Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1350

–

1800

This book presents extensive new research findings on and new thinking about Southeast Asia in this interesting, richly diverse, but much understudied period. It examines the wide and well-developed trading networks, explores the different kinds of regimes and the nature of power and security, considers urban growth, international relations and the beginnings of European involve-ment with the region, and discusses religious factors, in particular the spread and impact of Christianity. One key theme of the book is the consideration of how well-developed Southeast Asia was before the onset of European involve-ment, and, how, during the peak of the commercial boom in the 1500s and 1600s, many polities in Southeast Asia were not far behind Europe in terms of socio-economic progress and attainments.

Ooi Keat Gin is Professor of History at Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia.

Routledge Studies in the Modern History of Asia

1. The Police in Occupation Japan Control, corruption and resistance

3. The Aftermath of Partition in South Asia

5. Japan and Singapore in the World Economy

Japan’s economic advance into Singapore, 1870–1965

8. Religion and Nationalism in India The case of the Punjab

Harnik Deol

9. Japanese Industrialisation Historical and cultural perspectives Ian Inkster

10. War and Nationalism in China 1925–1945

12. Japan’s Postwar Economic

Recovery and Anglo-Japanese Relations, 1948–1962

Noriko Yokoi

18. The United States and

22. The Rise and Decline of Thai Absolutism

25. The British Empire and Tibet 1900–1922

Wendy Palace

26. Nationalism in Southeast Asia

If the people are with us Nicholas Tarling

27. Women, Work and the Japanese Economic Miracle

The case of the cotton textile industry, 1945–1975

Helen Macnaughtan

28. A Colonial Economy in Crisis Burma’s rice cultivators and the world depression of the 1930s Ian Brown

29. A Vietnamese Royal Exile in Japan

Prince Cuong De (1882–1951) Tran My-Van

From the nineteenth century to the Pacific War

36. Britain’s Imperial Cornerstone

The rise of French rule and the life of Thomas Caraman,

42. Beijing–A Concise History Stephen G. Haw

45. India’s Princely States People, princes and colonialism

49. Japanese Diplomacy in the 1950s From isolation to integration Edited by Iokibe Makoto,

Caroline Rose, Tomaru Junko and John Weste

50. The Limits of British Colonial Control in South Asia

Spaces of disorder in the Indian Ocean region

Edited by Ashwini Tambe and Harald Fischer-Tiné

53. Communist Indochina R. B. Smith, edited by Beryl Williams

54. Port Cities in Asia and Europe Edited by Arndt Graf and

Chua Beng Huat

55. Moscow and the Emergence of Communist Power in

China, 1925–30

The Nanchang Rising and the birth of the Red Army

58. Provincial Life and the Military in Imperial Japan

61. The Cold War and National Assertion in Southeast Asia Lubis (1922–2004) as editor and author

66. National Pasts in Europe and East Asia

P. W. Preston

67. Modern China’s Ethnic Frontiers A journey to the West

Hsiao-ting Lin

68. New Perspectives on the History and Historiography of Southeast Asia Continuing explorations

Michael Aung-Thwin and Kenneth R. Hall

69. Food Culture in Colonial Asia A taste of empire

Cecilia Leong-Salobir

70. China’s Political Economy in

Modern Times

71. Science, Public Health and the

Edited by Michael S. Dodson and Brian A. Hatcher

75. The Evolution of the Japanese Developmental State

Institutions locked in by ideas Hironori Sasada

76. Status and Security in Southeast Asian States

79. China and Japan in the Russian Imagination, 1685–1922

To the ends of the Orient Susanna Soojung Lim

80. Chinese Complaint Systems Natural resistance

Qiang Fang

81. Martial Arts and the Body Politic in Meiji Japan

83. Post-War Borneo, 1945–1950 Nationalism, Empire

and state-building Ooi Keat Gin

84. China and the First Vietnam War, 1947–54

Laura M. Calkins

85. The Jesuit Missions to China and Peru, 1570–1610

Ana Carolina Hosne

86. Macao–Cultural

Interaction and

Literary Representations Edited by Katrine K. Wong and C. X. George Wei

87. Macao–The Formation of a

Global City

Edited by C. X. George Wei

90. Transcultural Encounters between Germany and India Kindred spirits in the 19th and 20th centuries

A reading, with commentary, of the complete texts of the Kyoto School discussions of“The Standpoint of World History and Japan” David Williams

92. A History of Alcohol and Drugs in Modern South Asia

Intoxicating affairs

Edited by Harald Fischer- Tiné and Jana Tschurenev

93. Military Force and Elite Power in the Formation of Modern China Edward A. McCord

94. Japan’s Household Registration

System and Citizenship Koseki, identification and documentation

Edited by David Chapman and Karl Jakob Krogness

95. Ito- Hirobumi– Japan’s First

Prime Minister and Father of the Meiji Constitution

Fischer-Tiné, and Nada Boškovska

97. The Transformation of the

98. Xinjiang and the Expansion of Chinese Communist Power

102. Malaysia’s Defeat of

Armed Communism

The second emergency, 1968–1989 Ong Weichong

103. Cultural Encounters and Homoeroticism in Sri Lanka Sex and serendipity

104. Mobilizing Shanghai Youth CCP internationalism,

GMD nationalism and Japanese collaboration Kristin Mulready-Stone

105. Voices from the Shifting Russo-Japanese Border Karafuto / Sakhalin

Edited by Svetlana Paichadze and Philip A. Seaton

106. International Competition in China, 1899–1991

The rise, fall, and restoration of the Open Door Policy

Bruce A. Elleman

107. The Post-war Roots of Japanese Political Malaise Dagfinn Gatu

108. Britain and China, 1840–1970 Empire,finance and war Edited by Robert Bickers and Jonathan Howlett

109. Local History and War Memories in Hokkaido Edited by Philip A. Seaton

110. Thailand in the Cold War Matthew Phillips

111. Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1350–1800

Early Modern Southeast

Asia, 1350

–

1800

Edited by

First published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

© 2016 Ooi Keat Gin and Hoàng Anh Tuấn

The right of Ooi Keat Gin and Hoàng Anh Tuấn to be identified as the authors of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Early modern Southeast Asia, 1350-1800/editors, Ooi Keat Gin, Hoàng Anh Tuấn.

pages cm. -- (Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia; 111) Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Southeast Asia--History. I. Ooi, Keat Gin, 1959- editor. II. Hoàng, Anh Tuấn, editor. III. Tarling, Nicholas. Status and security in early Southeast Asian state systems. Container of (work):

DS526.3.E35 2016 959--dc23

2015015007

ISBN: 978-1-138-83875-8 (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-73384-5 (ebk)

