Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 19 January 2016, At: 20:20

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

An economic survey of northern Sulawesi:

turning weaknesses into strengths under regional

autonomy

Lucky Sondakh & Gavin Jones

To cite this article: Lucky Sondakh & Gavin Jones (2003) An economic survey of northern Sulawesi: turning weaknesses into strengths under regional autonomy, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 39:3, 273-302, DOI: 10.1080/0007491032000142755

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0007491032000142755

Published online: 03 Jun 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 77

View related articles

INTRODUCTION

North Sulawesi and Gorontalo became separate provinces only in 2001. They occupy the eastern section of the long northern peninsula of Sulawesi, plus the Sangir Talaud islands which stretch north towards the Philippines (figure 1). Although every region has special features, northern Sulawesi could per-haps claim more than most, notably its location close to the Philippines on the periphery of the Indonesian archipel-ago, its religious composition, and its long history of broad-based education. Its economy is heavily primary indus-try based, with coconuts playing the predominant role. The division of the former North Sulawesi into two provinces occurred just as Indonesia embarked on a radical program of

decentralisation. The purpose of this survey is to describe the economic structure and growth of the region in historical and social context, to discuss the impact of the division, and to make a preliminary assessment of how the two provinces are dealing with the challenges of regional autonomy. Table 1 presents some essential data on the two new provinces.

The two main foci of settlement in the former North Sulawesi province, Minahasa and Gorontalo, have con-trasting history and culture. The peo-ples of Minahasa and Sangir Talaud have long had contact with Europeans, and from the middle of the 16th cen-tury, through Spanish, Portuguese and later Dutch influence, their populations

AN ECONOMIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN SULAWESI:

TURNING WEAKNESSES INTO STRENGTHS

UNDER REGIONAL AUTONOMY

Lucky Sondakh

Universitas Sam Ratulangi, Manado

Gavin Jones

The National University of Singapore and The Australian National University

The separation of North Sulawesi and Gorontalo into two provinces in 2001 com-plicated the issue of making regional autonomy work for northern Sulawesi, a region far removed from Indonesia’s centre of power. Although the region had come through the economic crisis relatively well, the over-reliance on coconuts and the lack of a focus for dynamic development remained a challenge. Tourism, min-ing and services were the most dynamic sectors but, for different reasons, none of these sectors can be relied on for steady long-term growth. With the selection of the corridor from Manado to Bitung as one of Indonesia’s 13 integrated economic development zones (Kapet), and given the new North Sulawesi province’s poten-tial role as a ‘gateway’ to Northeast Asia, the longer-term prospects for this province are brighter than those of Gorontalo. Nevertheless, capitalising on North Sulawesi’s potential remains a formidable challenge.

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/03/030273-30 © 2003 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/0007491032000142755

274

Lucky Sondakh and Gavin Jones

PROPINSI GORONTALO PROPINSI

SULAWESI TENGAH

PROPINSI SULAWESI UTARA

0 25 50 100 150 200 Kilometres

Pohuwato Boalemo Kota Gorontalo

Gorontalo

Bolaang Mongondow

Kota Tomohon Minahasa

Selatan Kota Manado

Minahasa

Kota Bitung Kepulauan

Sangir Talaud

Kepulauan Talaud

Province boundaries

District boundaries

Bone Balango

were largely converted to Christianity. Over the same period, those of Gorontalo and Bolaang Mongondow were largely converted to Islam through the efforts of the sultanate of Ternate. The ‘special relationship’ that developed between the Minahasans and the Dutch was reflected in the much earlier spread of education to a substantial proportion of their popula-tion than occurred anywhere else except Maluku, and in the special role accorded them in the Dutch adminis-tration and army (Jones 1977: 5–9). As a result, the Minahasans are more west-ernised than most other Indonesians. The Christian church plays major roles in the social and economic life of Mina-hasa and Sangir Talaud. Indeed, the Evangelical Church of Minahasa and Sangir Talaud (GMIM, Gereja Masehi Injili Minahasa) is so important in the provision of education, health and wel-fare services that its administrative structure almost parallels that of the provincial government.

These two provinces have been remarkably free of the ethnic and religious conflict plaguing some parts of Indonesia, despite different ethno-religious groups living in close prox-imity, for example, in the cities of Man-ado and Bitung and in many parts of Bolaang Mongondow. But the main concentrations of Christians and Mus-lims are indeed separated, the Chris-tians being concentrated in Minahasa, Manado and Sangir Talaud, and the Muslims in Gorontalo.

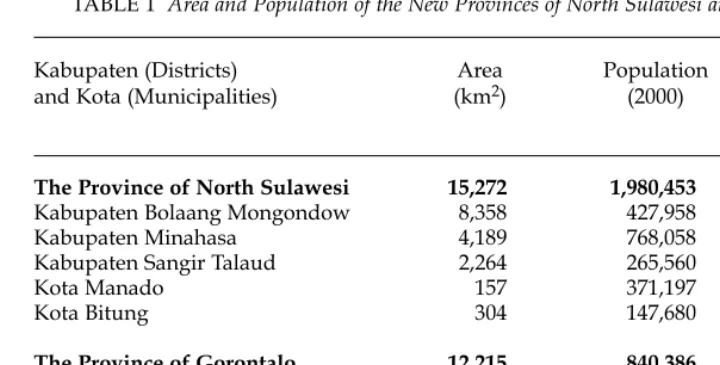

In recent times of political uncer-tainty in Indonesia, when religious antagonisms have been used for politi-cal ends, there is a downside to being one of Indonesia’s few predominantly Christian areas. More than 40,000 refugees from religious violence in Halmahera were accommodated in camps in North Sulawesi for a substan-tial period in 1999–2001. Threats by the (now disbanded) Islamic extremist group Laskar Jihad to kill Christians in Maluku or in Java were noted with TABLE 1 Area and Population of the New Provinces of North Sulawesi and Gorontaloa

Kabupaten (Districts) Area Population Population

and Kota (Municipalities) (km2) (2000) Density

(per km2)

The Province of North Sulawesi 15,272 1,980,453 130

Kabupaten Bolaang Mongondow 8,358 427,958 51

Kabupaten Minahasa 4,189 768,058 183

Kabupaten Sangir Talaud 2,264 265,560 117

Kota Manado 157 371,197 2,361

Kota Bitung 304 147,680 486

The Province of Gorontalo 12,215 840,386 69

Kabupaten Boalemo 6,762 190,279 28

Kabupaten Gorontalo 5,389 515,033 96

Kota Gorontalo 65 135,074 2,084

aBetween the 2000 census and the time of writing three further kabupatenand one new kota

were created (see text and figure 1). Source: BPS Sulut (2001).

some apprehension in North Sulawesi, and indeed some Christian militia groups were formed, albeit without official church sanction (Jacobsen 2002: 22–5).

The former North Sulawesi is peripheral to Indonesia’s political and economic power bases. Manado is closer to Manila than it is to Jakarta, and closer to Davao than it is to Makasar, the main metropolis of East-ern Indonesia. Neither the land area nor the population (both below 1.5% of Indonesia’s total) is large enough to force central government planners to pay much attention, nor is the region seen to be of great political importance. Whereas North Sulawesians played influential roles in the central govern-ment during the post-independence era under Sukarno (with 3–5 ministers in the cabinet), in the Soeharto era the former province had only one cabinet minister, briefly in 1996–97.

This paper traces the administrative changes affecting the two provinces; it then examines population changes and social development, and surveys the structure of and changes in the regional economy. The study con-cludes by considering the challenges posed by regional autonomy, and set-ting out some issues and strategies for the future. The terms ‘northern Sulawesi’ and ‘the former province of North Sulawesi’ are used to refer to the region covered by the two new provinces. Unless otherwise indicated, or unless used in a pre-2001 context, the term ‘North Sulawesi’ refers to the new province of that name.

ADMINISTRATIVE CHANGES

In the new era of regional autonomy, with increased authority given to the second (sub-provincial) level adminis-trative units (kabupatenor districts, and

kota or municipalities), there have been strong pressures towards the creation of new units, in some cases based more on sub-ethnic group sentiment, notions of ‘bringing the government closer to the people’, and politicians’ ambitions, than on economic reason-ing. Prior to 2000, North Sulawesi con-sisted of seven administrative areas: four kabupaten (Sangir Talaud, Mina-hasa, Bolaang Mongondow and Gorontalo) and three kota (Manado, Bitung and Gorontalo). In 2000 the

kabupaten of Gorontalo was divided into two: Gorontalo in the east and Boalemo in the west. More recently, the kabupaten of Sangir Talaud and Boalemo have both been split into two, and Minahasa into three (South Mina-hasa, Minahasa and kota Tomohon).1 Unfortunately, kabupaten that lack a sufficient economic base and enough trained personnel are likely to find autonomy difficult.

