www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Behaviour of 3-week weaned pigs in Straw-Flow

w,

deep straw and flatdeck housing systems

H.R.C. Kelly

a,), J.M. Bruce

a, P.R. English

b, V.R. Fowler

b,

S.A. Edwards

a,1 aSAC, Ferguson Building, Craibstone Estate, Bucksburn, Aberdeen AB21 9YA, UK

b

Department of Agriculture, UniÕersity of Aberdeen, MacRobert Building, 581 King Street,

Aberdeen AB24 5UA UK

Accepted 31 January 2000

Abstract

The behaviour of 3-week weaned pigs in different housing systems was examined as part of an assessment of the suitability of the Straw-Floww

system for pigs of this age. Three replicate pens

Ž . Ž . w

Ž . of 20 pigs were weaned at 6.4 kg liveweight into each of: a deep-straw; b Straw-Flow ; c

Ž . Ž . Ž .

large flatdeck; d small flatdeck. A kenneled lying area was provided in a and b . The floor in Ž .c and d was expanded metal. Stocking densities were 0.23 mŽ . 2rpig in a , b and c , and 0.17Ž . Ž . Ž .

2 Ž . Ž .

mrpig in d . After 4–5 weeks at 19.6 kg liveweight , 16 pigs from each pen were moved into w

Ž 2 .

Straw-Flow grower pens 0.68 mrpig and observed until slaughter at 90.6 kg. Pigs in systems Ž

incorporating straw showed behaviour patterns associated with increased welfare greater straw-di-.

rected behaviour and less pig-directed and pen-directed behaviour relative to those in barren pens. Ž . Ž .

Behavioural differences between a and b related to differences in available straw; there were

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

few differences between c and d . Pigs from c and d showed increased rooting relative to Ž .

those from a after transfer to the grower pens, but other behavioural differences between weaner treatments did not persist. It is concluded that the Straw-Floww

system can provide suitable accommodation for weaned pigs.q2000 Published by Elsevier Science B.V. Allrights reserved.

Keywords: Pig-housing; Straw; Welfare; Behaviour

)Corresponding author. Present address: Department of Agriculture, University of Aberdeen, MacRobert

Building, 581 King Street, Aberdeen AB24 5UA, UK. Tel.:q44-1224-274122; fax:q44-1224-273731.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] H.R.C. Kelly .

1

Present address: Department of Agriculture, University of Aberdeen, MacRobert Building, 581 King Street, Aberdeen AB24 5UA, UK.

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Published by Elsevier Science B.V. Allrights reserved.

Ž .

1. Introduction

Housing with fully perforated floors is commonly used for early-weaned pigs, since this encourages the physical separation of the pig and its dung, and allows increased stocking density. However, the behavioural and other disadvantages of this type of

Ž .

housing are well documented for example, van Putten and Dammers, 1976 . Bedded housing systems may redress the behavioural problems but can encourage enteric

Ž .

problems for example, Silver, 1989 , and have other practical management disadvan-tages such as increased labour requirement. The Straw-Floww

housing system was developed to provide the welfare advantages of straw without the associated

manage-Ž .

ment disadvantages Bruce, 1990 , and was shown to be successful in this for

Ž .

growingrfinishing pigs by Lyons et al. 1995 .

In evaluating a new housing system for its effects on animal welfare, many factors

Ž .

must be taken into consideration. Broom 1989 stated that ‘‘The welfare of an individual is its state as regards its attempts to cope with its environment’’. Welfare can therefore be assessed by measuring the extent of coping strategies, one form of which involve behavioural modification. Abnormal behaviour is not necessarily a sign of

Ž .

suffering Dawkins, 1980 , and should be interpreted with caution. However, a compari-son of behaviour in different environments can provide indications of modified patterns, and identify whether one system leads to the performance of more potentially harmful behaviours than another. The built environment may lead directly to abnormal be-haviours, for example by restricting movement, or providing slippery floors which may

Ž

lead to abnormal methods of lying and rising, and a reluctance to change posture Fraser

.

