Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 22:45

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Assessing the Integrity of Web Sites Providing Data

and Information on Corporate Behavior

Josetta Mclaughlin , Deborah Pavelka & Gerald Mclaughlin

To cite this article: Josetta Mclaughlin , Deborah Pavelka & Gerald Mclaughlin (2005) Assessing the Integrity of Web Sites Providing Data and Information on Corporate Behavior, Journal of Education for Business, 80:6, 333-337, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.80.6.333-337

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.80.6.333-337

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 13

View related articles

ith the increase in wider accessi-bility to the Internet, it is becom-ing commonplace for professors, stu-dents, and researchers to use both the data and the findings from Web sites in their work. As this practice by a wider variety of users grows, the ability to judge the integrity of the data and the related findings is also increasing in importance. Considering that the num-ber of Internet hosts grew from 4 in 1969 to 162,128,493 in 2002 (Zakon, 2003), one might even say that the abil-ity to judge the integrabil-ity of the informa-tion available on a Web site is becoming critical. The reason underpinning this concern is evident.

The possible harm that can result from the use of dirty data, misinter-preted information, and incorrect con-clusions can be far-reaching. Unfortu-nately, although some data are reviewed and efforts are made to main-tain data integrity, not all available data and information found on Web sites are reviewed by peers or someone in authority within the discipline (Alexander & Tate, 1999). This places the burden of judging the integrity of Internet-available data on the users.

The ability to judge the integrity of Internet-available data and information is hampered by the lack of a widely accepted set of criteria for this pur-pose. At the present time, one finds

different criteria for judging data and information in the professional and research literature, in policy manuals from various firms, and from govern-ment publications and Web sites. This creates a situation in which the users must select which of the criteria they will use in judging the integrity of the data or information and then consider the following essential components necessary for data and information integrity: (a) the legitimacy of the Web site on which the data and information are located; (b) the integrity of the data and information; and (c) the issues sur-rounding the use of the data and infor-mation. To begin the process, users must first be able to distinguish data from information.

Distinguishing Data From Information

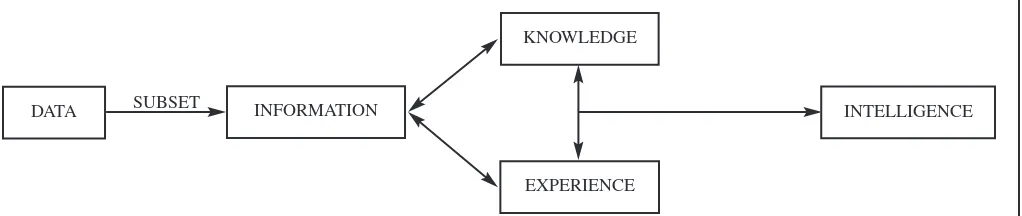

Too often, the terms “data” and “information” are used interchange-ably. In reality,informationis a recon-struction of a subset of data that is rel-evant to a particular decision or question to be answered. The dataare the raw materials, for example, num-bers and facts, that are gathered through the research process and that may be either quantitative or qualita-tive, or a combination of both. For data to become information, the user must determine which data are relevant to the decision. The resulting subset of data is the information that interacts with knowledge and experience to pro-duce intelligence (Figure 1). The level of user knowledge thus plays a major role in moving from information to intelligence and becomes critical to drawing conclusions or making deci-sions (Gal, 2003; Howard & McLaugh-lin, 2003). At this point, a teacher can enhance both the learning and instruc-tion that are taking place in the class-room through the use of data, informa-tion, and knowledge. Similarly, a researcher can create and advance the knowledge base of his or her discipline through effective application of data and information to explain a phenome-non of interest.

Assessing the Integrity of Web Sites

Providing Data and Information on

Corporate Behavior

W

ABSTRACT. A significant trend in higher education evolving from the wide accessibility to the Internet is the availability of an ever-increasing sup-ply of data on Web sites for use by professors, students, and researchers. As this usage by a wider variety of users grows, the ability to judge the integrity of the data, the related find-ings, and the Web site is becoming increasingly important. This article lays the groundwork for developing a set of Generally Accepted Standards of Data Integrity to guide users in evaluating data and information avail-able on Internet Web sites.

