Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Challenge Is Key: An Investigation of Affective

Organizational Commitment in Undergraduate

Interns

Marlene A. Dixon , George B. Cunningham , Michael Sagas , Brian A. Turner &

Aubrey Kent

To cite this article: Marlene A. Dixon , George B. Cunningham , Michael Sagas , Brian A. Turner & Aubrey Kent (2005) Challenge Is Key: An Investigation of Affective Organizational Commitment in Undergraduate Interns, Journal of Education for Business, 80:3, 172-180, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.80.3.172-180

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.80.3.172-180

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 174

View related articles

he relationship between affective organizational commitment and positive work outcomes has been well established in a number of industries (Angle & Lawson, 1994; Becker, Billings, Eveleth, & Gilbert, 1996; Meyer & Allen, 1991; Meyer, Paunonen, Gellatly, Goffin, & Jackson, 1989; Mow-day, 1998; Somers & Birnbaum, 1998; Vandenberghe, Bentein, & Stinglhamber, 2004). For example, Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, and Topolnytsky (2002) demonstrated that affective commitment, or the employees’ desire to stay with the organization because he or she wants to, has been linked consistently to increased job performance, increased organization-al citizenship behaviors (OCBs), increased attendance, decreased turnover intentions, and decreased turnover behavior (see also Meyer & Allen, 1991; Meyer et al., 1989). Vandenberghe et al. found that supervisor commitment and organizational commitment were related to employee performance and intent to quit. Somers and Birnbaum found that organizational commitment was not related to “task efficiency” types of per-formance but was strongly related to other beneficial outcomes such as client satisfaction. Angle and Lawson found that affective commitment was related to

supervisor ratings of dependability and initiative. These authors argued that increased affective commitment to the organization produces individual proso-cial behaviors (or OCBs), which eventu-ally benefit the entire organization (Organ, 1988). Although these benefits may not always be noticed with a very narrow, task-type performance-depen-dent variable, they are certainly apparent when one considers the whole of organi-zational effectiveness.

Although organizational commitment has been investigated in the context of established employees, we found little research on the commitment of interns. The intern experience, although short term in nature, may represent a critical

time for forming impressions of an organization. Meyer and Allen (1988) argued, “The early months of employ-ment have been identified as a particu-larly important period in the develop-ment of work attitudes” (p. 197). These authors suggested that many new employees are disappointed when they perceive that their jobs lack challenge, opportunity for growth, and support. As a consequence, new employees may fail to develop an attachment to an organi-zation and leave prematurely. Converse-ly, in a positive atmosphere, employees can develop significant attachments in as little as 6 months (a timeframe simi-lar to that of most internships, which typically last 4 to 12 months). Specifi-cally, Meyer and Allen found that employees whose pre-entry expecta-tions were confirmed, who had chal-lenging jobs, and who had a sense of independence felt more affectively com-mitted to their respective organizations, even within the first 6 months of their employment.

If the early months of actual employ-ment are critical, surely the internship also represents an important time for developing attachments (or a lack of attachment) to an organization and per-haps even a career (Cunningham, Sagas,

Challenge Is Key:

An Investigation of

Affective Organizational Commitment

in Undergraduate Interns

MARLENE A. DIXON BRIAN A. TURNER

The University of Texas at Austin The Ohio State University ` Austin, Texas Columbus, Ohio

GEORGE B. CUNNINGHAM AUBREY KENT

MICHAEL SAGAS Florida State University

Texas A&M University Tallahassee, Florida College Station, Texas

T

ABSTRACT. In this study, the authors investigated factors related to affective organizational commitment in undergraduate interns. They exam-ined job challenge, supervisor sup-port, and role stress as antecedents to commitment. Results based on a sam-ple of senior undergraduate students (N= 71) showed that the 3 work vari-ables explained 35% of the variance in affective organizational commitment. The authors discuss implications for educators and managers in charge of designing and implementing quality internships.

Dixon, Kent, & Turner, in press; Gault, Redington, & Schlager, 2000; Lee, Car-swell, & Allen, 2000). Thus, improving the work experiences of interns may serve to increase not only their affective commitment to the organization but also their long-term commitment to the occupation.

In this study, we sought to investigate factors related to affective organization-al commitment in interns. Specificorganization-ally, we examined job challenge, supervisor support, and role stress as potential antecedents to commitment. From a the-oretical standpoint, our results expand the boundaries of organizational com-mitment literature, which previously has focused almost exclusively on paid employees. From a practical standpoint, the results provide suggestions for edu-cators and managers, especially as they work together on designing effective internships that benefit both the intern and the organization.

Conceptual Background

Although the employee and employ-er both know that the intemploy-ern relation-ship is not a guarantee of future employment, developing intern com-mitment is important for both parties because many organizations eventually hire their interns (Gault et al., 2000). Thus, we provide a review of the im-portance of affective organizational commitment to both the organization and the intern. Then, we present an overview of previous approaches to commitment in general, review the the-oretical and empirical antecedents of affective commitment, and present spe-cific research hypotheses.

