In: improving Workplacc Lcarning Editors; G. Castleton et al., pp. 3-19

ISBr.\ 1 59451-566-9 O 2006 Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Chapter

I

LnennING

AT

WoRK:

OncIxISATIOI{AL

READINESS

AI\D

IXNTVTNUAL

EXCECEMENT

Stephen

Billett

INJrnonucrIoN

This chapter addresscs the theme of this book by discussing factors that influence how leaming can best proceed

in

workplaces"ln

particular, the discussion focuses on the dual considerations of horv workplaccs afford opporfunities for leaming, on the one hand, and how individuals eiect to cngagein

activities and with the support and guidance provided by theworkplace, on the other hand. Together, these dual bases for participation at work, and the

relations between them, are held as being central to understanding the kinds of learning that lvorkplaces are able to provide to those r,vho work within them. Accordingly, the preparedness

or readincss of thc rvorkplace to afford and support opportunitics stands as a key determinant

of

the qualityof

learningin

workplaces. These affordances are salientto

both structured workplace learning arrangements, such as mentoring, as well as the contributions to learning accessed through cveryday participationat

rvork. Evidence and illustrative instances of enterprise readinessand

its

consequencesare

provided throughthe

findings

of

aninvestigation

of

guided iearningin

five

different kindsof

workplaces (Billett, McCann&

Scott 1998; Billett 2001a). It was found that guided learning strategies (Modelting, Coaching, Questioning,

Analogies

and

Diagrams')

augmentedindividuals' learning

tlirough contributions that cannot be realised through everyday work activities alone. However, acrossthe five enterpriscs, the frcquency

of

guidcd leaming strategy use and pcrccptionsof

their value were diverse. Factors such as variationsin

enterprise size, activities or goals did notftrlly

explain these differences. Instead,from this

sfudy the salienceof

the

enterprises' readiness to afford activities and guidance were identified as a key factor- Overall, learnersafforded the richest opportunities for learning and how engaged with what was being afforded reported the strongest developrnent. This readiness goes beyond the preparedness for guided iearning to proceed (c.g. the prcparation of mentors), although this was an important l-actor.

Stcphcn Billctt

the invitational qualities lor workers to parlicipate in ancl learn through work' Therefore' the degreebywhichworkplacesproviderichleamingoutcomesthrougheverydayactivitiesand intentional interventions

will

be shapecl, by its rc-acliness lc'r allcrrcl opportunitiesancl support

-t

tff;:lieless,

how individuals elect to engage

in

workplace tasks and interactions also influences rvhat they learn through thcir work*ttit'itit'

and intentional iearning opporlunities' Even when workplaces afford rich opportunities to leam' not all individuals participatedfully' collaborativelyoreffortfully'Conversely,someworkersassisttheleamingofcoworkersby making invitational o

,"nrkplu."

r.vith low levclsof

readiness and support'In

doing so they extendtheopporltrniticsandalfordancesofthatworkplace.Thesedualandinterdcpendent

basesprovideawayofunderstandinghowlearningatworkproceedsandhavebeen

conceprualisetlas.co.participationatrvork'*thereciprocalprocessofaffordancesand

engagement (Biilett zobru). Findings form the study

of

guided learning infive

enterprises(Billett, et al. 1998; tsillen 2001a) evaporates and illuminates bases to discuss aspects of co-participation and

its

potentialfor

understanding and perhaps improving learningin

ther,vorkplace. This inclurtes itlentifying factors that shape how opportunities and

interactions proceeded differently across these workplaces ancl how, conespondingly' bases

for rvorkplace learning were manit'ested in each work setting' It conciuded that for learning to

best proceed

throughworkplaceactivitiesrequires(i)*appropriatesupportforthedevelopmentof

invitational workplace learning environment,

'tiii

,r,.

needto

tailor

workplace leaming curriculumto

parlicular enterprise needs,inchitling

the

readinessof

thoservho

areparriciparing;

(iii)

encouraging iarticipation by both learncrs and,those guidingthe learning

and(iv)theappropriateselectionun.ip,.pu*tionofthecoworkerstoguideandmonitor

corvorkers' leaming'

PlRltctpATIoN

AT

WoRK

Ar\D

LEARNING

Thereisnoseparaticlnbelweerrerrgaginginrvorkpracticeandlearning(Lave1993). Everyday activities, the workplace,

otherv/o,t.,,

and observing and listeningare consistently reported as the sources for workers to learn their vocational activities through work (Billett

1999a;

Billett

2001a).Tllc

rnomcnt-by-ilomciit learningor

microgcnelicdcleloprncnt (Rogoff 1gg0;

lqssjiir"r

occurs arwork is shapecl by rhe activities inclividualsengage in' the

direct guidance tirey access and also the indirect contributions provided by the physical and socialenvironment(Billett2001a).Dep.endingontheirfamiliaritytoindividuals'rr'orkplace activities either act to reinforce, assist

in

the refinemenl or the generationof

new formsof

knowledge. This ongoing and moment-by-moment learning is what Piaget

(1966) referred to as accommoriation

"and

assimilation, the ongoing process

of

reinforcing and refining our krowledge as we engage in conscious thoughiu,riu"rion ln:1:]*"0

in world' Thequality

of

workplace

leaming.iili

t"

therelore be influencecl by how participation in rvork activitiesand

access thc guidance proccetls and the support providcd'

Consequentiy,l'o,"learningthrough'uo,kp,'o.."dsneedstobeunderstoodintermsof theafforclancesthatsrrpportorinhibitindividrrals'engagementinwork.Theseaftbrdances are constifuted in workplaces.

lt

seems that beyond judgements of individuals'competence' opportunities

to

participate are distrib.,t"don

hases including race(Hull

1997),gend'er

(Biere n'orkp

I 99i.

\\-hos u.'ork1 deter-r 1998r ment( (Bille oppoi 'oid-t dilfer perso those contil oppol

I 99S

and r

\

inte n' rvor-ti n'ho Oost, attor same appr(to p..

co\\ (

*

orl distr learr and n'orl fami asp attorLcarning at \\/ork

(Bierema 2001; Solomon, 1999; Somerville this volume), worker

or

employment stalus,*'orkplace hierarchies (Darrah 1996;1997) workplace demarcations (Bernhardt 1999, Billett i995; Danfcrrd 1998) personal relations, rvorkplace cliques ancl affiliations

(Billett

1999b).Whose participation is encouraged and lvhose is frustrated then becomes a central concem for rvorkplace learning. Relations between supervisors

and

workersand

among rvorkers determine horv rvorkplace interactions proceed and the basis by rvhich they proceed (Danford 1998). For instance, at oneof

thefive

workplaces, some workers interpreted the use by mentors of questioning as a leanring strategy as inter-rogation to ascertain how little they knew (Billett etal.

