Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 23:48

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

An International Internet Research

Assignment—Assessment of Value Added

C Scott Greene & Robert Zimmer

To cite this article: C Scott Greene & Robert Zimmer (2003) An International Internet Research Assignment—Assessment of Value Added, Journal of Education for Business, 78:3, 158-163, DOI: 10.1080/08832320309599714

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320309599714

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 9

View related articles

An International Internet Research

Assignment-Assessment

of

Value Added

C.

SCOTT GREENE

ROBERT ZIMMER

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

California

State University, Fullerton Fullerton, Californiauring the past decade, the glob-

D

alization of markets has been accelerating rapidly. Forces driving this global expansion include the pro- liferation of companies conducting business on the Internet and World Wide Web, the opening up of previous- ly closed or restricted regions, the growth of free-trade agreements, the fall of communism, and improvedpolitical stability (Abboushi, Lackman,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Peace, 1999).

In light of this dramatically chang- ing landscape, business students will need to possess a global perspective and a facility for conducting business over the Internet (Atwong & Hugstad, 1997; Holmes & Clizbe, 1997). In 1994, the American Assembly of Col- legiate Schools of Business (AACSB) required that undergraduate and gradu- ate curricula include “global issues’’ and “global economic environments” as part of an internationalized context for business (Fugate & Jefferson, 2001). Recently, the AACSB revised its curriculum standards to include “ethical and global issues, demograph- ic diversity and the influence of politi- cal, social, legal and regulatory, envi- ronmental and technological issues

. . .

”(AACSB, 2000).

In this article, we review various ap- proaches for internationalizing business school cumcula, introduce a global Inter-

ABSTRACT. In light of the recent emphasis on accountability, globaliza- tion, and technology skills in business education, in this study the authors investigated the effects of a two-part global Internet research project on stu- dent learning. They found that stu- dents improved significantly in seven business skills and interests, including increased proficiency with foreign market research based on electronic information sources and improved knowledge of doing business in a for- eign market. Also, student understand- ing of international segmentation and targeting based on country or regional parameters was enhanced. Measures of project sophistication and general satisfaction yielded highly encourag- ing findings. Most students reported increased interest in further study of, or a possible career in, international business.

net research assignment for

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

an introduc-tory business course, and present find- ings from a student survey investigating the assignment’s value in providing stu-

dents with

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

a global perspective and im-proving their international Internet re- search skills.

Approaches to Internationalizing Business School Curricula

To incorporate a strong international dimension into business school curric- ula, schools and their faculty members are using various approaches, each

requiring different levels of commit- ment. The infusion approach involves adding international components across required courses. Manuel, Shooshtari, Fleming, & Wallwork (2001) found that 67% of respondent undergraduate schools and 62% of

graduate schools included international topics as a chapter or component in business courses. These findings are comparable with previous research confirming the popularity of the infu- sion method (Arpan, Folks, & Kwok, 1993; Fleming, Shooshtari, & Wall- work, 1993).

A second approach entails tailoring academic programs through the creation of specialized coursework in interna- tional business. While updating their 1993 survey of AACSB member schools, Manuel et al. (2001) found that approximately three fourths of those schools offered elective international business courses at the undergraduate and graduate levels. To help students achieve the higher levels of “global understanding” and “global compe- tence” endorsed by Kedia and Cornwell (1994), business schools increasingly have been involving students in exchange programs, foreign study tours, international internships, and study abroad programs. This has been labeled the immersion approach (Fugate & Jef- ferson, 2001).

