INTRODUCTION . . . .xxvii

⊲ PART I

INTRODUCING XML

CHAPTER 1 What Is XML? . . . 3CHAPTER 2 Well-Formed XML . . . 25

CHAPTER 3 XML Namespaces . . . 53

⊲ PART II

VALIDATION

CHAPTER 4 Document Type Defi nitions . . . 83CHAPTER 5 XML Schemas . . . 117

CHAPTER 6 RELAX NG and Schematron. . . 175

⊲ PART III PROCESSING

CHAPTER 7 Extracting Data from XML . . . 211CHAPTER 8 XSLT . . . 239

⊲ PART IV DATABASES

CHAPTER 9 XQuery . . . 307CHAPTER 10 XML and Databases . . . 341

⊲ PART V PROGRAMMING

CHAPTER 11 Event-Driven Programming . . . 403CHAPTER 12 LINQ to XML . . . 451

⊲ PART VI COMMUNICATION

CHAPTER 13 RSS, Atom, and Content Syndication . . . 485CHAPTER 14 Web Services . . . 539

CHAPTER 15 SOAP and WSDL . . . 573

CHAPTER 18 Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) . . . 689

⊲ PART VIII CASE STUDY

CHAPTER 19 Case Study: XML in Publishing . . . 727APPENDIX A Answers to Exercises . . . 749

APPENDIX B XPath Functions . . . 773

APPENDIX C XML Schema Data Types . . . 797

XML

Joe Fawcett

Liam R.E. Quin

Danny Ayers

Indianapolis, IN 46256 www.wiley.com

Copyright © 2012 by Joe Fawcett, Liam R.E. Quin, and Danny Ayers

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Indianapolis, Indiana

Published simultaneously in Canada

ISBN: 978-1-118-16213-2 ISBN: 978-1-118-22612-4 (ebk) ISBN: 978-1-118-23948-3 (ebk) ISBN: 978-1-118-26409-6 (ebk)

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: The publisher and the author make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this work and specifi cally disclaim all warranties, including without limitation warranties of fi tness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales or promotional materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for every situation. This work is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional services. If professional assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. The fact that an organization or Web site is referred to in this work as a citation and/or a potential source of further information does not mean that the author or the publisher endorses the information the organization or Web site may provide or recommendations it may make. Further, readers should be aware that Internet Web sites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read.

For general information on our other products and services please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (877) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http:// booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2012937910

—

Joe Fawcett

Dedicated to Yuri Rubinsky, without whom there

would be no XML.

—

Liam Quin

Dedicated to my mother, Mary (because this will

amuse her no end).

JOE FAWCETT (http://joe.fawcett.name) has been writing software, on and off, for forty years. He was one of the fi rst people to be awarded the accolade of Most Valuable Professional in XML by Microsoft. Joe is head of software development for Kaplan Financial UK in London, which specializes in training people in business and accountancy and has one of the leading accountancy e-learning systems in the UK. This is the third title for Wrox that he has written in addition to the previous editions of this book.

LIAM QUIN (http://www.holoweb.net/~liam) is in charge of the XML work at the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). He has been involved with markup languages and text since the early 1980s, and was involved with XML from its inception. He has a background in computer science and digital typography, and also maintains a website dedicated to the love of books and illustrations at www.fromoldbooks.org. He lives on an old farm near Milford, in rural Ontario, Canada.

DANNY AYERS (http://dannyayers.com) is an independent researcher and developer of Web technologies, primarily those related to linked data. He has been an XML enthusiast since its early days. His background is in electronic music, although this interest has taken a back seat since the inception of the Web. Offl ine, he’s also an amateur woodcarver. Originally from the UK, he now lives in rural Tuscany with two dogs and two cats.

ABOUT THE TECHNICAL EDITOR

EXECUTIVE EDITOR Carol Long

PROJECT EDITOR Victoria Swider

TECHNICAL EDITOR Karen Tegtmeyer

PRODUCTION EDITOR Kathleen Wisor

COPY EDITOR Kim Cofer

EDITORIAL MANAGER Mary Beth Wakefi eld

FREELANCER EDITORIAL MANAGER Rosemarie Graham

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR OF MARKETING David Mayhew

MARKETING MANAGER Ashley Zurcher

BUSINESS MANAGER Amy Knies

PRODUCTION MANAGER Tim Tate

VICE PRESIDENT AND EXECUTIVE GROUP PUBLISHER

Richard Swadley

VICE PRESIDENT AND EXECUTIVE PUBLISHER Neil Edde

ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER Jim Minatel

PROJECT COORDINATOR, COVER Katie Crocker

PROOFREADERS

James Saturnio, Word One Sara Eddleman-Clute, Word One

INDEXER

Johnna VanHoose Dinse

COVER DESIGNER Ryan Sneed

I’D LIKE TO HEARTILY ACKNOWLEDGE the help of the editor Victoria Swider and the acquisitions editor Carol Long, who kept the project going when it looked as if it would never get fi nished. I’d like to thank the authors of the previous edition, especially Jeff Rafter and David Hunter, who let us build on their work when necessary. I’d also like to thank my wife Gillian and my children Persephone and Xavier for putting up with my absences and ill humor over the last year; I’ll make it up to you, I promise.

—Joe Fawcett

THANKS are due to my partner and to the pets for tolerating long and erratic hours, and of course to Alexander Chalmers, for creating the Dictionary of Biography in 1810.

—Liam Quin

MANY THANKS to Victoria, Carol, and the team for making everything work. Thanks too to Joe for providing the momentum behind this project and to Liam for keeping it going.

INTRODUCTION XXVII

PART I: INTRODUCING XML

CHAPTER 1: WHAT IS XML? 3

Steps Leading up to XML: Data Representation and Markups

4

Binary Files 4

Text Files 5

A Brief History of Markup 6

The Birth of XML

6

More Advantages of XML

10

XML Rules 10

Hierarchical Data Representation 11

Interoperability 12

XML in Practice

13

Data Versus Document 13

XML Scenarios 14

XML Technologies 16

Summary 23

CHAPTER 2: WELL-FORMED XML 25

What Does Well-Formed Mean?

26

Creating XML in a Text Editor

26

Forbidden Characters 26

XML Prolog 27

Creating Elements 30

Attributes 33

Element and Attribute Content 34

Processing Instructions 38

CDATA Sections 39

Advanced XML Parsing

40

XML Equivalence 41

Whitespace Handling 42

Error Handling 44

The XML Infoset

47

xvi

Element Information Items 48

Attribute Information Items 48

Processing Instruction Information Items 48

Character Information Item 49

Comment Information Item 49

Namespace Information Item 49

The Document Type Declaration Information Item 49

Unexpanded Entity Reference Information Item 49

Unparsed Entity Information Item 49

Notation Information Item 49

Summary 50

CHAPTER 3: XML NAMESPACES 53

Defi ning Namespaces

54

Why Do You Need Namespaces?

54

How Do You Choose a Namespace?