Importance of Intern Affective Organizational Commitment

For the organization, interns provide a valuable source of future employees with qualified experience (Gault et al., 2000). In 1994, researchers estimated that over 25% of new hires had intern-ship experience and that that number was growing (Gault et al.; Watson, 1995). This employee pool represents an already trained workforce that can make an immediate contribution to an organization. It also represents a

consis-tent labor pool in times of economic downturn. Further, hiring from the intern pool saves the organization a sig-nificant amount of money both in hiring and training costs (Pianko, 1996). It is much less expensive to hire interns than to recruit and select candidates from an at-large pool. Watson estimated these savings to be $15,000 per hire. In terms of training, organizations clearly would want to avoid the sunk costs of training interns who simply turn over to other organizations at the end of their intern-ship period (Pianko). Organizations have a vested interest in retaining the interns that they train.

Because interns represent a source of labor, intern affective commitment is important not only to the future of orga-nizations but also to the current opera-tions. Affective organizational commit-ment consistently has been linked to positive employee behaviors such as OCBs and helping behaviors (Meyer & Allen, 1991; Meyer et al., 1989; Meyer et al., 2002). Although the link between OCBs at an individual level and organi-zational effectiveness at the firm level has been relatively weak, the link at the group level is much stronger (Ostroff, 1992). In a group setting, human resource management practices can “fos-ter salient productivity-related behav-iors” such as performance, citizenship, and attachment (Ostroff & Bowen, 2000, p. 227). The practices work to establish shared meanings among group members regarding valued attitudes and behaviors. One individual act of citizenship behav-ior, therefore, may demonstrate a very weak relationship to overall organiza-tional performance. However, a collec-tive atmosphere focused on helping behaviors and collaborative effort may lead to multiple acts of citizenship that have a substantial impact on organiza-tional performance. Thus, within a given group of interns, management could cre-ate a “commitment atmosphere” in which “individuals’ attitudes and behav-iors combine to emerge into a collective effort that is greater than the simple addi-tive effect across individuals” (Ostroff & Bowen, p. 229). OCBs and extra-role behavior of interns, even in a short-peri-od assignment, can make a significant contribution to the effectiveness of orga-nizations, especially those that train a

“class” of interns simultaneously or that rely heavily on interns to supplement their full-time staff (Gault et al., 2000).

Consider an example of a ticket sales department for a professional sport fran-chise that is comprised of interns and full-time employees. A group of affec-tively committed interns who really want to see the organization do well easily could outsell the full-time employees regardless of the fact that they are only on short-term assignment and have no guarantee of future employment. Employees need not be employed full time or long term to con-tribute to organizational effectiveness.

Creating this commitment atmosphere may be even more important for interns, as many of them are unpaid (Gault et al., 2000). With employees, organizations may be able to enhance firm perfor-mance with bonuses and perforperfor-mance incentives. Indeed, performance-based compensation has been linked to firm performance in several industries (Banker, Lee, Potter, & Srinivasan, 1996; Gerhart & Milkovich, 1990). With interns, however, these types of human resource management practices are like-ly not available; hence, management must find other ways to foster commit-ment and enhance firm performance.

Affective commitment also benefits the interns. These benefits are derived not only from the commitment itself, but also from the enhanced work environ-ment that leads to commitenviron-ment (Meyer & Allen, 1988). For example, interns benefit from challenging jobs that improve their work skills and help define their skill set (Gault et al., 2000), regardless of the link to affective organi-zational commitment. In addition, affec-tively committed interns may benefit from a sense of importance and belong-ing that comes from attachment to an organization (Gault et al.; Meyer & Allen; Meyer, Allen, & Gellatly, 1990). Affectively committed interns also have leverage when full-time employment offers are presented because they are likely to be sought after by multiple organizations (Gault et al.), including the one for which they are currently working.

Given the large potential labor pool that interns provide, the benefits of commitment for both parties, and the

fact that the majority of internships are unpaid, differences in affective organi-zational commitment potentially could have a large impact on organizational strategy, cost-cutting measures, and effectiveness, even within the short time frame of their assignments. Highly committed interns are likely to devote more time and creative energy to their organization and to choose to stay with that organization once their internship is completed.

Three-Component Model of Commitment

Allen and Meyer (1990) proposed that commitment is a multidimensional construct composed of three distinct yet related types of commitment. Accord-ing to their model, affective commit-mentrefers to an emotional attachment to an organization and identification with that organization such that the per-son remains with the organization because he or she wants to. Continu-ance commitment refers to the per-ceived costs associated with leaving an organization. In other words, a person with continuance commitment stays with an organization because he or she

has to, owing to the costs and opportu-nities of leaving. A third type of com-mitment is normative commitment, which reflects a person’s desire to stay with an organization because he or she feels obligated; the individual feels that he or she ought tostay.

Meyer et al. (2002) tested this three-component model through meta-analysis. Their purpose was to investigate the rela-tionship between the three components along with the antecedents and conse-quences of all three types of commit-ment. In response to the number of schol-ars that have questioned normative commitment as a unique component of organizational commitment (Angle & Lawson, 1994), the meta-analytic results demonstrated that affective and norma-tive constructs are not identical and that normative commitment is rather poorly understood. Meyer et al. suggested that the combined research has left us with many questions regarding what norma-tive commitment is, how it develops, and how it influences behavior.

