Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Interdisciplinary Dimensions in Entrepreneurship

Nancy M. Levenburg , Paul M. Lane & Thomas V. Schwarz

To cite this article: Nancy M. Levenburg , Paul M. Lane & Thomas V. Schwarz (2006) Interdisciplinary Dimensions in Entrepreneurship, Journal of Education for Business, 81:5, 275-281, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.5.275-281

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.5.275-281

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 126

View related articles

ABSTRACT.Entrepreneurship

pro-grams and courses are offered by many

business schools to support students who

aspire to start, own, and operate businesses.

Although these offerings are directed

pri-marily toward business majors, based on

data the authors collected from over 700

students, many nonbusiness majors also

possess entrepreneurial characteristics and

perceive the need for entrepreneurship

cur-ricula. The findings suggest that although

business majors regard their traditional

edu-cation as adequate preparation to start a

new business, the greatest need for

entre-preneurship courses and curricula exists

within academic disciplines outside of the

business school.

Copyright © 2006 Heldref Publications

management, accounting, and finance) may inadequately serve entrepreneurial students. Traditional specialized majors within business schools are frequently designed from the perspective that grad-uating students will seek employment in specialized departments within large established firms. However, students who are interested in creating new busi-nesses (i.e., entrepreneurship) need to develop an array of skills that will sup-port their new ventures (e.g., planning, risk taking, market analysis, problem solving, and creativity; McMullan & Long, 1987). This is because success-fully launching a new venture requires the mastery and blending of skills that are different from those required to maintain—or even grow—an estab-lished business.

While new venture opportunities exist within nearly all academic disciplines (e.g., graphic arts, nursing, computer sci-ence), the majority of entrepreneurship initiatives at U.S. colleges and universi-ties are offered by business schools (Ede, Panigrahi, & Calcich, 1998; Hisrich, 1988) and for business students (e.g., Roebuck & Brawley, 1996). In fact, most studies that have been conducted to explore entrepreneurial intent among college students have focused on busi-ness students (e.g., DeMartino & Barba-to, 2002; Ede et al.; Hills & Barnaby, 1977; Hills & Welsch, 1986; Krueger, Reilly, & Carsrud, 2000; Lissy, 2000; ike baseball and apple pie, owning

a small business is part of the American Dream. Interest in creating and owning a small business has never been greater than it is today. New busi-ness formation in the United States has broken successive records for the last few years, growing at a rate of between 2% and 9% and totaling over half a mil-lion dollars annually (U.S. Small Busi-ness Administration, 2002).

Students also are increasingly choos-ing to start their own businesses both before and during college, as well as post graduation. Some researchers have suggested that the appeal of self-employment and launching a new busi-ness has resulted from continued uncer-tainty about the economy, corporate and government downsizing, and a declin-ing number of corporate recruiters on college campuses (Moore, 2002). More-over, members of Generation X do not perceive launching a business as a risky career path. Described as “the most entrepreneurial generation in history” (Zimmerer & Scarborough, 2002, p. 15), they account for approximately 70% of new business start-ups (Bagby, 1998; Phillips, 1999).

To fuel students’ entrepreneurial ambitions, majors and minors in entre-preneurship have emerged on numerous college and university campuses, signal-ing that specialized majors in tradition-al business disciplines (e.g., marketing,

Interdisciplinary Dimensions in

Entrepreneurship

NANCY M. LEVENBURG PAUL M. LANE

THOMAS V. SCHWARZ

GRAND VALLEY STATE UNIVERSITY GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN

L

Sagie & Elizur, 1999; Sexton & Bow-man, 1983). However, Hynes (1996) advocated that entrepreneurship educa-tion can and should be promoted and fos-tered among nonbusiness students as well as business students. Consequently, if a goal in designing entrepreneurial programs is to assist students within and outside the business school, it is impor-tant to understand the similarities and differences between business school stu-dents and their nonbusiness counterparts.