To

Emeritus Professor Nicholas Tarling

Scholar par excellence

,

Contents

List of illustrations xvi

List of contributors xvii

Foreword xx

Preface xxii

Acknowledgement xxv

Abbreviations and Acronyms xxvii

Introduction 1

PART I

Diplomatic and inter-state relations

11

1 Status and security in early Southeast Asian state systems 13 NICHOLAS TARLING

2 The“Alexandrowicz Thesis”revisited: Hugo Grotius, divisible sovereignty, and private avengers within the Indian

Ocean World System 28

ERIC WILSON

3 ThePhrakhlangMinistry of Ayutthaya: Siamese instrument to

cope with the early modern world 55

BHAWAN RUANGSILP

PART II

Interactions and transactions

67

4 Applying the seas perspective in the study of eastern Indonesia in

the early modern period 69

5 Borneo in the early modern period:c. late fourteenth toc. late

eighteenth centuries 88

OOI KEAT GIN

6 Another past: early modern Vietnamese commodity expansion

in global perspective 103

HOÀNG ANH TUẤN

7 VânĐồn: an international sea port ofĐại Việt 122

NGUYEN VAN KIM

8 Batu Sawar Johor: a regional centre of trade in the early

seventeenth century 136

PETER BORSCHBERG

9 Urban growth and municipal development of

early Penang 154

NORDIN HUSSIN

PART III

Kingship and state systems

173

10 Revisiting“kingship” in seventeenth-century Aceh: fromira et

malevolentiatopax et custodia 175

SHER BANU A.L. KHAN

11 Catching and selling elephants: trade and tradition in seventeenth

century Siam 192

DHIRAVAT NA POMBEJRA

12 Cham–Viet relations in Bình Thuận and Ninh Thuận under Nguyễn rule from the late seventeenth century to

mid-eighteenth century 210

DANNY WONG TZE KEN

PART IV

Indigenizing Christianity

231

13 The glocalization of Christianity in early modern

Southeast Asia 233

14 The passing of rice spirits: cosmology, technology, and gender

relations in the colonial Philippines 250

FILOMENO V. AGUILAR JR.

Glossary 266

Bibliography 269

Index 297

List of illustrations

Figures

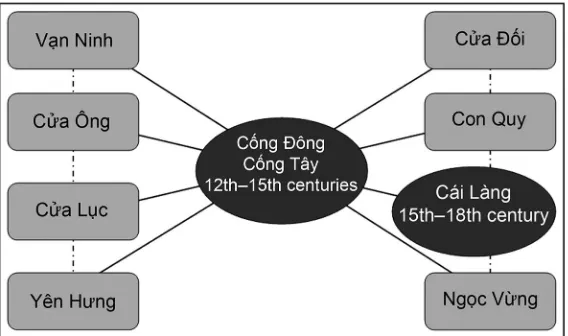

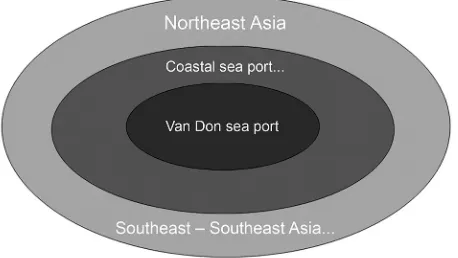

6.1 “Globalizing” the Vietnamese economy,c. 1600s 109

7.1 Vân Đồn seaport system 129

7.2 Van Don seaport and its relations with international

trading network 131

Maps

4.1 Island world of Southeast Asia 71

4.2 Eastern Indonesia 73

4.3 Timor 74

7.1 Main islands of Vân Đồn 128

8.1 Johor Empire 137

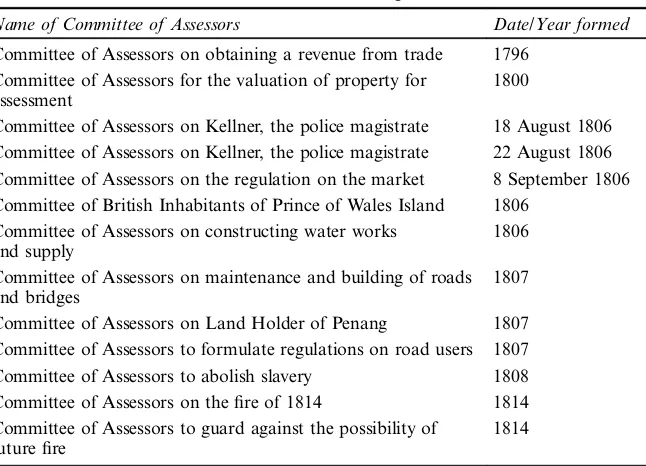

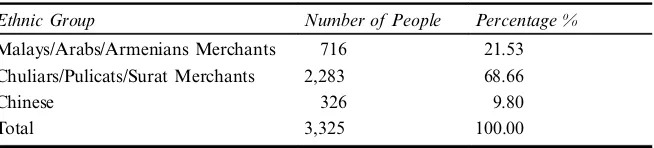

Tables

9.1 Committees of Assessors formed in Penang 1796–1814 158 9.2 Number of houses in Penang destroyed in the 1814 fire 164 9.3 Number of people inhabiting the houses/shops destroyed in the

1814fire 164

List of contributors

Filomeno V. Aguilar, Jr.is Professor of History and Dean of the School of Social Sciences, Ateneo de Manila University. He is the editor ofPhilippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints, and is the author of Migration Revolution: Philippine Nationhood and Class Relations in a Globalized Age(2014).

Barbara Watson Andaya is Professor of Asian Studies at the University of Hawai‘i at Ma-noa. Her specific area of expertise is the western Malay-Indonesia archipelago. Her primary publications arePerak, The Abode of Grace: A Study of an Eighteenth Century Malay State (1979); two co-authored books, theTuhfat al-Nafis, a translation of a nineteenth-century Malay text (1982) and A History of Malaysia (1982, rev. ed., 2000); To Live as Brothers: Southeast Sumatra in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (1993); The Flaming Womb: Repositioning Women in Southeast Asian History, 1500–1800(2006). Her current project is a history of religious interaction in Southeast Asia, 1511–1800.

Leonard Y. Andayais Professor of Southeast Asian history at the University of Hawai‘i at Ma-noa in Honolulu. His area of specialization is the early modern history of Southeast Asia with research interests in the early modern period of the Malay-Indonesian archipelago. He has published books on the history of Johor (1975), South Sulawesi (1982), Maluku (1993), and the Straits of Melaka (2008), and has co-authored with Barbara Watson Andaya, A History of Malaysia (1982, rev. ed. 2001), and A History of Early Modern South-east Asia, 1400–1830 (2015). His current research project is a study of eastern Indonesia in the early modern period through an examination of its interlocking economic, social, and ritual networks.

Peter Borschberg is Associate Professor at the Department of History, National University of Singapore. He is chiefly interested in the historic origins of international law, maritime history and the history of Asian-European trade in the early modern period, as well as pre-Raffles Singa-pore and Riau. His recent books are The Singapore and Melaka Straits (2009), and Hugo Grotius, the Portuguese, and Free Trade in the East Indies(2011).

Dhiravat na Pombejraobtained his doctoral degree in history at University of London and taught history at Chulalongkorn University for many years until his retirement. His research focused on political and economic history of early modern Thailand. His recent publications (as co-editors) includeVan Vliet’s Siam(2005), andThe English Factory in Siam, 1612–1685(2007).

Hoàng Anh Tuấn obtained his doctorate from Leiden University, and is Associate Professor at the Department of History, Vietnam National University, Hanoi, Vietnam. He is the author of Silk for Silver: Dutch– Vietnamese Relations, 1637–1700 (2007), and coordinator of several inter-national projects. His current main teaching and research interestsinter alia early modern Asian–European interactions, early-modern globalization and the integration of Vietnam.

Sher Banu A. L. Khan obtained her PhD from Queen Mary, University of London and is currently Assistant Professor at the Department of Malay Studies, National University of Singapore. Her research interests include female leadership and gender studies, Islam and Globalization.

Nguyen Van Kimis Associate Professor of history at Vietnam National Uni-versity, Hanoi. His research interests include early modern Vietnamese and Japanese history, and maritime history. He has published a number of books in Vietnamese and articles in both Vietnamese and English. His recent works areNgười Việt với biển (2011) and Việt Nam trong thếgiới Đông Á(2011).

