Business Process Management Journal

Business process management : est ablishing and maint aining proj ect alignment Simon Box Ken Platts

Article information:

To cite this document:Simon Box Ken Platts, (2005),"Business process management: establishing and maintaining project alignment", Business Process Management Journal, Vol. 11 Iss 4 pp. 370 - 387

Permanent link t o t his document :

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/14637150510609408

Downloaded on: 19 March 2017, At : 20: 34 (PT)

Ref erences: t his document cont ains ref erences t o 45 ot her document s. To copy t his document : permissions@emeraldinsight . com

The f ullt ext of t his document has been downloaded 5064 t imes since 2006*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

(2003),"Managing the project management process", Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 103 Iss 1 pp. 39-46 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02635570310456887

(2014),"Understanding project success through analysis of project management approach", International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, Vol. 7 Iss 4 pp. 638-660 http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/

IJMPB-09-2013-0048

Access t o t his document was grant ed t hrough an Emerald subscript ion provided by emerald-srm: 602779 [ ]

For Authors

If you would like t o writ e f or t his, or any ot her Emerald publicat ion, t hen please use our Emerald f or Aut hors service inf ormat ion about how t o choose which publicat ion t o writ e f or and submission guidelines are available f or all. Please visit www. emeraldinsight . com/ aut hors f or more inf ormat ion.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and pract ice t o t he benef it of societ y. The company manages a port f olio of more t han 290 j ournals and over 2, 350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an ext ensive range of online product s and addit ional cust omer resources and services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation.

*Relat ed cont ent and download inf ormat ion correct at t ime of download.

Business process management:

establishing and maintaining

project alignment

Simon Box

Southam, Warwickshire, UK, and

Ken Platts

Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge,

Mill Lane, Cambridge, UK

Abstract

Purpose– The aim of the research was to develop a model for establishing and maintaining alignment of purpose in business change initiatives.

Design/methodology/approach– The research methodology combined a synthesis of the literature across the diverse fields of change leadership, project management, and organisational alignment; and a parallel analysis of two industrial case studies.

Findings– From an analysis of the cases, and a synthesis of the literature, a Project Alignment Model was developed. To help industrial project leaders operationalise the model and hence maintain alignment in their projects, the key points from the Project Alignment Model are also presented as a checklist.

Practical implications– Managing change is increasingly relevant for all industries and companies, and the rate of change is predicted to increase. Project managers in this environment must have more than just technical delivery skills; they need to be good leaders, capable of influencing strategic direction, and skilled in managing the political dimensions of their projects. The model presented will help these leaders improve their change management capability.

Originality/value– The developed model can be useful both as a descriptive model and as a prescriptive model. Used descriptively, the model can help structure the analysis of change projects. As such it could be a useful research instrument. Academics could use the model to analyse change projects and structure their findings in a way that allows ready cross-case comparisons. Such an approach can, by categorisation, lead to a more detailed understanding of the factors affecting project alignment and successful change. Used prescriptively, the model can guide project managers in creating and maintaining project alignment, and in doing so increase their chance of success in implementing change.

KeywordsProject management, Strategic alignment, Business process re-engineering, Change management

Paper typeResearch paper

Introduction

Managing change is increasingly relevant for all industries and companies, and many observers predict that change will only continue to increase (Kotter, 1996; Pendlebury

et al., 1998). However, companies are often unable to manage change well, and success rates as low as 20-30 per cent have been quoted (Strebel, 1998; McCune, 1999).

A successful change project demands competent change management. This involves not only a charismatic project manager but also alignment of purpose of everyone involved with the overall change initiative (Kotter, 1996). This alignment needs to be both internal within the project team, and external between the project The Emerald Research Register for this journal is available at The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/researchregister www.emeraldinsight.com/1463-7154.htm

BPMJ

11,4

370

Business Process Management Journal

Vol. 11 No. 4, 2005 pp. 370-387

qEmerald Group Publishing Limited 1463-7154

DOI 10.1108/14637150510609408

and the rest of the organisation. According to Molden and Symes (1999), if teams consist of individuals aligned with one another, and if they are aligned with the goals of the organisation, then their fullest potential can be deployed. Alignment allows the maximum energy and effectiveness to flow into achieving the desired outcomes.

Problems caused by misalignment include: confusion; waste of time, money and opportunity; diminished productivity; de-motivation of individuals and teams; internal conflicts and power struggles and ultimately project failure. Misalignment results in time and energy spent doubting, conspiring, guessing or gossiping when that same energy could be deployed in moving an organisation forward.

The literature on change management and project management has been well populated with topics related to aspects of alignment. For example, creating a guiding coalition, communicating a change vision, and changing the underlying systems or structures that undermine the change vision (Kotter, 1996); stressing the importance of involving the employees affected by a change in the change process (Axelrod, 2000; Carnall, 1999) ensuring there is participation and communication (Spiker, 1995). We believe that combining these principles with organisational alignment models such as Molden and Symes’ (1999) Universal Alignment Model, and Labovitz and Rosansky’s (1997) model, will provide a useful model to guide managers faced with establishing and maintaining project alignment.

This paper combines literature review with the findings from two industrial case studies to develop a model for establishing and maintaining alignment of purpose for business change initiatives. The model can be used by means of a prescriptive checklist intended to help project leaders increase their chances of success in implementing change.

Research methodology

There are two strands to our research: a synthesis of the literature across the diverse fields of change leadership, project management, and organisational alignment; and a parallel analysis of two industrial case studies. The two case studies were of projects aimed at significant changes in a company’s business processes. Projects A and B ran at the same time in the same group of companies, and were therefore, subject to the same approval criteria and executive oversight. However, Project A was a failure, while Project B was a success.