56

URLs, URIs, and URNs 56

Creating Your First Namespace 57

How to Declare a Namespace

58

How Exactly Does Scope Work? 62

Declaring More Than One Namespace 62

Changing a Namespace Declaration 64

Namespace Usage in the Real World

68

XML Schema 68

Documents with Multiple Namespaces 68

When to Use and Not Use Namespaces

72

When Namespaces are Needed 72

When Namespaces Are Not Needed 73

Versioning and Namespaces 74

Common Namespaces

75

The XML Namespace 75

The XMLNS Namespace 76

The XML Schema Namespace 76

The XSLT Namespace 76

The SOAP Namespaces 77

The WSDL Namespace 77

The Atom Namespace 77

The MathML Namespace 77

The Docbook Namespace 78

xvii

PART II: VALIDATION

CHAPTER 4: DOCUMENT TYPE DEFINITIONS 83

What Are Document Type Defi nitions?

83

Working with DTDs 84

Using jEdit 84

The Document Type Declaration in Detail 88

Sharing DTDs 92

Anatomy of a DTD

93

Element Declarations 93

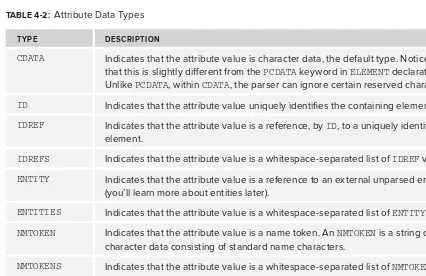

Attribute Declarations 103

Entity Declarations 109

DTD Limitations

114

Summary 114

CHAPTER 5: XML SCHEMAS 117

Benefi ts of XML Schemas

118

XML Schemas Use XML Syntax 118

XML Schema Namespace Support 118

XML Schema Data Types 119

XML Schema Content Models 119

XML Schema Specifi cations 119

XML Schemas in Practice

120

Defi ning XML Schemas

124

<schema> Declarations 124

<element> Declarations 128

Mixed Content 138

<group> Declarations 139

<attribute> Declarations 141

An XML Schema for Contacts 141

Data Types 148

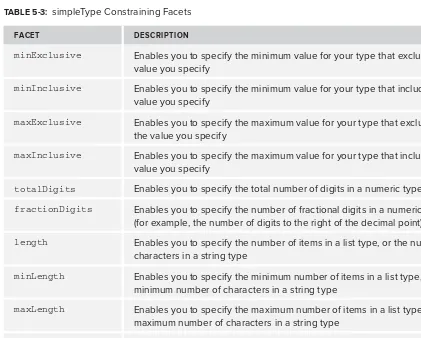

<simpleType> Declarations 155

Creating a Schema from Multiple Documents

161

<import> Declarations 161

<include> Declarations 165

Documenting XML Schemas

167

XML Schema 1.1

170

Relaxed Rules 170

<assert> 171

xviii

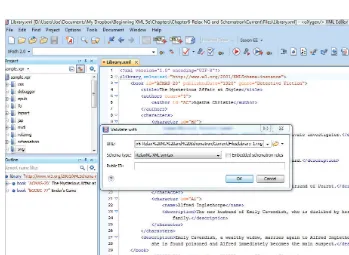

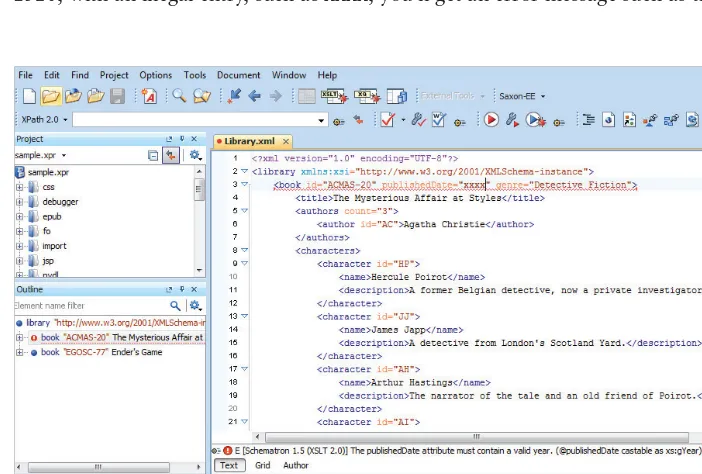

CHAPTER 6: RELAX NG AND SCHEMATRON 175

Why Do You Need More Ways of Validating XML?