1998).Of

course, workplaccs are contested environments. The availabililyof

opporfunities to participale may become the bases

lbr

contestation between newcomers' or 'old-timers'(i.ave&

Wenger 1991), full or part-time workers lBernhardt 1999); teams with different roles and standing in the workplace (Darrah 199;Huli

1991); between individuals' personal and vocational goals (Dan'ah 1997) or among institutionalised arrangements such asthose representing workers, supervisors

or

management (Danford 1998).For

instance, contingent workers (i.e. those who are part-time and contractual) may struggie to be afforded opportunitiesto

pailicipatein

the ways available to full-time employees (Bemhardt et. al.1998). Part-time women workers ha"'e particular difficulty in maintaining their skills currency

and realising career aspirations (Tam 1997).

Moreover, limits on participation are not restricted

to

contingent workers. Support andintentional opporrunities for learning are distributed on the basis of perceptions

of

workers' rvorth and statns Fnterprise expendinrre on employees' further development privileges those r.vho areyoung, highly educated, male andwhite (Rrunello&

Medio 2001,Groot, Hartog&

Oosterbesk 1994). Lower stalus workers may bc dcnisd the affordances enjoyed

by

highstafus rr,'orkers (Darrah 1996). Affiliations and demarcations rvithin rvorkplaces also distribute affordances. Plant operators

within

an amalgamatcd union invitcd fcllow plant workers to acccss training and practice while restricting opportunities to other kindsof

lvorkersin

thesamc union

(Billett

1995). Also, tradeworkers rcfuscd to assist apprcntices unless they hold appropriatc union affiliation. Personal affiliations in rvorkplaces also determine who is invited to participate, what information is shared, and u'ith u,hom, how work is distributed and horv coworkers' efforts are acknowledged (Billett, Barker & Hemon-Tinning 2004).It follows that workplaces are not benign and the invitational qualitiesof

the workplace are not evenly distrihuted. The salient conceln is that more than participation in work tasks. opporhrnities for learning are distributed asymmetrically. Tndividuals' ability to access and observe coworkers and workplace processes assist in developing an understandingof

the purpose and goals for r.vork activities (Billett 2001a). Therefore, the degree by which individuals can access both lamiliar and new tasks, and interact with coworkers, particularly rnore experienced workerS,,as part

of

everyday work activities,will

influence the richnessof

their learning. Moreover, affordances including the openness, suppofi and preparedness ofmore experienced coworkers r,vill also influencs the efficacyof

intentional stratcgics such as mentoring, reflection on action and coaching (Billett 2002).However, and as foreshadowed,

while

acknowledging the contributions afforded by workplaces, how individuals' decide to cngagc with workpiace activities and guidance alsodctcrmrnes the quahfy of what they lcarn. Leaming nclv knou,lcdgc (i.e. concepts about r,vork,

Stephen Bilictt

in work activities is unlikely to result in unquestioning participation or unquestioned learning (i.e. as in socialisation or.n.ulturation) of what is afforded by the workplace' Individuals are active agents

in

what anci how they learn from these encounters' Tlierefore,it

would be mistakento

ignorethe

strengthof

human agency (Engestrom&

Middleton 1996)' In considerationof

this, wertsch (1993) distinguishes between mastery and appropriation' Mastery is the superficial acceptance of knowledge coupled rvith the ability to satisff publicperformance requirements, yet which lacks the belief or commitment by the individual' The unenthusiastic utterance

of

standard salutationsby

supermarket check out operators andairline

cabin crews are illustrationsof

mastery- Appropriationis

the acceptanceby

theindividuals of what they are learning and their desire to make it part of their own repertoire

of

understandings, procedures and beliefs (Leontievl98l)'

For instance' because of their distrust of mine site management, workers in coalmines may demonstrate mastery of some employerrequestsforcertainprocedurestobeadoptedundernegotiatedagleements'while

appropriating the ideas and -eans of working propose<l by their union delegates' Participation

in

work

can leadto

heightened concerns aboutwork

practice andthe

development orconsolidation of values and practices that are distinct from those required to be exercised in the parricular work practice isee Hodges 1998). As Goodnow (1990) advises' individuals not

oniy iearn to solve problems, they learn which problems are worth solving'

All

this suggeststhe need

to

consider how individuals electto

actin

the workplaces' aswell

as what the workplace affords individuals'LuRNING

THRoIIGH

WoRK

The contributions to individuals' learning accessed through everyday work activity have been shown to develop many of the requirements for performance at work

(Billett

1999a)' ongoing engagement in goal-directed work activities, direct interactions with coworkers' and observations by other workers, the workplace and workplace artefacts all contribute to this learrring. As noted, this kindof

moment-by-moment learning (Rogoff 1995) constitutes an essential elementof

human cognitive development as a productof

engagement with social practiceof

the workplace. However, there arelimits to

learning through participating in everyday work activitics. Thesewill

vary from workplacc to workplace' Such variations arcpremised on the kinds of knowledge to be leamt in the workplace (e'g' the support available'

kinds

of

work

practices adopteJ).The

limitationsof

iearning through everyday workactivities include failing to develop the understandings, procedures and values thatpannot be learnt through intlividual discovery alone Ericsson

&

Lehmann 1996)' For instance' many performance requirements are not observable or even easily understood' equally principles that underpin performance need to be understood, yet these are often not accessible withoutthe

guidanceof

more experienced coworkerswho

can assist makingwhat

is

opaque accessible(Billett

1999a). Many procedures---

the

'tricksof

the trade'or

heuristics ---required for vocational practice need to be modelled and explained by experts who then needto

organise practiseuni -orrito.

the developmentfor

less experienced coworkers (Billettlggga).

Guided learning strategies (e.g. modelling, coaching, questioning, diagrams andanalogies) to be used as part of everyday work activities have been identified and trialed in order to augment the learning arising from everyday work activities' These strategies were

shc

Iml

em

trat

CXI

a( .1

SI

ei

e1

wo

knr

pra

sitr

wo

ngr inc

WC

afl

op

the

the

fir

t9 'u (i.

fgr

re

e! di

SU

in fir le

a(

Learning at \\/ork

shown to enrich the development

of

working knowledge (Billett etal

1998; Billett 2001a). Importantly,this

knowledge,with

its

opaque concepts, sophisticated procedures andeurbedcled values

is

of

the kind required to respond eflectivelyto

workplace tasks and totransfer to other circumstances, yet is difficult to leam without the close guidance of a more expert partner.

The deveiopment of these kinds of knorvledge has benefits for both individuals and the

workplaces

in

which they practice. They offer individuals the possibilityof

applying their knowledge more broadly thanin

the circumstancein

whichit

was learnt andis

currently practiced.This

capacity providesa

basisfor

the portabilityof

vocational skillsto

new situations and other workplaces and also for engagement in increasingly complex tasks. For workplaces, these capacities offer the prospect of a work force able to respond optimaliy tonew

and emergingwork

tasks. Nevertheless,both

engagementin

everyday activities, includingthe ability

to

secure direct and indirect guidance and the useof

intentional workplace learning strategies, are dependent upon the duality between how the workplace affords these experiences and alsohow

individuals electto

engagewith

the kindsof

opportunities and contributions afforded by the workplace. Without the invitational qualities that assist individuals engage and learn and without their willingness to participate effortfully, the potential of workplaces as leaming environments is unlikely to be reaiised.

