Lari ke Thailand. www. republika.co.id (Diakses pada 15 Juni 2011).

Sasmini. 2009. Menanti Pembentukan Badan HAM ASEAN. http:// sasmini.staf.uns.ac.id/2009 (Diakses pada 30 April 2011).

Sukarsa, Tatat. 2011.Indonesia’s Leadership in ASEAN 2011: Political Perspective and Human Rights. Postscript Vol. VIII No. 1, Januari-February.

Tempointeraktif. 2011. Komisi HAM ASEAN Minta Indonesia Maksimalkan Peran. http://www.tempointeraktif.com (Diakses pada 9 Mei 2011).

Term of Reference AICHR. http://www.aseansec.org/DOC-TOR-AHRB.

pdf (Diakses pada 30 April 2011).

Wahyuningrum, Yuyun. 2009. ASEAN’s Road Map towards Creating a Human Rights Regime in Southeast Asia. Human Rights Milestones: Challenges and Development in Asia, Forum-Asia.

UNDERSTANDING THE CURRENT ASEAN:

THE COMPETING ARTICULATIONS OF ORDER BEHIND THE ASEAN CHARTER

Mutiara Pertiwi1

Lecturer and researcher at UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta Email: mutiapertiwi@gmail.com

Abstract

This study ofers an alternative explanation behind the slow yet decorative progress of ASEAN. It unpacks the competing articulations of order contained in the very foundation of the current ASEAN, the ASEAN Charter. The contestation was mainly over the issues of people oriented purposes and legalistic non-compliance instruments of order. A thin solidarist security order dominated the clauses as proposed by Malaysia, Brunei Darussalam, and Singapore. The compromise between diferent conceptions of order enabled ASEAN to develop potentials to address security challenges in the region. There was an absence of non-compliance mechanisms to provide disincentives for violation of agreements. By this, ASEAN’s capacities to address regional problems were not improved. This suggests that a deeper ASEAN community was still a considerable distance, as was a more just order in Southeast Asia.

Keywords: ASEAN, ASEAN Charter, articulation, conceptions of order

1 This article is based on a chapter of his Master thesis in Australian National

Introduction I.

Facing the second decade of the century, ASEAN is still well-attached to its reputation for being ‘long on talk, short on action (Caballero-Anthony, 2008). This means that ASEAN had many commitments but that these were minimal in manifestation. In this regard, ASEAN’s reliance on persuasive norms was considered to be inadequate. Persuasive norms refer here to norms, which do not incorporate a carrot and stick approach to stimulate compliance. The incentives that they provide for member states to fulfil their commitments in practice are unclear.

This essay is ofering an alternative explanation behind the slow yet decorative progress of ASEAN. It will unpack the competing articulations of order contained in the very foundation of the current ASEAN, the ASEAN Charter. It argues that there were three competing conceptions of order at this historical juncture, which were: a normative-contractual order, a thin solidarist security order, and a solidarist security order. Among them, the thin solidarist security order which was articulated by Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei Draussalam was the most dominant. This impeded eforts to draft the ASEAN charter in a manner which would enhance ASEAN’s capabilities in addressing challenges in the next decade of the 21st century.

To demonstrate this, the discussion is divided into four parts: (1) introducing the analytical framework; (2) elaboration of old and new challenges to Southeast Asia at the beginning of the 21st century; (3) identifying the competing conceptions of order in the drafting of the ASEAN Charter; and (4) analysing then the contribution of the most dominant conception of order in the signing of the ASEAN Charter.

An analytical framework: Understanding ASEAN through II.

In this essay, ‘the principal conceptions of order’ will be revealed through identifying the key ideas of order, which are articulated and desired by actors involved in the evolution of ASEAN. This conceptions of ‘order’ is considered as one of essential dimensions of ASEAN’s image, as recommended in leading literatures on ASEAN, such as in Leifer’s and Acharya’s.2 The principal ideas of order that animate debate in ASEAN evolution may or may not be the most dominant idea of order at the conclusion of each stage of the ASEAN negotiations. However, they are the ones which present powerful visions of order used to support or resist order change.

