A THESIS

Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Acquire a Sarjana

Sastra Degree in English Language and Literature

by: Amiin Rais 09211144035

ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE STUDY PROGRAM FACULTY OF LANGUAGES AND ARTS

v

Melalui perantaraan baca tulis, Tuhan mengajarkan kepada

manusia apa yang tidak diketahuinya (Q.S. Al-‘Alaq: 4-5).

Sebaik-baiknya orang adalah yang orang beriman, sebaik-baiknya

orang yang beriman adalah mereka yang berilmu, dan

sebaik-baiknya ilmu adalah ilmu yang bermanfaat.

‘Pengerjaan Skripsi’ yang terlalu lama hanya akan menunda anda

vi

I dedicate this work to:

my beloved mom, who has always given me great love, support, deep

understanding and honest prayers;

my sister Sovia Rahmawati, who was willing to be one of the respondents in this

research; and

all the English Language and Literature students, who may be interested to

vii

Alhamdulillahirobbil’alamin, praise and gratitude be only to Allah SWT,

the Glorious, the Lord and the Almighty, the Merciful and the Compassionates,

who has given blessing and opportunity for accomplishing this thesis. Greeting

and invocation are presented to the Prophet Muhammad SAW, who has guided

mankind to the right path blessed by Allah SWT.

I realize that it is impossible to finish this thesis without any help, support,

encouragement, and advice from others due to my limited knowledge. Thus, I

would like to express my deep sincere gratitude to:

1. my beloved mother (Aminati) and sister (Sovia Rahmawati) who always

give me the tremendous love, care, support and prayers to finish the

research paper;

2. my first and second consultants, Bapak Drs. Assruddin Barori Tou, M.A.,

Ph.D. and Bapak Andy Bayu Nugroho, SS. M.Hum who have patiently

given help, advices, guidance, corrections and willingness to me in

completing this thesis;

3. all of the lecturers in English Language and Literature Study Program of

Yogyakarta State University for their whole heartedly assistance in these

past seven years of study;

4. all of my friends in the English Language and Literature of 2009 who

cannot be mentioned here one by one, especially my classmates in H class

viii

Finally, I realize that this work is far from perfection. However, I hope

that this thesis can give some contribution to the solution of some of the

difficulties in Translation and Interpreting analysis. Therefore, it is open for all

criticisms and suggestions to improve or rectify matters of my writing skill in the

subsequence chance.

Yogyakarta, November 2016

ix

SL : Source Language

TL : Target Language

ST : Source Text

TT : Target Text

SE : Source Expression

TE : Target Expression

TQA : Translation Quality Assessment

Add : Additions

Sub : Subtractions

x

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TITLE ... i

APPROVAL SHEET ... ii

RATIFICATION SHEET ... iii

PERNYATAAN ... iv

MOTTOS ... v

DEDICATIONS ... vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... vii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ... ix