WonrcplACB

AFFoRDANCES AND

INDIvIDUAL

Excacnnrurr

To illustrate manifestations of co-parlicipation at work and consider its implications, the

findings of an investigation of leaming in five workplace sites are now discussed (Billett et al.

199; Billett 2001a). This investigation examined the efficacy of the contributions of both the 'unintended' (i.e. e,-eryday acti,-ities, obser,-ing and listening, other workers, the w'orkplace) rcferred

to

as thc leaming curriculum (Lave 1990) and intended guided leaming strategies (i.e. Modelling, Coaching, Analogie,s. Diagrams, Questioning)to

ieaming the knowledge required for work performance. Although not its intended focus, the salience of organisational readiness and individual engagement was a key finding of this study. During this study, it was evident that the preparednessof

each enterprise to support effective learning in workplaces differed significantly and that these diffcrcnccs had conscquencos for holv interactions andsupport proceeded. Moreover, the study provided evidence

of

how

individuals' actions impacted on their own learning and the learningof

co-workers they were assisting. The findings also identified thc roleof

individual agencyin

both assisting and participation in learning in workplaces" The procedures used in this investigation included preparing mentors, selected by the enterprise, in the useof

guided leaming strategies as partof

their everyday actions in their workpiaccs.The data gathering proccdures included monthly interviews

with

learners that elicited accounts of recently undertaken workplace tasks, over a six-month period. They were askedabout whom

or

r.vhat had helped thcm complete these tasksor

lvhat kjndsof

additional suppofi they needed to successfully complete tasks. During these interviews, quantitative datawere gathered from the learners in the form of measures of the weighting of the efficacy

of

Stcphen Bilictt

workers, the Workplace, which had been identified as the elements of the workplace 'leaming curriculum'

(Billett

1999a).Also

included were the contributions providedby

Modelling, Cooching, Questioning, Diagrums and, Analogies. These had been identified as strategies that were(i)

likely to assist learning the requirements for work performance that probably would not be learnt alone and(ii)

could be used as part of everyday work activities" Final interviews with the learners and their mentors elicited data about the overallutility

of guided learning, including the strengths and limitations and scope for improvement.In

addition, measuresof

conceptual and procedural development were used to identify evidence ofchange to the base

and organisation of individuals'working knowledge (see Billett et al. 1998). Throughout the

six-month investigation, the researchers also made notes and observations about each of the

workplaces and how the provision

of

workplace leaming was manifestedin

each setting, These data are referred to in the discussions that follow. In particular, the three largest of thefive enterprises are discussed below.

The first enterprise, Healthylifel is a large food manufacrurer, with a history of the in-house training of its workforce- Accordingly, workers in many areas of the plant were quite familiar with work-base<l programs. Two work areas within tlealthylife were involved in this sfudy. The first was the product development area whose purpose

is to

develop,trial

andmonitor products. Most of its staff were tertiary-educated food technologists. Four staff acted

as mentors

to

five learners(Hl,

H2, H3, H4, H5). The mentors and learner enjoyed closeproximity, working

in

the same building and having easy accessto

each other and notseparated by shift arrangcments. They also sharcd the same lunch and recreational facilities, were earlier

work

had indicated informing discussions about r,vork practice often occur(Billett

1994). Strong relations existed among manyof

the workersin

this area, bound bycommon interests and the particular role they played within Healthylife. These workers were perceived

to

be high status and accommodatedin

a buiiding away form the main piant, referredto by

other workers asthe'Taj

Mahal'The

second work area was occupational health and safefy, with one experienced staff member mentoring a peer (H6) who had beenrecruited recently. These individuals were physicaily separated from each other. Although working in the same plant, the mentor and his mentee u'ere located

in

different parts of theplant and were unlikely

to

encounter each other unlessby

arrangement. The new recruit believed his knowledge and approach to work, a product of 25 years experience, was superior to his mentor's. The neu. rccruit also disagreed rvith the approach to occupational health andsafety adopted at the Healthylife plant. He wanted to introduce a more rigorous and regulated approach to occupational health and safety"

Both learners and mentors reported quite distinct outcomes from each of these two work

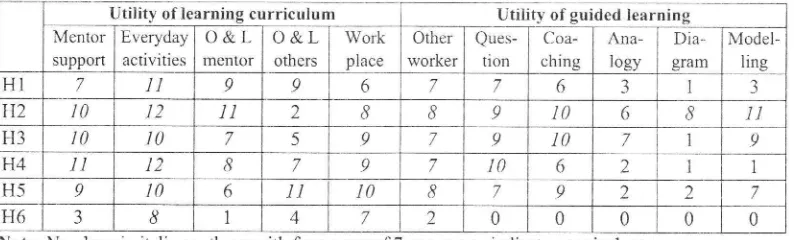

areas at Healthylife. In Table

l,

quantitative data linking workplace activities and efficacyof

contributions to the leaming of work tasks is presented. In the right hand column, the learners

(H1-H6) are listed. The columns

to

theright

are each data representing measuresof

theeffectiveness for their learning from eash of the contributions. The two sets of contributions are organised under the headings

of

'learning curriculum' and 'guided learning strategies'. Measuresof

efficacy are indicated by numbers that indicate frequencies that the leamers weighted eachof

the contributions as either 3-4-5 (usefuito

very useful), outof

5,to

aworkplace task" Responses weighted 1 and 2 (not useful), were set aside to tighten the data

being presented. Given the

four

interviews each recalling three workplace incidents, themaxtlr times

assi stir

very u

once).

often t

freque

Table

Le Eve4'6 ntenlor most vi

develol about t

use cot learner

access

learnin develol iearninl

occupa'

product prernist

of

his ilearner

r.veighti

These e

joint

ii

contribr

suggeqr

critical Tht highiy <

HI H2

H3

H4 H5 H6 Note: ir

Learning at Work

maximum possible number of responses

is

12. For instance,Hl

reported Mentor Support 7times out

of

a possible 12 as 3-4-5 (i.e. very useful) when responding to their efficacy in assisting with ivorkplace tasks. This responcient reported Et,er1,1l6y actit,ities (11 tines ratedvery useful) most frequently, and Diagrams with the lowest frequency (rated very useful only once). As noted, those contributions whose frequency is typically rated very useful (i.e. more often that

not-7-12)

are bolded in this table, to ease the identification of those contributions frequently reported as being highly effective.Table 1 - Utilit-v of the workplace learning

Utility of learning curriculum Utiiity of guided learning Mentor

support

Everyday activities

o&L

mentoro&L

others

Work

place

Other worker

Ques-tion

Coa-ching Ana-logy

Dia-gram

Model-line

H1 7

tl

9 9 6 7 7 6 J I 3H2 IA I2

tl

2 8 8 9 10 6 8ll

H3 IO t0 7 5 9 7 9 10 7 I 9

H4 11 t) 8 7 9 7 t0 6 2 I

H5 9 10 6 IO

I

7 9 2 2 7H6 J 8 4 7 2 0 0 0 0 0

Note: Nr-rmbers in italic are those w'ith frequency of 7 ormore to indicate a typical response

