Books of related interest

EARL OF ROCHESTER

THE POEMS

AND

LUCINA’S RAPE

EDITED BY

KEITH WALKER and NICHOLAS FISHER

Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell.

Registered Office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

Editorial Offices

350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at

www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell.

The right of Keith Walker and Nicholas Fisher to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rochester, John Wilmot, Earl of, 1647–1680.

John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester : the poems, and Lucina’s rape / edited by Keith Walker and Nicholas Fisher.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4051-8779-4 (alk. paper)

I. Walker, Keith, 1936–2004 II. Fisher, Nicholas III. Title.

PR3669.R2A6 2010 821'.4–dc22

2009032171

Hbk: 9781405187794

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Set in 11/13.5pt Dante by Graphicraft Limited, Hong Kong Printed in Malaysia

KEITH WALKER & HAROLD LOVE

Contents

List of Illustrations viii

Note on This Edition ix

Acknowledgments x

Chronology xii

Introduction xvii

Further Reading xxviii

Abbreviations xxxii

POEMS

Juvenilia 1

Love Poems 5

Translations 56

Prologues and Epilogues 61

Satires and Lampoons 68

Poems to Mulgrave and Scroope 111

Epigrams, Impromptus, Jeux d’esprit, etc. 131

Poems Less Securely Attributed to Rochester 138

LUCINA’S RAPE OR THE TRAGEDY OF VALLENTINIAN 161

Index of Proper Names 253

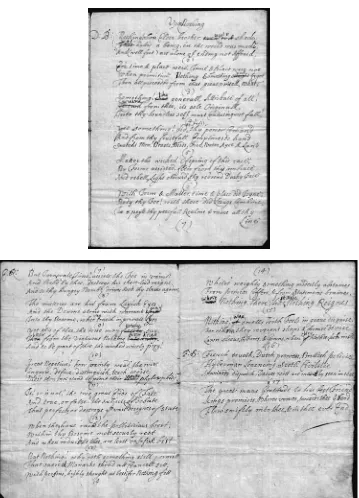

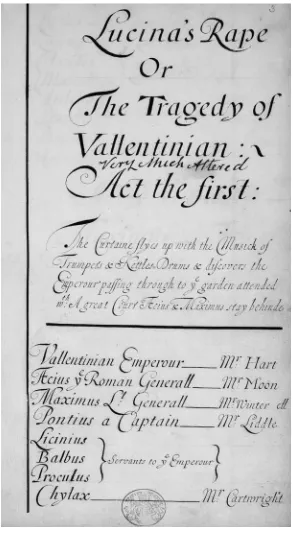

List of Illustrations

1. Engraved portrait of Rochester, 1681 (collection of Howard Erskine-Hill) vi 2. Title-page of Poems on Several Occasions By the Right Honourable,

The E. of R— (Antwerp [ London], 1680) ( Pepys Library, Magdalene

College, Cambridge) xxxiv

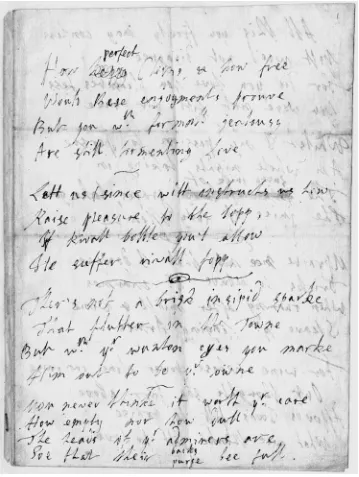

3. ‘How perfect Cloris, and how free’, Nottingham University MS

Portland Pw V 31 22

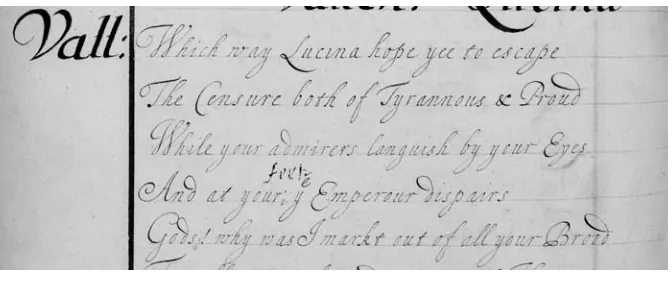

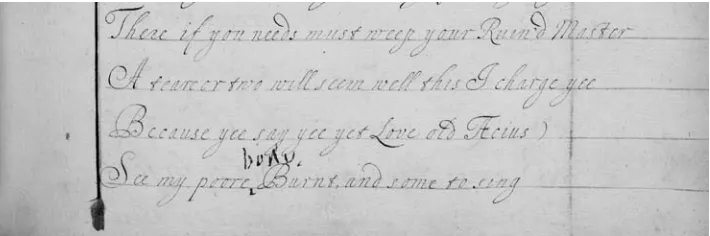

4. Title-page A Satyr against Mankind [ London, 1679] ( private collection) 89 5. Upon Nothing, National Archives, Kew, Box C 104/110 Part 1 105 6. Lucina’s Rape Or The Tragedy of Vallentinian, British Library Add.

MS 28692 (title-page) 161

7. Lucina’s Rape Or The Tragedy of Vallentinian, British Library Add.

MS 28692 (correction to I.i.166) 173

8. Lucina’s Rape Or The Tragedy of Vallentinian, British Library Add.

Note on This Edition

Acknowledgments

My chief debts are, firstly, to Ken Robinson, who introduced me to the Earl of Rochester while I was an undergraduate at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, and then supervised my master’s dissertation on satiric and verse epistles in the Restoration Period; and, secondly, to Paul Hammond at the University of Leeds who was the supervisor of my doctoral dissertation on the early publishing history of Rochester’s work, and has generously continued to allow me to draw on his detailed knowledge of Restoration literature. I cannot adequately express my debt to them both, and particularly to Paul Hammond, for their stimulation, patience and advice over a lengthy period. I am also most grateful for the individual kindnesses and encouragement I have received from Philip Aherne, Peter Beal, John Carey, Larry Carver, Warren Chernaik, Robert Hume, David Gareth Jones, Thomas MacFaul, Brian Oatley, James Grantham Turner and Henry Woudhuysen. Philippa Martin, Curator of the Government Art Collection, provided invaluable advice and help, and Howard Erskine-Hill generously allowed me to include an illustration of Rochester from his extensive collection of prints from the long eighteenth century. This edition has also profited greatly from the enthusiasm and expertise of the publishing team at Blackwell – Emma Bennett, Caroline Clamp, Isobel Bainton and Sarah Pearsall – and I must also record the tolerance of my wife Pam, and children Francis, Rachel and Harriet, which has been nothing short of heroic.

permission of Magdalene College, University of Cambridge. To the librarians and staff of all these institutions I express my warmest thanks for their assistance.

The work for this edition was undertaken while I was a Visiting Research Fellow at the Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, and I thank Warwick Gould for his generosity in extending my fellowship to allow me to undertake the necessary study. Latterly a Visiting Research Fellowship at Merton College, Oxford, allowed the project to be completed and I am most grateful to the Warden, Chaplain and Fellows for the generosity of their welcome and hospitality.

My obligation to Keith Walker will be apparent on almost every page (and coincidentally he supplied me with his transcript of the Harbin MS when I was completing my doctorate). But as Keith did a quarter of a century ago, so I end by acknowledging my debt to Harold Love. It was he who suggested that I should under-take this revision, and he then took an active interest in my progress; one of his last communications was to bring his discovery of another text of ‘My dear Mistress’ to my attention. This volume is dedicated to the memory of these two outstanding Rochester scholars.

