Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 17 January 2016, At: 23:14

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

INFRASTRUCTURE POLICY IN INDONESIA,

1965–2015: A SURVEY

Peter McCawley

To cite this article: Peter McCawley (2015) INFRASTRUCTURE POLICY IN INDONESIA, 1965–2015: A SURVEY, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 51:2, 263-285, DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2015.1061916

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2015.1061916

Published online: 24 Aug 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 195

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/15/000263-23 © 2015 Indonesia Project ANU http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2015.1061916

Fifty Years of

BIES

INFRASTRUCTURE POLICY IN

INDONESIA, 1965–2015: A SURVEY

Peter McCawley

The Australian National University

This survey, irst, provides an overview of the main developments in the infrastruc

-ture sector in Indonesia during the past ive decades and, second, considers what the main policy and management bottlenecks in infrastructure appear to be. The over

-view of main developments indicates that, in broad terms, most parts of the sector have expanded considerably but that the needs remain acute for further expansion

and for attention to the maintenance of existing facilities. Demand for infrastructure is high, especially since the regulated prices set for infrastructure services are often

low. Access is often dificult, however, because of shortages of infrastructure, and quality is often unsatisfactory because of poor maintenance and indifferent man

-agement. These problems of access are exacerbated by the regulation of prices. This overview also points to the markedly different performances of industries in which pro-competitive policies have been applied and those in which more traditional policies of close regulation have restricted the operation of markets.

Keywords: infrastructure, regulation, law, prices, markets, land, inance JEL classiication: L51, L90, L97, L98

INTRODUCTION

Infrastructure plans and policies in Indonesia are a bewildering kaleidoscope of promises, underfulillment, delays, and outright cancellations. The various indus -tries (transport, power, water, telecommunications, and so on) within the sector

operate largely as silos, with little coordination between them; central, provincial, and district governments house a myriad of policymakers and regulatory agen

-cies; and, because engineers and oficials who believe in planning tend to domi

-nate policy-making circles, economic principles are often brushed aside in the

design of infrastructure policy.

This survey of infrastructure policy in Indonesia will draw in particular on

relevant material published in the Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies (BIES)

since its irst issue, in 1965. It will cover the main developments in the sector dur

-ing the past 50 years and discuss the main policy and management bottlenecks holding back growth in infrastructure in Indonesia. Two matters need to be noted

at the outset. First, infrastructure policy is currently a top concern for economic

policymakers—ministers and oficials alike—in Jakarta. President Joko Widodo, in his irst few months in ofice, announced major proposals for the infrastruc

-ture sector: he abruptly cancelled tentative but long-standing plans to build the large ($20 billion) Sunda Strait Bridge; he unveiled a number of projects to expand ports across Indonesia, consistent with his emphasis on the country’s maritime development; and he said he planned to add 30,000 megawatts of capacity to the generation industry. A range of other projects in other industries have been put

forward in recent months.

These announcements have raised expectations for a burst of activity in the

Indonesian infrastructure sector, while other events in the region have empha-sised the need to pay closer attention to infrastructure in developing countries

in Asia. The imminent establishment of China’s multilateral Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, for example, has attracted strong international interest.

Second, few of the main issues in infrastructure policy that attract widespread

comment today are new. The basic problems were discussed in early issues of BIES, in its Survey of Recent Developments series. Yet it is striking how little pro

-gress has been made over the last 50 years in tackling these problems; the actual development of infrastructure has been signiicant yet insuficient.

FRAMEWORK

Infrastructure policy is complex. Senior policymakers in government need to avoid becoming too closely involved in the details of management; they should concentrate mainly on designing the overall frameworks for policy in each indus

-try. Perhaps the key challenge in inding the balance between these two consid

-erations is to design effective, industry-speciic regulatory arrangements.

It is useful to have a framework when evaluating infrastructure policy. As a irst step, it is helpful to deine infrastructure. This article uses a slightly amended version of the deinition suggested by Wharton (1967): infrastructure is the physi

-cal capital and the institutions or organisations, both public and privately owned, that provide economic services and have a signiicant effect, directly or indirectly, on the economic functioning of economic actors (both individuals and irms) but

are external to each actor.

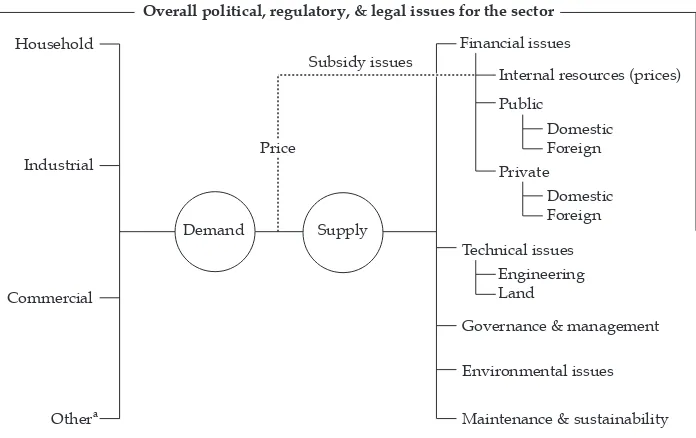

Many factors inluence demand and supply for infrastructure (igure 1).1 The details vary from industry to industry, but on the demand side in Indonesia there are often several distinct markets for infrastructure services. On the one hand,

there is a demand from different types of consumers (household, industrial, com-mercial, and others) in the modern, formal sector of the economy. On the other hand, there is also a demand from small-scale consumers.2

On the supply side, a number of related but separate policy issues exist. Financial concerns naturally loom large for senior policymakers. Technical requirements,

1. The discussion here draws on an earlier article (McCawley 2010).

2. Small-scale consumers of infrastructure services are an important part of the overall

infrastructure market in Indonesia. However, they are generally neglected by large-scale, often state-owned suppliers in the formal sector (see McCawley 2010).

including access to land, often limit the options for the supply of services. Matters

of governance and internal management need close attention. Safeguards such as environmental and social standards affect community expectations. And there

are wider policy considerations as well, such as the overall framework of political,

regulatory, and legal issues within which infrastructure sectors must operate, and

the broad inancial and economic constraints—including pricing policies—set

down for infrastructure industries.

