Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 18:55

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Faculty salary as a predictor of student outgoing

salaries from MBA programs

Karla R. Hamlen & William A. Hamlen

To cite this article: Karla R. Hamlen & William A. Hamlen (2016) Faculty salary as a predictor of student outgoing salaries from MBA programs, Journal of Education for Business, 91:1, 38-44, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1110552

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1110552

Published online: 01 Dec 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 7

View related articles

Faculty salary as a predictor of student outgoing salaries from MBA programs

Karla R. Hamlenaand William A. Hamlenb

aCleveland State University, Cleveland, Ohio, USA;bState University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York, USA

ABSTRACT

The authors’purpose was to investigate the predictive value of faculty salaries on outgoing salaries of master of business administration (MBA) students when controlling for other student and program variables. Data were collected on 976 MBA programs using Barron’sGuide to Graduate Business Schools

over the years 1988–2005 and the Princeton Review’sThe Best 295 Business Schools2014 edition. A

hierarchical linear regression analysis was conducted with student and program characteristics as control variables, faculty salary as the predictor variable, and average outgoing salary as the dependent variable. In general, higher faculty salaries were associated with higher starting salaries for MBA students upon graduation. Potential explanations and limitations are discussed.

KEYWORDS

faculty salary; MBA students; utgoing salary; regression

With rising numbers of graduate school applicants despitefluctuations in the economy ( Graduate Manage-ment Admission Council [GMAC], 2012), faculty and administrators in business schools continually seek to identify factors that most impact student outcomes upon graduation to offer competitive programs of high quality. There is disagreement, however, over which factors are indicative of the quality of a master of business adminis-tration (MBA) program, and whether these translate to improved career-related outcomes upon graduation. Stu-dent characteristics have been widely used for measuring program quality, but these may be more highly indicative of the rigor of admissions than of the program itself. It has been suggested that economic attainment upon grad-uation may be a better outcome to consider when look-ing for ways to assess and improve MBA programs (Tracy & Waldfogel,1997). In addition, the role of fac-ulty salary in student outcomes has not been as widely investigated as some other student and program varia-bles. The purpose of this study was to determine student, faculty, and program characteristics that predict the starting salary of graduates from MBA programs and, in particular, the relationship between faculty salary and outgoing starting salary, when controlling for other stu-dent and program characteristics. The research questions to be addressed are the following:

Research Question 1 (RQ1): Do faculty salaries predict outgoing salary of MBA program graduates, above and beyond the predictive value of other program and student variables?

RQ2: Do these relationships differ based on quality of the students entering the program, with quality measured by incoming student GMAT (Graduate Management Admissions Test) scores?

Significance

Previous research addressing the assessment of MBA pro-grams has pointed toward the use of economic attainment upon graduation as a more viable outcome variable than most student characteristics for evaluation and measurement of MBA programs. As recommended by previous research-ers, in the present study the outcomes of MBA programs were measured using the outgoing salary of graduates. A pre-existing and publicly available data set was used, allowing for a large sample. This study adds to the research base in this field by incorporating a larger sample size than most previous research, by utilizing a dependent variable that bet-ter captures workplace outcomes rather than academic suc-cess within the program itself, and also by highlighting the predictive value of faculty salaries when controlling for many other potential factors relating to outgoing student salaries.

Related literature

Justification for evaluating an MBA program through outgoing salaries

One challenge in evaluating MBA programs is that the quality of students admitted to top programs can skew

CONTACT Karla R. Hamlen k.hamlen@csuohio.edu Cleveland State University, Department of Curriculum & Foundations, 2121 Euclid Avenue,

Cleveland, OH 44115, USA.

© 2016 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

2016, VOL. 91, NO. 1, 38–44

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1110552

the outcome variables. While student characteristics such as scores on the GMAT and prior grade point average (GPA) may predict success in an MBA program (Kass, Grandzol, & Bommer, 2012; Siegert, 2008; Talento-Miller & Rudner,2008), they do not necessarily predict actual business workplace competencies such as deci-sion-making and leadership skills (Kass et al.,2012).