Chronology

Historic and Literary Events

30 January: execution of Charles I; future Charles II in exile at The Hague 19 May: England declared a

Commonwealth or Free State 2 August: Charles II invades England 3 September: royalist army defeated at Battle of Worcester and Charles escapes to France with Lord Wilmot

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan

Christopher Bowman opens first coffee-house in London in St Michael’s Alley, Cornhill

10 July: start of First Dutch War (1652–54)

16 December: Cromwell becomes Lord Protector

3 September: Cromwell dies; son Richard succeeds as Lord Protector 25 May: Richard Cromwell resigns, Rump Parliament re-establishes Commonwealth

13 October: army-controlled Committee of Safety replaces Rump Parliament 26 December: Rump Parliament re-instated

1 April: born at Ditchley House, Oxfordshire, son of Henry, Lord Wilmot and Anne, widow of Sir Henry Lee

13 December: father created Earl of Rochester

Rochester in Paris with mother

Still in Paris

Rochester’s Life

18 January: matriculates at Wadham College, Oxford

c. May: ‘Vertues triumphant Shrine’ c. December: ‘Impia blasphemi’

c. January: ‘Respite great Queen’ February: awarded pension of £500 p.a. 9 September: receives degree of MA from Chancellor, Earl of Clarendon 21 November: embarks on Grand Tour with Sir Andrew Balfour

1 October: in Venice

26 October: signs Visitors’ Book at University of Padua

Visits Charles II’s sister Henrietta, Duchess of Orleans

25 December: delivers letter from Henrietta to Charles II at Whitehall

26 May: attempts to abduct heiress Elizabeth Malet; imprisoned in Tower 19 June: freed from Tower

6 July: joins Fleet

2 August: under fire in Bergen harbour 9 September: still with Fleet

16 September: back at Court 31 October: gift of £750 from King

1660

2 January: Monck’s forces enter England

3 February: Monck enters London 4 April: Charles’s Declaration of Breda issued

8 May: Charles proclaimed King in London

29 May: Charles enters London 21 August: patents granted for re-opening of theatres

20 December: Corporation Act

19 May: Act of Uniformity with revised

Book of Common Prayer attached receives royal assent

10 June: Licensing Act takes effect 21 May: Charles II marries Catholic Catherine of Braganza

Butler, Hudibras Part I

7 May: Theatre Royal, Drury Lane opens

Butler, Hudibras Part II

4 March: Second Dutch War (1665–67) begins

3 June: Dutch fleet defeated at Battle of Lowestoft

5 June: theatres in London closed by Plague

Rochester’s Life

21 March: appointed Gentleman of the Bedchamber to Charles II with pension of £1,000 p.a. and lodgings in Whitehall June: commissioned in Prince Rupert’s Troop of Horse

June–July: naval service under Sir Edward Spragge, displaying conspicuous bravery

29 January: marries Elizabeth Malet 14 March: assumes post of Gentleman of the Bedchamber

29 July: summoned to Parliament by royal writ

2 October: pension of £1,000 authorised 10 October: takes seat in House of Lords 28 February: appointed Gamekeeper for Oxfordshire

16 February: strikes Thomas Killigrew in King’s presence; pardoned

12 March: sent to Paris by Charles II with letter for his sister

19 April: robbed of valuables in Paris 21 June: set upon at the Paris opera July: returns to England

30 April: daughter Anne baptised at Adderbury

22 November: forced by illness to decline duel with Mulgrave

2 January: son Charles baptised

Autumn: ‘All things submit themselves’, ‘Cælia, that faithful Servant’

Historic and Literary Events

25 July: Dutch defeated in Battle of North Foreland

2–5 September: Great Fire of London

16 November: first issue of London

Gazette

Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux, Satires

13 June: Dutch destroy English fleet on

Medway, capture flagship Royal Charles

29 November: Chancellor Hyde flees to France; replaced by ‘Cabal’ ministry under Arlington

Dryden, Annus Mirabilis

Milton, Paradise Lost

Dryden appointed Poet Laureate

Dryden, An Essay of Dramatick Poesie

21 August: Death of Queen Mother, Henrietta Maria

22 May: Charles signs secret Treaty of Dover

October: Arrival of Louise de Kerouaille (future mistress to King; created Duchess of Portsmouth) Dryden, Conquest of Granada, Pt. 1

Thomas D’Urfey, Wit and Mirth

9 November: Dorset Garden Theatre opens

Milton, Paradise Regain’d andSamson Agonistes

Dryden, Conquest of Granada, Pt. II

Buckingham, The Rehearsal

Wycherley, Love in a Wood

Rochester’s Life

21 March: duel with Viscount Dunbar prevented

Spring: dedicatee of Dryden’s

Marriage-a-la-Mode

‘The Gods, by right of Nature’ ‘Wit has of late’

‘In the Isle of Brittain’

January: leaves Court after delivering ‘In the Isle of Brittain’ in error to King 27 February: appointed Ranger of Woodstock Park

‘What Timon, does old Age, begin’ 2 May: appointed Keeper of Woodstock Park

‘Strephon, there sighs not’

Satire against Man

13 July: daughter Elizabeth baptised 4 January: Charles approves building of small building at Whitehall Palace for Rochester

24 January: appointed Master, Surveyor and Keeper of King’s hawks

Late Spring: dedicatee of Lee’s Nero

May: occupies High Lodge, Woodstock 25 June: smashes King’s chronometer in Privy Garden

‘Well Sir ’tis granted’

6 January: daughter Malet baptised February: ill, reported dead

March: Satire against Man circulating 17 June: brawl with Watch at Epsom resulting in death of Billy Downs Summer: Alexander Bendo disguise

25 January: Theatre Royal burns down

15 March: Charles issues Declaration of Indulgence

17 March: Third Dutch War begins (1672–74)

28 May: indecisive naval battle off Southwold

29 March: imposition of the Test Act 20 September: Duke of York marries by proxy Catholic Mary of Modena Autumn: a ‘country party’, opposed to anti-Tolerationist policies of King’s chief minister, Danby, starts during parliamentary session to form around Halifax and Shaftesbury; Buckingham joins early 1674, and within a decade group formalised as ‘Whig’ party 9 February: peace concluded with Dutch

26 March: opening of new Drury Lane Theatre

September: collapse of ‘Cabal’ ministry

Spring: Crowne’s Calisto produced at Court

17 August: Charles signs agreement with Louis XIV to dissolve Parliament if supplies not provided

16 February: Charles concludes second secret treaty with Louis XIV, receiving £100,000 p.a.

Etherege, The Man of Mode

Wycherley, The Plain Dealer

Rochester’s Life

Spring: begins liaison with Elizabeth Barry 13 April: petitions King for estates in Ireland

‘Some few from Wit’

4 June: Cook stabbed at tavern in Mall where Rochester dining

August: entertains Buckingham in lodgings at Whitehall

October: receives visit from Buckingham at Woodstock

November: elected Alderman at Taunton, Somerset

December: daughter Elizabeth Clerke born to Elizabeth Barry

Early in year: very ill

Upon Nothing

‘Dear Friend. I hear this Town’

October: begins weekly conversations in London with Burnet (until April)

March: accepts challenge from Edward Seymour, but duel averted

End April: leaves London for last time; travels to Somerset; health collapses End May: brought by coach to Woodstock June: repents his life, and is reconciled with Church of England; visited by many clergymen

20 –24 July: visited by Burnet

26 July: dies at High Lodge, Woodstock Autumn: unauthorised publication of

Poems on Several Occasions

November: publication of Burnet’s Some

Passages of the Life and Death of . . . Rochester

Historic and Literary Events

Dryden, All for Love

February: Shaftesbury, Buckingham and others imprisoned by House of Lords

4 November: William of Orange marries Princess Mary

Butler, Hudibras Part III

17 May: secret treaty between Charles and Louis XIV promising neutrality in return for subsidy

13 August: first allegations of Popish Plot

20 November: Additional Test Act passed 26 May: Parliament prorogued and dissolved (12 July) to prevent passage of Exclusion Bill (reconvenes 21 October 1680)

Summer: Jane Roberts, former mistress of King, dies, attended by Gilbert Burnet May/June: Parliament fails to renew Licensing Act

4 December: death of Thomas Hobbes Burnet, History of the Reformation of the Church of England, vol. 1

April: Penny post system established in London by William Dockwra

1677

1678

1679

Introduction

The Man

John Wilmot, second Earl of Rochester, was born on All Fools’ Day, 1647, at Ditchley in Oxfordshire on the estate that had belonged to his mother’s first hus-band, Sir Henry Lee. Rochester’s father, Lord Wilmot, was a royalist general; witty, restless and hard-drinking, he was with the exiled court in Paris, and hardly saw his son. In consequence Rochester was brought up by his mother, who was tough-minded and a not uncommon example of well-born female piety. Although his exposure to the Bible and Prayer Book would continue through the daily routine of biblical study and prayers at his school, it was probably she who so impressed those texts on his memory that he would remember their cadences on his deathbed.