Using the analysis of these cases, and a synthesis of the literature, we developed a Project Alignment Model, which is presented in this paper. Rather than treat the literature and the cases separately, we combine both in a discussion of the aspects of our model. Thus, the structure of the paper is as follows. First, we present a brief description of the two cases. We then present our Project Alignment Model. Subsequently we discuss the detail of the model, showing how it has been developed from a synthesis of the literature and the two considered cases. Finally, we summarise the key points of the model as a checklist which is intended to guide project leaders in creating and maintaining project alignment.

The industrial cases

Project A

Project A was conducted in a traditional UK manufacturing company (Company A). It was initiated following a review that identified many improvement opportunities,

Business process

management

371

involving fundamental changes to most business processes and supporting IT systems. An implementation plan with aggressive timescales was chosen. The promise of quick benefits and the evangelical personality of the project manager helped to secure funding for the project.

Problems were experienced when the project was launched, as the vision had not been discussed with or accepted by Company A’s senior managers, many of whom refused to support it. The operations director left the company shortly after launch and was not replaced for several months, leaving operations unrepresented on the executive team. This was a problem because most of the changes were planned for that area of the company.

As the project continued, some parent group executives became nervous. They were concerned about the scope of the project, the weak business ownership, the rapid pace of the proposed change, and the inappropriate benefits case – there was no apparent dependency between the promised benefits, the proposed solution and the company’s strategy.

It soon became apparent that Company A was in a politically difficult situation, having made large promises to its parent company without an adequate or well-supported solution to deliver them. Project A was becoming a liability and the project manager was removed. A new sponsor was appointed, who in turn appointed a new project manager. Together they agreed to restructure the project with a robust business case and executive support. They agreed to withhold any spending until they were sure that absolute clarity of purpose had been defined and agreed. Key to the company’s survival was dramatic cost reduction in line with a falling market for its products, so they changed the project goals to focus on this.

However, at this time the project team was still committed to the original purpose. For several months they had continued with the original project plan, only vaguely aware of the underlying political problems. They had already prepared a blueprint design and were frustrated because they could not get money released to buy hardware and consultancy support. In reality, the original project was dead in everything but its name. The new project manager therefore took the project back to basics with another process mapping exercise. This developed a model of the ideal future state, which identified a number of potential quick wins and actually confirmed the viability of most elements of the original vision. Some of the elements were delivered immediately as “quick wins”. The project was split into three new projects, each of which delivered part of the original purpose. Two of these could begin immediately without any need for funding, and they began to establish the project team’s credibility. The third project is currently being pursued under a new name and will probably be completed over a year later than originally intended.

Project B

Company B is another UK manufacturing company, which had grown through acquisition, but had seen its market share decline in recent years. The company’s ability to increase market share through strengthening marketing and sales activities was constrained by complex business processes, obsolete computer hardware and unsupported software systems.

Project B was originally conceived to replace the company’s ageing IT systems, and an external specialist project manager was contracted to take it from conception to completion. Before launching the project he ensured that it was integrated with

BPMJ

11,4

372

the company’s strategic plans of moving from a supply chain, production focus to a customer-centric one. He involved many people from the business in a series of “to be” workshops that jointly defined the project’s vision. Together they identified two overarching objectives, which were clearly linked to the company’s strategy. The project manager also translated the project objectives into very specific deliverables, and in doing so helped to create the project’s business case. He maintained an extreme focus on delivering this business case throughout the project.

Wide business ownership was generated through workshops, communication events and “key users” (who provided the bridge between functional departments and the project team). Site managers were involved in defining the project scope and making decisions that impacted their sites, as well as leading the implementation at those locations. There was also good executive involvement, with half of the company’s executives sitting on the project steering team. The sponsor ensured that obstacles were cleared and that resources were made available when needed.

The best possible people were assigned full time to the project team, and they were all given challenging roles. Despite being collocated in rather shabby accommodation they had a strong team spirit. Each of them was promised a good job to move on to after the project, and a team financial bonus was promised upon successful delivery of the new system.

Some data preparation problems caused a slight delay in “go-live”, though the eventual cutover period was relatively smooth with minimal disruption to company operations. Despite some inevitable glitches in the first few months, many business processes have now been improved and the project has created the core platform upon which Company B can grow. It is widely considered to be successful, and all business benefits will be delivered.

The Project Alignment Model

The Project Alignment Model is shown in Figure 1. This has three main sections: environment; leadership; and management. These are discussed in detail in the following sub-sections.

Environment

The internal company and external business environments must be understood when setting up a project, and they must be monitored throughout the project’s life. Without this the project may struggle to remain relevant and aligned with the company’s current strategy

Business environment. The project timetable must be sympathetic to the external

business environment. Project A shows what can happen if a project fails to recognise and act upon changing business conditions. Company A’s management were being forced to close plants and cut costs in response to a collapsing market, but the project continued with its original purpose. As a result the project lost credibility with many stakeholders. In contrast, Company B’s business environment was reasonably stable and it was able to conduct a more substantial project.

Company strategy. Carnall (1999) explains that corporate strategy must be made

explicit and diffused throughout an organisation to allow people to plan and create change. The strategy should be simple and comprehensible, based on an identifiable core concept, with clear priorities and resource allocation. It may support super

Business process

management

373

ordinate goals focussed on organisational outcomes, which Collins and Porras (2000) describe as “big hairy audacious goals” – these are challenging goals and projects towards which a visionary company channels its efforts. An example is GE’s goal to be “number one or two in every market”. Project B’s teams frequently referred back to their company’s goals and validated that their proposed solutions would contribute to them.