Even though the kabupaten level of administration has been given greater focus than the province in the era of regional autonomy, the most crucial recent development is undoubtedly the division of the province of North Sulawesi into two in early 2001. Why did Gorontalo, a small and economi-cally weaker region, want to separate from North Sulawesi? There had always been cultural and religious dif-ferences and rivalries between the Gorontalese and Minahasans. The lat-ter traditionally controlled most aspects of politics, government and business, and many Gorontalese believed that their region’s economic backwardness resulted from imbal-ances in infrastructure and public facil-ities, with good quality schools, uni-versities and hospitals located mainly in the Minahasa–Manado region. Gorontalo, with a population of only 840,000 in 2000, is the least populous

province in Indonesia, apart from North Maluku. Its creation leads to a more ethnically and culturally cohe-sive provincial population.2

Population Change

The population of the former North Sulawesi grew from 0.75 million in 1930 to over 2 million in 1980 and to 2.8 million in 2000. Population growth has slowed in recent years, lying below that in Indonesia as a whole (table 2).

Net migration has not played a sig-nificant role in this population change. The main reason for the slowing of population growth has been sharp declines in fertility rates. The halving of North Sulawesi’s total fertility rate in approximately 13 years to 2.7 in 1985 put the former province in the same league as family planning ‘success sto-ries’ like China, Thailand, Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan and the Republic of Korea (Sondakh and Jones 1989: 377). Within Indonesia, this fertility decline more or less paralleled that in East Java and Bali.3 However, in the decade between 1985 and the mid 1990s, fertility in the former North Sulawesi barely declined at all, and the total fertility rate of 2.6 is still 24% above replacement level (about 2.1). Nevertheless, the small family norm is well and truly entrenched, with 67% of women with two living children and

89% of women with three living chil-dren wanting no more chilchil-dren, the highest proportions in any province outside Java–Bali.

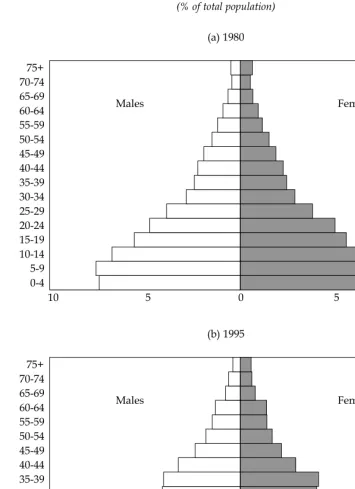

The annual number of births in the province declined sharply from the mid 1970s to the late 1980s, and although it has increased again in recent years as a result of the slacken-ing of fertility decline, there are still perhaps 5% fewer births each year than there were in the mid 1970s. This has had major effects on the popula-tion pyramid (figure 2). In the space of just 15 years, from 1980 to 1995, the age pyramid of northern Sulawesi has been transformed from the traditional high fertility shape (with just the beginnings of an undercutting at the youngest ages) to one of more cylindri-cal shape, reflecting a population structure well on the way to maturity. This is an age structure well placed to reap the rewards of lessened ‘depend-ency’, because numbers in the old age cohorts remain small, numbers of chil-dren are falling, but numbers in the main working ages are rising rapidly. Thus the ratio of ‘dependants’ (roughly defined as those aged 0–14 and 65 and above) to ‘producers’ (roughly defined as those aged 15–64) fell from 0.83 in 1980 to 0.54 in 1995. The benefit is transitional, eventually to disappear as the share of the elderly TABLE 2 Population Growth, Northern Sulawesi and Indonesia

(% p.a.)

Northern Sulawesi Indonesia

1971–80 2.3 2.3

1980–90 1.6 2.0

1990–2000 1.3 1.5

Sources: Calculated from the 1971, 1980, 1990 and 2000 censuses, and the 1995 intercensal survey (Supas).

FIGURE 2 Northern Sulawesi: Age Pyramid (% of total population)

0-4 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75+

-10 -5 0 5 10

Males Females

0-4 5-9 10-14 15-19 20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75+

-10 -5 0 5 10

Males Females

(a) 1980

(b) 1995

Sources: 1980 population census; 1995 Supas.

10 5 0 5 10

10 5 0 5 10

in the population rises. But it is cer-tainly not ephemeral, as the overall dependency ratio is unlikely to begin turning up for another two decades. In the meantime, the age structure favours rapid economic development, provided that sound economic policies are pursued and enough young people are educated to a high level to meet the need for professionals and managers.

The proportion of the population living in urban areas rose from 16.8% in 1980 to 26.3% in 1995. The largest city, Manado, has grown fairly rapidly, more than doubling in population between 1971 and 2000, when its figure of 371,197 placed it in 23rd rank among Indonesian cities. Bitung has also grown quite rapidly. But Gorontalo has grown by less than two-thirds over the same period. This growth would prob-ably have been fully accounted for by natural increase; in other words, there appears to have been negligible net migration to or from the city of Gorontalo.

One long-term trend in population redistribution should be noted. The severe isolation and transportation problems faced by the string of small islands making up Sangir Talaud have been further compounded by land shortage and volcanic eruptions. Lack of roads and irregular sea communica-tion result in local copra prices being less than one-quarter of those in the world market. Many islanders have, not surprisingly, sought the better economic opportunities available in Minahasa–Manado or in coastal fish-ing areas, or the agricultural opportu-nities opened up by improved trans-portation and new settlements in Bolaang Mongondow, notably the Dumoga Valley. Some have moved even further afield, to Halmahera or the southern Philippines. Sangir Ta-laud’s share of the population fell from

22% in 1930 to 10% in 1995. Over the same period, the share of the ‘pioneer-ing’ region of Bolaang Mongondow rose, as did that of the city of Manado.

Social Developments

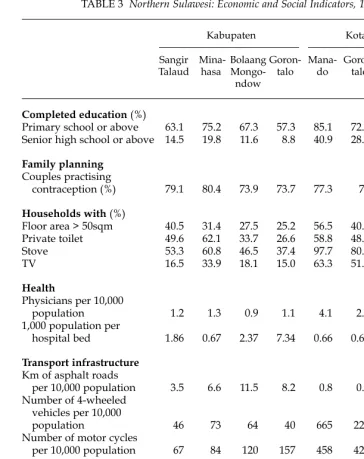

Economic and social conditions vary considerably within the two provinces. Minahasa, including the cities of Man-ado and Bitung, is the wealthiest region, has good levels of education and health, and leads on virtually every socio-economic indicator (table 3). The kabupatenand kotaof Gorontalo rank lower than those in the rest of the region on most of the indicators in table 3.

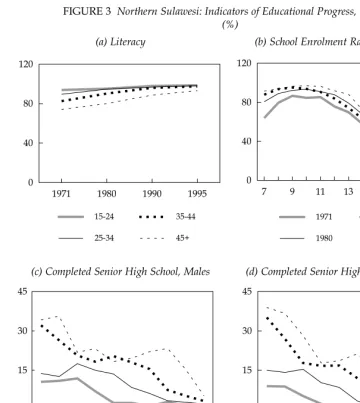

The exceptional level of social devel-opment in northern Sulawesi (espe-cially Minahasa) at the time of inde-pendence has left an important legacy. The tradition of education runs deep in families, and children in Minahasa are much more likely to have educated grandparents than are children in Java. The indicators of educational progress shown in figure 3 all reflect continued improvement over time. Average lev-els of educational attainment in north-ern Sulawesi are better than those in South Sulawesi or in Java, and there is less male advantage in education. At ages over 40, the number of people with junior high school education and above is more than twice as high in northern Sulawesi as in East Java. The contrast is particularly striking in the case of females. The long tradition of female education helps explain the rel-atively high age at marriage for females, the strong representation of Minahasans in well-paying secretarial positions in Jakarta, the success of the family planning program in northern Sulawesi, and the Indonesia-wide rep-utation of Minahasan women for inde-pendence of thought and action (Som-pie-Geru et al. 1999). About half the

TABLE 3 Northern Sulawesi: Economic and Social Indicators, 1995a

Kabupaten Kota Total Sangir Mina- Bolaang Goron- Mana- Goron- Bitung Talaud hasa Mongo- talo do talo

ndow

Completed education (%)

Primary school or above 63.1 75.2 67.3 57.3 85.1 72.8 73.0 69.9 Senior high school or above 14.5 19.8 11.6 8.8 40.9 28.2 25.1 19.2

Family planning Couples practising

contraception (%) 79.1 80.4 73.9 73.7 77.3 77 75.2 76.8

Households with (%)

Floor area > 50sqm 40.5 31.4 27.5 25.2 56.5 40.6 35 30.8

Private toilet 49.6 62.1 33.7 26.6 58.8 48.5 58 47.2

Stove 53.3 60.8 46.5 37.4 97.7 80.1 88.6 60.1

TV 16.5 33.9 18.1 15.0 63.3 51.0 43.5 31.1

Health

Physicians per 10,000

population 1.2 1.3 0.9 1.1 4.1 2.1 0.9 1.6

1,000 population per

hospital bed 1.86 0.67 2.37 7.34 0.66 0.69 0.76 1.12

Transport infrastructure Km of asphalt roads

per 10,000 population 3.5 6.6 11.5 8.2 0.8 0.7 1.3 6.1

Number of 4-wheeled vehicles per 10,000

population 46 73 64 40 665 228 179 159

Number of motor cycles

per 10,000 population 67 84 120 157 458 420 98 177

Economic indicators

Per capita GDP (Rp million) 1.12 1.54 1.08 1.46b 2.46 1.49

2.65 1.45

% living in poverty (1998) 43 12 27 63 8 28 16 30

Human development

index (1999) 65 67 64 58 69 64 64 64

aData in this table reflect the administrative divisions existing prior to creation of new

kabupaten and kota in 2000 and more recently (see text).

bThis figure seems suspiciously high compared with other figures in the economic

indi-cators section of this table.