Hedley Bull, one of the most prominent scholars in the English School, defines order as a purposive ‘pattern of activity that sustains the elementary goals of the society of states’ which are ‘limitations of violence…, the keeping of promises, and the stability of possessions…’ (Bull, 1977). With this definition, Bull contends that order is a product of social construction. It is a result of states’ conscious eforts to reduce unpredictability through social norms and interactions. The main elements of order are ‘goals, pathways, and instruments (Bull, 1977). Goals refers to the articulation of purpose in ASEAN, such as political survival or prosperity; pathways refer to ‘arrangements’ to maintain or establish order, such as the/a balance of power or community building; and instruments refer to the ‘means’ by which order will be enforced, such as norms, war, or diplomacy (Alagappa, 2003). In the empirical parts of this essay, these three elements of order will reveal actors’ conformity to a particular conception of order. This will reveal the extent to which ASEAN order has evolved across time.

Hedley Bull developed a spectrum of order based on the depth

of social interactions between states and between other actors in international society. He identified three major spheres in this spectrum: an international system; an international society; and a world order. Total anarchy is located at one extreme point of this spectrum of order; it is located at the weakest degree of social interactions in ‘international systems’ where interaction among states is driven solely by power considerations. The development of social norms is very weak and security dilemma drives state behavior at this point. This is envisaged as a highly state-centric system. All states only mind their own survival in a zero-sum logic: one’s security is a threat to others’ security. The states keep accumulating power to ensure they have adequate military force to defend their interests. Meanwhile, at the other extreme point of the spectrum of order is ‘world order’ where individuals no longer need states to represent the domestic community at the international level. Here, interstate order is obsolete because individuals can pursue justice and their own ideals without states. The state system is replaced by ‘a great society of all mankind’ (Bull, 1977).

At the middle of the spectrum of order is international society. This is present when states are ‘conscious’ of their ‘common values, interests, and goals (Bull, 1977). States start to develop norms to manage their relations and therefore to sustain order. International society is ‘via media’ between an ‘international system’ and a ‘world order;’ it is an intermediary zone between state centric and human centric order (Bull, 1977). It can also be defined as a sphere of order where ‘the element of state of war and of transnational solidarity’ compete and negotiate in achieving goals (Bull, 1977).

people and territory and, therefore, non-interference norms are the main instrument of order. States are ‘capable of agreement only for certain minimum purposes (Wheeler and Dunne, 1996). The extent to which states would comply with international norms depends on the level of a state’s interest in a given norm. In this essay, pluralist order is also characterised as security order.

On the other hand, the solidarist order’s features of order are closer to a world order; it is a more cosmopolitan vision of order that places the individual, their security, and rights at the centre of order (Bain, 2007). It promotes international law and peaceful instruments of order in maintaining order rather than the use of military force (Wheeler and Dunne, 1996).. In his account of solidarist or moral order, Bull admits that restoring justice is a difficult pathway to order. It might clash with other goals of society such as ‘peace and security.’ This conflict might happen when restoring justice requires international society to radically violate its existing norms, for example, in the case of humanitarian intervention (Bull, 1983). Bull affirms that those promoting moral order should carefully consider its consequences for international society. It means that pursuing justice requires a wise application to avoid causing more harm than good. As Bull argued, progressive politics should always ‘search for a reconciliation between order and justice.3 A just and prosper society will persuade states and people to be more cooperative in international society because they know that the system will promote a fair distribution of rights and obligations. This will create a more cohesive international order.

In this essay, the problem of moral order is identified as occurring in at least two forms. The first refers to the violation of people’s rights and obligations, and the second refers to competing moral claims between peoples. The former form of moral problem commonly exists when the powerful abuse the rights of the powerless such as 3 As quoted and rephrased by Wheeler and Dunne in Nicholas J. Wheeler

in instances of human rights violations. Meanwhile, the problem of competing moral claims of communities commonly results from diverse interpretations of history as in the case of historical territorial disputes. Diferent communities may have diferent ways of viewing history and of judging whether particular outcomes are just. For example, one party in a dispute may refer to colonial map in claiming a territory while the other party to pre-colonial kingdom’s map. Both of them have justifiable claim over the disputed territory based on their history. As history is not only part of states’ order but also people’s source of sense of order, many tensions in territorial disputes occur at people to people level and generated suspicions between neighboring communities.

