www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Play behaviour in group-housed dairy calves, the

effect of space allowance

Margit Bak Jensen

a,), Rikke Kyhn

b,1a

Department of Animal Health and Welfare, Danish Institute of Agricultural Sciences, Research Centre Foulum, Tjele, Denmark

b

Department of Animal Science and Animal Health, The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural UniÕersity,

Copenhagen, Denmark

Accepted 14 October 1999

Abstract

In dairy calves kept in pens, lack of sufficient space may inhibit the performance of play behaviour. The present study investigated, firstly, if an increase in space allowance increases the occurrence of play behaviour, and secondly, if calves kept at a low space allowance perform more locomotor play when released individually in a large novel area. A total of 96 dairy calves in six repetitions were housed in groups of four, in pens of either 4, 3, 2.2 or 1.5 m2 per calf from 2

weeks of age. The occurrence of play behaviour in the home environment was recorded continuously for each individual calf during 24 h at 5, 7 and 9 weeks of age. Locomotor play

Ž

decreased over the weeks 54, 29 and 19 s for weeks 5, 7 and 9, respectively; F2,40s17.98;

.

P-0.001 , and the interaction between space allowance and week tended to be significant

ŽF s1.96; P . 2

-0.10 . At 5 weeks of age, calves kept at 4 or 3 m per calf performed more

6,40

2 Ž

locomotor play in the home environment than calves at 2.2 or 1.5 m per calf 68, 74, 38 and 39 s

2 .

for 4, 3, 2.2 and 1.5 m per calf, respectively; F3,15s3.40; P-0.05 , but in weeks 7 and 9, no effects of space allowance were found. In addition, the duration of locomotor play was recorded for all calves during an individual 10-min open-field test in a 9.6=4.8 m arena at 4 and 10 weeks of age. During the open-field test at 10 weeks of age, calves from pens with 1.5 m2 per calf

Ž

performed more locomotor play than calves on the remaining treatments 10, 9, 12 and 25 s for 4,

2 .

3, 2.2 and 1.5 m per calf, respectively; F3,15s4.05; P-0.05 . The present study shows that an

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q45-8999-1325; fax:q45-8999-1500.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] M.B. Jensen .

1 ˚

Present address: Landbogarden, Peberlyk 2, DK-6200 Abenra.˚ ˚

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Ž .

increase in the available space increases the occurrence of locomotor play in the home environ-ment at 5 weeks of age. It also shows that calves kept in pens with the smallest space allowance performed more locomotor play behaviour when released in a large arena at 10 weeks of age.

q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Play behaviour; Cattle; Open-field test; Space allowance; Welfare

1. Introduction

In the assessment of animal welfare, the focus has been on indicators of negative feelings and poor welfare. However, the absence of negative feelings does not automati-cally ensure positive feelings, and it is relevant to find and use indicators of positive feelings and good welfare. Juveniles play when their primary needs are met and the performance of play behaviour appears to be reinforcing. Play behaviour has been

Ž

suggested to be an indicator of good welfare in wild as well as captive juveniles Fagen,

.

1981; Lawrence, 1987 , and has been used to assess welfare in different farm

environ-Ž .

ments e.g., Dannenman et al., 1985; Blackshaw et al., 1997 .

Under natural or semi-natural conditions, play in calves is typically seen in a social

Ž .

context either as locomotor play or play fighting Reinhardt, 1980 . Locomotor play includes vigorous jumping, kicking, and running, often interrupted by fast stops and turns in a new direction. Locomotor play is typically performed by several calves at the

Ž .

same time parallel play , but it does not involve physical contact. Play fighting involves two or more individuals facing each other, pushing and bunting each other. Invitation to play fight may be seen as approach and rotations of the head. Play fighting is often interrupted by parallel locomotor play, and unlike serious fights, play fighting is

Ž

terminated without submission, flight or chase Reinhardt and Reinhardt, 1982; Vitale et

. Ž

al., 1986 . Another type of social play is playful mounting Reinhardt et al., 1978; Vitale

.

et al., 1986 . Finally, play behaviour in calves also includes bunting and pushing objects

ŽBrownlee, 1954 , as well as ground play, where the calf rubs its neck and head against.