176

Setting Up Your Environment

176

Using RELAX NG

177

Understanding the Basics of RELAX NG 177

Understanding RELAX NG’s Compact Syntax 183

Converting Between the Two RELAX NG Formats 185

Constraining Content 186

Reusing Code in RELAX NG Schema 189

Using Schematron

193

Understanding the Basics of Schematron 193

Choosing a Version of Schematron 194

Understanding the Basic Process 194

Writing Basic Rules in Schematron 195

Creating a Schematron Document 196

Adding More Information to Messages 197

Constraining Values in Schematron 200

Handling Co-Constraints in Schematron 202

Using Schematron from Within XML Schema 203

Summary 207

PART III: PROCESSING

CHAPTER 7: EXTRACTING DATA FROM XML 211

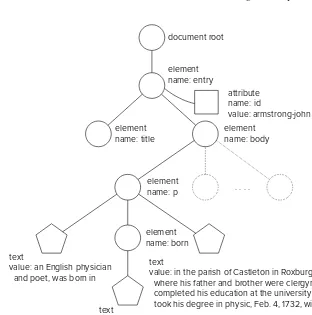

Document Models: Representing XML in Memory

211

Meet the Models: DOM, XDM, and PSVI 212

A Sample DOM Tree 212

DOM Node Types 213

DOM Node Lists 214

The Limitations of DOM 215

The XPath Language

216

XPath Basics 216

XPath Predicates: The Full Story 218

XPath Steps and Axes 220

XPath Expressions 222

Variables in XPath Expressions 226

New Expressions in XPath 2 227

xix

XPath Set Operations 234

XPath and Namespaces 234

Summary 236

CHAPTER 8: XSLT 239

What XSLT Is Used For

240

XSLT as a Declarative Language 240

How Is XSLT a Functional Language? 242

Setting Up Your XSLT Development Environment

242

Setting Up Saxon for .NET 243

Setting Up Saxon for Java 244

Foundational XSLT Elements

245

The <xsl:stylesheet> Element 246

The <xsl:template> Element 247

The <xsl:apply-templates> Element 251

The <xsl:value-of> Element 251

The <xsl:for-each> Element 253

Push-Processing versus Pull-Processing 254

The Role of XPath in XSLT 254

Using Named Templates 256

The <xsl:call-template> Element 259

The document() Function in XSLT 260

Conditional Logic 266

The <xsl:param> element 270

The <xsl:sort> Element 271

<xsl:copy> and <xsl:copy-of> Elements 273

Reusing Code in XSLT

276

The <xsl:include> Element 276

The <xsl:import> Element 279

The <xsl:template> Mode Attribute 280

Understanding Built-In Templates and Built-In Rules

282

Using XSLT 2.0

284

Understanding Data Types in XSLT 2.0 285

Creating User-Defi ned Functions 285

Creating Multiple Output Documents 290

Using the collection() Function 291

Grouping in XSLT 2.0 292

Handling Non-XML Input with XSLT 2.0 295

xx

PART IV: DATABASES

CHAPTER 9: XQUERY 307

XQuery, XPath, and XSLT

308

XQuery and XSLT 308

XQuery and XPath 308

XQuery in Practice

309

Standalone XQuery Applications 309

Part of SQL 309

Callable from Java or Other Languages 309

A Native-XML Server 310

XQuery Anywhere 310

Building Blocks of XQuery

313

FLWOR Expressions, Modules, and Functions 313

XQuery Expressions Do Not Have a Default Context 317

The Anatomy of a Query Expression

318

The Version Declaration 318

The Query Prolog 319

The Query Body 325

Some Optional XQuery Features

332

XQuery and XPath Full Text 332

The XQuery Update Facility 333

XQuery Scripting Extension 333

Coming in XQuery 3.0

333

Grouping and Windowing 334

The count Clause 335

Try and Catch 335

switch Expressions 336

Function Items and Higher Order Functions 337

JSON Features 338

XQuery, Linked Data, and the Semantic Web 338

Summary 338

CHAPTER 10: XML AND DATABASES 341

Understanding Why Databases Need to Handle XML

341

Analyzing which XML Features are Needed in a Database

343

Retrieving Documents 343

Retrieving Data from Documents 343

Updating XML Documents 344

Displaying Relational Data as XML 344

xxi

Using MySQL with XML

345

Installing MySQL 345

Adding Information in MySQL 345

Querying MySQL 348

Updating XML in MySQL 353

Usability of XML in MySQL 353

Client-Side XML Support 354

Using SQL Server with XML

355

Installing SQL Server 355

Presenting Relational Data as XML 356

Understanding the xml Data Type 371

Creating Indexes with the xml Data Type 374

W3C XML Schema in SQL Server 384

Dealing with Namespaced Documents 385

Using eXist with XML

386

Downloading and Installing eXist 387

Interacting with eXist 389

Summary 399

PROGRAMMING

PART V: PROGRAMMING

CHAPTER 11: EVENT-DRIVEN PROGRAMMING 403

Understanding Sequential Processing

404

Using SAX in Sequential Processing

404

Preparing to Run the Examples 405

Receiving SAX Events 406

Handling Invalid Content 417

Using the DTDHandler Interface 427

EntityResolver Interface 428

Understanding Features and Properties 429

Using XmlReader

434

Using XmlReaderSettings 441

Controlling External Resources 447

Summary 448

CHAPTER 12: LINQ TO XML 451

What Is LINQ?

451

Why You Need LINQ to XML 454

xxii

Creating Documents

457

Creating Documents with Namespaces 459

Creating Documents with Prefi xed Namespaces 460

Extracting Data from an XML Document

461

Modifying Documents

468

Adding Content to a Document 468

Removing Content from a Document 470

Updating and Replacing Existing Content in a Document 470

Transforming Documents

472

Using VB.NET XML Features

474

Using VB.NET XML Literals 474

Understanding Axis Properties in VB.NET 478

Managing Namespaces in VB.NET 480

Summary 480

PART VI: COMMUNICATION

CHAPTER 13: RSS, ATOM, AND CONTENT SYNDICATION 485

Syndication

485

XML Syndication 486

Syndication Systems 488

Format Anatomy 491

Working with News Feeds

501

Newsreaders 501

Data Quality 501

A Simple Aggregator

502

Modeling Feeds 502

Program Flow 505

Implementation 505

Extending the Aggregator 521

Transforming RSS with XSLT

524

Generating a Feed from Existing Data 524

Processing Feed Data for Display 528

Browser Processing 531

Preprocessing Feed Data 532

Reviewing the Diff erent Formats 532

Useful Resources

534

xxiii

CHAPTER 14: WEB SERVICES 539

What Is an RPC?

539

RPC Protocols

541

COM and DCOM 541

COBRA and IIOP 542

Java RMI 543

The New RPC Protocol: Web Services

543

The Same Origin Policy 544

Understanding XML-RPC 546

Choosing a Network Transport 548

Understanding REST Services 559

The Web Services Stack

564

SOAP 565 WSDL 566 UDDI 566

Surrounding Specifi cations 567

Summary 569

CHAPTER 15: SOAP AND WSDL 573

Laying the Groundwork

574

The New RPC Protocol: SOAP

574

Comparing SOAP to REST 579

Basic SOAP Messages 579

More Complex SOAP Interactions 587

Defi ning Web Services: WSDL

600

<defi nitions> 601

<types> 601 <messages> 602 <portTypes> 602 <binding> 603 <service> 605

Other Bindings 609

Summary 612

CHAPTER 16: AJAX 615

AJAX Overview

615

AJAX Provides Feedback 616

Loading Incomplete Data With AJAX 616

xxiv

Introduction to JavaScript

617

The Web Browser Console 618

Values, Expressions, and Variables 619

Control Flow Statements 621

Properties, Objects, Functions and Classes 622

The XMLHttpRequest Function

623

Using HTTP Methods with AJAX

628

Accessibility Considerations

629

The jQuery Library

630

Learning jQuery 631

The Domain-Specifi c Language (DSL) Approach 631

jQuery Plug-ins and Add-On Libraries 632

JSON and AJAX

635

JSON Example 635

JSON Syntax 636

JSON and jQuery 636

JSONP and CORS 637

The Web Sever Back End

637

Sending Images and Other Non-Textual Data 638

Performance 638

The Server Logs Are Your Friend 639

A Larger Example

639

Summary 644

PART VII: DISPLAY

CHAPTER 17: XHTML AND HTML 5 649

Background of SGML

650

HTML and SGML 650

XML and SGML 651

The Open Web Platform

651

Introduction to XHTML

652

The XHTML <html> Element 653

The XHTML <head> Element 654

The XHTML <body> Element 656

More Advanced HTML Topics 668

XHTML and HTML: Problems and Workarounds

669

Cascading Style Sheets (CSS)