The precedent for measuring career success of busi-ness school graduates by their salaries dates at least as far back as the 1970s (e.g., Gutteridge, 1973). Tracy and Waldfogel (1997) posited that evaluation of the quality of MBA programs is better done through graduate per-formance in the market—outgoing salaries—than through subjective opinions or incoming student charac-teristics. Ray and Jeon (2008) also named MBA graduate earnings a measure of success of an MBA program, based on their finding that rankings are often a reflection of inputs (student and program characteristics). They dem-onstrated that some lower-ranked programs utilize their resources more efficiently to result in higher outgoing student salaries, in relation to incoming student charac-teristics and program resources, than their higher-ranked counterparts.

Predictor and control variables

Faculty salary was the primary predictor of interest in this study, and several other variables were included as control variables, based on the possibility that they may also be predictors of MBA program outcomes, as dem-onstrated in previous studies.

Faculty salary

Research has shown that higher education institutions tend to use faculty salary to reward faculty activities that enhance university prestige, such as research, obtaining grants, and particularly publication in top-tier journals. This appears to be equally true regardless of whether the institution’s mission emphasizes teaching or research (Braxton, Luckey, & Helland, 2002; Fairweather, 2005; Gomez-Mejia & Balkin, 1992; Melguizo & Strober,

2007). Faculty rank has also been shown to be directly proportional to faculty research productivity (White, James, Burke, & Allen,2012), and those of a higher fac-ulty rank are more likely to have more experience and seniority than their counterparts at other ranks (Strath-man,2000). Furthermore, it has been suggested that fac-ulty quality is directly related to research grant performance, and that obtaining research grants not only increases faculty salaries but also allows for more university resources in the form of equipment, person-nel, and technology (Mohr,1999). In general, faculty feel that a greater value and recognition is placed on research

achievements as opposed to teaching achievements (Alpay & Verschoor, 2014). Interestingly, higher base faculty salaries tend to be related to spending fewer hours in the classroom teaching among comprehensive and doctoral granting institutions, with higher salary returns due to greater teaching hours being a rare occurrence in any type of institution (Fairweather,2005).

There is little research exploring connections between faculty quality or faculty salaries and MBA program out-comes. Student ratings of faculty have been significantly related to the students’likelihood of recommending their MBA program to others (Bruce & Edgington,2008), and there is a positive relationship between the value of the MBA degree—partially measured by expected outgoing salaries of graduates—and student likelihood of recom-mending the program (Bruce & Edgington, 2008). The present study is an investigation of the predictive value of faculty salary when value is assessed by outgoing sal-ary of graduates of an MBA program. Faculty salsal-ary is particularly valuable as a predictor variable when, as in many cases, other measures of faculty quality, such as research productivity and prestige, are unavailable.

GMAT and GPA scores

The GMAT is generally used as the primary admissions exam required for business schools, designed to function as an aptitude test for business school. Many researchers have provided evidence that the GMAT successfully pre-dicts success in MBA programs, when success is measured by academic performance (Koys,2010; Kuncel, Crede, & Thomas, 2007; Oh, Schmidt, Shaffer, & Le, 2008), and even more so when combined with undergraduate grade point average to predict academic performance in an MBA program (Braunstein, 2002; Talento-Miller & Rud-ner,2005; Truell, Zhao, Alexander, & Hill,2006).

Gender

There has historically been a gender gap within graduate business programs, where men tend to score higher than women in entrance measures. Hancock (1999) noted gender differences in GMAT scores among MBA stu-dents, but no difference in academic achievement, while others assert that gender does not significantly predict academic performance in an MBA program (Truell et al., 2006; Yang & Lu, 2001). This issue requires the inclusion of gender as a control variable in most analyses of academic performance.

Age

In most previous research, age has been included as a control variable but has not generally been shown to be related to academic performance in an MBA program (e.g., Wright & Palmer, 1997; Yang & Lu, 2001). Most JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS 39

studies, however, measure performance through aca-demic achievement within the program. As this study measures performance through outgoing salaries upon graduation, age becomes more important because it may be related to work experience and salary expectations.

Other control variables

Other variables that were hypothesized to play a role in differences in program outcomes were whether the school was public or private, numbers of full-time and part-time faculty, numbers of full-time and part-time students, percent of international students, percent of statistically underrepresented minority students, and cost of the school.

