Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI

TANJUNGPINANG, KEPULAUAN RIAU] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 17:31

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Using Teams for Class Activities: Making Course/

Classroom Teams Work

James A. Buckenmyer

To cite this article: James A. Buckenmyer (2000) Using Teams for Class Activities: Making Course/Classroom Teams Work, Journal of Education for Business, 76:2, 98-107, DOI: 10.1080/08832320009599960

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320009599960

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 97

View related articles

Making

Using Teams for Class Activities:

CourseClassroom

Teams Work

JAMES A. BUCKENMYER

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Southeast Missouri State University

Cape Girardeau, Missouri

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ecause of the increased emphasis

B

on and use of teams in organiza- tions of all types, university professors, especially those in colleges of business and related areas, have been using teams in various ways in their classes. Such in- class use of teams has been strongly endorsed and supported by external organizations as well as alumni. Both organizations and alumni repeatedly indicate that the increased use of teams in the “real world” has increased stu- dents’ need for exposure and experience with teams. Therefore, the increased use of teams for classkourse projects, par- ticularly long-term, fairly complex ones, is highly justified.However, problems often arise with team use in the classroom. Often the stu- dents have bad experiences or extensive complaints about using teams. Fre- quently, the announcement that there will be a team project is received with moans, complaints, or other indications of displeasure. In one informal class-

room inquiry, 4 class members indicated

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

that they had had good team experiences in classes, but 17 reported negative ones. Other classes responded similarly to the same inquiry.

When asked for the reason(s) for the negative reactions toward teams, the students freely expressed themselves. They felt that teams were unproductive or unpopular for the following reasons:

90

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

JournalzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Educationfor

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

BusinessABSTRACT. The negative experi- ences that students often have with course team assignments can sour their attitudes toward all team partici- pation, which may affect their perfor- mance in teams in later employment. Many negative experiences can be attributed to lack of development in team processes. Business organiza- tions train teams extensively for suc- cessful functioning. Course teams can function successfully with a little classroom time spent on development

and training.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

In this article, I present aclassroom-tested Faculty Guide and Student Guide based on classroom experiences, consulting experiences with organizational teams, and the lit- erature. Students have reported their best course team experiences through use of these guides.

1. The teams did not work well

together; that is, they were a collection of individuals, each with his or her own agenda, rather than having a unified team objective.

2. The team members often were not

clear about the expectations for the team, regarding both the specific out- comes expected by the faculty and the level of team performance expected by each of the team members. For exam- ple, some team members were willing to settle for a C , whereas others were aiming for nothing less than an A, indi-

cating a lack of clear objectives for team performance.

3. Some team members became “free

riders” (sometimes called “social loafers”) and the remainder of the team members may have felt that (a) they had to take up the slack, (b) there was noth- ing that could be done about the prob- lem, (c) they lacked knowledge on what could be done, or (d) they lacked the skills to do whatever could be done about the free riders.

4. Group members did not know how

to build

a

team and maintain team effort.zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 . Team members did not know how to handle conflict within the team.

6 . Teams did not know (a) how to choose a team leader, (b) how to choose the best team leader(s) for a specific task, (c) what to expect from a team leader, or (d) how to recognize or reward team leader performance.

7.

Teams rarely made definite work assignments for each team member, nor did they establish specific due dates for each assignment (completion time for the activity). Decisions may have been made during team interaction (meet- ings), but the responsibility for the com- pletion or implementation of the deci- sion was not assigned to any particular individual. There was no direct assign- ment made for the activity or imple- mentation of the decision, nor was there any penalty assigned for not completing the activity or meeting by the estab- lished due date.8.

Most classroom teams had norecourse against noncontributing or dys- functional members.

9. Totally inclusive meeting times were difficult to establish, particularly if there were commuting (e.g., distance- learning), nontraditional, or working members in the team.