We examined the entrepreneurial characteristics among interdisciplinary students and the relationships between academic major and interest in entrepre-neurship. The focus was on two groups of students: (a) business majors who wanted to start a new business (business entrepreneurs [BE]) and (b) nonbusiness majors who want to start a business (nonbusiness entrepreneurs [NBE]). In this study, we made no effort to distin-guish between majors within the school of business. In addition, we examined differences between both business and nonbusiness majors who did not want to start a new business (business nonentre-preneurs [BNE] and nonbusiness nonen-trepreneurs [NBNE], respectively). No other study has undertaken such a com-prehensive investigation of entrepre-neurial interest among an interdiscipli-nary student population. These findings should hold interest for business schools that may seek to better understand, serve, and support the entrepreneurial ambitions among students of diverse academic backgrounds.

Review of the Literature

Entrepreneurship as an Academic Discipline

According to Alvarez (1993), interest in entrepreneurship among business dis-ciplines began in the 1940s, with entre-preneurship journals emerging in the 1960s. Amid debates about the legitima-cy of entrepreneurship as a business dis-cipline, entrepreneurship courses were introduced into the realm of business education curricula during the 1980s and subsequently experienced an eight-fold increase in student enrollments over the next decade.

On a national level, interest in entre-preneurship is substantial, as evidenced

by the number of educational institu-tions that (a) have established centers for entrepreneurship, (b) have estab-lished separate entrepreneurship aca-demic departments, (c) currently offer entrepreneurship majors, minors, con-centrations, or special certificate pro-grams, and (d) teach entrepreneurship or similar courses. We found 131 U.S. colleges and universities that support entrepreneurship education in at least one of the first three aforementioned formats and, among those institutions, 92 of them (70.2%) offer a major in entrepreneurship with another 8 (6.1%) offering a minor. Seventy-seven institu-tions offer graduate-level programs in entrepreneurship (58.8%). Finally, the number of schools offering an entrepre-neurship course has grown from a hand-ful 20 years ago to more than 1,000 at present (Hisrich, 1988; Kuratko & Hod-getts, 2004; Solomon & Fernald, 1991). Further recognition of entrepreneur-ship as an academic discipline is evi-denced by the growing number of pro-fessional journals and conferences devoted to the interface between tradi-tional disciplines and entrepreneurship. Additionally, publications such as U.S. News and World Report and Success Magazine have begun to rank the top university entrepreneurship programs as a separate discipline alongside the tradi-tional functradi-tional areas of accounting, finance, management, and marketing.

Student Interest in Entrepreneurship

Early research focused on exploring business students’ interest in entrepre-neurship and entrepreentrepre-neurship courses, and identifying characteristics of entre-preneurs and variables that influence entrepreneurial intent (e.g., Ede et al., 1998; Hatten & Ruhland, 1995; Hills & Barnaby, 1977; Hills & Welsch, 1986; Hutt & Van Hook, 1986; Sexton & Bow-man, 1983). As an example, Hills and Welsch found high interest among busi-ness students in entrepreneurship (52%) and entrepreneurship coursework (80%). More recently, Henderson and Robert-son (1999) collected data from young adults aged 19–25 years who were study-ing entrepreneurship in Scotland, busi-ness students in England, and newly hired employees at a major U.K. bank. Not surprisingly, 67% of those studying

entrepreneurship expressed a desire for self-employment, compared with 5% among the rest.

In 1999, Sagie and Elizur reported the findings from a study conducted among students of small business and students of business and economics. The purpose of their study was to measure the achievement motive among students regarded as having high- and low-entre-preneurial orientations, respectively. Sagie and Elizur found differences among four achievement components tested with small-business students tend-ing to score higher than their business and economics counterparts. Similarly, Krueger and colleagues’ (2000) study to compare two intentions-based models of entrepreneurship activity focused on data collected from undergraduate busi-ness students. DeMartino and Barbato (2002) analyzed gender differences in motivational factors among intending entrepreneurs by studying career percep-tions among Master of Business Admin-istration (MBA) alumni of a U.S. top-tier business school.

