Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:14

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Personal Values and Mission Statement: A

Reflective Activity to Aid Moral Development

Tyler Laird-Magee, Barbra Mae Gayle & Raymond Preiss

To cite this article: Tyler Laird-Magee, Barbra Mae Gayle & Raymond Preiss (2015) Personal Values and Mission Statement: A Reflective Activity to Aid Moral Development, Journal of Education for Business, 90:3, 156-163, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1007907

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1007907

Published online: 23 Feb 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 334

View related articles

Personal Values and Mission Statement: A

Reflective Activity to Aid Moral Development

Tyler Laird-Magee

Linfield College, McMinnville, Oregon, USA

Barbra Mae Gayle

University of Maryland University College-Europe, Adelphi, Maryland, USA

Raymond Preiss

Viterbo University, La Crosse, Wisconsin, USA

Personal values guide ethical decision-making behaviors. Business professors have traditionally addressed undergraduate ethics-based learning through a learn ethics approach using case studies, simulations, presentations, and other activities. Few offer a live ethics orientation requiring completion of a personal values self-assessment and creation of a personal values and mission statement through a reflective paper. Utilizing content analysis, the authors’ findings suggest that undergraduates’ narratives can serve as a cognitive developmental tool to actively engage ethical reasoning awareness and encourage moral formation and development within the learning environment.

Keywords: business ethics, ethics framework, marketing ethics, personal mission statement, personal values

To produce future business leaders with both personal and professional decision-making integrity, higher education must provide undergraduates with an opportunity to live ethics not just learn ethics (Solberg, Strong, & McGuire, 1995). Ethical reasoning—identifying right and wrong in personal and business contexts—requires understanding one’s personal values, ethical roles, and how to utilize this knowledge when facing workplace ethical dilemmas (Baker, Ya Ni, & VanWart, 2012). Knowing an individual’s personal values is fundamental as they guide moral judg-ments (Posner, Kouzes, & Schmidt, 1985). Students do not arrive at college without personal values, having been shaped by familial, cultural, and societal norms (Wadell & Davis, 2007). However, most students are not cognizant of their personal values, not having been forced to consider, reflect, and purposefully articulate them (Searight & Sea-right, 2011).

This study’s focus was to determine whether a specifi-cally designed assignment can enhance an undergraduate’s self-awareness of his or her personal values and sense of per-sonal mission. To provide a platform for this study, the fol-lowing literature review identifies pedagogical approaches to teaching ethics in business, specifically marketing.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Marketing professors have approached teaching ethics simi-larly as those in other business disciplines (Loe & Ferrell, 2001). Reviewing 500C ethics-related marketing articles appearing over 50 years in 58 journals, Schlegelmilch and Oberseder (2010) observed researchers focused on the “description of managerial actions when facing ethical situa-tions, but do not clarify how moral standards should be” (p. 14). Ferrell and Keig (2013) conducted an exploratory case study of business schools requiring a stand-alone marketing ethics course (n D 28) and found five conceptual

approaches: managerial, philosophical, cross-cultural, stakeholder focused, and society–social issues. Regardless

Correspondence should be addressed to Tyler Laird-Magee, Linfield College, Department of Business, 900 SE Baker Street, McMinnville, OR 97138, USA. E-mail: tlairdm@linfield.edu

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1007907

of approach, the researchers noted that most courses used significant classroom discussion, some type of individual paper, a group paper or presentation, and one or more case analysis assignments to learn ethics.

Moving beyond what might be called a learn ethics ped-agogy through the case study analysis approach, Solberg et al. (1995) proposed six recommendations for a live ethics pedagogy including: a student created class code of ethics and engaging in community service. Marketing professors who have personalized an ethical framework suggested by Solberg et al. (1995) for students by developing ethical codes of conduct have taken two paths. Either they have required students to create a code of conduct for an entire class to abide by (Buff & Yonkers, 2005; Kidwell, 2001) or they have required student groups in the forming stage to create a code of conduct to ensure work is done within agreed on standards (Buff & Yonkers, 2005; Solberg et al. 1995). Both approaches have proven effective student learning ethics models (Buff & Yonkers, 2005; Kidwell 2001) and have illustrated a viable alternative to the case study approach.