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... x

LIST OF TABLES ... xiii

LIST OF FIGURES ... xiv

ABSTRACT ... xv

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION ... 1

A. Background of the Problem ... 1

B. Identification of the Problem ... 3

C. Focus of the Research ... 5

D. Formulation of the Problem ... 6

E. Objectives of the Study ... 7

F. Significance of the Study ... 7

CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW ... 9

A. Theoretical Review ... 9

1. Translation ... 9

a. Notions of Translation ... 10

b. Types of Translation ... 11

c. Process of Translation ... 12

2. Interpreting ... 12

a. Notions of Interpreting ... 13

xi

3. Equivalence in Translation ... 19

a. Formal Equivalence ... 20

b. Dynamic Equivalence ... 20

a. Adjustment ... 22

4. Techniques of Adjustment ... 22

a. Additions ... 23

b. Subtractions... 31

c. Alterations ... 35

5. Translation and Interpreting Quality Assessment... 40

6. About the Seminar ... 42

a. The Speaker ... 43

b. The Interpreter ... 43

7. Related Studies ... 43

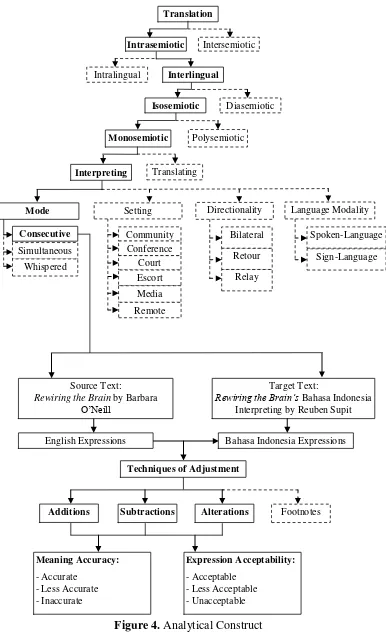

B. Conceptual Framework ... 45

1. Translation Definition ... 45

2. Translation Classification ... 45

3. Interpreting Definition ... 47

4. Interpreting Classification ... 47

5. Consecutive Interpreting ... 48

6. Techniques of Adjustment ... 48

7. Translation and Interpreting Quality Assessment... 50

8. Analytical Construct ... 55

CHAPTER III RESEARCH METHOD ... 57

A. Study Type ... 57

B. Data and Data Sources ... 57

C. Research Instruments ... 58

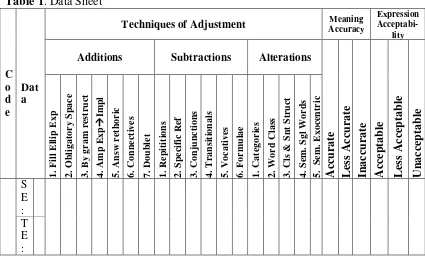

D. Data Collection Technique ... 62

E. Data Analysis Technique ... 62

xii

CHAPTER IV FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION ... 65

A. Findings ... 65

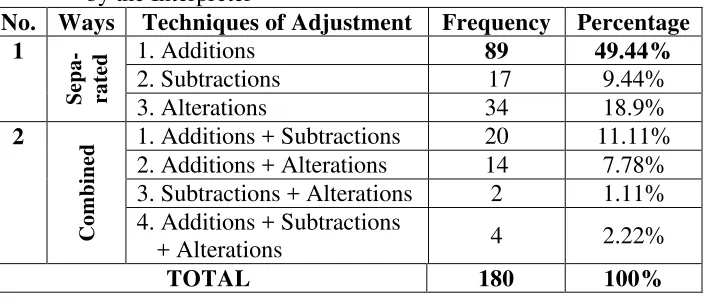

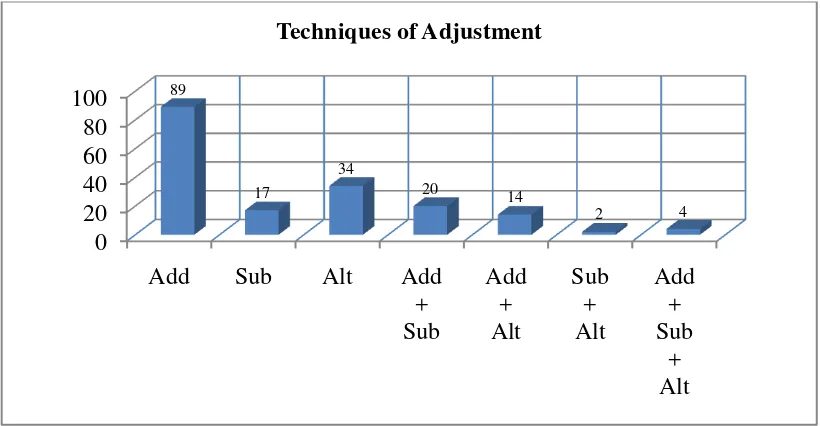

1. The Techniques of Adjustment Used by the Interpreter ... 65

2. The Meaning Accuracy of the Interpreting ... 66

3. The Expression Acceptability of the Interpreting ... 68

B. Discussion ... 69

1. Description of the Techniques ... 70

2. Description of the Meaning Accuracy ... 112

3. Description of the Expression Acceptability ... 118

CHAPTER V CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS ... 124

A. Conclusion ... 124

B. Suggestions ... 125

REFFERNCES ... 128

xiii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Data Sheet ... 58

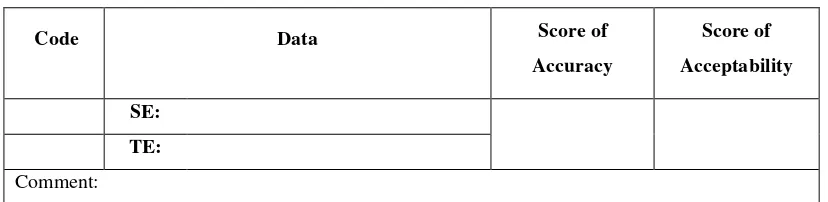

Table 2. Data Questionnaire ... 59

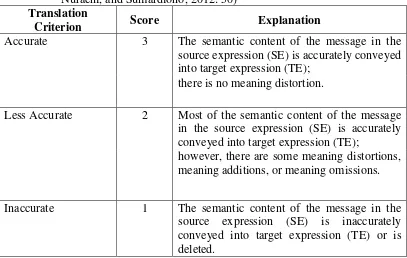

Table 3. The Accuracy Assessment Scoring System ... 60

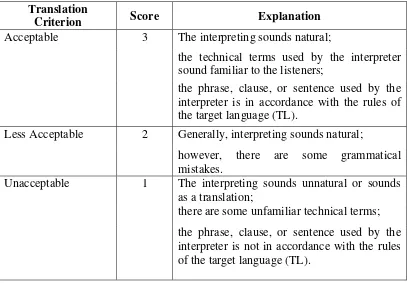

Table 4. The Acceptability Assessment Scoring System ... 61

Table 5. Frequency and Percentage of the Techniques of Adjustment Employed by the Interpreter ... 65

Table 6. The Frequency and Percentage of the Accuracy Levels ... 67

Table 7. The Frequency and Percentage of the Acceptability Levels ... 68

xiv

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Process of Translation ... 12

Figure 2. Adjustment among Formal and Dynamic Equivalence ... 22

Figure 3. Note-Taking for Consecutive Interpreting ... 48

Figure 4. Analytical Construct ... 56

Figure 5. Frequency of the Adjustment Techniques Employed by the Interpreter66 Figure 6.The Adjustment Techniques’ Effect on the Accuracy Levels ... 67

Figure 7.The Adjustment Techniques’ Effect on the Acceptability Levels ... 69

xv

THE TECHNIQUES OF ADJUSTMENT IN BARBARA O'NEILL'S SEMINAR ENTITLED REWIRING THE BRAIN AND ITS BAHASA

INDONESIA INTERPRETING BY REUBEN SUPIT By: Amiin Rais

NIM 09211144035

ABSTRACT

This study aims at 1) describing the techniques of adjustment employed by the interpreter; 2) describing the degrees of the meaning accuracy of the interpreting, using techniques of adjustment, produced by the interpreter in

O'Neill's seminar entitled Rewiring the Brain; and 3) describing the degrees of the

expression acceptability of the interpreting, using techniques of adjustment, produced by the interpreter in the seminar.

This research uses mixed methods as the research approaches, in which the qualitative method is the primary method and the quantitative method is the secondary one. The data were all the sentences or clauses showing that the interpreter uses techniques of adjustment. The data are collected from Barbara O’Neill’s seminar entitled Rewiring the Brain as the source text and its Bahasa Indonesia interpreting, by Reuben Supit, as the target text.

The result of this research shows there are seven techniques of adjustment consisting of three separated techniques and four combined techniques, they are: 1) additions, 2) subtractions, 3) alterations, 4) additions + subtractions, 5) additions + alterations, 6) subtractions + alterations, and 7) additions + subtractions + alterations. In terms of the meaning accuracy, 87 data (or 48.33%) are considered accurate, 92 data (or 51.11%) are considered less accurate, and 1 datum (or 0.56%) is considered inaccurate. From these percentages, the interpreting using the techniques of adjustment in the seminar is generally considered less accurate. Then, in terms of the expression acceptability, 96 data (or 53.33%) are considered acceptable, 81 data (or 45%) are considered less acceptable, and 3 data (or 1.67%) are considered unacceptable. From these percentages, the interpreting using the techniques of adjustment in the seminar is generally considered acceptable.

1 A. Background of the Problem

In general, there are three types of translation. They are written translation,

sign translation, and interpreting/oral translation. Written translation is the most

common type applied today. There are many books, journals, and novels which

are translated from English into Bahasa Indonesia or vice versa. Conversely, both

sign translation and oral translation are infrequently found rather than written

translation. In 1999 sign translation could be found in TVRI. It is very useful for

the deaf to get some information from television but today this activity rarely

exists. Sign translation was used in the live on air debates for the candidates of

president and vice president in general election 2014-2019. The number of people

who understand sign language is, however, fewer than the number of people who

do not. For some international situations such as international debates, seminars,

speeches, or in some courts which involve at least two different languages – sign

translation does not have too significant role but interpreting/oral translation

instead. In this case, interpreting is important and many interpreters are needed to

deal with such situation.

However, to be an interpreter is not easy and there are at least five reasons

in general. Firstly, the interpreter only has limited time to transfer ST into TT so

s/he cannot open any dictionary; s/he are not allowed to spend much time to think

Secondly, the interpreter has responsibility to convey all the information

from the ST to the TT immediately. It could be more problematic if the

source-text speaker has very high position and/or it deals with urgent situations.

Thirdly, since it is an interpreting/oral translation, the listeners or audience

only listen to what the interpreter is talking at that time. After s/he has finished

her/his speech, the audience will turn their concern to the next speech. It is very

different from reading text books or other written texts in which the readers can

reread what they have red. In this case, the interpreter is required to convey the

message as clearly as possible.

Fourthly, the type of the ST is oral text and it must be transferred into the

TT in oral text too. It needs ability of the interpreter to understand the message, to

determine the word choices, to arrange them, and to convey the messages into the

TT orally as well as the ST. The TT is expected to be presented in the same way

as the ST had been presented.