Research methodology

Data source

A sample of 976 MBA programs were selected from Bar-ron’sGuide to Graduate Business Schools(Miller & Pol-lack, 2007) over the span of years 1988–2005 and from the Princeton Review’s The Best 295 Business Schools 2014 edition ( Princeton Review,2013). All of the schools for which the guide provided complete information for the variables in this study were included in the analysis. Of the resulting sample, approximately 38% were public, and 62% private. Statistics were reported by administra-tors from each business school. Validity of the data was investigated by comparing faculty salaries in the sample to salary data collected by national and international organizations. For the year 1995, business faculty full professor salaries in the sample did not differ signifi -cantly from the mean provided by the College University and Personnel Association (Howe,1996) for either pub-lic universities,t(95)D0.928,p>.05 or for private

uni-versities,t(54)D ¡1.093,p>.05. For the year 2013, the

mean faculty salary of the sample data was not signifi -cantly different from the corresponding mean reported by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (2013),t(28)D 1.401,p> .05, supporting the

validity of the data.

Variables

Data were recorded for each school on the following var-iables: Average faculty salary (full professor in that pro-gram), GMAT and undergraduate GPA scores upon entry to the program, average student age in the MBA program, average outgoing salary of MBA graduates, percent of international students, percent of statistically underrepresented minority students, percent of women, number of full-time faculty, number of part-time faculty,

number of full-time students, number of part-time stu-dents, tuition cost, and total cost. To ensure normality of the data, several variables were transformed to the natu-ral log of the original data. This was done for each of the continuous, or nondiscrete, variables. Additionally, fac-ulty salaries were adjusted for cost of living based on consumer price index for that year. Faculty salaries were measured by the average salary of a full professor in that program, for consistency of comparisons across institutions.

Findings

A linear regression was performed with average outgoing salary (natural log) as the dependent variable and all of the aforementioned predictor variables as independent and control variables. Multicollinearity statistics were examined, and it was apparent that tuition cost was highly related to several other variables, so this was removed from the analysis. Additionally, the relation-ships between numbers of full time and part time faculty and numbers of full time and part time students created multicollinearity so, of these, only numbers of full time faculty and numbers of part time students were included in the analysis. After these corrections were made, all VIF values were under 2.5, and all tolerance levels were over 0.4, so multicollinearity was not a problem. Once these were resolved, a hierarchical regression was per-formed to determine the extent to which faculty salaries predict outgoing student salary from MBA programs, above and beyond the student characteristic and school characteristic variables. The first step of the model included all student characteristic variables (GMAT scores, GPA, age, percent international students, women, minority students, and number of part-time students). The second step of the model added in school character-istics (public or private, number of full time faculty). The final step added in the primary independent variable of interest, faculty salary.

Student and school characteristic variables

The first step of the model, with student characteristic variables as independent variables (GMAT scores, GPA, age, percent international students, women, minority students, and number of part-time students), was signifi -cant, F(7, 632)D 67.937,p< .001 (R2 D.432, adjusted R2D.426). This indicates that the model was a goodfit and that approximately 43% of the variability in outgo-ing salaries of MBA graduates can be explained by varia-tion in the student characteristic variables included in the model. The second step of the model, adding school characteristics (public or private, number of full-time

faculty) into the model as additional independent varia-bles, was also significant, F(9, 632) D 56.779, p< .001

(R2 D .451, adjusted R2 D .443). While this model still significantly predicts variability in outgoing salaries from MBA programs, the school characteristic variables added little explanatory value above and beyond that of the stu-dent characteristics from thefirst step.

Faculty salaries

In the third andfinal step, the faculty salaries variable was added to the regression. This step was also signifi -cant,F(10, 632)D175.701,p<.001(R2D.739, adjusted R2D.734). SeeTable 1for complete results. From Step 2 to Step 3, the explanatory value increased from approxi-mately 45% to approxiapproxi-mately 74% of the variation in outgoing salaries from MBA programs being explained by the variables in the model. This shows that faculty sal-aries significantly predict variation in outgoing salaries from MBA programs, above and beyond the included student and school characteristic variables, and adding the variable faculty salaries contributes substantially more explanatory value to the model (DR2D.288).