Other researchers have addressed the live ethics peda-gogy through community service engagement (Solberg et al., 1995). Sleeper, Schneider, Weber, and Weber (2006) explored if engaging in community service activities increase students’ ethical awareness by constructing the Business Education’s Role in Addressing Social Issues (BERSI) Likert-type scale. They determined of the under-graduate business students studied (n D 851) female students’ social issue attitudes were positively correlated with students’ past activities via donation, volunteerism, and non-profit organization work. Brown-Liburd and Porco (2011) studied undergraduate accounting students and showed three extra-curricular activities—internships, vol-unteer activities, and membership in Beta Alpha Psi— enhanced students’ levels of cognitive moral development.

Unless marketing students consider personal ethical sit-uations and ascribe meaning to their careers they are prone to intellectualize ethics instruction rather than apply ethics to a specific situation (Smith & VanDoren, 1989). This personalization process, Searight and Searight (2011) argued, should begin with students identifying their per-sonal values, rather than “uncritically taking on values and aspirations of others—typically an individual’s parents— and automatically using these as a personal guide for career and relationship issues” (p. 313).

Personal values are desires, beliefs, and choices (Argan-dona, 2003) are core to who an individual is (Posner, 2010), as they serve as a compass (Johnson, 2009) and shape individual behaviors (Rokeach, 1979) and character (Argandona, 2003). Personal values are related to moral reasoning (Lan, Gowing, McMahon, Rieger, & King, 2008), and are fundamental in facing ethical dilemmas, as they are used to assess and make ethical decisions (Gao & Bradley, 2007; Nonis & Swift, 2001). Thus, as Schein

(1978, 1987, 1992) argued each individual has a set of core values that have shaped his or her internal self-concept. These deeper values are taken for granted and result in behaviors that reflect the lived reality of those underlying values. If an individual can express her or his values those values can be inspected and debated, but most often these values are so deeply embedded that they remain non-negotiable and unrecognized even though they guide an individual’s actions.

Challenging students to understand their personal values is a fundamental step that aids in the development of an individual’s professional ethics. Kramer (1988) proposed a six-step experiential learning approach to address this issue. The second step, identifying and understanding an individu-al’s personal values, students are asked to pick five of Rokeach’s (1969) 18 instrumental values, those that give meaning to an individual’s life, and five of 18 terminal val-ues, a preferred state of existence or meaning (Rokeach, 1969). The five values students select from in each category are generally their greatest strengths (Kramer, 1988).

Hunt and Vitell (1986) explored the link between per-sonal ethics and developing professional ethics by propos-ing an early ethics decision-makpropos-ing model, the H-V theory of ethics. In subsequent research they validated five major gap categories between marketers and society: cultural environment, professional environment, industrial environ-ment, organizational environenviron-ment, and personal character-istics (Hunt & Vitell, 2006). Focusing on the personal characteristics component they included six interactive var-iables: religion, value system, belief system, strength of moral character, cognitive moral development, and ethical sensitivity (Hunt & Vitell, 2006). Each of these personal characteristic components offer complex dimensions for consideration as students walk through various steps to address an ethical dilemma until they arrive at a stage where they are “required to make choices and [are] encour-aged to examine their own personal moral codes, including their values systems” (Hunt & Vitell, 2006, p. 146). Schein (2001) suggested that organizations have established their cultural norms based on assumptions that are derived from individual values but those underlying values are rarely inspected or questioned until encountered in a variety of experiences in a new culture such as an organization.