10. Full-time students may have had

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

4

or

5

simultaneous team projects (along with their class schedules) during a semester, which further complicated establishment of acceptable meeting times and greatly expanded out-of-class workloads, particularly for the good, conscientious team members who often ended up doing most of the work.Additionally, it has been observed that the values of generation

X

tend to be anti-team! As a group, the Xers are highly individualistic, visually oriented, and aligned with information technolo- gy, not with the sharing of information. Such factors, coupled with the fact that most classlcourse teams have had little or no training in team functioning, led to bad experiences with teams.Such bad experiences may produce negative student attitudes to future use of teams, possibly harming those stu- dents’ careers when they must handle team situations on the job and

in

the real world. What is taught poorly in college may contribute later to poor perfor- mance on the job.Interaction Communication Common interests Size

All leading to consensus

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Improving In-Class Team

Performance and Participant

Experiences

With a little in-class training about team functioning and some preliminary student

team

activities, the students’ neg- ative reactions to teams can be reduced or possibly even eliminated. The approach proposed in this article has been used in several classes with signifi- cant positive results. The vast majority of students using the techniques and work- sheets have enjoyed the team experience. Some of those students have commented that the approach provided their most rewarding team experience; for some, it produced their first positive one.Organizations that use teams success- fully spend long hours and millions of dollars training individuals to work in teams, training team leaders, and train- ing managers to manage teams.

(Motorola spends $30 million a year in

training, mostly on teams, and it has taken the company

10

years to develop teams to its satisfaction.) Following this model,I

concluded that some guidance for faculty and students would si@i- candy enhance team performance and the reactions that students have to teams. To assist faculty to prepare and train students to work in teams for course/class projects,I

prepared the attached, annotated Faculty Guide and Student Guide. The guides were origi- nally prepared for colleagues to use in their classes. Those colleagues suggest- ed that the guides be shared with other faculty, both within the university and more broadly. The Faculty Guide assists faculty members in preparing students for working in teams, and the Student Guide helps students to perform better in and have positive experiences with teams. The Faculty Guide has more nar- rative, briefly explaining the theory and reasoning behind the recommendations.The guides may seem overformalized and complex, but there is a reason for the formalization. Teams are formal mani- festations of groups, and effective groups require extensive development time, often years. To provide the climate for course/classroom teams to be successful would thus require extensive develop- ment time also, but course/classroom teams do not have such extended time periods to develop. Time constraints (semester lengths) and normally accept- ed standards necessitate that classroom teams develop and mature through a “quantum” acceleration of the necessary processes. The best way to facilitate such rapid development is to formalize the processes of group evolution.

The proposed steps are closely relat- ed to the requirements for the develop- ment of successful teams in the work environment. Steps corresponding to group characteristics and team develop- ment experiences from in the world of work have been modified to fit the classroom.

The guides are intended for use with teams that will be working together for

an

extended duration, for example, for a partial term or a whole term project. They are not intended for groups whose sole purpose is to discuss a single topic in a single class and then be disbanded.Classroom teams that have used the guides for team presentations, team operations in extended game simula- tions, and similar activities have extolled their virtues, and students have stated that adherence to the proposed principles has improved team coopera- tion and performance as well as student

attitude to team participation.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

November/December 2000 99

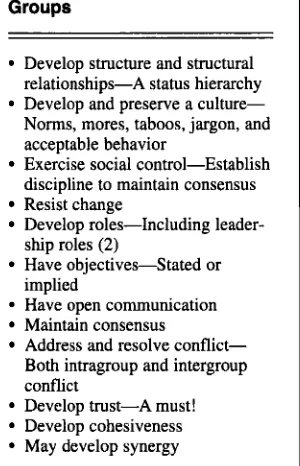

TABLE 2. Characteristics of Groups

Develop structure and structural relationships-A status hierarchy Develop and preserve a culture- Norms, mores, taboos, jargon, and acceptable behavior

Exercise social control-Establish discipline to maintain consensus Resist change

Develop roles-Including leader-

ship roles

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(2)Have objectives-Stated or implied

Have open communication Maintain consensus Address and resolve conflict- Both intragroup and intergroup conflict

Develop trust-A must! Develop cohesiveness May develop synergy

achieve (objective or benefit), (c) rules of behavior (mores or culture), (d) per- formance roles, and (e) generally tacit agreement on sanctions for noncompli- ance with group norms.

