Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 18:55

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Professional student organizations and

experiential learning activities: What drives

student intentions to participate?

Laura Munoz, Richard Miller & Sonja Martin Poole

To cite this article: Laura Munoz, Richard Miller & Sonja Martin Poole (2016) Professional student organizations and experiential learning activities: What drives student intentions to participate?, Journal of Education for Business, 91:1, 45-51, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1110553

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1110553

Published online: 01 Dec 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 30

View related articles

Professional student organizations and experiential learning activities: What

drives student intentions to participate?

Laura Munoza, Richard Millera, and Sonja Martin Pooleb

aUniversity of Dallas, Irving, Texas, USA;bUniversity of San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA

ABSTRACT

Experiential learning theory has been referenced as a possible method for attracting and retaining members in student organizations. In a survey, undergraduate students evaluated a variety of organizational features pertaining to their intention to participate in professional student organizations. The study found that students value activities that involve professional development and contact with professionals. Age was negatively related to student intent to participate. In addition, ethnicity and being afirst-generation college student were not significant predictors in participating in a professional student organization. To enhance membership recruitment and retention efforts, educators should focus their efforts on experiential activities that enable student-faculty contact, career exploration, and skill development.

KEYWORDS

business education; entrepreneurship; experiential learning activities; professional development; student organizations

Business students often join campus organizations for the opportunity to develop presentation and interview-ing skills, network with professionals, locate internships, and gain entrepreneurial experience (Peltier, Scovotti, & Pointer,2008). These organizations implicitly promise to provide students the skills that employers expect from graduates. By the same token, employers expect that recent graduates have an applied knowledge of strategic and tactical activities and entrepreneurial and venture experience (Scott,2013). Thus, membership in a profes-sional student organization (PSO), in addition to the aforementioned skills, allows students to make connec-tions across diverse courses, meaningfully synthesize concepts, apply ideas from one context to another, and gain experiences. However, a gap exists as students join PSOs to gain wider experience, as membership often fails to meet their expectations (Peltier et al.,2008).

Given both the benefits and issues, faculty advisorsfind it difficult to recruit and retain active members (Clark & Kemp,2008; Vowels,2005). Providing the advisors with a better understanding of how to improve PSOs is important as they play a critical role in motivating students to join and remain active in the PSO, directing their campus and community activities, and ensuring that students adhere to the requirements set by their institution and the organiza-tion’s corporate office (American Marketing Association, 2013). One potential source of improving this situation is the exploration of how different pedagogies might infl u-ence PSOs and curricula (Peltier et al., 2008). A recent

study brought forth this same issue by addressing the importance of PSOs as a source of experiential learning (Serviere-Munoz & Counts, 2014). In addition, there is a lack of detailed information about organizational features that attract students (Clark & Kemp,2008). Tofill this gap, the intent of this study is to empirically determine the importance of experiential learning activities in under-standing how to effectively build and sustain collegiate chapters of PSOs with the aim of improving the value and experiences for students and faculty advisors. Specifically, the study identifies the experiential learning activities that impact intention to be active members in PSOs and pro-vides practical guidance for faculty advisors.

This manuscript is organized as follows:first, a litera-ture review offering an overview of experiential learning activities is provided. Then, hypotheses development is presented followed by a data analysis section. Last, a practical discussion of the results along with closing thoughts concludes this manuscript.

Conceptual framework

Experiential learning theory

The conceptual framework for this study is anchored in experiential learning theory, which may increase organiza-tional membership recruitment and participation by helping students recognize the value in being active in PSOs. Experi-ential learning theory is a well-known approach that is

CONTACT Laura Munoz lserviere@udallas.edu University of Dallas, College of Business, 1845 E. Northgate Drive, Anselm 101, Irving, TX 75062, USA. © 2016 Taylor and Francis Group, LLC