Nordin Hussinis Professor of social and economic history and Head for the Centre for History, Politics and Strategic Studies, Faculty of Social Sci-ences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi. His main research areas are mostly on the early modern period of Southeast Asian history with major works published by NIAS Press and NUS Press. Cur-rently he is working on a Malay text“Sedjarah Riau dan Jajahan Taklo-knya”, a Malay manuscript regarding the presence of Bugis princes in the royal court of the Johore kingdom, and continues with the social and eco-nomic history of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Dutch in Melaka based on the Weeskamer collections from the Orphan Chamber of Dutch Melaka.

edited Themes for Thought on Southeast Asia: A Festschrift to Emeritus Professor Nicholas Tarling on the Occasion of His 75th Birthday. New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, 11, 1 (June 2009): 1–446. Recent pub-lications include The Japanese Occupation of Borneo, 1941–1945 (2011), andPost-war Borneo: Nationalism, Empire, and State-building, 1945–1950 (2013). A Fellow of the Royal Historical Society (London), he is editor-in-chief of theInternational Journal of Asia Pacific Studies(IJAPS) (www.usm. my/ijaps/) as well as series editor of the APRU-USM Asia Pacific Studies Publications Series (AAPSPS).

Nicholas Tarling is Fellow and Emeritus Professor of History at the New Zealand Asia Institute, University of Auckland. He has also been Visiting Professor at Universiti Brunei Darussalam and Honorary Professor at the University of Hull. Most of his work has been on the history of Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and Burma in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and in particular on British policy in and toward those countries. His most recent books includeRegionalism in Southeast Asia(2006), andBritain and the West New Guinea Dispute(2008).

Eric Wilson is a senior lecturer of law at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. In 1991 he completed his doctorate in the history of early modern Europe under the supervision of Robert Scribner. In 2005 he received the degree of Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) from the University of Melbourne. He is the author of The Savage Republic: De Indis of Hugo Grotius, Republicanism, and Dutch Hegemony in the Early Modern World System (c. 1600–1619)(2008). He is the editor of a series of works on critical criminology, viz. Government of the Shadows: Parapolitics and Criminal Sovereignty (2009); The Dual State: Parapolitics, Carl Schmitt and the National Security State Complex(2012). The third volume which is a study of the covert origins and dimensions of the French and American wars in Vietnam is currently under preparation. His research interests include the history of comparative law of Southeast Asia, critical jurisprudence, the history and philosophy of international law, and critical criminology.

Danny Wong Tze Ken is Professor of history at the Department of History, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Malaya where he teaches history of Indochina and Southeast Asia. His research interests include history of Champa, Sabah, and the Chinese in Malaysia. Amongst his publications are: Historical Sabah: The War (2010) and The Nguyen and Champa during 17th and 18th Century (2007) Historical Sabah: Community and Society(2004); The Transformation of an Immigrant Society: A Study of the Chinese of Sabah (1998); and Vietnam-Malaysia Relations during the Cold War(1995).

Foreword

It is a pleasure to welcome this collection of essays, for at least three reasons. Firstly, the volume consolidates the recognition of Early Modernity as a meaningful way to define a global moment in which Southeast Asia played a particularly central role. The Early Modern period began with the“long six-teenth century”that unified the world, and petered out in the late seventeenth or eighteenth. There was no such category when those of my generation learned our history. The pattern of dividing European history into Medieval, Renaissance and Modern was assumed to be normative, and the majority of the world for which this made little sense nevertheless found itself categorized according to this established scheme. The importance of the long sixteenth century– roughly 1490–1630– as the phase when the peoples of our planet were brought into constant contact and interaction with one another was recognized if at all by terms such as“Age of Discovery” or“Vasco da Gama Epoch”, which implied a European vantage point. Early Modern History brought a refreshing opportunity to perceive this period as a genuinely global phenomenon, when people, goods, ideas, crops, technologies, and diseases from opposite sides of the world collided and interacted, initially with eager curiosity, but ultimately with some much less agreeable results.

generation passed from the scene, there had been a regrettable tendency for Southeast Asians to focus their attention on recent history where the language and conceptual demands were lowest, leaving the earlier history more than ever to foreigners. Here, however, Bhawan Ruangsilp from Thailand, Hoàng Anh Tuấn from Viet Nam, and Sher Banu from Singapore all show a mastery of the difficult Dutch sources which provide an unrivalled data set for the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Given added confidence by the training of the TANAP program in Leiden in reading these documents, they have been able to advance our knowledge of the nature of trade and statecraft throughout the region. Malaysian Danny Wong, meanwhile, is not afraid to move into difficult Vietnamese and Cham sources to expand our understanding of the last phase of the Cham polity.

Barbara and Leonard Andaya, Nicholas Tarling, and Dhiravat na Pombejra are distinguished representatives of an earlier generation that can be said to have pioneered the conceptualization of Early Modern History, at a time when it was far from established as either a phrase or a concept. Nicholas Tarling deserves special tribute for inspiring and funding a series of conferences designed explicitly to facilitate this transition to a new generation. This book is afine example of how that process is working.

Finally, the papers show commendable innovation in exploring new front-iers many of which will give food for thought for all those that follow. In discussing Hugo Grotius, Eric Wilson shows the centrality of Southeast Asian experience in the creation of Early Modern ideas– indeed in laying some of the foundations of our nation-state system. Barbara Andaya shows similarly how the globalization of religion was an essential part of early modernity, with Catholic Christianity and Sunni Islam both being transformed by a global contest. Other frontiers are crossed here in economic history work, the environment (Dhiravat) and conceptualization. The baton of explicating Southeast Asia’s remarkable gender pattern, long carried by Barbara Andaya, has deftly been passed to Filomena Aguilar and Sher Banu, each exploring a critical dimension of Early Modern change from a gender perspective. Southeast Asia’s unusually long experience with a relatively balanced gender pattern should give confidence and inspiration to all of us as we live through an era of experimentation in that direction.

Preface

A journey of sorts describes this current undertaking of an edited volume that had a long gestation period. The seed of an idea was conceptualized back in 2011 over a course of two “serious” days of deliberations, arguments, and camaraderie, and a“joyful”day of outdoor excursion and appreciation of the Vietnamese environment, culture, history, and heritage, and also the warm hospitality. This Hanoi conference upon reflection was indeed a fruitful outing. But it was a protracted journey with many delays from the last farewell to the concretization of a proposal for a volume. Alas, clear-cut plans were underway following months of uncertainties and the pendulum of optimism swung favourably in the shaping of the volume. Ambitious or plain greed, attempts were made to gather as many offspring as possible; finally fourteen survived through the journey.

The Nicholas Tarling Conference on Southeast Asian Studies was conceived in 2006 following the celebration of Emeritus Professor Nicholas Tarling’s 75th year in Auckland, New Zealand. The original idea found sustenance andfinally realized in 2009 in Singapore when the inaugural conference was held “to advance the study of Southeast Asia primarily from an historical perspec-tive”.1 The conference theme then was Southeast Asia and the Cold War. The inaugural volume of the same name was published by Routledge in 2012 undertaken by Albert Lau (National University of Singapore) who had organized the Singapore conference. As agreed, the second outing was on the region’s mainland with Hanoi the choice and Hoàng Anh Tuấn (Vietnam National University) assuming the role of organizer.

period of the region’s historical development. Complementing territorial-based works were studies that transcend natural and manmade political divides to cover wide areas of the region. The intellectual discourse borne from the conference proceedings undoubtedly extended the boundaries of our appre-ciation and understanding of past developments that undoubtedly had a hand in shaping contemporary Southeast Asia.

