Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:17

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Lowering Business Education Cost With a Custom

Professor-Written Online Text

Lori Jo Baker-Eveleth , Jon Robert Miller & Laura Tucker

To cite this article: Lori Jo Baker-Eveleth , Jon Robert Miller & Laura Tucker (2011) Lowering Business Education Cost With a Custom Professor-Written Online Text, Journal of Education for Business, 86:4, 248-252, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.502911

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.502911

Published online: 21 Apr 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 236

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.502911

Lowering Business Education Cost With a Custom

Professor-Written Online Text

Lori Jo Baker-Eveleth, Jon Robert Miller, and Laura Tucker

University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho, USAInflation-adjusted tuition and fees in education have risen for decades. College textbook costs have risen as well. The authors discuss reasons for higher textbook costs. The development and use of encyclopedic introductory textbooks creates higher monetary cost for students and higher nonmonetary cost for students and teachers, from increased text–course friction. One method to lower costs is the custom, professor-written online textbook. Development issues, such as curriculum coordination, course organization, copyright, institutional cooperation and contractual agreements, pricing, and revenue distribution, are discussed in the business college context. Additionally, student opinion on whether the text was a valuable learning tool is presented and discussed.

Keywords: economics education, electronic, online, textbooks

For the last three decades through 2008, average annual inflation-adjusted tuition and fees at public 4-year colleges increased 2.4%, 4.1%, and 4.2%, respectively (College Board, 2009). Comparable rates of increase at private 4-year institutions were 2.4%, 2.9%, and 4.1%. Textbook costs have risen over time as well, adding to financial pressures on college students and their families. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (2005), between 1987 and 2004 the average price of a college textbook increased twice as fast as the consumer price index, an average of 6% per year. On average, a college textbook costs $125, with many texts not resalable on the used

textbook market. The total textbook cost for a typical year of classes is close to $1,000 (Christopher, 2008; Rampell,

2008).

Indeed, responding to the rising cost of textbooks, stu-dents, parents, state legislatures, federal agencies, university bookstores, and book publishers have made textbook cost an important and controversial issue on college campuses (Anonymous, 2005; Chaker, 2006; Kang, 2004; Kingsbury & Galloway, 2006; Roberts, 2006). A variety of proposals have been offered to address textbook cost, such as us-ing an extensive electronic materials library, free e-books, textbook rentals, and advertising-supported books

(Blumen-Correspondence should be addressed to Lori Jo Baker-Eveleth, Univer-sity of Idaho, Department of Business, 875 Campus Drive, Moscow, ID 83843, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

styk, 2008; Christopher, 2008; King, 2009; Kingsbury & Galloway; Rampell, 2008).

To help understand rising textbook cost, particularly as it relates to economics instruction, it is important to con-sider the context of economics education. The traditional format for economics education is lecture-based, using a text-book as a primary resource, with homework and problem sets (Siegfried et al., 1991; Siegfried, Saunders, Stinar, & Zhang, 1996). Economics textbooks provide finished knowledge in an encyclopedic format reflecting the efforts of economists to understand difficult real-world problems (Siegfried et al., 1991).

In developing a course, instructors must coordinate the text with the course outline. The flow of the course and the flow of the text are often not synchronous. In particu-lar, traditional economics textbooks rarely match the content and organization of an introductory course (Siegfried et al., 1991). Because introductory textbooks become big and en-cyclopedic, they also become more expensive, increasing the monetary cost of higher education. Friction from incomplete coordination of text content with course flow also increases the nonmonetary cost of the text. On the other hand, these types of textbooks can be useful reference books as stu-dents delve deeper into a subject, perhaps in a subsequent course.

Another factor affecting textbook cost stems from sup-plements produced by the textbook publishers. Supsup-plements add features to the text such as DVDs, website resources, and video clips, all bundled with the textbook. These additional

LOWERING EDUCATION COST WITH CUSTOM TEXT 249

resources increase the price of the text, because of the added time and effort required to develop them (Kingsbury & Gal-loway, 2006).

