Renal function, plasma homocysteine and carotid atherosclerosis

in elderly people

Catharine R. Gale

a,*, Hazel Ashurst

b, Nirree J. Phillips

a, Stuart J. Moat

c,

James R. Bonham

d, Christopher N. Martyn

aaMRC En6ironmental Epidemiology Unit,Uni6ersity of Southampton,Southampton General Hospital,Southampton,UK bDirectorate of Medical Physics and Clinical Technology,Northern General Hospital,Sheffield,UK

cDi6ision of Child Health,Uni6ersity of Sheffield,Sheffield Children’s Hospital,Sheffield,UK dDepartment of Chemical Pathology and Neonatal Screening,Sheffield Children’s Hospital,Sheffield,UK

Received 1 October 1999; received in revised form 22 February 2000; accepted 3 March 2000

Abstract

Although epidemiological studies suggest that people with minor impairment of renal function are at higher risk of stroke and coronary heart disease, the mechanisms underlying this relation are unclear. One explanation may lie with observations that deterioration in renal function is accompanied by elevations in plasma homocysteine concentrations. There is evidence that moderate hyperhomocysteinemia may play a causal role in atherosclerotic disease. We investigated the relations between renal function, plasma homocysteine and atherosclerosis of the carotid arteries in 128 men and women aged 69 – 74 years. Renal function was assessed by creatinine clearance and serum creatinine. Duplex ultrasonography was used to quantify the degree of stenosis in the extracranial carotid arteries. Severity of carotid atherosclerosis was greatest in men and women with the poorest renal function, whether measured by creatinine clearance or serum creatinine. After adjustment for plasma homocysteine, pulse pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors, the odds ratio for having carotid stenosis \30% was 4.3 (95% CI 1.4 – 12.9) in those whose creatinine clearance rate was 55 ml/min or less compared with those whose creatinine clearance rate was \73 ml/min. Even small decrements in renal function were associated with increased risk; people whose creatinine clearance rate was between 56 and 73 ml/min had an odds ratio of 3.8 (95% CI 1.2 – 11.9). Plasma homocysteine concentrations were significantly higher in people with poorer renal function, but they did not explain the associations we found between carotid atherosclerosis and creatinine clearance or serum creatinine. © 2001 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Carotid atherosclerois; Homocysteine; Renal function; Creatinine clearance; Elderly people

www.elsevier.com/locate/atherosclerosis

1. Introduction

Several epidemiological studies have shown associa-tions between raised concentraassocia-tions of serum creatinine within the normal range and subsequent mortality from stroke and coronary heart disease [1 – 4]. The mecha-nism underlying this link between minor impairment of renal function and cardiovascular risk is unclear. Al-though hypertension is an important predictor of de-cline in renal function [5,6], the associations described above persisted after adjustment for baseline blood

pressure and were seen in both normotensive and hy-pertensive subjects [1 – 4].

One explanation may lie with the role that renal function plays in regulating plasma concentrations of homocysteine [7]. In recent years, there has been grow-ing interest in the possibility that moderate hyperhomo-cysteinemia may be implicated in the aetiology of cardiovascular disease [8]. Plasma homocysteine con-centrations have been shown to rise as renal function deteriorates [9,10], and it has been suggested that this may help to explain the increased risk of atherosclerosis seen in patients with kidney failure or diabetic nephropathy [11,12]. Whether increases in homocys-teine might also be associated with greater severity of atherosclerosis in people with only minor deterioration of renal function is unknown.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +44-(0)23 80777624; fax: +44-(0) 23 80704021.

E-mail address:[email protected] (C.R. Gale).

Duplex ultrasonography is a non-invasive, specific and sensitive technique for detecting atherosclerosis in the extra-cranial carotid arteries. We used this method to assess the prevalence and extent of disease in a group of elderly men and women. Our aim was to investigate the relation between kidney function, as assessed by serum creatinine and creatinine clearance, plasma ho-mocysteine and carotid atherosclerosis.

2. Methods

Over the last few years, the MRC Environmental Epidemiology Unit has been carrying out a series of studies on cohorts of men and women born in the Jessop Hospital for Women, Sheffield. These people were traced by the National Health Service Central Register and those still living in the city were invited to take part in research into the processes by which size at birth influences adult disease [13]. In 1993 – 1994, we studied a group of 322 men and women born between 1922 and 1926, as has been described previously [14]. Recently, we took the opportunity to explore the rela-tion between kidney funcrela-tion, plasma homocysteine and carotid atherosclerosis in this cohort.