Professor Tarling himself bore witness to the Hanoi get-together, and undoubtedly was delighted with this second outing. The working papers pre-sented were diverse in content, challenging if not intriguing in some cases, but all tied-on the thread of the conference theme “Between Classical and Modern: Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Period,c.late 14th to late 18th centuries”. As expected Hoàng as conference organizer took on the role as editor of the second volume. But owing to various circumstances a joint effort of editing was undertaken by both Hoàng and Ooi Keat Gin.

Drawn from this aforesaid proceedings is this present edited volume compris-ing a collection of essays borne from the revised (and expanded) conference working papers that is intended to share, add, and contribute further to the greater understanding of Southeast Asia during this pivotal period of its history. The late fourteenth to late eighteenth centuries was the period prior to the onset of major and radical changes wrought by the increasing presence and direct and active participation of Western imperial and colonial powers from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

From the submitted revised working papers, there are fourteen works (hence fourteen chapters) organized along the lines of four themes:“diplomatic and inter-state relations” (Chapters 1 to 3); “interactions and transactions” (Chapters 4 to 9); “kingships and state systems” (Chapters 10 to 12); and, “indigenizing Christianity” (Chapters 13 and 14). The volume opens with an “Introduction”that basically provides an overall background of the scholarship on the early modern period of Southeast Asia. At the same time it contextualizes the corpus of works and draws out their significance and contributions to the volume as a whole.

the conference and this present volume succeeded in contributing to the sustainability to the study of the early modern period in Southeast Asia.

Ooi Keat Gin Hoàng Anh Tuấn

Note

1 Ooi Keat Gin,“Nicholas Tarling Conferences on Southeast Asian Studies Guidelines”, (2001): 1.

Acknowledgement

“No man is an island”, likewise no enterprise was singularly executed and accomplished. Numerous persons were directly and indirectly involved in producing an edited volume, and the present outcome affirmed the norm. We, as joint editors, wish to extend our appreciation to all involved professionally as contributors and publisher. We expressed our gratitude to the Nicholas Tarling Foundation in partnership with the College of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University, Hanoi in organizing and hosting The Second Nicholas Tarling Conference on Southeast Asian Studies, 3–4 November 2011 from which the contents of this present volume is drawn. Hoàng Anh Tuấn donned many hats throughout this protracted undertaking, initially as conference host and organizer, then assuming as tour leader and guide during the one-day excursion for participants, andfinally as co-editor of this volume. In all capacities, despite trying circumstances from within and without, Hoàng managed to excel and deliver what was expected of him in the various roles he was entrusted with.

All the contributors to this volume exhibited much patience especially during the early stages of this undertaking, and towards the closing several months demonstrated professionalism, diligence, cooperation, and again patience in adhering to technical requirements, inquiries, feedbacks, and deadlines. Grate-fully we thanked Peter Sowden, the commissioning editor at Routledge, who took on this edited volume, and tolerated with aplomb the extended delays. Also to Routledge’s anonymous specialist reviewer whose comments, suggestions, and criticisms helped improved and reshaped the original proposal to the present form.

We wish to thank Emeritus Professor Anthony Reid for his Foreword that succinctly contextualizes the volume in the wider scholarship and historiography of the early modern period of Southeast Asia.

Malaysia, the home institution of Professor Ooi in granting him leave of absence during semester for this Hanoi assignment.

An accolade of thanks to all individuals and institutions that in one way or another had contributed in realizing the completion of this edited volume.

Lastly, but undoubtedly not the least, both our families’ forbearance is a testament to the bonds of love that we share: Swee Im; Ling, Pham, and Tieuw.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

ASEAN Association of South-East Asian Nations

BEFEO Le Bulletin de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient (Bulletin of the French School of the Far East)

BKI Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia)

EEIC English East India Company IR International Relations

ISEAS Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore

JIA Journal of Indian Archipelago / JIAEA Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia

JMBRAS Journal of the Malayan/Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society

JSBRAS Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society JSEAS Journal of Southeast Asian Studies

KIT Royal Tropical Institute (Koninklijk Instituut voor de Tropen), Amsterdam, The Netherlands

KITLV Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies), Leiden, The Netherlands

NIAS Nordic Institute of Asian Studies, Copenhagen, Denmark

NTT Nusa Tenggara Timur

NUS National University of Singapore, Singapore

RAC-CSA Royal Archives of Champa, Société Asiatique, Paris, France SEAP Southeast Asia Program

Introduction

But whatever decision is made regarding terminology, scholarship on Southeast Asia is increasingly viewing a period that stretches from about thefifteenth to the early nineteenth century as rather different from those traditionally described as “classical”and“colonial/modern”. The term“early modern”[by] itself is at pre-sent a convenient tool for historical reference, and only time will tell whether it will find general acceptance.1

By the dawn of the second decade of the twenty-first century, Southeast Asia as a region has undergone a relatively long phase of study in which both dimensions of place and time gained adequate scholarly consideration. For readers of Southeast Asian studies, the 1940s was a significant starting point. Since the publication of Georges Coedès’ Histoire ancienne des états hin-douisés d’Extrême-Orient2in 1944, the history of a region which would later be terminologically coined as Southeast Asia gained increasing attention from various groups of scholars, especially historians.

In the early days of the voyage of this terminology, the geographical con-fine has been relatively changeable,3 whilst its time frame was also variable adequately.4 As a region, contemporary conceptualized Southeast Asia is a highly distinct place, totally different from the others, for instance, the Indian subcontinent and the“sinicized world”of Northeast Asia. And centuries before that, the people of Southeast Asia already identified its region clearly as“below the wind”in order to distinguish themselves from those coming from the other lands such as India and China.5In this self-distinct region of Southeast Asia,

empires most notably Funan,Śrīvijaya, Angkor, Champa. Toward the northern

part of the region, the Vietnamese kingdom of Đại Việt was a rare case in

which, despite“rooted in Southeast Asia”,7the process of nation-state deve-lopment and acculturation was significantly influenced by the Chinese culture and civilization.

It is more problematic, however, when one turns to the issue of time frame. For long, the history of Southeast Asia was commonly viewed as a relatively even evolution from “pre- and pro-history” through the “early societies” characterized by the combination of indigenous characteristics and Indian influences, the “classical period” which witnessed significant socio-economic transition before enduring the“colonial age” from the latter half of the eight-eenth century. Yet, the transition of the region from “classical” to “modern”, between c. mid fourteenth to late eighteenth centuries, requires in-depth elaboration, considering the profound internal development (consolidation of states and social systems, development of new trading networks, religious thought, etc.) as well as the global transformation (encounters, rivalries and conflicts with, besides the aged-old Indian and Chinese factors, Western powers, that is the European East India companies and Christian missionaries). This makes the period betweenc.1350 andc.1800 a distinct era, increasingly accepted today amongst scholars as the“early modern period”in Southeast Asian history. Yet before introducing the issues from which this monograph is formed, it is of essentiality to recapitulate the academic assessment of“early modern”in Southeast Asian historiography during the past half century. Emerged in Europe during the 1940s,“early modern” was increasingly used to indicate a period of spectacular socio-economic transformation in Europe fromc.1500 toc.1800. Besides the rapid expansion of long-distance trade after the great geographical discoveries by the Iberians, Europe also witnessed a series of internal changes, notably the emergence of absolutist powers and nation-states.8 During the 1970s, the concept of “early modern” was increasingly

used by European historians, namely the English, German, and Dutch. Together with the popular use of “early modern”, the “modern period” was also re-set to begin after the French revolution or from the Industrial revolution in England.9

considered had begun about five hundred years earlier, commencing a new historical phase during the fifteenth century.11 In short, the mid- fourteenth/ earlyfifteenth century marked a significant transition in Southeast Asia when socio-economic transformations took place spurred by developments from within and pushes from without, viz. the expansion of trade networks based on Muslim mercantile patterns, and the initial phase of European penetration during the latter part of the century. During the heyday of commercial boom, c. 1500s and 1600s, many polities in Southeast Asia were far from behind Europe in terms of socio-economic progress and attainments, before descending from the late seventeenth century into the so-called“underdevelopment”.12