Authors of traditional hard copy textbooks from publish-ers are not able to correct errors or make changes to the text in a timely manner (Larson, 2002). The length of time to cor-rect errors is usually dependent on the publisher for revisions. Therefore, mistakes in a textbook can take 3–4 years to cor-rect. To save money, cost-conscious students may purchase an older edition of a book not realizing errors are present. This is an example of nonmonetary cost incurred with greater text–course friction.

The focus of this study is the use of a custom professor-written online text in an introductory economics course. Stu-dents at a residential-based, medium-sized, 4-year university had access to the online text at the course website but could download the complete text and print if desired. We suggest that this textbook method reduces monetary textbook cost to students, reduces nonmonetary cost from text-course fric-tion, and allows for error correction and other revisions to be addressed quickly.

In the next section we discuss the literature about the ef-ficacy of substituting an online text for a standard hard copy text from a publisher. Next, issues associated with univer-sity policy, textbook development, and implementation in a specific economics course are described. Student opinion on whether the online text was a valuable learning tool is also provided. Finally, we offer some concluding comments and suggestions for future research.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The textbook serves an important purpose in the classroom particularly when average class sizes are over 60 students. A challenge in large classes is the ability of the instructor to an-swer students’ questions (Sweeney, Siegfried, Raymond, & Wilkinson, 1983). Due to the ratio of one faculty member to many students, often students need to acquire additional con-tent and clarification outside of the classroom from sources such as textbooks. With a variety of content access methods available—traditional hard copy textbooks, electronic text-books, Web-based materials, and Web-search engines—there are additional opportunities to reach students outside of the classroom and increase the understanding of and engage-ment with class material (Johnson & Harroff, 2006; Rampell, 2008). Different learning styles also suggest that providing different ways of accessing classroom content is advanta-geous for learning (Dorn, 2007; Huon, Spehar, Adam, & Rifkin, 2007).

Moving toward electronic access of content allows mate-rial to be updated or corrected more frequently than waiting for a new edition from the publisher. An issue with traditional texts is that by the time the material is published, it is out of date (Stewart, 2009). This is especially problematic in some

dynamic fields, such as information systems or technology, where the rate of change in material is very rapid.

Providers of electronic content access are experimenting with different, lower-cost text pricing models. Some are free, whereas others have a quarterly or semester fee, or request a donation to a cause/program (Beezer, 2009; Rampell, 2008; Stewart, 2009). A new digital publisher, Flat World Knowl-edge, is providing interactive, electronic material as well as a nondownloadable version free of charge. The University of Phoenix consolidated all course textbooks in an electronic library, charging$75 a semester for electronic access to any

textbook (Blumenstyk, 2008). Open-source programs, such as GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL), allow the au-thors of the content as well as readers to make suggestions and note errors and corrections (Beezer, 2009).

In spite of advantages in terms of cost, timeliness of cor-rections and changes, and multiple methods of displaying content, the shift to electronic material has been slow. The lack of comfort reading from the computer has slowed the acceptance of electronic textbooks (Carlson, 2005; Nelson, 2008). Eye strain from a computer screen and back and neck problems are a concern (Crawford, 2006). Although new electronic readers such as Amazon’s Kindle have improved the ability to read electronic textbooks, students were trained to use traditional textbooks (Carlson). Many students want to be able to pick up the textbook as needed, as opposed to being tethered to a computer.

Resistance to electronic texts might be waning, however. The rising cost of tuition and the present economic downturn may likely have an effect on colleges and universities in the future (Debolt, 2008). An increase in tuition may influence students when they purchase their textbooks. Cech (2008) suggested that students facing rising costs may soon be will-ing to switch methods. Computer ownership, the Internet, social networking, and short text messaging have become ubiquitous for most present college students (Ellison, Stein-field, & Lampe, 2007). Their acceptance of various commu-nication devices and technology creates the possible impetus for change in college textbooks.