Last but not least, while the interpreter has already dealt with an

interpreting activity, s/he only uses her/his background knowledge to understand

and to convey the messages. For example, it is very difficult for people who do

not know about medicine or never hear any medical term to be an interpreter in a

medical seminar. If so, s/he will find many difficulties to recognize some medical

or chemical terms or even to understand the concept of the topic that the

source-text speaker conveys, and the possibility is that s/he cannot convey the message as

Interpreting activities could be found in some multicultural activities

which at least involve two different languages such as Seminars involving

English-Bahasa Indonesia or vice versa. Barbara O’Neil’s Seminar Kesehatan is

one of them. It was held in September 3-8, 2012. In this seminar, some medical

terms and concepts were often employed by the source-text speaker and they

made the interpreting activity often problematic. The limited time is also another

problem for the interpreter to listen, to think, to transfer, to reword and then to

convey the message to the audience.

B. Identification of the Problem

Seminar Kesehatan (Seminar of Health), held in September 3-8, 2012, was

a bilingual seminar (English-Bahasa Indonesia) in which both the source-text

speaker and the interpreter were in the same stage. The ST speaker’s name is

Barbara O’Neil, a qualified naturopath and nutritionist from New South Wales,

Australia, and the interpreter is the CEO/President at Bandar Lampung Adventist

Hospital (RS Advent Bandar Lampung), Dr. Reuben Supit. During this seminar,

the ST speaker had been speaking in English for several seconds then stopped her

speech, and then the interpreter had been interpreting it in Bahasa Indonesia soon,

and it would be the same way for the next speeches so it is called short

consecutive interpreting. In this interpreting activity, there are many problems

appearing and it might be caused by many factors such as the culture of the ST

speaker, the limited time, the speech’s rate of the ST speaker, and the specific

Since the speaker is an Australian, she tends to use Australian English

rather than British or American English. For people who do not familiar with

Australian English, it might be a problem since it is a little bit different from

British or American English. It could be different whether in vocabularies or

pronunciation.

Another problem is on the limited time. While on the stage, the interpreter

should interpret immediately what the ST speaker had said. Consequently, he did

not have enough time to correct his translation for the best quality because while

interpreting, to keep silence is not too expected since it shows that the interpreter

fails to interpret so it is better, for some reasons, to say something although it will

lose some messages. Therefore, there would be some additions, subtractions or

alterations of information in the TT and it becomes more problematic when the ST

speaker changed his speech’s rate suddenly.

The speaker, like other people, often changed her speech’s rate anytime in

which she could speak slowly or quickly suddenly. While the ST speaker was

speaking slowly, it could help the interpreter easily comprehend since there would

be many clear spelling. It could help the interpreter produce a good interpreting.

However, while the ST speaker was speaking quickly, some words or expressions

may be not heard clearly. If the interpreter was unfamiliar with the concept of the

topic, it would be problematic since he would not be able to predict any unfamiliar

term. It would be more problematic if the topic of the discussion was aimed at a

In this seminar, Seminar Kesehatan (Seminar of Health), there are sixteen sessions which were all discussing about health. It means that there would be

some medical terms mentioned by the ST speaker and it would be problematic if

the interpreter never heard about the terms. Also, he must know the meaning and

understand the working systems of some medical or even chemical terms.

Most importantly, the interpreting in this seminar seems problematic since

the interpreter often modifies the source expressions while interpreting by adding,

subtracting, and altering the message. These modifications are properly found in

Nida’s techniques of adjustment. It is susceptible for the content of the messages

to be distorted if they are added, subtracted, or altered. Accordingly, it is

significant to conduct a research of the Techniques of Adjustment in Barbara

O'Neill's Seminar Entitled Rewiring the Brain and its Bahasa Indonesia

Interpreting by Reuben Supit. Besides, the interpreting qualities in this seminar

are found problematic.

C. Focus of the Research

From sixteen sessions in Barbara O’Neil’s Seminar Kesehatan held in

September 3-8, 2012, this research focuses on the thirteenth session entitled

Rewiring the Brain. The researcher chooses this session since it does not have too long or too short duration of presentation. It has sixty four minutes duration which

is expected to be able to represent the whole interpreter’s performances during the

seminar in which all of the sixteen sessions in this seminar used the same speaker

same theme which was about health. In addition, this session has a lot of

information about human brain in which the audience was explained how to

rewire their brain by doing simple things such as playing music, reading, and

learning something new in everyday life. Most importantly, this session is chosen

as the object observed in this research since there are various deviations between

the source text (ST) and the target text (TT) which are quite problematic. The very

significant deviations are seen from the techniques of adjustment frequently used

by the interpreter, including: additions, subtractions, and alterations. Here, the

research concerns the analysis in the form of sentences since almost all the

sentences in the source text (ST) were adjusted by the interpreter. Therefore, this

research focuses on analyzing the techniques of adjustment occurring in the

thirteenth session of Barbara O’Neil’s Seminar Kesehatan, entitled Rewiring the

Brain and its Bahasa Indonesia interpretation by Dr. Reuben Supit.

D. Formulation of the Problem

Due to the ideas in the background of the problem above, the problems

under concern can be formulated as follows.

1. What techniques of adjustment are employed by the interpreter?

2. What are the degrees of the meaning accuracy of the interpreting, which uses

techniques of adjustment, produced by the interpreter in O'Neill's seminar

3. What are the degrees of the expression acceptability of the interpreting, which

uses techniques of adjustment, produced by the interpreter in O'Neill's

seminar entitled Rewiring the Brain?

E. Objectives of the Study

In line with the problems in formulation of the problem, this research

specifically aims at:

1. describing the techniques of adjustment employed by the interpreter;

2. describing the degrees of the meaning accuracy of the interpreting, which

uses techniques of adjustment, produced by the interpreter in O'Neill's

seminar entitled Rewiring the Brain; and

3. describing the degrees of the expression acceptability of the interpreting,

which uses techniques of adjustment, produced by the interpreter in O'Neill's

seminar entitled Rewiring the Brain.

F. Significance of the Study

This research offers some benefits, both theoretically and practically. It is

expected that the result can be advantageous in the following types of

significance.

1. Theoretical Significance

The result of this study is expected to give information and understanding

in consecutive interpreting from English to Bahasa Indonesia. Furthermore, the

interpreting research, especially in interpreting research since there are many

problems that could be observed. This research shows that the interpreter tends to

produce the expressions which are acceptable to the listener rather than to convey

the very accurate meaning. It can be seen from the findings that the techniques of

adjustment used by the interpreter are not only used separately (such as additions,

subtractions, and alterations) but also in combinations (such as additions +

subtractions, additions + alterations, subtractions + alterations, and additions +

subtractions + alterations). In fact, there are a few researchers who use

interpreting as their research objects. Therefore, the result of this study is also

expected to be a reference to the next relevant research.

2. Practical Significance

The result of this study is expected to give better understanding to English

Language and literature students especially who major in translation in order to

improve their ability in translation and especially in interpreting. It is a

combination of many skills such as listening skills, skills to comprehend, to

transfer source expression (SE) into target expression (TE) immediately, to

reword or restructure, to speak and or even to use body language skills. Therefore,

the result of this study is also expected to influence English and language students

9

CHAPTER II LITERATURE REVIEW

A. Theoretical Review

In this section, there are various explanations which are formulated in

several topics. Firstly, it explains translation in general. Secondly, it explains

interpreting as a form of translation in which it is the type of the data source.