Having examined or reflected on personal values through journaling gave business students a chance to set their ethical compass Gill (2012) argued. Integrating a reflective journal activity into an organizational psychology course, Searight and Searight (2011) challenged undergrad-uates to create a personal mission statement based on their identified values. Students reported this activity helpful, aiding them to clarify their personal values and time usage. The journaling approach supports the Deliberate Psycho-logical Education (DPE) model, a cognitive developmental theory which aids individuals in creating and interpreting meaning based on a purposeful and deliberate cognitive

PERSONAL VALUES AND MISSION STATEMENT: REFLECTIVE ACTIVITY 157

process (Schmidt, Davidson, & Adkins, 2013). DPE and application of its five core conditions that must be met within a learning environment—role-taking experience, support and challenge, reflection, balance of reflection and role-taking, and continuity—have been successfully applied to assess moral reasoning development in a variety of con-texts and student groups (Mosher & Sprinthall, 1971). The first undergraduate business student study to apply DPE to promote moral reasoning showed significant, positive results in a one-unit business ethics course (Schmidt, McA-dams, & Foster, 2009), providing a platform and recom-mended methodology to integrate this model into business curricula (Schmidt et al., 2013).

In summary, prior researchers have established opportu-nities for undergraduates to analyze ethical dilemmas with a learn ethics approach. A few studies exist with a live ethics orientation or are anchored in observed reality as Schein (1987) argued. Because research shows personal values are vital as they serve as a compass (Johnson, 2009) to effectively engage in ethical decision making, this pilot study examines if students early in their business pro-gram—an intro to marketing course—are cognizant and can explicitly identify their values and sense of personal mission, thereby equipping them with a personal foundation to more effectively engage in learn ethics activities embed-ded within a business curriculum.

METHODOLOGY

This pilot study linked the core business concept of a mis-sion statement by challenging students to create their own personal mission statement based on a clear articulation of their personal values. The two-part assignment: (a) the completion of an online values/strengths exercise which facilitated identifying personal values and a personal mis-sion statement and (b) a 1,500-word reflection paper that expanded on the first assignment as undergraduates dis-cussed their personal values and initial personal mission statement and how both form the platform to operationalize their personal ethics served as the data set.

The study was conducted at a Catholic university (Asso-ciation to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business accred-ited) and reflection papers from two sections of an intro to marketing course (n D50) were analyzed. To address this study’s goal of determining if a specifically designed assignment could enhance an undergraduate’s self-aware-ness of his or her personal values and sense of personal mis-sion, a content analysis was conducted using cognitive complexity as the theoretical lens.

Content analysis is used to systematically and objec-tively measure and analyze large amounts of written and oral communication (Berelson, 1952). The method relies on and incorporates: (a) objectivity–intersubjectivity, describe findings without bias; (b) an a priori design,

researchers must agree on units measured and coding pro-cedures before coding; (c) reliability,consistent results on repeated trials with two or more coders; (d) validity, mea-suring against well-defined parameters; (e) generalizability, application to other defined populations; (f) replicability, repeating study with similar outcomes (Neuendorf, 2002).

Cognitive complexity is a psychological construct, often integrated within the DPE model to assess cognitive and moral development (Brendel, Kolbert, & Foster, 2002). Assessed by the number of “perceptual constructs” used that are both “abstract” and “interconnected” (Infante, Rancer, & Womack, 1993, p. 149), cognitive complexity measures two dimensions: (a) differentiation, the number of interpersonal constructs a person uses; and (b) hierarchic integration, which determines the relationships between these constructs within a person’s cognitive system (Crockett, 1965).

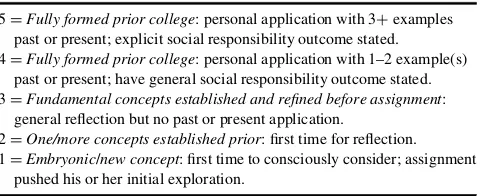

To begin analysis, one author (T. L-M.) conducted a sampling of every fifth paper using a coding schema that analyzed the units (message component), as Neuendorf (2002) recommended. Through the process of isolating the-matic units of measurement content categories evolved. Based on initial content analysis, a two-step research meth-odology emerged. For Step 1 all papers were coded based on a 5-point Likert-type scale using a cognitive complex-ity-based interpretation of each paper overall (Table 1).