Changing the mechanism for reading textbooks (to elec-tronic) allows an environment in which students can interact and engage with the material in a different way. Most digital books are searchable, can be highlighted just as a traditional textbook, and often have a comment box or annotation ability on the pages (Ravid, Kalman, & Rafaeli, 2008). Many tech-nologies being used in education can be used to enhance stu-dents’ ability to interact and collaborate with other students as well as the professor (Contreras-Castillo, Favela, Perez-Fragoso, & Santamaria-del-Angel, 2004; Hall & Graham, 2004; Paxhia, 2008). Augmenting the learning experience by using technologies, such as Web 2.0 tools (e.g., blogs or wikis), shift content development away from the publishers and instead to faculty, instructors and students (Ravid et al.). Web 2.0 tools allow users to interact online by sharing pic-tures, videos, opinions, and general social networking. Blogs

are the equivalent to a paper-based diary, whereas a wiki al-lows anyone with permissions to edit descriptions of events much like an encyclopedia (Alexander, 2006).

Electronic content is often easier to find in an online envi-ronment (e.g., Blackboard or Moodle) in which students can link to the material. Discussion of the material, particularly if the content is controversial or debatable, engages students more in the material (Conole, Dyke, Oliver, & Seale, 2004; Soekijad, Huis in ‘t Veld, & Enserink, 2004; Zaitseva & Bule, 2006). Orrill (2000) classified these types of interactions as learning objects in which knowledge is coconstructed by those interacting with the material based on authentic prob-lems and issues, increasing the motivation to learn. Learning objects are advantageous because of the portability to other learning environments (Koper & Manderveld, 2004). One-time use objects, such as standard hard-copy textbooks, are limited in portability.

POLICY ISSUES

With a desire to increase the use of technology in the class-room, the college administration recommended writing an online text for a four-credit introductory economics course. The idea stemmed partly from a desire to improve the course through use of information technology, but also it came from a rational economic response to budget pressures in pub-lic higher education. Universities, colleges, and academic units, especially business schools, are striving to become state-assisted rather than state-supported. Service units, such as the teaching innovation center, which was a partner in this effort, also faced pressures to become self-supporting. Although custom, professor-written online texts have the po-tential to lower the cost of education to students, they also can transfer remuneration from book publishers to faculty and other on-campus units. Next, we discuss the develop-ment of the economics text.

Textbook Development

The economics text was designed for a unique course in a unique curriculum, an integrated business curriculum (Pharr, Morris, Stover, Byers, & Reyes, 1998; Stover, Morris, Pharr, Reyes, & Byers, 1997). In conjunction with the development of the integrated business curriculum, the college adjusted and aligned introductory feeder courses in economics and accounting. By eliminating duplication and transferring some material, a traditional two-course, 6-credit macroeconomics and microeconomics sequence was turned into one 4-credit course. The online text was written for this course.

Before proceeding to writing the text and obtaining insti-tutional permission to charge a course fee for it, students were questioned about the idea of an online text for the course. To obtain a general sense of the demand for the online text, a short anonymous questionnaire was given to the spring 2005

class. The response rate was nearly 100%. In all cases, the voluntary nature of the response, anonymity, and confiden-tiality were offered and enforced. A majority of students agreed or strongly agreed that the existing hard-copy text from a publisher was a valuable learning tool and a similar number thought that a cheaper online text was a good idea.

Implementation

Writing of the text took about a year to complete by a sin-gle professor–author. College administration provided funds for a research assistant to create electronic versions of the graphs and other figures in the text. The text writing was done primarily as an expansion and verbal elaboration of class notes and presentations accumulated through years of teaching introductory economics material. Completion of the initial custom text was shorter than a traditional text from a publisher, because the author was also publisher, editor, and reviewer. Resources were not available for external comment and editorial assistance at the time.

