SPECIAL ISSUE

SOCIAL PROCESSES OF ENVIRONMENTAL VALUATION

The Bouchereau woodland and the transmission of

socio-ecological economic value

Jean-Franc¸ois Noe¨l, Martin O’Connor, Jessy Tsang King Sang *

C3ED,Uni6ersite´ de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Y6elines,47 boule6ard Vauban,78047 Guyancourt Cedex, France

Abstract

This paper reports on an empirical study that investigated the value, or significance, attributed to a rural woodland, and the social mechanisms by which this value may be transmitted (or lost) through time. A survey-interview enquiry was conducted which combined a data questionnaire with in-depth interview procedures, centred around: (i) the transaction price for the privately owned plots of trees and (ii) the disposition of wood-lot owners towards eventual sale of their plots, and the circumstances under which they would envisage such transactions. The forest value needs to be understood in patrimonial perspective, as a collective investment. The woodland as a whole, and the plots individually, are carriers of meaning — elements of family and communal heritage — proudly inherited from the previous generations and destined to be passed on to future generations. The case study illustrates a more general proposition, that evaluation of alternative uses of environmental resources, and their benefits and costs, is inseparable from the question of the distinct communities of interest to be, or not to be, sustained. © 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Common property; Ecological economics; Environmental valuation; Forest values; Methodology; Patrimonial tradition; Social process; Sustainability; Willingness-to-accept

www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon

1. Introduction

The economics of the industrial age has fo-cussed mostly on mechanisms of production and exchange of commodities (produced capital and consumption goods). This commodity production activity is represented as drawing upon an exter-nal (environmental) domain that furnished raw

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 5th Biennial Meeting of the International Society for Ecological Economics, Beyond Growth: Policies and Institutions for Sus-tainability, Santiago, Chile, 15 – 19 November 1998.

* Corresponding author. Tel.:+33-1-39255375; fax:+ 33-1-39255300.

E-mail address: [email protected] (J. Tsang King Sang).

materials and waste disposal services. If, subse-quently, it is admitted that there are environmen-tal disruptions associated with this economic commodity production, the question from an ‘op-timising’ point of view becomes to know whether the economic benefits outweigh the environmental costs.

On this basis, various methods have been devel-oped for trying to put money values on environ-mental assets through establishing trade-offs between money-valued goods and environmental amenities or damages. And in this way, through the enlargement of cost-benefit analysis to the environmental domain, it has been hoped to provide a framework for a ‘rational’ governance of economic output growth in relation to quality of the environment. But, comparison of alterna-tive uses of environmental assets, and the

assess-ment of risks and impairment of habitat

conditions due to pollutants and ecosystem dis-ruption, pose difficulties of high uncertainties, the irreversibility of many effects, and (thus) long time-scales. The notion of ‘substituting’ or ‘com-pensating’ one specific value loss by another gain becomes difficult to sustain when the losses and gains are of very different sorts and the winners and losers (so to speak) far dispersed across space and time.

If we want to provide decision support while we enlarge our scope of concern to the ecosystems of the planet and the long term, it is necessary to develop dis-aggregated perspectives on values — paying attention to the social processes by which value — or significance — is attributed, dis-tributed, and redistributed across space and through time. One theme within ecological eco-nomics is the representation of ‘sustainable

devel-opment’ as a symbiosis between economic

production and ecological (re)production. This puts an emphasis on managing and investing in the reproduction, transformation and renewal of the bio-physical ‘life-support’ systems that under-pin commodity production systems. However, out of the range of all possible economic and ecologi-cal trajectories, there are choices having to be made about which environmental features and functions, which ecosystems and habitats, and which spectra of economic opportunities, might

be sustained — and for whom? Valuation is about understanding, explaining and justifying the choices made, or the alternatives that might be preferred.

Decision support for public policy in this con-text must seek to articulate reasons and justifica-tions (touching domains of ethics, norms, cultural and social organisation principles), for alternative courses of action whose intent is to sustain this or that particular form of life, mode of economic activity, ecosystem, landscape quality and so on. The husbandry of living resources, the minding and tending of ecosystems, are forms of investing in a future that is meaning-filled (culturally formed) as well as viable in ecological economic terms; in this multiple sense we may speak of the transmission of value. This paper applies methods and perspectives for increasing our understanding of the social mechanisms by which value, in these

socio-ecological-economic dimensions, is

at-tributed and transmitted (or lost) through time by human communities. We will thus speak of valua-tion as a collective process, involving arguments and actions for — and against — the transmis-sion of specific value claims.

eventual sale of their plots of trees. Section 5 discusses these results concerning monetary and non-monetary dimensions of lot and wood-land value, showing how the value attributed to the forest needs to be understood in patrimonial perspective as a collective investment of meaning as well as of time. Sections 6 and 7 conclude with discussions of methodological lessons for environ-mental valuation in the context of socio-ecological economic sustainability concerns.

2. Valuation as a selection process amongst different prospects of ecological-economic symbiosis

Our terrestrial habitats are not just raw materi-als sources and waste sinks, but veritable life-sup-port systems that are invested with social and community significance, or meanings. So valua-tion practices cannot be separated from the idea of actions whose effect is to sustain this or that form of life, way of life — in the cultural as well

as ecological-economic sense (O’Connor,

1997a,b).

The view of sustainable development as a pro-cess based on cycles of renewal and regeneration, a symbiosis of ecological and economic reproduc-tion, was already present in the concept of eco-de-velopment expounded in the early 1970s by some international agencies, at first with reference mainly to rural development projects in the Third World. At that time it joined a large array of concepts and terminologies proposing an ‘alterna-tive’ development, whose common feature was rejection of the dominant views of development couched in terms of rapid GNP-growth, through-put of resources, and technological modernisa-tion. More specifically, as Ignacy Sachs (1980, p. 37) wrote:

Ecodevelopment is a development of peoples through themselves utilising to the best the natural resources, adapting to an environment which they transform without destroying it. [....] Development in its entirety has to be impreg-nated, motivated, underpinned by the research of a dynamic equilibrium between the life

pro-cess and the collective activities of human groups planted in their particular place and time.

Emphasis here is on ‘the cultural contributions of the peoples concerned’ in the effort to ‘trans-form the various elements of their environment into useful resources’ (Sachs, 1984, pp. 28 – 30). In effect, systems concepts from ecology, such as cycles and functional harmonisation, are trans-posed to the social and organisational domain. In

biophysical terms eco-development aims at

achieving a lasting symbiosis between humanity and the earth; at the social level the search is for a harmonisation of relationships based on co-op-eration at local and international levels to achieve economic equity.

In order to allow resource management deci-sions to be framed incisively we must add a further dimension, that of conflict resolution or choices over sustaining what and for whom? The VALSE project (see O’Connor, 2000, this issue) was about procedures and institutions for social valuations of natural capital in environmental conservation and sustainability policy. The prob-lem that has to be addressed is that a simple invocation of ‘symbiosis’ or ‘sustainability’ as a reference concept does not serve as a decision criterion. It does not, for example, guarantee the conservation of specified productive or reproduc-tive potentialities of any particular society or ecosystem! Nor does it assure the sustaining of all the particular interests, communities, or ecologies thus given hope. So, by introducing the proble´ma-tique of ‘valuation’, we focus on the requirement that human actions, and policy choices more par-ticularly, shall effect decisions about the ‘distribu-tion of sustainability’: which interests and forms of life will be sustained, and which ones left behind, relinquished, destroyed or left to die (O’Connor and Martinez-Alier, 1997; cf. also Sa-muels, 1992a,b on the ‘distribution of sacrifice’).