As igure 1 shows, it is inevitable that many issues in the infrastructure sector in Indonesia will be contested by many interest groups. On the demand side, larger consumers of infrastructure services in the formal sector can be expected to

press for increases in supply. Smaller consumers, many of whom are in the infor-mal economy, often resort to imaginative, ad-hoc measures to gain access to

infra-structure. On the supply side, there is a push-and-pull between policymakers and other actors involved in different sectors. Further, the regulatory framework in Indonesia is not well established. Institutional decisions—such as those of the

parliament, the executive, or the Constitutional Court, if not those of local govern-ments—can cause much uncertainty for actors in infrastructure operations.

POST-INDEPENDENCE

There was relatively little growth in the infrastructure sector during the 1950s and

into the 1960s. The previous decades of the 1930s and 1940s had, of course, been dificult ones. Important parts of Java had been well served by the transport and

FIGURE 1 Framework of Policy Issues in the Indonesian Infrastructure Sector

Demand Supply

Household

Industrial

Commercial

Financial issues

Governance & management

Environmental issues

Maintenance & sustainability Price

Subsidy issues

Internal resources (prices)

Private Public

Technical issues Engineering Land

Domestic Foreign

Domestic Foreign

Othera

Overall political, regulatory, & legal issues for the sector

Source: McCawley (2010).

a Includes social and government consumers, for example.

other communications sectors at the beginning of the 20th century,3 but services

in the railways and most other parts of the transport industry steadily declined in

the following decades. By the late 1950s, the dilapidated transport network added considerably to the costs of transporting rice and to the losses within the market

-ing network. A good deal of rice was transported through simple infrastructure systems (carts, carrying-poles, and bicycles) on unsealed tracks. Trains and trucks

carried food supplies to the main cities in Java, while in Sumatra and Kalimantan

considerable use was made of waterways (Mears 1961).

To be sure, President Sukarno had on various occasions announced major infra -structure plans during the 1950s and 1960s. But too often, as on many occasions

since then, ambitious infrastructure plans were not supported with the resources needed. By the beginning of the New Order period, most infrastructure across the nation had long been neglected.

ROADS AND MOTOR TRANSPORT

In the early 1970s, a revolution in road transport began. As the road network grew, and as the economy became more open to foreign investment and imports, a remarkable structural transformation in the road transport system began to occur. Traditional forms of public transport, such as the becak (trishaw) and dokar

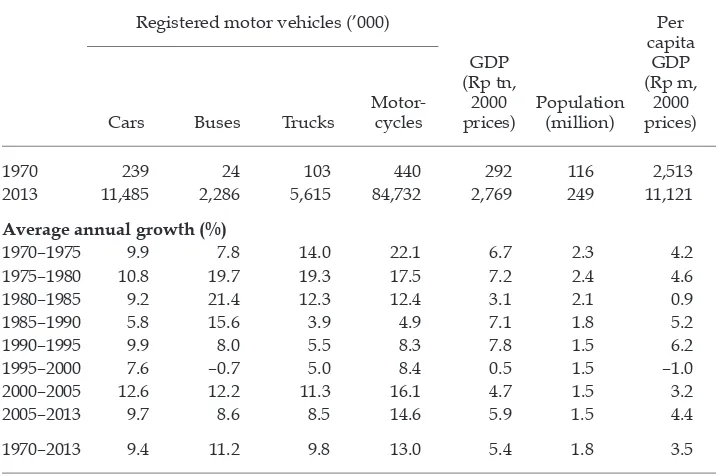

(horse-cart), found it hard to compete with the swelling numbers of buses and small pick-up trucks (often called ‘colts’) appearing on the roads (Booth and McCawley 1981, 8). Indonesian consumers also quickly took to the use of light motorcycles produced by well-known Japanese suppliers such as Yamaha, Honda, and Suzuki. Into the mid-1980s, the numbers of both trucks and motorcycles on Indonesian roads grew by well over 12% per year, signiicantly faster than the economy and the population (table 1).4

These developments were transformative of what is now called ‘connectivity’ in Indonesia. The cost and convenience of both local journeys and long-distance intercity travel improved dramatically. Workers from previously isolated rural areas in Java, such as Gunung Kidul, in Yogyakarta, increasingly took up con

-struction jobs as far aield as Jakarta or even South Sumatra (Dick 1981b, 88).

Circumstances in the outer islands, however, were varied. In some places, rapid

changes took place. In North Sumatra, for example, the road system improved

greatly during the 1970s (Ginting and Daroesman 1982, 71). But in other places, especially in eastern Indonesia, there was less improvement.