Rochester spent part of his childhood in Paris, but most of it in Oxfordshire. He was tutored by his mother’s chaplain, attended Burford Grammar School, and went up to Wadham College at the age of 12. He was at Oxford when King Charles came back to England, and he grew debauched there with the active encouragement of Robert Whitehall, a fellow of Merton college. (His more formal education would in any case have ended when he left Burford Grammar School: post-Restoration Oxford was not a place where young gentlemen were expected to study.) He took his degree of Master of Arts in 1661, and for the next three years he travelled in France and Italy with a Scottish physician as his tutor. He arrived back at the court which was to be the cen-tre of his life on Christmas Day 1664, with a letter for Charles from his sister in Paris. Described by his biographer Gilbert Burnet as ‘tall and well made, if not a little too slender’,1Rochester quickly gained a reputation for easy grace and wit. He was

the youngest member of his set apart from Sir Carr Scroope and John Sheffield, Earl of Mulgrave. He was later to quarrel with both men, facts recorded substantially in his poetry.

What is known of Rochester’s life as a courtier is mostly in this early period, before myth takes over the record. A suitor for an heiress, Elizabeth Malet, Rochester kid-napped her prematurely, and was punished by Charles with imprisonment in the Tower, from which he was soon freed, to make good his disgrace by fighting bravely in a sea battle against the Dutch (and subsequently marrying Elizabeth with the King’s blessing). His earliest extant letter is a full account of his experiences, which make the ironic reference to ‘Dutch prowess’ in Upon Nothing( l. 46) puzzling.2

Certain patterns of life can be discerned: recurrent bad behaviour, for which Rochester was first in disgrace, then quickly forgiven by the indulgent Charles; drunkenness, quarrels, duels, and (the details are more doubtful here) love affairs. He had four legitimate children and a bastard daughter by the actress Elizabeth Barry. When in disgrace, Rochester would disappear to France, or go into hiding and disguise. Gilbert Burnet records:

He took pleasure to disguise himself, as a Porter, or as a Beggar; sometimes to fol-low some mean Amours, which, for the variety of them, he affected; At other times, meerly for diversion, he would go about in odd shapes, in which he acted his part so naturally, that even those who were on the secret, and saw him in these shapes, could perceive nothing by which he might be discovered. (Some Passages, pp. 27–8)

The ability to assume another’s role is a striking feature of Rochester’s poetry, as of his life.3

Rochester was deeply involved with the Restoration stage, and this involvement is probably the most fully documented series of facts about his life. He seems to have acted as patron to most of the playwrights – Dryden, Shadwell, Crowne, Lee, Otway, Settle and Fane – and the majority of these have left us testimonies of their relations with him, unfortunately usually only in the form of a dedication. Rochester’s only full-length play, Lucina’s Rape Or The Tragedy of Vallentinian, adapted and improved Fletcher’s The Tragedie of Valentinian, but he also contributed a scene to a play by Robert Howard, began a prose comedy, and contributed the prologue or epilogue to four plays.4 Theatrical motives and imagery dominate much of his

verse.

In the later 1670s there is evidence of greater seriousness and greater involvement in affairs of state. During the middle of the decade, four events of importance are 2 It might, however, be a topical reference to the defeat of William of Orange by the French at Mont Cassell on 11 April 1677, and the subsequent Dutch focus on seeking peace, which was not achieved until the Treaty of Nijmegen was signed with the French on 10 August 1678.

3 Role-playing and disguise in Rochester is the theme of Anne Righter’s British Academy lecture (Proceedings of the British Academy, 53, 1967, 1968).

recorded: Rochester’s accidental handing of his satire ‘In the Isle of Brittain’ to the King during the festivities at Court at Christmas 1673; his destruction of the sundial in the Privy Garden at Whitehall on 25 June 1675; his part in the affray at Epsom on 17 June 1676 that led to the death of a Mr Downs (see the description given in the notes to ‘To the Post Boy’); and later that summer his setting up in disguise as the medical practitioner ‘Alexander Bendo’ on Tower Hill, London. Between February and May, 1677, he regularly attended the House of Lords, and in the pre-face to the printed edition of Rochester’s play (Valentinian(London, 1685)), Robert Wolseley confirms his interest in politics during his last years. His self-styled ‘death bed repentance’5followed from a series of regular conversations he had between October

1679 and April 1680 with a former chaplain to the King, Gilbert Burnet, and is recorded in Some Passages. This conversion, whether real or fantasy, figured largely in his reputation but has little to do with the quality of his poetry. Rochester died on 26 July 1680.

* * *

One Man reads Milton, forty Rochester,

This lost his Taste, they say, when h’lost his Sight; Miltonhas Thought, but Rochesterhad Wit. The Case is plain, the Temper of the Time, One wrote the Lewd, and t’other the Sublime.

(‘Reformation of Manners’, Poems on Affairs of State (London, 1703), p. 371) Who read Rochester? In his An Allusion to HoraceRochester himself suggested a fit audience:

’tis enough for me

If Sydley, Shadwell, Shepheard, Wicherley,

Godolphin, Butler, Buckhurst, Buckinghame 5 And some few more, whome I omitt to name 6 Approve my sence, I count their Censure Fame. 7

the right veine’; in Mr Smirke; or the divine in mode(1676), Marvell quotes from the as yet unpublished A Satyre against Reason and Mankind. Dryden, Aphra Behn, Thomas Otway, John Oldham, Edmund Waller, Samuel Pepys, and John Evelyn all read him.6The first record of close reading by a contemporary is the Court sermon

preached on 24 February 1675 against Rochester’s satire (among other things) by Edward Stillingfleet (1635–99), who clearly found the tenor of the poem subversive.

Stillingfleet, a future Dean of St Paul’s and Bishop of Worcester, was one of the King’s chaplains, so it is unsurprising that he should have seen the poem before it was printed. The poem attracted four verse replies: An Answer to the Satyr against Man, by the Oxford orientalist Edward Pococke (1648 –1727) appeared as a broad-side in July 1679; A Satyr, In Answer to the Satyr against Man, by a member of Rochester’s Oxford college, Thomas Lessey, was first published in the miscellany col-lection Poetical Recreationsin 1688; the anonymous Corinna, or, Humane Frailty. A Poem. With an Answer to the E. of R—-’s Satyr against Man in 1699; and the anonymous manuscript poem An answer to a Sat[?yr against R]eason & Mankind (Cambridge University Add. MS 42).7

Very soon after Rochester’s death a pirated edition of his poems appeared which quickly went into 11 or more editions. It was published ‘meerly for lucre sake’, as the antiquary Anthony à Wood put it, so presumably there were buyers. The com-plex proliferation of editions (there are four series of Rochester’s poems) continued throughout the eighteenth century.

Text

The complexity of the situation of Rochester’s texts is paralleled only by that of Donne’s, for in each case, only a few poems were published in the poet’s lifetime, and a single body of texts on which to base an edition is simply unavailable to an editor. The first printed edition of Donne, in 1633, was derived from non-authoritative manuscript copies, and his editor, as with Rochester, is faced with the task of hav-ing to evaluate many manuscript copies. Only nine poems by Rochester, some show-ing signs of revision, have survived in his own hand, and, so far as is known, he authorised the publication of just three works written when he was 13, together with, implicitly, the prologues or epilogues he contributed to four staged plays. The five

6 For a useful summary, see Rochester: The Critical Heritage, ed. David Farley-Hills (London, 1972), pp. 5–12. This compilation usefully charts Rochester’s reputation as a poet during his lifetime and up to the early part of the twentieth century. Current appreciation of Rochester as a writer of significant abil-ity is traceable to the publication of the ground-breaking editions of Pinto (1953) and Vieth (1968). 7 For transcriptions of the Cambridge MS, together with the fuller version of Lessey’s poem that appears

most important collections are in the two printed texts Poems on Several Occasions By the Right Honourable, the E. of R—([London], 1680) and Jacob Tonson’s Poems, &c. on Several Occasions: with Valentinian, A Tragedy (London, 1691), and in three manuscripts: Yale University MSS Osborn b 105 and b 334 (the latter known as the ‘Hartwell’ MS) and Thynne Papers, vol. XXVII at Longleat House, Wiltshire (the ‘Harbin’ MS).

