www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

Effects of handling aids on calf behavior

Candace C. Croney

), Lowell L. Wilson, Stanley E. Curtis,

Erskine H. Cash

Dairy and Animal Science Department, The PennsylÕania State UniÕersity 324 William L. Henning Building,

UniÕersity park, PA 16802 USA

Accepted 17 March 2000

Abstract

Effects of three different handling aids on calf behavior were determined. Group 1 calves were

Ž .

intensively-reared intact Holstein males mean 180 days old ; Group 2, extensively-reared

Ž .

beef-breed females mean 230 days ; Group 3, extensively-reared castrated beef-breed males

Žmean 253 days . Calves in each group were assigned to one of three handling aid treatments. Žns5 per treatment subgroup; total ns45 : electric prod Prod , oar with rattles Oar , manual. Ž . Ž .

Ž .

urging Manual . Treatments were applied only as needed to encourage forward movement of calves through the length of a solid-sided semicircular chute system. Number of treatment applications, length of time required to move through the entire chute system, and behavior during movement through the chute were recorded. An approach test was conducted 1 day before and 1 day and 1 week after chute tests to evaluate changes in behavior due to handling aid application.

Ž .

During chute tests, Group 1 Prod calves required the fewest treatment applications 4.9 vs. 23.5

ŽOar or 13.5 Manual , ran most often 1.40 times vs. 0.20 times Manual or 0.33 times Oar ,. Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Ž Ž . Ž .

and made contact with chute sides most often 1.8 times vs. 0.2 times Manual or 0.7 times Oar ,

Ž .

respectively all P-0.05 . Similar trends were observed for calves in Groups 2 and 3. There were no significant differences between behaviors observed during the approach tests conducted before and after handling aid treatments had been imposed. Regardless of treatment, intensively-reared Group 1 calves appeared markedly less fearful of handlers during approach tests compared to extensively-reared calves in Groups 2 and 3, which demonstrated overt attempts to escape from the test facilities. One week after chute tests, 13 of 15 Prod calves from all three groups walked, rushed, or backed )1 m away from the handler when the prod was buzzed but not applied, suggesting that the buzzing sound alone may have sufficed to encourage movement by calves that

)Corresponding author. Tel.:q1-301-405-0048.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] C.C. Croney .

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Ž .

had previously experienced both the sensation and sound associated with electric prodding.

q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Behavior; Cattle; Electric prod; Handling aids

1. Introduction

Handling of cattle is required for routine husbandry procedures such as movement, restraint and transportation. As a practical matter, the use of a handling aid is sometimes required, but it is essential to first identify a suitable aid and then apply it correctly to

Ž .

effectively encourage movement Grandin, 1993 . When handling methods are inappro-priate, cattle may exhibit undesirable behavior, or become distressed and even injured. Moreover, a handler may become frustrated by uncooperative cattle and resort to unnecessarily forceful methods of encouraging movement, which may result in injury to handler, animal, or both. Further, rough handling experiences may result in overly excitable, unapproachable cattle, consequently compromising labor efficiency. In fact,

Ž .

Rickenbacker 1959 observed that excessive use of handling aids caused cattle to become so confused and excited that the aids actually hindered rather than facilitated movement. Understanding reactions of animals to improper handling can help a handler recognize and respond appropriately to situations in need of improvement. Reducing the distress caused by poor handling presumably, would in turn, decrease the likelihood of chronically activating the sympatho-adrenomedullary system that may result in reduced

Ž

fertility, decreased milk yield and increased aggression Mateo et al., 1990; Willner, .

1993 .

Few in-depth studies exist relating the behavioral responses of farm animals in general, and cattle in particular, to the use of specific handling aids. Electrical prods, for instance, are frequently used to expedite handling and movement and can be quite

Ž .

effective when applied correctly and in appropriate situations Grandin, 1980 . When Ž

used to load pigs, they can produce rapid, relatively orderly movement Guise and .

Penny, 1989 . Nonetheless, there is evidence that when used inappropriately, electrical prods and other handling aids may have detrimental effects on the behavior and

Ž .

physiological status of some farm animals. Hemsworth et al. 1987 found that pigs that were electrically prodded had higher elevations of free corticosteroids when approached by humans than did those that had not been prodded. Also, pigs that were electrically prodded were hesitant to eat when they could see a person in front of their trough and

Ž .

subsequently exhibited aggressive behavior toward handlers Bresson, 1982 . Further, when pigs that approached humans were electrically prodded, they subsequently became more hesitant to approach people, and were less inclined to interact with handlers ŽHemsworth et al., 1987 . Consequently, some organizations have recommended abol-.