How might the various candidates for sustain-ability — for example, various terrestrial and

aquatic ecosystems in ‘natural’ or

We are forced to acknowledge incommensurabili-ties (Martinez-Alier et al., 1999). In a typical watershed management situation the maintenance of (say) bird populations and riverbank rural economies through flood management assuring year-round flows, would serve different communi-ties of interest from (say) damming and piping the water for urban supply.

From a decisionmaking and policy assessment point of view there are both advantages and dis-advantages of sacrificing the ideal of full commen-surability of valuations. The VALSE project has emphasised deliberation and decisionmaking pro-cedures that typically will not yield a unique ranking of options, but that make (more) explicit the reasons for and against the different sorts of social choices and ecological and economic trade-offs that might be involved. While this ‘discursive’ approach may seem to imply greater complexity in the way of framing decision problems, an ad-vantage from a scientific (and, for some, from an ethical and aesthetic) point of view is the richer appreciation of the significance to different com-munities of interest of the choices to be made.

The French VALSE case study concerned small forest pockets in agricultural France, in the Gaˆti-nais region some 100 kilometres south of Paris. There are many small such forest islands (ıˆlots boise´s), which have been the object of several recent studies carried out by several different re-search teams looking at various ecological, eco-nomic and social dimensions. From 1992 to 1996, these wooded ‘oases’ were the object of a multi-disciplinary study carried out by a research team from the Muse´um National d’Histoire Naturelle on ‘The future of woodland areas in large agricul-tural plains: the example of north-west Gaˆtinais’ (Blandin, 1996; Blandin and Arnould, 1996; Girard and Baize, 1996). The wooded ‘islands’ were studied essentially in view of their marked isolation compared to two ‘source-continents’ rep-resented by the forest massifs of Fontainebleau and Orle´ans (Linglard, 1992, 2000).

The largest of the woods studied is the Bois de Bouchereau, around 48 hectares, on which a num-ber of natural inventories were made (phyto-eco-logical surveys, transections, pedo(phyto-eco-logical ditches, study of fauna, etc.) as well as legal and economic

studies (see Dubien, 1993; de la Gorce, 1994; Heron, 1997; Noe¨l and Tsang King Sang, 1997). This woodland is situated in open field country called the ‘Gaˆtinais Nord-Occidental’, about 100 km to the south-west of Paris. It is composed of ‘parcels’ held as private property. The woodland has been, through generations, progressively di-vided into (about) 284 wood-lots (in French, par-celles) actually owned by (about) 155 persons.

As Norgaard suggests in his coevolutionary development perspective (Norgaard, 1988, 1994), questions of ecological-economic symbiosis and co-evolution can be considered along several dif-ferent spatial, as well as temporal scales — from a specific ‘local’ communities and territories, through nation states, regions and trade blocs, to the global level. At each scale, one can consider the community or system for itself, and also its exchanges and co-evolution with other systems and communities, asking:

‘Will the resource base, environment, technolo-gies and culture evolve over time in a mutually reinforcing manner?.... Will [the resource users] destroy the local resource base and environ-ment or, just as bad, the local people and their cultural system?’ (Norgaard, 1988, op. cit., p. 607).

These characterisations address the sustainabil-ity of the interactions between people and their environments over time. They refer to ‘the sus-tainability of the interactions between regions and cultural systems’ (ibid.), that is, to exchange and reciprocal transformation as a cultural as well as material process. A co-evolution, if it occurs, is a biophysical symbiosis, but it is not simply the

biophysical coexistence. Purposefulness and

meaning are located on the symbolic planes as much as the biophysical planes. This raises ques-tions such as: in what ways does a person feel part of a community, in what ways do their choices and actions depend on their sense of being part of a community?

about the uses of the wood has appeared until now; the different uses as wood cutting, walking, hunting, daffodils gathering, and so on, coexist seasonally or all year long without a major prob-lem. On the face of it, there is not a problem of defending an environmental value under immedi-ate threat. So, the valuation question is a straight-forward one of understanding what sorts of significance are attached to the forest by the local communities, whether or not this is sufficient to ensure that it will sustained and, if so, in what form?

3. Investigating the relationship between community viability and forest value

3.1. The woodland as a socio-ecological-economic unity

In early phases of the VALSE project Bois de Bouchereau study, analyses were conducted that brought out the qualities of the forest socio-eco-system as an indivisible unit. Based on both insti-tutional and ecosystems analysis, a dynamic simulation model was developed that represented the evolving forest system through the interaction of human and ecological forces (Heron, 1997; Heron and O’Connor, 1999). The model ex-pressed, as a sort of metaphor, the way that the forest is a component of a veritable ‘social in-frastructure’. A complex tissue of social meanings and economic exploitations is invested in the liv-ing whole, and the ‘value’ of the forest is insepara-ble from this collective (shared, communal) investment.

The description of the forest was thus devel-oped along two axes: the variety of actors (stake-holders) who contribute, and the variety of values attributed by these actors to the forest system. In this way a preliminary picture of the relationship between community viability and forest value is obtained (see Heron, 1997; Noe¨l and Tsang King Sang, 1997):

1. The owners. The woodland is fragmented into nearly 300 lots, distributed across about 155 separate owners, most of whom live in the nearby farming communities. Ownership is

transmitted mostly though hereditary trans-mission, which means a growing proportion of distant owners. This is private property both legally and really to some extent. The wood is exploited by owners, primarily as a source of fuel, with a smaller amount harvested for tim-ber. In terms of harvesting practices there are three classes of proprietor: type 1 does not carry out any maintenance of their woodland lots; type 2 carries out periodic clear-felling (rotation period of around 30 – 45 years); type 3 undertakes continual maintenance and selec-tive harvesting.

2. The farmers whose lands adjoin the forest. There are about 20 such farmers, the majority being around 60 years old. There are pressures on these farmers to leave some lands fallow (e.g. European agricultural policy directives), and at present the tendency is to let areas adjacent to the forest lie unproductive so that they become a sort of scrubland which is a good habitat for some forms of wildlife. 3. The hunters. Hunting is a traditional pastime

and the woodlands are privileged domains for this activity. In the district of the Bouchereau Woods there is a hunting club with nearly 100 members, made up of woodlot owners, farm-ers and a few outsidfarm-ers. Since the 1970s, the game populations have diminished markedly, due in part to isolation of the woodland and in part to illicit hunting by outsiders. Various measures are being pursued by the (also dimin-ishing) hunting community to enhance the wildlife populations while still preserving the spontaneity of the hunt.

4. Visitors on foot. The forest is greatly valued in the springtime for daffodils (including hordes who come to pick the flowers from Paris). In the past it had importance also for its contri-butions to the local cuisine: berries; mush-rooms; snails and other items in their seasons. There are many local recreational users, but there are some outsiders.

roads, and co-ordinates some replanting in consultation with the hunting club and an environmental organisation, Les Mains Vertes du Gaˆtinais, whose preoccupation is preserva-tion of the patrimoine naturel. The napreserva-tional hunting authority and the regional council both also play important roles in defining con-servation perspectives, priorities and measures for implementation.