Leamers

in

the product development area, (H1,H2, H3, H4, H5)

valued most theEveryday activ*ities, Support oJ'the mentor, leaming through, Observing ancl listening to the

ntentor and the workplace. Of the guided leaming strategies, Coaching and Questioning were most valued in this work area. The perceptions of utility of the guided learning by the product development mentors' were focussed on their efficacy

with

learning process,with

views about their limitations and suggestions for improvement being focussed on how thc strategy use could be improved and refined, and what was required for this to happen. Similarly, thelearners in this work area supported the guided leaming approach for its capacity to provide access

to

procedures and lcarning new rcquiremcnts, the one-to-one approachto

guided leaming, its shared problem-focus approach and its effectiveness. In these ways, the product development section seemsto

have invited the learnersto

participate and supported their iearning through guidance andwilling

collaborative actions. However, the dataliom

theoccupational health and safety area prcscntcd a different pattcrn

in

termsof

outcomcs andproducts. Here, the interactions and perceptions of the guided learning strategies were largely prerniscd on the participation of the new ernployee (H6). He seemed to resist the best eflorts

of

his mentor, designatinglittle

valuein

guides' contributions to his learning. Instead, ihis learner placed considerable value on those contributions thatdid

not involve the mentor, rveighting Everytday activities and the ll/orkplace as key sources of his leaming (see Table 1).These elements reflect individual engagement, rather than collaborative problem-solving and

joint

interactions. Noticeabiy,as

presentedin

Table

1, he

placedlittle

value

on

thecontributior-rs arisiirg

from the

guided strategies acrossthe

six

month period.He

also suggested that the menloring process only rea.lly had utility u,ith induction processes and ',vascritical of the selection of the individual paircd as his mentor.

The second enterprise, Albany Textiles is a large textile manufacturing company. It has a

[image:7.595.68.465.197.317.2]in-Stephen Billett 10

housetraininghadoccurredinthemanufacturingplantatthetimeoftheinvestigation,sothe guided re arnin g strate gi es to b".

Tul"l,:"^:-

;'::::

Y"tI

iJT:$:::

;T"Ji#:

li:

two

r'

not ab mentLl appre( persp(not

clgeneri

work; the le develr

I

811

l.cr s

iA19

tro

E

tA22 iA23141

:-\r5 'Ar1\ote

empof

a,rerlc \\'er( disu surp for guit thei mal nleI

;- t.

rllU I

tor -- r

lah

11'e1

iJ:::#Hii#iH:;il;,';'tn

.o-*,,ni.ation

abour the purpose or the proiect mthisworkplace.Forinstance,despite."o'*,-""aprovisionofinformationtobriefthe

leaming guides una

to't""

in"otutO intt'"

i'"1"ti tlti **::1-::"n""*ing'

The selected mentors reported at the train-the-learning guide workshops

to

just

having been informedabout the project that morning' Some

*"'"

O'tt"

""pi"ioo'

about the motives

for

their selectionaslearningguides.othersw",enot"onfidentabouttheirabilitytoacteffectivelyin this role. Later,it

was found that many workersin

this plantwere uninformed and quite suspiciousabouttherr.o"**conductedbythelearningguides,andalsowhysomeofthem had been selected as guides' There was.

"k;';t;;;;;

J]"tl

:,l-orker

autonomv at this workplace that may haie inhibited individuals', enthusiasm to participate' For

example' unlike othersites,theseworkerswerenotabletomut."theirownappointments.Somebodyelsehad

to

do thatfor

them.ooo,

u consistentil;i;g

from this site was thatmentors who had multiple learners to guide reported tn"

a"*uni,

"as

being too great' The workers that comprise both mento* urra

r"uJJ^-tvpi""'v

lackedr"r-"i*a

a]ra certineo vocationalpreparation for their work. There were exceptions, 1".g.

,""rii*

-echanics), butthe majority of the workers at

Albany Textiles were not iertiury "ducatei.

A

rangeof work

areas across the plant was

involvedinthetrialingoftheworkplace.learning'Theseareascomprisedthewarehouse

(A17, A18,

arl;,

texiif, mechanics (A20'At1'

a2l)'

spinningullu (A23)' wet finishing area (A24) and qualitv

t"tt'"i fo";

una-u"iinltg

"'""''iAZ

9'

O'n

The worksite has shift arrangements whicrr meant that although

;;;;-

"ngug"din

activities in the same physical location,unlesstt'ementorsandtheirallocatedlearnerswereonthesameshiftitisurrlikely theywill

inreract"r;;-;teveryday

ruorkflu."

activiry' Many rvorkareas \\'ere noisy and

hearing protection irul to be worn.

rni,

*uii

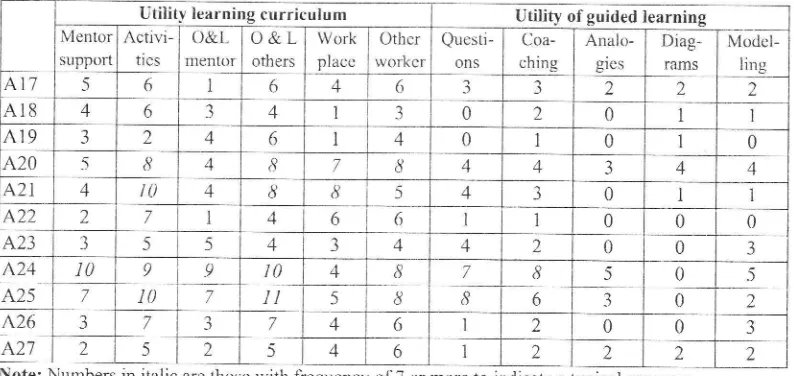

,om" forr1}sof oral communication difficult' The data

or.r"rrlJ in

Table2

i"di;"

;at,

asat

the other sites' thecontributions comprisingthe"learningcurriculum,werevaluedmorethanthe,guidedlearningstrategies'.

However"thefrequencyoftheguided,t'ut"gl",useand-theirreportedefficacyatAlbany

Textiles

*u*

U"to"o1t",

of othlr

sitestr."?ff"tt,

McCann&

Scott 1998) Overall' the learnersreportedlhalEverydayactivities,.observingandlisteningtoothersandotherswere most effectivein

securing workplace knowledge. However,with

the exceptionof

two learners,unlikesomeothersiles.Menrorsupportwasnotgenerallyreportedpositivelvasthecomponents

"f

th.

i;";g

curriculum.Like Healthylife, there were variations in perceptions

of

views, even when considerationi,

tri.n

or

different work areas'In

Table2'

data are

presentedabouttheefficacyofthecontrib.,tio,',tolearninginthedifferentwork.areasthat

are delineatetl by

h;;;;"tul

li"t''

This table is presentedas per Table l '

Like

other workplaces, the contribuiion, or the 'learning curriculum' wasreported as

being more .rurrr.a "rrun

the .guided

r**jrt

ttt.,"gies'

whi"h

wasto

be

expected' As anticipated, Ev-etyday activities, Onr"r.-iiig;'d

,U*rin,

and Other workers are reporled as

havingthehighestlevelsofeffectivenessinassistinglearnersaccomplishworkplacetasks.