and Broom, 1990 . It may also give rise indirectly to abnormal behaviour by failing to provide adequate circumstances for appropriate expression of highly motivated be-haviours. Thus, changes in activity patterns, pen-directed behaviours and pig-directed behaviours may be indicative of housing inadequacy. Such behavioural assessment should then be combined with assessment of other welfare parameters to arrive at an overall conclusion. This paper describes a behavioural investigation into the suitability of Straw-Flow for early-weaned pigs, when compared with systems chosen to reflect the range of other housing in curent commercial use. The long-term effects of weaner housing are also considered, since residual influences of the early housing environment

Ž .

have previously been reported in pigs for example, Boe, 1993 . Other, nonbehavioural

Ž . Ž .

aspects of the investigation are described by Kelly et al. 1998 , and Kelly et al. 2000 .

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Pen design

Ža and b were built within the same room. Both initially had a kennel covering the lying.

area. This was constructed of two overlapping sheets of 10-mm plywood, with 125-mm-wide plastic-strip curtain across the front to allow easy access for pigs while conserving heat. The roof sheets moved independently, so that the kenneled area could

Ž .

be expanded as the pigs grew. Two flatdecks c and d were built within a second room, both with fully perforated floors. There are many types of flooring available; however 2073F galvanised expanded metal was considered to be the most commonly used type on farms. The pen floor was 790 mm above the ground, providing under-floor slurry storage. Waste was disposed of after each group of pigs had been removed. No bedding was provided. Pens in all systems were thoroughly cleaned between replicates.

Ž .a Deep-straw. The pen measured 2.75 2 2 Ž

=1.76 m providing 0.23 m rpig excluding

.

feeder area . Bedding was allowed to build up, straw being supplied as necessary to maintain a clean, dry lying area. Manure was removed about three times per replicate, as necessary to maintain a clean, dry lying area. Straw was supplied, 141.6 kg in total

Žmean of three replicates , 4.4 times the amount provided to the Straw-Flow pen. There.

was a double-glazed window in the pen wall to allow observation of behaviour within the kennelled area.

Ž .b Straw-Flow see Fig. 1 . This pen had the same dimensions as a. The concreteŽ .

Ž .

floor sloped at 1:16, with a 100 mm step down into the dunging area 600 mm wide . There was a gate at the front of the pen with a 75 mm gap beneath it to allow dung to pass out of the pen There was a double-glazed window in the pen wall to allow observation of behaviour within the kennelled area. One kilogram straw was placed in

Ž

the pen before the pigs arrived. A further 1 kg was supplied each day 0.5 kg at 0900 h,

.

and 0.5 kg at 1700 h, after the day’s observations were complete . The straw was shaken apart inside the kennel. Waste straw and manure accumulated outside the pen and were removed daily. The straw provided was not sufficient to allow a bedded layer to accumulate, but a ‘‘crust’’ formed over the surface of the lying area, comprising straw, feed, skin, dung etc.

Fig. 1. Elevation of the Straw-Floww

Ž .c ‘‘Large’’ flatdeck. This pen had the same dimensions as a and b , providingŽ . Ž .

0.23 m2rpig.

Ž .d ‘‘Small’’ flatdeck. This pen was constructed to represent commercial practice,

measuring 3.05=1.22 m2 and providing 0.17 m2rpig.

Ž .e Grower pens. The grower pens, which were together within the same room, were all of Straw-Flow design, measuring 2.7=4.0 m2 providing 0.68 m2

rpig for 16 pigs. The step down into the dunging area was 100 mm, with a 100-mm gap under the gate. Each pen was provided with one double-space feeder with shoulder guards, and two bite drinkers which had guards and a stepping block to enable smaller pigs to reach the

Ž .

drinkers easily. Straw 1.9 kg per pen per day was provided via a self-help dispenser, giving the same amount of straw per floor area as the weaner pen.

2.2. Animals

In each replicate, 20 three- to four-week-old entire male pigs from the same farm were weaned into one pen of each system on the same day, with initial weight balanced across the treatments. All of the pigs received from the breeding farms had been tail

Ž .

docked shortly after birth. Replicate one Landrace=Large White came from one farm,

Ž .

replicates two and three Landrace=Duroc=Large White from another. The grower pens could accommodate only 16 pigs at 90 kg liveweight. In the first replicate, the four ‘‘extra’’ pigs were removed from each pen at 40 kg liveweight. In the second and third replicates, the four ‘‘extra’’ pigs were removed at the time of transfer to the grower pens.