670

CSS Levels and Versions 670

CSS at a Glance 671

CSS Selectors 673

xxv

CSS Special Rules 680

CSS and XML 681

Separating Style and Markup: Unobtrusive CSS 682

Unobtrusive JavaScript

682

HTML 5

683

Benefi ts of HTML 5 683

Caveats of HTML 5 683

New Elements in HTML 5 684

Summary 686

CHAPTER 18: SCALABLE VECTOR GRAPHICS (SVG) 689

Scalable Vector Graphics and Bitmaps

689

Procedural Graphics 690

Declarative Graphics 690

Bitmap Graphics 691

Vector Images 692

SVG Images 692

The SVG Graphics Model

694

SVG and CSS

696

SVG Tools

698

SVG Basic Built-in Shapes

700

Rectangles 701 Circles 702 Ellipses 702

Straight Lines 703

Polylines and Polygons 704

SVG Paths 705

SVG Transforms and Groups

708

Transforms 708 Groups 709

SVG Defi nitions and Metadata

709

The SVG <title> and <desc> Elements 709

The SVG <metadata> Element 710

The SVG <defs> Element and Reusable Content 711

Viewports and Coordinates

712

SVG Colors and Gradients

713

Including Bitmap Images in SVG

715

SVG Text and Fonts

716

SVG Animation Four Ways

717

Synchronized Multimedia Integration Language (SMIL) 718

xxvi

CSS Animation 719

External Libraries 720

SVG and HTML 5

720

SVG and Web Apps

721

Making SVG with XQuery or XSLT

722

Resources 722

Summary 723

PART VIII: CASE STUDY

CHAPTER 19: CASE STUDY: XML IN PUBLISHING 727

Background 727

Project Introduction: Current Workfl ow

728

Introducing a New XML-Based Workfl ow

728

Consultations 729

Documenting the Project 729

Prototyping 729

Creating a New Process

730

Challenging Criteria 730

The New Workfl ow 731

Document Conversion and Technologies 731

Costs and Benefi ts Analysis 732

Deployment 733

Some Technical Aspects

733

XQuery and Modules 734

XInclude 734

Equations and MathML 734

XProc: An XML Pipelining Language 737

XForms, REST, and XQuery 738

Formatting to PDF with XSL-FO 738

XML Markup for Documentation 741

Markup for the Humanities: TEI 741

The Hoy Books Website

741

Summary 746

APPENDIX A: ANSWERS TO EXERCISES 749

APPENDIX B: XPATH FUNCTIONS 773

APPENDIX C: XML SCHEMA DATA TYPES 797

THIS IS THE FIFTH EDITION OF A BOOK that has proven popular with professional developers and academic institutions. It strives to impart knowledge on a subject that at fi rst was seen by some as just another fad, but that instead has come to maturity and is now often just taken for granted. Almost six years have passed since the previous edition — a veritable lifetime in IT terms. In review-ing the fourth edition for what should be kept, what should be updated, and what new material was needed, the current authors found that about three-quarters of the material was substantially out of date. XML has far more uses than fi ve years ago, and there is also much more reliance on it under the covers. It is now no longer essential to be able to handcraft esoteric confi guration fi les to get a web service up and running. It has also been found that, in some places, XML is not always the best fi t. These situations and others, along with a complete overhaul of the content, form the basis for this newer version.

So, what is XML? XML stands for eXtensible Markup Language, which is a language that can be used to describe data in a meaningful way. Virtually anywhere there is a need to store data, especially where it may need to be consumed by more than one application, XML is a good place to start. It has gained a reputation for being a candidate where interoperability is important, either between two applications in different businesses or simply those within a company. Hundreds of standardized XML formats now exist, known as schemas, which have been agreed on by

businesses to represent different types of data, from medical records to fi nancial transactions to GPS coordinates representing a journey.

WHO THIS BOOK IS FOR

This book aims to suit a fairly wide range of readers. Most developers have heard of XML but may have been a bit afraid of it. XML has a habit nowadays of being used behind the scenes, and it’s only when things don’t work as expected or when developers want to do something a little different, that users start to realize that they must open the hood. To those people we say: fear no longer. It should also suit the developer experienced in other fi elds who has never had a formal grounding in the subject. Finally, it can be used as reference when you need to try something out for the fi rst time. Nearly all the technologies in the book have a Try It Out section associated with them that fi rst gets you up and running with a simple example and then explains how to progress from there.

What you don’t need for this book is any knowledge of markup languages in general. This is all covered in the fi rst few chapters. It is expected that most of the readership will have some knowledge of and experience with web programming, but we’ve tried to spread our examples so that knowledge could include using the Microsoft stack, Java, or one of the other open source frameworks, such as PHP or Python.

xxviii

WHAT THIS BOOK COVERS

This book aims to teach you all you need to know about XML — what it is, how it works, what technologies accompany it, and how you can make it work for you, from simple data transfer to a way to provide multi-channeled content. The book sets out to answer these fundamental questions:

➤ What is XML?

➤ How do you use XML? ➤ How does it work? ➤ What can you use it for?

The basic concepts of XML have remained unchanged since their launch, but the surrounding technologies have changed dramatically. This book gives a basic overview of each technology and how it arose, but the majority of the examples use the latest version available. The examples are also drawn from more than one platform, with Java and .NET sharing most of the stage. XML products have also evolved; at one time there were many free and commercial Extensible Stylesheet Language Transformation (XSLT) processors; for example, XSLT is used to manipulate XML, changing it from one structure to another, and is covered in Chapter 8, but since version 2 appeared the number has reduced considerably as the work needed to develop and maintain the software has risen.

HOW THIS BOOK IS STRUCTURED

We’ve tried to arrange the subjects covered in this book to lead you along the path of novice to expert in as logical a manner as possible. The sections each cover a different area of expertise. Unless you’re fairly knowledgeable about the basics, we suggest you read the introductory chapters in Part 1, although skimming through may well be enough for the savvier user. The other sections can then be read in order or can be targeted directly if they cover an area that you are particularly interested in. For example, when your boss suddenly tells you that your next release must offer an XQuery add-in, you can head straight to Chapter 9. A brief overview of the book is as follows:

➤ You begin by learning exactly what XML is and why people felt it was needed. ➤ We then take you through how to create XML and what rules need to be followed. ➤ Once you’ve mastered that, you move on to what a valid XML document is and how you

can be sure that yours is one of them.

➤ Then you’ll look at how you can manipulate XML documents to extract data and to trans-form them into other trans-formats.

➤ Next you deal with storing XML in databases — the advantages and disadvantages and how to query them when they’re there.

xxix

➤ We then cover some uses of XML, how to publish data in an XML format, and how to create and consume XML-based web services. We explain how AJAX came about and how it works, alongside some alternatives to XML and when you should consider them.

➤ We follow up with a couple of chapters on how to use XML for web page and image display.

➤ Finally, there’s a case study that ties a lot of the various XML-based technologies together into a real-world example.

We’ve tried to organize the book in a logical fashion, such that you are introduced to the basics and then led through the different technologies associated with XML. These technologies are grouped into six sections covering most of topics that you’ll encounter with XML, from validation of the original data to processing, storage, and presentation.

Part I: Introduction

This is where most readers should start. The chapters in this part cover the goals of XML and the rules for constructing it. After reading this part you should understand the basic concepts and terminology. If you are already familiar with XML, you can probably just skim these chapters.

Chapter 1: What Is XML? — Chapter 1 covers the history of XML and why it is needed, as well as the basic rules for creating XML documents.