Sources: Education and household data: 1995 Supas; family planning: BKKBN (Badan Koordinasi Keluarga Berencana Nasional, National Family Planning Coordination Agency) family registration data; health and transport infrastructure: BPS Sulut (1999); eco-nomic indicators and human development index: data supplied by BPS Sulawesi Utara.

ministers in the main protestant church in North Sulawesi, the GMIM, are women. A situation like this must be rare anywhere in the world.

Northern Sulawesi’s earlier educa-tional advantage has gradually been eroded, as provincial differences in education have narrowed with the cen-tral government’s rather even-handed provision of funds. School enrolment

figures from the 1999 National Socio-Economic Survey (Susenas) show the former North Sulawesi with a rate of 93.6% at ages 7–12 (the primary school ages) and of 76.7% at ages 13–15 (the lower secondary school ages). Both figures were below the national aver-age, and gave the province a ranking of 20th in primary school and 17th in lower secondary school enrolment FIGURE 3 Northern Sulawesi: Indicators of Educational Progress, 1971–95

(%)

1971 1980 1990 1995 0

40 80 120

15-24

25-34

35-44

45+

7 9 11 13 15 17 19 0

40 80 120

1971

1980

1990

1995

(a) Literacy (b) School Enrolment Rates, Ages 7–19

20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65+

0 15 30 45

1971

1980

1990

1995

20-24 25-29 30-34 35-39 40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65+

0 15 30 45

1971

1980

1990

1995

(c) Completed Senior High School, Males (d) Completed Senior High School, Females

Sources: 1971, 1980 and 1990 population censuses; 1995 Supas.

rates—a sad decline from the days when it was Indonesia’s leader in edu-cational attainment.

Nevertheless, these figures disguise crucial regional differences, which became starkly apparent with the cre-ation of the province of Gorontalo. According to the 2002 Susenas, the school enrolment ratio at ages 7–18 was 81.4% in North Sulawesi and 66.5% in Gorontalo. The former figure was above the national average, the latter the lowest for any Indonesian province. Moreover, even within the new North Sulawesi, the Minahasan heartland (including Manado and Bitung) has much higher levels of edu-cational attainment than other parts of the province (table 3).

In higher education, North Sulawesi boasts the University of Sam Ratulangi and Manado University (formerly the IKIP, or Teacher Training Institute), as well as private universities, theological seminaries and a polytechnic. In 2000, there were 16,641 full-time students enrolled at Sam Ratulangi University, and 8,354 at Manado University (BPS Sulut 2001). Recently, La Salle Univer-sity in the Philippines has opened a private university in Manado, with all teaching conducted in English and an initial intake of 300 students. This, along with the opening of an expensive new university in Tomohon (Universi-tas Sariputra), suggests that the Mina-hasa region may be developing as an important educational centre for East-ern Indonesia. However, high levels of education in a not very diversified economy encourage ‘brain drain’. This emphasises the need to develop high-tech industry to hold well educated young people in the region. Indeed, northern Sulawesi could aspire in the longer run to be at the leading edge of information technology (IT) based industry in Indonesia. But this will

require as a minimum the develop-ment of undergraduate and masters level (S1 and S2) programs in IT.

Health services throughout north-ern Sulawesi are quite good by national standards, although indica-tors such as the ratio of hospital beds to population are clearly better in Minahasa and in urban areas than else-where (table 3). Below average infant mortality rates of 48 per 1,000, com-pared with an Indonesian figure of 52 per 1,000 (CBS et al. 1998: table 9.5), are another indicator of availability of health services. And a slightly higher proportion of babies are delivered by trained health personnel in northern Sulawesi (45.7%) than in Indonesia as a whole (43.2%).

The Regional Economy

The former North Sulawesi ranked slightly below the median in per capita gross regional domestic product (GRDP) (Garcia Garcia and Soelistia-ningsih 1998: figure 2; Akita and Alis-jahbana 2002: table 2). It was, however, the most prosperous of the provinces in Sulawesi, and its economy suffered less during the crisis and has grown more rapidly in recent years than any of Indonesia’s other provinces.4

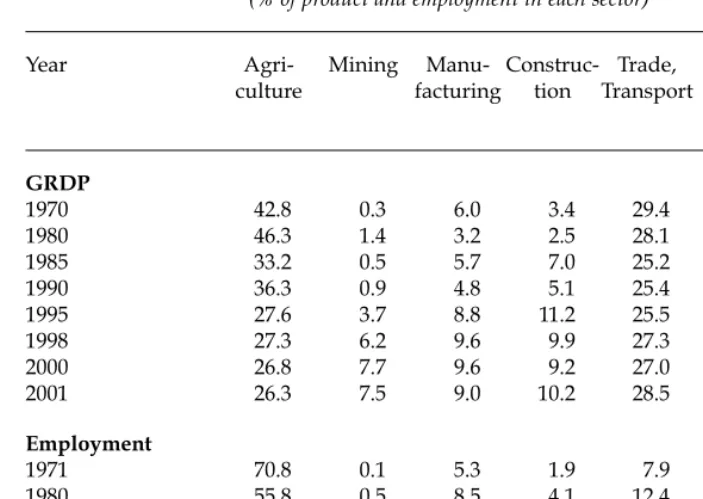

The economic structure and its changes since the early 1970s are shown in table 4. Agriculture remained dominant, though its share of GRDP declined steadily. It was mining and construction rather than manufactur-ing whose share grew significantly. The process of industrialisation has not been as dynamic as hoped; manufac-turing continues to provide less than 10% of output and employment (only one-third of the Indonesian average in the case of output and less than two-thirds in the case of employment). Over the period 1975 to 1996, the for-mer North Sulawesi’s share of national

GDP declined from 0.87% to 0.67%. The province was therefore becoming poorer relative to the national average over that period. This economic per-formance fell far short of the potential of a province well endowed with agri-cultural and marine resources and a dynamic and well educated popula-tion.

Post-crisis Economic Performance

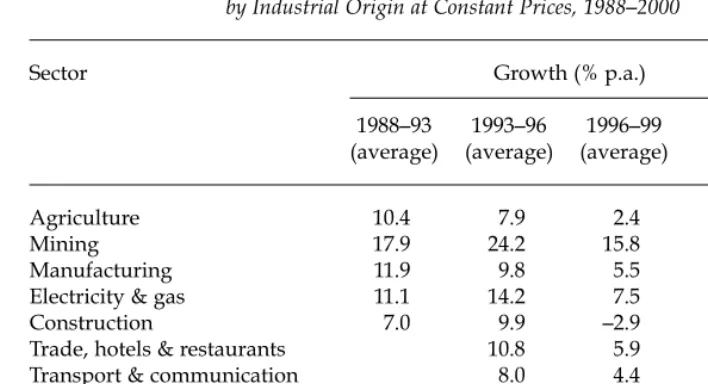

Northern Sulawesi’s economy seems, however, to have been more resilient than that of most other provinces in the face of the national economic crisis that began in 1997. The economy contracted

by 2.4% in 1998 (far less than the 14% recorded for Indonesia as a whole). The decline was caused mainly by the negative growth of construction and financial services (table 5), which had still not recovered their 1996 levels by 1999. However, the economy quickly recovered and GRDP grew at a rate of 5.8% in both 1999 and 2000, faster than GDP growth for Indonesia as a whole. This improvement was also reflected in a reduction in poverty. The inci-dence of poverty had decreased signif-icantly over time to a little below 10% in 1997, but according to official esti-mates it rose sharply to over 20% in TABLE 4 Economic Transformation of North Sulawesi–Gorontalo

(% of product and employment in each sector)