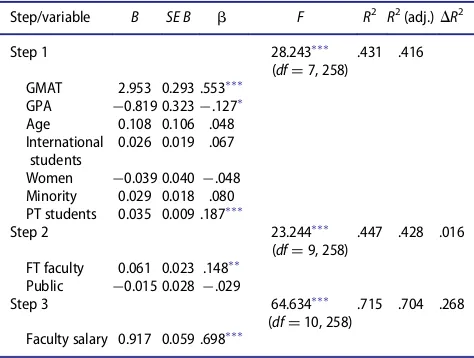

Since several of the variables may be related to the rank of the school and the type of students it attracts, the regression was conducted again, with the data sepa-rated by GMAT scores. The median GMAT score for all of the schools was 560, so the schools were divided into two groups: those with average GMAT scores greater than 560, and those with average GMAT scores less than or equal to 560. The result of the regression analy-sis for schools that have average GMAT scores greater than 560 can be found in Table 2. Overall, the three steps of the regression model were all significant, with each step adding proportionally similar explanatory

value to corresponding steps of the model including all schools. In general, higher average full professor salaries are associated with higher starting salaries for MBA stu-dents upon graduation,bD15.749,p<.001.

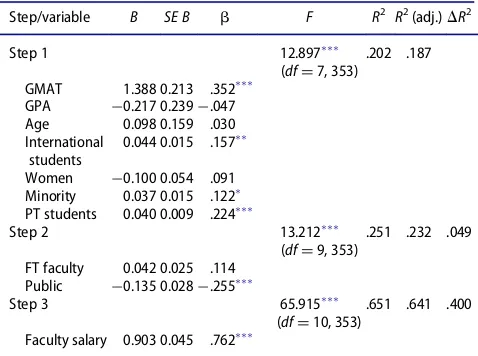

The result of the regression analysis for schools that have average GMAT scores of less than or equal to 560 can be found in Table 3. Overall, the three steps of the regression model were significant. Among MBA pro-grams with an average GMAT score of less than or equal to 560, the primary predictor of outgoing salaries is aver-age faculty salary. In agreement with the previous two analyses, faculty salary is positively associated with stu-dent outgoing salaries,bD0.698, p<.001.

As an additional check to ensure that the significance of faculty salary was not related to tuition of the institu-tion, universities were separated into two groups based on the median natural log of the reported total cost of attending, with total cost adjusted based on Consumer Price Index in the same manner as faculty salaries. For both groups, the overall regressions were significant and there was a positive relationship between faculty salary and outgoing salary: higher cost group, bD 0.725,p<

.001; lower cost group,bD0.690,p<.001.

Discussion

Faculty salary

The relationship between average faculty salary and out-going student salary is the primarily relationship of inter-est, and it was shown to be the stronginter-est, both in terms of level of significance, and also because it was recurrent in each analysis. As faculty salaries were adjusted uniformly based on Consumer Price Index for each year, faculty salary does not reflect a difference based on cost of living,

Table 1.Hierarchical regression analysis predicting outgoing sal-aries of MBA students.

Step/variable B SE B b F R2 R2(adj.)DR2

Step 1 67.937

(dfD7, 622)

.432 .426 GMAT 1.805 0.117 .569

GPA ¡0.389 0.192¡.069

Age 0.137 0.091 .046 International

students

0.041 0.011 .117

Women 0.005 0.033 .005 Minority 0.046 0.011 .126

PT students 0.039 0.007 .189

Step 2 56.779

(dfD9, 622)

.451 .443 .019 FT Faculty 0.038 0.017 .092

Public ¡0.087 0.020¡.147

Step 3 175.701

(dfD10, 622)

.739 .734 .288 Faculty salary 0.924 0.035 .749

p

<.05.p<.01.p<.001. Dependent variable: average salary (Ln).

Table 2.Schools that have average GMAT scores greater than 560.

Step/variable B SE B b F R2 R2(adj.)DR2

Step 1 28.243

(dfD7, 258)

.431 .416 GMAT 2.953 0.293 .553

GPA ¡0.819 0.323¡.127

Age 0.108 0.106 .048 International

students

0.026 0.019 .067 Women ¡0.039 0.040¡.048

Minority 0.029 0.018 .080 PT students 0.035 0.009 .187

Step 2 23.244

(dfD9, 258)

.447 .428 .016 FT faculty 0.061 0.023 .148

Public ¡0.015 0.028¡.029

Step 3 64.634

(dfD10, 258)

.715 .704 .268 Faculty salary 0.917 0.059 .698

p

<.05.p<.01.p<.001. Dependent variable: average salary (Ln). JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS 41

and based on the final analysis, faculty salary also does not reflect a difference based on tuition collected by the institution. Determining the reason for this relationship is not straightforward, but previous research supports various possibilities: Higher faculty salaries may be indic-ative of greater faculty research productivity (see Fair-weather,2005; Melguizo & Strober,2007), greater faculty expertise/quality (Ehrenberg, McGraw, & Mrdjenovic,

2006), or motivation (Comm & Mathaisel, 2003), or some other combination of these factors.