Chapter 2: Well-Formed XML — This chapter goes into more detail about what is and isn’t allowed if a document is to be called XML. It also covers the modern naming system that is used to describe the different constituent parts of an XML document.

Chapter 3: XML Namespaces — Everyone’s favorite, the dreaded topic of namespaces, is explained in a simple-to-understand fashion. After reading this chapter, you’ll be the expert while everyone else is scratching their heads.

Part II: Validation

This part covers different techniques that help you verify that the XML you’ve created, or received, is in the correct format.

Chapter 4: Document Type Defi nitions — DTDs are the original validation mechanism for XML. This chapter shows how they are used to both constrain the document and to supply additional content.

Chapter 5: XML Schemas — XML Schemas are the more modern way of describing an XML document’s format. This chapter examines how they work and discusses the advantages and disadvantages over DTDs.

xxx

Part III: Processing

This section covers retrieving data from an XML document and also transforming one format of XML to another. Included is a thorough grounding in XPath, one of the cornerstones of many XML technologies.

Chapter 7: Extracting Data from XML — This chapter covers the document object model (DOM), one of the earliest ways devised to extract data from XML. It then goes on to describe XPath, one of the cornerstone XML technologies that can be used to pinpoint one or many items of interest.

Chapter 8: XSLT — XSLT is a way to transform XML from one format to another, which is essential if you are receiving documents from external sources and need your own systems to be able to read them. It covers the basics of version 1, the more advanced features of the current version, and shows a little of what’s scheduled in the next release.

Part IV: Databases

For many years there has been a disparity between data held in a database and that stored as XML. This part brings the two together and shows how you can have the best of both worlds.

Chapter 9: XQuery — XQuery is a mechanism designed to query existing documents and create new XML documents. It works especially well with XML data that is stored in databases, and this chapter shows how that’s done.

Chapter 10: XML and Databases — Many database systems now have functionality designed especially for XML. This chapter examines three such products and shows how you can both query and update existing data as well as create new XML, should the need arise.

Part V: Programming

This part looks at two programming techniques for handling XML. Chapter 11 covers dealing with large documents, and Chapter 12 shows how Microsoft’s latest universal data access strategy, LINQ, can be used with XML.

Chapter 11: Event-Driven Programming — This chapter looks at two different ways of handling XML that are especially suited to processing large fi les. One is based on an open source API and the examples are implemented in Java. The second is a key part of Microsoft’s .NET Framework and shows examples in C#.

Chapter 12: LINQ to XML — This chapter shows Microsoft’s latest way of handling XML, from creation to querying and transformation. It contains a host of examples that use both C# and VB.NET, which, for once, currently has more features than its .NET cousin.

Part VI: Communication

xxxi

Chapter 13: RSS, Atom, and Content Syndication — This chapter covers the two main ways in which content, such as news feeds, is presented in a platform-independent fashion. It also covers how the same XML format can be used to present structured data such as customer listings or sales results.

Chapter 14: Web Services — One of the biggest software success stories over the past ten years has been web services. This chapter examines how they work and where XML fi ts into the picture, which is essential knowledge, should things start to go wrong.

Chapter 15: SOAP and WSDL — This chapter burrows down further into web services and describes two major systems used within them: SOAP, which dictates how

services are called, and Web Services Description Language (WSDL), which is used to describe what a web service has to offer.

Chapter 16: AJAX — The fi nal chapter in this section deals with AJAX and how it can help your website provide up-to-the-minute information, yet remain responsive and use less bandwidth. Obviously XML is involved, but the chapter also examines the situations when you’d want to abandon XML and use an alternative technology.

Part VII: Display

This part shows two ways in which XML can help display information in a user-friendly form as well as in a format that can be read by a machine.

Chapter 17: XHTML and HTML 5 — This chapter covers how and where to use XHTML and why it is preferred over traditional HTML. It then goes on to show the newer features of HTML 5 and how it has removed some of these obstacles.

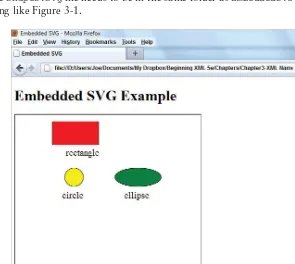

Chapter 18: Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) — This chapter shows how images can be stored in an XML format and what the advantages are to this method. It then shows how this format can be combined with others, such as HTML, and why you would do this.

Part VIII: Case Study

This part contains a case study that ties in the many uses of XML and shows how they would interact in a real-world example.

Chapter 19: Case Study: XML in Publishing — The case study shows how a fi ctional publishing house goes from proprietary-based publishing software to an XML-based workfl ow and what benefi ts this brings to the business.

Appendices

The three appendices contain reference material and solutions to the end-of-chapter exercises.

Appendix A: Answers to Exercises — This appendix contains solutions and suggestions for the end-of-chapter exercises that have appeared throughout the book.

Appendix B: XPath Functions — This appendix contains information on the majority of XPath functions, their signatures, return values, and examples of how and where you would use them.

xxxii

WHAT YOU NEED TO USE THIS BOOK

There’s no need to purchase anything to run the examples in this book; all the examples can be written with and run on freely available software. You’ll need a machine with a standard browser — Internet Explorer, Firefox, Chrome, or Safari should do as long it’s one of the more recent editions. You’ll need a basic text editor, but even Notepad will do if you want to create the examples rather than just download them from the Wrox site. You’ll also need to run a web server for some of the code, either the free version of IIS for Windows or one of the many open source implementations such as Apache for other systems will do. For some of the coding examples you’ll need Visual Studio. You can either use a commercial version or the free one available for download from Microsoft.

If you want to use the free version, Visual Studio Express 2010, then head to www.microsoft.com/ visualstudio/en-us/products/2010-editions/express. Each edition of Visual Studio concen-trates on a specifi c area such as C# or web development, so to try all the examples you’ll need to download the C# edition, the VB.NET edition, and the Web edition. You should also install service pack 1 for Visual Studio 2010 which can be found at www.microsoft.com/ download/en/details .aspx?id=23691. Once everything is installed you’ll be able to open the sample solutions or, failing that, one of the sample projects within the solutions by Choosing File ➪ Open ➪ Project/Solution . . . and browsing to either the solution fi le or the specifi c project you want to run. As this book went to press Microsoft was preparing to release a new version, Visual Studio 2011. The examples in this book should all work with this newer version although the screenshots may differ slightly.

CONVENTIONS

To help you get the most from the text and keep track of what’s happening, we’ve used a number of conventions throughout the book.

TRY IT OUT

The Try It Out is an exercise you should work through, following the text in the book.

1.

They usually consist of a set of steps.2.

Each step has a number.3.

Follow the steps through with your copy of the database.How It Works

After each Try It Out, the code you’ve typed will be explained in detail.

xxxiii

As for styles in the text:

➤ We highlight new terms and important words when we introduce them. ➤ We show keyboard strokes like this: Ctrl+A.

