Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 19 January 2016, At: 19:58

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Bureaucrats as entrepreneurs: a case study of

organic rice production in East Java

Suradi Martawijaya & Roger D. Montgomery

To cite this article: Suradi Martawijaya & Roger D. Montgomery (2004) Bureaucrats as entrepreneurs: a case study of organic rice production in East Java, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 40:2, 243-252, DOI: 10.1080/0007491042000205303

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0007491042000205303

Published online: 19 Oct 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 76

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, Vol. 40, No. 2, 2004: 243–52

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/04/020243-10 © 2004 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/0007491042000205303

Carfax Publishing

Taylor & Francis Group

BUREAUCRATS AS ENTREPRENEURS:

A CASE STUDY OF ORGANIC RICE

PRODUCTION IN EAST JAVA

Suradi Martawijaya

Brawijaya University, Malang

Roger D. Montgomery*

Independent Consultant, London

The sustainability of inorganic ‘green revolution’ rice-growing technology has been called into question because of the resulting depletion of soil quality and the sus-ceptibility of crops to pest infestations. This, together with health concerns about the use of chemicals in the production of foods, raises the question of whether it might be feasible to return to organic methods for the production of rice in Indonesia. This paper describes an experiment along these lines. It was found that organic farming methods could be used with only a small decline in yields per hectare, but that local demand for organic rice produced domestically was not strong enough to generate sales at prices that would cover higher production costs. If organic farming methods are to be adopted in Indonesia, therefore, it may be nec-essary to focus on exporting to countries where there is a potentially strong con-sumer demand for organic rice.

INTRODUCTION

The ‘green revolution’ was seen as an important step in helping feed the world’s hungry, allowing food production to be increased significantly from 1964 onward. Simply put, the green revolution for rice and wheat meant cultivation using high-yield seeds, together with chemical fertilisers, pesticides and herbi-cides. The success of the green revolution spilled over to Indonesia, which became self-sufficient in rice in 1984, having for decades been the largest rice importer in the world. Since 1984, Indonesia has remained a minor net rice importer (except in El Niño years, when imports were substantial).

But the green revolution in Indonesia over the last two decades has had a darker side. First, it is accused of damaging soils and depleting them of organic matter.1Research by East Java’s Food Crop and Horticulture Protection Institute (Balai Proteksi Tanaman Pangan dan Holtikultura Jatim) shows that rice paddy soils regularly treated with chemical fertilisers now contain only 1.7% organic matter. By contrast, a study by Supardi (1983) determined that the organic matter content of rice paddy soil should be about 5%, based on water and nutrient reten-tion capability and on the stability of the soil to support plant roots. Moreover, farmers complain of having to use an increasing amount of urea to fertilise the

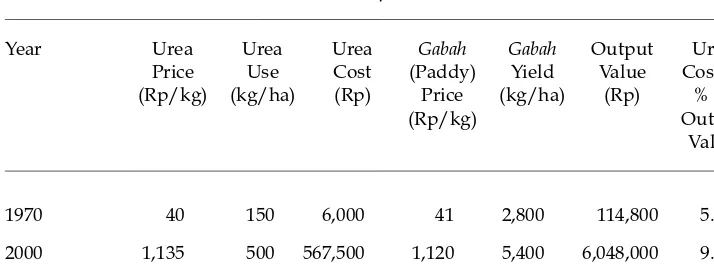

soil every season. In 1970, farmers in Lumajang, East Java, for example, needed only 150 kg of urea per hectare, compared to the 500 kg now required to achieve an equivalent output (Poniman 2002). Fertiliser costs as a proportion of the value of output have thus risen significantly (table 1).

The second problem was susceptibility to insects. Between 1974 and 1979, the new green revolution rice varieties in Java and Bali experienced a widespread infestation of brown plant hopper (Nilaparvata lugens, or wereng), which destroyed an average of 420,000 hectares of rice fields each year (1970–99 data provided by the Central Statistics Agency, BPS). Conventional spraying with widely available broad-spectrum insecticides was ineffective; the insecticides killed not only the werengbut also its natural predators. This merely increased the

werengproblem when the insect re-established itself.2

As a result of these concerns some analysts are now questioning the long-run sustainability of inorganic rice production methods,3and looking at the possibil-ities for a return to organic farming methods. At the same time there is a growing urban consumer movement toward pure, natural food, free from the residues of chemical fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides, and from artificial hormones. Organic food sections are now found in all major supermarkets, not only in Jakarta but in most provincial cities. In the last decade, the consumption of organic foods increased by 22.5% annually on average (Sulaiman 2001), and demand is predicted to rise further.