Company-wide alignment. In their study of visionary, long-lasting companies,

Collins and Porras (2000) found that all their processes, practices, behaviours, etc. were aligned and mutually supporting. Well-known examples of companies with this level of alignment are IKEA and South West Airlines (Porter, 1996). If there is underlying alignment throughout a company, project alignment will be easier to achieve because project team members will be able to see how their activities contribute to the larger whole.

Culture of change. For many enterprises, project success or failure has little to do with the way the project itself is conducted, or the quality of the staff – much more important is the culture within the enterprise. An underlying culture of change acceptance will ease alignment of purpose for a project team, as they will be less distracted by the process of making the change and more able to concentrate on delivering the right change. A culture of change requires employees trained in change techniques and processes, trust, the acceptance of mistakes and organisational learning.

Change was rare and difficult for Company A and their plans had little cultural sensitivity – the timetable was set by how fast the technology could be implemented, rather than how quickly people could assimilate the changes. As a result senior management struggled to believe that the project would be successful and would not

Figure 1.

Project Alignment Model

BPMJ

11,4

374

support it. In contrast, Company B’s culture is very accepting of change – this inevitably made it easier for B’s people to align with and support the changes. Project plans must therefore be sensitive to the underlying culture of change.

Leadership

Kotter (1996) defines management as “a set of processes that keep a complicated system of people and technology running smoothly”, while leadership “defines what the future should look like, aligns people with that vision, and inspires them to make it happen despite the obstacles”. It is widely recognised that strong leadership is essential for effective change. For example, Hammer and Stanton (1995) say “if you proceed to re-engineer without the proper leadership, you are making a fatal mistake”. A change leader will be a role model enabling others to become aligned with a common course; “effective leadership requires an alignment of action with attitudes and purpose if the desired results are to be obtained” (Molden and Symes, 1999).

Create shared vision and purpose. A team purpose provides a unifying and

motivating reason for everything the team is trying to do. It is essential for alignment, and is the highest level in Molden and Symes’s (1999) Universal Alignment Model. They say that purpose is our reason for being, serving as a direction, a constant we can refer to over time. In a team, purpose needs to be clear and adopted by all. Dover (1999) adds that shared purpose provides employees with the information they need to judge whether a particular decision or action will enhance or detract from value creation, allowing them to focus their creative power. However, even well developed teams have different interpretations of purpose if the issue has not been centrally addressed, and people are left to toil in a context that they infer and create from what they see around them. Taborda (2000) believes that effective teams invest time and effort in exploring and agreeing on a purpose that gives them direction.

In large organisations there will be a purpose for the organisation and purposes for different functions, which must link together and feed one another (Molden and Symes, 1999). A change project therefore needs its own purpose. People must find meaning in this for themselves, and rather than a written document, it is the dialogue about purpose that engages people and provides the opportunity to attach meaning (Axelrod, 2000). The team’s purpose should be co-developed with the team itself, who should be allowed time to “throw it around” and digest it.

Molden and Symes (1999) say that a leadership behaviour essential for alignment is the creation of the shared purpose, helping others to understand what must be accomplished, why their work is worthwhile and how they can accomplish their goals. The case studies support this. Project B’s team members could clearly articulate their purpose, with a high degree of consistency between individuals. In contrast Project A’s team members demonstrated no consistent understanding.

Finally, alignment of purpose cannot be limited to the project team. For example, each of Project A’s stakeholder groups had a slightly different purpose for the project. While this will also have been true initially for Project B that project’s sponsor invested time to establish commonality of vision and purpose (whilst still recognising that each group may have had their own personal desires for the project).

Establish project identity. Molden and Symes (1999) believe that teams need

identities to work well, saying that this is the “sense of self, role or function – it is who we are”. They say that a weak identity makes it difficult for people to define

Business process

management

375

and connect with a purpose, thereby reducing the sense of belonging, leading to low commitment. Time spent with a team shaping, describing and trying on a new identity will be time well invested – this is where the strongest bonds between employees are made, and where high performing teams draw energy. Both case study projects attempted to create a project identity. Project B’s approach was particularly effective, making use of a project logo, a project launch event and regular social activities. This helped Project B to integrate team members with one another and build a feeling of camaraderie.

Share responsibility. Labovitz and Rosansky (1997) define distributed leadership as the presence of capable leadership at different levels of an organisation. They say that it is found at the edge of an aligned organisation, among people who are both empowered to act and knowledgeable about what must be done. Distributed leadership is the “glue” of alignment, and while the initial push must come from the top, alignment is only sustained when leadership at other levels is engaged. Applying this to a project environment, Kotter (1996) says that senior executives should focus on overall leadership tasks, while delegating responsibility for management and more detailed leadership as low as possible in the organisation.

There are many ways to achieve distributed leadership, including hiring people with a leadership disposition (Labovitz and Rosansky, 1997) and coaching to help people at all levels recognise that they are leaders (Piasecka, 2000). Kirkman and Rosen (2000) also suggest the establishment of coaching clinics or workshops to help leaders build the skills needed to empower teams.

Project governance responsibilities should be shared between several individuals. To illustrate, Project A’s first manager also assumed the roles of champion, owner, and to some extent sponsor. He was a zealot for his project, and hubris appeared to blind him from the stakeholder problems and the changing environment. The right project sponsor is also essential; this should be the most junior person that all the targets report to, as anyone else will struggle to make the changes happen. Again as an example, most of the proposed changes for Project A were targeted at people who did not report to the project sponsor and he in turn struggled to make changes in other departments.

Demonstrate commitment. Harrison (1999) suggests that many change efforts fail

because sponsors express, but do not reinforce, their commitment. Obeng (1994) adds that people “watch closely what you do and use this as a far more reliable guide to what you really mean”. Executives must therefore, “walk the talk” when trying to implement change. For example, half of Project B’s executive team made time to sit on the project steering team, and the sponsor in particular made sure that any obstacles were quickly removed. In contrast, most of the Project A’s executives avoided project involvement.