158

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of Education for BusinessInternationalizing the Introductory Marketing Course Through Global

Internet Assignments

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

In the past few years, researchers’ attention has been directed at interna- tionalizing the introductory marketing

course (Lamont

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Friedman, 1997;Johnson & Mader, 1992). One study focused on examining the extent of classroom coverage and the teaching materials used by instructors to cover international topics in the introductory marketing course (Zimmer, Bruce, &

Lange, 1996). It appears that marketing instructors are sensitive to the need for

placing greater emphasis on more rigor-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ous teaching of international marketing. In a survey of over 400 marketing educa- tors, Jarboe, McDaniel, and Lamb (1989) found that classroom coverage of interna- tional marketing averaged 1.54 hours; it would have been increased to 3.72 hours (a gain of 142.3%) if student contact hours were doubled from 45 to 90. These intentions are consistent with the findings of the more recent survey by Manuel, Shooshtari, Fleming, and Wallwork (2001), who projected that the percentage of class time used to cover international topics will increase from 12% to 18% in

undergraduate courses in the next

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 years.Business educators have begun em- bracing the Internet as an invaluable tool for internationalizing the cunicu- lum. Siegel (1996) reported having stu- dents in an international marketing course complete a “country book” as- signment solely on the Internet. At- wong, Lange, Do&, and Aijo (1996) had international marketing students conduct a similar research project, and then grouped them into crossnational teams with foreign students of their tar- geted countries. They were required to collaborate and communicate with their teammates by using available technolo- gy. Lawson, White, and Dimitriadis (1998) had students in international business and marketing courses com- plete three global research projects demanding various levels of technical sophistication and intercultural interac- tion. In the first project, students were required to make extensive use of the National Trade Data Bank (NTDB) to research an assigned country via either the Internet or a CD-ROM. Students

rated this assignment as highly benefi- cial in increasing their awareness of government resources, their familiarity with the NTDB, and their understand- ing of the global environment.

Because of the increasing number of nontraditional students (older and/or working full time) for whom study time is scarce, Smart, Kelley, and Conant (1999) recommended assigning four or five rigorous but easily manageable pro- jects instead of one lengthy term paper. Previous research has focused on using and assessing global Internet projects in international marketing and internation- al business courses. In this study, we dis- cuss an introductory marketing course that incorporated a small, easy-to-man- age international Internet assignment.

A Global Internet Research Assignment

for

the Introductory Marketing CourseThe assignment for the introductory marketing course involves having stu- dents scan the globe to select a country in which they would like to work for part of their professional career or to start their own business. The assign- ment is introduced between the topics of international marketing and market segmentationkargeting. Students form into small groups to discuss different bases or variables that they could employ for carving up and reconfigur- ing the “world market.” From these 15- minute interactions, segmentation bases such as geography (continent, country, region), religion, language, economic structure, and political sys- tem are discovered. Then we solicit specific examples of using those possi- ble bases for grouping countries into potential markets. Traveling from the conceptual to the applied, students pre- pare for serious consideration of their targeted countries, which they must use the Internet to research. This assign- ment provides an effective means of internationalizing the introductory marketing course, while answering marketing educators’ call for the inclu- sion of Internet-based assignments for accessing and retrieving global market information (Atwong & Hugstad, 1997; Lamont & Friedman, 1997; Siegel, 1996).

The four primary student learning objectives of this assignment are to

1. upgrade students’ global research and information retrieval skills through use of the Internet;

2. encourage students to study and to learn about the demography, culture, economy, political system, and geogra- phy of a foreign country and its poten- tial for postcollege employmentlentre- preneurship opportunities;

3. have students apply the concepts of

market segmentation and targeting in developing a global personal marketing

campaign; and

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

4.

upgrade students’ report-writing skills.Both business educators and business students perceive the need to upgrade students’ global research and informa- tion retrieval skills continuously. Miller and Mangold (1996) asked students to assess the importance of various on-line information-gathering skills for a busi- ness professional and to rate their own skills at collecting information from each source. Respondents rated “gather- ing information from the Internet” as one of the three most important skills, but they rated their own skill level as lowest on it. Overall, they rated their competency with technology-based sources of information as barely accept- able. According to Natesan and Smith (1998, p. 151) “providing the global marketing student with Internet-based data-acquisition skills to gather compet- itive intelligence becomes essential.”