Proposed student course fees are reviewed by a faculty committee. Approval from this committee to offer the text for a course fee is not easily received. Committee members are often sympathetic to the economic and financial condi-tion of students, but would prefer professors develop custom materials and give it to the students at no charge. For this rea-son, the cost-saving nature of the online text was emphasized in the proposal to the committee and approval was received. The price for the text was$51. This number was derived

by reviewing used and new introductory textbooks. It was determined that half the average price of a used book for this and other introductory economics courses would be a rea-sonable amount. Electronic versions of common economic texts from major publishers sold in the university bookstore for 52% of the new hard-copy price, on average. A resource on campus for faculty, a teaching center, created an eas-ily accessible electronic copy of the text in which students could read or download the material. The center maintained and managed the technical infrastructure necessary to sup-port the online text. The university’s legal personnel devel-oped a memorandum of understanding (MOU) about issues such as copyright, distribution of revenue, length of commit-ment, and other rights and responsibilities of the college, as well as the author’s department, the teaching center, and the professor–author.

In the MOU, the author authorized registration of copy-right in the name of the university. The university granted the author unlimited, nonexclusive, nontransferable license to use material in the online text, as long as it did not compete with the purpose of the text in the course. The agreement was for three years, and the university agreed to negotiate in good faith with the author for another six years after the initial three-year agreement.

Revenue distribution for the 3-year period was 60% to the author and 40% to the teaching center. Neither the college

LOWERING EDUCATION COST WITH CUSTOM TEXT 251

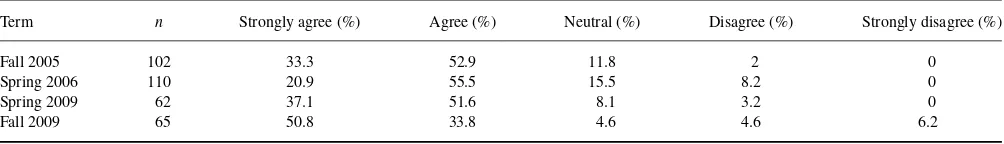

TABLE 1

Student Opinion Regarding the Statement: “The Online Text Was a Valuable Learning Tool”

Term n Strongly agree (%) Agree (%) Neutral (%) Disagree (%) Strongly disagree (%)

Fall 2005 102 33.3 52.9 11.8 2 0

Spring 2006 110 20.9 55.5 15.5 8.2 0

Spring 2009 62 37.1 51.6 8.1 3.2 0

Fall 2009 65 50.8 33.8 4.6 4.6 6.2

nor the university received a share, although the university levies a tax of 6% on revenue of this nature. Following the initial 3-year period, the revenue distribution was amended to 90% to the author and 10% to the teaching center. The center, concerned about covering initial development costs, recognized that steady-state maintenance costs were much lower.

DISCUSSION

Several outcomes were desired by the development of a cus-tom, online economics textbook: first, reducing the cost of textbooks to students; second, linking the course material to the flow of the textbook; and third, having a textbook that is more accurate with frequent updates and the inclusion of present events.

Faculty can’t control how much students use textbooks, but faculty can contribute to students’ ability to obtain the book by reducing costs. In this context, having the professor develop the textbook and deliver it in an online format pro-vided a cost effective way for students to get access to the textbook.

An important aspect to consider in online textbooks is usability and readability. Lowering the cost of a textbook through online methods might be considered questionable if the usability of the text is compromised in the process. In fact, the literature suggests that this may be the case (e.g., Balas, 2006; Carlson, 2005; Crawford, 2006; Johnson & Har-roff, 2006). If students have trouble using the new text, or if it lacks necessary content to succeed in the course, students would complain and probably not recommend the course or textbook to future students. In four semesters over the 5-year life of this textbook, students were queried about the useful-ness of the textbook for the course. A voluntary and anony-mous short survey was provided to students each semester (as approved by the institutional review board at the institu-tion). These results appear in Table 1. From the students in the course, the online textbook appears to have been useful. From a low of 76.4% in the spring 2006 semester to a high of 84.6% in fall 2009, a very high proportion of the students either agreed or strongly agreed with a statement that said the text was a valuable learning tool. In the fall semester 2009, “Strongly Agree” was the modal response at nearly 51%. An inference can be made that the online textbook was usable and readable and thus made it a valuable learning tool.