After obtaining permission from their general practi-tioners, we were able to write to 288 (89%) of the 322 men and women who had taken part in earlier research, asking whether they would be willing to be interviewed at home. A total of 212 (74%) agreed and were inter-viewed by a fieldworker. The fieldworker administered the Rose/WHO Cardiovascular Questionnaire and en-quired about history of cardiovascular disease, smoking habits, current medication, and the most recent occupa-tion of the participant or her husband. Height and weight were measured. Blood pressure was measured twice in the right arm with an automated recorder while the participant was seated. The cuff was removed and replaced between measurements, and a mean blood pressure measurement was calculated. The participant’s social class was derived from their own or, for women, the husband’s most recent occupation. Reports of a history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack were confirmed from the general practitioners’ records.

After the interview, the participants were invited to attend a clinic at the Northern General Hospital, She-ffield. One hundred and forty six agreed to attend. They were also asked to collect their urine 24 h prior to their clinic attendance. One hundred and twenty eight agreed (60% of those interviewed) to do so. At the clinic, fasting venous blood samples were taken for measure-ment of plasma concentrations of homocysteine and serum concentrations of creatinine, glucose, total cholesterol, high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. As ho-mozygosity for the C677T mutation in the enzyme

methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) can be a cause of elevated homocysteine concentrations [15], a further blood sample was taken to assess MTHFR genotype. A 12-lead electrocardiogram was recorded. Participants underwent a colour duplex ultrasono-graphic examination of the carotid arteries with an Advanced Technology Laboratories HDI3000 high-res-olution, colour-flow Doppler real-time scanner equipped with a 10 – 5 MHz linear array probe. The ultrasonographer examined the common, internal and external carotid arteries and the carotid bifurcation, with longitudinal and transverse scans, and estimated the maximum degree of stenosis, as a percentage of lumen diameter loss on each side. Four categories were defined; no plaques, up to 30% stenosis, 31 – 50% steno-sis and more than 50% stenosteno-sis. Total plasma homocys-teine was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with fluorescence detection as described by Spaapen et al. [16]. Serum and urine creatinine concentrations were measured using an auto-mated clinical chemistry system (Dade Behring Dimen-sion XL), which employs a modification of the kinetic Jaffe reaction [17]. MTHFR genotype was determined by PCR amplification and subsequent digestion by the restriction enzyme HinfI; the resulting two fragments were then resolved by gel electrophoresis [15]. The study was approved by the North Sheffield Local Re-search Ethics Committee and all participants gave writ-ten informed consent.

We used ANOVA, the x2-test and logistic regression to examine the relation between kidney function, as assessed by serum creatinine and creatinine clearance, plasma homocysteine and degree of carotid atherosclerosis.

The distributions of plasma homocysteine, plasma glucose, serum creatinine and serum HDL and LDL cholesterol were skewed and were therefore log-trans-formed. We defined the degree of carotid stenosis as the maximum percentage of stenosis observed in either the right or left carotid arteries, by means of the categories described above. Creatinine clearance was calculated from creatinine excretion in a 24-h urine collection and a single measure of serum creatinine.