3. In a survey of competition between the railways and other modes of transport at the time, Dick (2000, 187) observes that Java, by 1900, already had ‘a sophisticated agro-industrial economy integrated by overlapping networks of telegraphs, telephones, rail

-ways, narrow-gauge tramways and good roads. Nowhere in Southeast Asia could boast better infrastructure. Elsewhere in East Asia, only Japan could compare’.

4. The tables in this article draw on various editions of Statistik Indonesia (BPS 1970–2013a),

whose data are not always consistent or complete. All possible care has been taken to en

-sure accuracy of data in this article. In a few cases, to bridge gaps, extrapolation has been necessary to prepare a full data series. The data shown in the tables are taken to relect the rising demand for better infrastructure in Indonesia.

TABLE 1 Motor Vehicles and Economic Change in Indonesia, 1970–2013

1970 239 24 103 440 292 116 2,513

2013 11,485 2,286 5,615 84,732 2,769 249 11,121

Average annual growth (%)

1970–1975 9.9 7.8 14.0 22.1 6.7 2.3 4.2

1975–1980 10.8 19.7 19.3 17.5 7.2 2.4 4.6

1980–1985 9.2 21.4 12.3 12.4 3.1 2.1 0.9

1985–1990 5.8 15.6 3.9 4.9 7.1 1.8 5.2

1990–1995 9.9 8.0 5.5 8.3 7.8 1.5 6.2

1995–2000 7.6 –0.7 5.0 8.4 0.5 1.5 –1.0

2000–2005 12.6 12.2 11.3 16.1 4.7 1.5 3.2

2005–2013 9.7 8.6 8.5 14.6 5.9 1.5 4.4

1970–2013 9.4 11.2 9.8 13.0 5.4 1.8 3.5

Sources: Data on registered motor vehicles from BPS (1970–2013a)—see footnote 4. Data on GDP and population from Van der Eng (2010), updated to 2013 with data from national accounts and from BPS

(2013b).

The rapid expansion of oil production since the late 1960s and the rise of oil

prices during the 1970s yielded a signiicant increase in public revenue. Around the same time, Indonesia’s increasing export earnings qualiied it for additional

foreign loans. Both revenue sources helped fund road and infrastructure pro-grams in the 1970s and 1980s. Throughout the 1980s, real investment in roads

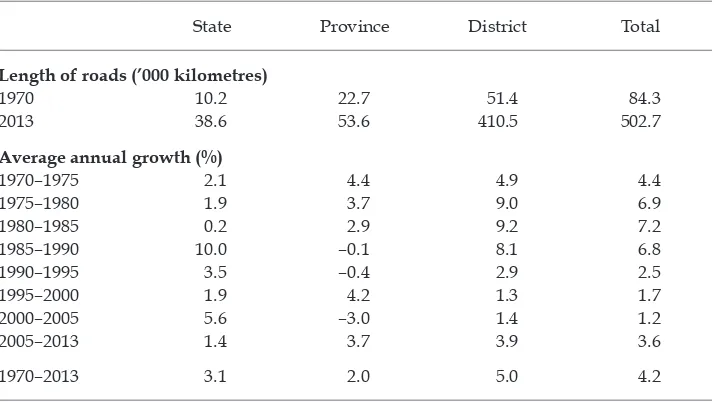

continued to grow at a strong rate of around 7% per year (table 2).

Faced with a tightening iscal situation at the end of the 1980s, policymak

-ers began looking for other ways to inance infrastructure spending. A growing acceptance of the need to mobilise private-sector investment was relected in poli -cies on roads and other main parts of the infrastructure sector. Throughout the

1990s, arrangements such as management contracts and joint ventures between state enterprises and large private irms were entered into for such projects as toll-roads, which involved build–own–transfer and build–own–operate contracts. Partnerships of this kind did not always go smoothly, however, and tendering processes sometimes lacked transparency (Hill 1996, 185).

Investment in roads fell sharply after the 1997–98 Asian inancial crisis. Between

the mid-1970s and the mid-1980s, real investment in local roads at the district

level (relected in the length of roads) had grown by almost 10% per year. Between

1995 and 2005, it slumped to less than 2% per year. One of the much-discussed

features of this slowdown in investment has been the increasing trafic congestion in Java, and especially in Jakarta (Thee and Negara 2010, 304). Demand for road

space in Indonesia has grown much more rapidly than supply. The total length

of roads across the country between 1970 and 2013 grew by slightly more than 4% per year (table 2). In the same period, the number of motor vehicles grew by

around 12% per year. Greater reliance on railways, particularly in Java, would

seem to be urgently needed in the coming decades.

RAIL TRANSPORT

By the beginning of the 1970s, the rail industry had suffered from decades of neglect. The main central railway stations in Jakarta—such as downtown Kota, Gambir, Pasar Senen, and Jatinegara—were chaotic, while the trains themselves were badly maintained. In Central Java, it was reported that the railways were

required to maintain uneconomic routes for social reasons and that revenues

had continued to decline ‘mostly owing to non-payment of fares by the military’

(Partadireja 1969, 39).

In the outer islands, the neglect of the rail industry was, if possible, even more marked. In West Sumatra’s railway system, passenger trafic had declined sharply

in the late 1960s, and more than half of the passenger equipment was more than 70 years old (Esmara 1971, 51). In Aceh, most of the locomotives, which were

wood-ired, were more than 80 years old. The railway had been running at a large

loss for many years (Boediono and Hasan 1974, 50). It ceased operations, in effect, in the early 1970s.