1680 contains 61 poems, only 33 of which are now thought to be by Rochester. The collection is badly printed, bears no publisher’s name, and has the false imprint ‘Printed at ANTWERP’. Eleven closely similar but separate editions, spanning some 10 years, have been identified.8 1691 was published, and probably edited, by Jacob

Tonson, with a preface by Thomas Rymer; it contains 39 poems, 37 of which are now considered to be by Rochester, and attributes eight to him for the first time. For long, 1691was thought to be the best early edition of Rochester’s work, but whereas 1680has all the marks of an unauthorised edition, 1691 has all the deficiencies of an authorised one: it omits violently personal poems like On Poet Ninny, Epigram upon my Lord All-pride, On the supposed Author of a late Poem in defence of Satyr, A very Heroicall Epistle In answer to Ephelia; it also omits temperately personal poems like An Allusion to Horace(out of deference to Dryden, whose publisher Tonson was?), and obscene poems like ‘I Fuck no more than others doe’, On Mrs. W— llis, Mistress Knights Advice to the Dutchess of Cleavland, in Distress For A Prick, and A Ramble in Saint James’s Parke. It is an avowedly castrated text,9omitting stanzas from The Disabled Debauchee, ‘How

happy Chloris, were they free’, Love to a Woman, and ‘Fair Clorisin a Piggsty lay’. Worse, from the point of view of an editor who wishes to base a text on 1691, its versions of some 19 of the poems it has in common with 1680are derived wholly or in part from the earlier collection.

Yale MS Osborn b 105 is closely related to the ancestor of 1680, and is an antho-logy of Restoration poetry, with attributions that are in general reliable, and on the whole good texts for 30 of the poems. Unfortunately there are seven gaps of 45 leaves which have been cut away ( pp. 35–44, 63–6, 77–86, 115–32, 153–8, 161–84, 195–212). David M. Vieth has painstakingly investigated the probable contents of these miss-ing leaves,10and concludes that the whole or part of eight or possibly more poems

probably by Rochester are missing from the Osborn manuscript. Among these are,

8 See Rochester’sPoems on Several Occasions, ed. James Thorpe (Princeton, NJ, 1950), pp. xi–xxii; Nicholas Fisher and Ken Robinson, ‘The Postulated Mixed “1680” Edition of Rochester’s Poetry’, PBSA, 75 (1981), 313–15.

9 ‘For this matter the Publisherassures us, he has been diligent out of Measure, and has taken exceeding Care that every Block of Offence shou’d be removed.

So that this Book is a Collection of such Pieces only, as may be received in a vertuous Court, and not unbecome the Cabinet of the Severest Matron’. (1691, sig. A6v(italics reversed))

beyond doubt, such substantial poems as A Ramble in Saint James’s Park, and The Imperfect Enjoyment.

The Hartwell and Harbin MSS are two ‘vitally important’ documents that draw on a source that was available to Tonson for 1691, and (on the basis that none of the indecent poems are included) which was possibly prepared for, or even by, one or other female members of Rochester’s extended family, such as his niece Anne Wharton.11They contain, respectively, texts for 26 and 24 of the poems, and an

addi-tional significance of the Hartwell MS is that not only is it the only major manuscript that purports to consist of Rochester’s work, but it also contains one of just three surviving copies of his play Lucina’s Rape.

A further 31 poems––half of which are jeux d’espritof a few lines, but which also include longer works such as ‘In the Isle of Brittain’, Seigneur Dildoe and the unfinished ‘What vaine unnecessary things are men’––are not to be found in any of the collections cited above but are scattered in individual manuscript miscellanies and printed collections from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. The most important manuscripts in this group are Nottingham University MS Portland Pw V 31,12 which include the poems in Rochester’s hand, and two manuscripts

which contain corrections in the hand of Rochester’s mother: BL Add. MS 28692 (which contains Lucina’s Rape) and a copy of Upon Nothing in National Archives, Box C 104/110.

Lacking a single basic reliable text, the editor of Rochester has to make his or her own rules. It is hardly possible to present a printed transcription of a manuscript which represents that manuscript faithfully in every respect. Choices have continually to be made. If superscript letters are printed above the line, where should those letters that seem only half-way above it be printed? Again, some scribes will write S and C for initial s and c almost ( but never completely) throughout a poem, their Ss and Cs varying in size from full capitals to small letters. Yet again, in an attempted diplo-matic transcription a few poems would come out, in an extreme case, with lines like this:

I’ th Isle of Britaine Long since famous growne ffor Breedinge

y. Best C.tts. In Xtendome

Their Reigns (& oh Long May hee Reigne & there The easiest king & Best Bred Man alive

him no Ambition Mooves, To Gett Renowne Like The french foole To wandr. up & Downe

( Bod. MS Rawl. D. 924)

11 See Harold Love, ed., The Works of John Wilmot Earl of Rochester(Oxford, 1999), p. xxxvii; ‘Rochester: A Tale of Two Manuscripts’, Yale University Library Gazette, 72 (1997), 41–53, p. 49.

This would be intolerable. And so, while a few contractions have been retained which are still in use today, such as ‘2d’ for second, instances of scribal contractions, amper-sands, and the like have been silently expanded; ‘∫’ ( long s) has been silently ordered to ‘s’, ‘β’ to ‘ss’, and ‘VV’ to ‘W’, and in accordance with modern usage, the letters ‘v’ and ‘u’, and ‘i’ and ‘j’ have been interchanged. All dates are given in Old Style, except that the year is presumed to begin on 1 January, and not 25 March. These apart, all departures from the copy-text have been recorded in the textual notes; for reasons of space, the reader is referred to Love’s edition for the source of the emendations. There can be no certainty, except in a few cases, that Rochester’s own spelling or punctuation has been reproduced. The poems in Rochester’s holograph, and a few of the copy-texts, have almost no punctuation; here these have been punctuated lightly, relying on the reader’s prompt appreciation that the convention was for a line to be end-stopped, regardless of the absence of punctuation, unless the sense made it inappropriate. Capitals and italics may also cause the modern reader difficulty, for although the seventeenth-century convention was for key words to be emphasised in this way, scribes and printers were often erratic both in their observance of what was on the sheet before them, and in their individual style. In fact, there is no entirely satisfactory way, or via media, for a modern editor to present the manuscript text: too much intrusion might well obscure the author’s original intention, whereas too little can leave a passage incomprehensible. The editorial principle followed in the presentation of the texts has been for them to be presented with the minimum of interference, and essentially in order to aid comprehension, so that the reading experience is potentially as similar as possible to that of Rochester’s contemporary readers. In reality, this will be impossible, because reading and declamatory habits have greatly changed during the intervening centuries, but it is hoped nonetheless that the vitality and directness of the texts as they were first encountered, will be transmitted and enjoyed. In the absence of a holograph or a printed text overseen by the author, there can be no certainty that what is here reproduced is what Rochester wrote or intended but, importantly, the poems here are presented in versions that were read in his lifetime.

Rochester apparently ‘published’ his poems either by giving copies to his friends or by leaving them anonymously in what was called the ‘Wits’ drawing room’ (one of the public rooms) in the Palace of Whitehall. There is also the possibility pro-posed by Love that Rochester assembled collections of his songs in the form of a small manuscript liber carminum either for presentation to ‘a patron, client or lover’ or for use by musicians.13 In turn these copies were reproduced, with some texts

falling into the hands of collectors or suppliers of professional scriptoria,14and so

13 ‘The Scribal Transmission of Rochester’s Songs’, Bibliographical Society of Australia and New Zealand, 20 (1996), 161–80, pp. 165–6, 177.

multiplying: BL Harl. 7316, to provide one example, seems to derive directly from Nottingham University MS Portland Pw V 31, and, interestingly, the manuscript texts of Satire against Mankind in Bodleian Library MS Eng. misc. e 536 and the Ottley papers in the National Library of Wales have been identified by Love as being copied from printed versions (the former from 1680 and the latter from either the broad-side or from1691 (Love, p. 565). Doubtless only a small fraction of the once extant manuscript copies of any given poem have survived.