2016, VOL. 91, NO. 1, 45–51

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1110553

believed to go beyond the classic boundaries of a classroom or disciplinary area (Bobbitt, Inks, Kemp, & Mayo,2000) by providing students with a better understanding of the world when combined with critical thinking approaches (Petkus, 2000) by involving learning from experience or learning by doing (Dewey,1938). Over the last century, many scholars have explored the role of context and experience in learning in both formal and informal settings (Bruner,1960; Dewey, 1938; Kolb,1984). Ideas about the role of experience in the learning process underscore many approaches to learning in American higher education, including service learning, living learning communities, and study abroad/away (Bar-ber,2012), as well as having served as the theory of action for numerous management education initiatives (Forman, 2006; Hunt & Madhavaram,2006;McCarthy & McCarthy, 2006). Kolb provided the central reference point for the experiential learning theory scholarship. In a frequently ref-erenced model influenced by the work of other theorists including John Dewey, Kurt Lewin, and Jean Piaget, Kolb proposed that experiential learning is defined as“the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. Knowledge results from the combinations of grasping and transforming experience”(p. 41).

The concept recognizes that students’ past experiences, including those outside the formal classroom,figure promi-nently in the learning process and that they learn most effec-tively when they have a “direct encounter with the phenomena being studied rather than merely thinking about the encounter, or only considering the possibility of doing something about it”(Borzak,1981, p. 9). The theory includes many experiential learning activities that can be incorpo-rated into a PSO’s toolkit such as contact with professionals, interpersonal skill development, professional development exposure, networking, and entrepreneurial activities.

The applied nature of business education makes it suitable for the implementation and use of experiential learning theory pedagogies (Kolb, Boyatzis, & Maineme-lis, 2001; McCarthy & McCarthy, 2006; Osland, Kolb, Rubin, & Turner,2007; Saunders,1997) and is endorsed and advocated by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). In AACSB’s recent revi-sion to its standards, it urged business schools to increase experiential learning activities in curriculum and place emphasis on the role of extra-curricular activities, such as membership in PSOs, to increase student exposure to real-world experience (Association to Advance Colle-giate Schools of Business, 2013). In addition, Clark and Kemp (2008) argue that this theory can be used to better understand and improve student retention, involvement, and commitment in PSOs, which are an excellent source for such activities (Serviere-Munoz & Counts,2014).

It becomes clear then that experiential learning the-ory, when operationalized through experiential learning

activities, provides a framework for strengthening PSO membership. However, despite its apparent relevance, studies have not included a measurement of students’ implicit value toward experiential learning into their research designs. For this reason, this study evaluates students’intentions to participate in PSOs.

Expectancy theory

Expectancy theory (Vroom, 1965) seems to provide a rationale as to why students might be motivated and thus intent to participate in PSOs. It proposes that indi-viduals will show a tendency to allocate their limited time and energy to actions for which a positive outcome will be achieved (Buchner, 2007; DeNisi & Pritchard, 2006). Specifically, individuals engage on a series of causal events. The initial event occurs when the individ-ual forms the action-to-result connection where he or she creates expectations about the results that his or her efforts (actions) will produce. Then, a result-to-evalua-tion connecresult-to-evalua-tion is formed where, depending on the results generated, the individual creates expectations on how favorably will the results be judged. Third, the eval-uation of results is expected to also lead to positive out-comes. Last, the outcome-to-satisfaction connection is created where the expectation is that the outcomes infl u-ence personal satisfaction (Buchner, 2007; DeNisi & Pritchard,2006).

To decide among the options available to an individ-ual to behave, Vroom (1965) proposed that an individindivid-ual will select the choice that contains the most motivational force, which is expressed by the equation:

Motivational Force Dexpectancy£instrumentality£valence:

Expectancy refers to the likelihood that the individual’s effort will lead to attaining certain outcomes. Instrumental-ity addresses the belief that if the individual meets perfor-mance expectations then a greater reward will be received. Valence accounts for the actual value or worth the individ-ual places in the reward or outcome. The theory holds that it is essential that the outcome be positive or attractive as that will motivate individuals to attain it (Vroom,1965). In sum, individuals are presented as active, thinking, and pre-dicting entities that not only judge the outcomes of their behavior but also judge (subjectively) whether their actions will take them to those outcomes (DeSanctis,1983).