Year Agri- Mining Manu- Construc- Trade, Finance Total

culture facturing tion Transport & Services

GRDP

1970 42.8 0.3 6.0 3.4 29.4 17.7 100

1980 46.3 1.4 3.2 2.5 28.1 18.2 100

1985 33.2 0.5 5.7 7.0 25.2 27.5 100

1990 36.3 0.9 4.8 5.1 25.4 25.9 100

1995 27.6 3.7 8.8 11.2 25.5 22.7 100

1998 27.3 6.2 9.6 9.9 27.3 18.9 100

2000 26.8 7.7 9.6 9.2 27.0 19.0 100

2001 26.3 7.5 9.0 10.2 28.5 17.8 100

Employment

1971 70.8 0.1 5.3 1.9 7.9 14.1 100

1980 55.8 0.5 8.5 4.1 12.4 18.7 100

1985 57.9 0.3 7.2 4.0 14.9 16.2 100

1990 56.4 1.3 8.0 3.8 13.7 16.6 100

1995 51.2 0.8 7.3 5.1 18.0 17.7 100

2001 48.6 0.6 5.7 4.9 22.4 16.5 100

Sources: GRDP data: 1970: Regional Income Accounting Group Sulawesi Utara (1973); 1980: Kantor Statistik Propinsi Sulawesi Utara (1983); 1985: Kantor Statistik Propinsi Sulawesi Utara (1991); 1990: Bappeda Tingkat I Sulawesi Utara dan Kantor Statistik Propinsi Sulawesi Utara (1990); 1995: Bappeda Tingkat I Sulawesi Utara dan Kantor Sta-tistik Propinsi Sulawesi Utara (1996); 1998, 2000, 2001: BPS Sulawesi Utara, Sulawesi Utara dalam Angka, various years. Employment data: 1971, 1980 and 1990 population censuses; 1985 and 1995 Supas; and 2001 Sakernas.

both 1998 and 1999. A recent study shows that it then fell back to 10% in 2000 (SMERU 2002: 16).

The sharp rise in the official poverty estimates for 1998–99 seems inconsis-tent with the region’s relatively strong economic performance over the crisis period. In any event, figures for 2002 indicate that North Sulawesi, with only 11.2% of its population living in poverty, had the fourth lowest poverty incidence of any Indonesian province, whereas Gorontalo, with 32.1% living in poverty, ranked third highest in poverty incidence (BPS 2003).

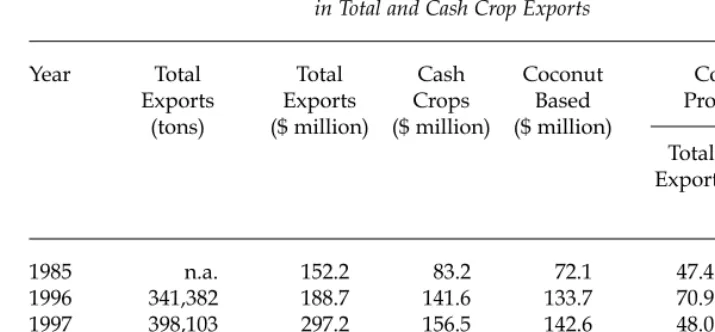

Exports increased dramatically between 1995 and 1997, almost dou-bling in dollar terms, but the rate of increase fell to less than 2% per annum in 1999 and 2000. By 2000, the total value of exports was $328 million, with the two largest components, coconut oil and canned fish, contribut-ing 52% and 6% respectively (BPS Sulut 2001).

Bank Indonesia reported a decline in investment after 1997 (Manado Post, 8/1/01). Planned domestic invest-ments fell from Rp 320 billion in 1997 to Rp 186 billion in 1998. Reported realised foreign investment dropped from $450 million in 1997 to $93 mil-lion in 1998, and declined further to $19.5 million in 1999 and $13.6 million in 2000 (www.bps.go.id).

Given the low rate of investment, how did the region achieve a more modest decline in GDP than the coun-try as a whole in 1998, and the subse-quent relatively high economic growth rate? There are three likely explana-tions. (1) The growth was based on ris-ing exports, with the rupiah depreciat-ing to 3–4 times lower than its rate in 1997, while inflation only doubled price levels over the same period. (2) The relatively peaceful environ-ment in northern Sulawesi enabled business to proceed as usual, as well as attracting unrecorded savings and TABLE 5 North Sulawesi–Gorontalo: Growth and Percentage Distribution of GRDP

by Industrial Origin at Constant Prices, 1988–2000

Sector Growth (% p.a.) Share

1999 1988–93 1993–96 1996–99 2000

(average) (average) (average)

Agriculture 10.4 7.9 2.4 6.7 26.9

Mining 17.9 24.2 15.8 13.0 7.2

Manufacturing 11.9 9.8 5.5 6.5 9.5

Electricity & gas 11.1 14.2 7.5 4.5 0.8

Construction 7.0 9.9 –2.9 3.4 9.4

Trade, hotels & restaurants 10.8 5.9 6.8 12.6

Transport & communication 8.0 4.4 4.5 14.5

Finance & business services 3.1 –16.3 4.3 3.1

Other services 8.4 2.2 3.1 16.0

Total 8.6 19.7 2.9 5.8 100.0

Sources: 1996–2000: BPS Sulut (2000): table 11.2, as corrected by the author; 1993–96: cal-culated from Brodjonegoro (2001): table 1; 1988–93: Bappenas (1998): table 7.

investment from refugees and business people moving from unstable neigh-bouring regions. (3) The recent com-pletion of the Sam Ratulangi airport extensions and the improved facilities in the port of Bitung played a role in increasing trade and tourism.

Over the period 1985–95, employ-ment in agriculture increased by some 10%, though agriculture’s share of employment declined (table 4). In 1995, those employed in agriculture worked fewer hours than those employed in any other industry, reflecting the growth of part-time work. This was true for both males and females, although in agriculture the average hours worked by females (23) were considerably lower than those worked by males (37). Agriculture con-tinued to play a vital role in the econ-omy in 1995, providing the only source of income of 39% of households, the main source of income of 10% and a partial source of income for a further 10%. Yet even in rural areas, non-agricultural activities provided the only source of income for 26% of households, and a partial source of income for a further 23%. As elsewhere in Indonesia, the employment struc-ture of rural areas has become quite complex.

The 1995 intercensal survey (Supas) shows that the monthly earnings of employees in northern Sulawesi were close to the national average: 70% earned more than Rp 100,000 per month, 36% more than Rp 200,000, and 15% more than Rp 300,000.

Unemployment remains a problem. According to the Susenas data, the unemployment rate in northern Sulawesi was above the national aver-age over the entire 1996–2002 period and, although declining somewhat, it remained around 12% in 2002 (BPS 2003). As elsewhere in Indonesia, the

rate is higher for females than for males. On the face of it, high unem-ployment seems inconsistent with high wage rates in rural areas (Rp 20,000 to 25,000 per day), and with the generally good performance of the northern Sulawesi economy. The explanation probably lies in the reluctance of high school graduates in rural areas to work in agriculture, making labour hard to find in peak periods despite the pres-ence of unemployed youth. Senior high school and tertiary graduates, who are being produced in increasing numbers, aspire to white collar employment, opportunities for which are limited (except, briefly, in Gorontalo following the creation of the new province). Only 39 of the 2,000 applicants for employment as public servants in Manado in January 2001 were accepted. It is not unusual to find graduates in northern Sulawesi who are not looking seriously for work, or who take employment such as bus driving that does not fully use their skills. Others seek opportunities fur-ther afield, in East Kalimantan, Batam or Jakarta.

Infrastructure

The development of the trans-Sulawesi highway has been an impor-tant factor in making markets work more effectively in the northern penin-sula of Sulawesi, and in reducing price variations. In the 1980s it took about 14 hours to go by bus from Manado to Gorontalo. Nowadays it takes only six hours. Before the 1990s, the poor con-dition of provincial roads made travel dangerous. These have now improved, though the condition of roads in gen-eral is not as good as in Java and some other regions, with over 50% still in quite poor condition and unsafe for travel by ordinary car. Damage to roads and bridges in heavy rain

still causes difficulties and isolates vil-lages.

The kabupaten of Minahasa is quite well served by the national and pro-vincial road network, which enables the region to make good use of its resources. Some people even believe that the sub-region has been over-exploited. Forest occupies less than 10% of Minahasa, compared to around 65% in Gorontalo and Bolaang Mon-gondow.

Sea transport plays an important role in communication in northern Sulawesi, especially in commodity trading. Bitung has grown in signifi-cance as the main international har-bour in the northern part of Eastern Indonesia. Although the quality of its facilities is far behind that of Sukarno Harbour in Makasar, it has an advan-tage in terms of depth, good protection from turbulent weather and strategic location on the Pacific rim. Upgrading has been taking place, and there has

been a significant increase in the direct trans-shipment of containers from Bitung port to Singapore and other main ports in the Pacific. Formerly, shipments went via Surabaya and Jakarta.

Sam Ratulangi Airport has been upgraded and the runway extended to take Boeing 747s carrying up to 15 tonnes of freight. Plans for further extension will enable it to take up to 60 tonnes.