After agreement of the units measured and method, two coders, one author and another colleague, read the 50, 3–5-page reflection papers and determined in which of the five cognitive-complexity based categories each paper belonged. Both coders compared their coding assessments, producing 90% agreement. For the 10% where there was no agreement, a dialogue followed until both coders agreed on the appro-priate ranking for each paper in question, which is in keeping with content analysis standards (Neuendorf, 2002).

RESULTS

All students (nD50) were 19–20 years old and were either

first semester sophomores or juniors. Fifty-four percent (n D27) were women and 80% (n D40) of the students were Caucasian. Nine were Asian or Pacific Islander; one was Hispanic.

TABLE 1

Cognitive Complexity: Likert-Type Scale Definitions

5DFully formed prior college: personal application with 3Cexamples past or present; explicit social responsibility outcome stated.

4DFully formed prior college: personal application with 1–2 example(s) past or present; have general social responsibility outcome stated. 3DFundamental concepts established and refined before assignment:

general reflection but no past or present application.

2DOne/more concepts established prior: first time for reflection. 1DEmbryonic/new concept: first time to consciously consider; assignment

pushed his or her initial exploration.

Step 1: Cognitive Complexity Assessment

A content analysis of 50 values–mission statement reflective papers revealed that 76% (n D 38) of the stu-dents (papers coded as having a general reflection but no past or present application or less awareness) were placed in the embryonic to fundamental stages of articu-lating their individual values. Two examples of the responses that illustrated that for some students (n D 6)

this was the first time to consciously consider their val-ues included: “There are many ways to be dishonest. Stealing is one way. Although I find myself doing so [stealing] every once in a while, I cannot stop myself.” A second student example: “My parents gave me an amazing look at who I am not striving to be.”

Thirty-eight percent of the students (nD19) used one or more values-based concepts, but appeared to be doing so for the first time. One student reported that: “I have two perspec-tives in my life: to be happy and be responsible. . .being

responsible makes me happy, so that’s basically why I do it.” A second student offered: “I do think it’s time to address these questions [values and beliefs] because ultimately they shape who you are and how you act as a person.”

Additionally, 26% (n D 13) of the students identified

values-based concepts that had been established and refined before the assignment but had no past/present application. One student said: “Learning to trust is something I have worked very hard on in the last year.. . .I can’t judge

every-one based on a few bad experiences with people who I thought were my friends.” A second offered: “I examined two organizations I have been involved in, Boy Scouts and Air Force ROTC, and one thing I was taught [through them] was in making the wrong decision now can better my making of the right one later.”

Two categories of papers identified students as having formed their personal values prior to entering the university and connected these values with either past or present deci-sions to explicitly engage in social responsibility behaviors. The sole difference between the two categories was the number of examples students provided. Fifteen percent (n D8) of the students provided one or two examples of

past or personal application of values-based behaviors. One example was the following:

My parents have instilled their values in me. . .hard work,

determination, and perseverance; they have shown me that anything is possible. As immigrants to the U.S. at a young age, they had little money and barely spoke English. . .their

goal was to work hard to give my brothers and me every-thing they didn’t have. . .they have inspired me to use my

skills and resources to help others who are less fortunate.

Nearly 10% (n D 5) were fully formed and explicitly

connected this self-knowledge outcome with three or more specific, social responsibility behaviors tied to current or

future actions. One student’s response captured the essence of this category:

Above all else, an individual possesses his/her own values and beliefs. I feel that everyone governs their decisions through the implementation of these principles. Professing and identifying such mindsets reveal a great deal about a person’s personality. From an ethical perspective, I feel that my Catholic religion plays a very prevalent role in my daily life. However, the traits that I attempt to embody the most focus on three main elements: my family, hard work and a sense of gratefulness. These three qualities serve as pillars for how I live my life and approach each day.

Step 2: Values Influencers Precollege

A second level of content analysis followed to determine what specifically influenced the 25% of the students whose papers showed that they were fully aware of their personal values before entering college and had articulated a per-sonal decision to give back to others. In this new coding schema, sentences were the units measured and descriptive words or constructs (nD267) which related to each of the

identified recurring categories in 13 papers were recorded as either values influencers (what externally influenced stu-dent thinking) or social responsibility influencers (what was the result of the types of service-related activities; see Appendixes A and B).