At the other phase of the continuum, the mid-eighteenth century to early nineteenth century was often regarded as the appropriate turning point. In his immense work, D.G.E. Hall considered the period of European territorial expansion during the latter part of the eighteenth century as a significant turning point in the regional history.13In the early 1970s, the mid- eighteenth century was

unanimously agreed upon as the date of change to modern times in Southeast Asia, “when Europeans in the region first had the power and inclination to impose on others their technical skills and new world view”.14It is obvious that, the four hundred-year period falling between the “Indian period” and the “modern era”was increasingly aware among the scholarly community as a dis-tinctive phase, yet still generally classified as the“pre-colonial”.15 When The Cambridge History of Southeast Asiawas published in 1992, the authors of“Part Two (Fromc.1500 toc.1800 CE)”regarded the period from the latefifteenth century to the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century as a distinct episode in the history of the region. During this period, alongside the age-old non-indigenous factors, that is the Indian and the Chinese was the formidable arrival of the Europeans. These new actors, without a doubt, contributed to influence the development of Southeast Asian states in one way or another, from socio-economic to political, cultural and religious changes.16

It was not until the early 1990s that the periodization of Southeast Asian history attained a breathtaking progress. Developing from a conference sponsored by the Joint Committee on Southeast Asian Studies and the American Council of Learned Societies in 1989, an edited volume by Anthony Reid was published in 1993 titledSoutheast Asia in the Early Modern Era: Trade, Power, and Belief.17

The official use of the explicit term of“early modern” was of significance as it reflected“the growth since the 1970s in relevant local and regional studies that has expanded knowledge in historical developments”.18 Since then, the early modern period in Southeast Asian history became an exciting phase, though with controversies, thus required substantial revisionist research.19 In their textbook,

Barbara Watson Andaya and Leonard Y. Andaya regard the period from 1400 to 1830 as the “early modern” period in the history of Southeast Asia with various sub-periodization such as “beginning of the early modern era” (1400–1511), acceleration of change (1511–1600), “expanding global links and their impact on Southeast Asia” (1600–1690s), “new boundaries and changing regimes” (1690s–1780s), and “the last phase” (1780s–1830s).20

Currently in the mid-2010s, it is largely acknowledged that the early modern period was a watershed in human history. As for Southeast Asia, the region played a critical role in global trade between thefifteenth century and seventeenth century whereas the global commercial expansion during the long “sixteenth century” affected this region immediately and profoundly. In this process of global interactions, the European was often over-emphasized and centered at the heart of the play. It is, however, rightly argued that the evi-dences of development in Southeast Asia such as“the quickening of commerce, the monetization of transactions, the growth of cities, the accumulation of capital and the specialization of function which formed part of capitalist transition”, etc. have obviously begun in the region well before the European penetration into and influence upon the local societies in the early sixteenth century.21A recent analy-sis of the“early modern”Southeast Asian states further admitted that the term helped distinguish the “foundational states” – typically prospered before sig-nificant European impact–and the colonial-era polities which were profoundly influenced by the European and American.22

All in all, an understanding of the various aspects of Southeast Asia in the early modern period is a prerequisite to comprehending what the region had “lost” in the course of European intrusion and subsequent domination, local tradition overridden by Westernization and modernization, the twin jugger-nauts of “progress” and “development”portrayed as imperatives and“ must-haves”for the peoples and the territories of the region. In re-discovering what had been“lost”and the circumstances therein will reinforce the unique characteristics of the region and the identity of the people. On the basis of the papers available for this edited volume, four main themes of early modern Southeast Asia will be focused here: diplomatic and inter-state relations; interactions and transactions; kingship and state systems; and indigenizing Christianity.

Diplomatic and inter-state relations

towards the larger political groupings which were to form the bases of later nation-states”.23

The arrival of the Westerners from the latefifteenth century, nevertheless, contributed to the transformation of regional diplomacy and inter-state rela-tionship. Western technological advances in weaponry, for instance, was a double-edged sword, while it helped increased the power of native rulers, it also contributed to the subsequent demise of numerous indigenous polities in the region, especially in insular Southeast Asia.

The ongoing discourse of early modern Southeast Asian diplomatic and inter-state relations is highlighted through examining a number of case stu-dies. Nicholas Tarling utilizes thelong dureeperspective in exploring the state systems in Southeast Asia from early times to the contemporary nation-state (Chapter 1). Adopting a revisionist approach Eric Wilson discusses judicial issues in the Netherlands East Indies from the perspective of theVereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie(VOC, United [Dutch] United East India) between the sixteenth century and nineteenth century (Chapter 2). Utilizing Ayutthaya’s Phrakhlang Ministry (Ministry of External Relations and Maritime Trading Affairs) Bhawan Ruangsilp explores the manner and strategies employed by the Siamese in addressing diplomatic and inter-state relations during the early modern period (Chapter 3).

Interactions and transactions

Trade, maritime trade in particular, was highly developed in pre-modern Southeast Asia. This region itself was not only active in international trade with the existence of maritime power such as Srivijaya but also functioned as a rendezvous of different merchant groups from West Asia, South Asia, and East Asia. The development of cash crops in the early fifteenth century as well as the rising European demand for spices enabled the birth in the region of its “Age of Commerce”, a phrase coined by Anthony Reid, to a large extent transformed this region into a sort of“Asian Mediterranean”a model forged by Fernand Braudel and the Braudelian school.24Reid postulates that the“age of commerce”in Southeast Asia probably reached its zenith between 1570 and 1630 when abundantflows of silver poured into the region in exchange for an assortment of spices. Consequently this commercial expansion signi-ficantly transformed Southeast Asia not only in the economic arena as an important cog in the wheel of global trade but also in the socio-cultural sphere.25Yet, refuting Anthony Reid’s Age of Commerce thesis, Victor

as the Spanish control of Manila almost a century earlier), indigenous Southeast Asian trade gradually declined through the eighteenth century. Consequently weak states with less centralized politics and less prosperous populations faced the determined Western profit-fuelled juggernaut in the subsequent centuries with disastrous implications for the former.

Against this background of flourishing trade and commerce where there were extended and expanded interactions and transactions between the peo-ples of Southeast Asia and others beyond the region, six studies are presented. In opening this theme Leonard Y. Andaya demonstrates the interconnectedness of the“seas”that brings together the islands where he utilizes eastern Indonesia during the early modern period as an example of this vibrant phenomenon (Chapter 4). The push and pull factors from within and without the island of Borneo between the late fourteenth and late seventeenth centuries are analyzed by Ooi Keat Gin (Chapter 5). Vietnam’s role and dynamism during the early modern period is examined by Hoàng Anh Tuấn through the production and trading of export commodities (Chapter 6), and by Nguyen Van Kim of the port-polity of VânĐồn that had participated in international trade for more

than six centuries (Chapter 7). On the southern Malay Peninsula Peter Borsch-berg evaluates Batu Sawar in Johor as a commercial centre for regional trade in the seventeenth century (Chapter 8) while Nordin Hussin traces the early devel-opment (last quarter of the eighteenth century) of the port-polity of Penang off the Malay Peninsula’s northwest (Chapter 9).