MAJOR ECONOMIC SECTORS Agriculture and Fisheries

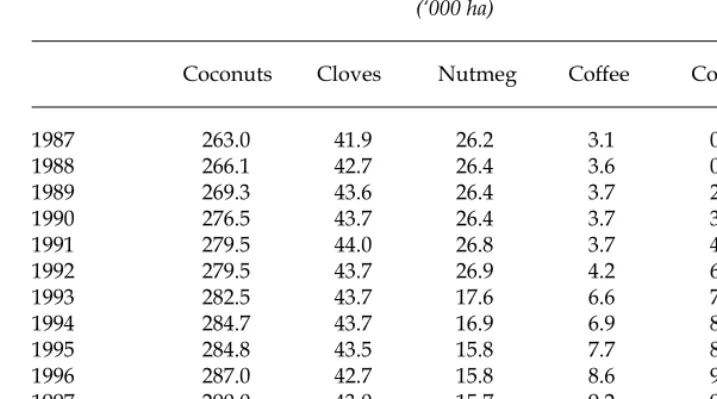

The economy of northern Sulawesi is principally agri-based (tables 4 and 5). As the backbone of the economy, pri-mary industry provides employment for approximately half of the total labour force, and contributes around a quarter of total income and 90% of total exports (about $300 million, or Rp 2.1 trillion). Increased agricultural TABLE 6 Area under Different Plantation Crops in North Sulawesi–Gorontalo, 1987–99

(‘000 ha)

Coconuts Cloves Nutmeg Coffee Cocoa Vanilla

1987 263.0 41.9 26.2 3.1 0.8 1.4

1988 266.1 42.7 26.4 3.6 0.9 2.0

1989 269.3 43.6 26.4 3.7 2.0 2.3

1990 276.5 43.7 26.4 3.7 3.0 2.5

1991 279.5 44.0 26.8 3.7 4.1 2.6

1992 279.5 43.7 26.9 4.2 6.3 3.8

1993 282.5 43.7 17.6 6.6 7.4 4.0

1994 284.7 43.7 16.9 6.9 8.6 4.7

1995 284.8 43.5 15.8 7.7 8.7 5.3

1996 287.0 42.7 15.8 8.6 9.1 5.3

1997 290.0 43.0 15.7 9.2 9.2 5.3

1998 296.0 43.0 17.0 9.2 9.4 5.4

1999 301.1 43.0 17.0 9.3 10.2 5.5

2000 317.2 43.4 17.0 9.4 10.9 5.6

Source: BPS Sulawesi Utara, Sulawesi Utara dalam Angka, various years.

productivity is therefore essential to speeding up the post-crisis economic recovery program.

Northern Sulawesi has a strong comparative advantage in interna-tional trade in copra, nutmeg, vanilla, cloves, fish and horticulture. Agricul-ture is dominated by plantation crops (especially coconuts, cloves, nutmeg, coffee and recently vanilla and cacao), though there are also food crops (espe-cially corn and rice). The total area of plantations is more than 400,000 ha, three-quarters of it devoted to coco-nuts (table 6). In fact about 60% of farmers in northern Sulawesi are coconut farmers, and around 90% of cash crop based exports are coconut products: coconut oil, desiccated coconut, and coconut meal (table 7). The role of other crops is also impor-tant. Northern Sulawesi produces one-fifth of Indonesia’s total output of cloves and two-thirds of its nutmeg; it also produces the best quality vanilla. However, the marketing of some of these products, and certainly the

deter-mination of commodity prices, has been beyond the control of northern Sulawesi producers.

The Coconut Industry. The coconut industry dominates northern Sula-wesi’s employment, agricultural pro-duction and exports. The area planted to coconuts could still be increased if prices warranted it. According to Litow (2000), 660,000 ha of land in northern Sulawesi is considered suit-able for coconut plantations, more than twice the area now under coconuts (table 6). Most coconut farms are small: 60% of them grow coconuts on only 0.2–5 ha. Owing to the predominance of old trees and to poor farm manage-ment, productivity is far less than the potential 3 tons per ha. Approximately 123,000 ha of coconut palms (30% of the total stock) are more than 60 years old (Litow 2000). Appropriate replant-ing or rejuvenation programs appear to be needed, though rejuvenation pro-grams in operation since the 1970s have had limited impact. Productivity could be increased, at least in theory, TABLE 7 North Sulawesi–Gorontalo: Role of Coconut Based Products

in Total and Cash Crop Exports

Year Total Total Cash Coconut Coconut Based

Exports Exports Crops Based Products as % of:

(tons) ($ million) ($ million) ($ million)

Total Total Cash Exports Crop Based

Exports

1985 n.a. 152.2 83.2 72.1 47.4 86.7

1996 341,382 188.7 141.6 133.7 70.9 94.4

1997 398,103 297.2 156.5 142.6 48.0 91.2

1998 482,672 317.7 128.1 114.2 35.9 89.1

1999 403,944 323.4 154.2 145.8 45.1 94.6

2000 505,744 328.1 n.a. 126.7 38.6 n.a.

Source: Dinas Perindustrian dan Perdagangan Propinsi Sulawesi Utara (North Sulawesi Industry and Trade Service).

from the existing 1.1 tons per ha to 2.6–3.3 tons per ha by improving farm management and fertiliser use (Allore-rung 2000).

The main constraint on increasing coconut production is the volatility of copra prices. They were Rp 4,000 per kg in 1999, but plummeted to Rp 1,200 in June 2000 and remained at Rp 1,100 in April 2001, rising again to an aver-age of around Rp 1,700 per kg in 2002–03. The longer-term trend of gradual decline in copra prices has apparently been caused by coconut oil’s image as a cholesterol-rich edible oil.

Before 1990, the marketing of copra was excessively regulated under the copra marketing board (Badan Pen-gelola Kopra, Bapengko), in order to ensure that the copra needs of Java were met. In 1990, the government deregulated the marketing system. Nevertheless, the market continues to be strongly influenced by a few coconut oil companies (e.g. Bimoli and Inimexintra), which have traditionally controlled the buying of copra from farmers by providing ‘advance pay-ments’. More recently, the government has tried to respond to the low prices by encouraging farmers to set up a coconut farmers association, Apeksu (Asosiasi Petani Kelapa Sulawesi Utara). Apeksu has blamed PT Bimoli, the largest copra buyer, for applying low monopsony prices. Bimoli coun-ters that it can do nothing to increase copra prices, whose level is due to the deterioration of commodity prices in the world market.

With an average ownership of 1.5 ha per farm household, a coconut farm family cannot earn sufficient income to meet its basic needs. Even if copra achieved a price of Rp 4,000 per kg, a coconut farm with an average pro-duction of 1.1 tons would yield a

net income of only Rp 2.5 million (assuming harvesting costs of 40% of income)—below the absolute rural poverty line for the region, which was over Rp 3 million per family per year in 2001. The coconut farmers are sur-viving by planting land under coconut trees with food crops, and by seeking employment elsewhere, for example, in small-scale gold mining (which may yield an income of Rp 150,000 per day). The role of coconuts as the main income source of the majority of north-ern Sulawesi’s people demands seri-ous government effort to ensure that incomes of coconut-producing house-holds are adequate, either through pro-ductivity measures, or through helping coconut growers gain access to other sources of income, or both. The stan-dard approach to increasing produc-tivity is to apply fertiliser, improve farm management and undertake re-planting. In the long run the industry must make the best use of the 220,000 ha of uncultivated land under the existing coconut palms (Litow 2000), and diversify the range of coconut products to include coconut meal, coconut fibre, desiccated coconuts, fresh coconut juice, coconut milk, detergent, concentrated coco milk, dis-tilled glycerine, disdis-tilled fatty acid, charcoal and carbon fibre. It cannot survive the low copra prices if it relies only on copra and crude coconut oil (Sondakh 2000a). The main barriers to diversification have been high trans-port costs and ineffective application of agro-industrial technology.

The present targets of the North Sulawesi government are to rejuvenate 41,000 ha, plant new palms on about 31,000 ha, increase farm productivity to 1.5 ton per ha by 2005, and increase intercropping with cocoa (22,000 ha), vanilla (5,000 ha), coffee (2,500 ha), fruit (2,500 ha) and food crops 45,000 ha).

Productivity will be increased through better drainage and application of fer-tiliser.

The Clove Industry. Cloves are the second most important agricultural product in northern Sulawesi. The area planted in recent years was 43,000 ha, of which 20,000 ha was in good condi-tion, 15,000 ha in poor condition and 8,000 ha in very poor condition. Native to the neighbouring Moluccan Islands, cloves have long been grown in north-ern Sulawesi, mainly on the slopes of the Minahasa region. Even the posses-sion of a few trees can mean important cash income for a family. Prior to ‘great harvests’ (which occur every fourth year between more normal annual har-vests), consumer goods flood into vil-lages, supplied by traders as advance payments for specific quantities of dried cloves. The cloves are exported to Java, largely to be used in scented

kretek cigarettes, which contain as much as 50% clove powder by weight. Production per hectare in peak harvest years ranges from 500 to 800 kg, depending on the variety of clove and fertility of soils.