Meyer et al. (2002) also found that

continuance commitment was different from the other two constructs and relat-ed to work outcomes in the opposite direction. However, continuance com-mitment continues to generate argument regarding whether it is one construct or two. The researchers found that two subcomponents—high sacrifice and low alternatives—were related differently to turnover intentions. Because of these construct and measurement issues regarding continuance and normative commitment, and because of the consis-tently strong relationship between affec-tive commitment and posiaffec-tive work out-comes, in this study the only dimension that we used from the Allen and Meyer (1990) study was affective commitment.

Antecedents of Affective Commitment

A number of work-related variables have been shown to be antecedents of affective commitment in full-time employees, particularly at early stages of their employment (i.e., 1st year) (Meyer & Allen, 1988). Meyer and colleagues argued, “ . . . attempts to recruit or select employees who might be predisposed to being affectively committed will be less effective than will carefully managing their experience following entry” (2002, p. 38). The premise behind the stronger relationship of work experiences is that they can be somewhat controlled by the organization through human resource management, job design, and leadership that enhance the employees’ commit-ment. This improved management is purported to benefit both the organiza-tion and the employee (Meyer & Allen).

One general theory describing the mechanism of enhancing commitment through work experiences is Farrell and Rusbult’s (1981) reward/cost paradigm. According to Farrell and Rusbult, indi-viduals place job properties into two categories—rewards and costs— according to how much they value those properties and/or actually experi-ence them. Rewards include such job properties as challenge, autonomy, supervisor support, coworker support, and organizational justice. Costs include job hazards, stress, and rou-tinization (Iverson & Buttigieg, 1999; Mathieu & Zajac, 1990). According to this argument, as rewards increase and

costs decrease, commitment increases. For example, an intern in a challenging job with low routinization and high supervisor support would be more com-mitted to an organization than would an intern with a very routine job and little supervisor support.

This reward/cost paradigm is consis-tent with traditional theory that explains organizational commitment as a four-step process (Buchanan, 1974; Meyer & Allen, 1988; Steers, 1977). First, the organization meets employee needs. Second, because those needs are met, employees perceive a favorable ex-change relationship with the organiza-tion. Third, the employees become favorably disposed toward the organiza-tion. Fourth, the employees, therefore, become more committed to that organi-zation (Buchanan; Meyer & Allen; Steers; Vandenberghe et al., 2004). Iver-son and Buttigieg (1999), Meyer and Allen, Meyer et al. (2002), and Vanden-berghe et al. all have found support for this exchange-relationship explanation of affective commitment in full-time employees.

Although the reward/cost and exchange paradigms provide a general framework in which to view the rela-tionship between work characteristics and affective commitment, specific work characteristics may require further explanation. That is, how do particular work characteristics come to be charac-terized as rewards or costs? How do these characteristics meet employee needs in such a way that the employees perceive a favorable exchange relation-ship with the organization? Job chal-lenge, supervisor support, and role stress are work experience attributes that have held consistently strong rela-tionships with affective commitment in full-time employees (Iverson & Buttigieg, 1999; Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Meyer & Allen, 1988; Meyer et al., 2002). We will explore each of these characteristics in greater detail.

Job challenge. Job challengeis defined as the excitement and stimulation asso-ciated with a particular task set (Meyer & Allen, 1988). For interns, challenging jobs are ones that may require new skills or that give individuals the oppor-tunity to work with at least some level

offers rewards and meets their personal needs of accomplishment and belong-ing, their affective organizational com-mitment likely would increase also (Farrell & Rusbult, 1981; Iverson & Buttigieg, 1999; Meyer et al., 2002).

This reasoning led us to our second hypothesis:

H2: Supervisor support will be positively associated with affective organizational commitment in interns.

Role Stress. According to Iverson and colleagues (1998), role stress is a com-bination of role conflict and role ambi-guity. It results from employees’ need to reconcile conflicting task requirements (role conflict) and from their not having sufficient information to complete job requirements (role ambiguity). Meyer and Allen (1997) argued that affective commitment was likely to be low among employees who “are unsure about what is expected of them (role ambiguity) or who are expected to behave in ways that seem incompatible (role conflict)” (p. 45). Mathieu and Zajac (1990) also found that role con-flict and role ambiguity were negatively related to commitment. They argued that little theoretical work has been devoted to explaining why this relation-ship exists. The common assumption,

By showing interest in an employee and

communicating the organization’s valuing of him

or her, a supervisor can help build the employee’s

commitment to that organization.

communicating the organization’s valu-ing of him or her, a supervisor can help build the employee’s commitment to that organization. For example, supervi-sors who provide constructive feedback to employees—especially if they give the employee the opportunity to have a voice in that feedback—may enhance perceptions of trust in the organization. Greater trust leads to satisfaction and commitment (Cropanzano & Green-berg, 1997; GreenGreen-berg, 1982; Kluger & DeNisi, 1996; Walker & Smither, 1999).

Supervisor support also has been found to reduce role strain, depersonal-ization, and emotional exhaustion. Both Ray and Miller (1991) and Iverson et al. (1998) found that supervisor support decreased emotional exhaustion, which in turn increased job satisfaction. Fur-ther, Iverson et al. found that supervisor support was related negatively to deper-sonalization and related positively to personal accomplishment. That is, when employees did not sense support from their supervisor, they were emotionally exhausted and disconnected from the organization. On the other hand, when they perceived support from their super-visor, they also felt more connected to the organization (and the organization’s clients) and accomplished more worth-while activities on the job (Iverson et al.). Supervisor support, therefore, can

turn costs (depersonalization, emotional exhaustion) into rewards (personal accomplishment). Rewards, as we have noted, lead to a favorable view of the organization and therefore to organiza-tional commitment. Although Iverson et al. investigated depersonalization and personal accomplishment as they relate to job satisfaction, it is not a large jump to contend that similar relationships exist with regard to organizational com-mitment. That is, as employees increas-ingly perceive that the organization of independence (Meyer & Allen).