3. Results

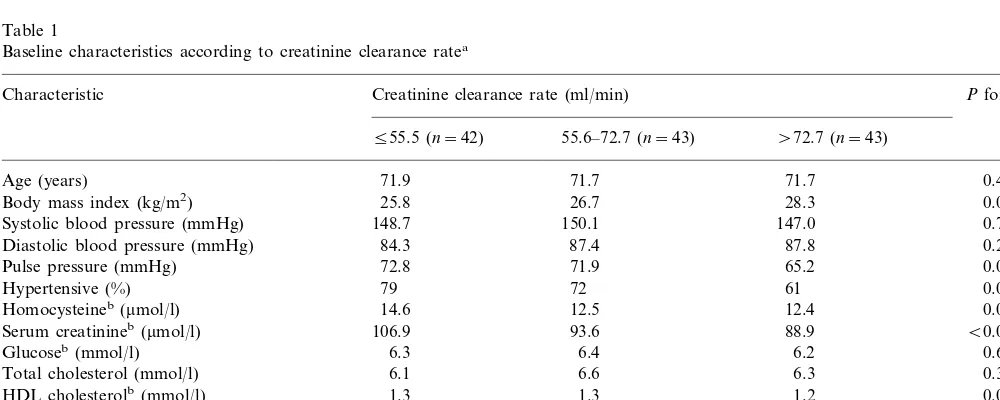

distribution. They also had a lower body mass index and lower serum concentrations of LDL cholesterol. Although there were no statistically significant trends between creatinine clearance rates and either systolic or diastolic blood pressure, people with lower creatinine clearance rates tended to have a higher pulse pressure and a higher prevalence of hypertension (systolic pres-sure of ]160 mm Hg or current treatment with antihy-pertensive drugs). In total, 27 (21%) participants had a creatinine clearance rate of 50 ml/min or less, a level generally regarded as indicating impaired renal function.

Ultrasound scans showed that 20 (16%) of these elderly men and women had carotid arteries that were free of atherosclerotic plaque. Fifty seven (44%) partic-ipants had plaque that caused a minor degree of steno-sis (530% reduction in lumen diameter). Only 10 (8%) had stenosis greater than 50%. Carotid atherosclerosis occurred more frequently and with greater severity in men than in women (P=0.005). Thirteen (10%) partic-ipants had a confirmed history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack and 35 (28%) had evidence of coro-nary heart disease, as defined by electrocardiography (Minnesota codes 1.1 – 1 – 2), by their medical history (coronary artery bypass grafting or coronary angio-plasty), or by a positive Rose/WHO chest-pain ques-tionnaire. Both these groups had more severe carotid stenosis than the rest of the study population (P=

0.002 and 0.023, respectively).

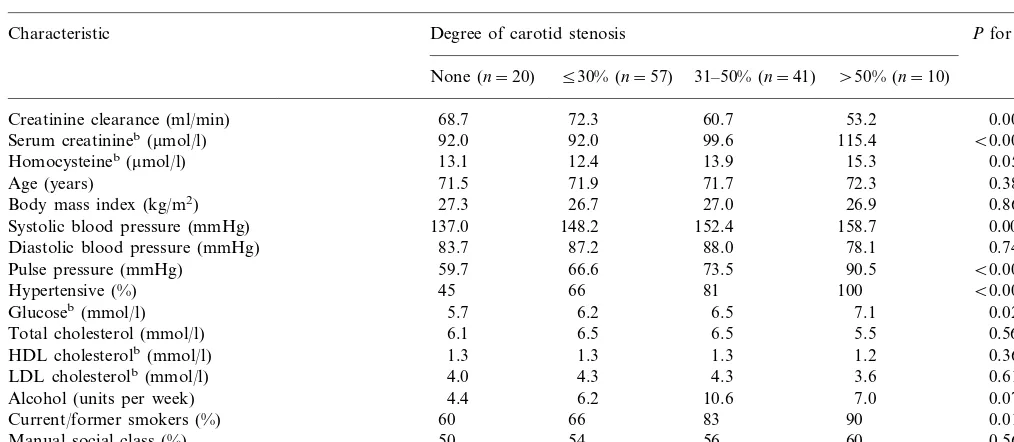

Participants in the four categories of carotid stenosis differed significantly in kidney function, whether as-sessed by creatinine clearance rate or serum creatinine (Table 2). Creatinine clearance tended to be highest in people with little or no narrowing of the carotid arteries

and it fell as the degree of stenosis increased. Mean serum creatinine rose as the degree of stenosis in-creased. Men and women with more severe stenosis had, on average, higher fasting concentrations of plasma homocysteine and glucose. They were also more likely to be current or former smokers. Mean systolic blood pressure, pulse pressure and the prevalence of hypertension were directly proportional to the severity of carotid stenosis. Alcohol intake tended to be higher in people with more severe stenosis, though this trend was of borderline statistical significance. There were no statistically significant relations between the degree of carotid stenosis and age, body mass index, social class, or serum concentrations of total, HDL or LDL choles-terol. Despite the association between carotid stenosis and plasma homocysteine concentrations, we found no relation between the degree of stenosis and the C677T mutation of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR).