Since 1970, clove marketing has attracted serious attention from the central government. At least three main systems have been applied: first, the partially regulated pre-1991 mar-keting system, which granted roles to farmers’ cooperatives in the collection and marketing of cloves; second, the over-regulated marketing system under BPPC (Badan Penyanggah dan Pemasaran Cengkeh, the Clove Buffer-stock and Marketing System) from 1991 to 1999; and third, the current ‘free trade’ marketing system.

During the 1970s, farmers enjoyed high clove prices owing to rising demand for kretek cigarettes and a lim-ited supply of cloves. High prices encouraged the import of cloves from

Malagasy and the expansion of clove-growing areas, until supply began to exceed domestic demand in the late 1980s. In the 1970s, clove farmers sold to small traders, who sold to inter-island traders, who in turn sold to

kretek manufacturers in Java. In 1976, the government encouraged village cooperatives to collect cloves from farmers, but shortage of capital limited their role. The inter-island traders, closely linked to the kretek manufactur-ers, played the dominant role in clove gathering as well as in pricing. Ijon

(advance payment) was common, and this depressed farmgate prices.

In 1980, Presidential Decision No. 8/1980 granted a bigger role to village cooperatives (Koperasi Unit Desa, KUD) in clove collection and distribu-tion from farmers to kretekfactories via inter-island traders. Between then and 1990, clove farmers were required to sell their output through KUD to inter-island traders at or above the floor price of Rp 6,500 per kg. In reality, the proportion of cloves sold by farmers through KUD was only about 4% in Maluku (Godoy and Bennett 1990) and about one-third in North Sulawesi. Prices paid by KUD were frequently below farmgate prices, and the KUD and domestic agents did not have the financial resources to support the floor price. The marketing system was rela-tively competitive, with inter-island traders being the main buyers in the clove producing centres, and also transporting the cloves to Java.

This phenomenon attracted the attention of Tommy Soeharto (the son of former President Soeharto), who entered the clove business to capture the benefits enjoyed by the traders and clove manufacturers. This rent seeking activity underlay the establishment of BPPC in 1991 (Sondakh 1999). BPPC was granted a ‘very soft loan’ of about

$350 million to act as the sole market-ing agent, collectmarket-ing cloves from farm-ers via KUD and their Puskud (Pusat Koperasi Unit Desa, village coopera-tive centres), and selling them on to the

kretek manufacturers. The stated rationale for this decision was that the practice of ijonwas prevalent and clove traders were exploiting producers. Consumer and producer surpluses were transferred from the kretek facto-ries and clove producers to the market-ing agents imposed by the state: BPPC, KUD, Puskud, Inkud (Induk Koperasi Unit Desa, the Central Village Cooper-ative Board of Management), Suco-findo (Superintending Company of Indonesia, a state enterprise in charge of quality control) and the govern-ment, in the last case in the form of SRC (Sumbangan Rehabilitasi Ceng-keh, the Clove Rehabilitation Fund). The BPPC period from 1992 to 1997 was a disastrous one for the clove industry, because BPPC bought at only Rp 4,000 per kg, far below the world price of Rp 13,500 and the kretek manu-facturers’ prices. Significant declines in area, production and productivity resulted.5The average ‘peak year’ pro-duction of 20,000 tons per year fell to below 8,000 tons in 1999 (a peak year). Clove producers were exploited in an additional way during this period. Before its disappearance in 1998, Inkud retained the so-called ‘dana SWKP’ (sumbangan wajib kepada petani, an obligatory payment to the farmer) of Rp 1,900 per kg. The funds were sup-posed to be returned to the farmers in cash. The SWKP for North Sulawesi amounted to about Rp 200 billion over five years, of which Rp 150 billion was supposed to be returned to the province. It remains unclear whether these funds are still in accounts associ-ated with the now abolished BPPC, or have vanished due to corruption. What

is clear is that the farmers who are enti-tled to receive reimbursement are never likely to see these funds.

One of the main undertakings the government made in its January 1998 Memorandum of Understanding with the IMF was to deregulate the clove marketing system. This has been done, government intervention has ceased, and restrictions on imports have been removed. Farmgate prices rose dra-matically after BPPC was abolished, from Rp 4,000 per kg in 1998 to Rp 90,000 in late 2001. In response, the government and farmers began replanting and rehabilitation of clove trees in poor condition. However, prices gradually fell during 2002, set-tling at a figure of around Rp 25,000 from June 2002 to mid 2003. This is still well above the break-even point for profitability of clove monoculture— about Rp 17,000 (Dumais et al. 2002).

Other Plantation Crops. Nutmeg is another important tree crop in north-ern Sulawesi. A sourish fruit that grows on tall trees, its hard kernel pro-duces nutmeg (biji pala), while the beautiful lacey vermilion surrounding it is dried and ground to become mace (fulli). Candien, the nutmeg fruit, is a pleasant treat and has been exported to Java as a snack food. The main issue facing the nutmeg industry is that even as the world’s main nutmeg producer, supplying 70% of world demand, northern Sulawesi has not been suc-cessful in determining nutmeg prices, apparently because there is no effective nutmeg producers’ association to influence production and sales (Marks 2002).

Vanilla production grew rapidly during 1990–97, replacing cloves, but difficulties were encountered in man-aging quality, high prices causing farmers to harvest too early. Exports of vanilla amounted to 30 million tons in

1997, 66 million tons in 1998 and 41 million tons up to October 1999, with a value of $1.08 million, $1.46 million and $0.85 million respectively (Deper-indag Sulut 2000).

As for coffee and cocoa, both have good potential, and cocoa could be intercropped under coconuts. There is a strong domestic demand for both cof-fee and cocoa, and a tradition of cofcof-fee production and export to Europe. Since the late 1980s, production of both crops has increased sharply, indeed spectacu-larly in the case of cocoa (table 6).

Food Crops. Corn and rice are the main food crops produced in northern Sulawesi, well known as one of Indo-nesia’s main corn-producing regions. Traditionally corn had been the main staple food, but nowadays it is a sub-stitute for rice. Approximately 35,000 ha is suitable for wet rice cultivation, and most of this can be cultivated twice a year, resulting in production of over 62,000 ha of irrigated rice per annum; a further 21,000 ha of rice is produced each year on rainfed land (BPS Sulut 2001). The area suitable for other food crops, mostly ‘dry land’ (lahan kering), is about 500,000 ha, over 80% of which is presently in use.

Northern Sulawesi is self-sufficient in rice, because of increased productiv-ity per hectare in recent times, as has also occurred in many other food crops. With a population of over 2.8 million in 2000, and per capita rice consumption of 120 kg, the province needs approximately 340,000 tons of rice per annum. In both 1999 and 2000, production exceeded this figure (BPS Sulut 2000, 2001). Other food crops worth noting are soybeans, groundnut, mungbeans, cassava, vegetables and fruit. There is potential to export pota-toes, other vegetables, pineapples and flowers, but this would require better post-harvest technology.

Livestock. Livestock production is mainly on a small scale. Its share in GRDP is therefore relatively low, only 2.8% of the 26% share of primary industry in GRDP in 2001. About 30,000 head of cattle out of a total cat-tle population of 280,000 are exported per annum, but there is a danger that this rate may decline owing to the sale of heifers. Horse raising is becoming a more important industry in Minahasa. Breeding is targeted to supply domes-tic demand, especially in Jakarta. The new North Sulawesi is one of the few provinces in Indonesia that raises pigs. Availability of feed, especially copra meal, corn and fish meal, provides good potential for increasing pig pro-duction. However, poor agri-business infrastructure, a limited local market and high transport costs may prevent this potential from being realised.

Fisheries. The fishing grounds of northern Sulawesi are a small but important part of the larger fishing grounds of Indonesia’s ZEE (exclusive economic zone) territory, used by fleets based in the fishing ports of Gen-eral Santos (the Philippines), Ambon and Ternate (no longer operating owing to internal conflict in the region), Benoa, Biak and Bitung. It is estimated that the capacity of Indone-sian fishing vessels is only about 30% of the total capacity of fishing vessels exceeding 20 gross tonnes operating in Indonesian waters (personal commu-nication, Mr. Richard Solarngs, Chair, Himpunan Nelayan Seluruh Indone-sia, or Indonesian Fishermen’s Organi-sation, Manado). The other 70% are foreign vessels, some of them operat-ing legally and some illegally. Illegal ‘super pulseiner’ and longline fishing vessels owned by Philippine interests (but flying Indonesian flags and giving the impression they are Indonesian owned) have been catching millions of

tons of fish each year in Indonesia’s fishing grounds.