Size is a limiting factor. When the size of the group becomes too large for reaching a consensus on the common interests or the methods of attaining the common interest, the group either splin- ters or begins to formalize; that is, it begins to develop structured relation-

ships, formal objectives and rules, and

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

so

forth. Without the above conditions, groups never really come together cohe- sively-and formed teams will not come together either. Because it is not likely that those conditions will develop quickly enough in formed teams to facilitate cohesion, some artificial (for- malized) assistance is required.Some of the characteristics observ- able in established groups are identified in Table 2. Those characteristics are common to all groups and permit them to function cohesively. Because they

usually do not occur naturally or quick- ly enough in a formed team, the team must construct the characteristics con- sciously (see Table 2 ) .

In small groups, individuals either gather around a leader, or as the group defines its objectives, a leader emerges. The leader is the individual who the group feels will best enable it to achieve its objective(s). The originally chosen leader is often the most popular one.

A formed team must construct the objectives that lead to consensus. In a hastily formed classroom team, there is no beginning consensus, only a vague objective-to get the assignment done. Often there is no agreement on the level of work to be done, or the grade to be targeted. Therefore, there is no leader for the team to rally around.

Particularly in undergraduate classes, some team members may take the responsibilities of their roles lightly or engage in “social loafing.” Some team members may just want to complete the assignment at a minimum level, while others may strive for an A. Without a

previously stated agreement on an objective, those individuals striving for the A must assume a disproportionately large portion of the workload. They must

do

enough to earn the A for their own contribution while picking up the slack from the others.In “real world” work teams, the team members can exert some formal pres- sure on uncooperative team members. If the project earns an A, is it then equi-

table to give all members of the team an

A? Additionally, if an agreement has been developed regarding such behav- iors as shirking, the team members can deal with them during the project rather than after final project completion, when the team members are evaluated. They can direct the shirkers to do cer- tain activities. If they do not complete their assigned tasks, the team can impose some sort of sanctions against

uncooperative team members. This is the “exercise of social control” and the “development and preservation of

a

cul- ture” (see Table 2 ) . These activities per-mit the team to “maintain consensus.” Most professors have observed that different classes have different person- alities (or cultures).

So

too will teams have different cultures. These cultures need to be developed up-front.“Open communication” helps to encourage the trust that must develop among team members for effective functioning. Open communication, as well as the potential to discipline a dys- functional or disruptive team member, will permit the team to develop a trust- ing relationship with the professor. The team will believe that the professor is concerned with the welfare of the team members, and not simply working in his or her own comfort zone.

Unresolved conflict, particularly intra- group conflict, can significantly reduce a team’s effectiveness. The resolution of conflict, whether about goals, process, or final outcome, brings the team closer together, thus developing cohesiveness.

Classroom teams in which the “rules of the game” have been established up- front can function more successfully, like a well-trained team in the business world. Most important, the animosity toward team members and the antago- nism against other teams that often develop is greatly reduced. The pro- posed guidelines will not solve all of the problems, partly because some teams will not participate totally in the spirit of the guidelines but may just go through the motions. Teams that use the guide- lines will almost surely increase their performance and improve the members’ attitudes to team participation.

NOTE

The Faculty Guide and Student Guide are also posted on the Web site of the Center for Scholar- ship, Teaching, and Learning, Southeast Missouri State University, Cape Girardeau, MO.

100 Journal of Education for Business

APPENDIX A. Faculty Guide: Maklng Classroom Teams WorWsing Teams for Classroom Projects

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I. Establishing Teams

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Both ways have advantages and disadvantages.