The odds ratio for having carotid stenosis greater than 30% was increased among people with evidence of poorer kidney function. Men and women whose crea-tinine clearance rate was 55.5 ml/min or less had an odds ratio for stenosis of 4.7 (95% CI 1.7 – 12.9), com-pared to those whose creatinine clearance was over 72.7 ml/min. The odds ratio for stenosis among people whose serum creatinine was over 102 mmol/l was 3.8 (95% CI 1.4 – 10.3), compared to those whose serum creatinine was 56mmol/l or less. Adjustment for plasma homocysteine concentrations had little effect on these risk estimates (Table 3). They remained statistically significant after further adjustment for pulse pressure, plasma glucose, smoking status and alcohol intake (similar results were obtained when systolic blood

pres-Table 1

Baseline characteristics according to creatinine clearance ratea

Creatinine clearance rate (ml/min)

Characteristic Pfor trend

555.5 (n=42) 55.6–72.7 (n=43) \72.7 (n=43)

71.9

Age (years) 71.7 71.7 0.442

0.006

Body mass index (kg/m2) 25.8 26.7 28.3

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 148.7 150.1 147.0 0.707

0.240

84.3 87.8

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) 87.4

65.2

72.8 71.9 0.088

Pulse pressure (mmHg)

72 61

Hypertensive (%) 79 0.069

0.010 12.4

12.5 Homocysteineb(mmol/l) 14.6

106.9 93.6 B0.001

Serum creatinineb(mmol/l) 88.9

6.2 0.682

Glucoseb(mmol/l) 6.3 6.4

6.3 0.335

Total cholesterol (mmol/l) 6.1 6.6

0.053 1.2

1.3 HDL cholesterolb(mmol/l) 1.3

0.021

3.8 4.4 4.3

LDL cholesterolb(mmol/l)

8.7 6.5

Alcohol (units per week) 7.1 0.505

77

Current/former smokers (%) 69 72 0.758

Manual social class (%) 52 49 61 0.453

Table 2

Creatinine clearance, serum creatinine, plasma homocysteine and other risk factors according to degree of carotid stenosisa

Pfor trend Characteristic Degree of carotid stenosis

530% (n=57) 31–50% (n=41)

None (n=20) \50% (n=10)

72.3 60.7

Creatinine clearance (ml/min) 68.7 53.2 0.002

92.0 99.6

92.0 115.4

Serum creatinineb(mmol/l) B0.001

13.1

Homocysteineb(mmol/l) 12.4 13.9 15.3 0.050

71.5

Age (years) 71.9 71.7 72.3 0.382

26.7 27.0

27.3 26.9

Body mass index (kg/m2) 0.863

137.0

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 148.2 152.4 158.7 0.003

87.2 88.0

83.7 78.1

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) 0.748

59.7

Pulse pressure (mmHg) 66.6 73.5 90.5 B0.001

45

Hypertensive (%) 66 81 100 B0.001

6.2 6.5

5.7 7.1

Glucoseb(mmol/l) 0.022

6.1

Total cholesterol (mmol/l) 6.5 6.5 5.5 0.568

1.3 1.3

1.3 1.2

HDL cholesterolb(mmol/l) 0.367

4.3 4.3

LDL cholesterolb(mmol/l) 4.0 3.6 0.617

6.2 10.6

4.4 7.0

Alcohol (units per week) 0.074

66

Current/former smokers (%) 60 83 90 0.014

54 56

50 60

Manual social class (%) 0.561

20

Homozygous for MTHFR C677T mutation (%) 13 17 10 0.735

aValues are sex-adjusted means unless stated otherwise. bGeometric means.

Table 3

Odds ratios for carotid stenosis greater than 30% according to measures of renal function

Odds ratio (95% CI) Number

Adjusted for sex Adjusted for sex and plasma Adjusted for sex, plasma homocysteine and other risk factorsa

homocysteine

Creatinine clearance(ml/min)

42

555.5 4.7 (1.7–12.9) 4.3 (1.6–11.6) 4.3 (1.4–12.9) 43

55.6–72.7 3.8 (1.4–10.0) 4.2 (1.6–10.5) 3.8 (1.2–11.9)

1.0 1.0

43 1.0

\72.7

Pfor trend Pfor trend=0.002 Pfor trend=0.009

B0.001

Serum creatinine(mmol/l)

1.0 1.0 1.0

556 43

2.0 (0.8–5.4) 1.8 (0.7–4.7)

43 1.7 (0.5–5.2)

57–102

\102 42 3.8 (1.4–10.3) 3.1 (1.1–8.7) 3.5 (1.1–11.5)

Pfor Pfor trend=0.007 Pfor trend=0.008 trend=0.002

aMultivariate model also includes pulse pressure, plasma glucose, smoking status and alcohol intake.

sure and hypertension were substituted in the models for pulse pressure).