Kingship and state systems

The trade whichflowed strongly to Southeast Asia during the “Age of Com-merce”brought by Muslim traders such as Arab, Persian and Indian merchants and thereafter Chinese traders followed by Europeans–Portuguese, Dutch and English–increased the region’s political, commercial and diplomatic contacts with Asia, Europe, Africa, and the New World. The burgeoning trade brought new kinds of luxuries and wealth as well as new varieties of ideas and faiths– new technologies in shipbuilding, gun-making, erection of forts, construction of palaces, and new perceptions of state and religious beliefs. Rulers of port-polities amassed wealth that was channeled to build armies, navies, and fortify their palaces thereby enabling them to gain the upper hand vis-à-vis their rivals, and increasingly dominated their hinterlands. Such developments were exemplified by the rise of powerful, absolutist rulers in the likes of Sultan Abulfatah Ageng of Banten, Sultan Iskandar Muda of Aceh, Sultan Agung of Java, and Sultan Babullah of Ternate.

common people (rakyat, subjects). Muslim international trading networks were used to increase the power, wealth and prestige of these rulers. Besides governance and state affairs Islamic ideas also found local expression in literature, the arts, theology, architecture, and law. The cosmopolitan Muslim ports of Aceh, Demak, Banten, and Gowa became large populous port-cities and dynamic cen-tres of opulent, creative urban culture. It was in these cencen-tres that foreign ideas, technologies, and fashions were imitated, adapted, or resisted. These ports basked in their heyday between 1500 and 1700; thereafter decline sets in due to instabilities from within and European competition from without.

The issues of kingship and state systems in early modern Southeast Asia has been under various discussions for decades. For long Anthony Reid’s “maritime economy” model has been influencing largely the regional scholar-ship on overall political transformation. Victor Lieberman, however, recently argues in his second volume ofStrange Parallels that the early arrival of the Europeans, in the sixteenth century, had a long-term effect similar to the con-quest of China, India and West Asia (Middle East) by Turkic and other Cen-tral Asian nomads;“‘white Inner Asians’ in [insular] Southeast Asia filled a role analogous to that of Manchus and Mughals in their respective spheres”.27 Entering these controversial debates, Sher Banu A. L. Khan argues the case of an alternative model of kingship where female ascendancy triumphed in the seventeenth century in the Islamic sultanate of Aceh Dar al-Salam (Chap-ter 10). Dhiravat na Pomberja deftly ties the royal elephant hunt to“classical” statecraft, and draws political implications in the commercial transactions of elephants in seventeenth and eighteenth century Ayutthaya (Chapter 11). Danny Wong Tze Ken utilizesfinancial, commercial, and economic-related documents from the Panduranga Archives to reconstruct Viet-Cham relations in Binh-Thuan during the period from the late seventeenth to eighteenth century (Chapter 12). All three case studies demonstrated the particularity, diversity and tenacity of Southeast Asian kingship and state systems during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Indigenizing Christianity

religious identities of Southeast Asia were largely formed by the experiences during the early modern period and continued to impact great influences in the later centuries.28

Barbara Watson Andaya tackles the challenges faced in the transplantation of Christianity in the early modern period in Southeast Asia and the unanticipated results and implications that arose (Chapter 13). Filomeno Aguilar intertwines the study of rice cultivation and its attendant spirituality with social relations (includ-ing gender relations), the intervention of Catholicism, and technological advances in the Philippines in the pre-colonial and Spanish colonial period (Chapter 14).

The avowed intention of the present volume is primarily to showcase some recent works on the four aforesaid themes. A balanced coverage of the Southeast Asian mainland and insular territories as well as region-wide treatment offer an overall treatment of this“early modern”period aimed at spurring further inquiry, exploration, and at the same time instigating debate, re-examination, reassess-ment, and/or simply re-looking at historical development. This is intended as a challenge to the increasing emergence of scholars from the region itself–born, schooled, and trained from within–to move forward the historical scholarship to another level leaving behind past baggage (Euro-centric, nationalist-oriented) to pioneer a breakthrough in achievement and excellence.

The aforesaid four themes and the chapters therein relating to the early modern era in Southeast Asia will further increase our current understanding of this historical phase as well as the period thereafter. Undoubtedly this present undertaking will challenge current viewpoints and perspectives and consequently spur extended discussions and debates. Only through open and continuous discourses could the boundaries of knowledge and understanding of the human journey be pushed forward, developed and expanded.

Notes

1 Leonard Y. Andaya and Barbara Watson Andaya, “Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Period: Twenty-Five Years On”,Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 26, 1 (1995): 92.

2 In 1968, the English translation by Sue Brown Cowing was published by East-West Center Press: Georges Coedès,The Indianized States of Southeast Asia, Honolulu, HI: Hawai'i University Press, 1968.

3 It is necessary to note that in Coedès' early writings, the region of Southeast Asia included some parts of “India beyond the Ganges”but excluded the Philippines, Assam, and northern Vietnam. See Coedès,The Indianized States of Southeast Asia, “Introduction”, p. xv.

4 According to G. Coedès, “the ancient history of Farther India” ended by “the arrival of the European”, that is the seizure of Malacca by the Portuguese in 1511. Ibid., p. xvii.

5 Anthony Reid, Charting the Shape of Early Modern Southeast Asia, Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2000, pp. 4–6.

6 D.G.E. Hall,A History of Southeast Asia, London: Macmillan, 1968, pp. 8–9. 7 Trần Quốc Vương,“Traditions, Acculturation, Renovation: The Evolutional Pattern

the 9th to the 14th Centuries, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, 1986, p. 277. 8 Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks,Early Modern Europe, 1450–1789, Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2006.

9 Peter Burke,“Can We Speak of an Early Modern World?”, IIAS Newsletter43, 2007, p. 10.

10 Harry J. Benda,“The Structure of Southeast Asian History”(Journal of Southeast

Asian History3, 1 (1962), pp. 106–138), cited inContinuity and Change in

South-east Asia. Collected Journal Articles of Harry J. Benda, New Haven, CT: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies, Monograph No. 18, 1972, p. 142.

11 Held in May 1984, the conference attracted some forty experts, including historians, archaeologists, anthropologists, linguistics and epigraphers. See: David G. Marr and A.C. Milner (eds),Southeast Asia in the 9th to 14th Centuries, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University and Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, 1986.

12 A detailed discussion can be seen in two enormous volumes by Anthony Reid,

Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce 1450–1680, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1988 and 1993.

13 Hall,A History of Southeast Asia, Part III (The Period of European Expansion), pp. 471–701.

14 David Joel Steinberg (ed.),In Search of Southeast Asia. A Modern History, Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai'i Press, 1987, p. 1.

15 An obvious example was the conference held at the Australian National Uni-versity in 1973, which later formed the monograph edited by Anthony Reid and Lance Castles, Pre-colonial State Systems in Southeast Asia: The Malay Penin-sula, Sumatra, Bali-Lombok, South Celebes, Kuala Lumpur: Monograph of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, No. 6, 1975.

16 Nicholas Tarling (ed.), The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, Vol. I: From Early Times toc.1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992 (Chapter 7). 17 Anthony Reid (ed.),Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era: Trade, Power, and

Belief, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993.