Adopt engaging style. Project managers often do not have the authority to instruct people in their duties, but they have to use a more subtle power base to achieve their purpose. This is more rooted in the shared commitment of a team rather than in directives. A project manager must therefore adopt an engaging leadership style to create and foster a team spirit and to enrol the commitment of people associated with the project. Goleman (2000) believes that good leaders demonstrate a balance of styles as the situation demands, and the following characteristics can help create an environment where people want to align with the leader’s purpose:

BPMJ

11,4

376

. showing passion (Hammer and Stanton, 1995);

. leading by example (Frohman and Pascarella, 1995);

. focusing on the institution, not oneself (Collins, 2001);

. being visible (Baker and Baker, 2000);

. motivating people (Carnall, 1999; Lidow, 1999);

. demonstrating respect for others (Molden and Symes, 1999);

. developing people (Schuitema, 1998);

. connecting with people individually (Zall, 2001; Schneider and Goldwasser, 1998);

. displaying and permitting emotions (Pendleburyet al., 1998; Molden and Symes, 1999); and

. trusting people (Duck, 1998; Nguyen-Huy, 2000; Lin, 1998).

Project B’s team had a strong team spirit. They looked after each other’s interests, worked hard together, and seemed to enjoy the shared project experience. This helped to pull them through difficult periods and they kept each other aligned, understanding that they succeeded or failed together. Creating a strong team spirit is the role of both formal and informal project leaders, but a group of individuals does not turn into a team overnight – Hammer and Stanton (1995) suggest that it usually takes at least a week of serious effort. They say that teams that take that time may lose a week up front, but they more than make up for it later on when their unity allows them to speed through problems and crises.

Management

Effective management is essential for alignment of business change initiatives, starting with processes to establish alignment at the start of the project and continuing with robust project management processes, systems and structures throughout the project’s life. This section of the model has therefore been split into two sub-sections: establish alignment and maintain alignment.

Establish alignment. Align project goals with strategy. A link between strategy and business plans is required to ensure that the right projects are initiated and that decisions are aligned to the strategy (Buttrick, 2000). Some common techniques to achieve this are the balanced scorecard (Kaplan and Norton, 1993, 1996), planning structure trees (Labovitz and Rosansky, 1997), and the logical techniques of Baccarini (1999) and Pendlebury et al. (1998). The manager of Project B linked the project’s objectives to company B’s strategic goals before going too far into the project. In contrast, Project A did not have a clear link to the company’s strategy. A clear path must be created from corporate strategy to project goals, and ultimately to team and individual objectives (Figure 2). All key project documentation must also present consistent messages.

Each of Project B’s promised benefits were linked to changes in the company’s business model, ensuring that every benefit would be delivered and that the project team did not waste effort on unnecessary changes. The project team were held accountable for delivering the agreed benefits, while incorporating the benefits into

Business process

management

377

departmental plans ensured that business owners benefited from the project. This helped to establish alignment between the project and the business owners.

Understand stakeholder expectations. Before a project is launched all stakeholders must have a common understanding of what needs to be done, what an acceptable outcome will look like, the project’s deliverables, and the approach that will be taken (Pitagorsky, 1998). Unfortunately Project A did not have this alignment and the team had to define their own objectives for the project during the process mapping exercise.

Create a business model of the changes. Labovitz and Rosansky’s (1997) horizontal alignment principle says that the customer’s voice should be a beacon and a driver for the way an organisation thinks, works, and is managed. Applying this to a change project demands that the project approach, processes and systems are appropriate to meet the stakeholder needs. The case studies confirm the vital role a business model can play in establishing alignment, by providing clarity on the intended changes to all participants as well as helping them select the most appropriate approach. In Project A’s “quick wins” phase a simple end-to-end process map acted as the business model, but for more complex projects a more detailed model may be appropriate.

Use good project management techniques. Good project management will ensure

that everyone knows what to do, and when to do it. It is therefore essential for alignment.

Clearly define scope. It is widely accepted that an effective team requires a clear charter (Govindarajan and Gupta, 2001; Hayes, 2000). Project B’s manager first created a succinct two-page project definition document with the intention of getting absolute clarity of purpose. Only when this was widely accepted did he create a full project registry, which was reviewed, discussed, and signed-off by all stakeholders before being presented at a formal launch event. Project B’s scope could then only be changed through a formal change control process. In contrast, Project A’s scope was poorly defined, not agreed, and grew during the project.

Adopt a stage-gate approach. A stage-gate methodology creates formal points at

which a project leader can assemble the team to assess alignment and confirm the project controls, roles and accountabilities before the next stage.

Co-create well-structured plan. Without a detailed, written plan shared with all

participants, a project is susceptible to differences between the expectations of project

Figure 2.

Alignment from strategy to individual objectives

BPMJ

11,4

378

team members and stakeholders (Smith and Mourier, 1999). Baker and Baker (2000) therefore said that the plan must be well communicated and that every team member needs a summary of the overall project goals, their role and task assignments and a list of who’s who on the project. A work breakdown structure also ensures that people know specifically what needs to be done (Buttrick, 2000).

The project team should build the plan together to encourage ownership (Pendleburyet al.1998). Baker and Baker (2000) add that the plan must be kept up to date, especially when changes are requested frequently, which is an indication of a lack of consensus regarding the original plan or some other political problem. They also suggest that the project manager should not start the project until all stakeholders have approved the plan.