JOSETTA MCLAUGHLIN DEBORAH PAVELKA

Roosevelt University Schaumburg, Illinois

GERALD MCLAUGHLIN DePaul University

Chicago, Illinois

Essential Components for Data and Information Integrity

The Legitimacy of the Web Site on Which the Data and Information Are Located

Web sites may contain and make avail-able to the public data housed in databas-es or information that reports rdatabas-esearch results, or both. Regardless of whether the user is considering use of data or of information, trust in the integrity of the data is contingent upon being able to first establish the legitimacy of the Web site. For example, Web sites that are devel-oped and administered by organizations that are associated with governments are generally assumed to be trustworthy. Other Web sites affiliated in some man-ner with government, such as the Organ-isation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2003), are also considered trustworthy. OECD is a non-governmental member agency that administers a site containing substantial coverage of government-generated data for its member countries. In a similar vein, the International Labour Organisa-tion, a specialized agency of the United Nations, provides on its Web site work-force statistics and data covering most countries. The data provided by these organizations are generally assumed to be reliable and valid and are treated much as a researcher would treat official data from government agencies. Much of the data comes, in fact, from official sources. In contrast, Transparency International is a nongovernmental organization that collects and makes available perceptual data on such topics as corruption and bribery. It represents views of individuals from organizations that scrutinize the behavior of national governments and

business. Although this and similar Web sites provide data and information, they are generally classified as advocacy sites. The Web site should contain information clearly identifying the mission of the organization and identifying the purpose of the site as advocacy. Unfortunately, identifying whether the Web site is an advocacy site or some other type of site is complicated by the failure of some non-governmental Web sites to reveal their true purpose. For example, a business site may seem to be an advocacy site. Simi-larly, some advertising sites promote themselves as information sites. A state-ment of the purpose of the Web site may not be sufficient to identify the mission and objectives of the organization, thus complicating the user’s ability to assess whether the Web site is technically an informational site, an advocacy site, or a business site.

Evaluation of sites developed by indi-viduals requires additional considera-tions. When a Web site is developed by an individual as opposed to an agency, integrity is likely present only if the developer is recognized as being knowl-edgeable on the subject and on best prac-tices for data collection. Unfortunately, it is often the case that obtaining informa-tion on a Web site developer is at best dif-ficult. Potential means for assessing the developer may require networking through professional associations and conversations with peers. Search engines may also provide useful information on the developer’s professional activities.

Additional problems that the user may encounter in evaluating the integri-ty of these Web sites include the use of pseudonyms and poor documentation of the source of data and information on the Web site. The user should also be

concerned if there is an absence of information concerning copyright and security, issues which will be addressed hereinafter. In situations in which docu-mentation and information are missing, instructors, researchers, and others use these Web sites and the Web-site con-tents at their own risk.

The Integrity of the Data and Information

Although one should establish the integrity of the Web site, it is not suffi-cient for determining the integrity of the data and information found on the site. The literature on research methodology provides the basis for identification of standards for data and information integrity. At present, there is no unifor-mity in the standards being used by pro-fessionals, businesses, and other Web-site developers for evaluation of the integrity for Web-available data and information. The set of standards identi-fied in this article as criteria for deter-mining the integrity of data and infor-mation on Web sites is a compilation of standards found in the literature and in business and government policy manu-als. The proposed set of standards being suggested will be referred to as the Gen-erally Accepted Standards of Data Integrity (GASDI). These standards are common to those used by both researchers and businesses. We identi-fied several sources as being particular-ly relevant to identifying criteria for assessing Web-available data and infor-mation. The sources used as a starting point for the development of the GASDI are: (a) Alexander and Tate (1999); (b) Statement of Financial Accounting Con-cepts No. 2: Qualitative Characteristics of Financial Information (Financial

DATA INFORMATION

KNOWLEDGE

EXPERIENCE

INTELLIGENCE

FIGURE 1. From data to intelligence.

SUBSET

Accounting Standards Board, 1980); (c) Web-site information such as that pro-vided by Robert R. Harris (1997); and (d) relevant academic publications.

Alexander and Tate (1999) are wide-ly used and cited by libraries that are developing and evaluating Web sites. The criteria they identify for judging the quality of data and information on Web sites include, but are not limited to:

1. Authority: Is the organization or agency recognized as an expert in the field and is it knowledgeable, qualified, and reliable with respect to the subject of interest?

2. Accuracy: How correct and how reliable are the data and information contained on the Web site?

3. Objectivity: Are the data and infor-mation factual and free of personal prej-udice?

4. Currency: Are the data and infor-mation kept current with respect to when collected, published, and revised?

5. Coverage: Is there a clear indica-tion of whether the Web site contains an entire work or only parts of the work that is relevant to the subject of interest? (Alexander & Tate, 1999).