In addition to technical information literacy, business students should have both reflective and professional informa- tion literacy. Reflective information lit- eracy entails students’ ability to evaluate critically the sources and contents of information through the use of relevant criteria. Specifically, it involves making informal decisions about whether and how to use information through assess- ment of the credibility of sources and currency of data. Professional informa- tion literacy consists of the ability to understand and apply the language and specialized concepts of a profession from a practitioner’s perspective (Stern- gold & Hurlbert, 1998). We address this type of literacy by helping students

learn to write about practical marketing

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

January/February

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2003 159issues through assignments such as individual research projects on foreign countries. A sound body of research supports this type of active learning to develop students’ competencies and

skills (Adrian

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Palmer, 1999; Wright,Bitner, & Zeithaml, 1994). Marketing educators seem to have adopted written reports and cases involving country analyses as the most widely used tools for developing student skills in the glob- al marketing classroom (Lamb, Shipp,

& Moncrief, 1995).

In Table 1, we show the points that students must research in the first writ- ten part of the global Internet research assignment. The first part consists of a two-page form that can be used for recording the information; it can be adapted to fit students’ needs and must be completed individually by each stu- dent. The required country information involves seven categories: demographic, economic/political/geographic, cultural norms/values/business etiquette, busi- ness/employment barriers, lifestyle con- siderations, largest industries and com- panies, and largest exports and imports. Students need to use several sources, because no one site provides them with sufficient information to complete this part of the assignment.

The assignment’s second part asks stu- dents to answer the following six ques- tions regarding their target countries:

1. How did you decide on this coun-

2. What are its most attractive fea- tures that drew you to it and why?

(lifestyle, culture, the people, etc.)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

3. What are the major threats and

opportunities for conducting business in this country?

4. If you were to work in this country, in which region or city would you like

to live and why?

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5. What new insights have you gained about this country from your research?

6. Was this a worthwhile assignment

for you? Why or why not?

Each student writes a two- to three-page typed report, with a cover page. We encourage them to create computer graphic visuals of their targeted coun- tries. Students have 3 weeks to complete both parts of the assignment. Graduate

students then grade the projects, which

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

160

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

try?

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of Education for Business

TABLE 1. First Written Part of the Global Internet Research Assignment

Assignment: Researching a Foreign Country’s Potential Name

Class time Targeted country Demographic

Population size

Rate of population growth

Age structure and composition of population Income distribution

Median household income Educational levels

GNP

Rate of growth of

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

GNPPolitical climate (government) Physical size of country Five largest industries ($US.) Five largest companies ($U.S.)

Five largest exports ($U.S.) Five largest imports ($US.)

Cultural norms, values, and business etiquette

Business/employment barriers (legal, political, cultural) Lifestyle considerations

Economic, political, and geographic data

Cost of living

Housing costdrental rates

Climate conditions Crime rate

constitute between 5% and 10% of each student’s final grade.

Assessment Method

The majority of students have accom- plished very good to excellent work on this assignment, as assessed by faculty members who have used it in their classes. Additionally, anecdotal evi- dence from students suggests that the assignment successfully accomplishes several learning goals. To gain a quanti- tative and more formal assessment of the assignment’s value, we designed a written questionnaire, pretested it, and administered it to students who had recently completed the assignment.

Colleagues expanded the initial 12-

item questionnaire to 22 questions. The expanded version, which was pretested for clarity and internal validity among a convenience sample of students, requires about 7 minutes to complete. We made necessary revisions based on the pretest. For consistency, all possible questions employed 10-point bipolar or semantic differential scales. These self-assess- ment measures essentially estimated the assignment’s value-added in seven areas.

Additionally, the instrument determined five areas of perceived complexity or sophistication and general satisfaction with the assignment, as well as personal characteristics of the students.