Define individual roles and accountabilities. Clear, meaningful job roles help

employees to identify with a larger purpose and to align their personal values and goals (Dover, 1999). In contrast, a disordered organisational architecture can create tensions (D’Herbemont and Ce´sar, 1998). Each person in a project team must therefore fully comprehend what his/her role is in achieving the overall objective (Christian, 1993). Single point accountability helps achieve this by clearly defining what is expected of each person and eliminating overlaps (Buttrick, 2000). A visual organisation chart (Longnecker and Neubert, 2000) and a responsibility assignment matrix (PMBOK, 2000) can help to get this clarity, as will writing and agreeing formal role descriptions. Project B’s manager designed the team structure to minimise overlaps and interfaces. He also personally discussed individual objectives and responsibilities with key team members to confirm their understanding.

Encourage people to align. Ensure broad participation.Involving people is one of Pascale and Millemann’s (1997) keys to successful change. Involvement directs energy in support of the change and creates a feeling of ownership (Carnall, 1999). Without involvement employees may react by quietly distancing themselves from the change (Axelrod, 2000). Some effective ways to involve people include workshops, round tables and conferences.

According to Molden and Symes (1999) commitment to a purpose is strongest when people have been involved at the idea generation level or higher. Project teams should therefore be given the freedom to manage and direct themselves, including defining their own make-up and methods (Molden and Symes, 1999), and any blockers that reduce a team’s freedom to choose how it is organised and aligned should be removed (Pendleburyet al., 1998). These could include doing too much for the team, withholding responsibility and authority by poor delegation, and allocating insufficient time for team meetings.

Provide project team with means and ability.Misalignment could occur due to a lack of knowledge or experience (Molden and Symes, 1999), so a project team should be provided with the required skills and ability to perform its task. It must also understand why the task is necessary and how to perform it; only then can it be held accountable (Schuitema, 1998).

Establish supporting systems.Support systems directly or indirectly tell employees what to do, and Kotter (1996) says that they should make it in people’s best interests to implement the new vision. For example, Longnecker and Neubert (2000) suggest evaluating team members’ performance within the team with equal weight to their work outside of the project. Without this they may feel more personal gain through

Business process

management

379

cooperating with their functional manager’s plans when they conflict with team plans. Projects also often need their own reward and recognition systems, since those of the broader organisation may not be appropriate (PMBOK, 2000). As examples, personal objectives were aligned with project objectives and a team bonus was established for Project B.

The project should be career enhancing for team members, including finding them new roles in the organisation after the project. Individuals will also have their own personal goals for the project (e.g. to develop a new skill or to understand a new technology) – these should be recognised and planned for where possible.

Finally, the number of team members typically increases during a project’s later stages. Orientation processes may therefore be needed to align new team members with the purpose, although tight supervision and daily meetings were used instead for Project B’s small number of temporary team members.

Maintain alignment. A change project leader can make the best plans, but when the project starts he or she cannot predict exactly what will happen. The company’s strategy may change in response to the external business environment, the chosen solution may prove technically impossible to implement, or people may refuse to align with the intended change. Plans may also have to be changed in response to shifts in the political arena. Alignment is not something that can be achieved and then forgotten about, but it needs constant attention throughout the project’s lifecycle. The project leader must therefore take the company’s pulse on a regular basis, to see how its political health might be changing and to continually sense for misalignment.

Remain attuned to the external environment. Most project managers will look

downwards and inwards to the project to assess alignment, but a good manager will also look upwards and outwards to sense and respond to changes in the project’s environment (Figure 3). HMU (2001) emphasises business skills and commercial acumen over technical prowess when selecting a project manager.

Project managers must not get too emotionally attached to a project, or they may lose their objectivity and ability to make effective decisions. They must not be a zealot

Figure 3.

Sensing for misalignment

BPMJ

11,4

380

for the project’s purpose, but must be aware of issues, understanding of other people’s points of views, and be capable of finding balanced solutions. In fact, D’Herbemont and Ce´sar (1998) say that for a sensitive project the manager must, above all else, be a master of negotiation. Recognising this essential role, Company B contracted a professional project manager for their change project. In contrast Project A’s first manager was full of enthusiasm, but was inexperienced and did not know how to steer through the minefield of project politics.

Periodically assess and correct alignment. When a project is underway there is a

danger of losing focus on the business objectives that initiated it in the first place (Buttrick, 2000). People may slowly drift away from the purpose with time, and the project leader must rise above the day-to-day workload and conduct periodic reviews to maintain the focus on project goals throughout its life. Every project therefore needs both formal and informal monitoring and reporting activities (Baker and Baker, 2000). Techniques to review alignment include gathering project teams together frequently, meeting team members one-on-one, formal status reporting, employee surveys, management by walking around and bringing stakeholders into team meetings. Project B used daily meetings during the ramp-up to go-live and Project A’s team met around a whiteboard to keep their focus on key issues.

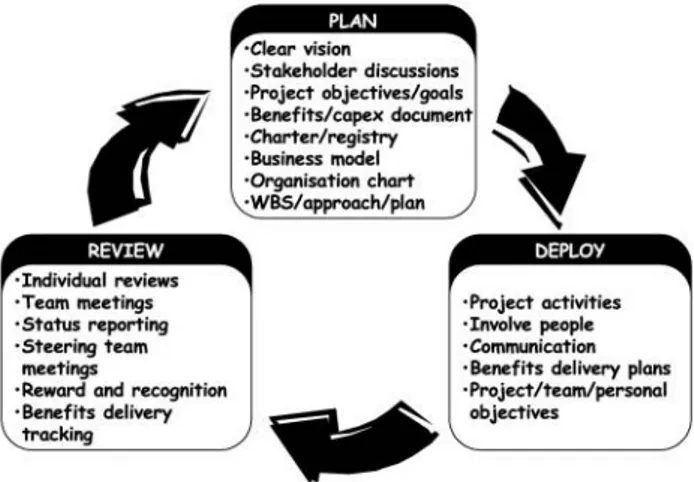

Labovitz and Rosansky (1997) recommend a Plan-Deploy-Review (PDR) cycle to maintain alignment in an organisation. A PDR cycle is also needed for change projects, and this is often achieved in practice through good project management techniques such as those shown in Figure 4. On finding misalignment a project leader can decide either to ignore it or to act upon it, while understanding that ignoring it can be dangerous in the long run. Table I describes some techniques to manage common reasons for misalignment.