Challenging jobs represent an opportu-nity to learn new skills and apply theo-retical concepts to the work world (Cuneen & Sidwell, 1994). A number of studies have suggested that job chal-lenge is positively related to affective organizational commitment through the mechanisms of empowerment and indi-vidual development (Arthur, 1994; Birdi, Allan, & Warr, 1997; MacDuffie, 1995; Moreland & Levine, 2001; Mow-day, 1998). Arthur suggested that prac-tices that increase job challenge and variety can empower individuals to reach their personal goals. Employees who become empowered through job challenge perceive that the organization is committed to helping them meet their individual needs. They are, therefore, more likely to view the organization favorably and to become more commit-ted to it (Buchanan, 1974; Meyer & Allen; Steers, 1977).

Challenging positions also often require that the employee receive fur-ther training and development. Although training and development serve to enhance employee knowledge and skills, they also serve a latent func-tion of communicating to employees (especially new ones) that they are valu-able to the organization (Moreland & Levine, 2001). In fact, participation in required training and development pro-grams has been empirically linked to higher job satisfaction and organization-al commitment (Birdi et organization-al. 1997). Employees view their being valued by the organization as a reward, which leads them to demonstrate greater com-mitment to the organization.

Thus, we formulated our first hypothesis:

H1: Job challenge will be associated positively with affective organizational commitment in interns.

Supervisor support. This work experi-ence attribute is defined as the degree of consideration, information, and task assistance provided by an individual’s supervisor (Iverson, Olekalns, & Erwin, 1998). Support works as both an increased reward and a decreased

cost. It represents an increased reward through the mechanism of trust (Cropanzano & Greenberg, 1997). It is also a decreased cost because it limits the role of strains or stressors (Iverson et al.).

Trust operates on two levels. Like training and development, supervisor support can represent a commitment to the employee by the organization (Arthur, 1994; Mowday, 1998). By showing interest in an employee and

however, has been that perceptions of the work environment lead to affective responses such as satisfaction and com-mitment (Mathieu & Zajac). That is, when an individual perceives the work environment to be unfavorable, he or she is likely to react not with behavioral responses such as turnover or absen-teeism, but with affective responses such as reduced satisfaction and decreased commitment.

This argument is consistent with the reward/cost and exchange paradigms. Frustration with a work environment— one entailing role conflict or ambigui-ty—is considered a cost to the employee. Frustration does not lead to meeting one’s needs nor to a favorable exchange. Thus, the employee who experiences high levels of role stress likely would have lower commitment than one who does not.

Thus, we formulated our third hypothesis:

H3: Role stress will be associated negatively with affective organizational commitment in interns.

Method

Participants

The participants in our study were final-semester senior undergraduate stu-dents (N= 71) from a convenience sam-ple of four universities from various geo-graphic regions in the United States. The students were completing their intern-ships primarily in the sports and recre-ation industry (e.g., professional sports teams, community recreation facilities, collegiate athletic organizations). The interns performed a wide variety of tasks for their sponsoring organizations: ad-ministrative duties, ticket sales, game-day operations, computer technical sup-port and programming, and so forth. All persons voluntarily consented to partici-pate in the study, which consisted of an in-person questionnaire distributed at the completion of their internships. This ability to have the interns complete the questionnaire in person resulted in a response rate of 100%. The sample of interns was 53.5% female, 91.5% Cau-casian, and 54.9% unpaid. Participants

had a mean age of 22.59 years (SD = 1.54) and had an average of 1.24 years (SD= 1.65) of previous experience in the sports industry.

Measures

Participants completed a question-naire that asked them to provide basic demographic information (provided above) and to respond to items related to their affective organizational commit-ment, job challenge, role stress, and supervisor support. To measure all items, we used a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

The in-person survey instrument was derived from established valid scales. To further ensure validity and reliability, we subjected the instrument to validity and reliability analyses. Thus, all relia-bility estimates reported in the follow-ing paragraphs were derived from the data in the current study. In addition, we established face validity by having a panel of experts in human resource management and organizational com-mitment review the instrument. We made changes to clarify instructions or wording according to the experts’ com-ments. Then, we had the instrument tested by a group of underclass sports management students who were not currently enrolled in an internship field.

Affective organizational commitment. For measuring affective organizational commitment, we had participants use three items from Meyer and Allen’s (1991) scale. Previous research has demonstrated the efficacy of using a 3-item measure (Clugston, Howell, & Dorfman, 2000; Iverson & Buttigieg, 1999). The following sentence is a sam-ple item: “The organization in which I am interning has a great deal of person-al meaning to me.” The reliability esti-mate for the 3-item scale was .77.

Supervisor support. Supervisor support was measured through three items adapt-ed from Iverson et al. (1998) and Green-haus, Parasuraman, and Wormley (1990). A sample item is “My manager is very concerned about the welfare of those under him/her.” The reliability estimate for the measure was high (α= .93).