Ž .

the ground while kneeling down Schloeth, 1961 .

Increasing the space allowance from 1.4 m2 per calf to 4 m2 per calf increased the Ž

occurrence of locomotor play in 4–6-week old calves kept indoors in group pens Jensen

. 2

et al., 1998 . The minimum requirements according to EU legislation are 1.5 m per calf

ŽAnonymous, 1993, 1997 and a space allowance of 4 m. 2 per calf is a lot more than

that. Therefore, it would be relevant to investigate whether space allowances between these two extremes affect the calves’ performance of play behaviour.

More running, bucking and kicking has been observed in calves from small individ-ual pens when released in a large area compared to calves from large group pens

ŽDellmeier et al., 1985 , or large individual pens De Passille and Rushen, 1995; Jensen,. Ž

´

.The present study investigated, firstly, how four different space allowances between 1.5 and 4 m2 per calf affect the occurrence of play behaviour in calves, and secondly, if

Ž

calves kept at low space allowances perform more locomotor activities identical to

.

locomotor play when released individually in a large open-field test arena.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals, housing and feeding

A total of 96 Danish Holstein Friesian male and female calves were separated from

Ž .

their dams at birth, and housed individually in straw-bedded pens 0.95=1.95 m . Calves were grouped according to birth order and sex, into six repetitions of 16 calves. When the youngest calf in a particular repetition was 7 days old, all calves in this repetition were moved to the experimental barn. Here the calves of each sex were allocated at random to one of four groups, each containing four calves, i.e., the sex ratio

Ž

was the same in the four groups within repetition either three males and one female,

.

two males and two females, or one male and three females . In total, there were 48 male and 48 female calves in the experiment. The four groups were housed in one of four pen

2 Ž . 2 Ž . 2

types at either 1.5 m per calf 2.40=2.54 m , 2.2 m per calf 3.00=2.90 m , 3.0 m

Ž . 2 Ž .

per calf 3.50=3.50 m , or 4.0 m per calf 3.90=4.20 m . All pens were straw-be-dded. Partitions between neighbouring pens were 1.2 m high — the bottom 0.5 m was solid, and the top 0.7 m was made from tubular metal bars.

When the calves were moved to the experimental barn, they were, on the average, 16

ŽS.D.s6 days old and weighed 52 S.D.. Ž s7 kg. At the end of the experiment, the.

Ž .

calves weighed 107 S.D.s16 kg.

All calves were offered their dam’s colostrum ad libitum for the first 4 days of life. From the fifth day and until the calves were, on the average, 6 weeks of age, the calves in the repetition were offered 3 l of whole milk twice a day from a bucket. From an average age of 6 weeks and until weaning at an average age of 8 weeks, the calves were offered 1.5 l of milk twice a day. All calves were offered concentrates and hay ad libitum.

2.2. ObserÕations in the home enÕironment

Ž .

The behaviour of the calves was video recorded for 24 h 1 day when the calves were on average 5, 7 and 9 weeks old, that is, once while they were fed 6 l of milk per day, once while they were fed 3 l of milk per day and once after weaning. Data on play behaviour for each individual were recorded continuously for all hours of observation

Žbehaviour sampling . Play behaviour was categorised as locomotor play, social play,. Ž

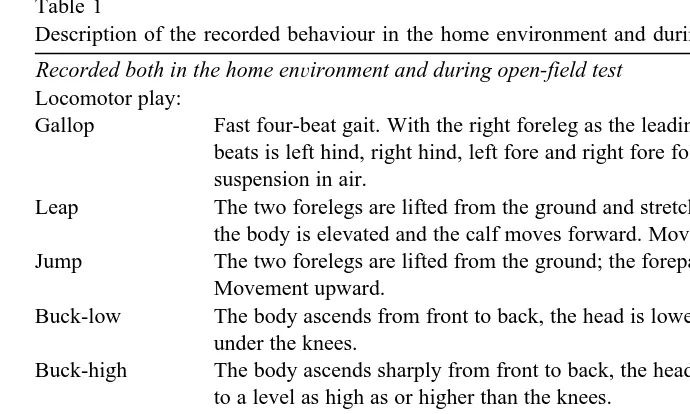

object play, or ground play. The recorded behaviours are described in Table 1 see

.