The predominant finding from research on faculty salaries is that faculty salaries, beyond differences in cost of living, relate most powerfully to research productivity, including publications and obtaining research grants (Braxton et al., 2002; Fairweather,2005; Gomez-Mejia & Balkin, 1992; Melguizo & Strober, 2007; White et al.,

2012). Furthermore, it has been suggested that faculty quality is directly related to research grant performance, and that obtaining research grants not only increases fac-ulty salaries but also allows for more university resources in the form of equipment, personnel, and technology (Mohr,1999). In general, faculty members at all types of institutions tend to feel that a greater value and recogni-tion is placed on research achievements as opposed to teaching achievements (Alpay & Verschoor,2014). Inter-estingly, rather than rewarding teaching, higher base fac-ulty salaries tend to be related to spending fewer hours in the classroom teaching among comprehensive and doctoral granting institutions, with higher salary returns due to greater teaching hours being a rare occurrence in any type of institution (Fairweather,2005).

Based on this evidence, one interpretation of the results of the present study is that outgoing salaries from an MBA program are strongly related to the publication record of the faculty in that program. In other words,

MBA programs with higher paid senior faculty are more likely to have faculty with strong publication records, thus giving the students’ MBA degrees greater prestige and higher value. Higher research productivity could be evidence of greater notoriety, expertise, or greater levels of university support, among other possibilities. While previous research supports these concepts, and use of the control variables rule out that faculty salaries are purely indicative of program competitiveness and selectivity, it is also possible that the faculty salaries variable is captur-ing another variable that was not measured in this analy-sis, or a combination of other variables. Possibilities include type of MBA program, location, and networking connections of the institution, faculty, and students.

Limitations

While separating schools based on cost confirms the pos-itive relationship between faculty salary and outgoing student salary, each method of dividing the data comes with its own set of limitations. For example, some schools use subsidies to recruit better students who can-not afford the tuition, and administrators’self-reports on total tuition are not always valid. This touches on a larger limitation to this study, which is that it relies on data reported by administrators, which is not always valid or reliable (e.g., Hossler, 2000). While faculty salaries were shown to be valid based on comparisons to outside data sources, it is not possible to verify all of the data provided in these guidebooks. Other limitations to this study include lack of additional variables by which to analyze the sample, such as type of MBA program and connec-tions between faculty and businesses, and the possibility of confounding variables that were not considered in the analysis.

Conclusions

There have been several studies investigating the quali-ties of an MBA program that relate to student achieve-ment and performance as measured by GPA (Kass et al.,

2012; Siegert, 2008; Talento-Miller & Rudner, 2008). There have been fewer studies investigating factors of an MBA program that relate to the outcome of salary upon graduation from the program. This study adds to litera-ture by using the outcome variable of outgoing salary, by focusing on a less-researched predictor—faculty salary, and by utilizing a public data set, thereby employing a large sample size that includes many different programs across the United States.

The primary finding of this study was a significant, positive relationship between faculty salary in an MBA program and student salary upon graduation

Table 3.Schools that have average GMAT scores less than or equal to 560.

Step/variable B SE B b F R2 R2(adj.)DR2

Step 1 12.897

(dfD7, 353)

.202 .187 GMAT 1.388 0.213 .352

GPA ¡0.217 0.239¡.047

Age 0.098 0.159 .030 International

students

0.044 0.015 .157

Women ¡0.100 0.054 .091

Minority 0.037 0.015 .122

PT students 0.040 0.009 .224

Step 2 13.212

(dfD9, 353)

.251 .232 .049 FT faculty 0.042 0.025 .114

Public ¡0.135 0.028¡.255

Step 3 65.915

(dfD10, 353)

.651 .641 .400 Faculty salary 0.903 0.045 .762

p

<.05.p<.01.p<.001.