The various categories of human actors can be understood as agents of ecosystem stability and of change. Their significance cannot be defined in-trinsically, but rather will depend on the overall state of balance — or imbalance — in the wood-land system dynamics. The variety of users and uses points to a high local significance of the woodland, associated mostly with the rural (vil-lage and agricultural) community life in the re-gion. However, this high valuation is now ‘at risk’ due to demographic and lifestyle change tenden-cies. Less and less people take an active interest in the forest. This not only suggests a ‘reduced de-mand’ for the forest values, it also means that the forest will objectively change. It is probable that the existing biological diversity (including flower-ing species, mushrooms, butterflies, birds, game animals and various species of trees) will diminish if the woodland were to be generally neglected over a long period of time. This is a reminder that the ‘values’ of this woodland are inseparable from the customary ways of life of the people involved. We are not dealing with an ‘intrinsic value’ as if it were independent of human perception; rather we are documenting the human appreciation of the richness of the forest life forms.

3.2. The sociological dimensions of enquiry into 6alue

The demographic data obtained for wood-lot owners showed that, although ownership may be transmitted mostly though hereditary transmis-sion, a process of rural depopulation is resulting in a growing proportion of distant owners. The locally resident population is growing older (for example, the majority of the 20-odd farmers whose lands adjoin the forest are around 60 years old). The preliminary diagnostic phase of

mod-elling and the demographic data thus suggested two questions for orienting further enquiry.

First there was the methodological question of

how and in what terms to assess the value of the woodland as an actual part of the local communities’ way of life.

Second, there was the forward-looking

ques-tion of the implicaques-tions for the woodland’s management of the observable demographic and lifestyle changes, especially if these latter

imply a diminution of the woodland’s

significance.

The subsequent phase of the enquiry into value was carried out through a survey process that combined a data questionnaire with depth in-terview procedures. This followed design notions of a number of earlier valuation studies (see Vad-njal and O’Connor, 1994; Spash, 1997, 2000 and in this volume) showing how it is possible to conduct a structured WTP or WTA questionnaire enquiry which, simultaneously, functions as an entre´e or framing device for an open-ended inter-view. The advantage of this approach is that it permits the queries, opinions, reactions, commen-taries, objections of the questionnaire respondent to be documented (e.g. recorded on pocket audio-cassette), so allowing the researcher to learn — through listening and subsequent discourse analy-sis — about the reasoning being applied by the respondent.

whether or not the value attached to the wood-land will be sustained into the future.

With these design notions in mind, some initial consideration was given to the possibility of con-ducting a survey enquiry into the monetary value of the woodland through posing willingness-to-pay (WTP) and willingness-to-accept (WTA) questions to members of the local communities. Conducting such a survey requires proposing (hy-pothetically) a plausible situation for the hypo-thetical bids. One option would have been to pose

WTP/WTA questions concerning availability of

the woodland as a whole. But, since the local people already have everyday use access and there is no immediate threat of destruction (such as a commercial zone or a motorway or TGV train

route), this option would have been alarmist and/

or implausible.

A less disruptive line of approach was to en-quire into the conditions surrounding the trans-mission of individual wood-lots from one owner to another. Initial investigations revealed that the wood-lots are transacted individually — mostly in the context of a hereditary transmission, some-times as a local rearrangement (e.g. a neighbour seeks an adjacent plot, or a local person seeks a hunting terrain). These changes of ownership

in-volve monetary transactions, administered

through notary offices in the district. So there is a price for a wood-lot when it changes hands. But this does not necessarily mean that there is a ‘market for wood-lots’. We have to look into the social circumstances of the transaction.

The decision was finally made to undertake a survey on the price at which and, more particu-larly, the conditions under which, existing propri-etors might be willing-to-accept sale of their plot(s). A survey format was developed that com-bined a search for some specific data and quanti-tative information together with open-ended questions that would permit an ‘in-depth inter-view’ to be developed. After an exhaustive process of enquiry (detailed in Boisvert et al. 1998), a sample of 55 owners of wood-lots (parcels) in the little forest were contacted and subsequently inter-viewed. Excluded from the enquiry, for logistic reasons, were those owners residing far away from the wood. So the enquiry sample concerned

own-ers who live in the immediate region. This is a ‘biais’, but it is not critical in relation to the primarily interpretative rather than statistical pur-poses of the study. The questionnaire was deliber-ately kept very simple, and focussed on the perception the owners have concerning the price of their own and other woodlots (see Table 1 and the Appendix A).

3.3. Profile of the sur6ey sample of Bois de Bouchereau wood-lot owners

The principal characteristics of the owner sam-ple of 55 peosam-ple who replied to the questionnaire are as described below.

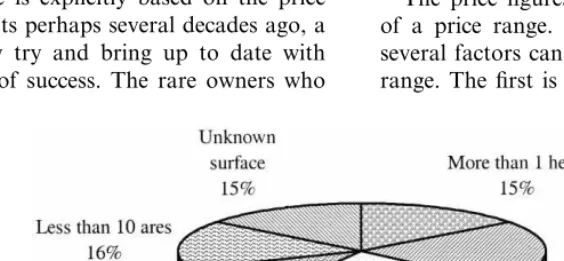

The majority of the group was male (64%). The women often declared themselves as incompetent where wood is concerned, even when the plots belonged to them either through an inheritance from their parents or the sharing of goods follow-ing a marriage. However, durfollow-ing the interviews, female partners were present, and although they often remained quiet at the outset, they partici-pated more, and at times vocally, as the interview developed. The average age of the group is fairly high (above 66 years), the youngest being 30 and the oldest 93. Age distribution is as shown in Fig. 1.

is retired while his younger wife manages the operation of the farm. It is mostly farmers or ex-farmers who hold the wooded plots of land

rather than rural notables: the Bois de

Bouchereau appears thus as an extension of agri-cultural activity.

4. The valuation enquiry findings

The results of the questionnaire combining quantitative information with ‘in depth’ interview

responses make clear how the ‘price’ of a wood-lot is associated with a transaction whose signifi-cance is far more than a ‘simple market value’. The answers and explanations offered by the in-terviewees show how each wood-lot is like a thread in the local social fabric (see Boisvert et al., 1998).

4.1. Unwillingness-to-accept

In general, the participants found it extremely difficult to imagine themselves in a position where

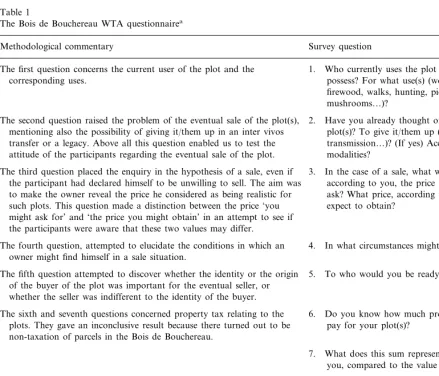

Table 1

The Bois de Bouchereau WTA questionnairea

Methodological commentary Survey question

1. Who currently uses the plot which you The first question concerns the current user of the plot and the

corresponding uses. possess? For what use(s) (woodcutting

firewood, walks, hunting, picking daffodils or mushrooms…)?