Muthiah Alagappa argues that the degree of security order is determined by the degree of states’ compliance to norms. The more respectable ‘the rule of law’ for states, the more cohesive the security order will be (Wheeler and Dunne, 1996). Alagappa then develops this assumption into three categorisations of order in international society based on the degree of ‘rule-governed’ interactions. These range from ‘instrumental order’ to ‘normative order’ to ‘solidarist security order’ (Wheeler and Dunne, 1996).

An instrumental order is a category of security order which closely parallels the realists’ power struggle for survival (Wheeler and Dunne, 1996). The main ‘pathways’ to order are balance of power, hegemony, and concert of power. Moral considerations are absent in this order. States mainly pursue their interests through military means while social norms are underdeveloped. Some social institutions exist, but most of them are designed only to promote ‘basic coexistence’ rather than to ‘resolve political conflicts’. States aggression is often occurs in this sphere of order as there are few limitations on war for states.

eliminate the potential for cooperation with other states. Pathways to order are designed through the development of social norms and collective order. Military instruments are still relevant, but are constrainted by many principles such as morality and sovereignty. This category of security order is less state-centric than instrumental order since it limitedly recognises the role and interests of non-state actors. It is even tolerates some cases of humanitarian intervention with the ‘consent of afected states.’ Goals in this order represent compromises between states interests and the community of states’ interests.

The third category of security order is a ‘solidarist security order’ which is the most ‘peaceful,’ prosperous, and ‘rules grounded’ (Wheeler and Dunne, 1996). This is where international society possesses strong social trust and ‘common values’ and ‘collective identities’ regarding not only on the importance of states but also individuals. ‘Trust and obligation’ are the main pathways to order where international law is the primary instrument of order. Individuals have reliable channels and adequate recognition to fight for their interests and security at the international level. There is also a functioning supranational governance in the form of a democratic security community to regulate international relations, although it is not a supranational government.

when promoting cooperation between states, although only with limited scope and commitment.

As illustrated in the figure of the spectrum of order shown below, Alagappa’s solidarist security order is slightly diferent from Bull’s solidarist moral order. Bull agrees with Alagappa that a pluralist order is more state centric and a solidarist order is more human centric.4

However, Bull and Alagappa have diferent emphases in defining and explaining the role of ‘moral ideas’. Alagappa tends to reduce the meaning of justice to ‘compliance to law’ because he attempts to create measurable indicators of order. In contrast, Bull clearly emphasises the importance in order building, of restoring justice rather than simply constituting law.5 He argues that ‘considerations of justice…are to be distinguished from considerations of law…’6 Justice goes beyond the formality of international law. Its scope includes so many values such as ‘general justice, particular justice, subtantive justice, arithmetical justice, proportionate justice, commutative justice and distributive justice.’7 These complex multiple dimensions of justice are not discussed in Alagappa’s spectrum. This suggests that Alagappa’s solidarist security order is not as solidarist as Bull’s. Alagappa’s solidarist security order might be located at intermediary zone between pluralist security order and solidarist moral order. For practical reason, this essay named Bull’s solidarist order as solidarist moral order.

This discussion reveals that order in international society ranges from instrumental order, normative-contractual order, solidarist security order, and solidarist moral order. The following figure illustrates how diferent conceptions of order from Bull’s and Alagappa’s spectra 4 Tim Dunne as quoted by Paul Keal, ‘An International Society?’, in Greg Fry

and Jacinta O’Hagan (eds), Contending Images of World Politics, London: MacMillan Press Ltd., 2000, p. 67.

5 Paul Keal, ‘An International Society?,’ p. 74.

6 Hedley Bull, The Anarchical Society, p. 75.

7 These concepts are explained in Hedley Bull, The Anarchical Society, pp.

complement one another.