2.3. Management

Ž .

During the post-weaning period, pigs were inspected twice daily 0900 and 1700 h . Low-level lighting was used continuously to permit video recording of pig behaviour, although no video data are presented in this paper. Fluorescent lighting was available to permit inspection and observations. Both rooms were maintained under the same lighting regime, with fluorescent lighting switched on between the morning and evening inspections. The set temperature within each room was adjusted according to the pigs’

Ž

changing requirements, as determined by the computer model ‘‘PigCrit’’ Bruce and

.

Clark, 1979 , which calculates upper and lower critical temperatures for young pigs. Straw bedding reduces the lower critical temperature of a group of pigs relative to lying on bare concrete, and a kennel over the lying area retains heat produced by the pigs. This made it appropriate to operate the straw room at a lower temperature than the flatdeck room, with the pigs remaining within their thermoneutral zones. The recorded mean temperature over the three replicates in the straw room was initially 238C, decreasing to 168C by the end of the weaner period, and in the flatdeck room 278C, decreasing to 188C. The pigs were transferred to the grower pens after 4 weeks

Žreplicates 1 and 2 or 5 weeks replicate 3 in the weaner pens at a liveweight of 19.6. Ž . Ž .

2.4. Daytime behaÕiour recording

In this study, scan sampling was the method of choice for behaviour recording because it provides ‘‘a reasonably accurate estimate of the amounts or percentages of

Ž .

time individuals or group members spend in particular activities’’ Banks, 1982 . It also allowed all four treatment groups to be observed contemporarily by the same observer.

Ž .

In replicate one, 12 animals per pen were selected for observation ‘‘focal animals’’ to provide a spread of weights at weaning. In replicates two and three, 14 focal animals were selected. The same animals were observed throughout the study, regardless of subsequent performance. Some focal animals were removed when the groups were split; however, 10 focal animals remained in each group during the grower stage.

Ž

At each timepoint, each focal animal’s activity was recorded in terms of posture 1 of

. Ž . Ž .

5 possible , behaviour 1 of 18 and substrate 1 of 17 . Some activities were observed to occur only rarely, and so were subsequently combined for statistical analysis where appropriate. A detailed description of the categories analysed is provided in Table 1. Of

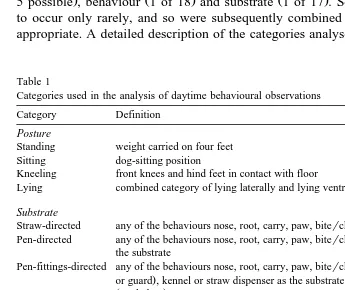

Table 1

Categories used in the analysis of daytime behavioural observations

Category Definition

Posture

Standing weight carried on four feet Sitting dog-sitting position

Kneeling front knees and hind feet in contact with floor Lying combined category of lying laterally and lying ventrally

Substrate

Straw-directed any of the behaviours nose, root, carry, paw, biterchew with straw as the substrate Pen-directed any of the behaviours nose, root, carry, paw, biterchew with floor, walls or fence as

the substrate

Ž

Pen-fittings-directed any of the behaviours nose, root, carry, paw, biterchew with feeder, drinker or block

.

or guard , kennel or straw dispenser as the substrate, except maintenance behaviours

Žsee below.

Ž . Ž .

Pig-directed nose ‘‘social behaviour’’ , root, paw, biterchew ‘‘nonsocial behaviour’’ any part of

Ž .

another pig tail, ear and abdomen recorded separately ; shoverpush pig, avoid, fleer

Ž .

squeal aggression or playfighting recorded separately ; mount pig

BehaÕiour

a

Maintenance feed at feeder , drink at drinker, await feeder or drinker, eliminate urine or dung, rub, stretch, yawn, cough, vomit

Motion walking around pen; no obvious other behaviour

Ž .