2. Have you already thought of selling your The second question raised the problem of the eventual sale of the plot(s),

mentioning also the possibility of giving it/them up in an inter vivos plot(s)? To give it/them up (inheritance, transmission…)? (If yes) According to what transfer or a legacy. Above all this question enabled us to test the

attitude of the participants regarding the eventual sale of the plot. modalities?

The third question placed the enquiry in the hypothesis of a sale, even if 3. In the case of a sale, what would be, according to you, the price that you could the participant had declared himself to be unwilling to sell. The aim was

to make the owner reveal the price he considered as being realistic for ask? What price, according to you, could you such plots. This question made a distinction between the price ‘you expect to obtain?

might ask for’ and ‘the price you might obtain’ in an attempt to see if the participants were aware that these two values may differ.

The fourth question, attempted to elucidate the conditions in which an 4. In what circumstances might you sell? owner might find himself in a sale situation.

The fifth question attempted to discover whether the identity or the origin 5. To who would you be ready to sell? of the buyer of the plot was important for the eventual seller, or

whether the seller was indifferent to the identity of the buyer.

6. Do you know how much property tax you The sixth and seventh questions concerned property tax relating to the

plots. They gave an inconclusive result because there turned out to be pay for your plot(s)? non-taxation of parcels in the Bois de Bouchereau.

7. What does this sum represent, according to you, compared to the value of your plot? The two final questions were of a more prospective nature, asking the 8. How do you see the Bois de Bouchereau in

50 years? interviewees to envisage the Bois in, say 50 years and exploring whether

it was considered possible, probable, and/or desirable for the bois de Bouchereau to be managed by people other than the current owners.

9. Do you think that people other than its current owners may eventually manage the Bois de Bouchereau?

Fig. 1. Age of participants.

would be prepared to sell are those who are indifferent to the wood because they do not live in it’s immediate vicinity and therefore no longer have the opportunity to visit it. When this disin-terest becomes absolute, the owner is often no longer known or identifiable, and any transaction with local potential buyers becomes difficult to obtain.

In sum, the parcels of forest are very strongly perceived, individually and collectively, as ele-ments of familial heritage, inherited from previous generations and passed on future generations. This fact on its own explains the scarcity of sales. The sense of ‘heritage’ is so strong that recent buyers of parcels typically adopt the same atti-tudes about the permanence of the ‘patrimony’.

4.2. The price of a wood-lot

When the question of the price of a plot was raised, the first element of comparison put for-ward by the participants is cultivatable land. In comparison, wood-lots in the Bois de Bouchereau are perceived as having little value. Half the par-ticipants had no difficulty whatsoever in giving us a price, always expressed spontaneously in terms of a value per hectare, and not in terms of the value of their own particular plot. What we have here is a transaction price, known or expected by the owners, and readily revealed to us.

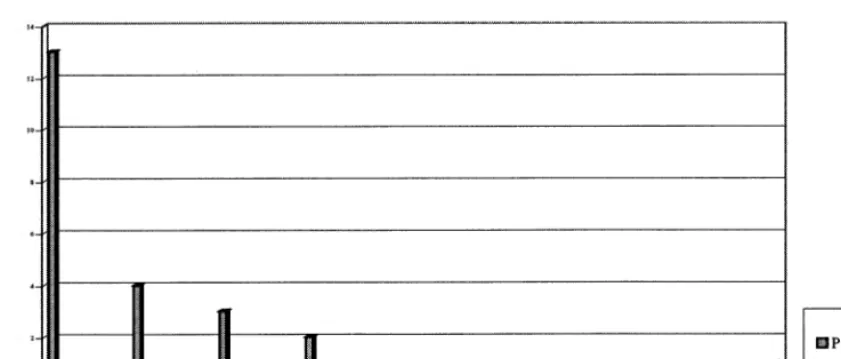

The price figures were often given in the form of a price range. According to the participants, several factors can play a role in determining this range. The first is the date of the next cut: if the they would sell their plot(s). Three participants

appeared indifferent (4%), and only six (11%) envisaged the possibility of selling. The rest (85%) refused to sell, with varying degrees of vehemence — outright refusal to sell in the case of 43 people (79% of participants). Five owners declared them-selves as recent/potential buyers.

It was generally felt that any talk of selling was indeed, hypothetical. The low number of transac-tions noted concerning the wooded plots, which are far less frequent than those concerning agri-cultural land, confirms this. Current transactions concern the resolution of an inheritance, an es-cape from joint ownership, or internal transac-tions within families which wish the wood to remain in the family patrimony.

Given the general refusal to sell, the estimation of certain people is explicitly based on the price they paid for plots perhaps several decades ago, a price which they try and bring up to date with varying degrees of success. The rare owners who

Fig. 3. Price of a wood-lot. wood of the plot is ‘ready for cutting’, the plot is

worth more than if it had just been cut. The second is the existence of a specific individual request, coming for example from a neighbour who wishes to acquire an adjacent plot or a hunter who wishes to benefit from hunting rights linked to land ownership. In these cases the price of the plot can rise. A third factor might be the ‘good quality’ of the plot, but this was not given great importance by the respondents. This quality is more likely to be translated into a shortening of the cut rotation periods.

If we retain the values explicitly given to plots whose wood is ‘ready for cutting’, the distribution is as shown in Fig. 3. (There was one very high value of 250 000 – 300 000 FF per hectare, this is probably due to a confusion (by a factor of 10) between old and new francs. We leave this ‘out-lier’ price aside.)

The person who gave the highest base value (25 000 FF) in his price range also gave the highest value of 52 000 FF for a ‘very very good wood’. Ten thousand French Francs per hectare is the value given by the greatest number (13 persons) of participants giving a pre-cise figure, though the average of all replies of a single figure is somewhat higher, at 15 720 FF per hectare.

These figures can be compared with the price range given over the telephone by notary offices

in the region. The office of Puiseaux evaluated the current price of wooded plots in the region at between 10 000 and 15 000 FF per hectare; the office of Beaumont en Gaˆtinais gave an estimate of between 8 000 and 20 000 FF per hectare. So the price ranges provided by the participants ap-pear to be realistic in the sense that they corre-spond closely to what we might call, for want of a better expression, a ‘state of the market’ for wooded plots.

What is the significance of such a price? Does this money value of the wooded plot represent an asset value? Let us consider the total revenue that might be obtained from a wood-lot. A plot of woodland is cut, on average, every 50 years. By using the known market price of firewood, we can estimate the internal rate of return of the asset that a plot in the Bois de Bouchereau assures. According to our survey participants, the maxi-mum price for a plot that has just been cut is 5 000 FF per hectare. A complete cut yields a maximum of about 260 steres per hectare, and the current firewood price is 200 FF per stere. On this basis, expected revenue for a just cut plot is 52 000 FF at 50 years hence. Thus, for an initial expenditure of 5 000 FF and a revenue of 52 000 FF in 50 years, we obtain the internal rate of return as the solution to:

this yielding an internal rate of return of r=

4,8%. (These figures do not consider the variable costs associated with harvesting, etc., of the wood.) In comparison with other investment op-portunities it is evident that, with such an internal rate of return (exclusive of management and har-vesting costs) and with such a long-term commit-ment, the holding of wood is not, in itself, economically very profitable.