To summarize, a review of the litera-ture suggests that there has been grow-ing interest in entrepreneurship among business students and the faculty mem-bers who teach them. To date, the majority of published studies have focused on the identifying characteris-tics (e.g., desire for self-employment), related explanatory factors (e.g., prior family business experience), and demo-graphic differences (e.g., gender, race) of students interested in entrepreneur-ship. Given the proliferation of entre-preneurship courses and curricula offered by business schools in recent years, the lack of research into the entrepreneurial interest and intentions among an interdisciplinary student pop-ulation is surprising. In this study, we attempted to understand interest in entrepreneurship among nonbusiness students and to explore similarities and differences between them and their business school counterparts.

Research Focus

A committee of business and engi-neering faculty members at Grand Val-ley State University, including the co-authors of this article, was charged with exploring the potential for a program in

entrepreneurship in the summer of 2003. The committee was quickly con-fronted with the issue of identifying a target market. At first, it seemed obvi-ous that it should be business and engi-neering students. However, as discus-sion unfolded, considerable anecdotal information emerged about interdisci-plinary students’ interest in starting their own businesses. This led the committee to conclude that, prior to establishing a target market, it was essential to con-duct research to determine levels of interest among the university’s interdis-ciplinary population. Following the goal of assessing the level of interest in new ventures and new venture courses across all university areas, the committee iden-tified four important research questions:

1. To what extent do students across the university population possess the characteristics that are commonly viewed as indicators of entrepreneurial intent?

2. To what extent do students have an interest in innovating new products or services?

3. What is the level and extent of interest in taking new venture courses (i.e., entrepreneurship)?

4. Are there differences between BE and NBE in regard to their neurial intent and interest in entrepre-neurship curricula (Questions 2 and 3 above)?

METHOD

We conducted our study among all students enrolled in courses during the summer of 2003 at Grand Valley State University. The faculty committee developed and refined a questionnaire and pretested it with a convenience sam-ple of 50 students in the university’s stu-dent union. After refining and improv-ing the questionnaire, we posted it on Blackboard (a course management soft-ware; Blackboard, Inc., Washington, DC) and announced it to the population of students enrolled in summer classes (approximately 5,000) via an e-mail message. It should be noted that the uni-versity is rated among “America’s 100 Most Wired Universities” according to Yahoo! Internet Life and is well known for its use of innovative technology, including in-class computer stations,

wireless connectivity in academic build-ings, and Web-based instructional activ-ities. Thus, each student has e-mail access as well as a Blackboard account. The mass e-mail directed students to a site on Blackboard where they could complete the 27-item questionnaire electronically. We offered an incentive for completing the survey; respondents were entered into a drawing for one of six $25 gift certificates redeemable at the university bookstore.

The questionnaire contained 17 state-ments designed to measure interest in entrepreneurship and characteristics of entrepreneurs to which students respond-ed to statements such as “I am a risk taker” using a 5-point Likert scale (1 =

strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The questionnaire also included specific demographic descriptors, such as acade-mic major and minor, acadeacade-mic rank, and gender.

RESULTS

In total, 728 of the approximately 5,000 students enrolled in summer courses responded to the e-mail and completed surveys during a 1-week peri-od in June 2003, representing a response rate of nearly 15%. With respect to aca-demic major and gender, we judged that the sample was representative of the uni-versity’s student population during the regular academic year.

Evidence of Interest in Entrepreneurship

Using a 5-point Likert scale, respon-dents indicated their level of agreement with two statements regarding a career in entrepreneurship: (a) “I would like to work for myself” and (b) “I would like to start my own venture.” With respect to the desire for self-employment, 38.7% (281 of 727) chose strongly agree and 34.9% (254 of 727) chose

somewhat agree. Twenty-three percent (167 of 727) of respondents indicated they strongly agreed with the second statement and 36.2% (263 of 727) said they somewhat agreed with the state-ment. By combining the strongly agree

and somewhat agree responses, we determined that a total of 73.6% (535 of 727) of students indicated that they wanted to be self-employed and 59.1%

(430 of 727) expressed a desire to start their own venture.