Each sphere of order in this spectrum represents a particular conception of order which might be articulated diferently at diferent times by diferent actors. This spectrum is therefore a useful analytical tool that may be used to identify the types of order desired by actors in Southeast Asia. Further, this spectrum can also explain how ideas of order may change across time and context, and can help to shed light on/understand a discussion about which conception of order has been dominant at particular points in time and the consequences of this.

Challenges to ASEAN at the New Millennium III.

The ASEAN Charter was one of responses to some member states’ pessimism about ASEAN’s ability to deal with challenges in the 21st century. ASEAN was expected to do more than just maintain good diplomatic relations between its members (Nischalke, 2002). It was challenged to provide real solutions for old territorial disputes and to mitigate the negative impacts of non-traditional security issues. For this, ASEAN needed stronger commitments from its members in their implementation of regional agreements. The ASEAN charter was a response to this concern.

This crisis generated economic and social setbacks in Southeast Asia, particularly in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand (Emmerson, 2008). Inflation was out of control and many people lost their jobs. Social unrest occurred in many places. The impact also took on a political dimension as an Indonesian democratic movement found the momentum to depose Suharto. In Malaysia, a reform movement also rose but failed to bring about changes (Emmers, 2005). For ASEAN, this crisis forced them to admit ASEAN’s incapacity to respond to regional challenges. The crisis might not have been a severe if ASEAN had facilitated better regional coordination in multi sectors.

The second new challenge which contributed to the drafting of the ASEAN Charter was the continuing dilemma of Burma’s membership. ASEAN received condemnation from its Western dialogue partners for its inability to promote political change in Burma. Since 2003, ASEAN’s constructive engagement approach to Burma had been transformed into enhanced consultation. That is, ASEAN would provide advice on domestic issues which afected the common interests of all member states. However, the approach was considered to be useless because the Burmese Junta still did not give clear targets as to when and how a pathway to democracy would be accomplished.8 Thailand was also concerned by this since Burmese refugees kept crossing into Thailand and this caused insecurity along the Thai-Burma border. Burma’s domestic instability had increasingly disadvantaged the whole region.

The third new challenge behind the drafting of ASEAN Charter was transnational terrorism. Since the US war on terror in 2001 and the Bali Bombing in 2002, ASEAN states were alarmed by the close threat of terrorism in Southeast Asia. Both external pressures and intra-regional awareness of the transnational dimension of this threat motivated ASEAN to enhance its coordination in the intelligence and military sectors. As one of the root causes of terrorism was human

8 Amitav Acharya, ‘ASEAN at 40: Mid-Life Rejuvenation?’ Foreign Affairs,

insecurity in such forms as ‘poverty and injustice,’ ASEAN started to design a more ‘comprehensive’ approach to enhance regional

security (Emmers, 2005). The organisation realised that there should be real action and not just empty commitments in responding to this challenge.

Therefore, together the old and new challenges consisted of: old territorial disputes, the economic crisis, the dilemma of Burma, terrorism, and non-traditional problems, suggested that ASEAN needed a better compliance mechanism to bind member states to the regional agenda. ASEAN could not be an efective organisation if it could not do anything when member states deferred or violated their commitments. In this regard, ASEAN needed to design legalistic rules. A set of regulative norms with a clear distribution of rights and obligation were required, which would also provide clear rewards, as well as punishments as a disincentive for non-compliance.

Further, none of the above challenges could be solved through unitary and state-centric actions. They required partnership between states and peoples. This suggests that people were important subjects in regional security. Ignoring their aspirations could generate insecurities in the region. Actually, ASEAN had developed the ASEAN People’s Assembly (APA) in 2000. However, it excluded some people such as minority groups and government oppositions.9 The APA was also a weak initiative because there was no clear ‘link’ between this forum and ASEAN’s decision-making process.10 People still possessed

9 This was also called as the Track III diplomacy. Hadi Soesastro, ‘Introduction

and Summary,’ in Report of the Second ASEAN People’s Assembly, Challenges Facing the ASEAN People, Jakarta: Centre for Strategic and International Studies, 2003, p. 1.