Job challenge. To measure job chal-lenge, we used three items adapted from Meyer and Allen’s (1988) scale. A sam-ple item is “In general, the work I per-form in this internship is challenging and exciting.” The reliability estimate for this scale was high (α= .84).

Role stress. We used six items from Iver-son et al. (1998) to measure role stress. A sample item is “I get conflicting results from two or more people at my internship site.” The measure demonstrated a high internal consistency (α= .84).

Control Variables

A number of demographic variables— including age, gender, and education— have been shown to contribute at least minimally to affective commitment (Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Meyer et al., 2002). In this study, we controlled for age and education in the sample selec-tion, as the interns were homologous with respect to these variables. However, participants did differ according to gen-der; thus, we used this variable as a con-trol in the statistical analyses.

Because previous experience in the field could influence the expectations that people have, as well as the particular positions that they are assigned, we also controlled for previous experience in the sports industry. Finally, research has demonstrated a positive relationship between compensation and organization-al commitment (Gerhart & Milkovich, 1990; Greenberg, 1982). Therefore, internship compensation served as the final control variable.

Data Analysis

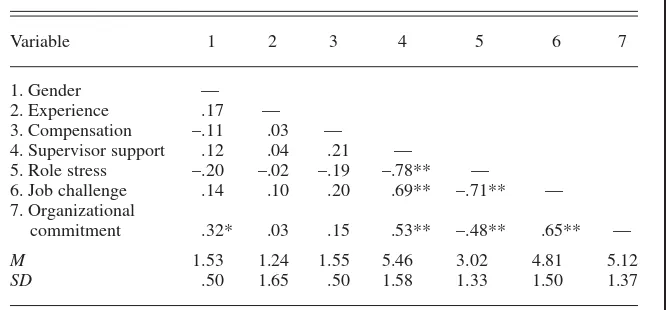

We calculated means, standard devi-ations, and bivariate correlations for all variables. The hypotheses predicted that the three work attributes would all hold significant associations with affec-tive organizational commitment. We tested our hypotheses through hierar-chical regression analysis, with the con-trols (gender, experience, and compen-sation) entered in the first step, the three work experiences entered in the second step, and affective organization-al commitment serving as the depen-dent variable.

Results

We present our descriptive statistics in Table 1. Examination of the mean scores reveals high scores for supervisor sup-port, job challenge, and affective organi-zational commitment. One-sample t

tests indicated that the mean scores for the aforementioned variables all were significantly greater than the midpoint of the scale (4; all ts ≥ 4.60, p < .001). Additionally, the mean score for role stress was low, and significantly lower than the midpoint of the scale (4; t = –6.21,p< .001). Finally, in general sup-port of the hypotheses, an examination of the bivariate correlations indicated that affective organizational commit-ment was positively related to both supervisor support and job challenge and negatively related to role stress.

Hypotheses 1 through 3 predicted that

job challenge, supervisor support, and role stress would hold significant associ-ations with affective organizational com-mitment. In Table 2, we present the results of the regression analysis that we used to test these predictions. Variance inflation factor values were less than Hair, Anderson, Tatham, and Black’s (1998) recommended cutoff of 10, indi-cating that multicollinearity was not a problem.

The first step accounted for 14% (p< .05) of the variance in affective organi-zational commitment. After controlling for these effects, the three work experi-ences accounted for 36% unique vari-ance (p< .001; adjusted R2= .35). We

examined the data further and found that job challenge was the only significant predictor of affective organizational commitment (β = .58,p< .001). Thus, although all the work experiences held

significant bivariate correlations with affective organizational commitment, when considered together, only job chal-lenge was a significant predictor of the dependent variable. Therefore, sis 1 was supported, whereas Hypothe-ses 2 and 3 were not.

Discussion

Although affective organizational commitment has been investigated in full-time employees, very little attention has been given to interns, who are an important source of employees for many organizations. Our aim in this study was to examine the antecedents of affective organizational commitment in interns and to make practical applica-tion of these findings to internship design and implementation.

From a descriptive standpoint, the commitment level of interns was rather high. The control variables explained 14% of the variance on affective organi-zational commitment, whereas work variables explained 36%. Overall, there-fore, the model explained half of the variance in affective organizational commitment for the sample.

It is also notable that the women in the current study had greater commitment than the men. This finding is in contrast to previous meta-analytic findings indi-cating that men demonstrated greater commitment than women (Meyer et al., 2002) or that the gender–commitment relationship was inconclusive (Mathieu & Zajac, 1990). This finding may be specific to the sports industry. That is, the sports industry is traditionally male dominated (Coakley, 2004). For exam-ple, according to Acosta and Carpenter (2002), men held over 60% of all admin-istrative positions, and 87.7% of sports information positions in the NCAA institutions. As women seek to enter sports organizations, they may find that they have to be more committed than their male counterparts to “survive” in the industry. Alternatively, knowing the obstacles that they would face within that industry, women who are not com-mitted likely would self-select out of a major such as sports management before they reach the internship stage, leaving only the highly committed individuals to complete the internship process.

TABLE 2. Results of Hierarchical Regression Testing the Effects of Job Challenge, Supervisor Support, and Role Stress on Organizational Com-mitment

Variable B SE β R2 ∆R2

Step 1 .14 .14*

Gender .94 .32 .35**

Experience –.02 .10 –.03 Compensation .51 .31 .19

Step 2 .50 .36***

Job challenge .53 .12 .58*** Supervisor support .19 .13 .22 Role stress .17 .16 .17

*p< .05. **p< .01. ***p< .001.