The second source is the Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 2 (SFAC 2): Qualitative Characteristics of Financial Information. This statement is part of the conceptual framework devel-oped by the Financial Accounting Stan-dards Board (1980) for use by the accounting profession. A subset of the characteristics found in SFAC 2 was found to be particularly relevant. It is:

1. Characteristics of decision makers; 2. Understandability;

3. Decision usefulness;

4. Relevance, timeliness, predictive value, and feedback value;

5. Reliability, verifiability, represen-tational faithfulness, and neutrality; and 6. Comparability, including consis-tency (FASB, 1980).

Dr. Robert Harris, a retired professor and full-time author, posted his criteria for evaluating Internet research sources on his personal Web site, www.virtual salt.com. In an article in 1997, he iden-tified three additional criteria that are particularly relevant:

1. Usability: Can the user access the data or information of interest easily and efficiently?

2. Support: Are sources, contact information, corroboration, and docu-mentation supplied?

3. Reasonableness: Are the data and information fair, balanced, objective, reasoned, and absent of fallacies and conflict of interest? (Harris, 1997).

Although Harris’s three criteria may seem to apply to the Web site itself, they also apply to the database and any infor-mational documentation found on the site. For example, users cannot assume data and information integrity in cases in which support in the form of docu-mentation is not made available. In addition, users cannot assume reason-ableness in cases in which the Web site is silent on issues such as those pertain-ing to research methodologies or sam-pling techniques used by the individual doing the data collection.

The recommendations from these authors are consistent with those found in the academic literature on data integrity. Howard, McLaughlin, and McLaughlin (1989) examined data quality in terms of reliability and validity. They examined data reliability, the degree to which an independent but comparable measure would obtain the same results (Churchill, 1979), in terms of stability, objectivity, and internal consistency. In contrast, data validity, the degree to which something does what it is intended to do (Carmines & Zeller, 1979), is examined in terms of internal validity, external validity, and construct validity. Subcategories falling under data reliability and validity span those issues of data integrity expressed by previously mentioned works.

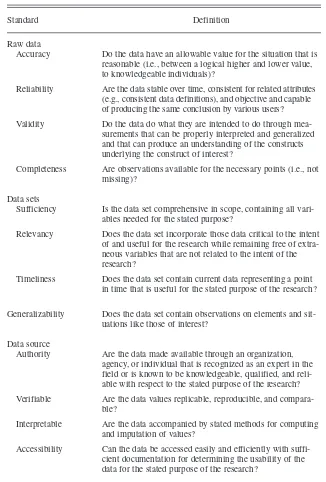

The suggested set of standards for evaluating data and information integrity (GASDI) and brief explana-tions thereof are shown in Table 1. The GASDI consists of three categories containing multiple criteria, all of which are based on the literature and can be used in the evaluation of data and information integrity. Users should be aware that not all criteria will apply equally in all circumstances. The user must ascertain which criteria are more important, given the use for the data and information. For example, there

may be a trade-off between the criteria of timeliness and accuracy, given the purpose for which the data and infor-mation are to be used. Preliminary data may be available on a government Web site that an instructor wants to use in class. The problem is that the instruc-tor knows that the available data are preliminary figures and that the final figures will not be posted on the Web site until after the end of the semester. The dilemma is: Does the instructor use the previous year’s data, which are accurate, or the current year’s data, which are timely?

In addition to evaluating the data and information, the GASDI are useful in addressing a variety of problems that users encounter when using a Web site as a source. These include the eval-uation of summary data when raw data are not available and the identification of problems associated with nonuni-formity of data definitions. Both prob-lems limit comparability between the data and information found on differ-ent Web sites. Even if data and infor-mation are located in the same Web site database, changes in definition over time, the inconsistent use of revised data, inconsistencies in base years, or similar issues hinder the user’s ability to make comparisons between data for different years or for replications of studies. For example, a table posted on June 2003 at the OECD site notes in regard to GDP that “data are broadly consistent with those in the latest issue of the annual OECD national accounts publication. Howev-er, where revised data are available from countries’ submissions, they have been used in this table . . . Various base year, GDP/GNI growth rate” (Gross Domestic Product-Produit Intérieur Brut, 2003). As of 2005, the table ref-erenced above and the data based on 2003 definitions are difficult to locate using the OECD statistics portal.

The Issues Surrounding the Use of the Data and Information

A number of issues surrounding use of data and information can be identi-fied. We address the following in this article: (a) documentation, (b) copy-right, and (c) security.