4.3. What is behind the wood-lot price?

So, what drives individuals to hold on to wood-lots and, furthermore, to declare that (outside of heritage context) they will not sell them? It seems highly probable that the price of a plot reflects elements other than a simple commercial asset value. The specific circumstances of each wood-lot transaction (family transmission, consolidation of holding by local proprietors, departure of a family from the district) highlight the social relationships this community keeps up with and through this forest, thus referring back to the specific social norms, individual and collective attitudes that sus-tain and constitute the value. The survey-inter-view process has revealed how the ownership of parcels goes hand-in-hand with a particular knowledge, which extends from the historical and the folkloric through to knowledge of the exact territorial limits of the different wood-lots and the specific techniques of exploitation. This suggests that:

on the one hand, the price expresses something

more than a capitalised ‘market value’ for the wood. The price may in part reflect elements which, according to an enlarged concept of ‘economic value’, go beyond the value related to the exploitation of firewood, such as

‘recre-ational value’ and a legacy/bequest-type asset

value (cf. the notion of ‘total economic value’ developed by environmental economists such as Pearce and Turner, 1990);

on the other hand, an actual or envisaged

market price of a wood-lot cannot, even with an enlarged concept of economic value, convey fully the dimensions of the value (read: signifi-cance) accorded to the parcels of forest.

Our interview-survey process has enabled us to reveal, through the words of the participants, a variety of qualitative elements of use, social inter-action and meaning that each play a role in the overall value of the wood. Cumulatively, we ar-rive at a picture of the social processes at work in the relationship of the community with the wood, the social norms and the individual and collective attitudes which concern the wood and contribute to the determination of its value. The representa-tions that local inhabitants make of the wood — a part of family heritage, a source of collective or private use, an object of knowledge, a place of memory, etc. — all testify to the many dimen-sions of social processes that develop concerning the wood, and which are transmitted from genera-tion to generagenera-tion.

4.4. Stages in the re-constitution of 6alue

We can highlight both the sequence of the stages of the enquiry process and the sense of the different influences of the representations and of the social processes on the price, through a dia-gram with multiple levels (see Fig. 4). Three major levels can be distinguished:

At the top of the pyramid the market price is

represented, such as it was revealed by the participating owners. This price represents a quantified element as provided by the enquiry. The price appears to be a ‘tip of the iceberg’ for the complex social dimensions of value that the in-depth interviews were able to define more clearly.

At the bottom of the pyramid various elements

are indicated, such as private and/or collective

use, individual and/or community behaviour as

well as psycho-sociological characteristics and the representations grouped under the title:

Memory/Knowledge and Affective links. This

level represents the sphere of social and cogni-tive processes linked to value.

Between price and the underlying

social-cogni-tive dimension, we insert a level for ‘interpreta-tive’ filters that represent various categories

such as existence value, aesthetic and/or

categories commonly used in economic analysis of elements of natural capital, are seen to be fed by different elements from the underlying social processes level. Their inclusion works to ‘account for’ the gap between the revealed wood-lot price and the pure asset value relying on commercial wood recovery alone. The dif-ference between the right-hand side elements and the left-hand side elements is between ‘market-like’ and non-market elements — on the right the ‘asset value’ and ‘patrimony value’ elements have a clear relation to a money transaction, whereas on the left the ‘existence

value’ and ‘aesthetic/landscape value’ elements

have an essentially non-market character. The methodological significance of the diagram is that, starting from an explicit element, namely, the price for wood-lots as provided by the en-quiry, the learning during the in-depth interviews about the social processes at work on the wood allows a fuller understanding of the nature and the components of the value attributed to the

woodland and renewed/transmitted through the

woodland. As suggested by the middle layer of Fig. 4, it is possible — with a bit of artifice — to

summarise some of the valuation findings in terms of conventionally applied categories of economic environmental valuation. Thus

There is economic ‘use value’ of the wood as

fuel (though many locals currently use electric home heating), and there is an economic value, to a lesser degree, for the wood as timber. Perhaps also there is a genuine economic and not just lifestyle value of the food items to be found in the forest, though this would now be of minor significance.

The hunt may be said to be a ‘recreational

value’ (perhaps quantifiable — though we have not sought to validate this hypothesis — in terms of other opportunities foregone and the travel costs involved).

The dimensions of ‘patrimony value’

(some-times called a ‘bequest value’) and also of ‘aesthetic or landscape value’ are clearly per-ceived by the local people. Owners of wood-lots living in the district take some considerable collective pride in the existence and mainte-nance of the forest, and ownership is an impor-tant factor of social identification for the community of inhabitants.

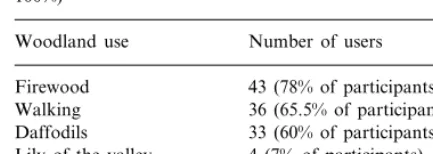

Table 2

Principal uses according to owners (total of % is higher than 100%)

Woodland use Number of users Firewood 43 (78% of participants) Walking 36 (65.5% of participants)

33 (60% of participants) Daffodils

4 (7% of participants) Lily of the valley

Mushrooms 3 (5.5% of participants)

and the plots form an integral part of family patrimony. The family lines go directly back to parents and grandparents … and to great grand parents …; and this continuity is considered in-deed to guarantee the permanent existence of the wood. There may also be a wider family clan, with cousins and nephews (this is more difficult to verify systematically). But in this case too, the wood must ‘stay within the family’, and eventu-ally an internal family transaction often allows this to happen.

5.2. The rural mentality and tradition of accumulation

The patrimonial character of wooded plot is reinforced by traditional rural attitudes concern-ing the possession of land, which consists of accu-mulating as many plots as possible without ever selling any. This helps explain why recent buyers have the same tendency to hold on to their plots as those whose plots have been in the family for generations. These two elements — the emotional character of wanting to keep the wood in the family, and the rural tendency to want to accumu-late (productive agricultural land as well as woods) — further account for the existence of the patrimonial value.

5.3. Essentially non-market uses

The wood’s uses, according to the owners we met, are divided between a principal use — the collection of firewood — and two secondary uses: visiting the wood (be it for walking or to relax or pick flowers or mushrooms) and hunting (see Table 2).

The provision of firewood for the family is, without doubt, the most common use of the wood, stated by 78% of those who responded to the enquiry. It is the only real ‘private’ use of the wood. Cutting is done on the plot or plots pos-sessed. Any crossing of boundaries during cutting is a source of conflict, which must be resolved by the intervention of a third person; for example, an older person who will come to the plot to verify plot boundaries. The wood cut is not

commer- By contrast, this is not a question of ‘intrinsic

value’ such as the variety and robustness of species independent of human perception or utilisation; rather the study has documented the human appreciation of the richness of the forest life forms.

What emerges from the enquiry as a whole is that there is only a weak linkage between the price of a wood-lot at the moment of its transmission from a former to a new owner, and the economic ‘use values’ associated with it. Some survey re-spondents did remark that a high timber quality of mature standing trees would be reflected in a higher transaction price. But this is relatively inci-dental. For the most part, both the ‘use values’ and the ‘non-use values’ (notably bequest) are outside the monetary domain. These non-market values as well as the (mostly non-market) labours of wood-lot tending and other maintenance are inseparable from the tissue of a customary way of life.