Ž .

ishing the use of electrical prods for animal handling Guise and Penny, 1989 . Although electrical prods are often used to facilitate handling and movement of cattle, relatively little has been reported about the behavioral responses of cattle to

Ž .

electrical prodding. Lefcourt et al. 1985 noted that because cattle have very low

Ž .

Ž . them to respond by lifting their legs, kicking or swaying. Lefcourt et al. 1986 also found that cattle behavior was sometimes dramatically affected when they were shocked. When restrained cows were shocked at electrical intensities ranging from 2.5 to 10.0 mA, they responded so violently that their safety and well-being were jeopardized ŽLefcourt et al., 1986 . In fact, cows that were shocked at currents of 12 mA were.

Ž .

unapproachable Lefcourt et al., 1985 .

Because electrical prods and other handling aids are used to facilitate movement of various breeds of calves, an experiment was designed to determine the behavioral responses of different types of calves to the application of one of three kinds of handling aids. Calves’ initial responses to a stationary and approaching handler were recorded and compared with their responses to the same handler after they had experienced one of three different aids. Further, to contrast the efficacies of the aids, the number of applications and length of time required to effect forward movement of calves through a

Ž .

chute using each of the different aids were recorded.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and treatments

Three groups of calves were used: Group 1 consisted of 15 intact Holstein males

Ž . Ž .

172–187 days old mean 180 days , weighing 145–182 kg mean 158 kg ; Group 2 Ž

consisted of nine Angus and six Simmental intact heifers 205–292 days old mean 236

. Ž .

days , 189–348 kg mean 290 kg ; Group 3 consisted of seven Angus, three Simmental,

Ž .

and five Hereford castrated males 221–297 days old mean 253 days , 246–343 kg Žmean 310 kg . In addition to breed and gender disparities, several differences existed. between groups prior to the study. Group 1 calves had previously been reared indoors and had no prior experience with either restraint or chute. Also, they had been manually handled frequently prior to initiation of the experiment. In contrast, Groups 2 and 3 calves were reared outdoors, and had experienced restraint in a chute system prior to the experiment, but had been only infrequently handled. With the exception of manual handling, none of the calves had previously experienced the handling aids used in the study. Because of the confounding associated with these factors, the effects of group were accounted for in the statistical analyses to be described later.

Ž

For each group, calves were randomly allotted to five trios stratified by body .

weight . Each trio was then randomly assigned to one of the three handling-aid Ž

treatments: Prod — electric prod Model HS2000, Hotshot Products, Savage, MN; 3.3

w x Ž x.

kV, 700 mA with 500 Vload, alternately on 0.08 ms and off 100.00 ms ; Oar — oar

Ž .

with rattles Koehn Marketing, Watertown, SD; 122 cm long ; or Manual — manual

Ž .

urging bare-hand slap on calf rump .

2.2. Procedures

2.2.1. Adjustment

Each group of 15 experimental and five companion calves was moved to an outdoor pen to adjust for 2 weeks. The adjustment period was granted to accustom the calves to group housing in new facilities, as it was necessary to move them from their previous quarters to new pens near the testing site. The 2-week period was therefore deemed sufficient for the calves to recover from any distress caused by the move and the novel surroundings. All calves were fed the same quantity of the same diet throughout the adjustment and experimental periods.

2.2.2. Initial approach test

To assess individual calves’ respective initial reactions to a human in close proximity,

Ž .

an approach test was conducted on the day before the chute tests Day 0 . A handler directed each trio of calves plus a randomly selected companion calf from the outdoor group pen into a small indoor holding pen. After a 15-min rest period, one experimental calf was separated at random and driven approximately 3 m to the test area where it remained in auditory but not visual contact with its conspecifics during the test. This procedure was repeated until all calves in the trio had been approach-tested. All trios were similarly tested.

Ž .

The test area was constructed of pipe gates sheathed with plywood 1.22 m high

Ž .

arranged as an octagon minimum radius 3.68 m . The ground was covered to 8 cm with wood chips. As a calf entered the test area, a handler stood motionless in the center of the area, holding the calf’s assigned handling aid at a 458angle against his body so that the tip of the aid rested against the handler’s right shoulder. If the calf approached the

Ž

handler within 1 min, an observer recorded the hesitation time defined as its latency to .

approach handler , as well as the distance it moved towards the handler. If it did not approach, then for 4 min, the handler continuously walked towards the calf. The distance Žif any the handler walked before the calf moved away was also recorded. This distance. was defined as the calf’s flight zone. The calf’s behavior in response to being approached was also recorded.