Communicate effectively and honestly. Effective communication is essential for

people to know what they should be aligned with and how. For example, Obeng (1994) warns that people accept the parts of project briefings that look or sound familiar and ignore the bits that don’t fit with their previous experiences; as a result they may start a project without fully understanding what outcome their stakeholders want. Project A’s team were unaware of the problems their senior management had in accepting

Figure 4.

Project PDR process

Business process

management

381

the project – this created unnecessary frustration and made it difficult to re-engage the team at a later date. All communication should be:

. two-way (Oakland and Oakland, 2001);

. repeated (Kotter, 1996);

. honest (Schuitema, 1998; Collins, 2001); and

. personally relevant (Schneider and Goldwasser, 1998; McCune, 1999).

Discussion

The model we have presented is a pragmatic model. Our contribution has been to bring together many ideas from an amalgamation of disparate strands of literature, to illustrate their validity with a couple of case studies, and to structure them in an accessible way. We believe that the model can be useful both as a descriptive model and as a prescriptive model. Used descriptively, the model can help structure the analysis of change projects. As such it could be a useful research instrument. Academics could use the model to analyse change projects and structure their findings in a way that allows ready cross-case comparisons. Such an approach can, by categorisation, lead to a more detailed understanding of the factors affecting project alignment and successful change. Used prescriptively, the model can guide project managers in creating and maintaining project alignment.

Some of the details of the model may appear to be “obvious”, but that in no way diminishes the value of the model. Details might appear obvious to experts in the field, but this is not universally so (for example, they were not obvious to the managers in Case A). The model represents our best attempt to bring together, from the existing literature, a comprehensive “checklist” that we believe will have value.

However, there are a number of limitations to our work. The model has been validated by retrospective application to two case studies, where it was shown that

Reason for an individual’s misalignment Possible action

Don’t know what to be aligned with Use the business model to explain how the changes fit together and contribute to the company’s strategy/objectives

Review project documentation with the individual (e.g. charter/definition document, project plan, etc.) Ensure the person understands the project plan and how they personally fit into the overall project structure

Choose not to be aligned One-on-one discussion (listening as well as talking – there may be grounds for misalignment)

Try to convert them using project allies/influential people

Eventually remove the person from the project team if necessary

Prevented from being aligned Look for systems pulling them away (e.g. bonus based on functional rather than project activities) Ensure the person has time for project activities Ensure that their boss is supportive of project activities

Table I.

Techniques to address misalignment

BPMJ

11,4

382

a successful project adhered to many of the “recommendations” of the model, whereas an unsuccessful project contravened many of them. However, it has not been rigorously tested and many questions remain, for example:

Does a project need to adopt all these recommendations? If not, is there a priority list, i.e. are some recommendations more important than others? What would happen if only a sub-set is adopted?

These questions are outside the scope of this research and this paper. However, they indicate a potentially valuable area for further work.

Conclusion

Creating and maintaining alignment of purpose for change initiatives requires an understanding of the environment in which the change is being made, good leadership and effective project management. With companies facing increasingly dynamic business conditions, project managers must be increasingly business-aware and have more than just technical delivery skills. They need to be good leaders and capable of recognising and managing the political dimensions of a project. They should be capable of having strategic-level conversations and influencing company direction with sponsors one minute, then switching to the tactical level for delivery the next minute. To help these leaders maintain alignment in their projects, the key points from the Project Alignment Model are presented as a checklist in the Appendix.

References

Axelrod, R.H. (2000), Terms of Engagement: Changing the Way we Change Organisations, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco, CA.

Baccarini, D. (1999), “The logical framework for defining project success”,Project Management Journal, Vol. 30 No. 4, pp. 25-32.

Baker, S. and Baker, K. (2000),The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Project Management, Alpha Books, Indianapolis, IN.

Buttrick, R. (2000),Project Workout: Reap Rewards from All Your Business Projects, Pearson Education Ltd, London.

Carnall, C.A. (1999),Managing Change in Organisations, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Christian, P.H. (1993), “Project success or project failure: it’s up to you”,Industrial Management,

Vol. 35 No. 2.

Collins, J. (2001),Good to Great, Random House Business Books, London.

Collins, J.C. and Porras, J.I. (2000), Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies, Random House Business Books, London.

D’Herbemont, O. and Ce´sar, B. (1998), Managing Sensitive Projects, Macmillan Press Ltd, London.

Dover, K. (1999), “Avoiding empowerment traps”,Management Review, January pp. 51-5. Duck, J.D. (1998), “The art of balancing”,Harvard Business Review on Change, Harvard Business

School Press, Boston, MA.

Frohman, M. and Pascarella, P. (1995), “Don’t abdicate: teams’ effectiveness starts and ends at the top”,Information Week, 6 November.

Goleman, D. (2000), “Leadership that gets results”, Harvard Business Review, March-April pp. 78-90.

Business process

management

383

Govindarajan, V. and Gupta, A.K. (2001), “Building an effective global business team”, MIT Sloan Management Review, Summer pp. 63-71.

Hammer, M. and Stanton, S.A. (1995), The Re-engineering Revolution: A Handbook, Harper Collins, New York, NY.