Thirdly, it explains equivalence in translation as the basic orientation in

translation. Fourthly, it explains the „Techniques of Adjustment’ as the techniques

in which the researcher focuses on. Fifthly, it reviews some translation and

interpreting quality assessments. Sixthly, it briefly shows some information about

the seminar. Lastly, it reviews some related studies.

1. Translation

The activity of translations has been used since ancient times by humans

for communication, from one to each other who have different languages. The

condition of having difficulties to understand each other’s languages is considered

to be the cause of humans doing translation activities as the alternatives. The idea

about translation could refer to wide senses since one person’s perspective may be

different from other person’s perspectives in order to see translation, whether they

are from experts in such field or not. Therefore, to gain deeper explanations and

better understanding about translation, what must be known first is to know the

a. Notions of Translation

Notions of translation have wide senses depending to whose perspective it

refers. The notions of translation would be presented by involving some

definitions from various experts in translation field as follows.

Firstly, Catford (1965: 20) defines translation as “the replacement of

textual material in one language (SL) by equivalent textual material in another language (TL)." Similarly, Nida and Taber (1982: 208) define translation as “the reproduction in a receptor language of the closest natural equivalent of the source

language message, first in terms of meaning, and second in terms of style.” Then,

Brislin (1976: 1) defines translation as:

the transfer of thoughts and ideas from one language (source) to another (target), whether the languages are in written or oral form;

whether the languages have established orthographies or do not have such

standardization; or whether one or both languages is based on signs, as with sign languages of the deaf.

Here, it can be seen that translation can be in several forms, including:

written translation, interpreting, and sign-language interpreting. Then, Bell (1991:

13) defines translation into three distinct meanings:

(1) translating: the process (to translate; the activity rather than the tangible object);

(2) a translation: the product of the process of translating (i.e. the translated text); and

(3) translation: the abstract concept which encompassed both the process of translating and the product of that process.

Here, the terms „translation’ may refer to: the process (translating), the

product (a translation), and the abstract concept (translation). Meanwhile, House

which a text in one language is re-contextualized in another language.” This

definition implies that translation is a complex phenomenon.

b. Types of Translation

To know the definitions of translation in deeper explanations, it is

necessary to know the types of translation. Firstly, Jakobson (in Brower, 1959:

233) classifies three types of translation as follows.

1) Intralingual translation or rewording is an interpretation of verbal signs

by means of other signs of the same language.

2) Interlingual translation or translation proper is an interpretation of

verbal signs by means of some other language.

3) Intersemiotic translation or transmutation is an interpretation of verbal

signs by means of signs of nonverbal sign systems.

Meanwhile, Holmes (in Venuti, 2000: 178-179) classifies „human

translation’ into two types: interpreting/oral translation and written translation.

Further, by developing Jakobson’s translation classification (in Brower,

1959: 233), Gottlieb (2005: 3) classifies translation into several types based on

two main aspects. Firstly, based on semiotic identity or non-identity, translation is

classified into: intrasemiotic and intersemiotic types of translation. Secondly,

based on the possible change in semiotic composition, translation is classified

into: (a) isosemiotic (using the same channel(s) of expression as the source

text), (b) diasemiotic (using different channels), (c) supersemiotic (using more

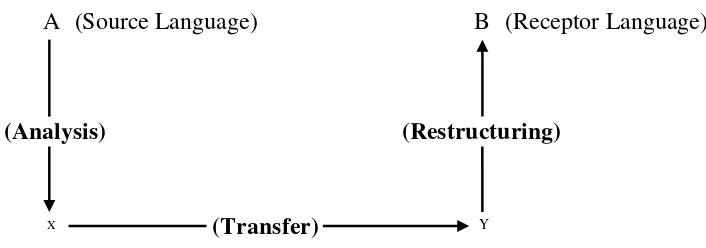

c. Process of Translation

Nida and Taber (1982: 33) states that process of translation consists of

three stages: 1) analysis, 2) transfer, and 3) restructuring. The phases can be

illustrated in a diagram as follows.

Figure 1 illustrates the process of translation from source language (SL)

into receptor language (RL) through three stages. Firstly, the translator must

analyze the message from language A (Source Language) in order to understand

the grammatical relationship, the meanings of words, and combinations of words.

Secondly, the translator transfers the analyzed messages, in his/her mind, from

language A (Source Language) into language B (Receptor Language). Thirdly, the

translator restructures the transferred messages into the final messages which are

fully acceptable in the receptor language (RL).

2. Interpreting

Before written language was invented, ancient people had already used

spoken language to communicate with each other. In a wide sense, spoken/oral

translation is also known as interpreting. However, interpreting may not always Figure 1. Process of Translation (Nida and Taber, 1982: 33)

(Transfer) (Analysis)

X Y

(Restructuring)

refer to oral translation since interpreting can be in another verbal form, such as

written text, or in non verbal form, such as sign language. Therefore, to gain

clearer explanations about interpreting, the notions and types of interpreting are

represented as follows.

a. Notions of Interpreting

Notions of interpreting encompass wide senses since the experts in

translation and interpreting define interpreting according to their different points

of view. Interpreting occurs “whenever a message originating orally in one

language is reformulated and retransmitted orally in a second language”

(Anderson, 1978: 218). In other side, Otto Kade (in Pöchhacker, 2004: 10) defines

interpreting as a form of Translation, in the way that: “the source-language text is

presented only once and thus cannot be reviewed or replayed, and the

target-language text is produced under time pressure with little change for correction and

revision.”

To be in line with Kade (in Pöchhacker, 2004: 10), Pöchhacker (2004: 11)

formulates what Kade defined into a simpler definition. The term „text’ in the

Kade’s definition is specified into the term „utterance’ by Pöchhacker. The

formulation states that: “Interpreting is a form of Translation in which a first and

final rendition in another language is produced on the basis of a one-time presentationof an utterance in a source language” (Pöchhacker, 2004: 11). Based on this definition, it can be seen that the form of interpreting is more in spoken

than in written or sign language. In addition, Nolan (2005: 2) defines interpreting

language and renders it orally, consecutively or simultaneously, in the target

language.”

To gain more specific definitions of interpreting, it is needed to bring the

definitions into further explanations covering various types of interpreting.

b. Types of Interpreting

Al-Zahran, in his Doctoral thesis (2007: 16), mentions some classifications

of interpreting based on four criteria: „mode’, „setting’, „directionality’, and

„language modality’.