To verify distances and further evaluate behavior, the test area was video-recorded

Ž .

using a video camera Model WV-BP 100rWV-BP104, Panasonic, Secaucus, NJ ,

Ž .

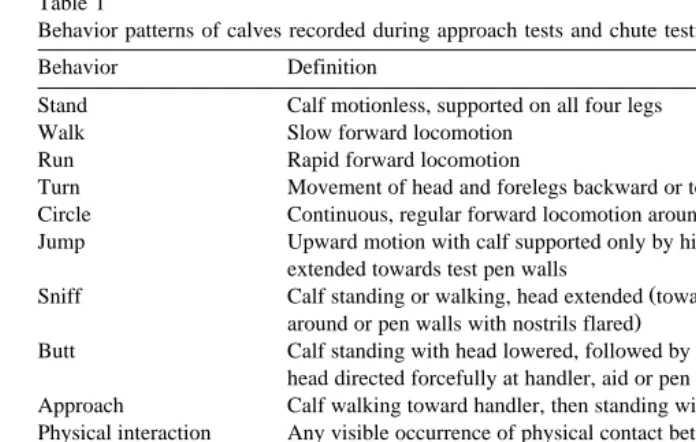

video recorder Model VCR4000, Emerson Radio, Princeton, IN , and wide-angle lens ŽComputar APC 3.6 mm TV lens, Chugai International, Commack, NY . All behaviors. that were observed were recorded. These included: stand, walk, butt, run, circle, sniff groundrhandlerrpen, approach, and escape attempt. A detailed ethogram is presented in Table 1. At the end of the approach test, the calf was returned to the indoor holding pen.

2.2.3. Chute tests

Tests of calves’ behavioral reactions to being driven through a solid-sided, semi-cir-Ž

cular chute system 18.5 m long, Powder River Livestock Handling Equipment, Provo,

. Ž .

Table 1

Behavior patterns of calves recorded during approach tests and chute testing

Behavior Definition

Stand Calf motionless, supported on all four legs

Walk Slow forward locomotion

Run Rapid forward locomotion

Turn Movement of head and forelegs backward or to the side

Circle Continuous, regular forward locomotion around perimeter of test area Jump Upward motion with calf supported only by hind legs, forelegs raised and

extended towards test pen walls

Ž

Sniff Calf standing or walking, head extended toward handler, movement aid,

.

around or pen walls with nostrils flared

Butt Calf standing with head lowered, followed by forward movement with head directed forcefully at handler, aid or pen walls

Approach Calf walking toward handler, then standing within 0.5 m of handler Physical interaction Any visible occurrence of physical contact between calf and handler Allow approach Calf standing or walking while permitting handler to move within 0.5 m

of its body

Escape attempt Calf running toward test pen walls, followed by jumping

Stumble Forward locomotion interrupted by visible buckling of calf’s knees or legs Side contact Calf bumping forcefully against walls of chute

Investigate Sniffing or licking handler, handling aid, test pen walls or ground Balk Standing motionless, refusing to move despite handling aid application

The prod was applied for no longer than 1 s per occasion, and was used only as Ž

necessary to effect the calf’s progress through the chute e.g., the aid was only applied if .

the calf stopped moving forward . Oar calves were lightly struck on the right rump with that aid one time before the sliding door was opened, and again, as needed to effect forward movement. As described for the prod, the oar was applied only when the calves stopped moving. Manual calves were gently slapped once on the right rump with a bare hand prior to entry into the chute system. To the extent that it was possible to do so, the

Ž .

handler used the same amount of force each time a handling aid or slap was administered. The number of prod applications, oar strikes, or hand slaps required to move the calf through the chute was recorded. Additionally, the number of stop, turn, run, walk, investigate, contact side, refuse, and stumble behaviors were recorded. The total handling time and the actual handling time were also recorded. Total handling time

Ž

was defined as time required to separate the calf from its trio including the 20-s period .

of interaction with the aid to the time the calf exited the scale at the end of the chute system. Actual time was defined as the time taken from the moment the calf entered the sliding door at the chute entry to the time the calf stepped onto the chute’s scale. After the first trio had been tested, the next trio of calves within the assigned handling aid group was tested, and so on, until all had been tested.

2.2.4. Subsequent approach tests

To determine the effects of the respective handling aids on the calves subsequent

Ž .

Table 2

Frequenciesaof behaviors observed during approach tests for Groups 1, 2 and 3 calves

Ž . Ž .

Means in the same row with different superscripts b, c, d differ; ns5rtreatment P-0.05 .

Ž . Ž .

Means in the same row with different superscripts e, f, g differ; ns5rtreatment P-0.10 .