Inactive activity and substrate both recorded as ‘‘none’’ any posture Total play runningrscampering, playfighting

Vacuum chewing chewing with no visible substrate

Total nosing nasal disc applied to any substrate without pressure

Total rooting nasal disc applied to any substrate with pressure and forward movement Total chewing any substrate taken into mouth and jaw movements made

a

these, behaviours directed at the pen and pen fittings were considered to be detrimental as there was the possibility of injury to the pig as well as the development of stereotypies. Nonsocial pig-directed behaviour was also considered to be undesirable because of the risk of injury to the recipient. Some other behaviours, although not necesssarily overtly harmful, were also considered to be detrimental as indicative of coping difficulty if performed over long periods of time, for example inactivity and vacuum chewing. Behaviours which were considered to be ‘‘beneficial’’ included play

ŽDybkjaer, 1992 , and straw-directed behaviour, as straw offers the opportunity for a.

variety of different manipulations and provides a substrate for the strong foragingr ex-ploratory motivation of young pigs. Similar distinctions have been made by other

Ž .

authors, for example Boe 1993 .

The pigs were allowed to settle for 30–60 min after the daily feeding routine was completed. This period was considered necessary, as the stock people had to enter the pens to clean and refill the hoppers, check drinkers and deliver straw, and thus influenced the pigs’ behaviour. Behaviour was recorded at 30-min intervals between 1030 and 1700 h. Where it proved impossible to complete the observation cycle during the 30 min, the recording interval was extended. This was particularly necessary during the weaner period, when additional time was required to move quietly in and out of the separate weaner rooms.

The observer was always positioned outside the pens to gain a clear view of the pigs’ activity but making no attempt to hide from them. After entering the room, the observer allowed 2–3 min to elapse before starting to record behaviour, to allow any interest caused by her entry to subside. Generally the pigs ignored the observer, who was familiar to them. All observations were recorded by the same person throughout the study. The pigs within each pen were always observed in the same order. The weaner pens were always observed in the order: small flatdeck, large flatdeck, Straw-Flow, deep straw. The grower pens were also always observed in the same order but, as the groups of pigs were transferred from the weaner pens in a randomised manner, the grower pen order did not necessarily reflect the weaner pen order.

Behaviour was recorded on 3 days in each week. Since the behaviour of pigs in the same pen was not independent, all the observations collected in each pen over the 3-day period were summed, to produce a frequency of occurrence of each behaviour in each pen for that ‘‘week’’. These are expressed in the results as a percentage of the total number of recorded observations. Behaviour was recorded and analysed each week in the weaner pens, and for the first, second, fifth and eighth week in the grower pens. In addition, these results were summed to produce a total for the weaner and grower periods.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Data, as defined above, were analysed as pen means by two-way analysis of variance.

Ž . Ž .

Treatment 3 df and replicate 2 df were used as factors in the analysis, leaving 6 df for the error term. Where the data were found to be not normally distributed, they were

Ž .

normalised using a square root transformation. A GLM procedure Minitab 9.2 , which

Ž .

GLM analysis indicated significance, pairwise comparison of the treatment means was made using the method of least significant difference.

3. Results

3.1. Weaner period

There were no significant differences between treatments in the percentage of observations spent standing, kneeling, lying or in pen-fittings-directed or maintenance behaviours. Pigs with access to straw spent a significantly greater percentage of

Ž . Ž

observations in straw-directed behaviours than those pigs without straw flatdecks see

.

Table 2 . Pigs in the deep-straw pen spent a significantly greater percentage of all recorded observations in straw-directed behaviour than the pigs in the Straw-Flow pen

ŽP-0.05 , but even a small amount of straw occupied a significant proportion of.

daytime observations.

The percentage of observations spent in pen-directed behaviour was significantly greater by pigs in both flatdecks than those in the straw pens, as was the amount of pig-directed behaviour. In the latter case, there was a tendency for pigs in the large flatdeck to spend a greater percentage of observations in social behaviour than those in

Ž .

either of the straw pens see Table 2 . There were also significant differences between the treatments with regard to nonsocial behaviour. Belly-rooting was not recorded in any treatment during the first week after weaning, but overall tended to be observed more in the large flatdeck than deep straw.