Specifically, the value-added items

measured degree of increase in the fol- lowing areas:

1. familiarity with electronic informa- tion sources

2. familiarity with foreign market

research through use of electronic infor- mation sources

3. awareness of the amount of valuable

information on a targeted country avail- able through electronic information sources

4. awareness of situational facts about a targeted country

5 . understanding of application of the concepts of segmentation and targeting to the global marketplace

6 . knowledge of how to do business (at

an elementary level) in a foreign market 7. interest in further study of, or a career in, international business

Furthermore, for credibility purposes regarding item 2 (above), another ques- tion measured increase of electronic

information research skills on foreign

markets (Churchill,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1999, p. 408).The five areas of perceived complexity or sophistication and general satisfac- tion specifically measured the following factors:

1. diversity of information sources

2. hours spent on the assignment

3. search hours invested on the Inter- net

4. number of different Interneweb

sites visited

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 . degree of general satisfaction with the assignment

The following five specific

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

personalcharacteristics were identified:

1. location of the personal comput- er(s) used to access the Internet

2. number of international Internet

searches performed in the last year before this assignment

3. major area(s) of emphasis in uni- versity studies

4. gender

5. number of years of U.S. residency

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Results

Immediately after completing the assignment, 143 upper division under-

graduate students (mostly business majors) in four different principles of marketing classes at a major state univer- sity answered the anonymous question- naire. Graduate students administered the questionnaire during classtime. Analyses of the data collected from those questionnaires indicate highly encourag- ing findings about the value-added from the assignment (see Table 2).

Examination of the data first revealed that the students already possessed a fairly strong familiarity with electronic information sources before they com- pleted the assignment-they had a mean familiarity of 6.25 on a 10-point scale.

However, when conducting foreign mar- ket research using electronic informa- tion sources, students reported a mean of only 4.37. The data in Table 2 show that,

after the assignment, technology-assist- ed foreign market research familiarity rose to a mean of 7.25, nearly a three-

point improvement. In addition, students reporting high levels of foreign market research familiarity jumped from 13%

before the assignment to 46% after

assignment completion. Assessing im- provement in students’ proficiency with foreign market research using electronic information sources appears critical in light of industry’s calls and the AACSB’s mandate that business stu- dents develop a global perspective with the ability to conduct business using technology.

To corroborate those improvement results, we asked students a parallel question: “To what extent did this assignment help to increase your elec- tronic information research skills on for- eign markets?’ On a 10-point scale

ranging from 1 (not at all helpful) to 10

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(extremely helpful), students rated the assignment’s helpfulness at a level of

7.22 and gave it a modal value of 8, with 34.3% of students reporting that value.

On a 10-point scale ranging from 1

(much less than expected) to 10 (much

more than expected), 72.8% of the stu-

dents responded that they found more valuable information on their targeted countries than they had expected, with a mean response of 6.68.

Other value-added items revealed meaningful improvements in students’ skills. The data in Table 2 demonstrate

clear improvement in student under- standing of market segmentation and targeting: The mean for this skill in- creased by 1.94 points. Also, students’

knowledge of doing business in their targeted country had the largest increase, by over 3 points on average.

For entrepreneurial students desiring to go into an international business for themselves, such as importing or ex-

porting, a practical understanding of segmentation and targeting of foreign markets is crucial. Furthermore, compa- nies planning to become global certain- ly desire employees possessing such skills and knowledge on developing new foreign markets.

The last of the value-added items measured increased interest in further study of, or a possible career in, interna- tional business. On a scale ranging from 1 (not at all increased) to 10 (extremely

increased), we found a notable mean increase of 5.3 1 in student interest in the

global arena.

We can gain greater insight into stu- dents’ increased interest in the global arena by examining its correlates. Their increased interest had a weak but statis- tically significant (at the .05 level) Pear- son correlation coefficient of .17 with students’ increased skill in researching foreign markets. A slightly more posi- tive correlation, with a -22 coefficient

significant at the .01 level, occurred between students’ increased interest in international business and the number of international Internet searches that they performed during the last year before this assignment. Those results imply that more international Internet searches pos- itively relate to increased interest in the global arena. An even stronger correla- tion coefficient of .27, significant at the .01 level, emerged between students’

increased interest and their increased awareness of a country’s situational facts. The strongest correlation (.36 sig-

nificant at the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

.01 level) was betweenstudents’ increased interest and how sat- isfied they felt about completing the

TABLE 2. Value-Added Skills and Knowledge Gained by Respondent Stu- dents From Assignment

Students’ skills and knowledge

Familiarity with general electronic

Familiarity with foreign market

Understanding segmentation and

Knowledge of doing business in information sources

research

targeting of markets

targeted country

Before After

assignment assignment Difference

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(M) (M) (after - before)

6.25 8.07 1.82

4.37 7.25 2.88

5.16 7.10 1.94

4.21 7.31 3.10

January/February 2003 161

assignment. The .36 correlation coeffi- cient, significant at the .01, level, demonstrates that the more interested in the global marketplace that students became as a result of completing the assignment, the more satisfied they were with the assignment, and vice versa.