The values influencer categories (n D 207; i.e., what externally influenced students) included: family, 27%, reli-gion 27%, physical challenge, 6%, ethnic culture, 6%, secu-lar reference, 7%, and school, 3%. The social responsibility categories (n D 60; i.e., specific identification of past or future behaviors) included: back, general, 6%; give-back, specific, 2%; and others orientation, 15%. It is inter-esting to note when comparing papers coded with three or more examples of past or personal application of values-based behaviors constructs with those coded with one or two examples of past or personal application of values-based behaviors revealed three differences.

Papers coded with three or more past or personal appli-cation of values-based behaviors were much higher in rec-ognizing the role that religion (n D 52) played in their

values formulation when compared with papers coded with one or two examples of past or personal application of val-ues-based behaviors (nD21). In contrast, papers coded one or two examples of past or personal application of values-based behaviors (nD8) identified the role of family (nD

44) as being much more influential than those coded with three or more examples of past or personal application of values-based behaviors (nD28). Additionally, those coded with one or two examples of past or personal application of values-based behaviors who identified that they would take action to give back showed more of a self-orientation (nD

11) while those coded with three or more examples of past

PERSONAL VALUES AND MISSION STATEMENT: REFLECTIVE ACTIVITY 159

or personal application of values-based behaviors identified an others orientation (nD24).

Examining the papers coded with three or more examples of past or personal application of values-based behaviors qualitatively, suggested that at the core there were personal or family related major events that crystallized all five students’ thinking. Their thinking reveals a framework where each student related additional constructs or life events from which they built their viewpoint. These life changing events included: being adopted, being the big sister to a retarded older brother, a church service trip to New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina, a grandfather’s unsuc-cessful two-year fight with cancer, and being dyslexic.

Additionally, demographics of the students whose papers were coded with three or more examples of past or personal application of values-based behaviors (n D 5) were mostly women (n D4) and Caucasian (n D4). Stu-dents whose papers were coded with one or two examples of past or personal application of values-based behaviors (n D 8) were men (n D 4), women (n D 4), and mostly Caucasian (nD7).

DISCUSSION

This pilot study illustrated a live ethics pedagogical approach through a reflective paper can offer a useful first step for undergraduates to explore their personal values sys-tem before embarking on a learn ethics approach. All stu-dents in this study identified this reflective paper as their first time to purposefully write their personal values on paper that is consistent with the business and ethics studies reviewed. As only 25% of this study’s business students could articulate a firm understanding of their own personal values, it would be a difficult to assume these students could engage in ethical decision-making activities or navigate case studies successfully, although researchers utilize this ethics instruction method (Agarwal & Malloy, 2002; Allan & Wood, 2009; Laditka & Houck, 2006; Warnell, 2010).

As Schmidt et al. (2013) suggested most of the students in this study were more aware of their values after pur-posely thinking about their personal characteristics in the assignment and what they actually valued. Their responses indicated that the majority of students when exploring those values focused on fundamentals such as their parents’ value system or the way their parents, the church, or some com-munity organization had instilled strength of moral charac-ter. Yet their descriptions did not yet illustrate a deep cognitive moral development or the ethical sensitivity that Hunt and Vitell (2006) suggested were necessary compo-nents for ethical decision making.

Several students reported that the assignment had chal-lenged them to clarify their personal values as Searight and Searight (2011) and Schmidt et al. (2013) argued was a first step in creating the sensibilities to engage in ethical

decision-making. However, these students had not yet for-mulated how their personal values would be related to the decisions they would be facing during their careers as Lan et al. (2008),Gao and Bradley (2007) and Nonis and Swift (2001) articulated was a necessary first step in ethical deci-sion making. The 5% of students whose response illustrated that their values were fully formed and clarified before coming to college discussed how their values were funda-mental to who they were as a person (Johnson, 2009; Pos-ner, 2010), how these values had influenced their behavior (Rokeach, 1979) and shaped their character (Argandona, 2003). These students suggested as Schein (1996) claimed that these core values shaped their behaviors so that they lived those values.