10 It was also criticised for being dominated by the ASEAN Institute of Strategic

an insubstantial role and status in ASEAN.11

Realising the need for a compliance mechanism and a more people centric ASEAN, Malaysia proposed the drafting of an ASEAN Charter. It was an initiative to move towards a more people oriented and legalistic ASEAN. Malaysia proposed this idea in 2004, and in the following year ASEAN declared it part of the regional agenda at the Eleventh ASEAN Summit (Caballero-Anthony, 2008). Indeed, this idea raised considerable controversy within ASEAN between those states with diferent conceptions of order, as the next section will discuss.

Negotiating Order IV.

The drafting of the ASEAN Charter was controversial since adding both legal and human-centric elements could change the principal conceptions of order in the organisation. For some states, this change could be problematic. They sought new compromises in debates between diferent conceptions of order. Interestingly, societal and non-governmental representatives also participated in these debates. ASEAN formed The Eminent Persons Group (EPG) to draft a people’s recommendation for the ASEAN Charter. In drafting the recommendation, the EPG was to consult with civil society actors. The final draft would be sent to the High Level Task Force (HLTF), a body of government officials and former diplomats who had the duty of drafting the charter.12 This inclusion of civil society in the drafting of ASEAN Charter added more complexity to the debate between diferent conceptions of order.

There were at least three diferent conceptions of order that animated the debate over ASEAN community building. The first was a normative-contractual order. Its proponents insisted that the main

11 Kamarulzaman Askandar, Management and Resolution of Inter-State Conlicts in Southeast Asia, Malaysia: Southeast Asian Conlict Studies Network, 2002. 12 Pavin Chachavalpongpun (ed.), The Road to Ratiication and Implementation

purpose of order should be the preservation of sovereignty despite the risk of prolonging uncertainties in the region. A consideration of people’s political aspirations should be excluded at regional level because this was fell within the realm of domestic issues. Instead,

order should continue to be maintained through the balance of power management and the economic cooperation pathways to order. Those holding this conception of order basically resisted reforming the imperative of status quo norms as the main instruments of order. They were unwilling to adopt a more legalistic norms as such as the ASEAN Charter.

Burma was the main supporter of this conception of order. As a regime with problematic legitimacy domestically, this government preferred the strict application of status quo norms, and particularly non-interference norms (Nesandurai, 2009). The modification of non-interference norms with ASEAN’s constructive engagement and enhanced interactions were already placing Burma under political pressure (Nesandurai, 2009). More regulative and legal norms would require the Junta to fulfil its commitments since joining ASEAN, which included restoring democracy in Burma. In this regard, it was apparent that the Junta’s interests extremely against people’s interests.

Vietnam and Laos were not as inflexible as Burma in defending non-interference principle, but these states also favoured ASEAN’s conventional practices. These states were concerned that, after Burma, they would be the next targets of ASEAN’s condemnation for their human rights violations. Cambodia also held this state-centric conception of order, but it was not an assertive actor. As a weak democratic country, it was still unconfident about it its domestic stability. Its commitment to protection of human rights was also still vulnerable.

protections for people’s rights. The main pathway to order was the expansion of a liberal democratic regional community where peoples and states were partners. This revealed a desire to change ASEAN’s purposes and instruments from a state-oriented to people-oriented approach, and from a voluntary to a more legalistic approach. There were at least two consequences of this conception of order: the first was that ASEAN was expected to adopt mechanisms of sanction for non-compliance; and the second was that the principle of sovereignty was to be redefined. Sovereignty would be understood as ‘a responsibility to protect’ rather than rights to rule.13 It meant that interference would be acceptable in a case where a state failed to protect its citizens.