The final issue in using an online textbook is the speed at which a text can be updated and changed. Updating of the online textbook to include present events and corrections was relatively easy for the professor and appeared seamless to students. With the help of the teaching center, the au-thor could add additional pages and have the center make it available within a few days. For example, the present financial–economic crisis was important to discuss in class and clarify misconceptions. This allowed present graphs, ta-bles, and descriptions to be included in the textbook without the students relying on unreliable and questionable sources on the Internet.

Although many of the desired outcomes were realized from the development and implementation of an online text-book, there are limitations and additional research that need further exploration. We address some of these in the next section.

CONCLUSION

Interpretation of the discussed results should be considered with regard to the limitations. Three different limitations are addressed in this article—the specific context for the use of the text, use of student opinions, and professor–author agreements.

First, the type of online text development, a bottom-up process, was specific to the institution, curriculum, course, and the professor. The delivery of an integrated business curriculum required a unique textbook to address the needs of students. In a different context or in a more traditional introductory economics course, a traditional textbook may meet the needs just as well.

The second limitation was the use of student opinions. We cannot disentangle opinion about the content of the text and its ease of use or its lower cost, among other charac-teristics. Students may have overlooked shortcomings of the online text because of its cost advantage. Furthermore, at this time conclusions about the quality of the text have not been assessed except by student opinions. Additional research is presently underway to understand the effectiveness of elec-tronic books at this university.

Finally, the custom text was developed by the professor teaching the course. The process described here compensates the professor–author and other university entities involved in development and delivery of the text through the imposition

of a mandatory course fee. If this option for texts is to be viable, professors may likely need some monetary incentive to engage in this activity. The imposition of a course fee for the custom, professor-written online text is crucial for faculty to develop a textbook. Reluctance by many to a direct flow of resources from students to professors exists. Exploration of this and other issues of textbook finance are beyond the purpose of this paper, but such exploration is certainly worthy of future consideration.

REFERENCES

Alexander, B. (2006). Web 2.0: A new wave of innovation for teaching and learning.EduCause Review, 41(2), 32–44.

Anonymous. (2005, September 6). High book prices reason to rebel.

Spokesman Review, B4.

Balas, J. L. (2006). Are e-books finally poised to succeed?Computers in Libraries, 26(10), 34–36.

Beezer, R. (2009). The truly free textbook.EduCause Review, 44(1), 23–24. Blumenstyk, G. (2008, June 13). To cut costs, ought colleges look to

for-profit models?Chronicle of Higher Education, 54(40), A19–20. Carlson, S. (2005, February 11). Online textbooks fail to make the grade.

Chronicle of Higher Education, A35–36.

Cech, S. J. (2008, July 30). Textbooks moving into cyberspace.Education Week, 27(44), 6.

Chaker, A. M. (2006, September 28). Efforts mount to cut costs of textbooks: As prices rise at twice the rate of inflation, states pass laws to encourage cheaper alternatives.The Wall Street Journal, D1–3.

Christopher, L. C. (2009).Academic publishing: Digital alternatives to ex-pensive textbooks. Retrieved from http://www.seyboldreport.com/book-publishing / academic - http://www.seyboldreport.com/book-publishing - digital - alternatives - expensive - text books

College Board. (2009). Trends in college pricing 2009. Retreived from http://www.trends-collegeboard.com/college pricing/

Conole, G., Dyke, M., Oliver, M., & Seale, J. (2004). Mapping pedagogy and tools for effective learning design.Computers & Education, 43(1–2), 17–33.

Contreras-Castillo, J., Favela, J., Perez-Fragoso, C., & Santamaria-del-Angel, E. (2004). Informal interactions and their implications for online courses.Computers & Education, 42, 149–168.

Crawford, W. (2006). Why aren’t ebooks more successful?EContent, 29(8), 44.

Debolt, D. (2008). Tuition at american colleges rose moderately.Chronicle of Higher Education, 55(8), A26.