The key problem with marketing organic rice is that consumers have no way of distinguishing it from the same kind of commodity produced using inorganic methods. If unit prices were the same for both this would not be a problem, since there would be no reason to mislabel the product. But organic rice is more expen-sive to produce—after all, the development of inorganic methods was the direct consequence of the attempt to reduce production costs—and must therefore sell at a higher price if it is to be commercially viable. There is therefore an incentive for producers, wholesalers and retailers to misrepresent inorganic rice as organic, in order to be able to sell it at the higher price that consumers concerned about chemical residues and damage to the environment are prepared to pay. In an attempt to prevent such behaviour, various organisations have emerged that

pro-TABLE 1 Cost and Yield Comparison between 1970 and 2000

Year Urea Urea Urea Gabah Gabah Output Urea Price Use Cost (Paddy) Yield Value Cost as (Rp/kg) (kg/ha) (Rp) Price (kg/ha) (Rp) % of

(Rp/kg) Output

Value

1970 40 150 6,000 41 2,800 114,800 5.2

2000 1,135 500 567,500 1,120 5,400 6,048,000 9.4

Source: BPS (2001).

vide certification services on which buyers of organic produce can rely. But con-sumers remain sceptical about the validity of certification.

LOCAL GOVERNMENT INVOLVEMENT IN ORGANIC RICE CULTIVATION

With the onset of regional autonomy in 2001, the district (kabupaten) of Lumajang in East Java began to plan the implementation of organic rice agriculture. It was the first kabupatenin the province to do so. Lumajang’s organic agriculture is cer-tified by the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM).4Such certification is intended to protect consumers from fake organic

products, and to protect farmers from fake input products. In general, it assures all interested parties that the entire sequence of production, preparation, storage, transportation and marketing phases complies with internationally applied organic system requirements. From 2001, organic rice agriculture in the Lu-majang subdistricts (kecamatan) of Pronojiwo and Candipuro became the subject of government regulations:

1 Governor of East Java, Letter No. 520/2732/022/2001, dated 4 April 2001, gave instructions on organic rice development in kabupatenLumajang;

2 The Budget of the Project on Food Security Improvement in kabupaten Lu-majang (2002), article 2P.02.1.01.001, subsidised farmers for the first organic planting; and

3 Decision No. 18845/161/434.12/2002 of the bupati(district head) of Lumajang, dated 20 February 2002, gave operational instructions for organic farming.

IMPLEMENTATION OF ORGANIC RICE FARMING IN LUMAJANG

To overcome the problem of small farm size, the Lumajang administration tried requiring groups of farmers to cultivate their land at the same time, on a proto-collective farm model. This presumes some element of economies of scale. Although the land parcels are still owned or occupied by individual farmers, cul-tivation and marketing are done jointly. This communal land concept is imposed; it does not arise from farmers’ wishes or their own perceived self-interest. They are guided and assisted to organise, working in groups in order to increase pro-ductivity.

The target area determined for organic rice agriculture development in 2002 was 100 hectares, located in kecamatan Pronojiwo (75 hectares) and kecamatan

Candipuro (25 hectares). The adopted model followed an example from Thailand.5On the basis of the governor’s letter, kabupatenLumajang undertook a

location survey for organic rice agriculture in the kecamatan of Sukodono, Tempur Sari, Pronojiwo and Candipuro. Although there were many locations suitable for organic rice agriculture in kabupaten Lumajang, only a few farmer groups were willing to participate:

• the Among Tani farmers group (57 members) and the Tani Mulya farmers group (15 members) in kecamatan Pronojiwo (referred to below as the Pronojiwo farmers group); and

Bureaucrats as Entrepreneurs: Organic Rice Production in East Java 245

• the Kalijambe farmers group (15 members) in kecamatanCandipuro (referred to below as the Kalijambe farmers group).

After the locations and farmer groups were chosen, the regional administra-tion, together with the kabupaten agricultural agency office, carried out various activities to ‘socialise’ the project plan. Training courses were used to add to farm-ers’ skills; these were attended by 45 farmers, 15 from each of the three groups. Discussions were also held with the prospective rice buyers: two rice trading cooperatives and one private company (Nusantara Cooperative, Srigati Co-operative and CV Agro Alam Lestari). These organisations agreed to market the rice as an organic product, expecting that it could be sold at a significantly higher price than inorganic rice. They did not, however, undertake a market survey to establish whether this was a realistic expectation. Srigati and Agro Alam Lestari later went back on their commitments to purchase the organic rice, having realised there were likely to be significant marketing problems.