These statistics are higher than those reported among U.S. students in nearly all prior studies (e.g., Karr, 1988; Scott & Twomey, 1988), as well as statistics reported by DeMartino and Barbato (2002) on the likelihood of MBA alum-ni of a top-tier business school becom-ing entrepreneurs in the short term. Moreover, they provide a clear indica-tion of overall interest in entrepreneur-ship across the university’s student pop-ulation, both inside and outside of the business school.

Academic Major

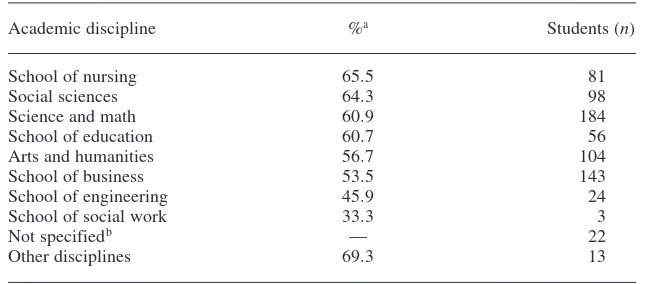

This finding led to analysis of the academic disciplines among those stu-dents who were interested in starting a business. Table 1 shows the percentage of students, according to university aca-demic discipline, who responded some-what agreeand strongly agreeregarding their level of interest in starting a busi-ness. We conducted an analysis of vari-ance (ANOVA) that revealed no statisti-cally significant differences between academic major and interest in starting a business. By inspection, however, the highest levels of interest in starting a business occurred outside the School of Business, namely in the School of Nurs-ing; the School of Social Sciences; the School of Science and Mathematics, which includes biology, biomedical and health sciences, chemistry, computer science and information systems, the School of Engineering, geology, the School of Health Professions, hospitali-ty and tourism management, mathemat-ics, movement science, physmathemat-ics, and sta-tistics; the School of Education; and the School of Arts and Humanities. Perhaps this serves as an indication that those who major in traditional business disci-plines (e.g., marketing, management, accounting, finance) tend to seek employment within specialized depart-ments in larger, more established firms, as opposed to newer, smaller ones.

Chi-square testing failed to reveal a difference between business and non-business majors with respect to the statement “I would like to start my own venture” (see Table 2). We found that both the number and the percentage of NBE were higher than that of BE.

In addition, we found that nearly 6% of students currently owned a business. It is interesting that the highest incidence of business ownership was found within the School of Social Sciences, wherein 7.1% of students sampled (7 of 98) indi-cated that they currently owned busi-nesses, suggesting that entrepreneurship holds appeal for certain segments of the university’s student population.

Characteristics of Entrepreneurs

The survey contained six statements describing characteristics of entrepre-neurs to which students responded using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strong-ly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The six statements included the following: (a) I am a risk taker; (b) I have an idea for a new product or service; (c) I like to tin-ker with ideas for new products; (d) I like to dream about new services; (e) I

have many ideas for possible new busi-nesses or organizations; and (f) I am on the alert for new venture ideas (see Table 3).

First, we conducted an ANOVA to determine if there was a significant dif-ference between BE and NBE. We found significant differences at .001 or higher on all six characteristics, suggesting that there were substantial differences in per-sonal characteristics between students who were intending entrepreneurs and those who were not.

Next, we tested differences among business and nonbusiness students with regard to their level of agreement with each of the six statements. We found sta-tistically significant differences with only two items: “I like to tinker with ideas for new products,”F(703) = 4.035,

p= .045, and “I am on the alert for new venture ideas,”F(703) = 5.309,p= .022. With regard to the former statement, we

found a higher percentage of agreement among nonbusiness majors than among business majors. Further ANOVA testing failed to reveal any significant differ-ences across academic disciplines.