5. The non-market dimensions of the woodland value

5.1. A family heritage first and foremost

cially sold, and partial clearing and selective cut-ting prevails over the large-scale clearing of the wood for firewood. A traditional practice of bois de moitie´ (which gives half the wood cut to the cutter and half to the owner, a sort of temporary sharecropping) is still maintained, although wood-cutting by ‘pieceworkers’ is developing. A small proportion of the wood is no doubt sold, but informally.

The owners are well aware of the relation be-tween current domestic heating practices and the cutting of firewood. Home heating from wood burning alone is now almost non-existent. The quantity of wood required to heat a house accord-ing to current habits is often greater than the amount of firewood that a small plot can produce in a year. Central heating, either gas or oil, is increasingly popular. Sometimes a wood burning oven or frying pan remains (used occasionally as a back-up) and fake living room fireplaces are common. Reasons given for changing from one system to another are ease of use, easier storage,

or the cleaner nature of modern heating

systems. Yet a major factor — the fundamental transformation in agricultural practices which leaves no time or place for ‘unprofitable’ annex activities like woodcutting — goes largely unmen-tioned.

Behind firewood, a number of other practices are linked to the wood as a whole — they range from walking and enjoying the shade, to the picking of daffodils and other flowers and mush-rooms. These uses, walking, picking daffodils, appear fairly banal and were given by most of the participants in the enquiry, provided that their age and health still allowed them to visit the wood. Amongst these activities, walking is the most popular year round activity. Here also the participants, especially the old, lapse quickly into reminiscences of times past. The picking of daf-fodils is necessarily limited to the flowering sea-son, when there is a stampede. Some note that it always seems necessary to have a pretext to go to the wood: to look over the plot, to verify the boundaries, to check the state of growth, to pick flowers. For others, on the contrary, walking is a

goal in itself. Walking and flower picking take place throughout the wood, without taking prop-erty boundaries into account.

For those owners who hunt (16% of the survey participants), this activity represents an important use of the wood. Here once again there exists a separation between the plot possessed and the activity of hunting: hunting could not, in most cases, be carried out exclusively on one’s own bits of wooded land. Importantly, the possession of land in the wood is a criterion for membership of

the local hunting association of Bromeilles

(de la Gorce, 1994). Some hunters would

like to give the impression that hunting is more akin to a walk with the dog rather than an organised massacre. However the ritual element of the opening of the hunting season, with the deployment of the hunters, also has its supporters. Here too, nostalgia for past hunts and openings recurs.

5.4. An existence 6alue

For many owners the value given to the wood seems to include a strong element of something close to an ‘option value’ or existence value. They are happy that the Bois de Bouchereau exists. It is

perceived as adding variety to a rather

5.5. Indi6idual property and collecti6e management

We have observed no cleavage of behaviour or opinion between the owners of relatively large pieces of land (ten owners currently possess more than 1 hectare each) in the Bois de Bouchereau and those who possess smaller areas of land, 2 to 10 ares for example. In all cases, being an owner in the wood seems to enhance one’s social stand-ing. It enables one to take an active role in the community of Bromeilles, and, on a broader level, in the neighbouring villages. For example, for those who do not possess agricultural land, the possession of wooded plots may be a means of becoming member of the Bromeilles hunting asso-ciation, which remains a strong social element within the community.

If collective identity is important, the partici-pants remain, nonetheless, fierce supporters of private property. In response to the final question of our enquiry, which asked them to envisage collective management policies for the wood (viz. ‘Do you think that people other than its current owners may eventually manage the Bois de Bouchereau?’), only nine people felt that this was desirable, 22 replied that it would not be desirable and three felt that it depended on the extra costs generated. The general discourse showed an in-transigence of the participants regarding respect for property rights. The collective feeling concern-ing the wood does not displace the respect for individual property rights. The two dimensions are complementary and reinforcing. The free ac-cess allowed throughout almost the entire wood (only one owner has fenced his plot) and the public nature of certain activities (walking, flower-picking, etc.) ought not to lead anyone to believe that the owners are ready to abandon their prerogatives.

5.6. A shared regional heritage

The very strong sentimental attachment to the wood of some of the participants is fed by nostal-gia for past uses of the wood, those of their youth. Here can also be found legends persisting from far back in history (the role of the wood in

the Middle ages, the supposed presence of a con-struction in the centre of the wood, the existence of underground passages). Also having a clear historical dimension is real knowledge of the wood, whether it concerns identifying the plot boundaries, the memory of certain family transac-tions, maintenance and woodcutting techniques, or the historical or legendary background to the wood. This is considered by the participants as being the reserve of the older members of the community and inseparable from the patrimony. Some express very clearly the need to pass this knowledge on, at the same time as the wooded plots, from generation to generation, because ‘without the knowledge that goes with it, the wood is nothing’.

The proximity of the wood, either geographic or in terms of the role it fulfils within a family, seems to play an important role in the enhance-ment of the wood’s value. To a large extent interest or indifference in the wood is a function

of geographic distance from the owner/family

members. Outside Bromeilles and the neighbour-ing communities, it is difficult to visit the wood on a regular basis; and indifference soon sets in. This is without doubt one of the keys to the future of the Bois de Bouchereau. Departures from the region are leading to the disappearance of the historically and geographically rooted knowledge.

6. Outlook: will the woodland value be sustained?

The high value ascribed to the Bois de Bouchereau finds its basis in a culture of patrimo-nial meaning and investment. This is not just investment of effort but also, more particularly, investment with meaning. The woodland as a whole, and the bits individually, are carriers of meaning — as elements of family and communal heritage — proudly inherited from the previous generations and, as such, destined to be passed on to future generations.

hand, that most of the owners had a fairly precise idea of the monetary value of their plots and, on the other hand, that non-commercial aspects are predominant in the constitution of a value for the woods.

These are not profit-making assets and holding on to them is explained by other determinants. A sense of family heritage accounts in large part for why families hold on to their plots. In summary:

the low number of transactions is explained by

the fact that they normally take place only when resolving an inheritance or during divi-sions for ending joint ownership;

the vast majority of owners declare vehemently

that they would not sell their plots;

those who acquire plots go on to adopt the

same attitude (a reluctance to sell) as those who inherit plots;

tradition is predominant in the ownership of

plots, since ownership has survived even though the practices which supported and justified it (e.g. providing families with fire-wood and food) have greatly diminished. Beyond these generic patrimonial determinants, the enquiry was able to distinguish distinct ‘gener-ations’ of viewpoints within the community. The oldest inhabitants (more than 70 years old) look back with nostalgia at traditional uses of the wood, which for them is in progressive decline. The group of younger retired people from agricul-ture (those aged around 60) have, by contrast, turned their backs en masse on the wood and the uses associated with it, having been absorbed by the development of large-scale industrial farming (cereals, beetroot), viz. of high-productivity

mech-anised agriculture. And then, amongst the

younger generation of people who have remained to work the land, we now find some who attach a strong symbolic importance to the wood and de-clare themselves as potential buyers of plots.