Harrison, D. (1999), “Are you ready to be a change sponsor?”,Industrial Management, Vol. 41 No. 4, p. 6.

Hayes, D.S. (2000), “Evaluation and application of a project charter template to improve the project planning process”,Project Management Journal, Vol. 31 No. 1, p. 14.

HMU (2001), “Harvard management update; what you can learn from professional project managers”,Harvard Management Update, February.

Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (1993), “Putting the balanced scorecard to work”,Harvard Business Review, September-October pp. 134-9.

Kaplan, R.S. and Norton, D.P. (1996), “Using the balanced scorecard as a strategic management system”,Harvard Business Review, January-February pp. 75-85.

Kirkman, B.L. and Rosen, B. (2000), “Powering up teams”, Organizational Dynamics, Winter pp. 48-65.

Kotter, J.P. (1996),Leading Change, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA. Labovitz, G. and Rosansky, V. (1997),The Power of Alignment, Wiley, New York, NY. Lidow, D. (1999), “Duck alignment theory: going beyond classic project management theory to

maximise project success”,Project Management Journal, Vol. 30 No. 4, p. 8.

Lin, C.Y-Y. (1998), “The essence of empowerment: a conceptual model and a case illustration”,

Journal of Applied Management Studies, Vol. 7 No. 2, pp. 223-38.

Longnecker, C.O. and Neubert, M. (2000), “Barriers and gateways to management cooperation and teamwork”,Business Horizons, Vol. 43 No. 5, p. 37.

McCune, J.C. (1999), “The change makers”,Management Review, Vol. 88 No. 5, pp. 16-22. Molden, D. and Symes, J. (1999), Realigning for Change, Financial Times Professional Ltd,

London.

Nguyen-Huy, Q. (2000), “Do humanistic values matter?”,Academy of Management Proceedings. Oakland, S. and Oakland, J.S. (2001), “Current people management activities in world-class

organisations”,Total Quality Management, Vol. 12 No. 6, pp. 773-88.

Obeng, E. (1994),All Change! The Project Leader’s Secret Handbook, Pitman Publishing, London. Pascale, R. and Millemann, M. (1997), “Changing the way we change”,Harvard Business Review,

Vol. 75 No. 6, pp. 126-139.

Pendlebury, J., Grouard, B. and Meston, F. (1998), The Ten Keys to Successful Change Management, Wiley, Chichester.

Piasecka, A. (2000), “Not ‘Leadership’ but ‘leadership’”,Industrial and Commercial Training, Vol. 32 No. 7, pp. 253-5.

Pitagorsky, G. (1998), “The project manager/functional manager partnership”, Project Management Journal, December, pp. 7-16.

PMBOK (2000),A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Project Management Institute, Newton Square, PA.

Porter, M.E. (1996), “What is strategy?”,Harvard Business Review, Vol. 74 No. 6, p. 61. Schneider, D.M. and Goldwasser, C. (1998), “Be a model leader of change”,Management Review,

Vol. 3, p. 41.

BPMJ

11,4

384

Schuitema, E. (1998),Leadership: The Care and Growth Model, Ampersand Press, Kenilworth. Smith, M.E. and Mourier, P. (1999), “Implementation: key to organisational change”,Strategy and

Leadership, Vol. 27 No. 6, p. 37.

Spiker, B.K. (1995), “We have met the enemy”,Journal of Business Strategy, Vol. 16 No. 2. Strebel, P. (1998), “Why do employees resist change?”,Harvard Business Review on Change,

Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Taborda, C. (2000), “Leadership, teamwork, and empowerment: future management trends”,Cost Engineering, Vol. 42 No. 10, pp. 41-4.

Zall, M. (2001), “Employees or partners?”,Strategic Finance, April, pp. 62-5.

Further reading

Hayes, R.H. (1985), “Strategic planning – forward in reverse”, Harvard Business Review, November-December, pp. 111-19.

Appendix

Environment

Business environment Understand the external business environment Ensure that project plans are sensitive to the external environment

Company strategy Understand the company’s strategic plans

Ensure the strategy is well communicated to the project team Understand and communicate company-wide superordinate goals or vision

Company-wide alignment Build on underlying alignment in the organisation Culture of change Be sensitive to the ability of the organisation to change

Assess whether:

Employees are familiar with change techniques and processes

The organisation learns from its experiences Risk taking is encouraged

Trust and respect are commonplace Leadership

Create shared vision and purpose Co-create the project purpose with all stakeholders Ensure purpose defines what, why, how and when Establish a “case for meaning”

Create a vision of the future

Ensure purpose is supported by all stakeholders Establish project identity Establish clear reason for the team’s existence

Hold a launch event

Bring the project alive through shared values, behaviours, attitudes and beliefs

Make the project attractive with a positive image Share responsibility Form a strong guiding coalition of key stakeholders

Empower the project team and hold them accountable Ensure individual responsibilities are understood

Separate the roles of manager, sponsor, champion and owner Project sponsor should be the most junior person to whom all change targets report

(continued)

Table AI.