Perceptions of New Venture Opportunities

The questionnaire contained three statements designed to measure stu-dents’ perceptions concerning new ven-ture opportunities and the extent to which they believed they should be exposed to and encouraged to pursue new venture opportunities: (a) There are many opportunities for new businesses in my major field(s) of study; (b) Stu-dents in my discipline should be exposed to new venture opportunities; and (c) University students are encour-aged to pursue new ventures. Students used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) to respond to the statements. The survey results revealed no statistically significant dif-ferences between business and nonbusi-ness students,F(703) = .235,p = .874, on any of the three statements. Indeed, students seemed to perceive opportuni-ties for entrepreneurship across academ-ic disciplines (e.g., “There are many opportunities for new businesses in my major field(s) of study,”F(8) = .432,p= .902. Although the highest mean on this particular item occurred among students enrolled in the School of Social Work (M = 3.33,SD= .58), because of the low sample size (n= 3), these results should be discounted. The next highest means occurred among students enrolled in the School of Nursing (M = 3.28, SD = 1.29), School of Social Sciences (M = 3.24,SD= 1.15) and the School of Busi-ness (M= 3.11,SD= 1.26). Once again, these results suggest that students do not perceive new venture opportunities to lie exclusively within the business school; instead, they are perceived to exist throughout university disciplines.

Interest in Entrepreneurship Courses

The questionnaire contained six statements designed to measure stu-dents’ needs and perceptions concerning support for entrepreneurship within the university environment to which stu-TABLE 1. Student Interest in Starting a Business by Academic Major

Academic discipline %a Students (n)

School of nursing 65.5 81

Social sciences 64.3 98

Science and math 60.9 184

School of education 60.7 56

Arts and humanities 56.7 104

School of business 53.5 143

School of engineering 45.9 24

School of social work 33.3 3

Not specifiedb — 22

Other disciplines 69.3 13

Note. N= 728.

aPercentages shown are for the sum of somewhat agreeand strongly agreeresponses. b22 students did not identify a major.

TABLE 2. Student Interest in Starting a Business, Business Versus Nonbusiness Majors

Strongly Somewhat Somewhat Strongly disagree disagree Neutral agree agree

Student major % n % n % n % n % n

Businessa 11.3 16 14.1 20 21.1 30 35.2 50 18.3 26 Nonbusinessb 9.6 54 12.6 71 17.1 96 36.6 206 24.2 136 Total 9.9 70 12.9 91 17.9 126 36.3 256 23.0 162

Note. N= 705. χ2(4,N= 705) = 3.311 for a test of the null hypothesis that there was no difference between a student’s major (business versus nonbusiness) and level of interest in starting a business. an= 142. bn= 563.

dents responded using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strong-ly agree). Overall, we found a moderate positive correlation (r= .623,p= .000) between students’ interest in starting a new business and interest in taking entrepreneurship courses.

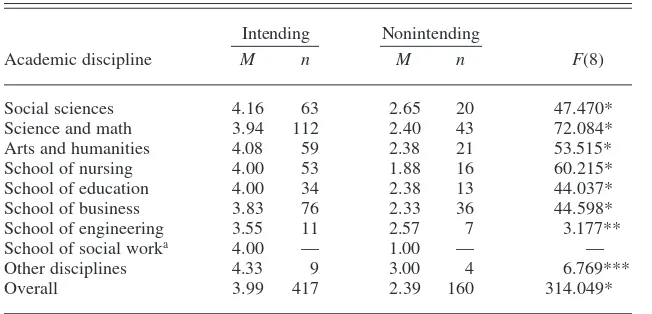

Although there was not a statistically significant difference at the .05 alpha level between business and nonbusiness majors on the item “I would like to take (or would like to have taken) courses about how to start a new venture,” the calculated statistic,F(703) = 3.745,p= .053, would seem to indicate marginal significance. Moreover, the distribution of means (shown in Table 4) suggests that the strongest perceptions of the need for entrepreneurship courses exist within academic disciplines outside of the busi-ness school and engineering, the two disciplines that most frequently offer entrepreneurship courses and curricula. Business and engineering students seem to regard their traditional education as adequate preparation for starting a new business, should they choose to do so.