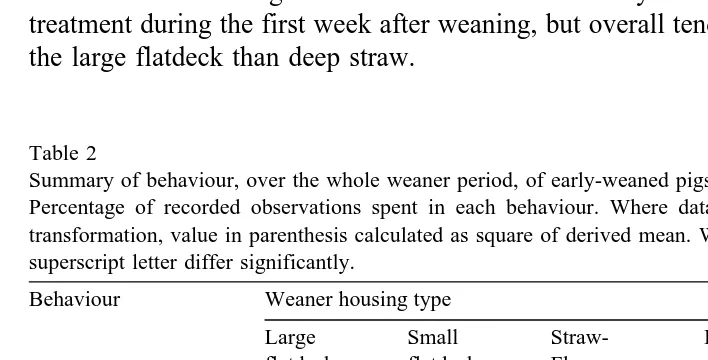

Table 2

Summary of behaviour, over the whole weaner period, of early-weaned pigs reared in different housing types Percentage of recorded observations spent in each behaviour. Where data analysed following square root transformation, value in parenthesis calculated as square of derived mean. Within rows, means with the same superscript letter differ significantly.

Behaviour Weaner housing type

Large Small Straw- Deep s.e.d. p

flatdeck flatdeck Flow straw

a,b c,d Ž .a,c,e Ž .b,d,e

Straw-directed behaviour 0.00 0.00 4.15 17.22 5.30 28.13 0.37 -0.001

a,b c,d a,c b,d

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Pen-directed behaviour 3.59 12.87 3.78 14.27 1.69 2.86 1.32 1.75 0.35 0.001

a,b c,d a,c b,d

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Pig-directed behaviour 3.51 12.29 3.42 11.71 2.58 6.63 2.76 7.61 0.194 0.006

a,b a b

Social behaviour 3.52 2.67 1.52 2.00 0.573 0.057

a,b c,d a,c b,d

Nonsocial behaviour 5.72 6.06 3.20 1.85 0.587 0.001

x x

Belly-rooting 3.23 2.68 1.89 1.21 0.669 0.089

a,b c,d a,c b,d

Nosing any substrate 13.67 12.24 8.26 6.96 0.593 -0.001

a b a,b

Rooting any substrate 8.65 8.53 13.19 19.56 2.780 0.022

a,b c a,d b,c,d

Chew any substrate 3.43 4.05 5.31 8.73 0.628 0.001

Sitting 3.92 3.27 1.47 3.80 1.053 0.177

Inactivity 59.11 55.92 57.36 47.19 4.391 0.123

a c a,c,e c

Sit inactive 1.79 1.77 0.34 1.13 0.285 0.007

a b c a,c,e

Nosing behaviour was more frequent in the flatdecks than in the straw pens. This was not fully accounted for by the higher level of social pig-directed behaviour, indicating that nosing the pen and fittings were important behaviours in these groups. Rooting was observed more frequently in straw pens than in flatdecks. The percentage of observa-tions spent in chewing was greater by pigs in the straw pens than those in the flatdecks, and greater by pigs in deep-straw than those in Straw-Flow. This was a similar pattern to

Ž

straw-directed behaviour. He total amount of substrate directed behaviour pen,

pen-fit-.

ting and pig-directed was higher for the deep straw treatment than for the other three

Ž

treatments 25%, 26%, 27% and 37% of observations for large flatdeck, small flatdeck,

.

Straw-Flow and deep straw respectively . Pigs in deep-straw spent a smaller percentage of observations inactive than those in other treatments, but the difference was not significant. There was less sitting inactive in Straw-Flow than in any other treatment. There was no significant difference between the flatdecks and Straw-Flow with regard to play-behaviour, but there was significantly more play by pigs in the deep-straw pen.