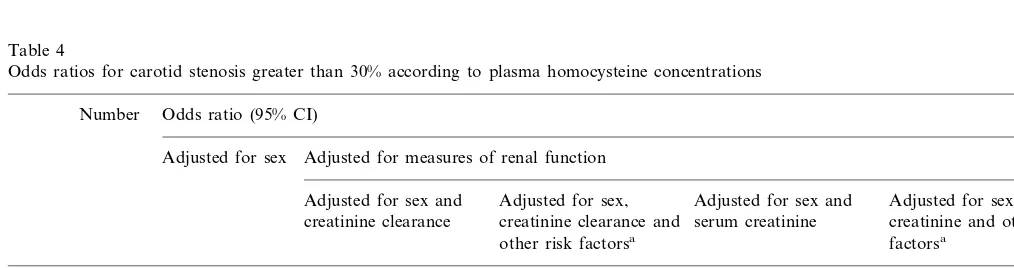

Men and women whose concentrations of plasma homocysteine were above the median (13mmol/l) had a slightly increased risk of having carotid stenosis greater than 30% (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.0 – 2.2). After adjustment for creatinine clearance and other risk factors, the association between plasma homocysteine and carotid stenosis was of borderline statistical significance but the odds ratios were little changed (Table 4). Inclusion of serum creatinine and other risk factors in the multivari-ate models weakened the association and it ceased to be statistically significant.

4. Discussion

smokers and in people with raised systolic blood pres-sure or pulse prespres-sure or high fasting plasma glucose concentrations, but the relation between carotid steno-sis and measures of kidney function remained statisti-cally significant after adjustment for these risk factors in multivariate analysis.

Our community-based study concerns 128 men and women who agreed to attend a hospital clinic and provide a 24-h urine collection. Although the study sample is small in epidemiological terms, the variation we found in the prevalence and severity of atheroscle-rotic disease is similar to that seen in other studies of elderly people [18].

There is considerable evidence that patients with chronic renal failure have above average rates of stroke and coronary heart disease [19 – 21]. Ultrasound studies have confirmed that such people have a higher preva-lence of atherosclerosis than healthy controls [22]. The results of the present study suggest that even minor decrements in renal function may be associated with an increased likelihood of atherosclerotic disease. Most of our elderly participants had creatinine clearance rates that were within the normal range, but there was still a 3-fold difference in risk of carotid stenosis between those whose clearance rates were between 56 and 73 ml/min and those with rates above 73 ml/min. A similar association has recently been reported from a study of 88 elderly people, though here renal function was as-sessed by serum creatinine levels alone [23].

In large-scale cross-sectional studies in Framingham [18], Rotterdam [24], and Perth [25] and in the Atherosclerosis Risk in the Community Study (ARIC) [26], people with raised plasma homocysteine concen-trations had an increased risk of carotid atherosclerosis. Among our 128 elderly participants, those with higher homocysteine levels had a slightly elevated risk, but this was of borderline statistical significance after adjust-ment of other cardiovascular risk factors. Although

deterioration in renal function is known to be a cause of raised homocysteine concentrations, [9,10,27] it is possible that raised homocysteine could contribute to impaired renal performance through an effect on atherogenesis in the renal arteries. However, the fact that the strength of the associations found between carotid stenosis and measures of renal function was little changed when plasma homocysteine was added to the models suggests that in these data homocysteine is neither a confounder of the association nor a likely cause of atherosclerosis.