Hypotheses

As discussed in the previous section, the literature indi-cates that experiential learning is an integral part of the 46 L. MUNOZ ET AL.

offering among successful PSOs (Clark & Kemp, 2008; Forman,2006; Hunt & Madhavaram,2006; McCarthy & McCarthy, 2006; Serviere-Munoz & Counts, 2014). Drawing from the notion that real-world experiences will make members more active and satisfied with their orga-nization experience, it is proposed that the application of experiential learning activities in PSOs will lead to an increase in student participation while providing addi-tional learning experiences (Clark & Kemp, 2008) such as hands-on experience, interpersonal skills develop-ment, and networking skills (Serviere-Munoz, 2010). A further point is that these activities can become attractive enough that influence behavior as denoted by expectancy theory (Vroom,1965). If the studentsfind these activities to be sufficiently attractive that warrant the effort (expec-tancy), lead to a positive belief in outcome (instrumental-ity), and are valued (valence), then that empowers advisors to offer an enhanced educational experience.

The experiential activities tested were contact with professionals (activities focused on interactions with future colleagues, members of the student’s profession), interpersonal skills (the skills used to interact with one another in every day; life skills), professional develop-ment (learning activities situated in practice which do not have to be area specific as they can focus on enrich-ing an individual’s overall professional or working life), networking (activities centered around developing rela-tionships), and entrepreneurial activities (starting up and managing an individual’s own business). Thus, we pro-posed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1(H1): Contact with professional activities will positively influence the intention to partici-pate in professional student organizations.

H2: Interpersonal skill activities will positively infl u-ence the intention to participate in professional student organizations.

H3:Professional development activities will positively influence the intention to participate in profes-sional student organizations.

H4:Networking activities will positively influence the intention to participate in professional student organizations.

H5:Entrepreneurial activities will positively influence the intention to participate in professional student organizations.

Method

Data collection

The data for this study were collected from a southern state university where several PSOs are offered within

the college of business. Participants were asked to volun-tarily answer the surveys. In an effort to capture a diverse and representative sample, the data collection covered classes from several business disciplines, such as accounting, marketing, management, and finance. The sample contains the answers of 242 participants of which 51.2% (124) were men and 48.8% (118) were women. Ethnicities were represented follows: 48.3% (117) Cauca-sian, 43.0% (104) Hispanic, 4.1% (10) African American, 2.9% (7) Asian, and 1.7% (4) marked their ethnicity as other. Most of the respondents were younger millennials between the ages of 18 and 29 years old, 93.8% (227). The remaining 6.2% (15) accounts for those between 30 and 34 years old. Most of the sample worked either part time, 50.2% (121) or full time, 27.2% (66), and 30.9% (75) constitutedfirst-generation college students.

Measures

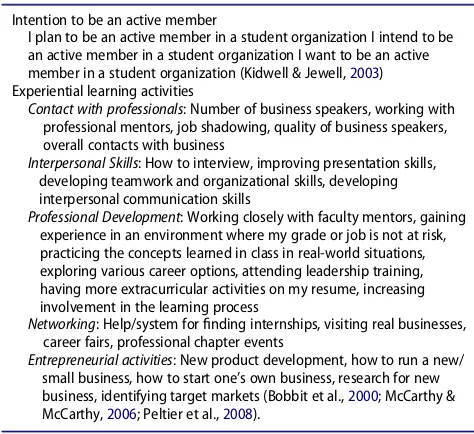

The intention to participate in PSOs was assessed using the scale developed by Kidwell and Jewell (2003), which ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Regard-ing experiential learnRegard-ing theory and its different activi-ties, items originally developed by Serviere-Munoz and Poole (2014) on how to measure experiential learning, as shown in Table 1, were employed. Participants were asked the following:

Let’s talk about participation or thinking about being an active member in a student organization. On a scale of 1–5, please indicate how important are each of the fol-lowing factors when you think about being an active member in a student organization.

The items are depicted inTable 1.

Table 1.Scale items.