18 Leonard Y. Andaya and Barbara Watson Andaya,“Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Period: Twenty-Five Years On”, p. 93.

19 W.G. Cantwell-Smith, “Review of Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era”,

Southeast Asia Research2, 2 (1994): 201.

20 Barbara Watson Andaya and Leonard Y. Andaya, A History of Early Modern

Southeast Asia, 1400–1830, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. 21 Anthony Reid,Charting the Shape of Early Modern Southeast Asia, pp. 3, 7. 22 M.C. Ricklefset al.,A New History of Southeast Asia, London: Palgrave Macmillan,

2010, p. 134.

23 Nicholas Tarling (ed.),The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, Vol. I, pp. 402, 454. 24 See, for instance, Denys Lombard,“Another ‘Mediterranean’in Southeast Asia”,

Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies, 1 (2007): 3–9.

25 Anthony Reid, “An ‘Age of Commerce’ in Southeast Asian History”, Modern

Asian Studies, 24, 1 (1990): 1–30.

26 Victor Lieberman, Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–

1830, Volume Two: Mainland Mirrors: Europe, Japan, China, South Asia, and the Islands, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009 (Chapter 1).

27 Ibid., Vol. 2, p. 894.

28 See Barbara Watson Andaya,“Between Empires and Emporia: The Economics of Christianization in Early Modern Southeast Asia”, Empires and Emporia: The

Orient and World Historical Space and Time, edited by Jos Gommans,Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 52, 4–5 (2009): 963–97.

Part I

Diplomatic and

inter-state relations

“Diplomacy is to do and say the nastiest things in the nicest way.”

1

Status and security in early Southeast

Asian state systems

Nicholas Tarling

Introduction

Historians distrust other historians, as well as practitioners of other dis-ciplines, when they divide up time and label their periodization. Do the dates really mark “turning points” or are they arbitrarily imposed upon a con-tinuity? Can an era effectively be labelled as one of“violence”or an age one of “imperialism” without degrading a story that can meaningfully be told only in all its“detailed glory”?1As Herbert Butterfield argued, the answer, of course, is one of convenience. It is impossible to compose a book without a theme or analyse a situation without an assumption.

Is international order in modern times rightly described, as by students of IR (International Relations), in terms of“anarchy”? Is to be contrasted to a preceding order based on hierarchy? And if there was such a shift, can it be marked offby dates, even if they are striking or symbolic?

Recognising the convenience of such a contrast, particularly for a work of what Butterfield called “abridgement”, the historian will also wonder if the orders, hierarchy and anarchy, are quite rather different in practice as they seem to be in definition, quite so sharply distinguishable. For they have to do with common problems that continue over many centuries, even though the nature of the states that make up the order may change, their capacities advance, their wealth increase, their population grow.

Both orders have, for one thing, to deal with the fundamental issue of inter-state relationships, the disparity of power and its shifting distribution. The hierarchical system handles that by an explicit recognition of disparity that is also mutual: if the lesser know their place, they may be able to preserve or even enhance it. The characteristic relationship in such a system may be a lord–vassal or patron–client relationship, and/or the rendering and reception of tribute, always with the assumption that there is an element of obligation on the part of the superior as well as the inferior, that submission is counterparted by protection.

of their power, and the weaker their aspirations to equality. A range of supp-lementary options may help: the making of alliances, the pursuit of a balance of power, the creation of regional organizations. Tensions come with change, often leading to conflict, even wars, big or small.

Both systems are closely related to matters of allegiance or control. In the ancient system the state did not have the power that the modern state has and seeks. It might be content with a diminished allegiance at least outside its core and with indefinite frontiers. It might control its people loosely, exercising symbolic rather than actual control, its officers exemplifying rather than enforcing appropriate behaviour. It might allow“foreigners”more or less to rule themselves, rather than attempting to assimilate them, or even use them as an instrument of control over others. The modern state looks for more: it seeks definite frontiers, within which citizens or subjects owe it services and taxes, and“minorities” have such rights as an entity ruled by or based on a “majority” sees fit to allow them.

In both systems what we may call “diplomacy” is at work. In our system we are aware of the functions of ambassadors, the use of “summits”, the manipulation of the media, the pursuit of intelligence: we know of the pro-cesses, even though we may know little of their content. There has been something of a tendency not to think of the ancient systems in a similar way, but rather to assume that they were a kind of semi-celestial clockwork. Yet surely they also were operated by men with schemes and ambitions, and their systems, symbolic though they might be, were also subject to manipulation. They not only worked: they might be worked. The Balinese king was not simply an icon, as H. Schulte Nordholt points out, but“a charismatic leader of flesh and blood who had to overcome constant threats to his position”.2 The idea that spectacle was not for the state but what the state was for would have seemed odd to Elizabeth I and Louis XIV, but odd, too, to the courtiers of Sultan Agung of Mataram, who, as Merle Ricklefs says,“thought that the state was for getting rich and powerful while avoiding enemy plots and treasons”.3

Dealing with similar problems, the systems were in some ways similar, less distinctive than a schematic approach suggests, less cut-and-dried. Nor can the chronological divisions be so sharp as dates or labelling imply. Hierarchy did not prevail throughout the period of hierarchy, nor did it entirely dis-appear in the period of anarchy. Nor, on the other hand, did “anarchy” emerge full-blown as Minerva from the mind of Jupiter. In Europe itself, it came to prevail only over two centuries and more, and what is often called the Westphalia system was not simply established with the treaty of 1648 that labels it.

peculiar, if not indeed paradoxical structure, the colonial state. Only with the decolonization that followed the end of the Second World War (1939–45) could it be said that “anarchy” extended across the world and the colonial phase itself be seen as one of transition, with Europeans operating two dif-ferent systems. The states that emerged were so disparate in power, however, that their mutual accommodation at times prompted observers and prophets to recall the days, if not of empire, then indeed of hierarchy. But perhaps the “ASEAN way”is something different again.

Tackling these issues with a regional approach, and including Southeast Asia as a region, are welcome strategies, and, it may be shown, profitable ones. In the past, neither public nor scholarly debate was ready to identify it as a region, and even in recent works of generalization or popularization it tends to be by-passed. When it was distinguished in the past, it was often labelled in a misleading way: it was“Further India”, the Nanyang, the Nan-yo. Public events–the Second World War in particular–led to the wider adoption of a more neutral geographical labelling, and it was filled out by both poli-tical and academic activities. Histories of “Southeast Asia” appeared in the 1950s – magisterially led by D.G.E. Hall’s – and the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) – its leaders, conscious of the past as well as the present– was inaugurated in 1967. It was a diverse region, but that was not a reason for not seeing it as a region either for action or for study. Rather the reverse.

Students of the region, as well as statesmen, both sought commonalities, however, and it may be that it still retains, albeit in modified form, practices inherited from a past that temporally is after all not so distant, even if in the interim the region has been the scene of unprecedented change. One feature of the last 150–200 years is its shift from demographic immaturity: perhaps there were only 30 million people in Southeast Asia in 1830. Certainly in the more remote past what counted among the state-builders of Southeast Asia had been men rather than land, and the attitudes that established arguably help to account for the contemporary strength of patron–client relationships.

Whether the Southeast Asian past is peculiar in this may be doubted. What may be special about the Southeast Asian region – though still helpful in comparative studies– is its cultural diversity. It was penetrated by a range of peoples, but also subject to the influence of two great neighbours, India and China. What the process of that influence was has been disputed among his-torians. The generally accepted conclusion is that state-builders in the region borrowed from these cultures, in particular from India. At times, if not more generally, China, however, asserted its primal claim: exceptionally, in the Vietnamese case, in the form of political dominance, more usually in the form of a pattern of tributary relationships.