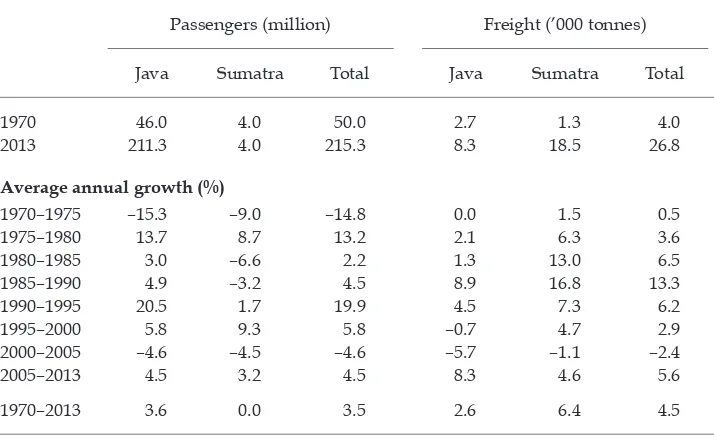

During the next several decades, the industry had mixed fortunes. After a

sharp decline in passenger trafic in the early part of the 1970s, there was a recov -ery and then a generally steady growth in demand. Over the period 1970–2013,

total passenger trafic—almost all of which was in Java—increased at the modest but sustained rate of 3.5% per year (table 3).

TABLE 2 Length of Roads, 1970–2013

State Province District Total

Length of roads (’000 kilometres)

1970 10.2 22.7 51.4 84.3

2013 38.6 53.6 410.5 502.7

Average annual growth (%)

1970–1975 2.1 4.4 4.9 4.4

1975–1980 1.9 3.7 9.0 6.9

1980–1985 0.2 2.9 9.2 7.2

1985–1990 10.0 –0.1 8.1 6.8

1990–1995 3.5 –0.4 2.9 2.5

1995–2000 1.9 4.2 1.3 1.7

2000–2005 5.6 –3.0 1.4 1.2

2005–2013 1.4 3.7 3.9 3.6

1970–2013 3.1 2.0 5.0 4.2

Source: Data from BPS (1970–2013a)—see footnote 4.

The recovery of passenger trafic relected ongoing attempts to improve the overall management of the rail system. These efforts became especially noticeable after the decision was taken in the early 1970s to electrify the system in parts of Java. Main railway stations across Java became much better organised and main

-tained. Nevertheless, despite signiicant improvements, major problems remain. One is the inancial challenge facing state-owned PT Kereta Api Indonesia (KAI).

Prices for railway services, especially passenger travel, are still very low and do

not cover the full costs. PT KAI must therefore rely on uncertain subsidies from the central government. It is dificult for PT KAI to increase tariffs, because of the universal expectation in Indonesia that railway services be provided at low cost, and because of cut-throat competition from operators of high-risk bus and truck transport. These operators often do not cover the full costs of their use of

the road system (Jakarta Post, 29 Sept. 2010, 8 Dec. 2011). Another challenge is the urgent need to fund large investments in other parts of the railway system, most

of which is still badly neglected. Many of the main lines in Java remain single track, and most are in need of repair. The main line in the eastern part of East Java, from Surabaya to Banyuwangi, is still single track, for example.

Looking ahead, it would seem that a resurgence of the rail industry is needed. Signiicant plans for increased investments were listed in the government’s 2011 master plan for Indonesia’s economic development (Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs and Bappenas 2011). In Java, road-trafic density often seems close to breaking point, and in parts of the outer islands there is a growing need

for expanded rail services to transport goods, especially coal, to ports for export or for use in Java.

TABLE 3 Railway Trafic, 1970–2013

Passengers (million) Freight (’000 tonnes)

Java Sumatra Total Java Sumatra Total

1970 46.0 4.0 50.0 2.7 1.3 4.0

2013 211.3 4.0 215.3 8.3 18.5 26.8

Average annual growth (%)

1970–1975 –15.3 –9.0 –14.8 0.0 1.5 0.5

1975–1980 13.7 8.7 13.2 2.1 6.3 3.6

1980–1985 3.0 –6.6 2.2 1.3 13.0 6.5

1985–1990 4.9 –3.2 4.5 8.9 16.8 13.3

1990–1995 20.5 1.7 19.9 4.5 7.3 6.2

1995–2000 5.8 9.3 5.8 –0.7 4.7 2.9

2000–2005 –4.6 –4.5 –4.6 –5.7 –1.1 –2.4

2005–2013 4.5 3.2 4.5 8.3 4.6 5.6

1970–2013 3.6 0.0 3.5 2.6 6.4 4.5

Sources: Data from BPS (1970–2013a)—see footnote 4. GDP and population data from Van der Eng

(2010), updated to 2013 with data from national accounts and from BPS (2013b).

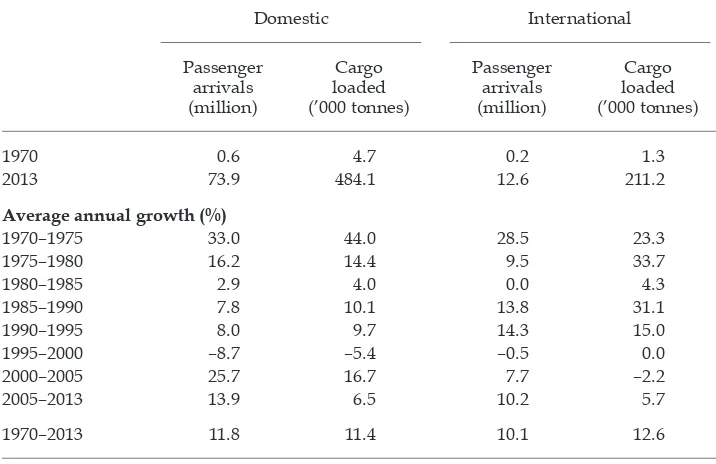

AIR TRANSPORT

Like other parts of the infrastructure sector in Indonesia, at the end of the 1960s the