Table 1

Description of the recorded behaviour in the home environment and during open-field tests

Recorded both in the home enÕironment and during open-field test

Locomotor play:

Gallop Fast four-beat gait. With the right foreleg as the leading leg, the sequence of hoof beats is left hind, right hind, left fore and right fore followed by a phase of suspension in air.

Leap The two forelegs are lifted from the ground and stretched forward, the forepart of the body is elevated and the calf moves forward. Movement upward and forward. Jump The two forelegs are lifted from the ground; the forepart of the body is elevated.

Movement upward.

Buck-low The body ascends from front to back, the head is lowered, hoofs are lifted to a level under the knees.

Buck-high The body ascends sharply from front to back, the head is lowered, hoofs are lifted to a level as high as or higher than the knees.

Buck-kick The body ascends sharply from front to back, the head is lowered, hoofs are raised to a level as high as or higher than the knees and one or both hind legs are kicked in a posterior direction.

Turn The two forelegs are lifted from the ground and stretched forward, as the forepart of the body is elevated and turned to one side, the calf moves sideward. Movement upward and sideward.

Head-shake The head is shaken or rotated.

Recorded only in the home enÕironment

Social play:

Play fight Two calves are standing front to front, butting head against headrneck in a playful manner.

Mount A calf mounts another calf’s head or body from front, side, or back. Object play:

But fixtures Butting water bowl, hayrack or bars in a playful manner, standing up. Ground play:

But or rub straw Butting straw or rubbing head and neck in straw in a playful manner, kneeling down on the two forelegs.

Recorded only during open-field test

Walk A four beat gait. Sequence of hoof beats is left hind, left fore, right hind and right fore. Two or three hoofs touch the ground at any time

Trot A two beat gait with leg movements synchronised diagonally. The sequence of hoof beats is left hind together with right fore, followed by right hind and left fore Sniff Sniffing the floor or the wall of the arena

to calculate time spent active. Calves showing clinical signs of pneumonia on the day of

Ž

observation were not observed two calves in week 5, six calves in week 7, and eight

.

calves in week 9 .

2.3. Open-field tests

between 0800 and 1400 h in an open-field test arena placed in a barn adjacent to the barn in which the calves were housed. The arena measured 4.8=9.6 m and had 2 m high sides made of plywood. The floor of the arena was covered with a layer of 10 cm sand mixed with fibres of fibreglass to make the sand firm. A start box was placed at one end of the arena and a video camera, placed above the arena, recorded the behaviour during the test. The calves were led individually by a halter from their home pen to the start box and left undisturbed there for 1 min. While being led, the calves were only allowed to walk quietly and not allowed to run. The door from the start box to the arena was opened and the calf was left undisturbed for another minute. Calves that did not enter within this minute were gently pushed into the arena. After the calf had entered the arena, the duration of the test was 10 min. The duration of walk, trot, gallop, leap, jump, buck and buck-kick were recorded continuously on video. The duration of sniffing the walls or the floor of the arena was also recorded continuously. Calves showing clinical

Ž

signs of pneumonia on the day of testing were not tested seven calves at 4 weeks and

.

eight calves at 10 weeks of age .

2.4. Statistical analyses of data from the home enÕironment

For each individual calf, the duration of locomotor play and play fighting as well as

Ž .

time spent active not lying down were calculated separately for each of the three observations. The duration of locomotor play, play fighting and time spent active were calculated and transformed to logarithmic values to remove skewness from the data. To assess if the space allowance affected the quality of locomotor play, the duration of

Ž .

those elements requiring most space gallop, leap, buck-kick and buck-high was calculated as a percentage of the total duration of locomotor play. These values were then transformed by taking the square root, to remove skewness from the data before analysis. As a measure of the synchrony of locomotor play in the pens, the time where two or more calves in a pen were performing locomotor play at the same time was calculated as a percentage of the time where at least one calf in the pen was performing locomotor play. This percentage was also square-root transformed before analysis. To model the correlation in the data correctly, all the above-mentioned variables were