Results for all of the value-added items demonstrated convincing improve- ment in student skills resulting from the international Internet assignment. Our next assessment focused on student per-

ceptions of the assignment itself.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Perceived Complexity and Satisfaction

To gauge students’ feelings about the assignment, we explored five areas of complexity/sophistication and general satisfaction on the questionnaire. We asked students what their sources were for the information used to complete the assignment. After recoding responses for each source as 0.0 if not used and

1.0 if used, we found that 33.8

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

% of thestudents used Lexis-Nexis, 95.8% used the Internet, 62.7% used printed library references, and 30.1% used “other” sources (e.g., books, encyclopedia, and newspapers). Students reported a mean of 2.25 sources consulted.

We also investigated the number of hours that students spent on the entire assignment and on searching the Inter- net. Students invested a mean of 6.8 hours, with 19.7% of students spending 2 to 4 hours on the assignment, 40.9% spending 5 to 7 hours, and 38.7%

investing

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

8 to 10 or more hours.In searching the Internet for informa- tion, students reported a mean of 5.2 hours. Forty-eight percent of the stu- dents invested 2 through 4 hours on the Internet, 25.9% spent 5 through 7 hours, and 23.8% invested 8 through 10 or

more hours. Like the results regarding hours spent on the overall assignment, these results indicate a substantial yet reasonable amount of study time devot- ed to developing international Internet research skills.

The questionnaire additionally probed the number of different Web/ Internet sites (not pages or “branch- es”-e.g., cwww.cia.gov>) that the stu- dents visited for their international Internet search. Students went to a mean number of 10.0 different sites, with

39.2% visiting

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1 to 5 sites, 35.7% goingto 6 through 10 sites, and 23.1% visiting 11 or more different Web sites. We took into account student effort expended and gains from the assignment to mea- sure students’ satisfaction with it on a scale ranging from 1 (extremely dissat-

isfied) to 10 (extremely satisfied). They reported a moderately positive 6.9 mean level of satisfaction. With almost 45% very satisfied and over 80% of students at least somewhat satisfied with the time spent and their gains from the assign- ment, most students felt content about their return on effort.

It appears that students who expend- ed a greater effort on the assignment experienced roughly the same level of contentment with their investment as those who expended less effort. A corre- lation coefficient of .33 between stu- dents’ increased awareness of situation- al facts about their targeted country and their satisfaction demonstrates that improvements in their understanding of a foreign market related significantly with their satisfaction resulting from completing the assignment.

Students’ Personal Characteristics

Finally, we investigated student back- grounds and their access to technology. We asked students to mark all electron- ic sources that they accessed for infor- mation on their targeted countries. Just over 83% used personal computers in their homes, 79.6% used them in the university library, 9.2% used personal computers at work, and only 5.1 % used them at other locations (friends’ homes or university computer labs). Apparent- ly most students found it convenient to perform part of their search at home and another part at the university library.

Another question asked students the number of international Internet search- es that they performed in the year before the assignment. Slightly more than 44% of students did no searches in the prior year, 29.4% performed one or two searches, and 26.6% had done three or more. As we expected, a positive corre- lation (coefficient of .37 significant at the 0.01 level) occurred between stu- dents’ number of international Internet searches in the previous year and their extent of familiarity with conducting

research on foreign markets through the use of electronic information sources.

To determine possible effects of pre- vious experience, we partitioned stu- dents into two groups: those who per- formed no international Internet searches during the year before the assignment and those who had per- formed such searches. Through t tests of five relevant items, we compared the means of the two groups for significant differences for each item.