The government, farmer groups and buyers agreed on a price of Rp 1,700/kg for organic paddy rice (gabah kering panen, dry threshed paddy). This represents a premium of about 30% over the price of Rp 1,300/kg for ordinary paddy rice. Selling prices were expected to increase because of the assumed existence of strong local consumer demand for organic rice, and it was implicitly expected that the price premium would more than offset the higher cost of the organic fer-tilisers needed.6

ORGANIC RICE CULTIVATION TECHNIQUES USED IN LUMAJANG

The annual production patterns of organic and inorganic farms are much the same. The dominant factor that influences the pattern is not whether organic technology is employed but location, especially altitude. Pronojiwo and Candipuro have two crops per year, either rice and rice for the first and second season or rice for the first and chilli for the second. The production patterns and techniques used by each farmer group are shown in the appendix.

The types of organic fertilisers used included bokasi and kascing. Bokasi is a decomposed mash consisting of a mixture of straw, rice husks, rice polishings, sugar, water and a decomposing agent, Effective Micro-organism Four (EM-4).7

Kascing(an acronym of bekas cacing, or worm-manure) is a new organic fertiliser (Musnamar 2003: 39). One or more species of earthworms is grown in a medium that can consist of decomposed wet rice straw, rice husks, sawdust, leaves, banana stalks, maize husks and other fibrous plants. Once the earthworms are introduced into this decomposed medium they are fed with various leaves, espe-cially those of leguminous plants. The worms can also be fed livestock dung. After 60 days of growth in the combined medium, worms, worm-manure and feed remnants are harvested, subjected to further processing and then sold to farmers in the shape of pellets. Prepared growing medium and worm-feed are now appearing in the markets for sale to farmers who want to speed up the process of growing worms.

In addition to organic fertilisers, the organic pest control techniques included the introduction of Trichogramma(tiny wasps), used as a parasitoid to kill the eggs and larvae of insects.8 The farmers in Lumajang also used Beauveria bassiana, a

fungus that grows on insects and controls them by secreting enzymes that weaken the insect and cause a condition known as ‘white muscadine disease’.9

COST COMPARISON OF ORGANIC AND INORGANIC RICE

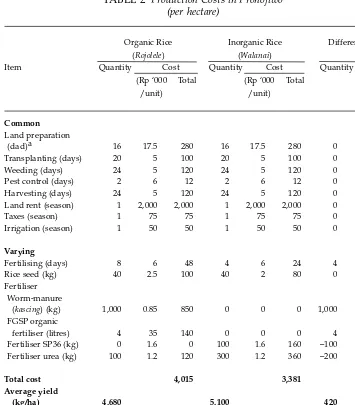

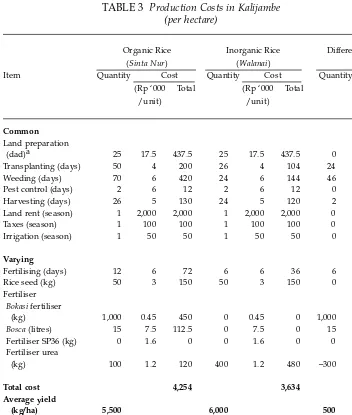

Tables 2 and 3 compare production costs for organic and inorganic rice in the sec-ond period of cultivation by the Pronojiwo and Kalijambe farmer groups. The unit cost of producing paddy rice in Pronojiwo was higher by Rp 195 per kilo-gram for organic than for inorganic rice (table 2). The inorganic rice yield was about 420 kg per hectare, or 9%, higher. In Kalijambe, the cost of producing paddy rice was higher by Rp 168 per kilogram for organic than for inorganic rice; the yield differential was also 9% (500 kg per hectare) (table 3).