Intention to be an active member

I plan to be an active member in a student organization I intend to be an active member in a student organization I want to be an active member in a student organization (Kidwell & Jewell,2003) Experiential learning activities

Contact with professionals: Number of business speakers, working with professional mentors, job shadowing, quality of business speakers, overall contacts with business

Interpersonal Skills: How to interview, improving presentation skills, developing teamwork and organizational skills, developing interpersonal communication skills

Professional Development: Working closely with faculty mentors, gaining experience in an environment where my grade or job is not at risk, practicing the concepts learned in class in real-world situations, exploring various career options, attending leadership training, having more extracurricular activities on my resume, increasing involvement in the learning process

Networking: Help/system forfinding internships, visiting real businesses, career fairs, professional chapter events

Entrepreneurial activities: New product development, how to run a new/ small business, how to start one’s own business, research for new business, identifying target markets (Bobbit et al.,2000; McCarthy & McCarthy,2006; Peltier et al.,2008).

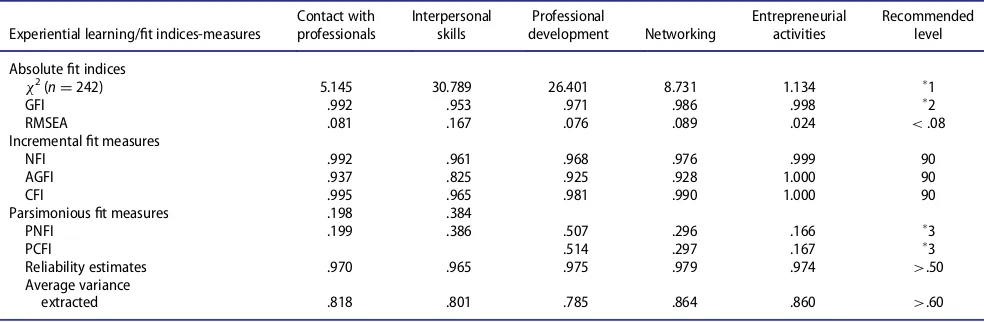

Before proceeding with the analysis, the structure of the proposed scales was validated using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for each experiential activity scale: contact with professionals, interpersonal skills, profes-sional development exposure, networking activities and entrepreneurial activities. Overall, the CFAs confirmed the scale structure for allfive activities with acceptablefit indices as can be seen in Table 2. These fit indices are within the suggested ranges as suggested by Bagozzi and Yi (1988), Hair, Tatham, Anderson, and Black (1998), and Hu and Bentler (1999). Convergent validity for each construct was assessed by examining the average vari-ance extracted (AVE) values. All of the values exceeded the 0.5 level considered to be acceptable (Chin, 1998; Chin, Marcolin, & Newsted,2003). Composite reliability values for all variables were above the recommended 0.6 level as well (Chin,1998). Fit indices, AVE, and compos-ite reliability values are included inTable 2.

Cronbach’s alpha for the experiential learning activi-ties were also assessed denoting acceptable ranges. The alpha values were .882 for contact with professionals, .876 for interpersonal skills, .883 for professional devel-opment exposure, .854 for networking activities, and .913 for entrepreneurial activities. Multicollinearity was assessed by a visual examination of the correlation matrix, as shown inTable 3, and the variance inflation factors (VIFs). The visual examination is considered a good initial assessment for multicollinearity where values above .90 denote high multicollinearity levels (Hair et al., 1998). The examination showed all levels being below .90. Next, the VIFs were examined for all of the activities being as follows: 2.728 for contact with professionals, 4.727 for interpersonal skills, 3.134 for professional development exposure, 4.258 for networking activities, and 1.971 for entrepreneurial activities. The values do

not denote a high degree of collinearity among the inde-pendent variables (Hair et al., 1998) as they are below the threshold of 10 threshold. A value over 10 suggests a serious multicollinearity problem requiring further investigation (Kutner, Nachtsheim, Neter, & Li,2004).