However,overall,thedatareportsto*",*"u,.,,.,ofefficacythanatHealthylife.The

frequencybywhichguidedlearning,t'ut.gi.,wereusedwi:i''"lower.Significantly,there

were only two rnstaices where the guided learning strategies

were rcported as commonly provi di n g .

".

o

:,

: 1_'!"*'*::::

rx*::

;ruff;:

ffi::In:

i:'i:T:,ii#

il1;tri,'i

ili*t*,TJl#J:"ffiidence

or a mentor n,o.,ioinr strons supportror these

Tablt

I

I

Lcarning at Work

two workers. This mentor, who was assigned

to

A24 also assisted .A25 when hermentorwas not able to provide guidance. In contrast to what was happening elsewhere in this plant, this mentor usedtlie

guided learning strategies ft.equently andin

ways thesetwo

leamers appreciated and repofied as being quite effective. This example provides another instance andperspective on how individuals elect to engage in the workpiace, and how that engagement is

not

constrainedby

thelevel

of

the affordances being providedby

the workplace more generaliy. This mentor was ableto

overcome someof

the limitationsto

learningin

theworkplace and made

it

more invitational for the two learners. The consequence was that that the learners' reported highlevcl

of

efficacy themselves and also measuresof

conceptual development were stronger than for others in that workplace (Billett 2000).Table 2 -

Utility

of contributions to workplace learningNote: Numbers in italic are those with frequency of 7 or more to indicate a typical response

fhe

mentors' ovcrall pcrceptionof

the

guided leaming processat

Albany Textiies emphasised (i) the motivational outcome for the learners,(ii)

its provision of another sourceof advice and

(iii)

making leamers think for themselves. In addition, some mentors reported reflected on how they went about their work. Concerns about the gurded learning processwere associated with lack

of

preparednessof

both learners and mentors, and having other distractions (i.e. being too busy, meeting production deadlines) that inhibited its use. Not surprisingly, suggestions for the improvement of guided learning emphasised the requirementfor

a more thorough and tightly focused preparation and having the timeto

implemen't the guidcd learning. The mentors' responses to theutility

of the individual strategics emphasisedtheir

contributionsin

developing understanding, (e.g. create images, explaining things),making the learner doing the thinking and the capacity to develop relationships between the mentor and the mentees.

In

addition, the strategies were proposed as havingutility

for induclioit, setting appropriate goals and providing a relevant process for lcarning. The basisfor strategv use bv mentors were reoofied as being their

(i)

appropriateness to the work site and activities and(ii)

the mentors'ability to

implement these strategies. So, the mcntors valued the strategies for the very reasons the literature advances their utilify. However, there were frequently stated concerns about the implementation of these strategies. The reluctancell

Utility learning curriculum Utility of guided learning Mentor

support

Activi-ties

O&L

mentor

o&L

others

Work placc

Other worker

Questi-ons

Coa-ching

Analo-gie s

Diag-fams

Model-ling

417 5 o I 6 4 6 J J 2 z 2

A18 4 6 -) 4 3 0 2 0 I

A19 J 2 4 6 4 0 I 0 0

A20 5 B 4 8 7 8 4 4 J 4 4

p'21 4 IO 4 8 B 5 4

0 I

422 2 7 4 6 6 I 0 0 0

A'23 3 5 5 4 3 4 4 2 0 0 J

424 IO 9 9

l0

4 8 7I

5 0 5425 7

t0

7 1t 5I

8 6 3 0 2426 J 7 -) 7 4 6 I 2 0 0 J

[image:9.595.77.474.239.427.2]t2 Stcphcn Bilictt

of

the leaming guides to use the strategies was malched by their limited responses when interviewed.'fherefore, the data aboul the weakresses of these strategies are restricted.However, and

in

contrast, the lnenteesat

Albany Tertiles were not meagerin

their commentarics aboirt the overall efficacyof

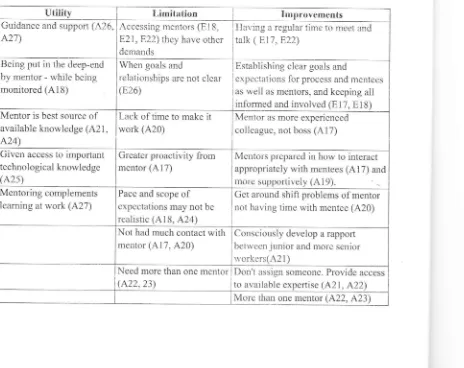

the mentoring process (see Table3).

Their responses are illustrative of workplace readiness and assisl understanding horv this readiness influences tvorkplace leaming. The rcsponses in Tabie 3 represent stalements of the learners' views about theutility

and limitations of guided leamingin

their workplace, and how they could be improved. Where two or more of the respondents mentioned the same itcm they arepresented togcther. The number

of

comments presentcd as limitations and improvements rc{lected the employee's frustration r.vith the guitled iearning process and their dcsire for improvements to be implemented. As rvith similar ciata a( the other work sites, these datawere gathered at summative interview with the learners.

The learners generally supported guided learning as a vehicle

for

the developmentof

workplace klowledge and emphasised the mentors' key role as a source of that knowledge. Engagement in activities that were effortful and demanding (e.g. 'being put in the deep encl'), the monitoring by the guide and support while leaming ancl assistancc

in

gaining access to'hard-to-learn' knowledge (e.g. technological knorvleclge) rvere

all

vaiued.In

sum, theseviews are consistent with what was proposed would be achieved through the enactment

of

guided learning.

Table 3 - Mentees'perception of the mentoring process at Albany textiles

Utility Limitation Improvements

Guidance and support (A26,

1\27)

Accessing mentors (E 1 8, E21 , E22) thcy have othcr

demands

Flar.,ing a regular time to mcet and

talk ( F.l

l,

E22)Being put in the deep-end by mentor - while being monitored (A18)

When goals and

relationships are not clear

(E26)

Establishing clear goals and

expectaticlns for process and mentees

as well as menlors, and keeping all informed and involved (E17, E18)

Mentor is bcst source of available knowledge (A2

l,

424)

Lack of time to make it work (A20)

Mcntor as more experienced colleague, not boss (A17) Given access to important

technological knowledge

(A25 )

Mentoring complemenls

leaming at work (A27)

Greatcr proactivity from mentor (A l7)

P"*

""d

*"e"

"f

expectations may not berealistic (A18, A24)

Mentors prepared in how to interact

appropriately with mentees (A 17) and

'n9l9j!!!91'"eU4ry).

'

.Cct around snift proUt"n.rs

otnent-not having time with mcntee (A20)

--- l

I___

,:l

Not had much contact with

mentor (A 17. A20)

Need *ore tnun one ,*nror. t A22. 231

l

I

Consciously develop a rapport

betwcr'n jrrnior and morc senior

rrork.'r:(A2l)_

Don't assign someone. Provide access

to available erpertise (A2 I ,

A22)

_Morc than one mentor (A22, A23)

Hou t

learning. who n'ere

."vas to bc

there n'er,

and the n<

lor impro' process at

the mentc includes t

(iii)

the stand (ir 1

responses

proceed ir The distributit into its nc'

the head o

The secon

lines or re

and thcir r

time (e s

kilomeire-r nSnlors '.-.

out.