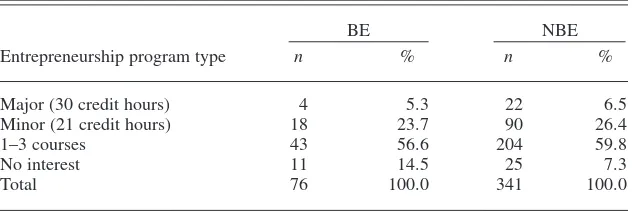

Interest in an Entrepreneurship Program

We filtered the data to focus on those students who were classified as “intend-ing entrepreneurs” (i.e., those who indi-cated strongly agreeor somewhat agree

with respect to level of interest in start-ing a new venture). Students were asked, “If a new venture program is offered to provide the basic skills and applied work, I would be most interested in _____.” Response options included (a) a major (30 credit hours); (b) a minor (21 credit hours); (c) 1–3 courses; and (d) no interest in a new venture course.

The distribution of responses is shown in Table 5. From this, we concluded that the majority of entrepreneurial-oriented students at this particular university wanted to take courses in entrepreneur-ship, although their preference was for fewer courses and a minor over a major. Through cross-tabulation and chi-square testing, we failed to find evidence of an association between major (i.e., business or nonbusiness) and type of entrepre-neurship program desired. Moreover, the data suggest that students view an entre-preneurship curriculum as supporting their already-selected majors in other

disciplines, rather than a stand-alone or second major, as was also suggested by the preference for courses at the 100 and 200 levels.

DISCUSSION

The findings illustrate that a consider-able percentage of students aspire toward entrepreneurship, regardless of their aca-demic discipline. From the data we

gath-ered, it appears as though the entrepre-neurial spirit is alive and well across the university population (e.g., nursing, social sciences, arts and humanities). Indeed, these findings imply that entre-preneurial aspirations, as well as the per-ceived need for entrepreneurship training or education, may be most fervent out-side of the business school.

Consequently, this study suggests that business schools look beyond their TABLE 3. Students’ Entrepreneurial Characteristics by Entrepreneurial Intent

Nonintending Intending (BNE and (BE and NBE) NBNE)

Entrepreneurial characteristic M % M % F(593)

I am a risk taker. 3.78 75.4 3.10 44.8 69.76 I have an idea for a new product

or service. 3.46 55.6 2.16 12.1 166.69

I like to tinker with ideas for new

products. 3.75 66.7 2.37 18.8 206.08

I like to dream about new services. 3.98 77.2 2.57 26.0 234.38 I have many ideas for new

businesses or organizations. 3.67 61.6 1.87 7.3 419.57 I am on the alert for new venture

ideas. 3.51 51.6 2.03 10.9 240.83

Note. N= 595. BE = business major entrepreneurs; NBE = nonbusiness major entrepreneurs; BNE = business major nonentrepreneurs; NBNE = nonbusiness major nonentrepreneurs; Entrepreneuri-al Intent was measured by adding somewhat agreeand strongly agree(or somewhat disagreeand

strongly disagree) responses to the question, “I would like to start my own venture.” Students who were neutral about starting a business were excluded from this analysis.

TABLE 4. Mean Students’ Interest in Entrepreneurship Courses by Entrepreneurial Intent

Intending Nonintending

Academic discipline M n M n F(8)

Social sciences 4.16 63 2.65 20 47.470*

Science and math 3.94 112 2.40 43 72.084*

Arts and humanities 4.08 59 2.38 21 53.515*

School of nursing 4.00 53 1.88 16 60.215*

School of education 4.00 34 2.38 13 44.037*

School of business 3.83 76 2.33 36 44.598*

School of engineering 3.55 11 2.57 7 3.177**

School of social worka 4.00 — 1.00 — —

Other disciplines 4.33 9 3.00 4 6.769***

Overall 3.99 417 2.39 160 314.049*

Note. N= 577. Entrepreneurial intent was measured by adding somewhat agreeand strongly agree