airline industry was in a neglected state. The state-owned PT Garuda Indonesia Airways had a near-monopoly in the main domestic routes, and international

car-riers did not see Indonesia as an encouraging market. Prospects for the industry began to pick up quickly, however, as overall economic conditions improved. In

recent decades, air services in Indonesia have expanded rapidly. Over the period

1970–2013, both domestic and international services grew by around 10% per year (table 4)—signiicantly faster than the economy. Indeed, developments in the airline industry over the past ive decades provide useful lessons on competi

-tion policy for other parts of the infrastructure sector. For most of the irst three decades, an inward-looking, protectionist approach inluenced Indonesian policy

towards regulation of the industry. The situation changed dramatically after the

1997–98 inancial crisis, when much more vigorous competition became the norm

in Southeast Asia.

Despite the restrictions on expansion imposed by the dominance of Garuda, growth during the 1970s, beginning from a low base, was very rapid. Across Indonesia, regional airline services improved markedly, greatly facilitating ofi

-cial and business travel and boosting tourism in well-known centres such as Bali and Yogyakarta. In Yogyakarta, the number of lights to Jakarta operated by main airlines expanded from four per week in 1968 to four per day in the late 1970s (Hill and Mubyarto 1978). Throughout the decade, domestic passenger trafic grew by around 20% per year (table 4).

TABLE 4 Air Trafic, 1970–2013

Domestic International

Source: Data from BPS (1970–2013a)—see footnote 4.

This burst of growth in domestic air travel slowed somewhat during the 1980s, relecting a slowdown in the Indonesian economy and a reluctance by regula -tors to encourage competition in the industry. There was later a recovery into

the 1990s, until the 1997–98 inancial crisis led to a short but sharp contraction in

domestic and international air services in Indonesia.

The 1997–98 crisis forced reform in the industry, both in Indonesia and in other parts of Southeast Asia (Damuri and Anas 2005). Deregulation and liberalisa

-tion allowed the entry of new, low-cost carrier irms such as Lion Air, Adam Air, and Citilink (a Garuda subsidiary), which were soon competing vigorously and transforming the airline business in Indonesia. Domestic passenger trafic, espe

-cially, began to expand rapidly. In the decade to 2013, the number of domestic passengers grew by around 15% per year, rising from 18.1 million to 73.9 million. Many of the main airline terminals across Indonesia are now packed for much of the time. In Jakarta, in 2011, more than 51 million passengers passed through Soekarno–Hatta airport, around 130% above the original capacity of 22 million

planned in 1985 (Jakarta Post, 3 Aug. 2012).

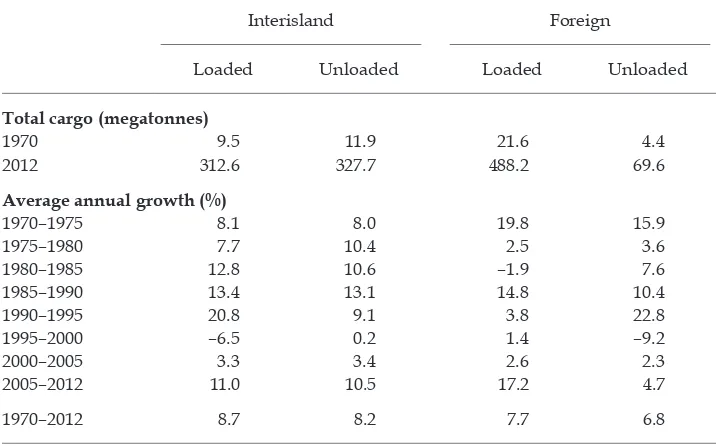

SHIPPING

The shipping industry, including ports, is part of Indonesia’s connectivity sys

-tem. Three dimensions of connectivity are relevant in Indonesia’s water transport industry: intra-island connectivity, interisland linkages, and international trans -port arrangements (Baird and Wihardja 2010, 159).

In some parts of the outer islands, water transport systems provide the most important form of intra-island connectivity. In South Kalimantan, for example,

‘rivers and canals . . . are like roads and highways in Java’ (Partadireja 1970). In

Riau, a province in southern Sumatra, most of the towns and most of the

popula-tion are located along 15 navigable rivers, so the local system carries large vol -umes of cargo and passengers.

Interisland and international shipping systems, which often rely on substan

-tial port facilities, attract more attention from policymakers than do the smaller intra-island links. In the late 1960s, the sailing time of ships was said to be greatly limited because many ports were silted up, and it was reported that only 30% of navigation buoys worked (Panglaykim, Penny, and Thalib 1968, 23).

As was the case in other parts of the infrastructure sector, the use of shipping services recovered during the 1970s and strengthened during the latter part of

the 1980s and into the next decade (table 5). But the 1997–98 crisis and the subse -quent prolonged slowdown had a severe impact on shipping. It was not until the

Indonesian economy began to return to higher rates of growth, around 2007, that the level of activity in the industry showed a marked improvement.

Competition and regulation have been central topics of much of the policy dis

-cussion about shipping in Indonesia. In the late 1960s, costs, prices, and competi

-tion arrangements all contributed to high levels of ineficiency in the shipping industry (both in the use of ships and in the ports). At the time, as in the succeed -ing decades, three issues were frequently mentioned as need-ing attention.