The lack of association found here between atherosclerotic disease and the C677T MTHFR muta-tion, a genetic determinant of hyperhomocysteinemia, reflects the results of several other studies [25,28 – 30]. Although there is evidence that homozygosity for this mutation increases cardiovascular risk [31], the incon-sistency of the findings has lead to increased uncer-tainty about the existence of a causal relation between hyperhomocysteinemia and cardiovascular disease [8]. Hypertension is an obvious potential confounder of the relation between renal function and atherosclerotic disease, but the associations found here persisted after adjustment for current blood pressure or treatment with anti-hypertensive drugs. It is possible, of course, that the loss of renal function in these elderly people is in part a reflection of the duration or severity of hypertension, but we had insufficient data to assess this. The finding that atherosclerosis of the carotid arteries is more severe in individuals with minor impairment of renal function is consistent with the higher risk of stroke seen in such people [1,32]. Elevated pulse pres-sure seemed to play some part in this increased risk of atheroma, but there was no evidence that raised con-centrations of plasma homocysteine played a causal role. Whatever the mechanism, small decrements in renal function appear to be an important indicator of the severity of atherosclerotic disease in elderly people.

Table 4

Odds ratios for carotid stenosis greater than 30% according to plasma homocysteine concentrations

Number Odds ratio (95% CI)

Adjusted for measures of renal function Adjusted for sex

Adjusted for sex and Adjusted for sex, Adjusted for sex and Adjusted for sex, serum creatinine clearance and

creatinine clearance serum creatinine creatinine and other risk factorsa

other risk factorsa

Homocysteine(mmol/l)

1.0 1.0

1.0 1.0

75 1.0

513

53 1.5 (1.0–2.2) 1.5 (1.0–2.3)

]14 1.5 (1.0–2.5) 1.2 (0.8–1.9) 1.4 (0.9–2.1)

P=0.045 P=0.061 P=0.073 P=0.314 P=0.146

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants for their time; Kate Ellis, Karen Cusick and Elaine Langley who did the field-work; and Anne Grant for data processing. The study was funded by the Medical Research Council, the Gatsby Charitable Foundation and the Stroke Association.

References

[1] Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Perry IJ. Serum creatinine con-centration and risk of cardiovascular disease — a possible marker for increased risk of stroke. Stroke 1997;28:557 – 63. [2] Matts JP, Karnegis JN, Campos CT, Fitch LL, Johnson JW,

Buchwald H. Serum creatinine as an independent predictor of coronary heart disease mortality in normotensive survivors of myocardial infarction. J Fam Pract 1993;36:497 – 503.

[3] Damsgaard EM, Froland A, Jorgensen OD, Mogensen CE. Microalbuminuria as predictor of increased mortality in elderly people. Br Med J 1990;300:297 – 300.

[4] Shulman NB, Ford CE, Hall WD, Blaufox MD, Simon D, Langford HG, Schneider KA. Prognostic value of serum crea-tinine and effect of treatment of hypertension on renal function: results from the hypertension detection and follow-up program. Hypertension 1989;13(Suppl I):80 – 93.

[5] Rosansky SJ, Hoover DR, Kig L, Gibson J. The association of blood pressure levels and change in renal function in hyperten-sive and non-hypertensive subjects. Arch Intern Med 1990;150:2073 – 6.

[6] Walker G, Neaton J, Cutler JA, Neuwirth R, Cohen JD. Renal function change in hypertensive members of the multiple risk factor intervention trial: racial and treatment effects. J Am Med Assoc 1992;268:3085 – 91.

[7] Bostom A, Brosnan JT, Hall B, Nadeau MR, Selhub J. Net uptake of plasma homocysteine by the rat kidney in vivo. Atherosclerosis 1995;116:59 – 62.

[8] Cattaneo M. Hyperhomocysteinemia, atherosclerosis and throm-bosis. Thromb Haemost 1999;81:165 – 76.

[9] Norlund L, Grubb A, Fex G, Leksell H, Nilsson JE, Schenck H, Hultberg B. The increase in plasma homocysteine concentrations with age is partly due to the deterioration of renal function as determined by plasma cystatin C. Clin Chem Lab Med 1998;36:175 – 8.

[10] Arnadottir M, Hultberg B, Nilsson-Ehle P, Thysell H. The effect of reduced glomerular filtration rate on plasma total homocys-teine. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 1996;56:41 – 6.

[11] Chico A, Perez A, Cordoba A. Plasma homocysteine is related to albumin excretion rate in patients with diabetes mellitus: a new link between diabetic nephropathy and cardiovascular dis-ease? Diabetologia 1998;41:684 – 93.

[12] Chauveau P, Chadefaux B, Coude M, Aupetit J, Hannedouche T, Kamoun P, Jungers P. Hyperhomocysteinemia, a risk factor for atherosclerosis in chronic uremic patients. Kidney Int 1993;43:S72 – 7.