A. Effective Teams

Teams can be established either by assigning individuals to a team or by permitting the students to self-select team members.

Group Functions-Members

trust and have confidence in each other; are attached and loyal;

help each other;

frankly share relevant and valuable information;

encourage everyone in the group to participate in the group task; and stress teamwork.

Clearly define team

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

goals and boundaries.Create a vision that’s supported by explicit tasks. Set clear short-term as well as long-term team goals. Encourage the development of team norms. Establish and maintain team traditions. Reinforce good attendance at team meetings. Measure and provide feedback.

Recognize and reward success.

Celebrate when the group achieves a goal. Ensure interpersonal communication. Support each other.

Be flexible.

Do what you say-Walk the talk.

Task Parameters

B. Team Membership

1. Assigning Team Members

The usual procedure for “real world” organizations.

The advantage of assigning team members is that the instructor can assure a mix of students on the team, either male and female, different majors, different ability levels or types, different ethnic backgrounds, international stu- dent representation, etc. Additionally, this approach will more likely replicate the way teams are formed in most “real world” situations.

The disadvantage of assigning members is that research indicates that other things being equal, member-selected

teams usually perform better.

The advantage of team self-selection is that self-selected teams usually perform better. Additionally, students can select individuals with whom they are familiar, with whom they feel they can work constructively and who have the same/similar schedules and commitments.

The disadvantage of self-selection is that the students may not obtain the team diversity that might otherwise be obtainable. Diversity usually adds to team problem solving and performance. Also, most teams in work organiza- tions are formed by management directive and, therefore, are not self-selected. However, once teams are formed, new members are often team selected.

2. Team Member Self-Selection

Team Membership should be as diverse as possible to improve alternative inputs and decision capabilities.

1. Clarifying Expectations (Faculty Expectations) C. Team Foundation

The faculty member should clearly specify what the team is expected to accomplish; i.e., the final outcome.

If the faculty member desires any parameters to be established, such as “at least five references from the Internet,” or “no references from the Internet,” then these parameters should be established “up front.”

2. Establishing Parameters (Faculty Imposed Parameters, if any) D. Team Formation

1. Team Leadership

A team leader can be appointed by the instructor. OR

The team may designate someone as the leader or chairperson. That individual should be given some authority as well as responsibility. This may best be handled as a team function. OR

Let the best leader surface-natural ascension.

The faculty member should be informed of the choice of leader.

Some teams might select a variety of leaders. For example, assume a team has been assigned to prepare a topic for presentation to the class. The team may select one leader to coordinate the research on the topic. It might select a second leader to organize the research into cogent parts, and a third leader to coordinate the classroom presentation. This sort of shared team leadership can be extremely productive.

A person should be identified as the individual responsible for keeping written records of the activities of the team (Goals/Objectives), meeting minutes, action assignments, progress, etc.

2. RecorderAteporterlScribe

The faculty member should also be informed of the choice of scribe.

(Appendix continues)

NovernbedDecember 2000 101

11.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Getting Organized A. Exchange of Information (Each Student)Phone numbers E-mail addresses Available meeting times

The faculty member should also be supplied with a copy of the names, phone numbers, and e-mail addresses of the team members, as well as the selected team leadedchairperson and scribe.

1. What is the team to accomplish?

B. Mission

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(Purpose)/Goals/ObjectivesAt what level?

What is to be the team outcome?

What is the extent of the outcome, e.g., a 30-page paper on a given topic, a series of completed problems, team deci- sions (maybe for a simulation game), or some other project?

Establish a project Completion Time, usually allowing time for integration, revision, or additions before the due date. 2. A Completion Time (Usually allowing time for revisions or additions)

C. Establish Team Purpose and Objective 1. Defining what must be accomplished. 2. At what level.

3. In what order.

The faculty member should be supplied with a copy of the Mission, Goals, and Objectives

In some cases, the faculty member may want to comment on the documentation or in other cases the faculty member may not wish to intrude upon the process of the team. Possibly the faculty member may not wish to request the team to submit the Objectives, especially if the team were to indicate the desired grade in the Objectives. If the grade desired were to be less than an “A” it may prejudice the faculty member in the evaluation of the final project.