One interesting finding was that stu- dents with prior international Internet research assignments felt even greater increases of interest in international business compared with students with no such previous search experience. Also, students with and without previ- ous search experience felt approximate- ly equally satisfied with their gains and time invested in the assignment.

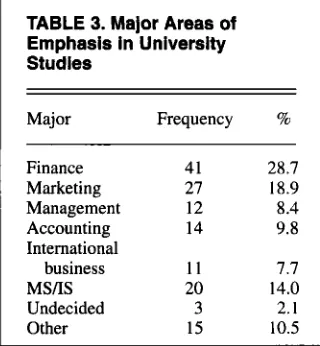

In Table 3, we display the student re- spondents’ major areas of emphasis in their university studies. The largest per- centage of students-one fourth- selected finance. Marketing was the dis- cipline with the second highest representation (18.9%), followed by management science and information systems (14.0%). Only 7.7% of the stu- dents selected international business.

Women made up 48.6% of our sam- ple, and men composed the remaining 51.4%. To explore possible gender dif- ferences, we performed t tests on each gender’s mean value for four key items. Gender manifested a significant effect (at the .05 level) only on number of hours spent completing the assignment. Women spent a mean of 7.28 hours, whereas men spent 6.39 hours. A fre-

TABLE 3. Major Areas of Emphasis in University Studies

Major Frequency %

~ ~~ Finance Marketing Management Accounting International

business

MSnS

Undecided Other

41 27 12 14

11 20 3 15

28.7 18.9 8.4 9.8

7.7 14.0 2.1 10.5

162 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for Business [image:6.612.404.564.567.740.2]quency distribution of years lived in the United States revealed that 74.5% of respondents had been residents for over

10 years.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Summary and Conclusions

Businesses delving into the global arena seek new hires with knowledge of international markets. Business schools, encouraged by the AACSB, have responded by internationalizing their curricula. Simultaneously, organizations hiring business school graduates and taxpayers supporting public universities expect accountability for what students learn. Our assessment of an internation- al Internet assignment distinguishes this pedagogical tool by accounting for skills learned and value-added to stu- dents who completed the assignment.

Results from the value-added portion of the assessment demonstrate distinct improvement in students’ familiarity with conducting research on foreign markets through electronic information sources. Ability to apply the concepts of segmentation and targeting to the inter- national marketplace and a rudimentary knowledge of how to conduct business in a foreign market improved dramati- cally, as reported by student respon- dents. The assignment also resulted in strong increases in students’ interest in further study of, or a possible career in, international business.

One important revelation from our study was that the vast majority of stu- dents used the Internet to conduct their research. Many student researchers went beyond simply consulting Inter- net sites; they reported investing an average of 7 hours on completion of

the assignment and over

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 hours onseeking relevant information on their targeted countries through the Internet alone. Despite those substantial time investments, over 80% of the students felt at least somewhat satisfied and almost 45% were very satisfied with their return on effort.

The assessment took place among a cross-section of mostly business under-

graduate students at a large, state-fund- ed university. One interesting finding was that, after completing the assign- ment, students with previous interna- tional Internet search experience report- ed a greater increase in interest in further study of, or a career in, interna- tional business compared with their inexperienced counterparts.

Although some of these measures may be suspect because they are self- assessments, they strongly corroborate instructors’ learning quality assess- ments based on tests and overall project evaluations. This assessment offers valuable insight into specific skills, knowledge and awareness learned, pro- ject sophistication, and extent of student effort and satisfaction with the assign- ment, as well as student characteristics that affect individual performance. As a result, faculty members may feel more confident that student skills, knowledge, and interest in international business will improve significantly with the use of this type of assignment in a compre- hensive business principles class.

REFERENCES

Abboushi,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

S., Lackman, C.,zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Peace, G. (1999).An international marketing curriculum

development & analysis. Journal of Teaching in

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

lnternational Business, 11, 1-19.

Adrian, M., & Palmer, D. (1999). Toward a model

for understanding and improving educational quality in the principles of marketing course.