Item Treatment Pooled SEM Friedman’s P

Manual Oar Prod

GROUP 1

Before handler approach

Stand 2.60 2.47 2.27 0.31 0.98

e f g

Ž .

Sniff pen 0.87 1.00 0.40 0.22 0.10

Ž .

Sniff ground 0.27 0.60 0.27 0.16 0.16

Ž .

Sniff handler 0.47 0.80 0.60 0.22 0.82

Walk 1.87 2.20 1.47 0.37 0.86

Run 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

Circle 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

Approach 0.53 0.80 0.87 0.29 0.72

Escape attempt 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

After handler approach

bc b c

Stand 7.33 5.47 9.07 0.76 0.01

Ž .

Sniff pen 3.13 2.93 3.67 0.49 0.76

e f g

Ž .

Sniff ground 1.80 1.80 3.40 0.50 0.07

b c d

Ž .

Sniff handler 0.73 2.87 1.20 0.46 0.01

bc b c

Walk 7.27 6.20 9.20 0.90 0.08

Run 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

Circle 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

Approach 3.80 3.73 4.40 1.10 0.47

Escape attempt 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

GROUP 2

Before handler approach

Stand 4.32 3.87 3.40 0.46 0.67

Ž .

Sniff pen 2.40 1.93 1.80 0.43 0.94

b c d

Ž .

Sniff ground 0.79 1.33 0.40 0.27 0.03

Ž .

Sniff handler 0.22 0.33 0.27 0.15 0.76

Walk 2.52 2 .93 2.39 0.48 0.80

b c bc

Run 0.40 0.00 0.20 0.15 0.01

b c d

Circle 1.45 0.50 0.20 0.37 0.00

Approach 0.42 0.27 0.33 0.18 0.37

Escape attempt 0.01 0.00 0.07 0.04 0.16

After handler approach

Stand 15.03 15.33 16.13 1.59 0.69

Ž .

Sniff pen 10.21 9.27 7.87 1.28 0.40

Ž .

Sniff ground 2.55 1.93 2.27 0.64 0.87

Ž .

Sniff handler 1.11 1.40 2.40 0.49 0.39

Walk 10.35 10.87 12.73 1.73 0.68

Run 1.88 1.33 0.53 0.48 0.14

Circle 5.85 4.27 4.33 1.20 0.24

Approach 6.21 6.33 5.80 1.24 0.72

b c c

Ž .

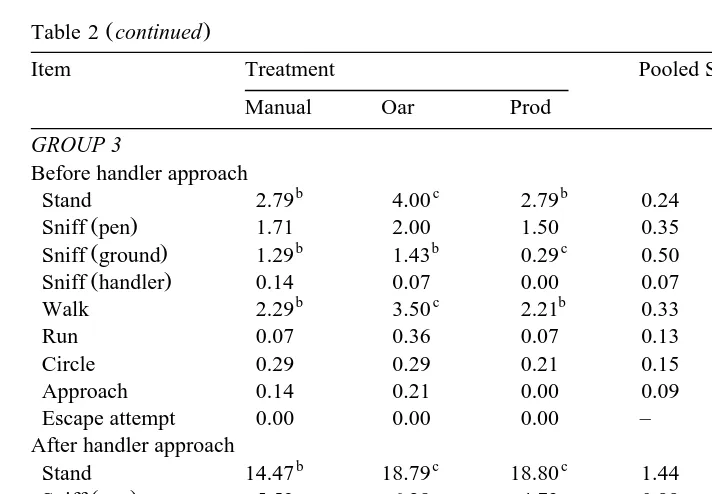

Table 2 continued

Item Treatment Pooled SEM Friedman’s P

Manual Oar Prod

GROUP 3

Before handler approach

b c b

Stand 2.79 4.00 2.79 0.24 0.01

Ž .

Sniff pen 1.71 2.00 1.50 0.35 0.62

b b c

Ž .

Sniff ground 1.29 1.43 0.29 0.50 0.01

Ž .

Sniff handler 0.14 0.07 0.00 0.07 0.61

b c b

Walk 2.29 3.50 2.21 0.33 0.02

Run 0.07 0.36 0.07 0.13 0.52

Circle 0.29 0.29 0.21 0.15 0.96

Approach 0.14 0.21 0.00 0.09 0.37

Escape attempt 0.00 0.00 0.00 – –

After handler approach

b c c

Stand 14.47 18.79 18.80 1.44 0.13

Ž .

Sniff pen 5.53 6.29 4.73 0.99 0.48

Ž .

Sniff ground 2.13 3.93 1.93 0.70 0.18

b c c

Ž .