1. Expected Behavior

2. Expectations of Members

D. Rules of Conduct

Notification of illness Major events

Interaction with the team

Missing meetings Late for meetings Unprepared for meetings Incomplete or late assignments

Inappropriate or counterproductive behavior No participation

Establishment of Consequences for improper action or inaction 3. Establishing Discipline

Establishing Discipline

All the above Rules of Conduct should be established “up front” so that each member knows what is expected of h i d h e r as well as the consequences of not meeting the expectations.

The faculty member may wish to be supplied with a copy of these, particularly in regard to the rules relating to participation, both physical and mental. This may forestall any later arguments as to the appropriateness of the expectations.

Faculty members may have a tendency to indicate that each team member will receive the same grade. This is unrealis- tic, but it is how many business teams are rewarded. However, unless team members have a means to “discipline” members there may be a tendency for individuals to engage in “social loafing,” a phenomenon in which a single indi- vidual makes little or no contribution to the team, sometimes not even participating. In business teams this is usually dealt with by team members. Some teams may expel a member. One organization’s teams impose a fine on members, 20% of the team’s weekly bonus, if the member is late or absent. The bottom line is that in classroom teams, unless the team or the instructor can in some way “discipline” members, that is, create consequences for nonparticipation, an individual or two may not fully participate. They may become “social loafers.” This unduly burdens the remainder of the team members and permits the nonparticipating member a free ride.

For Example: Progressive Discipline. Instruct teams to:

(a) have a heart-to-heart talk with the “slacker” and attempt to internally resolve the issue(s). (b) establish a written “code of behavior” or “conditions of continued involvement.”

(c) If the heart-to-heart talk and the written conditions do not resolve the issue(s), the instructor should talk to the accused “slacker” and address the problem(s).

(d) It may be advisable to do “peer evaluations” both midway through the term and at the end of the term. This input, if it indicates a problem, can be discussed with the group.

The main onus is on the group to resolve the issue(s). There is frequent conflict in real-world teams, and students should attempt to constructively resolve conflict within their groups.

If behavior becomes too “disruptive” because of extreme personality conflicts, it may be possible (or even necessary) for the faculty member to split up teams, e.g., create another team.

How are the students going to accomplish their objective? Who is to do what by when?

E. Develop a Strategy to Achieve the Desired Outcome

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(Appendix continues)

102

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Journal of Education for Businessr

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I

F. Faculty Assistance to Groups

It is important to allocate class time (especially early in the term or in the early part of the team development) to

establish the basic team processes, such

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

as developing Rules of Conduct and Establishing Discipline. Additionally, thefaculty member can observe the students addressing their assigned cases, simulations, exercises, etc. The faculty mem- ber can practice MBWA (Management By Walking Around) and observe the teams in action.

III. Working Processes A. Roles

1. Leader’s Role

C o n f i i n g meeting time and place Confirming frequency of meetings Establishing agenda for meetings Running meetings

C o n f i i n g task assignments and completion times to members Follow-up on assignments

Encouraging participants

Record objectives

Record assignments and due dates

Record brief “Minutes” of team meetings, establishing responsibilities Prepare and distribute handouts and other required materials

Integrate and report final document

Attend meetings

Be prepared to participate Participate and contribute

Do assigned work on time

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2. Scribe’s Role

3. Member’s Role

B. Decision MakinglProblem Solving 1. Decision Processes

Defining problem-clearly, concisely Exactly what do we need to do?