The main supporter of this main conception of order was the Eminent Persons Group (EPG) as a representative body of civil societies in the region. This body consulted with many diferent civil society groups in the region, including those who were outside APA.14 In its recommendation to the HLTF, the EPG proposed many institutional innovations such as: the establishment of a regional human rights mechanism, adoption of the responsibility to protect principle, a ‘non-consensus based decision-making process,’ the establishment of ‘consultative mechanism between people and ASEAN,’ the establishment of a sanction mechanism, and opposing ‘the unconstitutional change of government (Morada, 2008). The proposal reflected high expectations in civil society in Southeast Asia that ASEAN would substantially change its conception of order to be more people oriented.

Other supporters of this second aspiration for regional order were Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines. As democratic countries, these states were influenced by their people’s opinions. Thailand and 13 Noel Morada, ‘ASEAN at 40: Prospects for Community Building in

Southeast Asia, Asia-Paciic Review, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2008, p. 43.

14 There was a coalition of civil society actors outside APA namely Solidarity

the Philippines had proposed a reform of ASEAN’s non-interference principle since 1998 through the idea of ‘flexible engagement,’ a mechanism to allow ASEAN to become involved in promoting

solutions to member states’ domestic problems.15 They sought a more

efective mechanism for ASEAN to address regional problems. Among these states, Indonesia was the main supporter of the establishment of a regional human rights body, democratisation, promoting good governance and human security in Southeast Asia.16 It desired a regional order which could support its own democratisation .

The third vision of order in the drafting of the ASEAN Charter was a combination between a normative-contractual security order and a solidarist security order, described here as a thin solidarist security order. This conception of order entailed the protection and enhancement of individual rights and the elimination of conflict as the main purpose of order, but it did not include a non-compliance mechanism. Legal regulation was acceptable for supports of a thin solidarist security order, but it would only contain a distribution of rights and obligations; it would not include rewards and punishments. The main pathway to order in a thin solidarist security order was expansion of democratic community, but this was not a liberal democratic community. Although there would be a partnership between states and peoples, states would still have the stronger bargaining positions. State centrism was not problematic in this conception of order, as long as states could ensure that human security problems within their countries did not undermine regional security. People issues which had fewer regional implications would be excluded from legal arrangements, which indicated that pro status quo norms and state coexistence were also important goals and instruments of order. People issues were important because of their implications for order, but not because they were the main

15 Donald K. Emmerson, ‘The ASEAN Black Swans,’ op. cit. p. 77.

16 Rabea Volkmann, ‘Why does ASEAN Need a Charter? Pushing Actors and

‘stakeholders’ of order.17 A thin solidarist security order suggested

that ASEAN should be more people oriented but not as completely people oriented as in a liberal democratic community.

Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei Darussalam were the main supporters of this conception of order. While these states were aware that ASEAN needed better instruments to promote regional security, they were also cautious that ‘a people oriented ASEAN’ would stimulate democracy and human rights domestic movements. Ferguson argued that Malaysia and Singapore asserted that states’ legitimacy was derived from ‘output efects’ such as ‘economic growth, political stability and contained ethnic or minority tensions.’18 Brunei Darussalam had the same view with them. These states desired to improve their domestic human security conditions through improved economic welfare, but not through greater political liberty for their citizens.

This debate reveals the three main conceptions of order which competed in shaping the final draft of the ASEAN Charter, namely: a normative-contractual order, a solidarist security order, and a thin solidarist security order. Arguably, the idea of the ASEAN Charter was problematic for most ASEAN states because it included the element of people and legal sanctions. Even Malaysia, who was the initiator of the charter, was cautious of providing too much space for people’s aspirations in ASEAN. It seemed that the slogan of ‘a people oriented ASEAN,’ which dominated ASEAN rhetoric in the lead up to the signing of the charter, was interpreted in diferent ways by diferent member states. Democratic countries such as Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines perceived the ‘people’ as the main constituent of order, while the rest of the states perceived civil society as potential

17 The term ‘stakeholders of a community’ is borrowed from Michael E. Jones,

‘Forging an ASEAN Order: The Challenge to Construct Shared Destiny,’ Contemporary Southeast Asia, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2004, pp. 140-154.

18 R. James Ferguson, ‘ASEAN Concord II: Policy Prospects for Participant