➤ We show fi lenames, URLs, and code within the text like so: persistence.properties. ➤ We present code in two different ways:

We use a monofont type with no highlighting for most code examples.

We use bold to emphasize code that’s particularly important in the present context.

SOURCE CODE

As you work through the examples in this book, you may choose either to type in all the code manually, or to use the source code fi les that accompany the book. All the source code used in this book is available for download at www.wrox.com. When at the site, simply locate the book’s title (use the Search box or one of the title lists) and click the Download Code link on the book’s detail page to obtain all the source code for the book. Code that is included on the website is highlighted by the following icon:

Available for download on Wrox.com

Listings include the fi lename in the title. If it is just a code snippet, you’ll fi nd the fi lename in a code note such as this:

fi lename

NOTE Because many books have similar titles, you may fi nd it easiest to search by ISBN; this book’s ISBN is 978-1-118-16213-2.

NOTE The pencil icon indicates notes, tips, hints, tricks, and asides to the current discussion.

xxxiv

ERRATA

We make every effort to ensure that there are no errors in the text or in the code. However, no one is perfect, and mistakes do occur. If you fi nd an error in one of our books, like a spelling mistake or faulty piece of code, we would be very grateful for your feedback. By sending in errata you may save another reader hours of frustration and at the same time you will be helping us provide even higher quality information.

To fi nd the errata page for this book, go to www.wrox.com and locate the title using the Search box or one of the title lists. Then, on the book details page, click the Book Errata link. On this page you can view all errata that has been submitted for this book and posted by Wrox editors. A complete book list including links to each book’s errata is also available at www.wrox.com/

misc-pages/booklist.shtml.

If you don’t spot “your” error on the Book Errata page, go to www.wrox.com/contact/

techsupport.shtml and complete the form there to send us the error you have found. We’ll check the information and, if appropriate, post a message to the book’s errata page and fi x the problem in subsequent editions of the book.

P2P.WROX.COM

For author and peer discussion, join the P2P forums at p2p.wrox.com. The forums are a web-based system for you to post messages relating to Wrox books and related technologies and interact with other readers and technology users. The forums offer a subscription feature to e-mail you topics of interest of your choosing when new posts are made to the forums. Wrox authors, editors, other industry experts, and your fellow readers are present on these forums.

At http://p2p.wrox.com, you will fi nd a number of different forums that will help you not only as you read this book, but also as you develop your own applications. To join the forums, just follow these steps:

1.

Go to p2p.wrox.com and click the Register link.2.

Read the terms of use and click Agree.3.

Complete the required information to join as well as any optional information you wish to provide and click Submit.4.

You will receive an e-mail with information describing how to verify your account and complete the joining process.xxxv

Introducing XML

⊲

CHAPTER 1:

What Is XML?

⊲

CHAPTER 2:

Well-Formed XML

What Is XML?

WHAT YOU’LL WILL LEARN IN THIS CHAPTER:

➤ The story before XML ➤ How XML arrived

➤ The basic format of an XML document ➤ Areas where XML is useful

➤ A brief introduction to the technologies surrounding, and associated with, XML

XML stands for Extensible Markup Language (presumably the original authors thought that sounded more exciting than EML) and its development and usage have followed a com-mon path in the software and IT world. It started out more than ten years ago and was originally used by very few; later it caught the public eye and began to pervade the world of data exchange. Subsequently, the tools available to process and manage XML became more sophisticated, to such an extent that many people began to use it without being really aware of its existence. Lately there has been a bit of a backlash in certain quarters over its perceived failings and weak points, which has led to various proposed alternatives and improvements. Nevertheless, XML now has a permanent place in IT systems and it’s hard to imagine any non-trivial application that doesn’t use XML for either its confi guration or data to some degree. For this reason it’s essential that modern software developers have a thorough under-standing of its principles, what it is capable of, and how to use it to their best advantage. This book can give the reader all those things.

NOTE Although this chapter presents some short examples of XML, you aren’t expected to understand all that’s going on just yet. The idea is simply to intro-duce the important concepts behind the language so that throughout the book you can see not only how to use XML, but also why it works the way it does.

STEPS LEADING UP TO XML: DATA REPRESENTATION

AND MARKUPS

There are two main uses for XML: One is a way to represent low-level data, for example confi gura-tion fi les. The second is a way to add metadata to documents; for example, you may want to stress a particular sentence in a report by putting it in italics or bold.

The fi rst usage for XML is meant as a replacement for the more traditional ways this has been done before, usually by means of lists of name/value pairs as is seen in Windows’ INI or Java’s Property fi les. The second application of XML is similar to how HTML fi les work. The document text is con-tained in an overall container, the <body> element, with individual phrases surrounded by <i> or <b> tags. For both of these scenarios there has been a multiplicity of techniques devised over the years. The problem with these disparate approaches has been more apparent than ever, since the increased use of the Internet and extensive existence of distributed applications, particularly those that rely on components designed and managed by different parties. That problem is one of intercommunication. It’s certainly possible to design a distributed system that has two components, one outputting data using a Windows INI fi le and the other which turns it into a Java Properties format. Unfortunately, it means a lot of development on both sides, which shouldn’t really be necessary and detracts resources from the main objective, developing new functionality that delivers business value.

XML was conceived as a solution to this kind of problem; it is meant to make passing data between different components much easier and relieve the need to continually worry about different formats of input and output, freeing up developers to concentrate on the more important aspects of coding such as the business logic. XML is also seen as a solution to the question of whether fi les should be easily readable by software or by humans; XML’s aim is to be both. You’ll be examining the distinc-tion between data-oriented and document-centric XML later in the book, but for now let’s look a bit more deeply into what the choices were before XML when there was need to store or communi-cate data in an electronic format.

This section takes a mid-level look at data representation, without taking too much time to explain low-level details such as memory addresses and the like. For the purposes here you can store data in fi les two ways: as binary or as text.

Binary Files

For example, when saving a document in Microsoft Word, using a version before 2003, the fi le cre-ated (which has a doc extension) is in a binary format. If you open the fi le in a text editor such as Notepad, you won’t be able to see a picture of the original Word document; the best you’ll be able to see is the occasional line of text surrounded by gibberish rather than the prose, which could be in a number of formats such as bold or italic. The characters in the document other than the actual text are metadata, literally information about information. Mixing data and metadata is both common and straightforward in a binary fi le. Metadata can specify things such as which words should be shown in bold, what text is to be displayed in a table, and so on. To interpret this fi le you the need the help of the application that created it. Without the help of a converter that has in-depth knowl-edge of the underlying binary format, you won’t be able to open a document created in Word with another similar application such as WordPerfect. The main advantage of binary formats is that they are concise and can be expressed in a relatively small space. This means that more fi les can be stored (on a hard drive, for example) but, more importantly nowadays, less bandwidth is used when trans-porting these fi les across networks.