Only about 25 per cent of the texts that Walker selected are reprinted here. He based his choice, as David Vieth had for his groundbreaking edition of 1968, on ver-sions in the professionally produced Yale MS Osborn b 105 and its derivative Poems on Several Occasions By the Right Honourable, the E. of R—, printed in 1680. Love, for his edition, drew on a much wider range of manuscripts than either Vieth or Walker had accessed, and tended to prefer texts that had been prepared for, or obtained by, private collectors. He was able to make use of two previously unknown, but import-ant and extensive, manuscript collections of the ‘politer’ poems: the ‘Hartwell’ MS (now Yale MS Osborn b 334) and the ‘Harbin’ MS (owned by the Marquess of Bath). Both of these derive from a common source, now lost, which lies behind Tonson’s respectable edition of 1691, and conceivably had been prepared by or for Rochester’s niece, Anne Wharton; whereas Love drew extensively on the texts of the ‘Hartwell’ MS, the present edition has chosen to use the ‘Harbin’ MS in order to bring an equally significant manuscript into the wider domain. Love’s favouring of ‘private’ texts rather than scriptorium texts has been continued, and further developed, here, by the selec-tion of the text of Upon Nothing that Rochester’s mother altered, and by drawing more extensively on the collection assembled by the highly placed courtier Sir William Haward (Bodleian MS Don. b 8).

For the text of Lucina’s Rape, both Love and this edition use the British Library manuscript with its two corrections by Rochester’s mother. Hitherto virtually ignored by scholars, the text is here presented in a format that for the first time makes Rochester’s alterations to John Fletcher’s The Tragedie of Valentinian (1613 or 1614) immediately recognisable to the reader.

Canon

Pinto prints 67 firm attributions together with 21 ‘Doubtful’ poems in his edition of 1953, whereas Vieth includes 75 poems in his main section and an additional eight possibles. Subsequently, Walker included in his edition 83 pieces plus five possibles, Paddy Lyons 105 attributions in his, Frank Ellis 92, and most recently Love selected 75 poems as being ‘probably’ by Rochester, together with five ‘Disputed’ pieces.15

Consensus, therefore, is not to be expected.

In this edition, Love (who agrees with Walker in the majority of his attributions) is followed both in his consignment ofSatyr. [Timon], ‘Seigneur Dildo’ and ‘Fling this useless Book away’ to the section of poems less certainly attributable to Rochester, and also in the inclusion among the firm attributions of the poem ‘Out of Stark love and arrant devotion’. However, the six impromptus ‘God bless our good and gra-cious King’, ‘Here’s Monmouth the wittiest’, ‘I John Roberts’, ‘Lorraine you stole’, ‘Poet who e’re thou art’ and ‘Sternhold and Hopkins’ continue to be listed as authentic, rather than among Love’s disputed items. One further impromptu (‘Your husband tight’) has been added to the firm attributions. Computational analyses by John Burrows, which Love includes in his edition, raise plausible concerns about the authenticity of Tunbridge Wells, but whereas Love includes it amongst the firm attri-butions, the case for including it among the ‘less certain’ attributions is more com-pelling, and so it is now treated. An Allusion to Tacitus (‘The freeborn English Generous and wise’), omitted by Walker but whose authenticity is strongly advanced by its presence in the ‘Hartwell’ and ‘Harbin’ MSS, would have been treated as genuine but for another computational analysis, and therefore is only included with the weaker attributions. For this edition, the section of poems that evidences Rochester’s anti-pathy towards Mulgrave and Scroope has been slightly expanded and, finally, with the exception of ‘Out of Stark Love, and arrant Devotion’, the poems that Walker previously listed as being ‘possibly’ by Rochester have been omitted altogether.

Annotation

The notes to this edition seek to explain historical references, to explain words that have moved in meaning since the seventeenth century, and to begin to plot the dense network of allusion in Rochester’s poems. The notes to each poem are divided as follows: where it is appropriate, notes on individual words or lines are followed by a general comment about the context or tradition of a particular poem; a summary version of the evidence for attributing the poem to Rochester; a possible date in those few cases where there is evidence; and details of first publication.

Rochester invented the formal ‘allusion’ much practised later by Pope, but throughout his poetry, of whatever kind, there is local allusion at work. A minor

adjustment, involving very few words, might be said to be Rochester’s characteristic mode:

Her Hand, her Foot, her look’s a Cunt

This vigorous line (in Rochester’s poetry, private parts are always assuming a life of their own, detached from the body) becomes something more when read against the words from Dryden’s Conquest of Granadawhich it parodies:

Her tears, her smiles, her every look’s a Net Parodying Waller on Saint James’s Park,

Bold sons of earth that thrust their arms so high As if once more they would invade the sky . . . Rochester creates something memorably fantastical:

. . . Rows of Mandrakes tall did rise

Whose lewd Topps Fuckt the very Skies . . .

Rochester adjusts the tradition of the cavalier love-lyric, whose conventions were becom-ing tired, and not always by the addition of a consciously brutal obscenity, as the reader will discover if he turns to ‘Phillis, be gentler I advise’ and Treglown’s article to which reference is made in the notes.

Arrangement of this Edition

gathering is instructive, revealing the rangewithin types of Rochester’s poems, espe-cially the satirical, and it obviously makes more sense to gather in one section the flytings between Rochester and Scroope and Rochester and Mulgrave. Where pos-sible, the poems within each section have been ordered chronologically.16

Keith Walker, revised Nicholas Fisher

Further Reading

Editions

Poems on Several Occasions By the Right Honourable, the E. of R—([ London], 1680)

Poems, &c. on Several Occasions: with Valentinian, A Tragedy. Written by the Right Honourable John Late Earl of Rochester ( London, 1691)

Collected Works of John Wilmot Earl of Rochester, ed. John Hayward ( London, 1926)

Rochester’s Poems on Several Occasions, ed. James Thorpe (Princeton, 1950)

The Gyldenstolpe Manuscript Miscellany of Poems by John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, and other Restoration Authors, ed. Bror Danielsson and David M. Vieth (Stockholm, 1967)

The Complete Poems of John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, ed. David M. Vieth ( New Haven and London, 1968)

The Letters of John Wilmot Earl of Rochester, ed. Jeremy Treglown (Oxford, 1980)

Lyrics & Satires of John Wilmot Earl of Rochester, ed. David Brooks (Sydney, 1980)

John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester: Selected Poems, ed. Paul Hammond ( Bristol, 1982)

Rochester: Complete Poems and Plays, ed. Paddy Lyons ( London, 1993)

John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester: The Complete Works, ed. Frank H. Ellis ( Harmondsworth, 1994)

The Works of John Wilmot Earl of Rochester, ed. Harold Love (Oxford, 1999)

Singing to Phillis: Settings of Poems by the Earl of Rochester (1647– 80), ed. Steven Devine and Nicholas Fisher (Huntingdon, 2009)

Biography

Burnet, Gilbert, Some Passages of the Life and Death Of the Right Honourable John Earl of

Rochester, who Died the 26th of July, 1680( London, 1680)

Parsons, Robert, A Sermon Preached at the Funeral of the Rt Honorable John Earl of Rochester, who Died at Woodstock-Park, July 26, 1680, and was Buried at Spilsbury in Oxford-shire, Aug. 9(Oxford, 1680)

Pinto, Vivian de Sola, Enthusiast in Wit: A Portrait of John Wilmot Earl of Rochester 1647–1680

Greene, Graham, Lord Rochester’s Monkey: Being the Life of John Wilmot, Second Earl of Rochester

( London, 1974)

Adlard, John, The Debt to Pleasure (Manchester, 1974)

Lamb, Jeremy, So Idle a Rogue: The Life and Death of Lord Rochester ( London, 1993)

Johnson, James William, A Profane Wit: The Life of John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester (Rochester, 2004)

Critical Studies

Vieth, David M., Attribution in Restoration Poetry: A Study of Rochester’s Poemsof 1680(New Haven and London, 1963)

Erskine-Hill, Howard, ‘Rochester: Augustan or Explorer?’, in G. R. Hibbard, ed., Renaissance

and Modern Essays Presented to Vivian de Sola Pinto in Celebration of his Seventieth Birthday