Yet, the sustaining of the forest value into the future is by no means assured. If, in the patrimo-nial tradition, the tending of the forest is a sort of metaphor for the maintaining of human commu-nity, it also follows that both forest and human community are vulnerable to neglect, decay and decline. The majority of the owners interviewed

believe in the durability of the Bois de

Bouchereau. But they have some difficulty to imagine it as being any different than its present appearance. For example, they do not analyse acutely, or they do so in contradictory ways, the links between the currently practised forestry techniques, changing patterns of non-timber use, and the evolution of the woodland’s characteris-tics, among others, its recreational interest, scenic qualities and internal accessibility. They do not yet discuss (or, at least, not openly) the uncertain future of the highly-mechanised and subsidised regime of agricultural production (notably, the European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy). All these elements point to a clear link between the evolution of the wood and vicissitudes of French rural society in general. Departure to the towns for most (though not all) of the young generation has brought in its wake a loss of familiarity and knowledge linked to the wood, a loss which can go as far as total ignorance regard-ing the boundaries of the plots.

In the patrimonial tradition, the investments of time, thought and effort in wood-lot maintenance, trail clearing and replanting (and so on) are in-vestments in a social whole. These are largely traditional practices that, for the most part, have been based on a communal logic of reproduction and renewal rather than a logic of individual interest and profit. Put in other terms, the individ-uals’ interests and evaluations are conditioned by the social whole. Their ‘preferences’ are recipro-cally sustained through the shared meanings and activities sustained within the local communities.

Yet, this patrimonial tradition may be weaken-ing, and the forest value with it. In view of the ageing and diminishing economic vigour of the community of interested local users and owners, the local socio-economic basis for maintenance of the woodland may be at risk. The risk can be appraised in the following terms. As the local population ages and diminishes, the number of persons active in wood-lot and pathway mainte-nance may fall. (Community leaders in the district have, spontaneously, expressed concerns of this sort.)

This risk can be expressed in the following way. Suppose, hypothetically, that the option be ex-plored of having an external agency assume some of the responsibilities for maintaining the wood-land as an amenity value. Can it be expected that the ‘demand’ for the forest values will be high enough to justify the expense? Will a new genera-tion of owners/users, not having the same sorts of communal roots, be willing to pay money (through, for example, taxes or access fees paid to the local or regional authorities?) in scale equiva-lent to the embodied-time willingness-to-pay of the traditional owners? Suppose not. A standard economist’s form of explanation would be that the new aggregate WTP is lower than in the past because, in aggregate, the population’s prefer-ences have changed — that is, the demand for the forest values is lower than before. A different form of explanation, in keeping with the patrimo-nial tradition, would be that the forest-community symbiosis as a structure of lived and shared mean-ing (and a form of local economic life) has died out.

Both forms of explanation may be allowed. Their relative pertinence depends partly on the theoretical reference points preferred, and this in turn is connected to the visions held about possi-ble and desirapossi-ble futures in the French society. Is the cost-benefit appraisal or the patrimonial tradi-tion the more relevant perspective for helping to decide about agricultural policies, rural and re-gional development goals, and nature conserva-tion policies? The Bois de Bouchereau case study has not tried to give the definitive answer to this question, but does give some indications about how it may intelligently be posed.

7. Concluding remarks

In part, the argument of this paper is a version of an old quarrel of welfare economics concerning the inseparability of allocative (efficiency) and distributional (equity) goals (see Samuels, 1992a,b Martinez-Alier and O’Connor, 1996; O’Connor, 1997a,b). However, we give a particular slant and meaning to this debate. First, we insist that the further that concerns of environmental policy ex-tend to the long-term future, the more will

inter-temporal distributional — and, thus,

sustainability — considerations need to

predomi-nate over allocative efficiency in policy

appraisal. Second, we insist that the further

that concerns for environmental values

extend into the domains of aesthetic and cultural as well as economic appreciation of natural cycles and systems, the more difficult it becomes to apply (or justify) the assumptions of value-commensurability and substitutability that

under-lie conventional economic valuation

methodology.

TheVALSE project as a whole has highlighted the multi-dimensionality of environmental valua-tion problems (O’Connor, 2000). Many

land-scapes and ecosystems, with their

multiple ‘environmental functions’, are like in-frastructures whose ‘value’ is bound up in the whole complex of activities that they support. The process of identification of alternative uses and their benefits and costs is inseparable

from the question of the distinct (though

often inter-dependent) communities of interest to be, or not to be, sustained. It is in this sense that we focus on the attribution of ‘value’ to a socio-ecological economic whole, and the trans-mission (or loss) through time of this attributed value.

under observation (see Godard and Laurans, 1997, 1998, 2000; Noe¨l and Tsang King Sang, 1997). Different groups of a society may hold conflicting views about relevant justifications. A successful valuation study requires that the ana-lysts identify and interpret the concerns of actors in multiple ways. Public policy then requires not just social scientific inputs based on learning about the nature of the social situation, but also some sort of procedures for addressing the diver-gences of justification that may present them-selves. Which propositions about things that are important will be sustained as values transmitted into the future?

Optimal choice, in the neoclassical sense of searching a ‘highest-value’ use of a resource, re-quires, at some level or other, the application of a single principle for ordering, judging, and ranking what is right and best. But ‘sustainability’ in its

general social-economic-ecological acceptance,

signals the requirement to accommodate

a multiplicity of different ordering principles. For many people it involves a cherishing of the rich-ness of living with and living in nature with its variety of life forms. Market-type valuations are based on a logic of rational exploitation of an external domain (the free gifts and services of nature), and on a similarly utilitarian attitude towards others as fellow economic agents (pro-ducers, traders and consumers, and police, recon-ciled contractually in a general equilibrium). Valuation practices within the context of sustain-ability concerns start from the requirement to identify, and choose between, different possibili-ties of reconciliation and the experience of possi-ble symbioses — a decision process much deeper and more complex than a rational contractual form.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from the DG-XII of the European Commission

under contract ENV4-CT96-0226 for the

project ‘Social Processes for Environmental Valu-ation: Procedures and Institutions for Social Val-uations of Natural Capital in Environmental

Conservation and Sustainability Policy’ (The VALSE Project). Thanks to C3ED colleagues Christophe Heron, Vale´rie Boisvert and Jean-Marc Douguet for their contributions to the VALSE research on the woodland, and also our project partners from the UK, Spain and Italy. Comments from Professor Adamowicz helped us to focus the paper. Responsibility for opinions expressed, and for any faults, is the authors’ alone.

Appendix A. The Bois de Bouchereau Wood-lot owner’s Survey

I. Basic wood-lot data questions

1. Are you an owner of one or more plots in the Bois de Bouchereau?

yes/no

If it is not yourself, is it your spouse or a member of your family who is the owner? yes/no

2. How many plots do you have in the Bois de Bouchereau?

Number do not know

How big is it/are they? exact size

approximate size no idea

II. Specific Questions

1. Who currently uses the plot which you possess?

Yourself family members others (specify) do not know are not interested everybody (free access)

For what use(s) (woodcutting firewood, walks, hunting, picking daffodils or mushrooms…)?

2. Have you already thought of selling your plot(s)?

To give it/them up (inheritance, transmission…)?

According to what modalities?

3. In the case of a sale, what would be, according to you, the price that you could ask? What price, according to you, could you expect to obtain?