Results

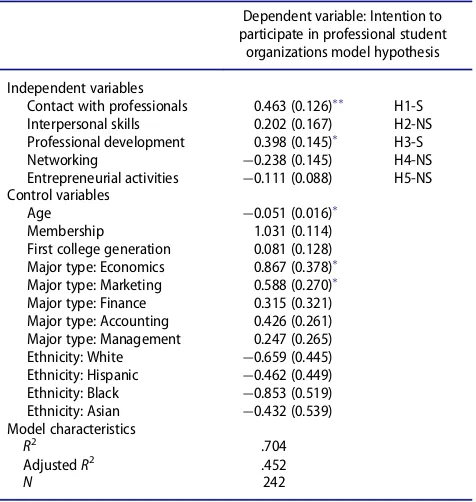

A linear regression analysis was conducted to examine the influence of experiential learning activities on inten-tion to participate in professional student organizainten-tions. The overall R2; for the model was .704 and the adjusted

R2; was .452. Control variables were also included as part of the analysis. These variables were: membership in pro-fessional organizations, ethnicity, major type,first gener-ation college student, and age. Being a member in an organization was a significant positive predictor (b D .453; p< .01) on intention and only those majoring in

economics (bD .146;p<.05) or marketing (b D.215;

p < .05) positively influenced intentions to participate

(major type). Ethnicity (accounted as Caucasian, His-panic, African American, Asian, and other) along with being afirst-generation college student did not show any significant influence on intention. Age was a significant negative predictor (bD ¡.158;p<.05).

Regarding the significant experiential activities, con-tact with professionals (bD .291; p< .01) and

profes-sional development activities (b D .232; p < .05) were

significant predictors of intention thus supporting Hypotheses 1 and 3. Interpersonal skills (b D .126;

p>.10), networking activities (bD ¡.163;p>.10), and

entrepreneurial activities (bD ¡.085;p>.10) were

non-significant experiential activities, thus not supporting Hypotheses 2, 4, and, 5 respectively. The results are sum-marized inTable 4.

Table 2.Experiential learning activities: Confirmatory factor analysis results.

Experiential learning/fit indices-measures

Contact with professionals

Interpersonal skills

Professional

development Networking

Entrepreneurial activities

Recommended level

Absolutefit indices

x2(nD242) 5.145 30.789 26.401 8.731 1.134 1

GFI .992 .953 .971 .986 .998 2

RMSEA .081 .167 .076 .089 .024 <.08

Incrementalfit measures

NFI .992 .961 .968 .976 .999 90

AGFI .937 .825 .925 .928 1.000 90

CFI .995 .965 .981 .990 1.000 90

Parsimoniousfit measures .198 .384

PNFI .199 .386 .507 .296 .166 3

PCFI .514 .297 .167 3

Reliability estimates .970 .965 .975 .979 .974 >.50

Average variance

extracted .818 .801 .785 .864 .860 >.60

1DSample-dependent statistic. Marginal acceptability.2DHigher values indicate betterfit. No established thresholds.3 Used only when comparing models.

Figures included just for informative purposes. AGFIDadjusted goodness offit index; CFIDcomparativefit index; GFIDgoodness offit index; NFIDnormed fit index; PNFIDparsimonious normedfit index; PCFIDparsimonious comparativefit index; RMSEADroot mean square error of approximation.

48 L. MUNOZ ET AL.

Discussion and conclusions

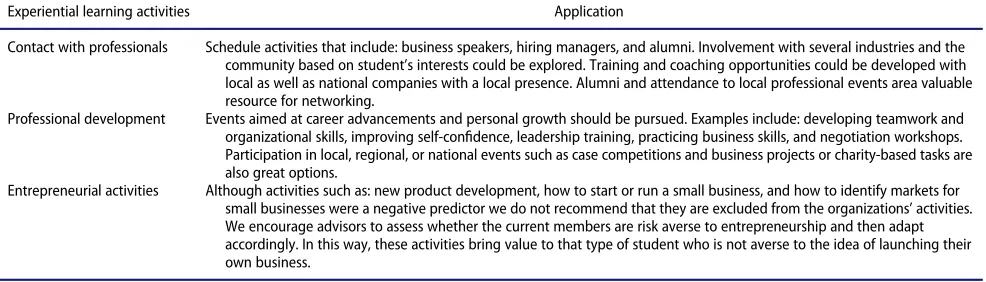

Faculty advisors to PSOs oftenfind it difficult to attract and retain students (Clark & Kemp,2008; Vowels,2005). To address the need for research that investigates how recruitment and retention can be improved, we investi-gated the impact offive experiential learning activities on a student’s intent to join a PSO. The results support an approach where PSOs focus on offering activities that involve professional development and contact with pro-fessionals as part of their activities. Contact with profes-sionals was the leading variable in the analysis. Greater student intention to participate can be expected if busi-ness speakers are regularly scheduled and students have access to professional mentors and opportunities such as job shadowing or question and answer sessions. Contact with professionals, such as training and coaching oppor-tunities, denotes that students are looking for frequent contact with businesses and professionals as they value these interactions; thus, they should be employed and promoted as part of the benefits of joining a PSO.