Guidelines for achieving and maintaining project alignment

Business process

management

385

Demonstrate commitment Senior managers and executives to “walk the talk” Espouse new behaviours

Understand and discuss the changes with employees Participate in project events

Adopt engaging style Show passion Lead by example

Focus on the institution, not oneself Be visible

Motivate people

Demonstrate respect for others Develop people

Connect with people individually Display and permit emotions Trust people

Management – establish alignment

Align project goals with strategy Establish clear link with strategy before launching the project Align team and individual goals with company goals Build project goals into business plans

Ensure project documentation is mutually supporting Understand stakeholder expectations Devote adequate time to getting alignment of purpose and

vision at the start of the project

Use stakeholders’ needs to determine the project approach, processes and systems

Create a business model of the changes

Use a business model to provide clarity on the intended changes to all participants

Use the business model to link benefits and deliverables Clearly define scope Use a project charter to get alignment

Agree scope with all stakeholders early on Adopt a stage-gate approach Assess alignment at the start of each project stage Co-create well-structured plan Encourage the project team to create the plan together

Create a clear work breakdown structure

Ensure the plan is well communicated and understood Keep the plan up to date as the project progresses

Do not start the project until all stakeholders have approved the plan

Define individual roles and accountabilities

Ensure each person understands his/her role in achieving the overall objective

Clearly define the project organisation Establish single point accountability

Ensure broad participation Encourage project teams to define their own approach, make up and methods

Remove blockers that reduce each team’s freedom to chose how it is organised and aligned

Use workshops, walkthroughs and round table discussions Provide project team with

means and ability

Assign the best possible people to project roles (ideally full time)

Provide the team with the means and ability to be able to perform their task

Help the team to understand why their task is necessary

Staff appropriately, and allow time for project activities

Collocate project team (where possible)

(continued)

Table AI.

BPMJ

11,4

386

Establish supporting systems Establish HR systems that encourage team members to deliver the project objectives, e.g.

Evaluate team members performance within the team with equal weight to their work outside of the project

Establish project reward and recognition system Ensure project is career-enhancing for team members, including finding them new roles upon completion

Establish an orientation process or close supervision for new or temporary team members

Management – maintain alignment Communicate effectively and honestly

Ensure communication is Two-way

Repeated Honest

Personally relevant Periodically assess and maintain

alignment

Establish informal and formal monitoring and reporting mechanisms, e.g.

Frequent team meetings Meeting team members one-one Formal status reporting Employee surveys

Identify and manage politics and power issues Bring stakeholders into team meetings Manage by walking around

Carefully chose which battles to fight at the right time Remain attuned to the external

environment

Look upwards and outwards to the business, as well as downwards and inwards to the project

Identify and respond to changes in the organisation’s power balance, business environment and strategic direction

Do not get too emotionally attached to the project Table AI.

Business process

management

387

This article has been cited by:

1. Youseef Alotaibi. 2016. Business process modelling challenges and solutions: a literature review. Journal of Intelligent Manufacturing27:4, 701-723. [CrossRef]

2. Gopal Das Department of Marketing, Indian Institute of Management Rohtak, Rohtak, India Srabanti Mukherjee VGSoM, IIT Kharagpur, Kharagpur, India . 2016. A measure of medical tourism destination brand equity. International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing10:1, 104-128. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

3. Youseef Alotaibi, Fei Liu. 2016. Survey of business process management: challenges and solutions.

Enterprise Information Systems 1-35. [CrossRef]

4. Diana Chronéer, Fredrik Backlund. 2015. A Holistic View on Learning in Project-Based Organizations.

Project Management Journal46:3, 61-74. [CrossRef]

5. Arijit Sikdar Faculty of Business & Management, University of Wollongong in Dubai, Dubai, UAE Jayashree Payyazhi Faculty of Business & Management, University of Wollongong in Dubai, Dubai, UAE . 2014. A process model of managing organizational change during business process redesign. Business Process Management Journal20:6, 971-998. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

6. Integrated change control 319-328. [CrossRef]

7. Mikko Uoti, Kim Jansson, Iris Karvonen, Martin Ollus, Sergio GusmeroliProject Alignment: A Configurable Model and Tool for Managing Critical Shared Processes in Collaborative Projects 87-96. [CrossRef]

8. Martin Ollus, Kim Jansson, Iris Karvonen, Mikko Uoti, Heli Riikonen. 2011. Supporting collaborative project management. Production Planning & Control22:5-6, 538-553. [CrossRef]

9. Jan vom BrockeInstitute of Information Systems, University of Liechtenstein, Vaduz, Principality of Liechtenstein Theresa SinnlInstitute of Information Systems, University of Liechtenstein, Vaduz, Principality of Liechtenstein. 2011. Culture in business process management: a literature review. Business Process Management Journal17:2, 357-378. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

10. Kim Jansson, Iris Karvonen, Martin Ollus, Mikko Uoti. 2011. Collaborative Project Alignment. IFAC Proceedings Volumes44:1, 11955-11960. [CrossRef]

11. Z Irani. 2010. Investment evaluation within project management: an information systems perspective.

Journal of the Operational Research Society61:6, 917-928. [CrossRef]

12. Rute GonçalvesBusiness process management as continuous improvement in business process 67-74. [CrossRef]

13. Emad M. KamhawiProduction Efficiency Institute, Zagazig University, Egypt. 2008. Determinants of Bahraini managers' acceptance of business process reengineering. Business Process Management Journal

14:2, 166-187. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

14. Melodena Stephens BalakrishnanUniversity of Wollongong in Dubai, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. 2008. Dubai – a star in the east. Journal of Place Management and Development 1:1, 62-91. [Abstract] [Full Text] [PDF]

15. Ralph Foorthuis, Sjaak Brinkkemper, Rik BosAn Artifact Model for Projects Conforming to Enterprise Architecture 30-46. [CrossRef]

16. Cam Caldwell, Howard White, R. H. Red Owl. 2007. The Case for Creating a DBA Program – A Virtue-based Opportunity for Universities. Journal of Academic Ethics5:2-4, 179-188. [CrossRef]

17. Kijpokin KasemsapThe Role of Business Process Reengineering in the Modern Business World 87-114. [CrossRef]

18. Kijpokin KasemsapThe Role of Business Process Reengineering in the Modern Business World 1802-1829. [CrossRef]

19. Luca RomanoPortfolio Management as a Step into the Future 1-38. [CrossRef]