MARKETING: THE FORGOTTEN ELEMENT

Tables 2 and 3 show, not surprisingly, that production costs are higher for organic than for inorganic rice farming. Thus farmers would need to sell the organic rice at a significant premium over the inorganic rice price to obtain profits similar to those they have been used to. The designers of Lumajang’s organic rice experi-ment had not considered whether there would be enough consumer demand for organic rice at a sufficient premium for it to be commercially viable. It is not sur-prising, therefore, that the experiment proved to be a financial fiasco. When the Srigati Cooperative and CV Agro Alam Lestari broke their commitment to buy the organic rice, it sat unsold in the Nusantara Cooperative’s warehouse for some time, until the cooperative finally unloaded it on the market at a mere Rp 50/kg premium over inorganic rice. The Lumajang administration strongly urged civil servants to buy some of the rice in order to bail out the cooperative.

In taking this investment risk with the public’s money, the officials of the Lumajang administration completely failed to investigate how far consumers perceived a difference (and one worth paying for) between organic and non-organic rice, and whether those who did could be persuaded that the rice was in fact produced using organic technology. Organic food consumers evidently doubted the veracity of organic labelling, which is hardly surprising in a country with a highly corrupt legal system. Any producer can print the word ‘organic’ on a label, as there is almost no chance of legal proceedings if the claim is fraudulent. For the majority of sceptical consumers, solid evidence is required: certification or accreditation by a reputable organisation.

The Indonesian National Committee for Accreditation (KAN, Komite Akredi-tasi Nasional) has neither the independence nor adequate resources and tools to carry out this job. KAN is an entirely government-sponsored operation, set up under the National Standards Board (Badan Standardisasi Nasional).10 Ideally

the certification body should be independent, free and unattached to any food production and marketing business. KAN does not meet these criteria.11IFOAM

does meet them, but is a small organisation located in Germany, and has neither policing nor enforcement capability. The Ministry of Agriculture is the competent authority in this regard, but to date it has not accepted the challenge presented. Even if it were to do so, there can be no presumption that Indonesian consumers would trust the government to oversee the work of an accreditation body.

Bureaucrats as Entrepreneurs: Organic Rice Production in East Java 247

CONCLUSION

The experiment described here has produced results that are the typical conse-quence of government officials acting as entrepreneurs in the absence of the stern discipline that exists when the entrepreneur’s own funds are at risk. One of the most basic rules of business is that there is no point in producing something if it cannot be sold at a price that will more than cover costs of production. Thorough market research is therefore essential before any further attempt is made to pop-ularise a return to organic methods of rice production in Indonesia. It is vital to know what the final consumers (and supermarkets) require in terms of certifica-tion and labelling, and which agencies are trusted in this respect.

TABLE 2 Production Costs in Pronojiwo (per hectare)

Organic Rice Inorganic Rice Differences (Rojolele) (Walanai)

Item Quantity Cost Quantity Cost Quantity Cost

(Rp ‘000 Total (Rp ‘000 Total (Rp

/unit) /unit) ‘000)

Common Land preparation

(dad)a 16 17.5 280 16 17.5 280 0 0

Transplanting (days) 20 5 100 20 5 100 0 0

Weeding (days) 24 5 120 24 5 120 0 0

Pest control (days) 2 6 12 2 6 12 0 0

Harvesting (days) 24 5 120 24 5 120 0 0

Land rent (season) 1 2,000 2,000 1 2,000 2,000 0 0

Taxes (season) 1 75 75 1 75 75 0 0

Irrigation (season) 1 50 50 1 50 50 0 0

Varying

Fertilising (days) 8 6 48 4 6 24 4 24

Rice seed (kg) 40 2.5 100 40 2 80 0 20

Fertiliser Worm-manure

(kascing) (kg) 1,000 0.85 850 0 0 0 1,000 850 FGSP organic

fertiliser (litres) 4 35 140 0 0 0 4 140

Fertiliser SP36 (kg) 0 1.6 0 100 1.6 160 –100 –160

Fertiliser urea (kg) 100 1.2 120 300 1.2 360 –200 –240

Total cost 4,015 3,381 634

Average yield

(kg/ha) 4,680 5,100 420

Unit cost (Rp/kg) 858 663 195

adad = draft animal days.

To put it differently, organic agriculture development elsewhere in world tends to be ‘bottom up’, while in Lumajang it has been ‘top down’. The experiment has suffered all the usual faults of top-down planning, resulting in losses to the coop-erative that was persuaded to purchase organic rice from farmers in the absence of effective consumer demand for it, followed by requests for subsidies and bailouts. Organic farming can only become widespread if there is a strong demand for organic products, and this will require the existence of one or more accreditation organisations regarded as trustworthy by consumers.