Of

il-(C11) u.rs1.ears and

'learninE

;

contriL,r,rtic x orket's (-)

Once or :',r

u-ork1oa,l SOtlrceS rrf have

cr.i,:

on the iLrplJeal

uitlt,

The ir: _r,-ri,le,l .;,.--;-,

,:--:l'11li rrl-! ',1ntn: l1 r1 \ i_.i.trr,- r !,i{.iili:rii!

;s--ipl:,-;ii

-:--.-,.-..

..v---!--r _ [image:10.595.69.533.357.725.2]

Learning at Work 13 Horvever, there were consistent concerns about

the

limitationsof

this

approach to learning' These limitations comprised concerns about accessto

and availabililyof

mentors who were often unavailable ancl having greater clarity in the goalslor

the process ancl what u'as to be learnt. as well as being more realistic about the goals to be achieved. Inaddition. there were concems about the role of, contact with the mentors

and relations between them, and the need for there to be more than more than one mentor, for each ieamer. ,rhe

proposals for improvement stemmed from these concerns but went further to suggest how the mentoring process at Albany Textiles should be improved by having: (i) clear goals and expectations for the mentoring process, for both mentees and mentors;

(ii)

the preparationfor

mentors that includes building supportive and coliaborative rclationships betweenmentors and leamcrs,

(iii)

the selection of mentors on the basis of their expertisqrather than their supervisory role:and

(iv) a

regular basisto

meetif

work

schedulesinhibit

frequent interactions. Theseresponses provide useful bases for considering how intentional

workplace leaming nee6s to proceed in workplaces where there is limited readiness

and affordances are limited.

The

third

enterprise, powempwas

a

recently corporatised,public

sector power distribution company. At the time of the projectit

was moving through a process of settling into its ne\\r corporate structure and role. The empioyees of this companywerc eithcr based in

the head office or located across the regions to which that the company distributed eiectricitv. The second kind of workers was either thosc who had a responsibility for maintaining power lines or regional administration. Hencc, there was separation between

some

of

the menteesand their mentors Some participants were requirecl at other locations for length;,peri.cls

of

time (e.g' several weeks). This physical separation was frequently quite great (hrrndreds

of

kilometres)'As a

consequence, frequent close interaction betw-een the mentees and their mcntors lvas often difficult to sccure. Many participants in the program subsequentll, dropped out'of

the five leamcrs who commenced the program, only^ on-" finished. This individual (c11) was geographically isolatc<l from his mentor. The companyhad ernployecl

him

for 25years and for 2 years in the particular work area. Nevertheless, he

valued components of the 'learning curriculum', consistently weighted them highly as contributing to his work.

These

contribrrtions included Everyday Activitie.s,

ohsening

anrl listeningto

others

and other workers (Table

5'Cl).

Throughout the six month project, the mentor and menteeonly met once

or

twice'cll

was reluctant to approach the mentor, outof

concernfbr

this person,s workload' As partof

this leamer's everyday activities he relied on other workers as key sotlrces of understanding more about and proceedingwith his work. one factor, which may have contributed to his development was his participation in

a training program that focussed on the topics in which he was being mentored. Also, he was required, as part

orrrir",o.t,iJ

.

deal with issues in which he was being mentoretl on a day_to_day basis.

The important point to be made about Powerup was the very limited affordance for the guided leaming process to succeed in this enterprise.

It

tacked readiness.Essentially,

it

was going througha

pcriodof

transitionin

struclure andat thc

sametimc

movinginto

a

competitive market that was outside the experience

of

mostof

its employees.At

the initial mceting it was stated there was a need for a structured approach to workplace Iearning in this organisation, particularly with workers being distributed across sucha large region. However, dcsptte cttbrts

of

the researchers to malntarn intercst rn thc gurdcd leaming pro,ect, neithcr the support nor readiness within the organisation r.vas forthcoriing for it ro proceed. Hor,vcver,despite this,

cll

persisteclwith

this and attemptedto

find

novel waysto

rvork \4,ith his nominatcd mentor (e.g" making regular phone contact). So again, thercis

cr.idenceof

l.+ Stcphcn Bjllctl

individual acting in the r,vorkplace in ways that are inconsistent with the notms and practices

ol

the work setting-

its affordances. The hndings from this enterprise and the others provide a usef*l basis tcl ri'dersiancl horv indiviiluals can parlicipatein

anci influence the praclice work-based learnin g arrangements'Co-Pa.nTICIPATIoN

AT'WoRK

Thefindingsrcportedabovehrghlightthcrlilferentkindsandconscqlrencesofco.

participation at work (Billett 2001a), the reciprocal process of participation

in

and learning through work. They are drawn from three different workplaces, providing comparisons across and within workplaces about how they afforded participationin

work activities' They alsoprovideexamplesofhowindividualsengaggintheseactivitiesandhowsomeofthis

engagement

is

inconsistentwith

the

normsand

practiceof

these workplaces' their affordances. While these finclings do not riirectly iniorm about how other factors (e'g'gcnder' language,

division

of

labour and

affiliations) shape participation,they

contribute to understanding the process ofand consequences for participation at work and learning through that participation. where the affordances were rich, the reported leaming outcomes associated with working knowledge were generally higher than where this support was not forthcoming' Yet, therc werc instances where individual actions work against the particular qualities of the work piace.At

Heaithylife, the proiiuct clevelopment area was seemingly invitationai for leaming, and accepted anci appreciated as such by the learners' These alfordances included the mentors' intent toprouii"

the rnost effective levelof

guided leaming' supported by an environment that waS Open tO constructlve interactions' Here' concerns about preparation were focussed on how to best use the strategies to make workpiace learning more effective'Thementorsuscdthestratcgiesincombinationandinwaysthatmergedthc.lcarning

curriculum' and use

of

'guided learning strategies'' This mergingis

seen as the dcsirabie outcome,of

intent.ional Larning straregies being used and accepteil as partof

everyday practiceinn

the rvorkplaoe. Inlontrast,

the invitational quaiitiesof

this workplace were seemingly rejected by reluctant participation by the new recruit in the occupational healthand

safety area. His engagement with the workplace and dismissal of the mentor and the guided

stratcgies r,vas quite ,listinct.

llc

most valuc'l contributions that excluded the mentor'Iil

llrcseways, these

two work

areas illustrate how, the afforclancesof

the workplace supportedlearningasreportedbythementorsan<]leamers,whereasinanotherworkarea,an

individual's decision

not

to

cngagein

thework

practice demonstratcd that invitational qualities alonewill

not suffice. However, whereas ar Healthylife, there was evidenceof

an individuai electing to resist engagementin

the guicled leaming and the work practice more generally,Albany.lcxtilesprovidesacase,uvheretheoppositewastrue.Nevertheless,despite the low level of af{brdances to guided learning, one mentor provided high levels of support that lvas both appreciatedby

an<i instrumenral fcrr thetwo

leamcrs' thereby making the cnvironment for lcaming supportive and invitationallt

rvas thcsc learners rvho commcnted how the learning process had openedup

possibititiesfor

them' thereby emphasising theimportantemancipatoryroletobeplayeclbyworkplacesinprovidingforthoseforwhom

there is no option other than to learn in the workpiace, Finally, with Power Up, one individual

struggler arrangell

P rr,t

some

ol

constinlt hog act;.,vorkpla learning sites.