Copyright

Before one uses sets of data or infor-mation on the Internet, one first has to obtain copyright permission from the provider of the information. A copyright is defined as “[a] bundle of exclusive rights conferred by a government on the creator of original literary or artistic works such as books, articles, drawings, photographs, musical compositions, recordings, films, and computer pro-grams” (Glossary of Web Publishing Terms, 2004). These exclusive rights are granted to the copyright holder, accord-ing to the Berne Convention, for life plus 50 years (Glossary of Web Publishing Terms). More important, when one con-siders using Web site contents, one must recognize that it is a violation of the copyright law to electronically transmit (i.e., copy or download data or informa-tion), display, or distribute materials without the permission of the owner.

It is important to note that registration of an original work is not required for the work to have protection under the copyright laws, including the right to bring action for infringement (Glossary of Web Publishing Terms, 2004). Thus, in cases in which the Web site has no explicit statement concerning the copy-right status of the contents, a potential user must still gain copyright permis-sion from the appropriate source before using the data and information. As a matter of good practice, well-designed Web sites should readily provide copy-right information for users.

Security

Researchers, teachers, and other users of Web-site data and information cannot ignore the security issues surrounding the Internet. The potential for new risks and problems with regard to data and Web-site security is a direct result of the ever-increasing growth of Internet use. This dark side of the Internet is manifested almost daily as new viruses and other forms of attack are perpetrated on the public. According to a report by Weeres (2003), the “number of IT security inci-dents jumped from 52,658 in 2001 to 82,094 in 2002.”

Although security issues are generally associated in the public’s mind with e-Documentation

Use of data that are accessible but that lack proper documentation puts the researcher and teacher at risk. The National Center for Educational Statis-tics (NCES) has made available on its Web site its Handbook of Survey Meth-ods: Technical Report (2003). In its role as both a supplier and producer of data, the agency provides information for users on each of its databases and thus requires consistency in documentation by providers of data (NCES, 2003). The

Appendix shows the information required by providers of NCES databas-es. Researchers and teachers should request that the information be made available for all databases accessible through the Web, especially those using sampling techniques. If this information is not available, then the database and documentation of findings on the Web site should be considered suspect. This places the burden on the producer or Web site administrator to request the informa-tion from the supplier of the data before the data are placed on the Web site.

TABLE 1. Generally Accepted Standards for Data and Information Integrity (GASDI)

Standard Definition

Raw data Accuracy

Reliability

Validity

Completeness

Data sets Sufficiency

Relevancy

Timeliness

Generalizability

Data source Authority

Verifiable

Interpretable

Accessibility

Do the data have an allowable value for the situation that is reasonable (i.e., between a logical higher and lower value, to knowledgeable individuals)?

Are the data stable over time, consistent for related attributes (e.g., consistent data definitions), and objective and capable of producing the same conclusion by various users?

Do the data do what they are intended to do through mea-surements that can be properly interpreted and generalized and that can produce an understanding of the constructs underlying the construct of interest?

Are observations available for the necessary points (i.e., not missing)?

Is the data set comprehensive in scope, containing all vari-ables needed for the stated purpose?

Does the data set incorporate those data critical to the intent of and useful for the research while remaining free of extra-neous variables that are not related to the intent of the research?

Does the data set contain current data representing a point in time that is useful for the stated purpose of the research?

Does the data set contain observations on elements and sit-uations like those of interest?

Are the data made available through an organization, agency, or individual that is recognized as an expert in the field or is known to be knowledgeable, qualified, and reli-able with respect to the stated purpose of the research?

Are the data values replicable, reproducible, and compara-ble?

Are the data accompanied by stated methods for computing and imputation of values?

Can the data be accessed easily and efficiently with suffi-cient documentation for determining the usability of the data for the stated purpose of the research?

commerce, the evidence suggests that researchers and other users of the Internet for research, teaching, and other purpos-es must recognize the potential for mis-chief stemming from security breaches. These may result from either computer viruses or hacker attacks. For example, simply viewing a sight, with no action on the user’s part such as downloading or copying contents, can result in the receipt of a computer virus, a cookie, or tracker on their personal or work computer. With respect to data and information, comput-er viruses can destroy or altcomput-er the con-tents of a Web site. They can also affect the user’s computer by destroying or cor-rupting files, or possibly making the user’s computer unworkable. Oftentimes neither the Web site administrator nor the user are aware of the damage occurring or the source of the problem.

Hacker attacks also pose a variety of dangers to the integrity of contents of the Web site. For example, a hacker can feed his or her ego by replacing or altering data without visible signs to either the owner or user of the Web site. Other motivations for hacking include provid-ing entertainment value for the perpetra-tor and advancing a personal political cause. The problem created by the hack-er that is most critical to the researchhack-er or teacher is the possible alteration of data that invalidates the usability of Web site contents (Tribunella, 2002).