Ž .

analysed using the mixed model MIXED procedure of Statistical Analysis System

ŽSAS Institute, 1990; Littell et al., 1996 . The first model included as fixed effects space.

allowance, sex, week, as well as the interaction between space allowance and week, and the interaction between sex and week. Repetition, the interaction between repetition and space allowance, and the interaction between repetition, space allowance, and week were included as random effects. Values for the different levels of space allowance and week were contrasted if significant effects of space allowance or week were to be found. If interactions between week and space allowance or between week and sex were

Ž .

was balanced within repetition, the effect of sex and the interaction between sex and week could only be tested without taking into account the dependence between calves in the same pen, as these effects were tested against the residual error.

Not all calves performed object play, ground play, or mounting and these variables were transformed into binary data. The effects of space allowance and sex on the number of calves performing object play, ground play, and mounting were analysed by Chi-square analysis, while the effects of week on these variables were analysed using

Ž .

the Cochran Q-test Siegel and Castellan, 1988 .

2.5. Statistical analysis of data from the open-field tests

Within each of the two open-field tests, data for the duration of galloping, leaping, jumping, buck-low, buck-high, buck-kicking, turning and head shaking were grouped as locomotor play. During the first open-field test, a large number of the calves were not observed performing locomotor play or trotting, and data for these variables were transformed into binary data and analysed by Chi-square analysis. During the second open-field test, data for the duration of locomotor play were transformed by taking the square root, while the data for the duration of trotting were transformed by taking the logarithm, and were then analysed using a mixed model. The duration of walking and the duration of sniffing the arena during each of the two tests were transformed by taking the logarithm and were also analysed using a mixed model. The mixed model included space allowance, sex and their interaction as fixed affects, while repetition, the interactions between repetition and space allowance, and the interaction between repeti-tion and sex, were included as random effects. As calves were tested individually, the effect of sex could be tested by an F-test using the interaction between sex and repetition as error term, taking into account the dependence between calves of the same sex in the same repetition.

3. Results

3.1. BehaÕiour in the home enÕironment

Ž .

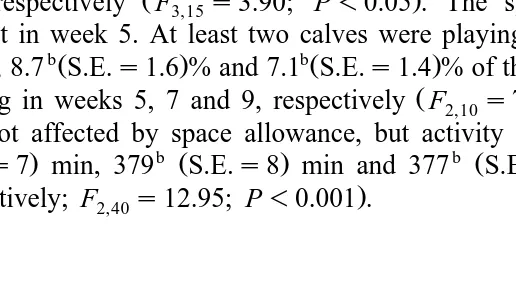

Locomotor play decreased over the weeks F2,40s17.98; P-0.001; Fig. 1 , and the interaction between space allowance and weeks tend to be significant for locomotor play

ŽF6,40s1.96; P-0.10 . This was due to an effect of space allowance at 5 weeks of.

age, where calves kept at 4 or 3 m2 per calf performed more locomotor play than calves

2 Ž .

kept at 2.2 or 1.5 m per calf F3,15s3.40; P-0.05; Fig. 2 . In weeks 7 and 9, locomotor play was not affected by space allowance. No effect of week was found for

Ž .

play fighting Fig. 1 , but there tend to be an interaction between sex and week

ŽF2,197s2.66; P-0.10 as male calves performed more play fighting than female.

Ž Ž . Ž . .

calves in week 7 196 S.E.s28 s vs. 142 S.E.s24 s; F1,65s4.22; P-0.05 . The

Ž

duration of those elements of locomotor play requiring much space gallop, leap,

.

buck-kick, buck-high relative to the total duration of locomotor play, was neither

Ž .