TABLE 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Bivariate Correlations

Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

1. Gender —

2. Experience .17 — 3. Compensation –.11 .03 —

4. Supervisor support .12 .04 .21 —

5. Role stress –.20 –.02 –.19 –.78** —

6. Job challenge .14 .10 .20 .69** –.71** — 7. Organizational

commitment .32* .03 .15 .53** –.48** .65** —

M 1.53 1.24 1.55 5.46 3.02 4.81 5.12 SD .50 1.65 .50 1.58 1.33 1.50 1.37

Notes. Gender: 1 = male, 2 = female; compensation: 1 = compensated, 2 = not compensated. *p< .01. **p< .001.

Based on previous literature on full-time employees, Hypotheses 1 and 2 predicted that job challenge and super-visor support would be positively relat-ed to affective organizational commit-ment, and Hypothesis 3 maintained that role stress would be negatively related to affective organizational commitment. Indeed, the three work variables com-bined to explain 35% of the variance in affective organizational commitment, a finding that is consistent with previous literature regarding the importance of work characteristics over job character-istics in the examination of affective organizational commitment (Meyer & Allen, 1988; Meyer et al., 2002).

Individually, job challenge held a sig-nificant, positive, and rather strong asso-ciation with affective organizational commitment, whereas supervisor sup-port and role stress were not significant-ly related. In the intern sample, therefore, job challenge was apparently the most important work characteristic related to affective organizational commitment.

This finding is consistent with previ-ous literature suggesting that although some internships are valuable for all students for gaining experience and exploring potential career options, cer-tain types of internships are more valu-able than others, especially those that provide students with the opportunity for self-concept crystallization and vocational self-efficacy (Brooks, Cor-nelius, Greenfield, & Joseph, 1995). These authors suggested that intern-ships consisting mostly of clerical work, for example, would not help students realize whether or not they liked the field (or organization) or whether or not they were going to be successful in that field. Conversely, students given chal-lenging tasks and a variety of tasks would be able to determine better not only their desire to enter the career (or organization) but also their work or career efficacy.

The relationship between supervisor support and affective organizational commitment and that between role stress and affective organizational com-mitment were not supported. One potential explanation for this finding is that interns are likely to work for a num-ber of supervisors, because of either a rotation within the organization (i.e.,

job rotation that allows them to try out different types of tasks) or a lack of clear lines of responsibility (i.e., an intern may complete tasks for a number of supervisors within a single work day). In fact, one criticism of intern-ships is inconsistency in supervision and organization of tasks (Gault et al., 2000). In contrast to full-time employ-ees, interns face less clearly defined lines of authority and less contact with their supervisors. This explanation does not discount the importance of the role of the supervisor but simply suggests that perhaps organizations are not struc-turing the supervision of interns in a way that maximizes its impact on affec-tive commitment.

The results related to role stress, although more difficult to explain, appear consistent with the literature regarding early expectations of workers as they enter the workforce (Meyer & Allen, 1988). Wanous (1980) argued that new employees often enter the organization with naïve optimism about how challenging and rewarding their jobs will be, especially when they have been recruited extensively for the job or have high educational credentials. When that job is not challenging and they meet other obstacles such as role stress and a lack of supervisor support, their satisfaction and commitment lev-els begin to decline. However, with numerous students sharing information about their internships both with other students and with professors who will advise those students, it is easy to see how interns might have more realistic expectations than other full-time employees who enter organizations with either biased or no information about the organization (Gault et al., 2000; Iverson & Buttigieg, 1999). If interns enter their workplace with a more real-istic set of expectations—that is, if they expect to have low-level jobs or con-flicting or confusing roles—they may not be subject to the same disappointing outcomes as other employees. There-fore, one plausible explanation for the findings is that role stress may not be as great a factor in intern commitment compared with full-time employee commitment because interns come into the internship expecting conflict and ambiguity.

For interns, the importance of job challenge may overshadow the supervi-sor and/or the work environment as a whole. In other words, the rewards have a greater influence than the costs. This explanation is consistent with an emerg-ing literature that finds self-concept reinforcement (Meyer & Allen, 1988), personal accomplishment (Iverson et al., 1998), vocational self-efficacy (Brooks et al., 1995), and similar indi-vidual outcomes to be paramount to sat-isfaction and commitment, particularly in interns and young employees. Gault et al. (2000) found that the greatest rewards for interns (especially over their student counterparts who did not com-plete an internship) were invaluable real work experience and a better under-standing of their career desires. Perhaps beyond supervisor support and low role stress, challenging jobs communicate the most to interns that they are valued and that their needs are being met with-in the organization. Therefore, challeng-ing jobs elicit the most commitment from interns.

One limitation of our study is the use of interns within a particular industry segment—the sports industry. To the extent that this industry is unique, the results may not be generalizable to other industries. Another limitation is our use of self-reports on work experiences. This design may be problematic if it introduces time-lagged effects on per-ceptions (Meyer & Allen, 1988). That is, organizations could potentially rec-ognize commitment in the interns and treat them preferentially, thereby alter-ing the interns’ perception of the work environment. The use of objective mea-sures of the work environment, particu-larly job challenge and supervisory sup-port, would strengthen the results.