It is the product of this mix, neither hierarchy nor anarchy, with which Europeans came into contact from the early sixteenth century. To understand their approach and their impact requires a fuller analysis of it and of the states of which it was made up.

Herman Kulke suggests that there were three phases or levels in state for-mation in Southeast Asia: the local, the regional, and the“imperial”. “Very generally speaking, thefirst step always had to be the successful establishment and consolidation of a solid local power within a limited territory.” This he characterizes as“chieftaincy”. Next might come the conquest of one or more neighbouring nuclear areas, incorporated not by annihilation nor by admin-istrative unification, but by the establishment of more or less regular tributary patterns. These were the somewhat precarious “early kingdoms”. From the early ninth century a small number of what Kulke calls“imperial”kingdoms emerged, beginning with Angkor, which unified two or even several core areas of former early kingdoms.4

That word“mandala”was deployed by Stanley Tambiah and in particular by Oliver Wolters, drawing from the Indian political literature and practice that influenced Southeast Asia. The former analysed Kautilya’sArthashastra, the only complete work of the brahmanic politico-economic literature to be preserved, made notorious for its alleged Machiavellianism by Max Weber.5

It deals inter alia with the maintenance of“state sovereignty”and the conduct of diplomacy, making alliances, making war, according to themandalastrategy, in which successive“circles of kings”formed enemies and allies in actuality or in potentia.

Tambiah also analysed the Buddhist texts. In them dharma, righteousness, is an absolute imperative. Its symbol in political life was the wheel, cakka, not the sceptre, danda. In his past lives the Buddha admitted that, as a wheel-turning raja, he used violence.“The Cakkavarti [sic] is depicted as a cosmo-crator whose conquest proceeded through the continents at each of the four cardinal points, and whose rule radiated out from a central position either identified or closely associated with the central cosmic mountain of the Indian traditions, Mount Meru.” The cakkavatti grants their domains back to the conquered kings when they submit to the basic moral precepts of Buddhism: “in a sense the king must let the conquered rulers keep their thrones, since only as a king of kings is he a world monarch.” The Emperor Asoka embraced the model, and he was in turn the model for many Southeast Asian Buddhist monarchs.6

Before he turns to them Tambiah describes the empire of their exemplar. Asoka’s Mauryan state “was not so much a bureaucratized centralized imperial monarchy as a kind of galaxy-type structure with lesser political replicas revolving around the central entity and in perpetual motion offission or incorporation. Indeed, it is clear that this is what the much-citedcakkavatti model represented: that a king as a wheel-rolling world ruler by definition required lesser kings under him who in turn encompassed still lesser rulers, that the raja of rajas was more a presiding apical ordinator than a totali-tarian authority between whom and the people nothing intervened except his own agencies and agents of control.” The model was “a closer repre-sentation of actual facts than has usually been imagined by virtue of misreading the rhetoric”.7

It was the concept of mandala, Tambiah tells us that led him to invent the label“galactic polities”. In a common Indo-Tibetan tradition, mandala was composed of a core, manda, and an enclosing element, -la, and it was applied to designs, diagrams and cosmological schemes. Representing a cosmic harmony, it was a pattern for the state.“In the center was the king’s capital and the region of its direct control, which was surrounded by a circle of provinces ruled by princes or governors appointed by the king, and these again were surrounded by more or less independent‘tributary’polities.”The capital itself was a mandala, with the palace at the centre, surrounded by three circles of earthen ramparts, four gateways at the cardinal points. Each lesser unit replicates the larger, and is more or less autonomous,“held in orbit and within the sphere of influence of the center”. At the margin, however, are“similar competing central prin-cipalities and their satellites”. The system is “a hierarchy of central points continually subject to the dynamics of pulsation and changing spheres of influence”. Territorial jurisdiction was not characterized by fixed boundaries but byfluidity. Behind its cosmology and the“ritually inflated notions we see the dynamics of polities that were modulated by pulsating alliances, shifting territorial control, and frequent rebellions and succession disputes”.8

The modern literature on these polities has tended not to adopt Tambiah’s celestial metaphor. Instead, it might be said, Oliver Wolters effectively pre-sented them in terms of the mandala that had set him offin thefirst place, a word Kautilya had indeed used as a geopolitical concept, configuring friendly and enemy states.

The map of earlier Southeast Asia which evolved from the prehistoric networks of small settlements and reveals itself in historical records was a patchwork of often overlapping mandalas, or circles of kings. In each of these mandalas, one king, identified with divine and“universal” author-ity, claimed personal hegemony over the other rulers in hismandalawho in theory were his obedient allies and vassals.9

Wolters borrowed another metaphor from music.“Mandalas would expand and contract in concertina-like fashion. Each one contained several tributary rulers, some of whom would repudiate their vassal status when the opportunity arose and try to build up their own networks of vassals.”

Wolters draws attention to two of the political skills required. One was the gathering of “political intelligence”, finding out what was happening on the fringe of the mandala, so that threats might be anticipated. The other was diplomacy. An overlord had to be able to bring his rivals under his personal influence“and accommodate them within a network of loyalties to himself.… Administrative power as distinct from sacral authority depended on the man-agement of personal relationships, exercised through the royal prerogative of investiture”, the same skill as attributed to earlier“men of prowess”. He had to attract loyal subordinates and preserve their loyalty.“[A]dministrative power as distinct from divine authority had…to be shared.”10

Whatever metaphor is adopted, historical example helps. In the Angkor court, as Ian Mabbett tells, there was a“web of obligation and influence. … Power was … something that arose from relationships and needed to be negotiated”.11 “Bureaucratic apparatuses were mostly Indianized fiction”, writes Renée Hagesteijn: “a ruler was dependent on patron–client relations with ‘lesser’ political leaders.”12 At the centre the supraregional leader had direct relations with the headman. Regional leaders were clients, offered pro-tection, honours and gifts. On the periphery control was“almost lacking”.13

What was true of the mainland was true also of the archipelago, true of the thalassocracy that Georges Coedes uncovered in Srivijaya and Wolters so persistently expounded, true also of the land-based states of Java. There, the capital was“the magical centre of the realm”, as Soemarsaid Moertono put it,“but also, from the point of view of state politics, the central region was preponderantly important. … [T]he core region was relatively closely knit through the use of a remuneration system of appanages, while the outer regions were more loosely administered.” In the empire of Majapahit, as described in theNâgarakertagâma, there were three regions: Java at the centre, the islands outside it and countries beyond, like Champa and Cambodia. Later Mataram was composed of the core, nagaragung, the outer provinces, man-tjanegara andpasisir, and the lands across the sea, tanah sabring. Territorial jurisdiction was“characterized by afluidity orflexibility of boundary dependent on the diminishing or increasing power of the center”.14

It was a form of inter-entity politics that welcomed, utilized and adapted the tradition and practice India had developed. India itself, however, was an exemplar, not an active part of the system. No Indian empire laid a larger claim over the Indianized states of Southeast Asia: the sub-continent was perhaps more than challenge enough. But, given their geographical position, it was not surprising to find that Southeast Asian states, largely Indianized though they were, might see their neighbour to the north, the Chinese empire, which had met the challenge of political unification, as the apex of a hierarchy that included them. It was a question of force, but also of accommodation and mutual advantage.

China developed a view of the“world”as it“knew”it. Outside countries, if in contact, were tributaries, and trade conducted in that context.15 What or