Fig. 1. The duration of play fighting and locomotor play, respectively, at 5, 7 and 9 weeks of age. Means and standard errors are given. Within type of play, means with different superscripts are different at P-0.05.

allowance were found on the overall synchrony of locomotor play. In the pens with the smallest space allowance, locomotor play was less synchronised. At least two calves

a Ž . a Ž . a Ž .

played at the same time in 12.4 S.E.s1.4 %, 11.5 S.E.s1.7 %, 9.9 S.E.s1.9 %

bŽ . 2

and 6.3 S.E.s1.4 % of time where at least one calf played at 4, 3, 2.2 and 1.5 m per

Ž .

calf, respectively F3,15s3.90; P-0.05 . The synchrony of locomotor play was

aŽ

highest in week 5. At least two calves were playing at the same time in 14.9 S.E.s . bŽ . bŽ .

2.1 %, 8.7 S.E.s1.6 % and 7.1 S.E.s1.4 % of the time where at least one calf were

Ž .

playing in weeks 5, 7 and 9, respectively F2,10s7.08; P-0.01 . Time spent active

Ž a

was not affected by space allowance, but activity increased from week 5 to 7 341

ŽS.E.s7 min, 379. b ŽS.E.s8 min and 377. b ŽS.E.s8 min for weeks 5, 7 and 9,. .

respectively; F2,40s12.95; P-0.001 .

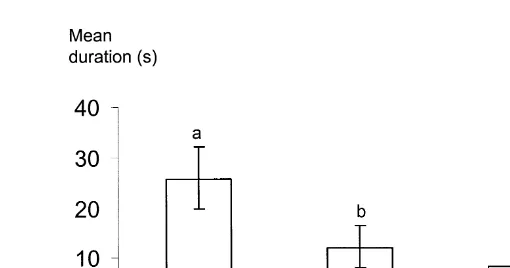

Fig. 3. The duration of locomotor play in calves kept at 1.5, 2.2, 3.0 or 4.0 m2per calf during open-field tests at 10 weeks of age. Means and standard errors are given. Means with different superscripts are different at

P-0.05.

3.2. BehaÕiour during open-field tests

In week 4, no differences between treatments were found for the duration of walking

Žmeans163 s , the number of calves trotting 60% or for the number of calves. Ž . Ž .

performing locomotor play 60% . The duration of sniffing the arena during this first open-field test was not affected by space allowance, but male calves sniffed the arena

Ž Ž . Ž . .

more than female calves 234 S.E.s22 s vs. 180 S.E.s17 s; F1,5s8.48; P-0.05 . During the open-field test at 10 weeks of age, calves from the pens with 1.5 m2 per calf

Ž

performed more locomotor play than calves on the other three treatments F3,15s4.05;

.

P-0.05; Fig. 3 , but there were no differences between the treatments or sexes with

Ž . Ž .

respect to the duration of walking means161 s , trotting means12 s or the duration

Ž .

of sniffing the arena means182 s during this open-field test.

4. Discussion

The present study shows that an increase in the space allowance above minimum EU

Ž .

requirements Anonymous, 1993, 1997 increases the occurrence of locomotor play at 5 weeks, but not at 7 and 9 weeks of age. However, during release in a large arena at 10 weeks of age, calves from the smallest pens had a greater motivation to perform locomotor activities, which are identical in structure to the activities categorised as locomotor play in the home environment.

prevent the calves from performing it simultaneously. Early on, when the level of locomotor play was high, prevention from synchronous locomotor play in the smallest pens may have suppressed the level of the behaviour.

In this study, where a group size of four was used, an increase in space allowance from 1.5 to 3 m2 per calf increased locomotor play significantly, while no additional

effect was found when increasing space allowance further to 4 m2 per calf. There are

two aspects of space for group-housed calves: space allowance per animal and total space available in the pen. For larger group sizes, more shared space is available in the pen at a given space allowance per animal, and the effect of space allowance per animal has to be considered in relation to group size.

The level of locomotor play as well as the synchrony of locomotor play decreased over the weeks. However, the quality of locomotor play was not affected by week. Therefore, it seems unlikely that the dimensions of all the pens limited the expression of locomotor play in later weeks. The decrease in locomotor play over weeks is more likely to reflect a general effect of age and an effect of the gradual weaning. In pigs, a decline

Ž .

in locomotor play concurred with weaning Newberry et al., 1988 and in deer, a

Ž

decrease in milk supply decreased the level of locomotor play Muller-Schwarze et al.,

¨

.1982 . However, it has also been reported in pronghorn that locomotor play may

Ž

increase again after weaning as the animals increase their intake of solid food Miller

.

and Byers, 1991 . In the present experiment, the calves were weaned of milk gradually to allow them to increase their intake of solid food before milk was removed altogether. Obviously, this weaning was confounded with age of the animals and these two factors cannot be considered separately in this study.