1) Types of Interpreting in Terms of „Mode’

There are at least four modes of interpreting as follows.

a) Consecutive Interpreting

Consecutive interpreting is defined as a type of interpreting in which the

interpreter “listens to the speaker, takes notes, and then reproduces the speech in

the target language” and “this may be done all at one go or in several segments”

(Nolan, 2005: 3). In consecutive interpreting, the interpreter “starts to interpret

when the speaker stops speaking, either in breaks in the source speech … or after

the entire speech is finished” (Christoffels and de Groot in Kroll and de Groot,

2005: 45). In this mode, the interpreter deals with at least two phases: first

listening to the SL speaker for a view minutes and then reformulating the

speaker’s speech into TL (Gile in Schäffner, 2004: 11-12). In this mode, the

interpreter should wait, listen to what the speaker speaks, and then interpret it

the whole speech segment by segment. The interpreter is required to take notes

while the ST speaker is speaking, for example, during 15 minutes approximately.

b) Simultaneous Interpreting

Unlike the consecutive interpreting, the simultaneous interpreting does not

have any time to wait; instead, s/he should interpret continuously at the same time

the speaker speaks so s/he does not need to memorize large segment of the

original text. Gile (in Schäffner, 2004: 11) defines simultaneous interpreting as “a

mode in which the interpreter reformulates the source speech as it unfolds,

generally with a lag of a few seconds at most.” It implies that it is almost

impossible for the interpreter to interpret the SL segment without a lag at all.

Another statement comes from Paneth (1957: 32) stating that the “interpreter says

not what he hears, but what he has heard.” It is clear that the interpreter could

only interpret if s/he has heard the SE message. If s/he is able to say what s/he

hears or even what she does not hear yet, the possibility is that s/he does not

interpret but predict the words or messages the speaker is going to say. In

additions, in simultaneous interpreting, the interpreter, usually “sitting in a

soundproof booth, listens to the speaker through earphones and, speaking into a

microphone, reproduces the speech in the target language as it is being delivered

in the source language” (Nolan, 2005: 3).

c) Whispered Interpreting

According to Pöchhacker (2004: 19), whispered interpreting is considered

to be a variation of Simultaneous Interpreting. Although in whispered interpreting

simultaneous interpreting. While the simultaneous interpreter is working in a

soundproof booth, the whispered interpreter is “sitting behind a participant at a

meeting and simultaneously interpreting … only for that person” (Nolan, 2005: 4).

d) Sight Translation

According to Gile (in Schäffner, 2004: 11), in this mode, the ST is written

and the TT is spoken. The interpreter reads the written text first and then translates

it into spoken text. In addition, according to Pöchhacker (2004: 19), this mode is a

variant of „simultaneous interpreting’ and if it is immediately practiced in real

time it should be called „sight interpreting’.

2) Types of Interpreting in Terms of „Setting’

According to the setting, interpreting can be classified into six types as

follows.

a) Community Interpreting

According to Wadensjö (in Baker and Saldanha, 2009: 43), community

interpreting usually takes place in the public service environment, such as “police

department, immigration departments, social welfare centres, medical and mental

health offices, schools and similar institutions,” in which the interpreter acts as the

facilitator between officials and lay people.

b) Conference Interpreting

According to Gile (in Schäffner, 2004: 11), the work environment of this

form is “mostly at meetings organised by international organisations, by large

industrial corporations, by government bodies at a high level and for radio and

the most prestigious form of interpreting. Therefore, the interpreter is demanded

to have a high-quality performance in using both consecutive interpreting (CI) and

simultaneous interpreting (SI) (al-Zahran, 2007: 19).

c) Court Interpreting

According to Gile (in Schäffner, 2004: 11), the work environment of court

interpreting is “essentially at court proceedings.” However, it is not always used

in courtrooms, but it can also be used in “law offices or enforcement agencies,

prisons, police departments, barristers’ chambers or any other agencies to do with

the judiciary” (Mikkelson 2000: 1; Gamal 2001: 53; al-Zahran, 2007: 19).

d) Escort Interpreting

According to Mikkelson (cited by al-Zahran, 2007: 20), escort interpreting

is usually occurring “during on-site visits made by official figures, business

executives, investors, etc.” and the interpreter may deal with either formal or

informal situations. “CI is mostly used in this type of interpreting and is usually

limited to several sentences at one time” (Gonzalez et al. 1991: 28; al-Zahran,

2007: 20).

e) Media Interpreting

According to Pöchhacker, (2004: 15), media interpreting refers to

interpreting used in various broadcasts including television and radio and it is also

called „broadcast interpreting’ and „television interpreting’. It demands the

interpreter to have a good performance during the interpreting activity since it

would be listened and watched by various audience. In addition, the interpreter

f) Remote Interpreting

According to Pöchhacker (2004: 21), since the 1950s there has been a

form of remote interpreting called „telephone interpreting’ or „over-the-phone

interpreting’ which is considered to be the oldest form of remote interpreting. It

allows the interpreter to interpret from a distance and s/he cannot see the audience

because they are in a different place.

3) Types of Interpreting in Terms of „Directionality’

According to directionality, interpreting can be classified into three types

as follows.

a) Bilateral Interpreting`

According to Pöchhacker (2004: 20), bilateral interpreting requires the

interpreter to deal with two languages since the client could be the speaker and/or

audience. The interpreter should be able to transfer the message from Language 1

(L1) into Language 2 (L2) and vice versa.

b) Retour Interpreting

According to Jones (1998: 134), when the interpreter interprets from

her/his native language (Language A) into her/his foreign language (Language B),

it is called retour interpreting. When the interpreter deals with, for example,

cultural terms, s/he would be considered to be more culturally competent in their

mother language than in their foreign language.

c) Relay Interpreting

“Relay interpreting is defined as „a mediation from source to target

than that of the original’” (Dollerup cited in al-Zahran, 2007: 24). This situation is

occurring if one of the interpreters, in a conference, does not understand several

languages used at that time and then s/he asks another interpreter to interpret what

the speaker has said. Therefore, the quality of interpreting, in this situation, is poor

because what s/he interprets is an interpreting product, not the original one.

4) Types of Interpreting in Terms of „Language Modality’

Based on language modality, interpreting is classified into two types:

„spoken-language interpreting’ and „signed-language interpreting’ (Pöchhacker,

2007:17). In spoken-language interpreting, the interpreting uses verbal language

to transfer the message from source language (SL) into target language (TL), for

example: from English to Bahasa Indonesia, Spanish to Dutch, Japan to English,

etc. Then, in sign-language interpreting, the interpreting uses non verbal language

to transfer the message from source language (SL) into target language (TL). It is

usually used in communications to deaf people. It is used, for example, if a

speaker, who does not understand sign-language, wants to communicate to deaf

people.

3. Equivalence in Translation

In written translation or interpreting, the term „equivalence’ is always

involved and it has a very significant role since it is what translators or

interpreters actually need to achieve. However, the term „equivalence’ is still

problematic if the translators or interpreters do not know what types of

are fundamentally two different types of equivalence: one which may be called

formal and another which is primarily dynamic.”

a. Formal Equivalence (FE)

In formal equivalence, the translators or interpreters focus their attentions

“on the message itself, in both form and content” (Nida in Munday, 2001: 41).

The aim of this formal equivalence (FE) is to “bring the reader [or listener] nearer

to the linguistic or cultural preferences of the ST” (Hatim and Munday, 2004: 42).