First, the levels of costs and prices in the industry were a subject of constant

comment (Ray 2003, 262). Domestic freight rates in Indonesia were very high: the

cost of shipping cement by sea from Gresik (near Surabaya) to Jakarta, for exam

-ple, was higher than from Tokyo to Jakarta. Second, the competitive arrange

-ments in the industry did not encourage orderly and eficient market conduct.

Sometimes there was unfair competition from non-commercial vessels such as naval or other government-owned ships. At other times, nationalist and protec-tionist ideas restricted entry.5 Third, the shipping industry was hampered by poor management and by the existence of a myriad of local payments that needed to be made in the ports.

These ineficiencies in the ports, bureaucratic delays, and informal payments are universally regarded as unacceptable but are apparently hard to overcome. They remain major problems in the Indonesian shipping industry.

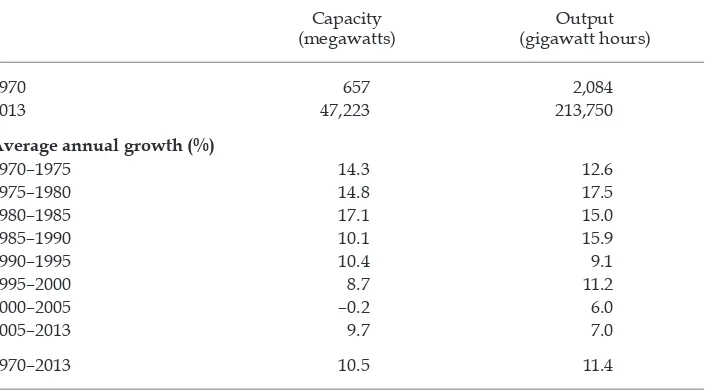

ELECTRIC POWER

In the early 1970s, much of Indonesia was still very poorly served with electricity

from the national electricity company, Perusahaan Listrik Negara(PLN). Across

the nation, a good deal of electricity was generated by the private sector, either by the larger private manufacturing irms or large hotels (mainly for their own

5. In a discussion of Law 17/2008 on Shipping, Dick (2008, 404) surveyed the shipping regulations and concluded that ‘the extra costs of ineficient Indonesian-lag ships have to be borne as a tax on the nation’s trade’.

TABLE 5 Sea Cargo Handled in Ports, 1970–2012

Interisland Foreign

Loaded Unloaded Loaded Unloaded

Total cargo (megatonnes)

1970 9.5 11.9 21.6 4.4

2012 312.6 327.7 488.2 69.6

Average annual growth (%)

1970–1975 8.1 8.0 19.8 15.9

1975–1980 7.7 10.4 2.5 3.6

1980–1985 12.8 10.6 –1.9 7.6

1985–1990 13.4 13.1 14.8 10.4

1990–1995 20.8 9.1 3.8 22.8

1995–2000 –6.5 0.2 1.4 –9.2

2000–2005 3.3 3.4 2.6 2.3

2005–2012 11.0 10.5 17.2 4.7

1970–2012 8.7 8.2 7.7 6.8

Sources: Data from BPS (1970–2013a)—see footnote 4. For selected years (2000–2004, 2007, 2008, and

2011), data were taken from the CEIC Indonesia Premium Database.

Note: Annual estimates for the years between 1970 and 1974 for interisland cargo were calculated by

projecting the GDP growth rate for 1975 backwards, and those for foreign cargo by projecting real growth of exports and imports for 1975 backwards.

consumption) or by plantations and estates in some rural areas. All sorts of substi

-tutes for a reliable public supply were used as well. In late 1972, when widespread power cuts occurred more frequently in Jakarta than they do now, prices of can

-dles, portable generators, kerosene, and pressure lamps rose by as much as 50%. These increases affected many Jakarta citizens, most of whom at that time were

not even connected to the formal electricity supply.

Total installed capacity in the public electricity system in Indonesia in the late 1960s was less than 700 megawatts and production was less than 20 kilowatt hours per person (compared with around 7,000 kilowatt hours per person in the United States in 1970). In reality, more than 70 years after public supplies of elec

-tricity were irst introduced in Indonesia in the 1890s, only a small proportion of

the Indonesian population had access to electricity. During the 1970s, however,

the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank supported investments in electric power projects, beginning from a modest base (Thompson and Manning 1974). Both capacity and output grew by around 15% per year during 1970–80 (table 6).

Investment in the expanding power industry was partly inanced out of domes

-tic resources but often drew on international funding of one sort or another, such as support provided by multilateral investment banks or export credits. The large,

600-megawatt Asahan power plant and aluminium smelter in North Sumatra,

opened by President Soeharto in 1982, involved a total investment of around $2 billion. The bulk of the inance was provided by a group of Japanese private com -panies and the Japanese government (75%), while the remaining funding was

provided by the Indonesian government (Ginting and Daroesman 1982, 68).

In addition to capacity and output growth in electric power during the 1980s, there were two other developments in the industry. First, increasing attention

was given to rural electriication. Access to electricity in rural areas of Indonesia was extremely low during the 1970s. A rural electriication program in Bali in the

TABLE 6 Public Supply of Electricity Capacity and Output, 1970–2013

Capacity (megawatts)

Output (gigawatt hours)

1970 657 2,084

2013 47,223 213,750

Average annual growth (%)

1970–1975 14.3 12.6

1975–1980 14.8 17.5

1980–1985 17.1 15.0

1985–1990 10.1 15.9

1990–1995 10.4 9.1

1995–2000 8.7 11.2

2000–2005 –0.2 6.0

2005–2013 9.7 7.0

1970–2013 10.5 11.4

Source: Data from BPS (1970–2013a)—see footnote 4.