Sniff handler 4.87 2.43 2.33 0.65 0.04

b c c

Walk 13.87 17.07 19.67 1.53 0.03

Run 1.27 0.71 0.60 0.53 0.81

Circle 1.00 1.00 0.27 0.34 0.43

Approach 13.67 12.13 11.93 0.87 0.63

Escape attempt 0.07 0.36 0.00 0.18 0.17

a

Frequencies denote the number of times a behavior was observed during a test period.

2.2.5. Reactions to sound of handling aid alone

Prior to each calf’s release at the end of the Day 7 test, the handler returned to the center of the test area and resumed holding the handling aids against his body as previously described. For 30 s, the handler buzzed the prod or rattled the oar in the presence of each Prod or Oar calf, respectively, while observers recorded the calves’ responses.

To avoid differences in responses due to different handlers, the same handler and observers were used for the entire test procedure for each group of calves.

2.3. Statistics

Ž .

Continuous data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance Minitab, 1996 . Ž

Because there were numerous pre-existing group differences e.g., gender, age, housing .

and breed between the three groups of calves, preliminary data analyses of the approach test data were conducted. These analyses indicated significant interactions between main

Ž .

effects Group X Treatment which precluded combining all data. Therefore, each group’s approach test and chute test data set were analyzed separately. Data sets, which were not normally distributed, were transformed by deriving their square roots prior to

Ž . Ž

analysis of variance Steel and Torrie, 1980 . Pearson’s correlation procedure Steel and .

spent handling the calf in the chute area, actual time required to move the calf through the chute, and number of handling-aid applications required to move the calf through the chute.

3. Results

3.1. Approach tests

Frequencies of behavior patterns observed during the approach tests conducted after treatments were imposed are presented in Table 2. No significant differences were observed between approach test behaviors observed before and after administration of

Ž .

handling aids for any of the groups all P)0.10 . There were also no significant differences between behaviors observed during approach tests conducted 1 day and 1

Ž .

week after chute testing all P)0.10 . Therefore, the means of the three approach test

Ž .

results are presented Table 2 . In response to a stationary handler, Group 1 Manual and

Ž .

Oar calves sniffed the pen more often than did Prod calves P-0.10 . In response to an

Ž . Ž .

approaching handler, Prod calves stood P-0.05 and walked P-0.05 more often than did Manual or Oar calves. Oar calves sniffed at the approaching handler more

Ž .

frequently than Manual or Prod calves P-0.05 . In response to a stationary handler,

Ž . Ž .

Group 2 Manual calves ran P-0.05 and circled the test area P-0.01 more often than did Prod or Oar calves. Oar calves sniffed the ground more frequently than did

Ž .

Manual or Prod calves P-0.05 . In response to handler approach, Manual calves in this group attempted to escape from the test arena more often than Oar or Prod calves ŽP-0.05 . In Group 3, Oar calves stood P. Ž -0.01 , walked P. Ž -0.05 and sniffed the.

Ž .

ground P-0.05 before the handler approached, more often than did Prod or Manual

Ž .

calves. In response to an approaching handler, Manual calves walked P-0.05 less often than Oar or Prod calves but Manual calves also sniffed at the handler more often

Ž .

than Oar or Prod calves P-0.03 .

3.2. Chute tests

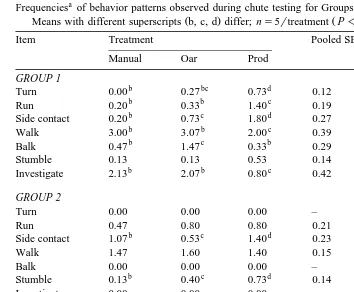

Frequencies of behavior patterns during chute tests have been categorized by treatments within the three animal groups in Table 3. In Group 1, Prod calves turned, ran, and made contact with the sides of the chute more often than did Manual or Oar

Ž .

calves all P-0.01 . Prod calves also balked and attempted to investigate the chute

Ž .

area less often than Manual or Oar Calves both P-0.05 . In Group 2, Prod calves stumbled and made contact with the sides of the chute more often than Oar or Manual

Ž .

calves both P-0.05 . In Group 3, Prod calves ran, made contact with chute sides, and

Ž .

stumbled more often than Manual or Oar calves all P-0.01 .