This form of equivalence is properly used, for example, in translating texts for

foreign language learners so they can compare the source language’s structures

with the target language’s structures. According to Nida (1964: 159), the

translation type which has the characteristic of this structural equivalence (or

formal equivalence) may be called a “gloss translation,” in which the translator

tries to produce a translation by preserving the form and content of the original

text as literary and meaningfully as possible. Translating using FE, however,

makes the text sound less or unnatural since the readers would realize that what

they have red or listened to is a translation or interpreting product.

a. Dynamic Equivalence (DE)

While formal equivalence (FE) is faithful to the source text, dynamic

equivalence (DE) is not so. In dynamic equivalence, the translators or interpreters

do not too orientate on the form but on the naturalness of the target text so the

readers may forget or do not realize that what they have red or listened to is

actually a translation or interpreting product (Nida in Munday, 2001: 42). To be in

equivalence’ as: “A translation which preserves the effect the ST had on its

readers and tries to elicit a similar response from the target reader.” The aim of

DE is to produce “complete naturalness of expression, and [it] tries to relate the

receptor to modes of behavior relevant within the context of his [or her] own

culture” (Nida, 1964: 159). Based on such explanations, it can be implied that

dynamic equivalence (DE) tries to make the target readers experience the same

effect as the original. This form of equivalence is properly used when “form is not

significantly involved in conveying a particular meaning, and when formal

rendering is therefore unnecessary” (Hatim and Munday, 2004: 43).

Both formal and dynamic equivalence are not absolute translation

techniques “but rather general orientations” (Hatim and Munday, 2004: 43). To

decide whichever kind of equivalence will be used “must always be „contextually

motivated’” (Hatim and Munday, 2004: 253). „Unmotivated formal equivalence’

will be regarded as translating without considering/knowing the ST culture,

whereas „unmotivated dynamic equivalence’ will be regarded as „blatant

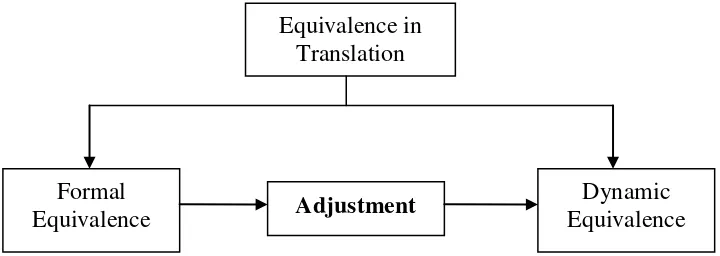

re-writing’ (Hatim and Munday, 2004: 253). b. Adjustment

While both formal equivalence (FE) and dynamic equivalence (DE) deal

with “why the translator does one thing or another” to a translation, „adjustment’

deals with “what he does” to a translation (Nida, 1964: 226). Both FE and DE

cannot be separated from „adjustment’ since it can be in both FE and DE.

gradual move away from form-by-form renderings and towards more dynamic

kinds of equivalence.” This definition can be illustrated as follows.

While both FE and DE are categorized as general translation orientations,

„adjustment’ is categorized as “an overall translation technique which may take

several forms” (Hatim and Munday, 2004: 43). The explanations about the

techniques under the umbrella of adjustment are addressed in the next topic

(Techniques of Adjustment).

4. Techniques of Adjustment

Nida (1964: 226-238) there are several techniques called as „techniques of

adjustment’ to help translators produce correct equivalents. They are additions,

subtractions, and alterations. In terms of equivalence, these techniques tend to be employed in a translation orientated toward dynamic kind of equivalence. There

are at least four basic purposes of these techniques: “(1) permit adjustment of the

form of the message to requirements of the structures of the receptor language; (2) Formal

Equivalence Adjustment

Dynamic Equivalence Equivalence in

[image:37.595.136.496.148.276.2]Translation

produce semantically equivalent structures; (4) provide equivalence stylistic

appropriateness; and (4) carry an equivalent communication load” (Nida, 1964:

226). In addition to those three techniques, footnotes is included by Nida as

another technique of adjustment in which it has two main functions: “1) To

correct linguistic and cultural differences” and “2) To add additional information

about the historical and cultural context of the text in question” (Molina and

Hurtado Albir, 2002: 502). While additions, subtractions, alterations tend to be

used in DE translation, footnotes tends to be used in FE translation.

Considering that this research deals with interpreting, the further

explanation does not explain footnotes (since it is only used in written translation)

but additions, subtractions, and alterations. a. Additions

According to Nida (1964: 227), there are at least nine types which are

considered to be the most common and important types of additions. They include

the following types: 1) filling out elliptical expressions, 2) obligatory

specification, 3) additions required by grammatical restructuring, 4) amplification

from implicit to explicit status, 5) answer to rhetorical questions, 6) classifiers, 7)

connectives, 8) categories of the receptor language, and 9) doublets. Some of

these techniques are “a part of the process of structural alteration” so it is

important to notice that one technique cannot totally be separated from another

1) Filling Out Elliptical Expressions

According to Nida (1964: 227), although ellipsis is a common

phenomenon occurring in all languages, the particular structures which allow for

omitting some words are not always the same from language to language.

Therefore, while an elliptical expression is required in one language, “an ellipsis

may not be permitted in another” (Nida, 1964: 227). The example is presented as

follows.

SE: She is more beautiful than I.

TE: Dia lebih cantik daripada aku yang cantik.

[She is more beautiful than I am beautiful.]

The Subject „I’ in the SE is transferred into „aku yang cantik’ in the TE

which means „I am beautiful’. There is an addition „yang cantik’ („am beautiful’)

in the TE which do not exist in the SE. The use of the word „I’ indicates that it is

an elliptical expression in which the use of the word „I’ instead of „me’ indicates

that the subject „I’ is actually beautiful but the subject „she’ is more beautiful.

2) Obligatory Specification

There are two reasons why it is required to add some specifications: a) to

avoid ambiguity in the target language formations and b) „to avoid misleading

reference’ (Nida, 1964: 228).

The first example is the addition in order to avoid ambiguity in the target

SE: “they tell him of her” (Mark I: 30; Nida, 1964: 228; emphasis added).

TE: Orang-orang di sana menceritakan kepada Yesus tentang wanita

tersebut.

[“the people there told Jesus about the woman”] (Nida, 1964: 228;

emphasis added).

The second type is the addition in order to avoid misleading reference. The

example is presented as follows.

SE: John is trying to run away.

TE: Aku, John, sedang mencoba melarikan diri.

[I, John, am trying to run away.]

In the first example, to avoid ambiguity in the TE, the word „they’, „him’,

and „her’ in the SE are transferred into the TE as „orang-orang di sana’, „Yesus’,

and „wanita tersebut’ which in English mean „the peoplethere’, „Jesus’, and „the

woman’. It can be problematic if, for example, the word „him’ and „her’ are

translated as „nya’ and „nya’since the word „nya’ in the TE may refer to „him or

her’.

In the second example, the speaker whose name is „John’ tells about

himself in the SE without showing that „John’ is actually himself. However, this

elliptical expression could emerge a misleading reference if the reader or hearer

does not know the speaker’s name. Therefore, the word „aku’ in the TE, which

means „I’, is added to show the target reader or hearer that „John’ is the speaker

3) Additions Required by Grammatical Restructuring

According to Nida (1964: 228), although there is usually some „lexical

additions’ emerging as results of „restructuring’ of a SL expression, the most

common situation requiring amplification are as follows.

a) Shifts of Voice

It is needed to insert agent when a passive voice is changed into an active

one (Nida, 1964: 228). The example is presented as follows.