Additional benefits that can be promoted are affirmation of professional competence after students have com-pleted a job shadow experience or project, building, training, and practicing leadership and managerial skills. Exposure to professionals, whether one-on-one or in professional events and projects, can also lead students to build a professional network to launch their careers.

The second leading factor was professional develop-ment, indicating students have a strong preference for activities, such as interacting with faculty mentors, exploring career options, and participating in trainings and extracurricular activities, that could not only increase knowledge and skills but be also listed on the student’s resume. An excellent opportunity would be having students conduct small to medium sized projects for local businesses such as a service gap audit, a process analysis, or a marketing plan. These projects provide multiple benefits, as they are a source of differentiation and value added for the PSO, while also being a source of satisfaction for the students. In addition, the students would be able to include such projects on their resumes, while working in a safe environment where neither a grade nor a job is at risk. Faculty advisors can also benefit from the projects by using them as a recruitment and retention tool by advertising professional development opportunities. These benefits also extend to the college level as these activities can be reported as part of the engagement requirement in the most recent AACSB standards. To aid faculty mentors to promote recruit-ment and participation in their PSOs,Table 5offers spe-cific activities per area included in this study.

In addition to the results discussed about experiential learning activities with intention to participate, it is wor-thy to discuss the role that intention has on actual behav-ior. A potential explanation is that the underlying cause for intentions to be significantly impacted by these activi-ties is that students expect great rewards from a student organization and thus this motivates them to be active members. This rationale would be consistent with expec-tancy theory. It may appear then that setting proper expectations to maintain a student’s motivation could significantly contribute not only to intention to partici-pate but also to recruiting. Therefore, as the theory pro-poses, the students must believe that there is a great chance that their efforts will lead to attaining the Table 3.Experiential learning activities: Correlation matrix.

Interpersonal skills Interpersonal skills Networking skills Contact with professionals Professional development Entrepreneurial activity

Networking skills .838 —

Contact with professionals .731 .760 —

Professional development .780 .729 .659 —

Entrepreneurial activity .584 .565 .555 .614 —

Table 4.Experiential learning regression results.

Dependent variable: Intention to participate in professional student

organizations model hypothesis

Independent variables

Contact with professionals 0.463 (0.126) H1-S

Interpersonal skills 0.202 (0.167) H2-NS Professional development 0.398 (0.145) H3-S

Networking ¡0.238 (0.145) H4-NS

Entrepreneurial activities ¡0.111 (0.088) H5-NS

Control variables

Age ¡0.051 (0.016)

Membership 1.031 (0.114) First college generation 0.081 (0.128) Major type: Economics 0.867 (0.378)

Major type: Marketing 0.588 (0.270) Major type: Finance 0.315 (0.321) Major type: Accounting 0.426 (0.261) Major type: Management 0.247 (0.265) Ethnicity: White ¡0.659 (0.445)

Ethnicity: Hispanic ¡0.462 (0.449)

Ethnicity: Black ¡0.853 (0.519)

Ethnicity: Asian ¡0.432 (0.539)

Model characteristics

R2 .704

AdjustedR2 .452

N 242

Note.Unstandardized parameters are shown. Standard errors are in parenthe-ses. NSDnot supported; SDsupported.

yp

<.10.p<.05.p<.01.

outcome that is relevant to them (expectancy), if they perform as expected that a greater reward may be achieved (instrumentality), and that the actual outcome is attractive to them (valence).