Implications and Directions for Future Study

Several practical implications emerge from the findings of this study. The first is that employers should provide chal-lenging jobs, as opposed to routine or administrative tasks. Challenging jobs communicate to the interns that they are capable and valuable, and therefore will make them more willing to commit to the organization.

go beyond clerical or administrative tasks, providing interns with new expe-riences that require them to learn new skills and stretch their previous learn-ing. By providing challenging jobs and the training to perform them successful-ly, work organizations are communicat-ing to their interns that they are capable and valuable. This message is a power-ful one, generating a favorable relation-ship between organization and intern that can translate into multiple benefits for both parties.

REFERENCES

Acosta, R. V., & Carpenter, L. J. (2002). Women in intercollegiate sport: A longitudinal study—Twenty-five year update, 1977–2002. Retrieved from: www.northreadingsoftball. com/25yearsinwomenssports.pdf

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measure-ment and antecedents of affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization.

Journal of Occupational Psychology,63, 1–18. Angle, H. L., & Lawson, M. B. (1994). Organiza-tional commitment and employees’ perfor-mance ratings: Both type of commitment and type of performance count. Psychological Reports, 75,1539–1551.

Arthur, J. B. (1994). Effects of human resource systems on manufacturing performance and turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 37(3), 670–687.

Banker, R. D., Lee, S., Potter, G., & Srinivasan, D. (1996). Contextual analysis of performance impact of outcome-based incentive compensa-tion. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 920–948.

Becker, B., Billings, R. S., Eveleth, D. M., & Gilbert, N. L. (1996). Foci and bases of employee commitment: Implications for job

First, future research should consider the negative

aspects of commitment, such as separation

anxiety or disappointment if the intern is not hired

by the organization.

ment may produce other work out-comes. Third, although in this study we investigated antecedents of ment, the effects of affective commit-ment are not clearly understood for interns. Future research should consider the role of affective commitment on out-comes such as intern performance, like-lihood of securing employment, organi-zational effectiveness, recommendation of the internship, and other factors. Finally, researchers should work at developing a more clear understanding of the relationship of supervisor support and role stress to affective commitment, particularly in interns.

Conclusion

Interns represent a readily available, easily converted, and specifically trained workforce that can be a critical source of labor in today’s economy. Committed interns, especially as a group, have the potential to make an immediate impact on organizational effectiveness. This study represents a valuable extension in the literature on the antecedents of affective organiza-tional commitment in that we used interns rather than full-time employees. Consistent with previous research find-ings, our results indicate that work char-acteristics are the most important factor in developing affective organizational

commitment. For interns, we found that job challenge, in particular, was most strongly related to commitment.

From a practical standpoint, our results support a growing body of liter-ature underscoring the positive benefits of well-designed internship programs for both organizations and interns. Edu-cators need to work closely with the supervising organizations to ensure that the internships are challenging and rewarding. The best internships seem to Challenging jobs may also require

additional training or development. This argument may hold especially for interns, as their internship may be their first real work experience in the field in which they are studying. In fact, a growing body of evidence suggests that interns complete an internship pri-marily for the purpose of gaining criti-cal “real life” work training (e.g., com-puter languages, specific software applications) that they cannot gain in the classroom (Gault et al., 2000). As previous literature indicates, individu-als who complete company sponsored training and development are more likely to feel committed to an organi-zation because they feel the organiza-tion is committed to them (Birdi et al., 1997; Moreland & Levine, 2001). Interns who perceive that the organiza-tion is willing to invest in their training may become more committed to that organization.

Organizations also may want to review the way that their supervisor-intern relationships are structured. The findings indicate that supervisor support is not significantly related to affective organizational commitment. This find-ing may indicate that the role of the supervisor is not important. However, a more likely explanation is that the struc-ture of the supervisory role—having multiple and potentially contradictory supervisors to report to and to take direction from—may detract from the salience of the supervisor’s role in affective commitment. Organizations may wish to make the chain of com-mand more clear and provide the intern with more consistent interaction with the supervisor (Gault et al., 2000) to enhance affective commitment.

Educators also need to work closely with the sponsoring organizations to ensure that jobs are both challenging and well supervised. They also should develop communication networks with students and organizations so that stu-dents develop realistic expectations before entering the internship. If educa-tors inform students about the multiple roles that they may encounter and pro-vide strategies for dealing with role stress, those students may encounter less role stress once they are in the internship.

Although this study provides some insight into the antecedents of affective organizational commitment in interns, several directions for future research are necessary for furthering our understand-ing. First, future research should con-sider the negative aspects of commit-ment, such as separation anxiety or disappointment if the intern is not hired by the organization. Second, future research should consider the other aspects of commitment (normative and continuance), as these types of

performance. Academy of Management Jour-nal, 39(2), 464–482.

Birdi, K., Allan, C., & Warr, P. (1997). Correlates and perceived outcomes of four types of employee development activity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(8), 845–857. Brooks, L., Cornelius, A., Greenfield, E., & Joseph,

R. (1995). The relation of career-related work or internship experiences to the career development of college seniors. Journal of Vocational Behav-ior, 46, 332–349.

Buchanan, B. (1974). Building organizational commitment: The socialization of managers in work organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 19, 533–546.