( London and New York, 1972)

Righter, Anne, ‘John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester’, Proceedings of the British Academy, LIII (1967), 46–69

Farley-Hills, David, Rochester: The Critical Heritage ( London, 1972)

Griffin, Dustin, Satires Against Man: The Poems of Rochester (Berkeley, Los Angeles and

London, 1973)

Farley-Hills, David, Rochester’s Poetry( London, 1978)

Treglown, Jeremy, ed., Spirit of Wit: Reconsiderations of Rochester(Oxford, 1982)

Walker, Robert G., ‘Rochester and the Issue of Deathbed Repentance in Restoration and Eighteenth-Century England’, South Atlantic Review, 47(1) (1982), 21–37

Vieth, David M., ed., John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester: Critical Essays( New York, 1988)

Vieth, David M. and Dustin Griffin, Rochester and Court Poetry( Los Angeles, 1988)

Carver, Larry, ‘Rochester’s Valentinian’, Restoration and Eighteenth Century Theatre Review, 4 (1989), 25–38

Thormählen, Marianne, Rochester: The Poems in Context (Cambridge, 1993)

Burns, Edward, ed., Reading Rochester ( Liverpool, 1995)

Love, Harold, ‘The Scribal Transmission of Rochester’s Songs’, Bibliographical Society of

Australia and New Zealand, 20 (1996), 161–80

Love, Harold, ‘Refining Rochester: Private Texts and Public Readers’, Harvard Library

Bulletin, 7 (1996), 40–9

Coomb, Kirke, A Martyr for Sin: Rochester’s Critique of Polity, Sexuality, and Society(Newark and London, 1998)

Fisher, Nicholas, ed., That Second Bottle: Essays on John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester(Manchester, 2000)

Greer, Germaine, John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester(Horndon, 2000)

Ellenzweig, Sarah, ‘The Faith of Unbelief: Rochester’s Satyre, Deism, and Religious

Freethinking in Seventeenth-century England’, Journal of British Studies, 44 (2005), 27– 45 Fisher, Nicholas, ‘Rochester’s Contemporary Reception: The Evidence of the Memorial Verses’,

Restoration: Studies in English Literary Culture, 1660 –1700, 30 (2006), 1–14

Fisher, Nicholas, ‘Manuscript Miscellanies and the Rochester Canon’, English Manuscript Studies 1100 –1700, 13 (2007), 270 –95

Fisher, Nicholas, ‘Mending What Fletcher Wrote: Rochester’s Reworking of Fletcher’s

Valentinian’, Script & Print, Special Issue, vol. 33(1–4) (2009), 61–75

Bibliography

Prinz, Johannes, John Wilmot Earl of Rochester: His Life and Writings ( Leipzig, 1927)

Vieth, David M., Rochester Studies, 1925–1982: An Annotated Bibliography ( New York and

London, 1984) (This thorough record invaluably includes summaries of the contents of the books and articles noted; the semi-annual journal Restoration: Studies in English Literary Culture, 1660 –1700has a section that details recent publications.)

Background

Sprague, Arthur Colby, Beaumont and Fletcher on the Restoration Stage (Cambridge, MA, 1926)

Ogg, David M., England in the Reign of Charles II(Oxford, 1955)

Lord, George deF. et al., eds, Poems on Affairs of State: Augustan Satirical Verse 1660 –1714 ( New Haven, 1963–75)

Love, Harold, ed., Restoration Literature: Critical Approaches (Oxford, 1972)

Hume, Robert D., The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century(Oxford, 1976)

Redwood, John, Reason, Ridicule and Religion: The Age of Enlightenment in England 1660 –1750

( London, 1976)

Picard, Lisa, Restoration London( London, 1977)

Thompson, Roger, Unfit for Modest Ears: A Study of Pornographic, Obscene and Bawdy Works

Written or Published in England in the Second Half of the Seventeenth Century( London, 1979) Rawson, Claude, ed., English Satire and the Satiric Tradition(Oxford, 1984)

Hill, Christopher, The Collected Essays of Christopher Hill: Volume I, Writing and Revolution in 17th Century England (Amherst, 1985)

Hutton, Ronald, The Restoration: A Political and Religious History of England and Wales

1658–1687 (Oxford, 1985)

Spurr, John, The Restoration Church of England, 1646–1689 ( New Haven and London, 1991)

Beal, Peter, Index of English Literary Manuscripts. Volume II 1625–1700( London, 1993) Love, Harold, Scribal Publication in Seventeenth-Century England (Oxford, 1993)

Manning, Gillian, ‘Rochester’s Satyr against Reason and Mankind and Contemporary

Religious Debate’, The Seventeenth Century, 8 (1993), 99–121

Spurr, John, ‘Perjury, Profanity and Politics’, The Seventeenth Century, 8 (1993), 29–50

Coward, Barry, The Stuart Age: England, 1603–1714, 2nd edn ( London, 1994)

Brennan, Michael and Paul Hammond, ‘The Badminton Manuscript: A New Miscellany of Restoration Verse’, English Manuscript Studies 1100–1700, 5 (1995), 171–207

Chernaik, Warren, Sexual Freedom in Restoration Literature (Cambridge, 1995)

Zimbardo, Rose, At Zero Point: Discourse, Culture, and Satire in Restoration England ( Lexington, 1998)

Burrows, John and Harold Love, ‘Attribution Tests and the Editing of Seventeenth-Century Poetry’, The Yearbook of English Studies, 29 (1999), 151–75

Marotti, Arthur F. and Michael D. Bristol, Print, Manuscript and Performance: The Changing

Relations of the Media in Early Modern England (Columbus, 2000)

Miller, John, After the Civil Wars: English Politics and Government in the Reign of Charles II (Harlow, 2000)

Turner, James Grantham, Libertines and Radicals in Early Modern London: Sexuality, Politics and Literary Culture, 1630 –1685(Cambridge, 2002)

Love, Harold, Attributing Authorship: An Introduction(Cambridge, 2002)

Turner, James Grantham, Schooling Sex: Libertine Literature and Erotic Education in Italy,

France, and England, 1534–1685(Oxford, 2003)

Love, Harold, English Clandestine Satire 1660–1702(Oxford, 2004)

Harris, Tim, Restoration: Charles II and His Kingdoms 1660–1685 ( London, 2005)

Hammond, Paul, The Making of Restoration Poetry( Woodbridge, 2006)

Tilmouth, Christopher, Passion’s Triumph over Reason: A History of the Moral Imagination from

Spenser to Rochester (Oxford, 2007)

Rosenfeld, Nancy, The Human Satan in Seventeenth-Century English Literature: From Milton to

Abbreviations

1680 Poems On Several Occasions By the Right Honourable The E. of R— (Antwerp [London], 1680)

1691 Poems &c. On Several Occasions: With Valentinian, A Tragedy. Written by the Right Honourable John Late Earl of Rochester (London, 1691)

Attribution David M. Vieth, Attribution in Restoration Poetry: A Study of Rochester’s Poems of 1680 (New Haven and London, 1963)

BL British Library, London

Bodleian Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

Chetham’s Library of Chetham’s School of Music, Manchester

Court Satires John Harold Wilson, Court Satires of the Restoration (Columbus, 1976) Ellis John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester: The Complete Works, ed. Frank H.

Ellis (London, 1994)

Fisher Quarto miscellany owned by Nicholas Fisher Folger Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington

Griffin Dustin H. Griffin, Satires Against Man: The Poems of Rochester (Berkeley, Los Angeles & London, 1973)

Gyldenstolpe The Gyldenstolpe Manuscript Miscellany of Poems by John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, and other Restoration Authors, ed. Bror Danielsson and David M. Vieth (Stockholm, 1967)

Hammond John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester: Selected Poems, ed. Paul Hammond (Bristol, 1982)

Harvard Houghton Library, Harvard University

Leeds The Brotherton Collection, Leeds University Library

Letters The Letters of John Wilmot Earl of Rochester, ed. Jeremy Treglown (Oxford, 1980)

Longleat Thynne Papers Vol. XXVII in the Library of the Marquess of Bath, Longleat House, Warminster, Wiltshire

MLR The Modern Language Review N&Q Notes and Queries

OED The Oxford English Dictionary, ed. John Simpson & Edmund Weiner, 2nd ed., 20 vols (OUP, 1989)

Osborn The James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University POAS Poems on Affairs of State: Augustan Satirical Verse, 1660 –1714, ed.