What process must we follow to accomplish our task? Gathering information

Coordinating information Discussing information

Evaluating suggestions

Selecting the approach to be used

Implementing the approach-Doing the work Completing the Project

Determine what is to be done

Make specific assignments-Who is to do what? Determine definite due dates and assignments Follow-up on assignments

Getting suggestions

2. Action Plans/Making Action Assignments

C. Group Processes

1. Obtaining ConsensusJCommitment

Consensus is selecting an approach that everyone can agree upon. It is not necessarily selecting an approach some- one or everyone thinks is the best. There are usually more than one acceptable solution or approach. Consensus can be expedited by holding open and honest communication. This means discussing the issues, nothing else.

In some cases consensus may lead to an inferior decision. However, the commitment fostered by obtaining consensus usually leads to a superior finished product because the commitment fosters cooperation and joint effort.

Step 1. Acknowledge that conflict exists Step 2. Identify the “real” conflict Step 3. Hear all points of view

Step 4. Together explore ways to resolve the conflict Step 5. Gain agreement on, and responsibility for, a solution Step 6. Schedule a follow-up session to review the resolution Approaches to Conflict Resolution

Avoiding-Ignoring the Conflict, not participating in the solution. Avoiding conflict completely may lead to fur- ther conflict. Uncooperative, unassertive.

Accommodating-Letting the other party win, trying to maintain apparent harmony. Attempting to satisfy the

other party’s concerns also may lead to later conflict. Cooperative, Unassertive.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Competing/Confronting/Forcing-A win-lose mentality. Struggle to win. May fall back on formal authority and rules to win. Uncooperative, Assertive.

2. Resolving conflict-Six Steps to Conflict Resolution

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(Appendix continues)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

NovembedDecember 2000 103

Compromising-’Ikying to partially satisfy everyone’s needs. A solution-oriented approach. Negotiation is usually involved where parties give and take. Partly Cooperative, Unassertive.

Collaborating-Working through issues, problem solving. The best solution-oriented approach. Cooperative, Assertive.

Obtaining Resolution (Four Principles for Obtaining Agreement)

Separate the people from the problem. (No name calling or accusations.) Focus on the issues.

Focus on interests, not positions. (What is each party trying to accomplish?) Generate other possibilities, make the pie bigger.

Insist that results be based on some objective standard. 3. Using Discipline

Discipline must be fairly and consistently administered. It must be a team effort. Ignoring problems requiring disci- pline can be and almost always is disruptive to the team effectiveness,.

Dividing the work

Making specific assignments

Setting levels of expected performance

Setting due dates

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

4. Team Action Planning

Follow-up

5. Contributing to Effectiveness Cohesiveness

Commitment Trust-Two Facets

1. Trust in the instructor

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2. Trust in the team members

Trust that the individual will do the assignment Trust that the individual can do the assignment

Open Honest Consistent Forthcoming

Do the work you commit to do Do the work thoroughly

Do quality work-The team should not accept less! Being Trustworthy

Confronting conflict and conflict resolution Maintaining discipline

Using consensus

Some team evaluation forms are attached for your information or possible use.

APPENDIX

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

B.

Student Guide: Making Classroom Teams WorkI. Establishing Teams A. Effective Teams

Team Functions-Team members

trust and have confidence in each other; are attached and loyal;

help each other;

frankIy share relevant and valuable information;

encourage everyone in the group to participate in the group task; and stress teamwork.

Clearly define team

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

goals and boundaries.Create a vision that’s supported by explicit tasks. Set clear short-term as well as long-term goals. Encourage the development of team norms. Establish and maintain team traditions. Reinforce good attendance at team meetings. Measure and provide feedback.

Recognize and reward success.

Celebrate when the team achieves a goal. Ensure interpersonal communication. Support each other.

Task Parameters

(Appendix continues)

104 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for BusinessAre flexible.

Do what they say-Walk the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

talk.1. Assigned Membership-Most Realistic

2. Team Selected Membership

B.

Team MembershipThe usual procedure for “real world” organizations.

Advantage-Often the most productive teams

Disadvantage-Can be too homogeneous-Too many “A” or “C” students.

(Birds of a feather flock together!)