The level of play fighting did not decrease over the weeks, as the level of locomotor play did. However, differences in the timing of these two types of play behaviour have been described earlier. Locomotor play was observed during the first week of the calves’

Ž .

lives Wood-Gush et al., 1984 , while calves were observed to start play fighting in their

Ž .

second week of life Reinhardt and Reinhardt, 1982; Wood-Gush et al., 1984 . Differ-ences in the timing of the two types of play have also been described in Cuvier’s Gazelle where locomotor play was at its highest at 2 weeks of age and declined

Ž

thereafter, while play fighting increased from 2 weeks to 6 months of age Gomendio,

.

1988 . Therefore, the time trends of the two types of play at the ages studied here are not in conflict with other studies on ungulates.

Ž

Males solicited more play fighting than female calves in Maremma cattle Vitale et

.

al., 1986 , and in other species of ungulates, males have also been reported to perform

Ž

more social play than females, for instance in sheep Sachs and Harris, 1978; Berger,

. Ž . Ž .

1979 , Siberian ibex Byers, 1980 , Cuvier’s gazelle Gomendio, 1988 , and swine

ŽDobao et al., 1985 . Sachs and Harris 1978 reported that female lambs performed. Ž .

more locomotor play than male lambs, but no sex differences were found in locomotor

Ž . Ž .

play in gazelle Gomendio, 1988 , or swine Newberry et al., 1988 . The present study indicates that male dairy calves may be more involved in play fighting than female calves.

the reason why play fighting was not influenced by the space allowances used in this study. It is also possible that play fighting is less sensitive to the quality of the external environment than locomotor play, in which case the two different types of play may relate differently to welfare.

The elements categorised as locomotor play in the home environment were also observed during open-field tests, and were categorised as play in both situations.

During the open-field test at 4 weeks of age, not all calves were observed performing locomotor play. As the level of locomotor play in the home environment was high at 5 weeks of age, more activity during the open-field test could have been expected. The low level of locomotor play during this first test might be explained by more fear the first time the calves were introduced into the arena as fear may cause inactivity and

Ž .

behavioural inhibition Boissy and Bouissou, 1995 . Young calves may also be more reluctant to move in a novel environment, as younger calves have earlier been reported

Ž .

to run and buck less during open-field tests than older calves De Passille et al., 1995 .

´

At 10 weeks of age, there was an effect of space allowance on the level of locomotor play during the open-field test although at this age, the level of locomotor play in the home environment was low. Calves from pens with the smallest space allowance showed a significantly higher motivation to perform locomotor play than calves on the other three treatments during this second open-field test. Other studies have shown that calves kept in small pens performed more of these vigorous locomotor activities during

Ž

open-field tests than calves kept in more spacious environments Dellmeier et al., 1985;

.

Miller et al., 1986; Jensen et al., 1999 . In these experiments, the treatments differed with respect to the level of social contact in addition to space allowance, but more locomotor activity during open-field tests has also been found in calves kept in small

Ž

individual pens than in calves kept in similar but larger individual pens De Passille and

´

.Rushen, 1995; Jensen, 1999 , which supports that space allowance is the important factor. The results of the present study show that the effect of space allowance on the level of vigorous locomotor activities during open-field tests also applies to group-housed calves, having more shared space than the calves kept in individual pens.