SE: He will be arrested for drinking. (passive voice)

TE: Polisi akan menahannya karena mabuk. (active voice)

[Police will arrest him for drinking]

Although there is no information about who will arrest „him’ in the SE, the

sentence is still meaningful since it is expressed in a passive voice. However,

when the passive voice in the SE is changed into active voice in the TE, it is

required to add information about who will arrest „him’. In this case, who will

arrest is „polisi’ („police’) since the context is related to criminality.

b) Modification from Indirect to Direct Discourse

It must often be necessary to add „a number of elements’ when „indirect

discourse, whether explicit or implicit, is changed into direct discourse’ (Nida,

1964: 228). The example is presented as follows.

SE: He can go home now. (indirect discourse)

TE: Dikatakan kepadanya, “kamu bisa pulang sekarang.” (direct

[Said to him, “you can go home now.”]

The phrase „dikatakan kepadanya’ („said to him’) in the TE is required to

be added because of the modification from indirect discourse in the SE into direct

discourse in the TE.

c) Alteration of Word Classes

Additions must mostly be made when there is a word class’ shift such as a

change from adjective to another word class or “a change from nouns to verbs”

which “produces some of the most radical additions” (Nida, 1964: 228). The

example is presented as follows.

SE: False presidents

TE: Mereka yang berpura-pura mejadiseorang presiden

[Those who pretend the work of a president]

The adjective „false’ in the SE is changed into noun clause „orang yang

berpura-pura’ in the TE which in English means „those who pretend’.

4) Amplification from implicit to explicit status

If the ST/SE has an implicit status and the TT/TE has an explicit status,

there must often be some additions in the TT/TE. This explicit identification

would become pivotal if there are some „important semantic elements’ which is

implicitly conveyed (Nida, 1964: 228). The example is presented as follows.

SE: I hate dirty places so I choose this room. (implicit)

TE: Saya benci akan tempat-tempat kotor, jadi saya pilih ruangan ini

karena di sini bersih. (explicit)

In the SE, there is no explicit information why the speaker chooses that

room. However, there is implicit information why s/he chooses that room. The

implicit information is on the clause „I hate dirty place’ indicating that the speaker

will not choose any dirty place. Therefore, the clause „karena di sini bersih’,

which in English it means „because it is clean’, is added in the TE to show the

explicit information of the SE.

5) Answers to Rhetorical Questions

Generally, it is not necessary to answer any rhetorical questions, but “in

some languages rhetorical questions always require answer” (Nida, 1964: 229).

The example is presented as follows.

SE: Do you want to go to hell?

TE: Apa kalian mau masuk neraka? Tentu tidak!

[Do you want to go to hell? No, indeed!]

The question „Do you want to go to hell?’ is something that does not need

to be answered since there is nobody wants to be in hell actually. Although it does

require any answer, it is also allowed to answer it. The answer may be from the

person who has asked the rhetorical question or from the person who was asked.

In the example above, the answer „Tentu tidak!’ in the TE, which means „No,

Indeed!’ in English, is from the questioner.

6) Classifiers

It is usually used to translate „proper names’ or „borrowed terms’ (Nida,

SE: He cannot speak English.

TE: Dia tidak bisa berbicara bahasa Inggris.

[He cannot speak English language.]

To add the word „language’, as a noun head, after the word „English’ in the

SE is not required since the word „English’ in the SE actually refers to the

language. In other side, it is necessary to add a classifier in the TE. The word

„bahasa’ in the TE which means „language’ is added, as a noun head, after the

word „Inggris’ to clarify that what the speaker means in the TE is referring to the

language, not the people.

7) Connectives

It occurs when there is a “repetition of segments of the preceding text”

called “Transitionals” in the TT/TE which can make it longer than the ST/SE “but

do not add information” (Nida, 1964: 230). The example is presented as follows.

SE: I want to finish reading this novel. And I will give it to you.

TE: Aku mau menyelesaikan membaca novel ini. Dan setelah selesai

membaca, aku akan kasihkan ke kamu.

[I want to finish reading this novel. And after finishing reading, I

will give it to you.]

In the SE, the meaning is that the speaker will not give the novel before

s/he has finished reading it and she will give it to the subject „you’ after s/he has

finished reading. The SE expressions are emphasized in the TE by adding the

connective „setelah selesai membaca’ which in English means „after finishing

8) Categories of the Receptor Language

When there are certain categories in the TT/TE which do not exist in the

ST/TE, whether they are obligatory or optional, it is necessary to add them in the

TT/TE (Nida, 1964: 230). The example is presented as follows.

TE: I meet your mother.

SE: Aku sudah bertemu ibumu.

In this example, the verb „meet’ is translated into Bahasa Indonesia as

„sudah bertemu’. Here the adverb „sudah’ is obligatory added to show that the

activity is the past tense.

9) Doublet

The use of doublet in some languages is frequent or even obligatory since

its function, for example, is almost like quotation marks (Nida, 1964: 230). It

denotes or re-expresses the previous „semantically supplementary expression’

occurring in one place such as „answering, said’, „asked and said’ or „he

said…said he’ (Nida, 1964: 230). The example is presented as follows.

SE: He said, “I love you.”

TE: Dia bilang, “Aku cinta kamu,” katanya.

[He said, “I love you,” said he.]

Doublet usually occurs in oral conversations in which some words,

phrases, or clauses are consciously or unconsciously repeated within a sentence.

In the example above, there is an addition the word „katanya’ („said he’) in the TE

The nine techniques mentioned above are considered to be the most

common and important types of „additions’ used in translation and interpreting.

Besides, it is important to remember that these techniques do not add any

“semantic content of the message” such as in changing from implicit to explicit

status, it just changes an implicit ST/SE into an explicit TT/TE so it just change

the way to communicate from the ST into the TT, not to the content (Nida, 1964:

231).

b. Subtractions

Nida (1964: 231-233) mentioned seven basic types of subtractions: 1)

repetitions, 2) specification of reference, 3) conjunctions, 4) transitional, 5)

categories, 6) vocatives, and 7) formulate.

1) Repetitions

In some languages repetitions are needed but in some other languages they

are misleading (Nida, 1964: 231). Therefore, one of the pair must be reduced. This

type of subtractions is the opposite of the „doublet’, one out of nine types of

additions’. The example is presented as follows.

SE: He said, “I love you,” said he.

TE: Dia bilang, “Aku cinta kamu.”

[He said, “I love you.”]

The clause „said he’ in the SE, which is equal to „He said’, is not

translated in the TE since it is considered that repetition is not needed in the TE.

The clause „Dia bilang’ in the TE, which means „He said’, is equally representing

2) Specification of Reference

Although an addition of elements is often required to make an implicit

reference in the ST/SE more explicit in the TT/TE, since every language has its

own way to express the reference, there is also an opposite situation (Nida, 1964:

231). The example is presented as follows.

SE: Jane is crying because she feels sad.

TE: Jane menangis karena merasa sedih. [Jane is crying because of feeling sad.]