Dependent variable: average salary (Ln).

from the program. This relationship was significant when including all programs in the sample, as well as both for programs with higher average GMAT scores and for programs with lower GMAT scores when split into separate groups. This was an exploratory correlational study, so cause-effect relationships can-not be established. While there are several possible explanations for this relationship, it highlights the importance of faculty in MBA programs. According to previous research, programs that value faculty more are also more likely to support faculty research efforts, which can bolster a program’s reputation, thus increasing employer demand for the program’s graduates (Kranzler, Grapin, & Daley, 2011). Addi-tionally, researchers have determined that faculty research productivity is significantly related to student learning, providing another link between faculty qual-ity and student outcomes (Galbraith & Merrill,2012).

Recommendations

Because this research is correlational, explanations behind significant relationships are purely theoretical, and based on previous research. While further research should be done to confirm these findings and to delve into the underlying causes of these relationships, it appears that higher faculty salary, possibly indicative of faculty quality and support from the university, is indeed related to higher student salary attainment upon gradu-ating from MBA programs. This does not provide proof that paying faculty more, or valuing faculty and their productivity more highly, would result in higher outgo-ing salaries for students, but careful consideration of fac-ulty pay and motivation is warranted. Future research would add to thesefindings by including additional fac-tors, such as the specific types of MBA programs being assessed, looking into levels of formal and informal net-working connections between MBA faculty and employ-ers, and by utilizing different analyses that will allow for the incorporation of school reputations and rankings as independent or control variables.

Collecting valid and reliable data on MBA pro-grams and students can be challenging. Researchers would benefit if programs would collect uniform data from students regarding these variables as well as additional variables such as prior work experience and career goals. The validity of administrator-reported data has been called into question (Hossler,

2000), so either verifying the validity and reliability of these data to a greater extent or utilizing addi-tional data sources may be beneficial in understand-ing these relationships more thoroughly. Despite the limitations of the data sources, these findings point

to important issues for consideration among MBA program faculty and administrators. While the focus has traditionally been on student success within a program, this study, among others, points to the importance of considering career and fi nan-cial factors upon graduation from the program. Tra-ditionally, there has been an emphasis on admitting the best students to programs to bolster the success rate of the program. It is important for coordinators and administrators to consider additional factors other than student characteristics, such as valuing faculty research achievement and support, when looking for ways to foster a successful program.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hamlen passed away on April 15, 2015.

References

Alpay, E., & Verschoor, R. (2014). The teaching researcher: Faculty attitudes toward the teaching and research roles. European Journal of Engineering Education,39, 365–376. Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. (2013).

Business school data trends 2013. Retrieved from http:// www.aacsb.edu/~ /media/AACSB/Publications/data-trends-booklet/2013-data-trends.ashx

Braxton, J. M., Luckey, W., & Helland, P. (Eds.). (2002). Insti-tutionalizing a broader view of scholarship through Boyer’s four domains. InASHE-ERIC higher education report(Vol. 292). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Wiley Periodicals. Braunstein, A. W. (2002). Factors determining success in a

graduate business program. College Student Journal, 36, 471–477.

Bruce, G., & Edgington, R. (2008). Factors influencing word-of-mouth recommendations by MBA students: An exami-nation of school quality, educational outcomes, and value of the MBA.Journal of Marketing for Higher Education,18, 79–101.

Comm, C. L., & Mathaisel, D. F. X. (2003). A case study of the implications of faculty workload and compensation for improving academic quality.International Journal of Edu-cational Management,17, 200–210.

Ehrenberg, R. G., McGraw, M., & Mrdjenovic, J. (2006). Why do field differentials in average faculty salaries vary across universities?Economics of Education Review,25, 241–248. Fairweather, J. S. (2005). Beyond the rhetoric: Trends in the

relative value of teaching and research. Journal of Higher Education,76, 401–422.

Galbraith, C. S., & Merrill, G. B. (2012). Faculty research pro-ductivity and standardized student learning outcomes in a university teaching environment: A Bayesian analysis of relationships.Studies in Higher Education,37, 469–480. Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Balkin, D. B. (1992). Determinants of

faculty pay: An agency theory perspective. Academy of Management Journal,35, 921–955.