1970s had proved successful (Bendesa and Sukarsa 1980, 48) and had encouraged

PLN to consider using similar approaches elsewhere. By the late 1970s, PLN and

other donors were actively supporting rural electriication programs in various parts of Indonesia (McCawley 1978, 61).

Second, structural change was occurring within the industry. In the late 1980s, as on many occasions since then, the Indonesian government pointed to the

pos-sibility of expanding the gas industry to support electricity production. But in the event, this proved dificult: there was already an increasing reliance on coal (Conroy and Drake 1990, 14). For example, the large, 4,000-megawatt electricity plant at Paiton, in East Java, built during the 1990s, is coal-ired (Wells 2007).

The 1990s brought two further major changes in the industry’s operating envi

-ronment. The irst was the announcement of ambitious plans to open the indus -try to private investment. By the late 1990s, more than 20 private companies had

expressed interest in building power stations, especially with an eye to providing

power to industrial consumers. Reporting on these developments, Soesastro and Drysdale (1990, 29) noted that ‘similar schemes for private sector participation in

the development of infrastructure are also being considered in the management of container terminals in a number of Indonesian ports’.

This emphasis on private investment came at a cost. Concerns about debt lev

-els, especially levels of foreign private debt, soon became signiicant (Muir 1991, 3). In mid-1991, the governor of Bank Indonesia, the central bank, reported to par

-liament that the country’s offshore commercial loans in March of that year stood at $16 billion, up by $10 billion from a year earlier. Concerns that the rising levels of debt were related to doubtful investments in infrastructure were a harbinger of the problems that would emerge in the power industry at the end of the decade

(Wells 2007).

In the 1990s, Van der Eng (1993, 26) noted that the government was looking for large-scale investments from the private sector but that private-sector invest

-ment had not proceeded quickly, ‘because there is as yet no satisfactory outcome

to negotiations over pricing. . . . If the price PLN pays itself is too low, electricity

generation will not be proitable—and therefore not of interest—to private irms’. Kristov (1995, 73) observed that ‘price has become a controversial issue—both the retail price private producers would charge the public, and the wholesale price at which they would sell in bulk to the state utility, PLN’. After a careful analysis,

Kristov concluded that the cost of supplying electric power during most of the

1980s was more than 40% higher than PLN’s average sales revenue.

The second major change to affect trends in the power industry during the

dec-ade was the 1997–98 Asian inancial crisis. The crisis caused a sharp depreciation in the value of the rupiah, harming the revenue lows and balance sheets of many companies across Indonesia. Nowhere was this more marked than in the power industry; it became clear that the strategy of the early 1990s of relying on private foreign investment to fund the expansion of power plants was seriously lawed

(Wells 2007).

The dificult experience during the 1997–98 crisis had a lasting inluence on the approach of policymakers towards infrastructure policy during 2000–2010. On coming to ofice in 2004, the administration of President Yudhoyono responded to the infrastructure shortages in several ways, including by setting speciic tar -gets for expansion for each industry. In the electric power industry, for example,

two 10,000-megawatt fast-track programs to expand generating capacity were announced, the irst in 2006 and the second in 2010. This approach of setting tar

-gets, however, had limited success: there were delays, and both programs pro -ceeded rather more slowly than expected.

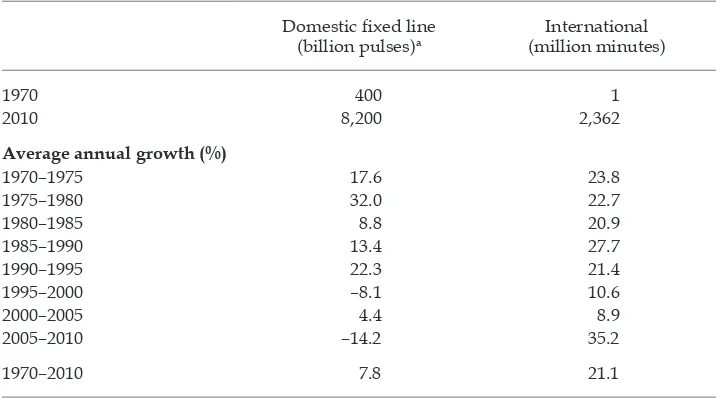

TELECOMMUNICATIONS

Telecommunications has been one of the most dynamic industries in Indonesia

during the past 50 years. Developments in the industry have gone through four distinct phases.

In the irst phase, during the 1970s and 1980s, telecommunication facili -ties expanded rapidly as new technologies, such as interisland microwave

systems and, from 1976, the Palapa communication satellites owned by Telecommunications provider PT Indosat, were used to expand links across the country, supplementing the overland and submarine cable systems. Supply long struggled to keep up with demand. In the main urban areas, such as Jakarta

and Bandung, shortages of telecommunication facilities were acute (Grey 1984).

Nevertheless, the use of both domestic and international telephone connections increased rapidly (table 7).

The second phase began in 1989, when private participation, through public– private partnership arrangements, was permitted in the ixed-line industry, relect

-ing the broad trend of encourag-ing private-sector participation in infrastructure (Lee and Findlay 2005). In the event, this phase of market-oriented reform was unsuccessful. The contract-based partnerships system provided only short-term solutions for the acute lack of capacity.