Indonesia might do well to learn from East Timor’s success with organically grown coffee, which is exported with considerable success to the US and other

Bureaucrats as Entrepreneurs: Organic Rice Production in East Java 249

TABLE 3 Production Costs in Kalijambe (per hectare)

Organic Rice Inorganic Rice Differences (Sinta Nur) (Walanai)

Item Quantity Cost Quantity Cost Quantity Cost

(Rp ‘000 Total (Rp ‘000 Total (Rp

/unit) /unit) ‘000)

Common Land preparation

(dad)a 25 17.5 437.5 25 17.5 437.5 0 0

Transplanting (days) 50 4 200 26 4 104 24 96

Weeding (days) 70 6 420 24 6 144 46 276

Pest control (days) 2 6 12 2 6 12 0 0

Harvesting (days) 26 5 130 24 5 120 2 10

Land rent (season) 1 2,000 2,000 1 2,000 2,000 0 0

Taxes (season) 1 100 100 1 100 100 0 0

Irrigation (season) 1 50 50 1 50 50 0 0

Varying

Fertilising (days) 12 6 72 6 6 36 6 36

Rice seed (kg) 50 3 150 50 3 150 0 0

Fertiliser Bokasifertiliser

(kg) 1,000 0.45 450 0 0.45 0 1,000 450

Bosca(litres) 15 7.5 112.5 0 7.5 0 15 112.5

Fertiliser SP36 (kg) 0 1.6 0 0 1.6 0 0 0

Fertiliser urea

(kg) 100 1.2 120 400 1.2 480 –300 –360

Total cost 4,254 3,634 620.5

Average yield

(kg/ha) 5,500 6,000 500

Unit cost (Rp/kg) 773 606 168

aSee table 2, note a.

countries. It seems quite possible that export markets—specifically, in developed countries where concerns about the environment and about chemical residues in food are much greater—may be a more promising avenue through which to expand organic rice production, relying on credible accreditation from bodies such as IFOAM.12

NOTES

* Thanks are due to two anonymous reviewers for their careful reading, their very help-ful comments and their suggestions for simplification and clarification. The authors are also grateful for the valuable help and information provided by Pak Utomo of the Lumajang Department of Agriculture, Pak Heri Gunawan, head of the farmers groups in Lumajang, and Pak Paiman, head of the Lumajang Local Planning and Development Agency.

1 Recent research by the Assessment Institute for Agricultural Technology (Balai Pengkajian Teknologi Pertanian) in Malang shows that 80% of Java’s agricultural land suffers from low organic content. This is said to be due to the application of inorganic inputs (chemical fertiliser and pesticide) introduced through the former nationwide Bimas (Bimbingan Massal) rice intensification and food self-sufficiency program (Dudung Abdul Adjid et al.1998).

2 For further information on the dangers of chemical pesticides, see www.toxictrail.org and www.tve.org, websites sponsored by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

3 Reijntjes et al.(1999) discuss the issue in the context of Punjab, India, for example. 4 See www.ifoam.org/standard/index.html for more information on how IFOAM

oper-ates. Located in Hofgut Imsbach, Germany, IFOAM works with UNCTAD and the FAO. Normally its responsibility is to give accreditation to national bodies that in turn certify organic production and processing. The organisation has neither direct inspec-tion nor enforcement capability (other than to withdraw accreditainspec-tion).

5 Thailand’s organic agriculture developed as a result of full support from the king and the goverment, which provided financial incentives during the early years of organic agriculture development (Agung 2002). The government also provided important information on production techniques and markets for fertiliser and seed. In contrast with the Thai model, the Lumajang district government provided information on pro-duction techniques but not on markets.

6 Supporters of organic rice farming methods also argue that in the long term these methods will result in soils becoming more fertile, so that smaller quantities of fertiliser will be needed. The experiment described here does not address this empirical ques-tion, however.

7 See Musnamar (2003) for an Indonesian language discussion of the use of EM-4. 8 Knutson (2003) presents a handy manual and guide to the use of these wasps. 9 The reader is directed to various websites for technical information on this method of

pest control: see, for example, US EPA (1999) and University of Connecticut (nd), and the French national research system’s website, www.inra.fr/internet/products. 10 For information on how KAN operates see www.bsn.go.id/41P.htm and www.

agrimutu.com/ak/lab_sert_produk.htm.

11 KAN was set up by Presidential Decision No. 78 in 2001. See the environment min-istry’s website, www.menlh.go.id/i/art/pdf_1038467005.pdf, for the legal basis. 12 For a discussion of the size of markets for organic food products in a number of

advanced economy markets see Winarno (2003).