Northern Sulawesi’s fishing terri-tory has recently been divided into three areas, based on distance from the coastline: the 2–4 mile, 5–12 mile and beyond 12 mile areas, the latter includ-ing the ZEE areas. These are under the jurisdiction of the kabupaten/kota gov-ernments, the provincial government, and the national government, respec-tively. Unfortunately, there is a built-in conflict between different levels of government here. Foreign boats fish-ing in Indonesian territory have to pay a tax of 2.5% of the price of the catch. The payment goes to the central gov-ernment in the case of boats exceeding 30 gross tons, and to the provincial government in the case of smaller boats. The central government has been content with the income derived from licensing large foreign-owned boats operating beyond the 12-mile limit (which also gives the officials involved considerable opportunity for corruption), even though these vessels are seriously affecting the local fishing industry. The government of the new North Sulawesi has recently proposed to the central government the decen-tralisation of the authority to issue licences and permits for fishing in Indonesian territory, or at the very least, to raise the size limit of boats licensed by the province to 60 gross tons.

The fisheries service of the former North Sulawesi estimated the prov-ince’s fisheries potential in 2000 to be approximately 322,800 tons annually, consisting of 125,900 tons in the 2–4 and 5–12 mile areas and 196,900 tons in the ZEE areas (Kaunang 2000). From 1994 to 1998 (excluding illegal and for-eign catches), the subsector produced around 120,000 tons annually, and this increased to almost 200,000 tons in

1999, with sea fishing contributing over 90% of the yield. The increase was caused by a rise of nearly 10% per annum in the number of fishing ves-sels, from 26,777 in 1994 to 42,947 in 1999 (BPS Sulut 2001: 171).

Fish production in northern Sulawesi comes mainly from vessels based in Bitung, and a little over 30% is exported live, fresh, iced or smoked. Fish exports were about 70,000 tons in 1999 and 2000, valued at $63–65 mil-lion, around 16% of the total value of former North Sulawesi’s exports in those years. The province’s competi-tive weakness relacompeti-tive to General San-tos in the Philippines and to Taiwan, Korea and Japan, whose fleets domi-nate Indonesia’s fishing grounds, pre-vents it from reaching its production and export potential.

Northern Sulawesi has lagged behind neighbouring regions of the Philippines in making the best use of its fisheries potential. With the assis-tance of USAID and JICA (the Japan International Cooperation Agency), the government of the Philippines has successfully established General San-tos as a leading fishing port, landing about 300 metric tonnes of fish every day, the second largest total daily fish landing in the Philippines. The new North Sulawesi provincial government has proposed the building of a similar fishing port. It is expected that the completion of the project in the next few years will increase the ability of the province to make better use of its fisheries potential.

Summary. The primary industry sec-tor in northern Sulawesi has a number of areas of high potential, and every effort should be made to develop them further. The basic problem, however, is that most primary producers rely on the coconut industry, which has a lim-ited potential to yield satisfactory

incomes. Overall, agriculture is unlikely to be the main engine of growth in the future. The longer-term strategy must therefore focus on the sectors with the potential to expand more rapidly, provide higher incomes and absorb workers from the coconut industry in particular. Mining, trans-portation, tourism and services have been the best performing sectors over the past decade, though for different reasons none of them can be relied on for steady long-term growth.

Mining

As shown in table 5, mining’s rapid growth from the late 1980s made it an important contributor to northern Sulawesi’s economy. The area is quite rich in geothermal energy (with a potential of 640 megawatts per annum) and minerals, especially gold and cop-per; there are also some valuable mar-ble and granite quarrying areas. Min-ing has increased considerably in importance in recent years, with the opening in 1996 of the gold mining venture of PT Newmont Minahasa Raya in Ratatotok, whose initial pro-duction was about 12 tons per year, worth about Rp 600 billion. There are six other licensed mining activities. Small-scale gold diggings can also be found in many places, for example the hilly areas surrounding the Dumoga Valley, and in parts of Minahasa and Sangir Talaud. There are about 5,500 ‘gold extracting units’ (tromol) employ-ing about 13,000 labourers all over northern Sulawesi. One estimate puts the number of illegal miners in the region at 22,000, of whom 1,500 were working at Australian mining com-pany Aurora Gold’s Talawaan conces-sion.

Illegal miners are a threat to licensed mining interests, some of which have been forced to cease or not begin

pro-duction because of occupation of their concessions. The illegal gold miners do not pay royalties to government, and cause serious environmental damage. The Department of Mining in the for-mer North Sulawesi province esti-mated that illegal miners had poured 300–600 tonnes of mercury into the environment (400–800 kg per day) since illegal mining became wide-spread in the late 1990s, contaminating the environment and creating serious health problems. Samples from the Talawaan River show mercury levels 70 times higher than the internation-ally accepted limit for drinking water (McBeth 2000).

Both of the large gold mining ven-tures—Newmont (production) and Aurora Gold (prospecting)—faced dif-ficulties in relations with different lev-els of government, and these illustrate some of the problems of regional autonomy. Newmont’s contract with Jakarta exempted it from paying taxes on ‘overburden’ materials (waste rock or soil removed to access mineral deposits), but the head of Minahasa district assessed Newmont under a local tax code related to the sale of these materials as owing more than $8 million in back taxes (Wall Street Jour-nal, 11/4/02). The North Sulawesi provincial government is also not encouraging mining, largely for envi-ronmental reasons. Facing contract conditions in relation to disposal of tailings, the problem of illegal miners and, it is rumoured, lower than expected gold reserves, both compa-nies have now pulled out of the province.

Manufacturing and Agro-industry

The manufacturing sector has been the major disappointment in recent macro-economic performance. The small local market, the difficulty of competing in

export markets, and the general eco-nomic malaise facing Indonesia since 1997 have combined to hinder invest-ment and prevent any major new man-ufacturing activities. Manman-ufacturing has therefore failed to provide an ‘engine of growth’.

Agro-industry has made little progress. Most export products from northern Sulawesi are unprocessed: coconuts in the form of crude coconut oil, nutmeg in the form of fulli, clove in the form of dried cloves, vanilla in the form of dried vanilla, fish in the form of canned fish. If such products could be processed to intermediate or advanced states, export receipts could be doubled (Sondakh 1999). A program of agro-industrialisation would allow the receipts from tuna to be increased from Rp 10,000 to Rp 50,000 per kg. Similarly, copra, which now fetches Rp 1,200 per kg, could be exported in the form of refined edible oil and other processed products (such as desiccated coconut) for Rp 15,000 per kg. Factors constraining the further processing of coconuts and copra include high trans-port costs to world markets and low economies of scale owing to the pre-dominance of small producers.

Tourism

The importance of tourism to the northern Sulawesi economy (parti-cularly the new North Sulawesi province) was increasing steadily up to the beginning of the economic crisis in 1997. Its growth has slowed since then, although thanks to increasing interna-tional flights to Manado and the repu-tation of northern Sulawesi as a ‘safe’ region, it has not been as badly hit as most provinces.6 Promotional efforts have been continuing in countries such as Taiwan and the US. In late 2002, Manado was being served by Silk Air from Singapore four times a week,

Philippine Airlines once a week (to Davao and Manila), Bouraq Indonesia Airlines once a week (to Davao), and daily Garuda services linking Jakarta, Manado and Taipei.

Tourism to northern Sulawesi is based mainly on the region’s natural attractions. The area is rich in scenic landscapes and seascapes, and ‘has the potential to develop a unique set of quality, sustainable and diverse tourism sites throughout the Province which would spread the economic con-tribution of tourism beyond the islands and the Manado area’ (PATA Task Force 2000: 12). The diving location at Bunaken National Marine Park near Manado is world famous, but concern about its carrying capacity has led to a recommendation that further expan-sion of diving-oriented resorts along the coast of Manado should be avoided (PATA Task Force 2000). North Sula-wesi’s imposition in March 2001 of a Rp 150,000 annual entrance fee to the marine park (or Rp 50,000 per day for one or two day visits), used for envi-ronmental protection and village development in the park, has won international commendation from groups such as the Worldwide Fund for Nature. Nature-based themes appear to be the appropriate basis for future tourism strategies.

KAPET AND BIMP–EAGA

In 1996, President Soeharto called for the establishment of 13 integrated eco-nomic development zones (Kawasan Pengembangan Ekonomi Terpadu, Kapet) throughout Indonesia. The cor-ridor from Manado to Bitung was one of them, and was seen as a key locus for developmental activities in Eastern Indonesia. Its management is directly under the president, with the assis-tance of a steering committee.