The question of what motivates the vigorous locomotor activities, or locomotor play, during an open-field test has been subject to some controversy. The increased level of galloping, bucking and buck-kicking during open-field tests of confined calves com-pared to calves kept in pens with a higher space allowance has been suggested to be due

Ž

to an increased internal buildup of motivation to perform these behaviours Dellmeier et

.

al., 1985 , and the activity has also been suggested to be elicited by the mere release in a

Ž .

novel environment De Passille et al., 1995 . It seems plausible that both internal and

´

external factors may stimulate locomotor play. The release in a spacious arena may have stimulated locomotor play in all calves. However, the higher level of locomotor play in calves housed in the smallest pens is likely to reflect a larger motivation to perform locomotor play due to a greater buildup of internal motivation to do so while these calves are housed with little space in their home environment. Increased motivation to play after periods, where play has been suppressed or absent due to adverse

environmen-Ž

tal conditions has earlier been reported in wild monkeys Sommer and

Mendoza-.

Granados, 1995 , and in the domestic dog, a low level of play early in life was

Ž .

On the other hand, in the present experiment an effect of space allowance in the home environment was only found in week 5 and not in week 9, the week before the second open-field test, which would have supported the hypothesis that the higher motivation to play during an open-field test is due to suppression of play during housing in small pens. Therefore, more knowledge is needed of the motivation to perform locomotor play.

The observed level of play behaviour in the present experiment was quite low, only about 0.2% of the total time or about 1% of the active time. In pronghorn, juveniles have

Ž .

been reported to play for 1–2% of their time Miller and Byers, 1991 and in vicuna,

Ž .

levels of less than 1% of the time have been reported Vila, 1994 . However, the fact

Ž

that play occupies little time does not mean that it is not important to the animal Bekoff

.

and Byers, 1992 . Environmental change has been reported to elicit play behaviour in

Ž .

piglets Newberry et al., 1988 and a higher level of play behaviour may have been seen if straw had been supplied more often or if novel objects had been provided.

In summary, an effect of space allowance on early locomotor play was found in calves kept in groups. Under the hypothesis that performance of play is associated with positive feelings, increasing space above the minimum requirements of 1.5 m2 per calf to 3.0 m2 per calf in pens with four calves is of significance to the welfare of the animals. However, the space allowance has to be considered in relation to group size, because keeping calves in larger groups may give a better opportunity to play. The higher motivation to perform locomotor play during the open-field test of the calves kept in the smallest pen type illustrates that the effects of confinement on locomotor play activity during open-field tests also apply to group-housed calves.

Acknowledgements

The study was recommended by The Nordic Joint Committee for Agricultural Research and founded by the Danish Ministry of Food, Agriculture, and Fisheries. We thank Gynther Nielsen and Erik L. Decker for their technical assistance. We also thank Karin Hjelholt Jensen, Lene Munksgaard, Steffen W. Hansen, and two anonymous referees for valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper.

References

Anonymous, 1993. Regulation No. 999 on protection of calves. Danish Ministry of Justice. 14th December 1993, 3 pp.

Anonymous, 1997. Regulation No. 1075 on change of regulation on protection of calves. Danish Ministry of Justice. 22nd November 1997, 2 pp.

Bekoff, M., Byers, J.A., 1992. Time, energy and play. Anim. Behav. 44, 981–982.

Berger, J., 1979. Social ontogeny and behavioural diversity: consequences for Bighorn sheep OÕis canadensis

Ž .

inhabiting desert and mountain environments. J. Zool. London 188, 251–266.

Blackshaw, J.K., Swain, A.J., Blackshaw, A.W., Thomas, F.J.M., Gillies, K.J., 1997. The development of playful behaviour in piglets from birth to weaning in three farrowing environments. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 55, 37–49.

Boissy, A., Bouissou, M.F., 1995. Assessment of individual differences in behavioural reactions of heifers exposed to various fear-eliciting situations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 46, 17–31.

Byers, J.A., 1980. Play partner preferences in Siberian Ibex, Capra ibex sibirica. Z. Tierpsychol. 53, 23–40. Dannenman, K., Buchenauer, D., Fliegner, H., 1985. The behaviour of calves under four levels of lighting.

Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 13, 243–258.

Dellmeier, G.R., Friend, T.H., Gbur, E.E., 1985. Comparison of four methods of calf confinement: II. Behaviour. J. Anim. Sci. 60, 1102–1109.

De Passille, A.M., Rushen, J., 1995. Effects of spatial restriction and behavioural deprivation on open-field´

responses, growth and adrenocortical reactivity of calves. In: Rutter, S.M., Rushen, J., Randle, H.D.,

Ž .