Graduate Management Admission Council (GMAC). (2012). 2012 application trends survey report. Retrieved from http:// JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS 43

www.gmac.com/» /media/Files/gmac/Research/admissions- and-application-trends/2012-application-trends-survey-report.pdf.

Gutteridge, T. G. (1973). Predicting career success of graduate business school alumni.The Academy of Management Jour-nal,16, 129–137.

Hancock, T. (1999). The gender difference: Validity of stan-dardized admission tests in predicting MBA performance. Journal of Education for Business,75, 91–93.

Hossler, D. (2000). The problem with college rankings.About Campus,5, 20–24.

Howe, R. D. (1996).Salary-trend studies of faculty for the years 1992–1993 and 1995–1996 in the following academic disci-plines/majorfields: Accounting, art, general…geology.

Col-lege and University Personnel Association. Washington, DC: Appalachian Consortium, Inc.

Kass, D., Grandzol, C., & Bommer, W. (2012). The GMAT as a predictor of MBA performance: Less success than meets the eye.Journal of Education for Business,87, 290–295.

Koys, D. (2010). GMAT versus alternatives: Predictive validity evidence from central Europe and the middle east.Journal of Education for Business,85, 180–185.

Kranzler, J. H., Grapin, S. L., & Daley, M. L. (2011). Research productivity and scholarly impact of APA-accredited school psychology programs: 2005–2009. Journal of School Psy-chology,49, 721–738.

Kuncel, N. R., Crede, M., & Thomas, L. L. (2007). A meta-anal-ysis of the predictive validity of the Graduate Management Admissions Test (GMAT) and undergraduate grade point average (UGPA) for graduate student academic perfor-mance.Academy of Management Learning and Education, 6, 51–68.

Melguizo, T., & Strober, M. H. (2007). Faculty salaries and the maximization of prestige.Research in Higher Education,48, 633–667.

Miller, E., & Pollack, N. F. (2007).Barron’s guide to graduate business schools(15th ed.). Hauppage, NY: Barron’s Educa-tional Series, Inc.

Mohr, L. B. (1999). The impact profile approach to policy merit.Evaluation Review,23, 212–249.

Oh, I., Schmidt, F. L., Shaffer, J. A., & Le, H. (2008). The Graduate Management Admission Test (GMAT) is more

valid than we thought: A new development in meta-analysis and its implications for the validity of the GMAT. Academy of Management Learning and Educa-tion,7, 563–570.

Princeton Review. (2013). The best 295 business schools(2014 ed.). Framingham, MA: TPR Education IP Holdings. Ray, S., & Jeon, Y. (2008). Reputation and efficiency: A

non-parametric assessment of America's top-rated MBA pro-grams. European Journal of Operational Research, 189(1), 245–268.

Siegert, K. O. (2008). Executive education: Predicting student success in Executive MBA programs.Journal of Education for Business,83, 221–226.

Strathman, J. G. (2000). Consistent estimation of faculty rank effects in academic salary models.Research in Higher Edu-cation,41, 237–250.

Talento-Miller, E., & Rudner, L. M. (2005). GMAT validity study summary report for 1997 to 2004. GMAC research reports. McLean, VA: Graduate Management Admission Council.

Talento-Miller, E., & Rudner, L. M. (2008). The validity of Graduate Management Admission Test scores: A summary of studies conducted from 1997 to 2004. Educational and Psychological Measurement,68, 129–138.

Tracy, J., & Waldfogel, J. (1997). The best business schools: A market-based approach.Journal of Business,70, 1–31. Truell, A. D., Zhao, J. J., Alexander, M. W., & Hill, I. B. (2006).

Predicting final student performance in a graduate business program: The MBA. Delti Pi Epsilon Journal,48, 144–152.

White, C. S., James, K., Burke, L. A., & Allen, R. S. (2012). What makes a “research star”? Factors influencing the research productivity of business faculty. International Journal of Productivity & Performance Management, 61, 584–602.

Wright, R. E., & Palmer, J. C. (1997). Examining performance predictors for differentially successful MBA students. Col-lege Student Journal,31, 276.

Yang, B., & Lu, X. R. (2001). Predicting academic perfor-mance in management education: An empirical investi-gation of MBA success. Journal of Education for Business, 77(1), 15–20.