Text Files

The main difference between text and binary fi les is that text fi les are human and machine readable. Instead of a proprietary format that needs a specifi c application to decipher it, the data is such that each group of bits represents a character from a known set. This means that many different applica-tions can read text fi les. On a standard Windows machine you have a choice of Notepad, WordPad, and others, including being able to use command-line–based utilities such as Edit. Non-Windows machines have a similar wide range insert of programs available, such as Emacs and Vim.

NOTE The way that characters are represented by the underlying data stream is referred to as a fi le’s encoding. The specifi c encoding used is often present as the fi rst few bytes in the fi le; an application checks these bytes upon opening the fi le and then knows how to display and manipulate the data. There is also a default encoding if these fi rst few bytes are not present. XML also has other ways of specifying how a fi le was encoded, and you’ll see these later on.

The ability to be read and understood by both humans and machines is not the only advantage of text fi les; they are also comparatively easier to parse than binary fi les. The main disadvantage however, is their size. In order for text fi les to contain metadata (for example, a stretch of text to be marked as important), the relevant words are usually surrounded by characters denoting this extra information, which are somehow differentiated from the actual text itself. The most common exam-ples of this can be found in HTML, where angle brackets are special symbols used to convey the meaning that anything within them refers to how the text should be treated rather than the actual data. For example, if I want mark a phrase as important I can wrap it like so:

Another disadvantage of text fi les is their lack of support for metadata. If you open a Word docu-ment that contains text in an array of fonts with different styles and save it as a text fi le, you’ll just get a plain rendition; all of the metadata has been lost. What people were looking for was some way to have the best of both worlds — a human-readable fi le that could also be read by a wide range of applications, and could carry metadata along with its content. This brings us to the subject of markup.

A Brief History of Markup

The advantages of text fi les made it the preferred choice over binary fi les, yet the disadvantages were still cumbersome enough that people wanted to also standardize how metadata could be added. Most agreed that markup, the act of surrounding text that conveyed information about the text, was the way forward, but even with this agreed there was still much to be decided. The main two questions were:

➤ How can metadata be differentiated from the basic text? ➤ What metadata is allowed?

For example, some documents needed the ability to mark text as bold or italic whereas others were more concerned with who the original document author was, when was it created, and who had subsequently modifi ed it. To cope with this problem a defi nition called Standard Generalized Markup Language was released, commonly shortened to SGML. SGML is a step removed from defi ning an actual markup language, such as the Hyper Text Markup Language, or HTML. Instead it relays how markup languages are to be defi ned. SGML allows you to create your own markup language and then defi ne it using a standard syntax such that any SGML-aware application can consume documents written in that language and handle them accordingly. As previously noted, the most ubiquitous example of this is HTML. HTML uses angular brackets (< and >) to separate metadata from basic text and also defi nes a list of what can go into these brackets, such as em for emphasizing text, trfor table, and td for representing tabular data.

THE BIRTH OF XML

NOTE The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) is the main international stan-dards organization for the World Wide Web. It has a number of working groups targeting diff erent aspects of the Web that discuss standardization and docu-mentation of the diff erent technologies used on the Internet. The standards doc-uments go through various stages such as Working Draft and Candidate Recommendation before fi nally becoming a Recommendation. This process can take many years. The reason that the fi nal agreement is called a recommenda-tion rather than a standard is that you are still free to ignore what it says and use your own. All web developers know the problems in developing applications that work across all browsers, and many of these problems arise because the browser vendors did not follow a W3C recommendation or they did not imple-ment features before the recommendation was fi nalized. Most of the XML tech-nologies discussed in this book have a W3C recommendation associated with them, although some don’t have a full recommendation because they are still in draft form. Additionally, some XML-related standards originate from outside the W3C, such as SAX which is discussed in Chapter 11, “Event Driven Programming.” and therefore they also don’t have offi cial W3C recommendations.

XML therefore derived as a subset of SGML, whereas HTML is an application of SGML. XML doesn’t dictate the overall format of a fi le or what metadata can be added, it just specifi es a few rules. That means it retains a lot of the fl exibility of SGML without most of the complexity. For example, suppose you have a standard text fi le containing a list of application users:

Joe Fawcett Danny Ayers

Catherine Middleton

This fi le has no metadata; the only reason you know it’s a list of people is your own knowledge and experience of how names are typically represented in the western world. Now look at these names as they might appear in an XML document:

<applicationUsers>

<user firstName=”Joe” lastName=”Fawcett” /> <user firstName=”Danny” lastName=”Ayers” />

<user firstName=”Catherine” lastName=”Middleton” /> </applicationUsers>

Immediately it’s more apparent what the individual pieces of data are, although an application still wouldn’t know just from that fi le how to treat a user or what firstName means. Using the XML format rather than the plain text version, it’s much easier to map these data items within the appli-cation itself so they can be handled correctly.

A big disadvantage of this metadata, however, is the consequent increase in the size of the fi le. The metadata adds about 130 extra characters to the fi le’s original 43 character size, an increase of more than 300 percent. The creators of XML decided that the power of metadata warranted this increase and, indeed, one of their maxims during the design was that terseness is not an aim, a decision that many would later come to regret.

NOTE Later on in the book you’ll see a number of ways to minimize the size of an XML fi le if needed. However, all these methods are, to some extent, a trade-off against readability and ease of use.

Following is a simple exercise to demonstrate the differences in how applications handle simple text fi les against how XML is treated. Even though the application, in this case a browser, is told noth-ing in advance of opennoth-ing the two fi les, you’ll see how much more metadata is available in the XML version compared to the text one.

TRY IT OUT

Opening an XML File in a Browser

This example shows the differences in how XML fi les can be handled compared to plain text fi les.

1.

Create a new text fi le in Notepad, or an equivalent simple text editor, and paste in the list ofnames fi rst shown earlier.

2.

Save this fi le at a convenient location as appUsers.txt.3.

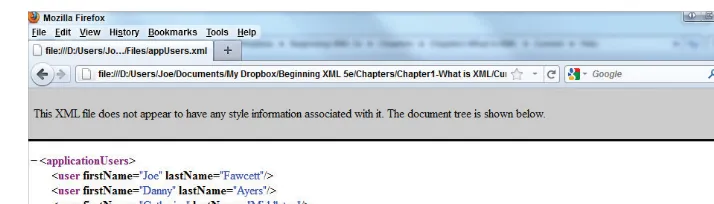

Next, open a browser and paste the path to appUsers.txt into the address bar. You should see something like Figure 1-1. Notice how it’s just a simple list:FIGURE 1-1

4.

Now create another text fi le based on the XML version and save it as appUsers.xml. If you’re doing this in Notepad make sure you put quotes around the full name before saving or otherwise you’ll get an unwanted .txt extension added.WARNING If you are using Internet Explorer for this or other activities, you’ll probably have to go to Tools ➪ Internet Options and choose the Advanced tab. Under the Security section, check the box in front of Allow Active Content to Run in Files on My Computer. This eff ectively allows script to work on local fi les.