Another lived ethics experience surfaced from student responses as a formative, experiential learning experience for students who had fully formed values and could articu-late them. All five students in this category consciously linked their stated values as playing a crucial role in con-necting with personal accountability via community ser-vice—part of their personal mission—in past or future planned behaviors. Community service was seen as enhanc-ing undergraduates’ moral development and is supported by other research (Boss, 1994; Brown-Liburd & Porco, 2011). Sleeper et al. (2006) also found community service skewed more heavily toward women but only three of the eight women identified community service behaviors as a per-sonal value in this study.

Additionally all five students with fully formed values prior to college reported that their religious training played a tremendous role in their values formation. As Wilkes, Burnett, and Howell’s (1986) work illustrated the students’ personal religious values play a strong role in their values-based decisions in this study. Additionally, the students’ responses illustrate as Hunt and Vitell (2006) argued the degree of religion’s importance in an individual’s everyday life.

Clearly, this pilot study had a number of limitations: (a) the study was fielded at only one university, and as a Catho-lic university this could have skewed the number of stu-dents who may have more personal values awareness due to religion than others; (b) only traditionally aged under-graduate students were examined and while necessary to establish an individual’s values, this population is still in the formative stages of moral development; and (c) the size of the population pool was very small and did not provide statistical significance.

This study’s results suggest using personal values identi-fication and integration—regardless of business course taught—as a foundation to build from can enhance other ethics-based learning activities within a business curricu-lum. As such, this study supports and provides an additional moral growth activity, which can be embedded within the proposed DPE approach for business curriculum design (Schmidt et al., 2013). As we noted, to satisfy inclusion of

“purposeful reflective activities” (Schmidt et al., 2003, p. 132) this assignment can be added to the reflective jour-nals suggested throughout the semester and coupled with instructor-assisted guidance. Alternatively, this two-part reflective paper could serve as the first assignment within a student’s first DPE course and as a last assignment during the capstone course, thereby giving business students a chance to reflect on what or if any changes have occurred during college. Certainly assessment of these pre- and post-college experiences would provide additional insights into what external values influencers have purposefully or acci-dentally been integrated into students’ college experiences.

As a pilot study, the results from this initial research can be expanded to a larger, more statistically reliable and valid sample beyond the student population of one Catholic uni-versity to other private or public universities and compare and contrast student population findings. This would pro-vide a broader view into different student populations and what or if any differences exist in how students identify their personal values and what personal characteristics are more influential in how they articulate their personal mis-sion statements.

Integration of this assignment would also increase indi-vidual students’ opportunities to consider how their per-sonal characteristics—religion, value system, belief system, strength of moral character, cognitive moral devel-opment, and ethical sensitivity (Hunt & Vitell, 2006)—can be impacted, just as they could be in real marketing or busi-ness ethical dilemmas. Certainly one could test two groups: one with this integration and one without to determine to what degree students, through a reflective instrument, were better able or felt more qualified to make ethical-based decisions that were congruent with their personal values.

It can be concluded, based on candid and very personal papers written by these 50 undergraduate students, it is pos-sible for business professors—regardless of discipline—to provide the platform for individual values reflection by requiring the development of each student’s initial mission statement via a two-part homework assignment. Students saw this as an opportunity they would not have done with-out being required to do so for this marketing course. This approach aligns with Swanson and Fisher (2008) who admonished that the key to learning ethics is to discover ways for students to first reflect inwardly as it serves as a basis for understanding others.

REFERENCES

Agarwal, J., & Malloy, D. C. (2002). An integrated model of ethical deci-sion-making: A proposed pedagogical framework for a marketing ethics curriculum.Teaching Business Ethics,6, 245–268.

Allan, D., & Wood, N. T. (2009). Incorporating ethics into the marketing communications class: The case of old Joe and new Joe Camel. Market-ing Education Review,19, 63–71.

Argandona, A. (2003). Fostering values in organizations.Journal of Busi-ness Ethics,45, 15–28.