tl

orgar.risr

potentia be jeopr

findins, importa

practic e

overlt r.

thosc- a

system particip

Th

nru-lrbe, consln-l

(Billcii

Hr.rtcl:i

practi.

inarl

indir

ii

rr'orkc-mph:.

values

u orkp overl

l

indir:,betl

.-3t \\ lrl L.eiu e

in dirl

S

iln q'.i a

rbnh: tr3ni. guiJ,

..r'h; i

su sr i.

tri

s.-...r.'h::

Learning at Work t5

struggled and persisted when other coworkers withdrew

from the

workplace learning arrangements, for which the work environment was not ready or committed.Procedurally, the finclirgs indicate the potential

ol

indiviclual agency to both offset thesome of the limitations of an environment whose affordance are weak and also to decide what constitutes an invitation

to

participate. Also, the degreeof

workplace readiness influences how activities and support are afforded as part ofeveryday work activities. The data from theworkplace interviews indicate that the openness and support for learning also influence the

learning occurring through normal workplace activities. Moreover, as reported across the five sites, the potential

for

guided learningto

improve workplace learningis

premised on organisational and individual readiness(Billett et

al.

i998;

Biilett

200ia).

Realising thepotential of learning at these work sites and, in particularly, the mentoring process is likely to

be jeopardized without careful scene-setting and thorough preparation.

In

some ways, thesefindings are commonsensical. That is, the kinds of opportunities provided for learners

will

beimportant for the quality of learning that transpires. Equally, how individuals engage in work practice

will

determinehow

andwhat they

learn. Nevertheless, these factors may beoverlooked

if

the links between engaging in thinking and acting at work and learning through those actions are notfully

understood. Also, beliefs that establishing a workplace training systemwill

alone provide rich learning outcomes, without understanding the dual basesof

participation, is likely to lead to disappointment for both workers and cnterprises.The identification

of

these relations and their consequencesfor

learning also has annmber

of

important concepftral implications Firstly, a current areaof

deliberation within constmctivist theory is to understand the relations between individuals and social practice (Billett 2003). Here, it is shown that rather than being a mere element of social practice (e.g.Hutchins 1991) indir.idual agency operates both interdepcndently and independently in social practices as Engestrom and Middleton (1996) suggest. However, this agency manifests itself in a range of ways. While there is evidcnce of interdependence, there are also examples

of

individuals acting independentlyin

ways inconsistentwith

the norrns and practicesof

thework

practice.This

is

not

to

proposea

shift

backto

an

individualistic psychologicalemphasis. Instead, individuals' socially-derived personal histories (ontogenies)

with

their values and waysof

knowing mediatehow

they participatein

social practice, such asworkplaces. These ways

of

knowingare

the productof

participationin

different andoverlapping social practices

(Lave

&

Wenger 1991) and leadsto

the

stntcturingof

individuals' knowledge

in

particular, perhaps idiosyncratic ways. Hence, relationships between ontogenies and social practice determine participation. The kinds of co-participation at work identified in these three enterprises begin to indicate the diversityof

how relations between the individual and social practice shape individuals' participation and learning andin different ways.

Secondly, in this way the findings emphasise that individuals at work are not passive; unquestioningly appropriating thc norms and valucs

of

workpiaces. Even when support isforthcoming, --- that is the workplace is highly invitational --- individuals may elect not to participate

in

the goal-directed activitiesefforlfully

or

acceptthe

kindsof

support andguidance that are provided. lndividuals need to find meaning in their activities and worth in what rs affbrded

tor

thcmto

participatc and appropnatc. Coai mrncrs,tor

rnstance, were suspicious of work safcty training that thcy believed was aimed to transfer the responsibilityStcphcn Billctt r6

sponsoredbythecompanytheywithdrewtheircommitment,claimingtheirneedsand

aspirations went beyon,iin"

.o*unr's

goals unJ pro..oures whichwere represented in the course(Billett&Hayes2000).Thisindividualiirrlepentlel]cecal1llotbemereiycategtrrisedas positive or negative. Darrah

(lgg7)

iru,ulviaiy

depicted how. inconsistenciesbetween the

values of the workplaces and those of th"

',;;k"r;

lead to a rejectionof work practices that are

not

acceptableto tho'"

u'orkers'I"dJ;' ;;

H.od.ses(i::-:l

has shown' rather than

identiffingwiththevaluesandpracticesoftheworkplace,participationcanleadtoadis-identificationwiththosevaluesandpractice,'n,H"u.t,t-,ylife,thenewoccupationalhealth

andsafetyofficermighthavebecnmore,o-o","n,thanhismentorandhadsomething

special to contribute ,o-in"

on,

policies.'ttn"

rn" workpiace 'Perhaps this suggests different

kinds of invitational

;-;,

;r;

requirecl, such as those ableto assist reluctant partictpants

eitherfindmeaningorparticipateinwaysthatpemitthemtotransformand/orcontest

existing values and practices or finding meaning in this participation'

Thirdly,i,',or-aStheycanofferaccesstoimportantvocationalknowledge,itis

imporlantthatworkplacesarein,,itational.Thefindingssuggestthatwheresupportis

available, workplaceJ can facilitate the learning

of

thathar<i-to-learn knowledge which is requircd

for

vocational practicebut

cannot easilybe

learnt unaidedlt

seems t]r1t forworkplaceleaming'."'o*.""oeffectivelyhowworkersareaffordedopporlurritiesto

participate and

be

J;;;J

in

this

"nd.uuo,rvill

shapethe prospect

of

rich

leamingBemi

L/

Rernl p

T

Bic-ii

.i

Billc' Bilie t1!llr

Biiir

Bili

i1l

outcomes"

CoNct-tlstoll

hsummary,althoughtheguidedlearningstrategiestrialledinthefiveworkplaces

demonstrated that when they arc uscd frequentiy, and in

rvays supportive of the work tasks individuals are cngaged

in'

that they. canO"tJ"O

muchof

the knowlcdge required for workplace perlbrmance. These strategies

""r*"riin"

contributions provided

by

everyday participation at work.n*"u.r,

una"rpinniig irott',or

these^kindsof

contributionsis

co-participation. That is},o*-tt.

workplace afford'sofoo*nut",

for individuals to engage in and besupportedhr"u,ni,.,ginthe.'o,tptuce.Accordingly,toimproveworkplacelearningthere

nill

a nccd for(i)

appropriare dcvclopmcnt onenir.-.ntation

ofworkplace environmilnts that invitational;

(ii)

.