(or somewhat disagreeand strongly disagree) responses to the question, “I would like to start my own venture.” Students who were neutral about starting a business were excluded from this analy-sis.

aBecause n= 3, there were too few cases to conduct this analysis. *p= .000 **p= .094. ***p= .025.

own internal constituents (i.e., majors) if they, and their institutions, seek to serve an interdisciplinary student popu-lation. This may entail reexamining their definition of market scope to eval-uate the roles that they might play in supporting diverse academic majors. Following this, it will be important to develop a curriculum and courses that are flexible enough to foster the dreams of students whose hearts and academic majors lie outside the business school. This would undoubtedly require sub-stantial discussion about admissions standards and course prerequisites, among other things. In this endeavor, Diamond (1998) provided a useful guide for course and curriculum design and assessment.

Limitations

Although the distribution of academic majors and gender of respondents in this study was judged to be representative of this university’s population of students, incoming freshmen were underrepre-sented because of the timing of the study (before new students had arrived on campus). However, there is no reason to believe that their opinions would have been substantially different from other freshmen and sophomores because we failed to find evidence of significant dif-ference by academic rank along items of interest. Nevertheless, to ensure proper representation of the student population during the regular academic year, it would be prudent to readminister the study during the fall or spring semester.

Implications for Future Research

As noted, very little research exists that explores entrepreneurialism among nonbusiness students, yet interest in entrepreneurship among these students is substantial, as is the desire for a limited number of courses to enable them to start and operate new ventures. In designing these courses, it seems imperative that an array of basic entrepreneurship compe-tencies is clearly articulated and woven into learning outcomes and assessment techniques, including (a) identification of the “must-know” topics for aspiring non-business entrepreneurs, both general (e.g., communication, math, critical thinking) and discipline specific (e.g., market analysis, promotion planning); (b) the ways to most effectively support interdisciplinary student learning (i.e., pedagogy); and (c) faculty deployment in designing and teaching entrepreneurship courses to nonbusiness students. Should teaching entrepreneurship be the exclu-sive domain of business school faculty, or should interdisciplinary faculty teams be created to lead curriculum initiatives? Finally, because this study was limit-ed to students enrolllimit-ed in a U.S. mid-western regional university, further research that compares entrepreneurial-ism and interest in entrepreneurship at other types of institutions, or in other countries, would be fruitful.

NOTE

The authors thank Jaideep Motwani, Professor and Chair of Management, and Harinder Singh, Professor and Chair of Economics, at Grand Val-ley State University, Grand Rapids, MI.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Nancy M. Levenburg, Department of Management, Seidman College of Business, Grand Valley State University, 441-C DeVos Cen-ter, 401 W. Fulton Street, Grand Rapids, MI 49504.

E-mail: levenbun@gvsu.edu

REFERENCES

Alvarez, J. L. (1993). The popularization of busi-ness ideas: The case of entrepreneurship in the

1980s. Management Education and

Develop-ment, 24(1), 26–42.

Bagby, M. (1998). Generation X. Success, 45(9), 22–23.

DeMartino, R., & Barbato, R. (2002). An analysis of the motivational factors of intending entre-preneurs. Journal of Small Business Strategy, 13(2), 26–36.

Diamond, R. M. (1998). Designing & assessing courses & curricula: A practical guide. New York: Jossey-Bass.

Ede, F. O., Panigrahi, B., & Calcich, S. E. (1998). African American students’ attitudes toward entrepreneurship education. Journal of Educa-tion for Business, 73, 291–296.

Hatten, T. S., & Ruhland, S. K. (1995). Student attitude toward entrepreneurship as affected by participation in an SBI program. Journal of Education for Business, 70, 224–227. Henderson, R., & Robertson, M. (1999). Who

wants to be an entrepreneur? Young adult atti-tudes to entrepreneurship as a career. Education & Training, 41, 236–245.