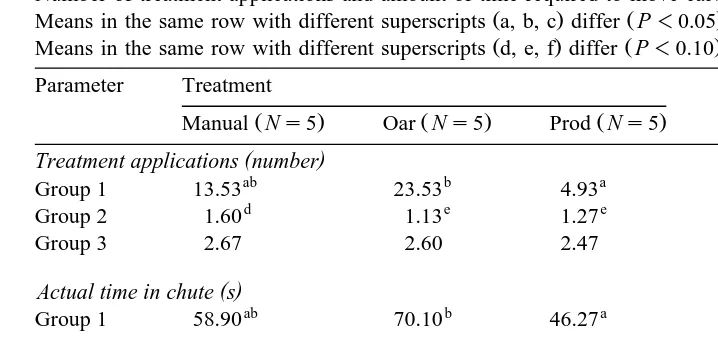

The duration of chute-test trials is summarized in Table 4. In Group 1, the actual time Žtime taken to travel the length of the chute was less for Prod calves 46.27 s than. Ž .

Ž . Ž .

Table 3

Frequenciesaof behavior patterns observed during chute testing for Groups 1, 2 and 3 calves

Ž . Ž .

Means with different superscripts b, c, d differ; ns5rtreatment P-0.05 .

Item Treatment Pooled SEM Friedman’s P

Manual Oar Prod

GROUP 1

b bc d

Turn 0.00 0.27 0.73 0.12 0.01

b b c

Run 0.20 0.33 1.40 0.19 0.01

b c d

Side contact 0.20 0.73 1.80 0.27 0.01

b b c

Walk 3.00 3.07 2.00 0.39 0.04

b c b

Balk 0.47 1.47 0.33 0.29 0.01

Stumble 0.13 0.13 0.53 0.14 0.32

b b c

Investigate 2.13 2.07 0.80 0.42 0.02

GROUP 2

Turn 0.00 0.00 0.00 – –

Run 0.47 0.80 0.80 0.21 0.28

b c d

Side contact 1.07 0.53 1.40 0.23 0.02

Walk 1.47 1.60 1.40 0.15 0.50

Balk 0.00 0.00 0.00 – –

b c d

Stumble 0.13 0.40 0.73 0.14 0.03

Investigate 0.00 0.00 0.00 – –

GROUP 3

Turn 0.00 0.00 0.00 – –

b b c

Run 0.33 0.33 1.47 0.16 0.01

b c d

Side contact 0.47 0.33 3.33 0.25 0.01

b b d

Walk 1.33 1.47 0.47 0.14 0.01

Balk 0.07 0.00 0.07 0.05 0.61

b b c

Stumble 0.27 0.13 0.73 0.15 0.01

Investigate 0.00 0.00 0.00 – –

a

Frequencies denote the number of times a behavior was observed during a test.

Ž

3 for actual time in the chute. Differences in total time time required to move calves . from the crowd pen into the chute and to travel through and exit the chute area were

Ž .

observed for Group 1. Prod calves required least total time 84.10 s vs. 102.3 s ŽManual and 103.8 s Oar . No differences were observed for Groups 2 or 3 calves for. Ž . this category. The number of treatment the applications required to effect forward progress through the chute are also summarized in Table 4. Group 1 Prod calves

Ž

required the fewest treatment applications Manual: 13.53; Oar: 23.53; Prod: 4.93;

. Ž

P-0.01 . Group 2 Prod and Oar calves required fewer treatment applications 1.27 and

. Ž .

1.13, respectively than Manual calves 1.60 . No differences were observed in this category for Group 3 calves.

Ž .

There was positive correlation rs0.95; P-0.05 between the number of handling-aid applications and actual time spent in the chute for all groups. Similarly, total

Ž

handling time and actual time spent in the chute were positively correlated rs0.94; .

Table 4

Number of treatment applications and amount of time required to move calves through the chute system

Ž . Ž .

Means in the same row with different superscripts a, b, c differ P-0.05 .

Ž . Ž .

Means in the same row with different superscripts d, e, f differ P-0.10 .

Parameter Treatment Pooled SEM P

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Manual Ns5 Oar Ns5 Prod Ns5

( )

Treatment applications number

ab b a

Group 1 13.53 23.53 4.93 4.27 0.01

d e e

Group 2 1.60 1.13 1.27 0.15 0.09

Group 3 2.67 2.60 2.47 0.35 )0.10

( ) Actual time in chute s

ab b a

Group 1 58.90 70.10 46.27 15.10 0.05

Group 2 13.93 14.93 15.80 0.77 )0.10

Group 3 13.47 13.53 14.40 0.71 )0.10

( ) Total time in chute area s

a a b

Group 1 102.30 103.80 84.10 20.18 0.05

Group 2 37.07 40.50 39.27 0.71 )0.10

Group 3 36.73 38.60 37.90 0.98 )0.10

3.3. Reactions to sound of handling aid alone

Ž .