Clugston, M., Howell, J. P., & Dorfman, P. W. (2000). Does cultural socialization predict mul-tiple bases and foci of commitment? Journal of Management, 26,5–30.

Coakley, J. (2004). Sports in society: Issues and controversies (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Cropanzano, R., & Greenberg, J. (1997). Progress in organizational justice: Tunneling through the maze. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.),

International review of industrial and organiza-tional psychology (vol. 12, pp. 317–372). Lon-don: Wiley.

Cuneen, J., & Sidwell, M. J. (1994). Sport man-agement field experiences. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technologies.

Cunningham, G., Sagas, M., Dixon, M. A., Kent, A., & Turner, B. A. (in press). Anticipated career success, affective occupational com-mitment, and intentions to enter the sport management profession. Journal of Sport Management.

Farrell, D., & Rusbult, C. E. (1981). Exchange variables as predictors of job satisfaction, job commitment, and turnover: The impact of rewards, costs, alternatives, and investments.

Organizational Behavior and Human Perfor-mance, 27, 78–95.

Gault, J., Redington, J., & Schlager, T. (2000). Undergraduate business internships and career success: Are they related? Journal of Marketing Education, 22, 45–53.

Gerhart, B., & Milkovich, G. T. (1990). Organiza-tional differences in managerial compensation and financial performance. Academy of Man-agement Journal, 33, 663–691.

Greenberg, J. (1982). Approaching equity and avoiding inequity in groups and organizations. In J. Greenberg & R. L. Cohen (Eds.),Equity and justice in social behavior (pp. 389–426). New York: Academic Press.

Greenhaus, J. H., Parasuraman, S., & Wormley,

W. M. (1990). Effects of race on organizational experiences, job performance evaluations, and career outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 64–86.

Hair, J. F., Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis

(5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Iverson, R. D., & Buttigieg, D. M. (1999).

Affec-tive, normaAffec-tive, and continuance commitment: Can the “right kind” of commitment be man-aged Journal of Management Studies, 36,

307–333.

Iverson, R. D., Olekalns, M., & Erwin, P. J. (1998). Affectivity, organizational stressors, and absenteeism: A causal model of burnout and its consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 52, 1–33.

Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A his-torical review, a meta-analysis, and a prelimi-nary feedback intervention theory. Psychologi-cal Bulletin, 119,254–284.

Lee, K., Carswell, J. J., & Allen, N. J. (2000). A meta-analytic review of occupational commit-ment: Relations with person- and work-related variables. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 799–811.

MacDuffie, J. P. (1995). Human resource bundles and manufacturing performance: Organization-al logic and flexible production systems in the world auto industry. Industrial and Labor Rela-tions Review, 48(2), 197–221.

Mathieu, J. E., & Zajac, D. (1990). A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commit-ment. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 171–194. Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1988). Links between

work experiences and organizational commit-ment during the first year of employcommit-ment: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 61, 195–209.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991). A three com-ponent conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61–89.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and applica-tion. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Gellatly, I. R. (1990). Affective and continuance commitment to the organization: Evaluation of measures and analysis of concurrent and time-lagged rela-tions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 710–720.

Meyer, J. P., Paunonen, S. V., Gellatly, I. R., Gof-fin, R. D., & Jackson, D. N. (1989). Organiza-tional commitment and job performance: It’s

the nature of the commitment that counts. Jour-nal of Applied Psychology, 74, 152–156. Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., &

Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 20–52.

Moreland, R. L., & Levine, J. M. (2001). Social-ization in organSocial-izations and workgroups. In M. Turner (Ed.), Groups at work: Theory and research (pp. 69–112). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Mowday, R. T. (1998). Reflections on the study and relevance of organizational commitment.

Human Resource Management Review, 8,

387–401.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexing-ton, MA: Lexington Books.

Ostroff, C. (1992). The relationship between satis-faction, attitudes, and performance: An organi-zational level analysis. Journal of Applied Psy-chology, 77(6), 963–974.

Ostroff, C., & Bowen, D. E. (2000). Moving HR to a higher level: HR practices and organiza-tional effectiveness. In K. J. Klein & S. W. Kozlowski (Eds.),Multilevel theory, research and methods in organizations (pp. 211–266). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Pianko, D. (1996, December). Power internships.

Management Review, 85, 31–33.

Ray, E. B., & Miller, K. I. (1991). The influence of communication structure and social support on job stress and burnout. Management Com-munication Quarterly, 4, 506–527.

Somers, M. J., & Birnbaum, D. (1998). Work-related commitment and job performance: It’s also the nature of the performance that counts.

Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19, 621–634.

Steers, R. M. (1977). Organizational effective-ness: A behavioral view. Santa Monica, CA: Goodyear.

Vandenberghe, C., Bentein, K., & Stinglhamber, F. (2004). Affective commitment to the organi-zation, supervisor, and work group: Antece-dents and outcomes. Journal of Vocational Be-havior, 64, 47–71.

Walker, A. G., & Smither, J. W. (1999). A five-year study of upward feedback: What managers do with their results matters. Personnel Psy-chology, 52, 393–423.

Wanous, J. P. (1980). Organizational entry: Recruitment, selection, and socialization of newcomers. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Watson, B. S. (1995). The intern turnaround.

Management Review, 84(June), 9–12.