[13] Barker DJP. Mothers, Babies, and Disease in Later Life. Lon-don: BMJ Publishing Group, 1994.

[14] Martyn CN, Gale CR, Jespersen S, Sherriff SB. Impaired fetal growth and atherosclerosis of carotid and peripheral arteries. Lancet 1998;352:173 – 8.

[15] Frosst P, Blom HJ, Milon R, et al. A candidate genetic risk factor for vascular disease: a common mutation in methylenete-trahydrofolate reductase. Nat Genet 1996;10:111 – 3.

[16] Spaapen LJM, Waterval WAH, Bakker JA, Luijck GJ, Vles JSH. Detection of hyperhomocysteinemia in premature cere-brovascular diseases. Tijdschrift van de Nederlandse Verenigning voor Klinische Chemie 1992;17:194 – 9.

[17] Larsen K. Creatinine assay by a reaction-kinetic approach. Clin Chim Acta 1972;41:209 – 17.

[18] Selhub J, Jacques PF, Bostom AG, et al. Association between plasma homocysteine concentrations and extracranial carotid-artery stenosis. New Engl J Med 1995;332:286 – 91.

[19] Lowrie EG, Lazarus EG, Hampers CL, Merrill JP. Cardiovascu-lar disease in dialysis patients. New Engl J Med 1974;290:737 – 8. [20] Parfrey PS, Griffiths SM, Harnett JD, Kent GM, Murray D, Barre PE. Outcome and risk factors of ischemic heart disease in chronic uremia. Kidney Int 1996;49:1428 – 34.

[21] Brown JH, Hunt LP, Vites NP, Short CD, Gokal R, Mallick NP. Comparative mortality from cardiovascular disease in pa-tients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1994;9:1136 – 42.

[22] Kawagishi T, Nishizawa Y, Konishi T, Kawasaki K, Emoto M. High-resolution ultrasonography in evaluation of atherosclerosis in uremia. Kidney Int 1995;48:820 – 6.

[23] Tkac I, Silver F, Lamarche B, Lewis GF, Steiner G. Serum creatinine level is an independent risk factor for the angiographic severity of internal carotid artery stenosis in subjects who have previously had transient ischaemic attacks. J Cardiovasc Risk 1999;5:79 – 83.

[24] Bots ML, Launer LJ, Lindemans J, Hofman A, Grobbee DE. Homocysteine, atherosclerosis and prevalent cardiovascular dis-ease in the elderly: the Rotterdam study. J Intern Med 1997;242:339 – 47.

[25] Mcquillan BM, Beilby JP, Nidorf M, Thompson PL, Hung J. Hyperhomocysteinemia but not the C677T mutation of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase is an independent risk de-terminant of carotid wall thickening. Circulation 1999;99:2383 – 8.

[26] Malinow MR, Nieto FJ, Szklo M, Chambless LE, Bond G. Carotid artery intimal-medial wall thickening and plasma homo-cysteine in asymptomatic adults: the atherosclerosis risk in the community study. Circulation 1993;87:1107 – 13.

[27] Brattstrom L, Lindgren A, Israelsson B, Andersson A, Hultberg B. Homocysteine and cysteine: determinants of plasma levels in middle-aged and elderly subjects. J Intern Med 1994;236:633 – 41. [28] Folsom AR, Nieto FJ, McGovern PG. Prospective study of coronary heart disease incidence in relation to fasting total homocysteine, related genetic polymorphisms, and B vitamins. Circulation 1998;98:204 – 10.

[29] Spence JD, Malinow MR, Barnett PA, Marian AJ, Freeman D, Hegele RA. Plasma homocysteine concentration, but not MTHFR genotype, is associated with variation in carotid plaque area. Stroke 1999;30:969 – 73.

[30] Brattstrom L, Wilcken DE, Ohrvik J, Brudin L. Common methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene mutation leads to hy-perhomocysteinemia but not to vascular disease: the results of a meta-analysis. Circulation 1998;98:2520 – 6.

[31] Kluijtmans LA, Kastelein JJP, Lindemans J, et al. Thermolabile methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase in coronary artery disease. Circulation 1997;96:2573 – 7.

[32] Manolio TA, Kronmal RA, Burke GL, O’Leary DH, Price TR. Short-term predictors of incident stroke in older adults. Stroke 1996;27:1479 – 86.