,"iiori",

of tt.,"*nrtplu""

learning curriculumto particular enterprise needs, inelu<ling

trr"

,"uJin.lrs

of

both the

iearners anclthe

guides;

(iii)

encouragingparticipationbyboththo,.,"hoarelearningandthoseguidingthelearning;and(iv)the

appropriate selection

#;;;*"ion

oJ thefarning

guides. These kinds of measures seem to

offer

some foundationsupon

which

,vorkplacJscan

becomeeffective

sites

for

thedevelopmentoftheti,'o,,ofknowleclc"thutwoulclbencfitbothworkplngg5nndthe

individuals who work in them'

Br

Learning at Work

I]

REnnRnxcns

BernhardtA(1999)Thelutureoflow-wagejobs:CaseStudiesinrhererailindustry. Insritute of Educatictn and the Economy Working paper No 10 March 1999.

Rernhardt, A., Morris, M., Handcock, M.,

&

Scott,M.

(1998).lrork

ond opportunie in thepost-indtrstrial labor market (No.

IEE Brief

No.

l9):

Institute on Education and the

Economy-Bierema,

L.L.

(2001). Women,Work,

and Learning.In

T

Fenwick (Ed.) .gocioc ultural perspectives on learning through work san Francisco: Josscv BassAViley.Billett

S&

Hayes S (2000) Meeting the demand; The needs o.f vocotional education andtraining clients. Adelaide NCVER. ISBN 0 87397 589 8.

Billett

S (2003) Sociogeneses, activity and ontogeny. Cuhure and Psychologt, vol 9 no 2.pp.i 33- r 69.

Billett S

(2002) Workplace pedagogic practices: Co-parlicipation and learning. BritishJournal of Educational Studies, vol 50, no 4 pp.457 -481 .

Riilett S. R. (200ia) Learning in the workplace: Strategies./br elfective practice. Allen ancl Unwin, Sydney.

Billett

S (2001b) Co-participation at work: Affordance and engagement.In

T Fenwick (Ed.)Sociocttltural perspectives

on

lectrning through worfr. New Directionsin

Adult

andContinuing Education Volume 92. San Francisco: Jossey Bass/Wiley. ISBN 0

78lg

51163.

Biilett, S (1999a) Guided leaming in the workplace.ln D Bouri & J Garick (Eds) {Lnderstanrling Learning at Work. London: Routledge.

Billen

S

(1999b)Work

as social practice: Activities and InterdependenciesJth

AnntralInternational

Conferenceon

Post-compulsory Educationand

Training,

ChangingPractice through research: Changing research through

practice, vol

2

pp128-138. Surfers Paradise Park Royal, Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia, 6-8 Dccember

1999.Billett,

S

(1995) Skill formationin

three central Queensland coal mines: Reflections onimplementation and prospects

for

the future. Cenlrefor

Research into Employment andWork, Griffi th University Brisbane, Australia.

Billett S (1994) Situated Leaming

-

a workplace experience. Australian Journal of Adylt and Ctininutity Educatiort, vol 3.1, no 2, pp. 112-130.Billett

S, BarkerM &

Hernon-TinningB

(2004) Participatory practices at work. pectagogl,,Culture and Society vol 72, no 2, pp. 233-251 .

Billett, S' McCann,

A

&

Scotl,K

(1998) Workplace mentoring: Organising ancl managi4g elfective practice. Centrefor

Learning and Work Research,Griffith

Universiry. ISBl,i 0868519149.Brunello, G.,

&

Medio, A. (2001). An explanation of International Differences in Education and workplace Training. European Economic Review, vol 45, no 2, pp. 307-322.Danford,

A

(1998) Teamworking and labour re-eulationin

the autocomponents industry. ll/ork, Emplo1:ment & Society vol 12, no 3, pp.409-431.Darrah' C. (1997) Complicating the concept of skill requirements: Scenes from a workplace

In

G.Hull

(Ed) Changing work, Chctnging workers: Critical perspectives on longtrage,t3 Stcphcn Billctt

Darrah, C.N. (1996) Leorning antl work:

An

erplorationin

Industrial Ethnography' Netv York: Garland Publishing.Engestrom,

Y

&

Miclclleton,D

(1996) Itttrocluctioti: Studying work as mindfirl practice' In Y Engestrom&

D.

Middleton (Eds.). Cognition and communicationat

I4/ork' cambridge: Cambridge tJniversiry Press' pp.1 -1 5'Ericsson,

K

A.,

&

LehmannA

C

(1996) Expert and erceptional performance: Evidenceof

maximal adaptation to task constraints. Annuctl Review of Psychology,4T , pp.213-305 'Goodnow, J. J. (1990) The socialisation of cognition: whats involved?' In J'

W''

Stigler, R' A'Shr.vetler

&

G. Herdt. (Eds).Aitut'al

Psvcholog.v- Carnbridge: Cambridge Univcrsity Prcss,pp. 259-86

Groot,

W.,

Hartog,J.,

&

Oosterbeek,H.

(1994). Costs and revenuesol

tnvestment ln Enterprise-Related Schooling. . oxforct Economic Papers, vol 46, no 4' pp'658-676' Hodges,D.

c.

(1998) Participation as dis-identiflcation witlr/in a communityof

practice'Mind' Culrure ctnd Acrivitl" 5(4) 272-290'

Hull, G. (lggl)Preface and Introduction In (G. Hull (Ed) changing work, Changingworkers:

critical

perspectives on lctngttage, literacy ancl skills. Ner'vYork,

State Universityof

Nerv York Press.

Hutchins, E. (1991) The social organization of tiistributed cognition' In

L'

B'

Resnick, J' M' Levine&

S. D. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognitiort' Washington DC: American Psychological Association, pp'283-307'lave-

J

(19S3) The practiceof

leaming.In

S

Chaiklin& J

Lave(Fds)

[-lndergtonding practice; Per,spectit,es on agtivitv ond contett Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press,pp.3-32.

La'c,

J. (1990) The culfure of acqriisition and the practice of understanding' In J'\\r'

Stigler'R.A. Shweder.,

&

G" Hcrdt (Eds.), Cttlrtn'al Psychologi cambridgc: cambridge UniversityPress, pp. 259-86.

Lave, J, & Wenger, E. ( 1 99 1 ) Sihtated leaming - legitimate peripheral participalion' Cambridge:

Cambridge UniversifY Press.

Leonteyev,

AN.

(1981) Prohtemsof

the Developmentof

theMind'

Progress Publishers, Moscow.Piaget,J(1966)Psycholog.yoJlntelligence'Totowa,NJ:Littlefield'Adam&Co'

Rogoff.

B.

(1995)'Observing

sociocultr-rral activitieson

three

planes: participatoryappropriation, gu.ided appropriation and apprenticeship', Sociocultural studies of the mind in J.v. werrsch, P. Dcl Rio

&

A. Alvcrez (Eils), Cambridge university Press' cambridge,pp.139-

164.Rogoff,

B

(i990) Apprenticeshipin

thinking-

cctgnilive development in sociul crtntext'llew

York: Oxford UniversitY Press"Solomon, N. (1999) Culture and diflerence in workplace leaming' In D Boud &

D"I'

Garrick' (Eds.) Uncler"stantling Leatning at llrcn'k London: Routlcdgc' pp' I 19- I 31'Tam, M (1991) Part-time Emplovment: A briclge ot a trop? Aldershot: Brookfield' uSA, wertsch, J

w

(1998) L{ind as action- oxford University Press. Nelv York.Thanii relcrred t.,

National T