Too many students from a single major, etc. Can Lack Diversity-Individuals often select “like” individuals.

Team membership should be as diverse as possible to gain different perspectives.

1. Clarify Expectations (Faculty’s Expectations)

2. Clarify Parameters (Faculty Imposed Parameters, if any) C. Team Foundation

The faculty member should clearly specify what the team

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

is expected to accomplish; the final outcome.For example, if the faculty member wants at least five references from the Internet, or none from the Internet, or at

least

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

4 references from the last 3 years, etc., these parameters should be stated “up front.”D. Team Formation 1. Team Leader

Assigned/Appointed Elected (by team members) Naturally selected

At times a team might find it advantageous to utilize more than one leader. For example, assume that the team has been given the assignment to research a topic and present the topic to the class. The team might want to select one individual to coordinate the research on the topic, another individual to coordinate the organization of the research into cogent units, and a third individual to coordinate the actual presentation.

Such shared team leadership can be extremely successful. 2. Team Reporter/Scribe

Keeping written records of the activities of the team, e.g., Goals/Objectives, Action assignments, brief team meeting minutes, progress, etc.,

Inform the Instructor of the selected team leader(s) and reportedscribe.

II.

Getting OrganizedA. Exchange of Information Phone Numbers E-Mail Addresses Available Meeting Times

The faculty member should be supplied with a copy of the team members’ names, phone numbers, and e-mail address- es as well as the selected team leader and reporter.

1. What do you want to accomplish?

B.

Mission (Purpose)/Goals/ObjectivesAt what level?

What is to be the team activity and outcome?

What is the extent of the outcome, e.g., a 30-page paper on a given topic, a series of completed problems, team deci- sions (maybe for a simulation game), or some other project?

2. Establish a Project Completion Time (usually allowing time for integration, revision and additions.) The faculty member should be supplied with a copy of the Mission/Goals/Objectives.

In some cases the faculty member may want to comment on the documentation and ask for clarification, or additions to the documentation, or may request inclusion in establishing the team’s Mission, Objectives, Priorities, etc.

C. Establish Team Purpose and Objective 1. Defining what must be accomplished

2. At what level

3. In what order

Expected Behavior Expectations of Members D. Rules of Conduct

Notification of illness Major events

Interaction with the team Establishing Discipline

Missing Meetings Late for Meetings Unprepared for Meetings Incomplete or Late Assignments

Inappropriate or Counterproductive Behavior No Participation

Establish consequences for improper actions or inaction.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(Appendix continues)

NovembedDecember 2000 105

I

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

These issues must be resolved by the team members, possibly with faculty facilitation if problems arise.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Establishing Discipline

All of the above Rules of Conduct should be established “up front” so that each member knows what is expected of

h i d e r as

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

well as the consequences of not meeting the expectations. For Example: Progressive Discipline1.Have a heart-to-heart talk with the “slacker” and attempt to internally resolve the issue(s). 2.Establish a written “code of behavior” or “conditions of continued involvement.”

3.If the heart-to heart talk and the written conditions do not resolve the issue(s), the instructor should talk to the accused “slacker” and address the issues raised by the team.

4.It may be advisable to do “peer evaluations” both midway through the term and at the end of the term. This input, if it indi- cates a problem, can be discussed with the group.

The main onus is on the group to resolve the issue(s). There is frequent conflict in “real world” teams and the students should attempt to constructively resolve conflict within their groups.

How are you going to reach your objectives? Develop a plan of action and sequencing of activities.

E. Develop a Strategy to Achieve the Desired Outcome

F. Some class time should be allocated early in the process to permit the teams to get organized and establish meeting times

In. Working Processes A. Roles

1. Leader’s Role

Confirming meeting time and place Confirming frequency of meetings Establishing agenda for meetings Running meetings

Confuming task assignments and completion times to group members Follow-up on assignments

Encouraging participants

Record objectives.