Since it is clear that who feels sad is Jane, the specific reference „she’ in

the SE can be omitted in the TE.

3) Conjunctions

There are two principal types of conjunctions that are lost: a) “those

associated with hypotactic constructions…and b) those which link co-ordinates,

element often combined without conjunctions, either in appositional relationships”

(Nida, 1964: 232).

Here is an example of subtraction from hypotactic into paratactic

construction as follows.

SE: I am hungry, so that I buy a pizza.

TE: Aku lapar, aku beli pizza. [I am hungry, I buy a pizza.]

Here is an example of subtraction in terms of co-ordinates element as

SE: Jack and George and Jane TE: Jack, George, Jane

In the first example, the sentence in the SE consists of independent and

dependent clause. The clause „I am hungry’ is the independent clause, whereas „so

that I buy a pizza’ is the dependent clause. This SE construction is classified as

hypotaxis. In this construction, the conjunction „so that’ is the key word indicating

that this sentence uses hypotactic construction. In other hand, the conjunction „so

that’ is omitted in the TE so the TE construction is classified as parataxis in which

both clauses „Aku lapar’(„I am hungry’) and „aku beli pizza’ („I buy a pizza’) are

independent clauses.

In the second example, the conjunctions „and’ in the SE are omitted in the

TE. This omission occurs since it is considered that the TE still has equal meaning

to the SE. Another example is such as to omit the conjunction „but’ between two

independent clauses „I miss you but I hate you’ into „I miss you, I hate you’.

4) Transitionals

Transitionals are different from conjunctions since their functions are just

“to mark a translation from one unit to another” (Nida, 1964: 232). The example

is presented as follows.

SE: You have done some very hard works. Therefore, you can rest for a

days.

TE: Kalian sudah melakukan pekerjaan yang sangat berat. Kalian boleh itirahat sehari.

The transition „therefore’ in the SE is omitted in the TE. Although there is

no transition in the TE, it still has equal meaning to the SE.

5) Categories

Although some translators think that it is necessary to translate all

categories from the ST/SE into the TT/TE, not all categories are suitable to be

translated (Nida, 1964: 232). Therefore, some of them must be omitted to make

the TT/TE more natural. The example is presented as follows.

SE: I am walking now.

TE: Saya sedang berjalan. [I am walking.]

The word „now’ in the SE is omitted in the TE since the sentence „saya

sedang berjalan’ („I am walking’) has already represented that the subject „I’ is

walking „now’. In this case, the TE still has equal meaning to the TE even without

translating the word „now’.

6) Vocatives

Although every language has their own way to call people, in some

languages there is no way to call someone in a polite form. Therefore, some items

in the ST/TE which have no equal meaning in the TT/TE must be omitted. This

type of subtractions is the opposite of the „categories of the receptor language’,

one out of nine types of additions’. The example is presented as follows.

SE: Aku mau bertemu kak Intan.

[I want to meet kak(to address an older person) Intan]

While in the SE, it is required to use some proper name such as „kak’ to address an older person even in if the context is in a children conversation. In

other hand, the TE does not require any proper name to address an older person if

the context is in children conversation such as the conversation between a twelve

year old boy/girl and a fourteen year old boy/girl.

7) Formulae

Some formulae in the SE may not be employed in the TE since it is

already clear enough without using formulae. The example is presented as

follows.

SE: “… in His name” TE: “… oleh-Nya”

[“… by Him”]

The word „name’ in the SE is not translated in the TE. The pronoun „Nya’

in the TE, which in English means „Him’, equally represents the phrase „his name’

since the word „Nya’ uses first capital letter which refers to God.

c. Alterations

Alterations can occur in various types of texts or situations. It can occur in simplest elements such as alteration by different sounds to the most complicated

elements such as alterations by different idiomatic expressions. Besides, some

types of additions can actually be classified as structural alterations (Nida, 1964:

227). If some additions can be classified as structural alterations, it means that

both additions and subtractions seem as an opposing pair. Consequently, there

may be some similar combinations of additions or subtractions in alterations.

1) Sounds

While translating, if there is a unique object, the adjustment is by changing

the sound and still remaining such character of the object (Nida, 1964: 233). It is

considered to be the smallest form of alterations. The example is presented as

follows.

SE: Voltage /vɒl.tɪdʒ/

TE: Voltase /vɒl.tʌ.sə/

In the example above, both words „voltage’ and „voltase’ have different

sounds but still represent similar characteristics. In this research, this type of

alterations is not included for analysis since the focus of this research is in the

level of sentence.

2) Categories

Alteration of categories is caused by several conditions, such as shift from

singular to plural, past tense to future, and active voice to passive. The example is

presented as follows.

SE:If you let the vine do whatever wants it goes everywhere.

TE: Kalau tanaman rambat itu tidak dikendalikan maka ia akan merayap ke segala penjuru.

[If the vine is not controlled, it will go everywhere]

There is a change from active voice to passive in which the clause „If you

into the clause „Kalau tanaman rambat itu tidak dikendalikan’ („If the vine is not

controlled’) in the TE, which is a passive voice. Although there is a change from

active voice to passive, the meaning is still equal.

3) WordClasses

It occurs when there are some changes of word classes, such as shifts from

noun to verb, verb to adverb, etc. The example is presented as follows.

SE: He gave mankind choice.

TE: Dia memberikan kepada manusia kemampuan untuk bisa memilih. [He gave mankind the ability to choose]

The word „choice’ in the SE is changed into the phrase „kemampuan untuk

bisa memilih’ which in English means „the ability to choose’. The change or shift is from word to phrase. Although the form is changed, the meaning is still the

same.

4) Order

There are many situations in which the order of words is not too vital

actually (Nida, 1964: 235). However, it can be important if the purpose is to

produce a natural translation or interpreting (Nida, 1964: 235). The example is

presented as follows.

SE: There are, however, some mistakes you do not know.

TE: Akan tetapi, ada banyak kesalahan yang kamu tidak tahu.

[However, there are some mistakes you do not know.]

In the example above, the adverb „however’(in the SE) or „akan tetapi’ (in

the sentence; while in the TE, the adverb is placed in the beginning of the

sentence. In this research this type of alteration is not included for analysis since it

considered to be not significant in changing the meaning which means that it is

commonly used in interpreting.

5) Clause and Sentence Structures

There are at least two conditions in which a translator or interpreter is

allowed to do some alterations. Those two conditions are as follows.

a) Shift from Question to Statement

Here, the alteration can be from question to statement or vice versa. The

example is presented as follows.

SE: Can you sing me a love song?

TE: Aku ingin kamu menyanyikan aku sebuah lagu cinta. [I want you to sing me a love song]

The SE is a question indicated by the words „Can you’, in the first

sentence, in which the speaker’s purpose is to ask, for example, a singer to sing a

love song. In this case, the speaker actually knows that the person s/he asks is able

to sing so the question is categories as a request. Since the translator or interpreter

knows that the speaker’s purpose is actually to request, the question form in the

SE is changed into a statement form in the TE. Clearly, the words „Can you’ in the

SE is changed into „Aku ingin kamu’ which in English means „I want you to’.

b) Change Indirect Discourse to Direct

Here, the alteration can