Journal of Marketing Education, 21,25-33. American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of

Business (AACSB). (2000, May 9). Achieving

quality and continuous impmvement through selfevaluation andpeer review. St. Louis, MO: Author.

Arpan, J. S., Folks, W. R. & Kwok, C. C.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Y.(1993). International business education in the

1990’s: A global survey. St. Louis, MO:

AACSB Press.

Atwong, C., & Hugstad, P. (1997). Internet tech-

nology and the future of marketing education.

Journal of Marketing Education, 1 9 , 6 5 5 .

Atwong, C., Lange, I., Doak, L., & Aijo, T. (1996,

August 12). How collaborative learning spans the globe. Marketing News, 30, 16-19. Churchill, G.A., (1999). Marketing research:

Methodological foundations. Fort Worth, T X :

Harcourt Brace.

Fleming, M. J., Shooshtari, N. H., & Wallwork, S.

S. (1993). Internationalizing the business cur-

riculum: A survey of collegiate business schools. Journal of Teaching in International

Business, 5, 77-99.

Fugate, D., & Jefferson, R. (2001). Preparing for

globalization-Do we need structural change

for our academic programs? Journal of Educa- tion for Business, 76, 160-166.

Holmes, J., & Clizbe, E. (1997). Facing the 21st

century. Business Education Forum, 14,33-35.

Jarboe, G. R., McDaniel, C. D., & Lamb, C. W.

(1989). An investigation of marketing educa- tors’ time allocations to course content and teaching techniques for a one-term versus a

two-tern introductory marketing course. Pro-

ceedings of the AMA Summer Educators’ Con- ference, 47-52.

Johnson, D. M., & Mader, D. D. (1992). Interna-

tionalizing your marketing course: The foreign study tour alternative. Journal of Marketing

Education, 14, 26-33.

Kedia, B. L., & Cornwell, T.,B. (1994). Mission-

based strategies for internationalizing U S . business schools. Journal of Teaching in lnter-

national Business, 5, 11-29.

Lamb, C., Shipp, S., & Moncrief, W. (1995). Inte-

grating skills and content knowledge in the

marketing curriculum. Journal of Marketing

Education, 17, 1CL19.

Lamont, L., & Friedman, K. (1997). Meeting the

challenge to undergraduate marketing educa- tion. Journal of Marketing Education, 19,

Lawson, D., White, S., & Dimitriadis, S. (1998).

International business education and technolo- gy-based active learning: Student-reported ben- efit evaluations. Journal of Marketing Educa-

tion, 20, 141-148.

Manuel, T., Shooshtari, N., Fleming, M., & Wall-

work, S. (2001). Internationalization of the business curriculum at U.S. colleges and uni- versities. Journal of Teaching International

Business, 1 3 , 4 3 4 5 .

Miller, F., & Mangold, G. (1996). Developing

information technology skills in the marketing curriculum. Marketing Education Review, Spring, 29-39.

Natesan, C., & Smith, K. (1998). The Internet

educational tool in the global marketing class-

room. Journal of Marketing Education, 20, 149-160.

Siege], C. F. (1996). Using computer network (intranet and Internet) to enhance your stu- dents’ marketing skills. Journal of Marketing

Education, 18, 14-24.

Smart, D., Kelley, C., & Conant, J. (1999). Mar-

keting education in the year 2000: Changes observed and challenges anticipated. Journal of

Marketing Education, 21, 206-216.

Sterngold, A., & Hulbert, J. (1998). Information

literacy and the marketing curriculum: A multi- dimensional definition and practical applica- tion. Journal of Marketing Education, 20, 244-249.

Wright, L., Bitner, M J., & Zeithaml, V. (1994).

Paradigm shifts in business education: Using active learning to deliver services marketing content. Journal of Marketing Education, 16,

Zimrner, R. J., Bruce, G., & Lange, I. (1996). An

investigation of marketing educators’ approach to teaching international marketing in the intro- ductory marketing course. Journal of Teaching

in International Business, 8, 1-24.

17-30.

5-18.