The establishment of a Kapet is based on the idea that backward areas with good growth potential can have their growth accelerated by improved infrastructure, provision of market access and introduction of incentive policies designed to bolster investment and trade. Through flow-on effects, the Kapet is expected to boost economic growth in its entire region. Meeting the preconditions for growth should enable the area to attract investment, and transform the economic structure into one with an industrial orientation (Sondakh 2000b). It is further expected that the establishment of a Kapet will promote tourism, develop agro-industry, raise the export of finished products, and spur the growth of the financial services and other sectors through forward and backward link-ages. At the same time, there is the danger that the Kapet will serve to exacerbate centre–periphery inequali-ties within the region.

Thanks to its international-level air-port and air-port, high population density and good levels of education, the Manado–Bitung zone very satisfacto-rily meets the requirements of a Kapet area (PT Soilex Sulut Sejati 1999). This zone has long been designated the key export centre and industrial zone for the region. The central government aims to develop the port of Bitung into an international hub port by 2010. On 16 July 2001 President Abdurrahman Wahid inaugurated the upgrading of Bitung port and opened the upgraded Sam Ratulangi airport. Kapet Manado– Bitung, under the chairmanship of North Sulawesi’s governor, has been given a national mission to develop the surrounding area further through investment in infrastructure and trial zones, and to issue one-stop indus-trial permits to increase private invest-ment in many aspects of developinvest-ment.

Another regional program with a capacity to influence the development of northern Sulawesi is the BIMP– EAGA (ADB 1996). This is a regional economic cooperation scheme involv-ing Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines (BIMP) in the East ASEAN Growth Area (EAGA). Origi-nally, the Indonesian provinces included in this scheme were East Kali-mantan, West Kalimantan and the for-mer province of North Sulawesi. In 1996, seven more provinces were added. This program does not appear greatly to have affected developments in northern Sulawesi, though through visits and activities under the program it has linked the region a little more closely to nearby Mindanao in the Philippines and Sabah in Malaysia.

MEETING THE CHALLENGES OF REGIONAL AUTONOMY

The creation of the new province of Gorontalo, and of several new kabu-paten and kota, occurred just at the time that regional autonomy was intro-duced in Indonesia. The new province and districts therefore faced a double challenge. Absence of volcanic soils and frequent flooding restricts agricul-tural productivity in kabupaten Goron-talo, though the smaller population in

kabupaten Boalemo is more prosperous because it is concentrated in the rich Randangan River basin. The govern-ment of the new province plans to boost local corn and fish production, which are the two economic main-stays, and to develop the agri-business side of the corn industry. It is also seek-ing central government fundseek-ing to lengthen the airstrip of Gorontalo’s Jalaluddin airport and improve the two small seaports. Nevertheless, it is hard to envisage much potential for manufacturing in the province, or a

lessening of the need for it to rely heav-ily on the airport, port and other infra-structure of neighbouring North Sula-wesi province.

Regional autonomy has brought with it many new challenges for devel-opment planning. Whereas formerly the regional planning office (Bappeda) submitted its development plan to Jakarta, and the province essentially had to live with the decisions taken there, now the plans made by the tech-nocrats at the provincial level have to face two hurdles in implementation: the political process of clearing the plan through the provincial assembly (DPRD), where party politics and per-sonal interests tend to take precedence, and the greater authority of the

kabupaten–kota level in implementa-tion. An example of the kinds of issues faced is provided by the reclamation of the Manado waterfront. Comparable on a smaller scale with waterfront land reclamation in Manila and Singapore, this has provided centrally located land that is of considerable value for commercial development, and also has great potential to provide much needed park space facing the sea. However, the provincial government’s aim to reserve some of the land for such public uses has met resistance from the municipality, which seeks to maximise its rental returns.

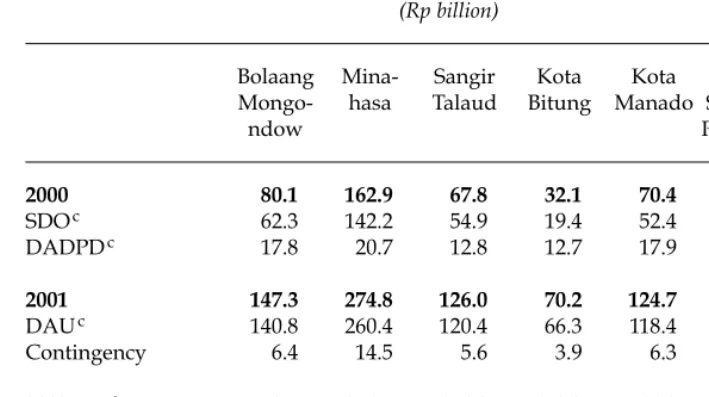

THE IMPACT OF LAW 25/1999 ON THE REGIONAL FINANCE OF NORTHERN SULAWESI

The reform era in Indonesia has been marked by administrative and finan-cial changes in relations between the central government and the regions, as set out in Law 22/1999 (on regional administration) and Law 25/1999 (on fiscal decentralisation), both imple-mented in 2001. Law 22 grants the

provinces, kabupaten and kota auton-omy in electing their local govern-ments, making their own regional development plans and managing most of their affairs. Law 25 provides a new formula for the sharing of rev-enues between the centre and the regions (table 8), the replacement of the former SDO (sumbangan daerah otonom, autonomous region subsidies) with DAU (dana alokasi umum, or general purpose funds), and permission for local governments to raise foreign loans. The sectoral budgets formerly reaching local governments through the regional offices (kanwil) of central government departments are now paid as ‘deconcentrated funds’ to the office of the corresponding sectoral agency (dinas) responsible to the provincial governor (for more details, see McLeod 2000: 33–7; Lewis 2003). The goal is the decentralisation of responsi-bility for a broad range of functions.

The major problem is that the fiscal capacity of local governments varies according to resource endowments, economic structure and stage of eco-nomic growth. The new law benefits areas rich in natural resources, espe-cially the oil and gas producing regions (Riau, Aceh, East Kalimantan and Irian Jaya), and also Jakarta. Poor districts will suffer because their ‘own-source revenues’ (PAD, pendapatan asli daerah) from local taxes and user fees (retribusi) cannot match the local expenditure needed to finance the tra-ditional routine and development budget. Typically, PAD contribute only 4–15% of regional budgets; the gap is filled by central budget allocations in the form of ‘routine’ and ‘develop-ment’ funds in the New Order era, and DAU, DAK (dana alokasi khusus, special purpose funds) and foreign loans under the new law. There are only five provinces whose ‘fiscal potential’ from

own-source revenues exceeds fiscal needs.

Is northern Sulawesi worse off or better off under the new law? Accord-ing to the initial formula used, kabu-paten and kota fared better and provinces worse (table 8). This was the result of less DAU funding being allo-cated to the province and more to the

kabupaten and kota. All kabupaten and

kota show significant increases in their budgets in nominal terms. Under the new law, the provincial government of the new North Sulawesi received only Rp 76 billion of DAU, compared to esti-mated fiscal needs of around Rp 230 billion (Mailangkay 2001). This was exacerbated by the limited size of the

development budget, only Rp 8 billion, down from Rp 68 billion in 1998/99 and nearly Rp 90 billion in 1999/2000. As a result, the province faced a real problem in meeting fiscal needs, espe-cially the wages and salaries of provin-cial public servants who had not been transferred to the kabupaten/kota level or to the new province of Gorontalo. There are about 16,000 public servants at the provincial level in North Sulawesi, compared to not more than 5,000 in Gorontalo. The annual DAU of only Rp 75 billion allocated to the province was clearly not enough to pay about Rp 11 billion in salaries per month.

The problem was simply caused by the formula for distribution of DAU TABLE 8 Changes in Central Government Allocations to Provincial and District Budgets

in the Current Province of North Sulawesi, 2000–02a

(Rp billion)

Bolaang Mina- Sangir Kota Kota North Total Mongo- hasa Talaud Bitung Manado Sulawesi

ndow Provinceb

2000 80.1 162.9 67.8 32.1 70.4 114.2 527.3

SDOc 62.3 142.2 54.9 19.4 52.4 34.5 365.8

DADPDc 17.8 20.7 12.8 12.7 17.9 79.6 161.5

2001 147.3 274.8 126.0 70.2 124.7 220.5 963.4

DAUc 140.8 260.4 120.4 66.3 118.4 75.6 781.9

Contingency 6.4 14.5 5.6 3.9 6.3 144.9 181.5

2002 total 178.7 316.7 156.0 110.2 144.2 233.5 1139.3

% change 2000–2001 83.9 68.9 85.8 118.7 77.1 93.1 82.7

% change 2001–2002 21.4 15.2 23.8 57.0 15.7 5.8 18.3

aSee table 3, note a.

bProvincial level budget.

cSDO: sumbangan daerah otonom (autonomous regions subsidy); DADPD: daftar alokasi dana

pembangunan daerah (regional development fund allocation); DAU: dana alokasi umum (general purpose funds).

Source: Data supplied by Bappeda Sulawesi Utara (North Sulawesi Development Plan-ning Board).