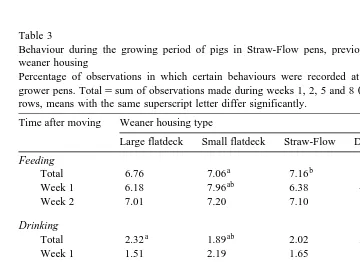

Table 3

Behaviour during the growing period of pigs in Straw-Flow pens, previously reared in different types of weaner housing

Percentage of observations in which certain behaviours were recorded at different times after moving to

Ž .

grower pens. Totalssum of observations made during weeks 1, 2, 5 and 8 see text for more details . Within rows, means with the same superscript letter differ significantly.

Time after moving Weaner housing type

Large flatdeck Small flatdeck Straw-Flow Deep straw s.e.d. p Feeding

a b ab

Total 6.76 7.06 7.16 5.89 0.487 0.071

ab a

Week 1 6.18 7.96 6.38 4.68 0.698 0.090

Week 2 7.01 7.20 7.10 5.23 0.937 0.271

Drinking

a ab b

Total 2.32 1.89 2.02 2.34 0.147 0.005

Week 1 1.51 2.19 1.65 1.69 0.825 0.521

Week 2 2.08 1.25 1.51 2.15 0.659 0.614

Sitting inactiÕe

Total 0.71 0.77 0.59 0.89

a b c abc

Week 1 0.40 0.31 0.19 1.15 0.285 0.072

Week 2 0.49 0.61 0.30 0.39

Rooting

a b c abc

Total 13.72 13.9 12.84 10.50 0.668 0.008

a b ab

Week 1 12.02 14.36 16.03 9.45 1.995 0.054

a b ab

Week 2 20.83 19.64 16.37 13.75 2.005 0.052

Chewing

a b a b

Total 13.62 10.02 11.62 13.39 0.867 0.079

Week 1 14.44 10.43 10.98 11.98 1.612 0.229

3.2. Grower period

Few behaviour categories showed significant differences during the grower period, as shown in Table 3. The percentage of observations spent drinking over the total growingrfinishing period was different between treatments. Pigs from the flatdecks spent a greater percentage of observations rooting in total than those from straw pens, but there was no difference between treatments with regard to straw-directed behaviour

ŽPs0.441 . Pigs from deep-straw pens initially showed a tendency to spend more time.

sitting inactive, but this did not persist.

4. Discussion

4.1. Weaner period

4.1.1. BehaÕioural differences between flatdecks

Space allowance, at the levels examined here, did not appear to have a significant

Ž .

influence on behaviour. Bure 1984 found increased ‘‘abnormal’’ behaviour in small

Ž 2 2 .

flatdecks 0.18 m rpig vs. 0.30 mrpig . However, in the current study, enrichment appeared to have a much larger influence than space.

4.1.2. BehaÕioural differences between straw pens

There was less straw-directed behaviour in the Straw-Flow pen than in the deep-straw pen, and there were also differences in activity, rooting and playing. These results show that only a small amount of straw was required to occupy a significant proportion of time, but the quantity supplied here was not sufficient to provide exactly the same

Ž .

benefits as deep-straw. Arey 1993 also reported a tendency for straw-directed be-haviour to increase with the quantity of straw provided. Pen-directed bebe-haviour and pig-directed behaviour were similar between the two systems, the extra straw-directed behaviour in the deep-straw being accounted for by lower inactivity.

4.1.3. BehaÕioural differences between straw-pens and flatdecks

Only 50 g of straw per pig per day, as was available in Straw-Flow, resulted in large behavioural differences compared to the flatdecks, with regard to straw-directed,

pen-di-Ž .

rected, pig-directed social and nonsocial behaviours, nosing, rooting, chewing, and

Ž .

sitting inactive. Van Putten and Dammers 1976 found time spent rooting to be greater among pigs remaining in a bedded farrowing pen than among those transferred to

Ž .

flatdecks at weaning 46.7% and 21.2% respectively . Supplying ‘‘straw in baskets’’ to

Ž

pigs in slatted pens has also been shown to decrease tail biting Bure and Koomans,

.

1981 . Straw is therefore utilised by pigs as a source of enrichment in a barren environment, serving as a behavioural substrate for a range of different activities. However, it is not practical for use in fully slatted pens because of detrimental effects on liquid manure management. When compost, which did not block the slurry channels, was supplied on a board to pigs in flatdecks, ‘‘abnormal’’ behaviour was decreased

Ž .

important: when pigs in flatdecks were offered ‘‘toys’’ tyre and chains , they occupied only 0.11% of recorded observations, while pigs in a bedded pen spent 5.48% of

Ž .

observations interacting with straw Britton et al., 1993 .