Summary

The Internet and relevant Web sites make secondary data and information readily available to researchers, teachers, and other users thanks to continuing development of user-friendly technology. In addition, the data available on the Web sites are frequently available for down-loading at no fee to any individual who can locate the site. Users who want to incorporate data and information from Web sites into their research and teaching may unknowingly share in the demands for establishment of standards of data integrity. They must help ensure that stan-dards are maintained and that a method-ology is developed for evaluating both the Web site and the data and information made available through the Web site.

There is no single document or source that has established a set of standards that

can be used to ascertain the integrity of a set of data available on a Web site on the Internet. Nevertheless, the literature pro-vides guidance and suggests in total that such a list of standards may already exist. Researchers, teachers, and other users of the Internet have a responsibility to build on these standards to develop a uniform set of criteria for assessing the integrity of the data and information available to them on Web sites.

The set of generally accepted stan-dards proposed herein lays the ground-work for assessing the legitimacy of the Web site on which the data and informa-tion are located and, in turn, the integrity of the data and information. This is only a first step. It provides the basis for the discussion and development of a method-ology that links what is known about data integrity by professions such as account-ing and by researchers to a set of stan-dards that can be used to assess Internet data and information integrity. This methodology, after it has been developed and accepted, should allow all users— researchers, teachers, businesses, the government, and any other user of the Internet—to make better decisions about which data or information can be used in their work in a uniform way. The stan-dards make potential users aware of the fact that they must be concerned about possible alteration or corruption of the data and information and about other potential risks and harms that can occur. Most important, the development of GASDI will provide user benefits other than assessing data integrity by increas-ing the user’s overall awareness of the need for Web-site integrity.

REFERENCES

Alexander, J., & Tate, M. A. (1999). Web wisdom: How to evaluate and create information quality on the Web. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment: Quantitative applica-tions in the social sciences.Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16,64–73.

Financial Accounting Standards Board. (1980). Statement of financial accounting concepts no. 2: Qualitative characteristics of financial informa-tion. Retrieved January 10, 2004, from http://www.fasb.org/pdf/con2.pdf

Gal, I. (2003). Expanding conceptions of statistical literacy: An analysis of products from statistical agencies. Statistics Education Research Journal, 2(1), 3–21.

Glossary of Web Publishing Terms. (2004). Web development guidelines: Resources for creating a Web site at Johns Hopkins. Retrieved May 19, 2004, from http://jhmcis.jhmi.edu/standards/ webguidelines/glossary.cfm

Gross Domestic Product-Produit Intérieur Brut. (2003). Main Economic Indicators. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Retrieved June 9, 2003, from http:// www.oecd.org/EN/statistics/0,,EN-statistics-20-nodirectorate-no-no-no20,00.html

Harris, R. R. (1997). Evaluating Internet research sources. Retrieved July 5, 2003, from http:// www.virtualsalt.com/evalu8it.htm

Howard, R. D., & McLaughlin, G. W. (2003, Sep-tember). Comparison groups. Workshop module presented at the Data and Decisions Workshop, sponsored by the Association for Institutional Research and the Council of Independent Col-leges, Denver, CO.

Howard, R. D., McLaughlin, G. W., & McLaughlin, J. S. (1989). Bridging the gap between the data base and user in a distributed environment. CAUSE/EFFECT,12(2), 19–25.

National Center for Educational Statistics. (2003). Handbook of survey methods: Technical report. Retrieved January 10, 2004, from http://nces.ed. gov/pubs2003/2003603.pdf

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD. Retrieved June 9, 2003, from http://www.oecd.org

Tribunella, T. (2002). Twenty questions on e-com-merce security. CPA Journal,72(1), 60–63. Weeres, H. (2003). Beating hackers to the patch.

Computer Emergency Response Team [CERT] Coordination Center, Carnegie Mellon Universi-ty, NetSupport Solutions. Retrieved May 19, 2004, from http://www.ebizq.net/topics/sys-tems_management/features/3407.html?pp=1) Zakon, R. H. (2003). Hobbes’ Internet timeline

1993–2003. Retrieved July 18, 2003, from www.zakon.org/robert/Internet/timeline

APPENDIX

Information to be Provided for Databases

Overview Purpose Components Periodicity Uses of data Key concepts Survey design

Target population Sample design Assessment design

Data collection & processing Reference Dates