On Day 7 1 week after handling-aid application in chute tests , most Prod and Oar calves appeared to respond behaviorally to the respective sounds of these handling aids

Ž .

alone. 13 of 15 Prod calves moved away )1 m and eight of them, )2 m from the handler when the electric prod was buzzed in their vicinity. Two responded to the sound of the prod by bucking and running around the test area. Similar responses were observed in 11 of 15 Oar calves when the oar was shaken but not applied on Day 7. One Oar calf attempted to mount the handler, and two others butted the handler in response to the shaking sound of the Oar.

4. Discussion

The finding of no significant differences for any group between approach test behaviors observed before and after handling aid administration suggests that brief exposure to a particular handling aid may be insufficient to alter calves’ behavioral reactions to a handler during subsequent approach tests. These results imply that the use of the aids in the chute test environment did not subsequently cause the calves to behave differently towards a handler that merely held the same aids in a different setting.

which were of dairy breeding and previously had been extensively handled in an indoor setting, appeared relatively undisturbed during approach tests, regardless of the handling

Ž

aid experienced. In fact, calves that were electrically prodded presumably, the most .

aversive of the handling treatments were no less hesitant to approach or interact with a stationary or approaching handler after treatments were imposed, and no overt fear

Ž .

responses e.g., escape attempts were observed during any of the approach tests. In Ž

contrast, calves in Groups 2 and 3 of beef breeding and previously handled less

. Ž

frequently than Group 1 calves frequently displayed fear responses e.g., escape . attempts, repeated circling of the pen’s perimeter, and running away from the handler during approach tests. These observations suggest that the previous handling experience of the calves may have influenced their behavior patterns in agreement with the results

Ž . Ž . Ž .

of Boissy and Bouissou 1988 , Trunkfield and Broom 1990 and Gonyou 1993 . However, because the current experiment was not designed to compare the effects of factors, such as breed and previous handling experience, on approach test behavior, but

Ž

rather, was aimed only at clarifying the effects of the aids as a function of breed, .

experience, etc. these observations are not based on statistical inference, and perhaps, should be investigated in future studies.

Despite their apparent inability to alter the calves’ behavior from one approach test to the next, some effects of handling aids were observed both within and across groups during the approach test conducted 1 day after the treatments were administered. For

Ž example, regardless of group, Oar calves engaged in more investigatory behavior e.g.,

.

sniff handling aid or handler than did Prod or Manual calves. This might have been due to the oar’s rattling sound, which sometimes unintentionally occurred, even when the oar was not applied. Perhaps, the novel rattling sound caused the Oar calves to become curious about the source of the noise, so they investigated it, as suggested by Fraser Ž1974 . In contrast, Prod calves tended to investigate e.g., sniff handling aid or handler. Ž . less often than did Manual or Oar calves. Perhaps, this tendency to avoid the handler and the handling aid occurred because these calves were more fearful of the handler and Ž .or the aid than calves handled differently, and they subsequently tried to avoid further

Ž .

contact. This agrees with Fraser’s 1974 claim that animals rarely explore when they are fearful.

In some instances, Manual calves in Groups 2 and 3 investigated more frequently Ž

than Oar or Prod calves, but then, also displayed more fear responses e.g., running, .

circling the arena, and attempting to escape . This finding was unexpected. Evidently, the Manual calves in these groups were disturbed by some aspect of the approach test procedure, and may have investigated their surroundings primarily to find some means

Ž . of escaping. Similar results have been reported by Stephens and Toner 1975 who found elevated heart rates in calves that nonetheless appeared outwardly calm in response to an approaching handler.

Although the behavior patterns of the calves remained relatively unchanged when the handler simply held the aids, it was observed that when the same handler buzzed the

Ž

prod or rattled the oar at the end of the final approach test but did not move toward the .

Ž .

of the electric prod or the rattling sound of the oar with the presumably unpleasant sensations that accompanied application of those aids. Learning which occurs under conditions of fear or distress tends to be well retained and may allow an animal to avoid

Ž .

extremely noxious stimuli after even one experience Beilharz, 1985 . The observation that the calves responded to the sound of the aids alone after a week supports Grandin’s Ž1980 theory that once a calf has heard the sound that accompanies an application of an. aversive sensation, that sound alone may suffice to encourage movement away from a handler.