Generally, Straw-Flow shared the behavioural advantages of the deep-straw pen, with

Ž .

fewer potentially damaging to self and others behaviours than the flatdecks examined here. However, the differences in play and other behaviours suggest that deep straw does provide welfare benefits over and above those of Straw-Flow. This supports the health

Ž .

and productivity benefits associated with deep straw reported by Kelly et al. 1998 and

Ž .

Kelly et al. 2000 . Other authors have reported similar behavioural advantages for

Ž

straw-based weaner systems relative to flatdecks for example, Bure, 1984; Sebestik et

.

al., 1984; McKinnon et al., 1989; Schouten, 1991 .

4.2. Grower period

The pigs in Straw-Flow experienced the least change in environment following transfer to the grower pens. There was a greater area per pig, but the same amount of available straw per square metre as in the weaner pens. Straw-Flow was therefore the reference group for this period. Pigs from the deep-straw system experienced less straw than previously and were therefore having to adjust to the ‘‘loss’’, while pigs from the flatdecks gained a solid floor and straw, thus discovering a novel manipulable substrate.

Ž

There were behavioural indications greater time sitting inactive, less straw-directed

.

behaviour in the first week following transfer to the grower pens that the pigs from the deep straw pen were relatively ‘‘deprived’’ of straw. However, these tendencies did not

Ž .

persist. Boe 1993 found that straw-directed behaviour was increased during the growing period among pigs weaned into flatdecks compared with those from bedded pens. This was not the case in this study, although total time spent rooting did show significant differences related to previous housing treatments. The frequency of

straw-di-Ž .

rected behaviour during the grower phase was similar to that reported by Pearce 1993 , who found that growing pigs on Straw-Flow spent 24.63% of observations in

straw-di-Ž . Ž .

rected behaviour. Sachsenmaier 1984 reported more dog-sitting sitting inactive , suckling and restlessness when pigs were transferred from enriched to barren pens. In this trial, pigs from the flatdecks seemed to be taking advantage of the available straw, while pigs from deep-straw took time to adjust to ‘‘less-enriched’’ housing. The most dramatic effects of early experience reported in the literature relate to loss of enrichment

Ži.e. moving from bedded to barren housing , and did not involve commercial systems..

Instead, large and complex housing was compared with fully slatted fattening pens

ŽBeattie et al., 1993 . It is therefore suggested that since the Straw-Flow grower pens in.

the present study were not an extreme environment, residual weaner-treatment effects were not observed. A cross-over study involving pigs from each weaner house being transferred to either barren or enriched housing might reveal stronger differences.

5. Conclusions

In the weaner period, the presence of straw led to fewer potentially damaging

Ž .

some behavioural differences between deep-straw and Straw-Flow which indicated a

Ž .

welfare advantage to the former such as increased straw-directed and play behaviour . Increased floor area per pig in flatdecks did not lead to behavioural changes likely to benefit welfare. Thus, provision of bedding is recommended for early-weaned pigs, but this study demonstrates that only a small quantity of straw is required to provide welfare benefits. The residual effects of early experience as observed in this trial were minimal. Some behavioural differences were observed in the early grower period during the process of adaptation, but these did not persist. Taking these results in conjunction with results from other nonbehavioural studies, it is concluded that the Straw-Flow system can provide suitable accommodation for weaned pigs.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to J. MacDonald, S. Philips for technical support. HRCK was supported by the Cruden Foundation; SAC receives financial support from SOAEFD.

References

Arey, D.S., 1993. Effect of straw on the behaviour and performance of growing pigs in Straw-Floww pens. Farm Buildings Prog. 112, 24–25.

Banks, E.M., 1982. Behavioural research to answer questions about animal welfare. J. Anim. Sci. 54, 434–446.