4. In what circumstances might you sell?

5. To who would you be ready to sell? family member

Neighbour Acquaintance

person from outside the area person from the village person from the region

local council or other local/regional bodies

6. Do you know how much properly tax you pay for your plot(s)?

yes/no exact sum Estimation

7. What does this sum represent, according to you, compared to the value of your plot? Little

a great deal Other

8. How do you see the Bois de Bouchereau in 50 years?

9. Do you think that people other than its current may eventually manage the Bois de Bouchereau?

Is there a risk that it could happen? According to you is it desirable?

Do you have anything to add? Is there

anything you would like to say that was not in the questionnaire?

References

Blandin, P., 1996. Commentaires sur l’article de C. Girard et D. Baize. Nature Sciences Socie´te´s 4 (4), 324 – 326. Blandin, P., Arnould, P., 1996. Devenir des ıˆlots boise´s dans

les plaines de grande culture: l’exemple du Gaˆtinais nord-occidental. Rapport final, CNRS, Programme interdisci-plinaire Environnement, Vie et Socie´te´s, Programme the´matique syste`mes e´cologiques et actions de l’homme, March

Boisvert, V., Noe¨l, J.-F., Tsang King Sang, J., 1998. Le Bois de Bouchereau: re´sultats d’une enqueˆte aupre`s des propri-etaires, Rapport de Recherche, C3ED, Universite´ de Ver-sailles-St Quentin en Yvelines, pp. 40

Dubien, I., 1993. Devenir des Ilots Boise´s du Gaˆtinais Nord Occidental, Research Essay (me´moire de DEA), UFR d’E-conomie, Universite´ de Paris I, France.

de la Gorce, L., 1994. Homme/Biodiversite´: l’impact des coupes forestie`res sur la richesse floristique d’un ıˆlot boise´ en plaine de grande culture, Research Essay (maıˆtrise), UFR de Ge´ographie, Universite´ de Paris I, France. Girard, C., Baize, D., 1996. Niveaux d’organisation et

ecosys-te`mes: exemple des ıˆlots boise´s en terroirs circulaires en Gaˆtinais. Nature Sciences Socie´te´s 4 (4), 310 – 322. Godard, O., Laurans, Y., 1997. Valuation Processes Taken as

Tests of Legitimacy in a Plurality of Legitimacy Orders. Research Report prepared by CIRED/AScA under sub-contract to C3ED. I. Environmental valuation as social co-ordination devices within controversial contexts. In: Proceedings of the Symposium on Environmental Valua-tion, Vaux de Cernay, October.

Godard, O., Laurans, Y., 1998. Valuation Processes Taken as Tests of Legitimacy in a Plurality of Legitimacy Orders. Research Report prepared by CIRED/AScA under sub-contract to C3ED. II. Applications to Water Resources in France, April.

Godard, O., Laurans, Y., 2000. Environmental valuation as social co-ordination devices within controversial contexts. In: O’Connor, M. (Ed.), Environmental Evaluation. In: International Library of Ecological Economics, vol. 1. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

Heron, C., 1997. La repre´sentation syste´mique de l’ilot boise´: vers une mise en evidence de la valeur sociale. Revue Internationale de Syste´mique 11 (2), 147 – 175.

Heron, C., O’Connor, M., 1999. Forest value and the distribu-tion of sustainability: valuadistribu-tion concepts and methodology in application to forest islands in agricultural zones in France. In: Roper, C.S., Park, A. (Eds.), The Living Forest, Non-Market Benefits of Forestry. The Stationery Office, London, UK, pp. 99 – 107.

Linglard, M., 1992. Les ıˆlots Forestiers en Zone de Grande Culture: Choix du Gaˆtinais Occidental, Typologie et e´chantillonnage en vue d’e´tablir leur Origine Relictuelle ou de Ne´oformation. Me´moire de Maıˆtrise CGEN. Universite´ de Paris, Paris, France.

Exem-ple du Gaˆtinais occidental. PhD thesis, Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris.

Martinez-Alier, J., Munda, G., O’Neill, J., 1999. Commen-surability and compensability in ecological economics. In: O’Connor, M., Spash, C. (Eds.), Valuation and the Envi-ronment: Theory, Method and Practice. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham chapter 2, pp.37 – 58.

Martinez-Alier, J., O’Connor, M., 1996. Economic and Eco-logical Distribution Conflicts. In: Costanza, R., Segura, O., Martinez-Alier, J. (Eds.), Getting Down To Earth: Practi-cal Applications of EcologiPracti-cal Economics. Island Press, pp. 153 – 184.

Noe¨l, J.-F., Tsang King Sang, J., 1997. Le Bois de Bouchereau: des perceptions sociales a` la mise en perspec-tive de la valeur. Cahiers du C3ED No.97-01, Universite´ de Versailles-St Quentin en Yvelines, October.

Norgaard, R.B., 1988. Sustainable Development: a co-evolu-tionary view. Futures 20, 606 – 620.

Norgaard, R.B., 1994. Development Betrayed: The End of Progress and a Coevolutionary Revisioning of the Future. Routledge, London, UK.

O’Connor, M., 1997a. Environmental valuation from the point of view of sustainability. In: Dragun, A.K., Jakobsson, K. (Eds.), Sustainability and Global Environmental Policy: New Perspectives. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham chapter 8, pp. 149 – 178.

O’Connor, M., 1997b. Reconciling economy with ecology: environmental valuation from the point of view of sustain-ability. In: Boorsma, P., Aarts, K., Steenge, A. (Eds.), Public Priority Setting: Rules and Costs. Kluwer, Dor-drecht chapter 8, pp. 139 – 162.

O’Connor, M., Martinez-Alier, J., 1997. Ecological distribu-tion and distributed sustainability. In: Faucheux, S., O’Connor, M., van der Straaten, J. (Eds.), Sustainable Development: Concepts, Rationalities and Strategies. Kluwer, Dordrecht chapter 2, pp. 33 – 56.

O’Connor, M., 2000. Pathways for environmental evaluation: a walk in the (Hanging) Gardens of Babylon, Ecological Economics 34(2) 175 – 193.

Sachs, I., 1980. Strate´gies de l’E´ code´veloppement. Les Editions Ouvrie`res, Paris.

Sachs, I., 1984. De´velopper les champs de planification, UCI: Development and Planning. Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, Cambridge University Press, Paris, Cambridge, p. 1987 English translation by Peter Fawcett.

Samuels, W., 1992a. Essays on the Economic Role of Govern-ment. In: Fundamentals, vol. I. Macmillan, London. Samuels, W., 1992b. Essays on the Economic Role of

Govern-ment. In: Applications, vol. II. Macmillan, London. Spash, C.L., 1997. Ethics and environmental attitudes: with

implications for economic valuation. Journal of Environ-mental Management 50, 403 – 416.

Spash, C.L., 2000. Contingent Markets as a Research Method into Environmental Values and Psychology. In: O’Connor, M. (Ed.), Environmental Evaluation. In: ILEE series, International Library of Ecological Economics, vol. 1. Edward Elgar Publishing, Chelten-ham.

Vadnjal, D., O’Connor, M., 1994. What is the value of Rangi-toto Island? Environmental Values 3, 369 – 380.