As you can see the XML fi le is treated very differently. The browser has shown the metadata in a dif-ferent color than the base data, and also allows expansion and contraction of the applicationUsers section. Even though the browser has no idea that this fi le represents three different users, it knows that some of the content is to be handled differently from other parts and it is a relatively straightfor-ward step to take this to the next level and start to process the fi le in a sensible fashion.

How It Works

Browsers use an XML stylesheet or transformation to display XML fi les. An XML stylesheet is a text-based fi le with an XML format that can transform one format into another. They are most commonly used to convert from a particular XML format to another or from XML to HTML, but they can also be used to process plain text. In this case the original XML is transformed into HTML, which permits the styling of elements to give the different colors as well as the ability to expand and contract sections using script. Transformations are covered in depth in Chapter 8, “XSLT.”

NOTE If you want to view the default style sheet that Firefox uses to display XML, type chrome://global/content/xml/XMLPrettyPrint.xsl into the Firefox address bar. IE has a similar built-in style sheet but it’s not so easily view-able and it’s written in an older, and now no longer used, version of XSLT that Microsoft brought out before the current version was standardized.

NOTE You’ll be using a browser a few times in this chapter to view XML fi les. This has a number of advantages — they're easy, they give reasonable messages if the XML fi le has errors, and you’d be unlikely to fi nd a machine that doesn’t have one. However, for serious development they are not such a good idea, especially if you are trying to convert XML to HTML as you do in the next Try It Out. Because most browsers allow for poorly formed HTML you won’t be able to see if what you’ve produced has errors, and you certainly won’t be able to easily debug if something is wrong. For this reason we suggest you use a proper XML editor when developing. Chapter 2, “Well-Formed XML” covers a number of these.

MORE ADVANTAGES OF XML

One of the aims of XML is to implement a clear separation between data and presentation. This means that the same underlying data can be used in multiple presentation scenarios. It also means that when moving data, across a network for example, bandwidth is not wasted by having to carry redundant information concerned only with the look and feel. This separation is simple with XML as there are no built-in presentational features such as exist in HTML, and is one of its main advantages.

XML Rules

In order to maintain this clear separation, the rules of XML have to be quite strict, but this also works to the user’s advantage. For instance, in the appUsers.xml fi le you saw, values of the users’ fi rst and last names were within quotes; this is a prerequisite for XML fi les; therefore, the following would not be considered XML:

<applicationUsers>

<user firstName=Joe lastName=Fawcett /> <user firstName=Danny lastName=Ayers />

<user firstName=Catherine lastName=Middleton /> </applicationUsers>

The need for quotes in turn makes it easy to tell when certain data is missing, for example here: <applicationUsers>

<user lastName=”Fawcett” /> <user lastName=”Ayers” /> <user lastName=”Middleton” /> </applicationUsers>

causing application errors. Additional ways of validating XML fi les are covered in Part 2 of this book.

Another advantage is the easy extensibility of XML fi les. If you want to add more data, perhaps a middle name for example, to the application users’ data, you can do that easily by creating a new attribute, middleName:

<applicationUsers>

<user firstName=”Joe” middleName=”John” lastName=”Fawcett” /> <user firstName=”Danny” middleName=”John” lastName=”Ayers” />

<user firstName=”Catherine” middleName=”Elizabeth” lastName=”Middleton” /> </applicationUsers>

Consider if you had an application that consumed the original version of the data, with just fi rst name and last name stored in the fi le, and used it to present a list of application users on its main screen. Originally the software was designed to show just the fi rst name and last name of each user but a new requirement demands that the middle name is displayed as well. The newer version of the XML adds the middleName attribute to satisfy this new requirement. Now the older version of the application can still consume this data and simply ignore the middle name information while the new versions can take advantage of it. This is more diffi cult to accomplish if the data is in the type of simple text fi le such as appUsers.txt:

Joe John Fawcett Danny John Ayers

Catherine Elizabeth Middleton

If the extra data is added to the middle column, the existing application will probably misinterpret it, and even if the middle name becomes the third column it’s likely to cause problems parsing the fi le. This occurs because there are no delimiters specifying where the individual data items begin and end, whereas with the XML version it’s easy to separate the different components of a user’s name.

Hierarchical Data Representation

Another area where XML-formatted data fl ourishes over simple text fi les is when representing a hierarchy; for instance a fi lesystem. This scenario needs a root with several folders and fi les; each folder then may have its own subfolders, which can also contain folders and fi les. This can go on indefi nitely. If all you had was a text fi le, you could try something like this, which has a column rep-resenting the path and one to describe whether it’s a folder or a fi le:

Path Type C:\folder

C:\pagefile.sys file C:\Program Files folder

C:\Program Files\desktop.ini file C:\Program Files\Microsoft folder C:\Program Files\Mozilla folder C:\Windows folder

C:\Temp folder C:\Temp\~123.tmp file C:\Temp\~345.tmp file

As you can see, this is not pretty and the information is hard for us humans to read and quickly assimilate. It would be quite diffi cult to write code that interprets this neatly. Comparatively, now look at one possible XML version of the same information:

<folder name=”C:\”>

<folder name=”Program Files”> <folder name=”Microsoft”> </folder>

<folder name=”Mozilla”> </folder>

</folder>

<folder name=”Windows> <folder name=”System32”> </folder>

</folder>

<folder name=”Temp”> <files>

<file name=”~123.tmp”></file> <file name=”~345.tmp”></file> </files>

</folder> <files>

<file name=”pagefile.sys”></file> </files>

</folder>

This hierarchy is much easier to appreciate. There’s less repetition of data and it would be fairly easy to parse.

Interoperability

NOTE Offi ceLibre is an open source application that mimics, to a large extent, other offi ce work applications such as Microsoft Offi ce. It was originally called OpenOffi ce but split off when OpenOffi ce was taken over by Oracle. You can obtain it at www.libreoffi ce.org.

XML IN PRACTICE

Since its fi rst appearance in the mid-’90s the actual XML specifi cation has changed little; the main change being more freedom allowed for content. Some characters that were forbidden from earlier versions are now allowed. However, there have been many changes in how and where XML is used and a proliferation of associated technologies, most with their associated standards. There has also been a massive improvement in the tools available to manage XML in its various guises. This is especially true of the past several years, Five years ago any sort of manipulation of XML data in a browser meant reams of custom JavaScript, and even that often couldn’t cope with the limited sup-port in many browsers. Now many well-written script libraries exist that make sending, receiving, and processing XML a relatively simple process, as well as taking care of the gradually diminishing differences between the major makes of browser. Another recent change has been a more overall consensus of when not to use XML, although plenty of die-hards still offer it as the solution to every problem. Later chapters cover this scenario, as well as others. This section deals with some of the current uses of XML and also gives a foretaste of what is coming in the chapters ahead.

NOTE You can fi nd the latest W3C XML Recommendation at www.w3.org/TR/xml.

NOTE JSON stands for JavaScript Object Notation and is discussed more in Chapters 14 and 16 which relate to web services and Ajax. If you need more information in the meantime, head to www.json.org.