REFERENCES

Agung, Purwoto (2002), ‘Produk Pangan Organik, Potensi yang Belum Tergarap Optimal [Organic Food Crops, A Potential Not Yet Managed Optimally]’, Kompas, 19 July. BPS (Badan Pusat Statistik) (2001), Statistik Harga Produsen Sektor Pertanian di Indonesia

[Producer Price Statistics for the Agriculture Sector in Indonesia], Jakarta.

Dudung Abdul Adjid, Sudarno Sumarto, Syaikhu Usman, Sulton Mawardi and Roger Montgomery (1998), Government and Private Sector Roles in Facilitating Small Farmer and Agribusiness Development, Study B-1 of the 9-volume Asian Development Bank

Agricultural Sector Strategy Review, ADB TA 2660-INO, Asian Development Bank, Ministry of Agriculture, Jakarta.

Knutson, Allen (2003), The Trichogramma Manual, Publication B-6071, Texas A&M University System Agricultural Extension Service, College Station TX, available at: insects.tamu.edu/extension/bulletins/b-6071.html.

Musnamar, Effi Ismawati (2003), Pupuk Organik: Cair dan Padat, Pembuatan dan Aplikasi

[Organic Fertiliser: Liquid and Solid, How to Make and How to Apply It], Penebar Swadaya, Jakarta, www.trubus-online.com/penebar.

Poniman (2002), ‘Pertanian Organik: Upaya Menafikan Pupuk Kimia [Organic Agri-culture: Efforts to Eliminate Chemical Fertilisers]’, Kompas, 30 May.

Reijntjes C., B. Haverkort and A. Waters-Bayers (1999), Pertanian Masa Depan: Pengantar Untuk Pertanian Berkelanjutan dengan Input Luar Rendah, translation by Y. Sukoco of

Farming for the Future: An Introduction to Low-External Input and Sustainable Agriculture

(1992), Penerbit Kanisius, Yogyakarta.

Sulaiman, Imam (2001), Potensi dan Strategi Pengembangan Beras Organik di Jawa Timur

[Potential and Strategies for the Development of Organic Rice in East Java], Yayasan Inovasi Tani Indonesia, Surabaya.

Supardi, Guswono (1983), Sifat dan Ciri-ciri Tanah [The Nature and Characteristics of Land], Institut Pertanian Bogor [Bogor Agricultural Institute], Bogor.

University of Connecticut, Integrated Pest Management (nd), Using Beauveria bassiana for Insect Management, available at: www.hort.uconn.edu/IPM/index.html.

US EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) (1999), ‘Beauveria bassiana Factsheet’, www.epa.gov/pesticides/biopesticides/ingredients/factsheets/factsheet_128818.htm. Winarno, F.G. (2003), ‘Pangan Organik di Asia Pasifik [Organic Food in the Asia Pacific

Region]’, Kompas, June.

Bureaucrats as Entrepreneurs: Organic Rice Production in East Java 251

APPENDIX

In Pronojiwo, the farmer groups Among Tani and Tani Mulya used the following pattern and techniques, planting in the main growing season:

Time

Seeding in seed bed 1 to 30 January 2002

Transplanting 26 January to 19 February 2002

Harvesting June 2002

Dose of inputs per hectare

Seed (Rojolele, Walanaivarieties) 40–50 kg Organic fertiliser (kascing, worm-manure) 1 tonne

Liquid organic fertiliser FGSP 4–5 litres

Urea fertiliser as starter 100 kg

Organic parasitoid Trichogrammaspp. 50 pias(a 2 x 5 cm container, with more than 1,000 wasp eggs)

Organic agent Beauveriaspecies 1 litre

Organic plant pesticide 1 litre

In Candipuro, the farmer group Kalijambe used the following pattern and tech-niques, planting in the dry season (with irrigation):

Time

Seeding in seed bed 17 July to 30 July 2002

Transplanting 23 July to 25 August 2002

Harvesting December 2002

Dose of inputs per hectare

Seed (Sinta Nurvariety) 50 kg

Bokasifertiliser (solid) 1 ton

Bokasifertiliser (fluid) 15 litres

Urea fertiliser as starter 100 kg

Parasitoid Trichogrammaspecies 50 pias

Organic agent Beauveriaspecies 1 litre

Organic plant pesticide 1 litre