George deF Lord et al., 7 vols (New Haven & London, 1963–75) PBSA Proceedings of the Bibliographical Society of America

PQ Philological Quarterly

Pinto, Enthusiast Vivian de Sola Pinto, Enthusiast in Wit: A Portrait of John Wilmot Earl of Rochester 1647–1680(London, 1962)

Poems, Pinto Poems by John Wilmot Earl of Rochester, ed. Vivian de Sola Pinto (London 1953; 2nd edition, 1964)

Princeton Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library

RES Review of English Studies

Some Passages Gilbert Burnet, Some Passages of the Life and Death Of the Right Honourable John Earl of Rochester, Who died the 26th of July, 1680 (London, 1680)

Spirit of Wit Spirit of Wit: Reconsiderations of Rochester, ed. Jeremy Treglown (Oxford, 1982)

Thormählen Marianne Thormählen, Rochester: The Poems in Context (Cambridge, 1993)

Vieth The Works of The Earl of Rochester, ed. David M. Vieth (London and New Haven, 1968)

Walker The Poems of John Wilmot Earl of Rochester, ed. Keith Walker (Oxford, 1984)

Waller Miscellany owned by Richard Waller

Juvenilia

To His Sacred Majesty

Vertues triumphant Shrine! who do’st engage At once three Kingdomes in a Pilgrimage; Which in extatick duty strive to come

Out of themselves as well as from their home;

Whilst England grows one Camp, and Londonis 5

It self the Nation, not Metropolis; And loyall Kentrenews her Arts agen,

Fencing her wayes with moving groves of men; Forgive this distant homage, which doth meet

Your blest approach on Sedentary feet: 10

And though my youth, not patient yet to bear The weight of Armes, denies me to appear In Steel before You, yet, Great Sir, approve My manly wishes, and more vigorous love;

In whom a cold respect were treason to 15

A Fathers ashes, greater than to you; Whose one ambition ’tis for to be known, By daring Loyalty Your WILMOT’s Son.

ROCHESTER. Wadh. Coll.

3–4 extatick duty . . . Out of themselves: playing on the etymological sense of ‘ecstasy’ from Greek eksistanai‘to put out of place’.

10 Sedentary feet: Rochester responds to Charles II’s approach with lame(?) verse (feet).

Authorship: Attributed to Rochester in the copy-text and again in 1691. Love puts the poem in a section of ‘Poems probably by Rochester’, but notes Anthony à Wood’s claim ‘these three copies were made [ Wood is speaking also of “Impia blasphemi” and “Respite great Queen”], as ’twas then well known, by Robert Whitehall a physician of Merton college, who pretended to instruct the count (then twelve years of age) in the art of poetry’ (Athenæ Oxonienses(London, 1691–2), ii, col. 656). While Whitehall may have added polish, there is ‘nothing in them that might not have been composed by a clever boy of thirteen’ (Pinto,

Enthusiast, p. 9) and the case for Whitehall’s authorship is further weakened by the attack on physicians in To Her Sacred Maty. the Queen Mother(ll. 31– 44) and by the

undergradu-ate style of the opening line of ‘Impia blasphemi’.

Date: May 1660. Charles arrived back in England on 25 May 1660 to a rapturous reception.

Copy-text: Britannia Rediviva (Oxford, 1660), sig. Aa1r–v.

First publication: As copy-text.

Departure from copy-text: [italics reversed].

[Impia blasphemi]

Impia blasphemi sileant convitia vulgi: Absolvo medicos, innocuamque manum. Curassent alios facili medicamine morbos:

Ulcera cùm veniunt, Ars nihil ipsa valet.

Vultu fœmineo quævis vel pustula vulnus 5

Lethale est; pulchras certior ense necat. Mollia vel temeret si quando mitior ora,

Evadet forsan fœmina, Diva nequit.

Cui par est animæ Corpus, quæ tota venustas,

Formæ quî potis est hæc superesse suæ? 10

Johan, Comes Roffen. è Coll. Wadh.

1 Love, noting that this is modelled on Martial, De Spectaculis Liber, i.1: ‘Barbara pyramidum sileat miracula Memphis’, describes this as ‘a trick more suggestive of the very young under-graduate, Rochester, than the well-read Whitehall’ (Love, p. 436).

This, and the following poem (‘Respite great Queen’), were first printed in a collection of verses in Greek, Latin, Hebrew, and English on the death of Mary, Princess Royal of England and Princess of Orange, from smallpox on Christmas Eve, 1660.

Authorship: Attributed to Rochester in the copy-text and in 1691. And see the note to ‘Vertues triumphant Shrine!’ above.

Date: Shortly after 24 December 1660.

Copy-text: Epicedia Academiæ Oxoniensis, in Obitum Serenissimæ Mariæ Principis Arausionensis

(Oxford, 1661), [sig. A2v].

First publication: As copy-text.

Departures from copy-text: [italics reversed] 2 innocuamque] innocuamq;

To Her Sacred Ma

ty. the Queen Mother

Respite great Queen your just and hasty fears, Ther’s no infection lodges in our teares. Though our unhappy aire be arm’d with death, Yet sigh’s have an untainted guiltlesse breath.

O! stay a while, and teach your equall° skill fair, just, impartial(= Lat. æquus) 5 To understand and to support our ill°. i.e., recognise and help us to endure our sense

You that in mighty wrongs an Age have spent, [of calamity

And seem to have out-liv’d even bannishment: Whom traiterous mischeif sought its earliest prey,

When unto sacred blood it made its way; 10

And thereby did its black designe impart, To take his head, that wounded first his heart: You that unmov’d great Charleshis ruine stood, When that three Nations sunk beneath the load:

Then a young Daughter lost, yet balsome found 15

To stanch that new and freshly bleeding wound: And after this with fixt and steddy eyes

Beheld your noble Glocesters obsequies: And then sustain’d the royall Princess fall;

You only can lament her Funerall. 20

But you will hence remove, and leave behind

TitleQueen Mother: the widow of Charles I, Henrietta Maria, whose daughter Mary, Princess of Orange, had died of smallpox on Christmas Eve 1660.

9–12 Vieth identified this allusion to the impeachment of the Queen by the House of

Commons in May 1643 (Vieth, p. 157).

15 young Daughter: Elizabeth, second daughter of Charles I, died in September 1650.

18 Glocesters: Henry, Duke of Gloucester, third son of Charles I. He died in September

1660.

Our sad complaints lost in the empty wind; Those winds that bid you stay, and loudly rore Destruction, and drive back unto the Shore:

Shipwrack to safety, and the envy fly 25

Of sharing in this Scene of Tragedy:

Whilst sickness from whose rage you post away Relents, and only now contrives your stay: The lately fatall and infectious ill

Courts the fair Princesse and forgets to kill. 30

In vain on feavors curses we dispence, And vent our passions angry eloquence: In vain we blast the Ministers of Fate, And the forlorne Physitians imprecate,

Say they to death new poisons adde and fire; 35

Murder securely for reward and hire; Arts Basilicks, that kill whom ere they see, And truly write bills of Mortality;

Who least the bleeding Corps should them betray,

First draine those vitall speaking streames away. 40 And will you by your flight take part with these?

Become your self a third and new disease? If they have caus’d our losse, then so have you, Who take your self and the fair Princesse too:

For we depriv’d, an equall damage have 45

When France doth ravish hence as when the grave. But that your choice th’unkindness doth improve, And dereliction adds unto remove.

Rochester of WadhamColledge.

Authorship: Attributed to Rochester in the copy-text and in 1691. But see the note to ‘Vertues triumphant Shrine!’ above.

Date: Probably January 1661. See note to line 21.

Copy-text: Epicedia Academiæ Oxoniensis, in Obitum Serenissimæ Mariæ Principis Arausionensis

(Oxford, 1661), sig. G1r–v.

First publication: As copy-text.