Age was a negative indicator of intention to participate in a PSO. It is very likely that many older students have additional responsibilities such as a spouse, children, or a job that takes precedence for them. It might also be more important as they grow older and as their graduation date approaches to start focusing on searching for employment rather than remaining involved in PSOs. These results imply that advisors should actively promote enrollment into PSOs when students are younger to be able to offer a worthy experience. Recruitment then needs to start in the freshman and sophomore years. To attract older students, a different range of benefits would have to be promoted and included such as help with resumes, interviewing skills, or guidance in job searching. Offering these benefits could be coordinated with a career development office to avoid creating responsibilities for the faculty member and thus effectively use everyone’s time and resources.

Regarding the control variables, the analysis showed that being a member augments intentions to participate in such organizations. This increase in intentions is somehow expected as members who have already joined an organiza-tion probably already understand the value of member-ship, just as the previously discussed expectancy theory suggests. Along these lines, the results showed that ethnic-ity and being afirst generation college student do not infl u-ence a student’s intention to participate. Perhaps in a crowded marketplace of student organizations, the mes-sage needs to highlight what students truly value, which this study found were contact with professionals and pro-fessional development among a young student base, instead of what we as faculty advisors think they want.

Overall, the research findings provide valuable insights for the elaboration of strategies that assist with member participation and likely with recruitment and retention in PSOs; however, a qualitative approach could

also yield rich results. Qualitative inquiry through focus groups and in-depth interviews could magnify our understanding of students’ motivations pertaining to participation and membership. Future researchers then could explore specific strategies that contribute to under-standing student motivations with respect to member-ship and continued growth of PSOs. In addition, future studies may benefit from an understanding of what drives such motivation to participate by using theories such as expectancy theory, goal theory, and equity the-ory. For example, based on expectancy theory, future work could examine what drives the expectancies, instru-mentalities, and valences that make up the motivational force among a student base. What are the interactions of such motivational force on additional aspects of the stu-dent’s life?

One limitation of this study was the presence of some multicollinearity among the experiential learning activi-ties. To some extent it would be expected that they were highly correlated as they all represent a very similar set of activities. The scale structures were confirmed via CFA as previously mentioned, but a high correlation among them persisted. Thus, a further study where the activities are re-evaluated is warranted.

This study provided an initial exploration into the drivers of intention for students to participate in a PSO. There are many more drivers of intention that could be investigated as this study reviewedfive experiential activi-ties. In addition, investigating moderating variables could yield insight into how to attract and retain students. By continuing to understand what motivates intention to join PSOs, advisors and colleges would be better posi-tioned to offer value that is relevant to the student.

References

American Marketing Association. (2013). Faculty advisor

resources. Retrieved from http://www.marketingpower.

com/Community/collegiate/Pages/AdvisorResources.aspx Table 5.Application of significantfindings for student organizations advisors.

Experiential learning activities Application

Contact with professionals Schedule activities that include: business speakers, hiring managers, and alumni. Involvement with several industries and the community based on student’s interests could be explored. Training and coaching opportunities could be developed with local as well as national companies with a local presence. Alumni and attendance to local professional events area valuable resource for networking.

Professional development Events aimed at career advancements and personal growth should be pursued. Examples include: developing teamwork and organizational skills, improving self-confidence, leadership training, practicing business skills, and negotiation workshops. Participation in local, regional, or national events such as case competitions and business projects or charity-based tasks are also great options.

Entrepreneurial activities Although activities such as: new product development, how to start or run a small business, and how to identify markets for small businesses were a negative predictor we do not recommend that they are excluded from the organizations’activities. We encourage advisors to assess whether the current members are risk averse to entrepreneurship and then adapt accordingly. In this way, these activities bring value to that type of student who is not averse to the idea of launching their own business.

50 L. MUNOZ ET AL.

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2013).Curriculum development series. Retrieved from http://www.aacsb.edu/seminars/curriculum-develop ment-series/experiential-learning/

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models.Journal of the Academy of Marketing Sci-ence, 16,74–94.

Barber, J. P. (2012). Integration of learning: A grounded theory analysis of college students’learning.American Educational Research Journal, 49,590–617.

Bobbitt, L. M., Inks, S. A., Kemp, K. J., & Mayo, D. T. (2000). Integrating marketing courses to enhance team-based expe-riential learning.Journal of Marketing Education, 22,15–24. Borzak, L. (1981). Field study: A sourcebook for experiential

learning. Beverley Hills, CA: Sage.