Eddison, J.C. Eds. , Proc. 29th Int. Congr. Int. Soc. Appl. Ethol.. Exeter, UK, p. 207, UFAW, Potters Bar. De Passille, A.M., Rushen, J., Martin, F., 1995. Interpreting the behaviour of calves in an open field test: a´

factor analysis. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 45, 201–213.

Dobao, M.T., Rodriganez, J., Silio, L., 1985. Choice of companion in social play in piglets. Appl. Anim.˜ ´

Behav. Sci. 13, 259–266.

Fagen, R.M., 1981. Animal Play Behaviour. Oxford University Press, New York, 684 pp.

Gomendio, M., 1988. The development of different types of play in gazelles: implications for the nature and functions of play. Anim. Behav. 36, 825–836.

Jensen, M.B., 1999. Effects of confinement on rebounds of locomotor behaviour of calves and heifers, and the spatial preferences of calves. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 62, 43–56.

Jensen, M.B., Munksgaard, L., Mogensen, L., Krohn, C., 1999. Effects of housing in different social environments on open-field responses and social responses of female dairy calves. Acta Agric. Scand., Sect. A 49, 113–120.

Jensen, M.B., Vestergaard, K.S., Krohn, C.C., 1998. Play behaviour in domestic calves kept in pens: the effect of social contact and space allowance. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 56, 97–108.

Lawrence, A., 1987. Consumer demand theory and the assessment of animal welfare. Anim. Behav. 35, 293–295.

Littell, R.C., Milliken, G.A., Stroup, W.W., Wolfinger, R.D., 1996. SAS System for Mixed Models. SAS Institute, Cary, NC, 633 pp.

Ž

Lund, J.D., Vestergaard, K.S., 1998. Development of social behaviour in four litters of dogs Canis .

familiaris . Acta Vet. Scand. 39, 183–193.

Miller, C.P., Wood-Gush, D.G.M., Martin, P., 1986. The effect of rearing system on the responses of calves to novelty. Biol. Behav. 11, 50–60.

Miller, M.N., Byers, J.A., 1991. Energetic cost of locomotor play in pronghorn fawns. Anim. Behav. 41, 1007–1013.

Muller-Schwarze, D., Stagge, B., Muller-Schwarze, C., 1982. Play behaviour: persistence, decrease, and¨

energetic compensation during food shortage in deer fawns. Science 215, 85–87.

Newberry, R.C., Wood-Gush, D.G.M., Hall, J.W., 1988. Playful behaviour of piglets. Behav. Processes 17, 205–216.

Reinhardt, 1980. Untersuchung zum Socialverhalten des Rindes. Birkhauser, Basel.¨

Reinhardt, V., Mutiso, F.M., Reinhardt, A., 1978. Social behaviour and social relationships between female and male prepubertal bovine calves. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 4, 43–54.

Reinhardt, V., Reinhardt, A., 1982. Mock fighting in cattle. Behaviour 81, 1–13.

Sachs, B.D., Harris, V.S., 1978. Sex differences and developmental changes in selected juvenile activities

Žplay of domestic lambs. Anim. Behav. 26, 678–684..

SAS Institute, 1990. In: SAS Users Guide: Statistics Version 6. 4th edn. Statistical Analysis Systems Institute, Cary, NC, 1686 pp.

Schloeth, R., 1961. Das Socialleben des Carmargue Rindes. Z. Tierpsychol. 18, 574–627.

Siegel, S., Castellan, N.J., 1988. Nonparametric Statistics for the Behavioural Sciences. 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill, NY.

Sommer, V., Mendoza-Granados, D., 1995. Play as indicator of habitat quality: a field study of langur

Ž .

monkeys Presbytis entellus . Ethology 99, 177–192.

Vila, B.L., 1994. Aspects of play behaviour of vicuna, VicugnaÕicugna. Small Rumin. Res. 14, 245–248.

Vitale, A.F., Tenucci, M., Papini, M., Lovari, S., 1986. Social behaviour of the calves of semi-wild Maremma cattle, Bos primigenius taurus. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 16, 217–231.