The results of the chute test demonstrated that electrically prodded calves required fewest treatment applications and the least time to move into and through the length of the chute. However, although the Prod calves moved most rapidly, they also stumbled

Ž .

and contacted the chute sides most often. Rickenbacker 1959 similarly reported that when handling aids were applied in a manner that elicited unnecessarily rapid animal movement, increased incidences in the number of contacts with stationary parts of the

Ž .

facility e.g., the number of potential bruise-causing incidents resulted. The findings in Ž .

this study also concur with Gonyou’s 1993 belief that animals should not be hurried during movement because of the likelihood of missteps and other accidents occurring. Overall, the results of this experiment suggest that brief exposure to a specific handling aid may not significantly alter calves’ subsequent behavioral responses to stationary or approaching handlers that are not attempting to apply aids. The calves’ responses during such circumstances are perhaps less influenced by the type of handling aid experienced in one instance, than by other aspects of handling, such as isolation, and previous experience with handling procedures and facilities. However, upon hearing the sound of a handling aid that has been experienced, calves may respond by moving away. Thus, there may be instances when the sound of a handling aid alone would suffice to encourage calf movement. This possibility should be investigated further.

Despite differences in breed, gender and previous experience, calves in all groups that

Ž .

were electrically prodded in a confined area a chute system tended to rush away from handlers, stumble and make contact with the sides of the chute and other parts of the facilities more frequently than calves that were handled differently. Repeated electrical prodding of calves in a confined area should be avoided altogether, and particularly, immediately prior to slaughter, because consequent injuries to animals can have negative

Ž .

impacts on both their well-being and economic returns Grandin, 1993 . Thus, it is important that handlers select appropriate handling aids and apply them correctly. Correct application procedure includes applying the aid only to calves that have stopped moving and are able to move away from the handler, and terminating that application once the calf has begun to move in the desired direction.

Acknowledgements

References

Ž .

Beilharz, R.G., 1985. Learned behaviour. In: Fraser, A.F. Ed. , World Animal Science, Ethology of Farm Animals. Elsevier, New York, pp. 93–102.

Boissy, A., Bouissou, M.F., 1988. Effects of early handling on heifers’ subsequent reactivity to humans and to unfamiliar situations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 20, 259–273.

Ž .

Bresson, S., 1982. Influence of long term psychical stress noise, fighting and electrical stimulation on the physiology and productivity of growing-finishing pigs. In: Livestock Environment II: Proceedings of the Second International Livestock Environment Symposium. American Society of Agricultural Engineers, St. Joseph, pp. 449–456.

Fraser, A.F., 1974. Farm Animal Behaviour. Balliere Tindall, New York.

Ž .

Gonyou, H., 1993. Behavioural principles of animal handling and transport. In: Grandin, T. Ed. , Livestock Handling and Transport. CAB International, Wallingford, Oxon, UK, pp. 11–20.

Grandin, T., 1980. Livestock behavior as related to handling facilities design. Int. J. Stud. Anim. Prod. 1, 33–52.

Ž .

Grandin, T., 1993. Behavioural principles of cattle handling under extensive conditions. In: Grandin, T. Ed. , Livestock Handling and Transport. CAB International, Wallingford, Oxon, UK, pp. 43–57.

Guise, H.J., Penny, R.H.C., 1989. Factors influencing the welfare and carcass and meat quality of pigs. Anim. Prod. 49, 511–515.

Hemsworth, P.H., Barnett, J.L., Hansen, C., 1987. The influence of inconsistent handling by humans on the behaviour, growth and corticosteroids of young pigs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 17, 245–252.

Lefcourt, A.M., Akers, R.M., Miller, R.H., Weinland, B., 1985. Effects of intermittent electrical shock on responses related to milk ejection. J. Dairy Sci. 68, 391–401.

Lefcourt, A.M., Stanislaw, K., Akers, R.M., 1986. Correlation of indices of stress with intensity of electrical shock for cows. J. Dairy Sci. 69, 833–842.

Mateo, J.M., Estep, D.Q., McCann, J.S., 1990. Effects of differential handling on the behaviour of domestic

Ž .

ewes OÕis aries . Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 32, 45–54.

Minitab, 1996. Minitab Reference Manual, Release 11 for Windows. Minitab, State College, PA.

Rickenbacker, J.E., 1959. Handling conditions and practices causing bruises in cattle. Marketing Res. Rep. 346, Farmer Cooperative Service, US Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC.

Steel, R.G.D., Torrie, J.H., 1980. In: Principles and Procedures of Statistics, A Biometrical Approach. Mc-Graw Hill, New York, pp. 546–547.

Stephens, D.B., Toner, J.N., 1975. Husbandry influences on some physiological parameters of emotional responses in calves. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 1, 233–243.

Trunkfield, H.R, Broom, D.M., 1990. The welfare of calves during handling and transport. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 28, 135–152.

Ž .