Record assignments and due dates. Record brief “minutes” of team meetings.

Prepare and distribute handouts and materials required. Integrate and report final document.

Attend meetings.

Be prepared to participate. Participate and contribute. Do assigned work on time. 2. Scribe’s Role

3. Members’ Roles

B. Decision ProcesdProblem Solving 1. Decision Making

Defining problem-clearly, concisely Exactly what do we need to do?

Gathering information Discussing information Coordinate information Elicit suggestions Evaluate suggestions Select the approach

Implement the approach-Doing the work Complete the project

Determine what is to be done

Make specific assignments-Who is to do what? Determine definite due dates (By when)

Follow-up on assignments

What process must we follow to accomplish the task?

2. Action PlansJMaking Action Assignments C. Group Processes

1. Obtaining Consensus (Commitment)

Consensus is selecting an approach that everyone can agree upon. It is not necessarily selecting an approach some- one or everyone thinks is the best. There are usually more than one acceptable approach or solution to solve most problems. Consensus can be expedited by holding open and honest communication. This means discussing the issues, nothing else.

Obtaining consensus facilitates obtaining commitment and thus the participation of the team members.

Six Steps to Conflict Resolution Step 1. Acknowledge that conflict exists Step 2. Identify the “real”

2. Resolving Conflict

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(Appendix continues)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

106 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for BusinessI

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Step 3. Hear all points of viewStep 4.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Together explore ways to resolve the conflictStep 5. Gain agreement on, and responsibility for, a solution

Step 6.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Schedule a follow-up session to review the resolutionApproaches to Conflict Resolution

Avoiding-Avoiding conflict completely usually leads to further conflict. Ignoring the Conflict, not participating in the solution. Uncooperative, Unassertive.

Accommodating-Attempting to satisfy the other party’s concerns, which also leads to later conflict. Letting the other party

win, trying to maintain apparent harmony. Cooperative, Unassertive.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Competing/Confronting/Forcing-Struggle to win. May fall back on formal authority and rules to win. A win-lose mentali- ty, Uncooperative, Assertive.

Compromising-A solution-oriented approach. Negotiation is usually involved where parities give and take. Dying to par- tially satisfy everyone’s needs. Partly Cooperative, Unassertive.

Collaborating-The best solution-oriented approach. Working through issues, problem solving. Cooperative, Assertive. Obtaining Resolution (Principles for Obtaining Agreement)

Separate the people from the problem (No name calling or accusations). Focus on the issues, not personalities.

Focus on interests, not positions.

Generate other possibilities, make the pie bigger. Insist that results be based on some objective standard.

Discipline must be fairly and consistently administered. It must be a team effort.

Ignoring problems requiring discipline can be and almost always is disruptive to the team effectiveness. Problems that are ignored do not go away; they usually fester and become worse.

Rules should be agreed upon

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

“up front,” before they become necessary. If they are not agreed upon up front theycan be viewed as being directed toward a particular individual. When this happens it is usually perceived as being “unfair.”

Divide the work

Make specific assignments to specific individuals Set levels of expected performance

Set due dates for completed work

What is each side trying to obtain, not what they want done to obtain it.

3. Using Discipline

4. Action Planning

Follow-up D. Contributions to Effectiveness

Cohesiveness Commitment Trust--Two Facets

1. Trust the instructor

2. Trust the group members

Trust that the individual will do the assignment Trust that the individual can do the assignment

Open Honest Consistent Forthcoming

Do the work you commit to do Do the work thoroughly

Do quality work-The team should not accept less! Being ’hstworthy

Confronting conflict and conflict resolution Maintaining discipline

Utilizing Consensus

James A. Buckenmyer DBA Supported by:

Stanley Stough

PhD

Diane Pettypool DBA Professors of ManagementSoutheast Missouri State University

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Note. Guides are acccessible through the Center for Scholarship, Teaching and Learning (CSTL) Web site,

Southeast Missouri State University.

NovemberDecember

2000

107