Baker, D. L., Ya Ni, A., & Van Wart, M. (2012). AACSB assurance of learning: Lessons learned in ethics module development.Business Edu-cation Innovation Journal,4, 19–27.

Berelson, B. (1952).Content analysis in communication research. Glen-coe, IL: Free Press.

Boss, J. A. (1994). The effect of community service work on the moral development of college ethics students.Journal of Moral Education,23, 183–194.

Brendel, J. M., Kolbert, J. B., & Foster, V. A. (2002). Promoting student cognitive development.Journal of Adult Development,9, 217–226. Brown-Liburd, H. L., & Porco, B. M. (2011). It’s what’s outside that

counts: Do extracurricular experiences affect the cognitive moral devel-opment of undergraduate accounting students? Issues in Accounting Education,26, 439–454.

Buff, C. L., & Yonkers, V. (2005). Using student generated codes of con-duct in the classroom to reinforce business ethics education.Journal of Business Ethics,61, 101–110.

Crockett, W. H. (1965). Cognitive complexity and impression formation. InProgress in experimental personality research(vol. 2). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Ferrell, O. C., & Keig, D. L. (2013). The marketing ethics course: Current state and future directions. Journal of Marketing Education, 35, 119–128.

Gao, Y., & Bradley, F. (2007). Engendering a market orientation: explor-ing the invisible role of leaders’ personal values.Journal of Strategic Marketing,15, 79–89.

Gill, L. (2012). Systemic action research for ethics students: Curbing unethical business behaviour by addressing core values in next genera-tion corporates.Systematic Practice & Action Research,25, 371–391. Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. J. (1986). A general theory of marketing ethics: A

partial test of the model.Journal of Macromarketing,6, 5–15.

Hunt, S. D., & Vitell, S. J. (2006). The general theory of marketing ethics: A revision and three questions. Journal of Macromarketing, 26, 143–153.

Infante, D. A., Rancer, A. S., & Womack, D. F. (1993).Building communi-cation theory(2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: Waveland Press, Inc.

Johnson, C. E. (2009).Meeting the ethical challenges of leadership: Cast-ing light or castCast-ing shadow. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kidwell, L. A. (2001). Student honor codes as a tool for teaching profes-sional ethics.Journal of Business Ethics,29, 45–49.

Kramer, H. E. (1988). Applying marketing strategy and personal value analysis to career planning: An experiential approach.Journal of Mar-keting Education,10, 69–73.

Laditka, S. B., & Houck, M. M. (2006). Student-developed case studies: An experiential approach for teaching ethics in management.Journal of Business Ethics,64, 157–167.

Lan, G., Gowing, M., McMahon, S., Rieger, F., & King, N. (2008). A study of the relationship between personal values and moral reasoning of undergraduate business students. Journal of Business Ethics, 78, 121–139.

Loe, T. W., & Ferrell, L. (2001). Teaching marketing in the 21st century.

Marketing Education Review,11(2), 1–16.

Mosher, R., & Sprinthall, N. A. (1971). Deliberate psychological educa-tion.Counseling Psychologists,2(4), 3–82.

Neuendorf, K. A. (2002).The content analysis guidebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Nonis, S., & Swift, C. O. (2001). Personal value profiles and ethical busi-ness decisions.Journal of Education for Business,76, 251–256. Posner, B. Z. (2010). Values and the American manager: A three-decade

perspective.Journal of Business Ethics,91, 457–465.

Posner, B. Z., Kouzes, J. M., & Schmidt, W. H. (1985). Shared values make a difference: An empirical test of corporate culture. Human Resource Management,24, 293–309.

PERSONAL VALUES AND MISSION STATEMENT: REFLECTIVE ACTIVITY 161

Rokeach, M. (1969).Beliefs, attitudes and values. San Francisco, CA: Jos-sey-Bass.

Rokeach, M. (1979).Understanding human values: Individual and socie-tal. New York, NY: Free Press.