Beattie, V.E., Sneddon, I.A., Walker, N., 1993. Behaviour and productivity of the domestic pig in barren and enriched environments. In: Livestock Environment IV, Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium, American Society of Agricultural Engineers, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK. pp. 43–50. Boe, K., 1993. The effect of age at weaning and post-weaning environment on the behaviour of pigs. Acta

Agric. Scand., Sect. A 43, 173–180.

Britton, M., Roden, J.A., MacPherson, O., Wilcox, G., English, P.R., 1993. A comparison of a straw-based and slatted floor housing system for the weaned pig. In: Proc. British Society of Animal Production Winter Meeting.

Ž .

Broom, D.M., 1989. Ethical dilemmas in animal usage. In: Paterson, D., Palmer, M. Eds. , The Status of Animals: Ethics Education and Welfare. C.A.B. International, Wallingford, UK, pp. 80–86.

Bruce, J.M., 1990. Straw-Flow: a high welfare system for pigs. Farm Building Prog. 102, 9–13.

Bruce, J.M., Clark, J.J., 1979. Models of heat production and critical temperature for growing pigs. Anim. Prod. 28, 353–369.

Bure, R.G., 1984. The influence of housing conditions on social behaviour in pigs. In: Unshelm, J., van Putten,

Ž .

G., Zeeb, K. Eds. , Applied Ethology in Farm Animals, Proceedings of the International Conference, Kiel. pp. 159–161.

w

Bure, R.G., Koomans, P., 1981. Welzijn en huisvesting van gespeende biggen en mestvarkens. Well-being x

and housing of weaners and fattening pigs Publikatie-IMAG 155, 57–60.

Bure, R.G., van de Kerk, P., Koomans, P., 1983. Het verstrekken van stro, compost en tuinaarde aan

Ž .

mestvarkens The supply of straw, compost and garden mould to fattening pigs . Inst V. Mech. Arbeid en Gebouwen, Wageningen, Netherlands.

Dawkins, M.S., 1980. Animal Suffering. Chapman & Hall, London, UK.

Dybkjaer, L., 1992. The identification of behavioural indicators of ‘‘stress’’ in early-weaned piglets. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 35, 135–147.

Kelly, H.R.C., Bruce, J.M., Edwards, S.A., English, P.R., Fowler, V.R., 1998. Air quality in different housing systems for early-weaned pigs. In: Proc. 15th International Pig Veterinary Society Congress Birmingham, UK vol. 3 p. 12.

Kelly, H.R.C., Bruce, J.M., Edwards, S.A., English, P.R., Fowler, V.R., 2000. Limb injuries, immune response and growth performance of early-weaned pigs in different housing systems. Anim. Sci. 70, 73–83.

Lyons, C.A.P., Bruce, J.M., Fowler, V.R., English, P.R., 1995. A comparison of productivity and welfare of growing pigs in four intensive systems. Livest. Prod. Sci. 43, 265–274.

McKinnon, A.J., Edwards, S.A., Stephens, D.B., Walters, D.E., 1989. Behaviour of groups of weaner pigs in three different housing systems. Br. Vet. J. 145, 367–372.

Pearce, C.A., 1993. Behaviour and other indices of welfare in growingrfinishing pigs kept on Straw-Floww

, bare concrete, full slats and deep straw. PhD thesis, University of Aberdeen.1993

Sachsenmaier, M.M., 1984. Untersuchungen uber den Einfluss Verschiedener Saugezeiten und Haltungsfor-men auf das Verhalten von Ferkeln bis zum Alter von driel Monaten. Inaugural dissertation, Justus-Leibig Universitat, Geisson, pp. 80–81.

Schouten, W.G.P., 1991. Effects of rearing on subsequent performance in pigs. Pig News Inf. 12, 245–247. Sebestik, V.K., Bogner, H., Fusseder, J., Grauvogl, A., Sprengel, D., 1984. Ethologishe und Productionstech-nische Untersuchungen an Abgesetzen Ferkeln in drei unterschiedlichen Haltungssystemen. Bayer. Land-wirtsch. Jahrb. 61, 865–893.

Silver, C.L., 1989. Assessment of pig keeping systems. Pig Vet. J. 23, 83–107.