Dorn, R. I. (2007). Online versus hardcopy textbooks.Science, 315, 1220. Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of facebook

“friends”: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites.Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12, 1143–1168. Hall, H., & Graham, D. (2004). Creation and recreation: Motivating

collabo-ration to generate knowledge capital in online communities.International Journal of Information Management, 24, 235–246.

Huon, G., Spehar, B., Adam, P., & Rifkin, W. (2007). Resource use and academic performance among first year psychology students.Higher Ed-ucation, 53(1), 1–27.

Johnson, C., & Harroff, W. (2006). The new art of making books.Library Journal, 131(11), 8–12.

Kang, S. (2004, August 24). New options for cheaper textbooks: Under fire for high prices, publishers push alternatives; renting your chem book.The Wall Street Journal, D1.

King, P. (2009, April 23). A textbook case of renting books.The Wall Street Journal, B12.

Kingsbury, A., & Galloway, L. (2006, October 8). Textbooks en-ter the digital era. U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved from http://www.usnews.com/usnews/edu/articles/061008/16books.htm Koper, R., & Manderveld, J. (2004). Educational modelling language

and learning design: New opportunities for instructional reusability and personalised learning.British Journal of Educational Technology, 35, 537–551.

Larson, R. (2002, April 9).E-enabled textbooks: Lower cost, higher func-tionality. Retrieved from http://campustechnology.com/articles/39043/ Nelson, M. R. (2008). Is higher education ready to switch to digital course

materials?Chronicle of Higher Education, 55(14), A29.

Orrill, C. H. (2000).Learning objects to support inquiry-based online learn-ing. Retreived from http://reusability.org/read/chapters/orrill.doc Paxhia, S. (2008, September).Interactive content: Bringing students and

professors together. Paper presented at the Multimedia Educational Resource for Learning and Online Teaching (MERLOT) Confer-ence, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Retrieved from http://ida.lib.uidaho. edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true &db=aph&AN=34623812&site=ehost-live

Pharr, S. W., Morris, J. S., Stover, D., Byers, C. R., & Reyes, M. G. (1998). The execution and evaluation of an integrated business common core curriculum.Journal of General Education, 47, 166–182.

Rampell, C. (2008, May 2). Free textbooks: An online company tries a con-troversial publishing model.Chronicle of Higher Education, 54(34), A14– 15.

Ravid, G., Kalman, Y. M., & Rafaeli, S. (2008). Wikibooks in higher educa-tion: Empowerment through online distributed collaboration.Computers in Human Behavior, 24, 1913–1928.

Roberts, S. (2006, April 25). Costly textbooks draw scrutiny of lawmakers.

The Wall Street Journal, D2.

Siegfried, J. J., Bartlett, R. L., Hansen, W. L., Kelley, A. C., Mc-Closkey, D. N., & Tietenberg, T. H. (1991). The status and prospects of the economics major.The Journal of Economic Education, 22, 197– 224.

Siegfried, J. J., Saunders, P., Stinar, E., & Zhang, H. (1996). Teaching tools: How is introductory economics taught in america?Economic Inquiry, 34, 182–192.

Soekijad, M., Huis in ‘t Veld, M.A.A., & Enserink, B. (2004). Learning and knowledge processes in inter-organizational communities of practice.

Knowledge and Process Management, 11(1), 3–12.

Stewart, R. (2009). Some thought on free textbooks.EduCause Review, 44(1), 24–26.

Stover, D., Morris, J. S., Pharr, S., Reyes, M. G., & Byers, C. R. (1997). Breaking down the silos: Attaining an integrated business common core.

American Business Review, 15(2), 1–11.

Sweeney, M. J., Siegfried, J. J., Raymond, J. E., & Wilkinson, J. T. (1983). The structure of the introductory economics course in United States col-leges.The Journal of Economic Education, 14(4), 68–75.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2005).College textbooks: En-hanced offerings appear to drive recent price increases. Gao-05-806. Washington, DC: Author.

Zaitseva, L., & Bule, J. (2006, September). Electronic textbook and e-learning systems in teaching process. Proceedings of 2006 E-Learning Conference on Computer Science Education, Coimbra, Portugal.