Bruner, J. S. (1960).The process of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Buchner, T. W. (2007). PM Theory: A look from the perform-er’s perspective with implications for HRD. Human

Resource Development International, 10,59–73.

Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.),

Modern methods for business research(pp. 295–336).

Mah-wah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Chin, W. W., Marcolin, B. L., & Newsted, P. R. (2003). A par-tial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study.Information Systems Research, 14,189–217.

Clark, W. R., & Kemp, K. J. (2008). Using the six principles of influence to increase student involvement in professional organizations: A relationship marketing approach.Journal

for Advancement of Marketing Education, 12,43–51.

DeNisi, A. S., & Pritchard, R. D. (2006). Performance appraisal, PM, and improving individual performance: A motivational framework. Management and Organizational Review, 2, 253–277.

DeSanctis, G. (1983). Expectancy theory as explanation of vol-untary use of a decision support system. Psychological Reports, 52,247–260.

Dewey, J. (1938).Logic: The theory of inquiry. New York, NY: Holt.

Forman, H. (2006). Participative case studies: Integrating case writing and a traditional case study approach in a market-ing context.Journal of Marketing Education, 28,106–113. Hair, J. F., Tatham, R. L., Anderson, R. E., & Black, W. (1998).

Multivariate data analysis(5th ed.). New York, NY:

Pren-tice-Hall.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria forfit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria ver-sus new alternatives.Structural Equation Modeling: A Mul-tidisciplinary Journal, 6,1–55.

Hunt, S. D., & Madhavaram, S. (2006). Teaching marketing strategy: Using resource-advantage theory as an integrative

theoretical foundation.Journal of Marketing Education, 28, 93–105.

Kidwell, B., & Jewell, R. D. (2003). An examination of per-ceived behavioral control: Internal and external influences on intention.Psychology & Marketing, 20,625–642. Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the

source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall.

Kolb, D. A., Boyatzis, R. E., & Mainemelis, C. (2001). Experien-tial learning theory: Previous research and new directions. In R. J. Sternberg & L.-F. Zhang (Eds.), Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles(pp. 227–247). Mah-wah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kutner, M. H., Nachtsheim, C., Neter, J., & Li, W. (2004).

Applied linear regression models (5th ed.). New York, NY:

McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

McCarthy, P. R., & McCarthy, H. M. (2006). When case studies are not enough: Integrating experiential learning into business curricula.Journal of Education for Business, 81,201–204. Osland, J. S., Kolb, D. A., Rubin, I., & Turner, M. E. (2007).

Organizational behavior: An experiential approach (8th

ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Peltier, J. W., Scovotti, C., & Pointer, L. (2008). The role the collegiate American Marketing Association plays in profes-sional and entrepreneurial skill development. Journal of

Marketing Education, 30,47–56.

Petkus, E. Jr. (2000). A theoretical and practical framework for service-learning in marketing: Kolb’s experiential learning cycle.Journal of Marketing Education, 22,64–70.

Saunders, P. M. (1997). Experiential learning, cases, and simu-lations in business communication. Business Communica-tion Quarterly, 60,97–114.

Scott, A. (2013). What do employers really want from college

grads? Retrieved from http://www.marketplace.org/topics/

economy/education/what-do-employers-really-want-col lege-grads

Serviere-Munoz, L. (2010). Epigrammatic sales scenarios and evaluations: Incorporating the experiential learning approach to research, development, and grading of sales presentations.Journal for Advancement of Marketing Edu-cation, 17,112–117.

Serviere-Munoz, L., & Counts, R. W. (2014). Recruiting millen-nials into student organizations: Exploring Cialdini’s princi-ples of human influence.Journal of Business and Economics, 5,306–315.

Serviere-Munoz, L., & Poole, S. M. (2014).Motivating partici-pation in student organizations: Assessing the role of

experi-ential learning activities and Cialdini’s principles of

influence. Paper presented at the Marketing Educator’s

Association Conference, San Fransisco, CA.

Vowels, S. A. (2005). Using blackboard to sustain student organizations.National On-Campus Report, 33(21), 3. Vroom, V. H. (1965).Work and motivation. New York, NY:

Wiley.