Schein, E. H. (1978).Career dynamics: Matching individual and organiza-tional needs.Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Schein, E. H. (1987).The clinical perspective in fieldwork. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Schein, E. H. (1992).Organizational culture and leadership(2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schein, E. H. (1996). Career anchors revisited: Implications for career development in the 21st century.Academy of Management Executive,

10(4), 80–88.

Schlegelmilch, B. B., & Oberseder, M. (2010). Half a century of marketing ethics: Shifting perspectives and emerging trends.Journal of Business Ethics,93, 1–19.

Schmidt, C. D., Davidson, K. M., & Adkins, C. (2013). Applying what works: A case for deliberate psychological education in undergraduate business ethics.Journal of Education for Business,88, 127–135. Schmidt, C. D., McAdams, C. R., & Foster, V. (2009). Promoting the

moral reasoning of undergraduate business students through a deliberate psychological education-based classroom intervention.Journal of Moral Education,38, 315–334.

Searight, B. K., & Searight, H. R. (2011). The value of personal mis-sion statements for university graduates. Creative Education, 2, 313–315.

Sleeper, B. J., Schneider, K. C., Weber, P. S., & Weber, J. E. (2006). Scale and study of student attitudes toward business education’s role in addressing social issues. Journal of Business Ethics, 68, 381–391.

Smith, L. W., & VanDoren, D. C. (1989). Teaching marketing ethics: A personal approach.Journal of Marketing Education,11(2), 3–9. Solberg, J., Strong, K. C., & McGuire, C. Jr. (1995). Living (not learning)

ethics.Journal of Business Ethics,14, 71–81.

Swanson, D. L., & Fisher, D. G. (2008).Advancing business ethics educa-tion. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Wadell, P. J., & Davis, D. H. (2007). Tracking the toxins of Acedia: Re-envisioning moral education. In D. V. Henry & M. D. Beatty (Eds.),The schooled heart: Moral formation in American higher education

(pp. 133–153). Waco, TX: Baylor University Press.

Warnell, J. M. (2010). An undergraduate business ethics curriculum: Learning and moral development outcomes.Journal of Business Ethics Education,7, 63–84.

Wilkes, R. E., Burnett, J. J., & Howell, R. D. (1986). On the meaning and measurement of religiosity in consumer research.Academy of Marketing Science,14, 47–56.

APPENDIX A: SECOND RUBRIC—SCORING “5” CODED PAPERS (nD5)

Values influencers Inputs Total

Family Mom/dad Grandparents Sibling Other family Other

16 5 7 28

Spirituality/religion Jesus/God Scripture verse Catholic Non-Catholic “My faith” Other

12 18 6 4 2 10 52

Physical challenge Self Mom/dad/sibling Grandparents Other family Other

3 1 4

Ethnic culture Self ethnicity Parents’ ethnicity Other family Ancestors Other

3 1 4

Secular reference Quote Book Event Sports Other

9 4 13

School Teacher: Any Current university Marketing class Group project Other

3 2 2 7

Social responsibility Outputs

Give back: General Own culture Any culture Other

7 7

Give back: Specific Environment Poor World: General Religious Other

4 4

Others orientation Self-oriented Family oriented Others oriented Friends Other

10 10 4 24

APPENDIX B: SECOND RUBRIC—SCORING “4” CODED PAPERS (nD8)

Values influencers Inputs Total

Family Mom/dad Grandparents Sibling Other family Other

39 3 1 1 44

Spirituality/religion Jesus/God Scripture verse Catholic Non-Catholic “My faith” Other

13 2 3 3 21

Physical challenge Self Mom/dad/sibling Grandparents Other family Other

12 12

Ethnic culture Self ethnicity Parents’ ethnicity Other family Ancestors Other

2 3 1 6

Secular reference Quote Book Event Sports Other

10 3 1 14

School Teacher: Any Current university Marketing class Group project Other

2 2

Social responsibility Outputs

Give back: General Own culture Any culture Other

9 9

Give back: Specific Environment Poor World: General Religious Other

0 Others orientation Self-oriented Family oriented Others oriented Friends Other

11 5 16

PERSONAL VALUES AND MISSION STATEMENT: REFLECTIVE ACTIVITY 163