Departures from copy-text: [italics reversed] 31 curses] cures

30 fair Princesse: Henrietta Anne, afterwards Duchess of Orleans.

37 Basilicks: OED(basilisk 1) quotes A Physical Dictionary(London, 1657): ‘Basilisk . . . kills a man with its very sight (as some say) . . .’.

19–30 Inspired by the much-imitated simile of the stream changing course in Donne’s Elegy, ‘Oh let mee not serve so’, lines 21–34, itself derived from Horace, Carmina, III. xxix. 33– 41, as Love points out ( p. 349).

Love Poems

The Advice

All things submit themselves to your Command, Fair Celia, when it does not Love withstand The pow’r it borrowes from your Eyes alone, All but himself must yeild to who has none,

Were he not blind such are the charms you have 5

Hee’d quit his Godhead to become your Slave, Be proud to Act a Mortall Heroes part

And Throw himself for fame on his own Dart But fate has otherwise dispos’d of things,

In different bonds subjected Slaves and Kings, 10

Fetterd in form of royall state are they, while we enjoy the fredome to obey. That fate ( like you resistless) does ordain To Love that over Beauty he shall Reign,

By Harmony the Universe does move 15

And what is Harmony but Mutuall Love Who would resist an Empire so Divine Which Universall nature does enjoyne. See gentle Brooks how quietly they Glide

Kissing the Rugged banks on either side 20

And with them feed, the flowers, which they bestow Tho’ rudely throng’d by a too near Embrace

In Gentle murmurs they keep on their pace

To the lov’d Sea, for even Streams have their desires, 25 Cold as they are, they feel loves pow’rfull fires,

And with such passion that if any force,

Stopp, or molest them in their amorous course, They Swell, Break down with rage, and ravage o’er

The banks they kiss’d, the flowers they fed before. 30 Submit then Celia e’re you be reduc’d,

For Rebels vanquish’d once are viely us’d. Beauty’s no more but the dead Soil which love Manures, and does by wise commerce improve,

Sailing by sighs thro’ seas of tears he sends 35

Courtship from foreign hearts: for your own Ends

Cherish a trade, for as with Indians° we natives of America, West Indies or India

Get gold and jewells for our Trumpery. So to each other for their useless toys

Lovers afford whole magazines° of joys. warehouses, storehouses 40

But if you’r fond of Baubles, be, and starve,

Your Gue Gaw° reputation still preserve, i.e., gewgaw(paltry thing without value, trifle)

Live upon modesty and empty fame,

Forgoing sense for a fantastick° Name. fanciful, capricious, arbitrary

Authorship: Attributed to Rochester in 1691.

Date: Before 28 October 1671, when it was entered in the Stationers’ Register.

Copy-text: Longleat, ‘Harbin’ MS, f. 54r–v.

First publication: A Collection of Poems, Written upon several Occasions, By several Persons. Never Before in Print (London, 1672).

Departures from copy-text: 14 Reign] Reing 22 feed] feed, 27 force] force, 35 sighs] sight 36 foreign] forreing

31 reduc’d: ‘A technical term for the conquest through siegeworks of a fortified town’ (Love, p. 349).

40 Jeremy Treglown writes: ‘the “magazines of joyes” . . . which are seen . . . as the reward of the sexual activity being urged on Celia, derive from the language of courtly adoration repeatedly employed in the poem to disguise an aggressive assertion of male superiority’.

Treglown quotes Every Man out of his Humour, II. iii. 26–27, and Lord Herbert of Cherbury’s

‘A Description’, lines 51–4, as more straightforward uses of the figure (see ‘The Satirical

Inver-sion of Some English Sources in Rochester’s Poetry’, Review of English Studies, 24 (1973),

12 Like Blazing Commets in a Winters Sky: ‘the great comet of 1664 –5 was first observed on 7 November 1664 in Spain. Pepys saw it on 24 November 1664. . . . In the midst of all this excitement Rochester returned to England from his Grand Tour’ (Ellis, p. 312). The other comets of the reign appeared during spring or summer.

The Discovery

Cælia, that faithfull Servant you disown, Wou’d in obedience keep his love unknown, But bright Ideas such as you inspire

We can no more conceal, than not admire.

My heart at home in my own Breast did dwell, 5

Like Humble Hermit in a Peacefull Cell Unknown and undisturb’d it rested there, Stranger alike to hope, and to despair. Now Love with a tumultuous traine invades,

The sacred quiet of those Hallow’d Shades, 10

His fatall flames shine out to ev’ry Eye, Like Blazing Commets in a Winters Sky How can my passion merrit your offence

That Challenges° so little recompence, demands

For I am one born only to admire, 15

Too Humble e’re to hope, scarce to desire A thing whose Bliss depends upon your will Who wou’d be proud you’d deign to use him Ill. Then give me leave to glory in my chain

My fruitless Sighs and my unpitty’d pain 20

Let me but ever Love and ever be The example of your pow’r and Cruelty, Since so much Scorn does in your Breast reside, Be more indulgent to its mother pride,

Kill all you strike and trample on their graves, 25

But own the fates of your neglected Slaves. When in the Crowd yours undistinguish’d lyes, You give away the triumph of your Eyes, Perhaps (obtaining this) you’ll think I find

More mercy than your Anger has dezing’d, 30

But Love has carefully contriv’d for me The last perfection of Misery.

My worst of fates attends me in my grave, 35 Since dying I must be no more your Slave.

Authorship: Attributed to Rochester in 1691.

Date: Before 28 October 1671, when it was entered in the Stationers’ Register.

Copy-text: Longleat, ‘Harbin’ MS, ff. 54v–55r.

First publication: A Collection of Poems, Written upon several Occasions, By several Persons. Never Before in Print (London, 1672).

Departures from copy-text: 18 omitted; text from ‘Hartwell’ MS 20 My] Thy 30 design’d] desing’d

The Imperfect Enjoyment

Nakedshe lay clasp’d in my longing Armes I fill’d with Love and she all over Charmes Both equally inspir’d with eager fire

Melting through kindness flameing in desire.

With Armes, Leggs, Lipps, close clinging to embrase 5 She clipps° me to her Breasts and sucks me to her face. clasps

Her nimble tongue (loves lesser lightning) plaied Within my Mouth; and to my heart conveyd Swift Orders, that I might prepare to throw

The all dissolving Thunderbolt beloe. 10

My fluttering soul, sprung with the pointed Kiss Hangs hovering o’re her balmy brinks of bliss But whilst her buisy hand would guide that part Which shou’d convey my soul up to her heart

In liquid raptures I dissolve all o’re 15

Melt into sperm and spend at every pore. A touch from any part of her had don’t Her hand, her foot, her very look’s a C—t.

Title: A seventeenth-century genre of poems about untimely sexual incapacity is charted by Richard E. Quaintance, ‘French Sources of the Restoration “Imperfect Enjoyment” Poem’,

Philological Quarterly, 42 (1963), 190–9. For English examples see George Etherege’s ‘The

Imperfect Enjoyment’ (Poems, ed. James Thorpe (Princeton, 1963), pp. 7–8), Aphra Behn’s ‘The

Disappointment’, published as Rochester’s in 1680, and Mulgrave’s ‘The Enjoyment’, published

as a broadside in 1679. The genre ultimately stems from Ovid,Amores, III. vii, to which Rochester’s poem seems directly indebted.

11 sprung: ‘To spring a bird is to make it rise from cover’ (Hammond, p. 81).

18 Her hand, her foot, her very look’s a C — t: Jeremy Treglown points out the parody of

Dryden’s Conquest of Granada (1672), I, III.i.71: ‘Her tears, her smiles, her every look’s a Net’,

which was first performed in December 1670 (‘Rochester and Davenant’, N&Q, 221 (1976),

![Figure 2.Title-page of Poems on Several Occasions By the Right Honourable, The E. of R—(Antwerp [London], 1680) (Pepys Library, Magdalene College, Cambridge)](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok/3928114.1871534/36.485.104.407.78.619/figure-occasions-honourable-antwerp-library-magdalene-college-cambridge.webp)

![Figure 4.Title-page A Satyr against Mankind [London, 1679] (private collection)](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok/3928114.1871534/125.485.55.417.82.620/figure-title-page-satyr-mankind-london-private-collection.webp)