Hills, G. E., & Barnaby, D. J. (1977). Future entrepreneurs from the business schools: Inno-vation is not dead. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Council for Small Business (pp. 27–30). Washington, DC: International Council for Small Business.

Hills, G. E., & Welsch, H. (1986). Entrepreneurship behavioral intentions and student independence, characteristics and experiences. In Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research: Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Babson College Entrepreneurship Research Conference (pp. 173–186). Babson Park, MA: Babson College.

Hisrich, R. D. (1988). Entrepreneurship: Past, pres-ent, and future. Journal of Small Business Man-agement, 26(4), 1–4.

Hutt, R. W., & Van Hook, B. L. (1986). Students planning entrepreneurial careers and students not planning entrepreneurial careers: A compar-ative analysis. In Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research: Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Babson College Entrepreneurship Research Conference(pp. 223–224). Babson Park, MA: Babson College.

Hynes, B. (1996). Entrepreneurship education and training: Introducing entrepreneurship into non-business disciplines. Journal of European Industrial Training, 20(8), 10–17.

Karr, A. R. (1988, November). A special news report on people and their jobs in offices, fields and factories. Wall Street Journal,Eastern Edi-tion, p. 1.

Krueger, N. F., Jr., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15, 411–432.

Kuratko, D. F., & Hodgetts, R. M. (2004). Entrepre-neurship(6th ed.). Mason, OH: South-Western.

Lissy, D. (2000). Goodbye b-school. Harvard

Business Review, 78(2), 16–17.

McMullan, W. E., & Long, W. A. (1987). Entre-preneurship education in the nineties. Journal of Business Venturing, 2, 261–276.

TABLE 5. Interest in Entrepreneurship Program Among Those Desiring to Start a Business

BE NBE

Entrepreneurship program type n % n %

Major (30 credit hours) 4 5.3 22 6.5

Minor (21 credit hours) 18 23.7 90 26.4

1–3 courses 43 56.6 204 59.8

No interest 11 14.5 25 7.3

Total 76 100.0 341 100.0

Note. N= 417. BE = business major entrepreneurs; NBE = nonbusiness major entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurial intent was measured by adding somewhat agreeand strongly agreeresponses to the question, “I would like to start my own venture.” Students who were neutral about starting a business were excluded from this analysis.

Moore, B. L. (2002, March 27). Changing classes: The entrepreneurial spirit hasn’t died on busi-ness-school campuses; but it has changed. Wall Street Journal,p. R8.

Phillips, D. (1999, January). Great X-pectations.

Business Start-Ups, 37–43.

Roebuck, D. B., & Brawley, D. E. (1996). Forging links between the academic and business com-munities. Journal of Education for Business, 71, 125–128.

Sagie, A., & Elizur, D. (1999). Achievement motive and entrepreneurial orientation: A

struc-tural analysis. Journal of Organizational

Behavior, 20, 375–387.

Scott, M. G., & Twomey, D. F. (1988). The long-term supply of entrepreneurs: Students’ career aspirations in relation to entrepreneurship. Jour-nal of Small Business Management, 26(4), 1–13. Sexton, D. L., & Bowman, N. B. (1983, August). Determining entrepreneurial potential of stu-dents: Comparative psychological characteris-tics analysis. In Proceedings of the Academy of Management Meeting, Dallas, TX (pp. 55–56). Briarcliff Manor, NY: Academy of Management.

Solomon, G. T., & Fernald, L. W., Jr. (1991).

Trends in small business management and entrepreneurship education in the United States. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 15(3), 25–40.

U.S. Small Business Administration. (2002, May 29). SBA Office of Advocacy small business fre-quently asked questions. Retrieved July 27, 2004, from http://app1.sba.gov/faqs/faqindex .cfm?areaID=24

Zimmerer, T. W., & Scarborough, N. M. (2002).

Essentials of entrepreneurship and small busi-ness management (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.