TABLE 7 Telephone Calls, 1970–2010

Domestic ixed line

(billion pulses)a (million minutes)International

1970 400 1

2010 8,200 2,362

Average annual growth (%)

1970–1975 17.6 23.8

1975–1980 32.0 22.7

1980–1985 8.8 20.9

1985–1990 13.4 27.7

1990–1995 22.3 21.4

1995–2000 –8.1 10.6

2000–2005 4.4 8.9

2005–2010 –14.2 35.2

1970–2010 7.8 21.1

Source: Data from BPS (1970–2013a)—see footnote 4. Estimates for 2001–4 are interpolated between 2000 and 2005, assuming a constant growth rate of 8.9% over the period.

aFixed-line telephony, excluding calls made via mobile telephone.

A third period of reform began in 1999, when Law 36/1999 on Tele communica

-tions established a revised framework for opera-tions. A duopoly structure was created in ixed-line operations, accompanied by a wider, pro-market approach. These reforms acknowledged the importance of competition and of a sound regu

-latory regime, although there were still limits on market entry.

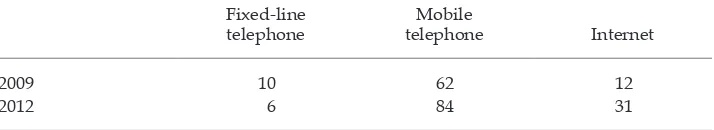

Under the revised framework, a fourth and very dynamic stage has emerged in recent years. New telecommunication technologies have looded into Indonesia, within a highly competitive market structure. Local irms such as Telkomsel, Indosat, and Mobile-8 (Smartfren), supported by multinational companies such as Samsung, LG, and Nokia, are now prominent in the market, offering all kinds of discounts on mobile phones and advertising widely. Customers are moving away from the old ixed-line system—table 7 shows that the use of domestic ixed-line calls dropped sharply during 2005–10—and taking up mobile phones with enthusiasm. Internet use has expanded rapidly as well (table 8).

These recent developments illustrate the gains that can be made in the infra

-structure sector when an appropriate regulatory regime is established. Perhaps the main lessons from the burst of growth in telecommunications in Indonesia during the past decade are the importance of encouraging markets to work, of

facilitating the entry of new technology, and of attracting new investment. Careful

market design, relying on an effective regulatory regime, is needed to enable

capital-intensive infrastructure industries such as telecommunications to develop

quickly (Magiera 2011).

WATER, SANITATION, AND IRRIGATION

The management of water and sanitation remains one of the most pressing issues

in infrastructure policy in Indonesia. Yet it is extremely dificult to tackle the prob

-lems in the industry, because attention to cost recovery is often considered irrel

-evant (Asian Development Bank 2012, 8). The results are widespread. Access to potable water from municipal water supplies is extremely limited, so elite con

-sumers opt to rely largely on expensive bottled water. Frequent looding occurs in both urban and rural areas during rainy seasons. Adequate public sanitation

services are almost non-existent in many parts of Indonesia. And irrigation policy poses many challenges.

The 1970s saw some improvements in municipal water supply. However, as was the case in other parts of the infrastructure sector, institutions in the formal

sector—such as modern hotels, large factories, and some elite residential establish

-ments—relied little on the public system, preferring to install their own systems.

TABLE 8 Households with Access to Telecommunications, by Technology, 2009–12 (%)

Fixed-line telephone

Mobile

telephone Internet

2009 10 62 12

2012 6 84 31

Source: Data from BPS (1970–2013a)—see footnote 4.

During the next few decades there were attempts to improve the public supply system by strengthening the extensive urban network of local water-supply establishments, or Perusahaan Daerah Air Minum, of which there were more than 300. But these establishments were constrained by bureaucratic con

-trols and by enforced low prices. Across Indonesia, much of the population opted out of any relationship with the public system, choosing instead to rely on infor -mal water suppliers and on natural supplies of water. In rural areas, even in s-mall towns, much of the population depended on springs and wells. This is hardly

sur-prising, because simple local systems often provide better and more cost-effective supplies of water than larger systems (Perkins 1994).

Attention to large-scale sanitation services has been similarly lacking for many

decades. Communities resist paying for services that they have come to expect

public agencies to provide for free. Government agencies have therefore found it dificult to raise monies to fund public sewerage systems. In urban areas, pri

-vate septic facilities are widely used, but their installation and maintenance are

poorly regulated. Serious externalities in the form of environmental and health

problems are liable to occur. Frequent looding during rainy seasons is another major water-management issue. Every few years, large-scale looding in Jakarta leaves up to 1 million people needing temporary refuge. Widespread looding in other areas of Indonesia receives less publicity but imposes great social and

economic costs.

Managing irrigation and drainage systems has been vital to Indonesia’s agri -cultural economy since the 19th century. After independence in 1945, attempts

were made to expand the irrigation system but existing systems were neglected. As Booth (1977, 50) noted, ‘the systems laid out by the colonial government dur

-ing the prewar period fell into an almost unchecked decline between 1940 and 1968’. During the 1970s, agricultural development programs supported by for

-eign donors and the Indonesian government provided funding to rehabilitate and expand irrigation networks, particularly in Java and Bali. The eficiency of irriga -tion systems depends crucially on the extent to which opera-tion and maintenance are extended downstream to the tertiary levels of the systems (Van der Eng 1996, 41, 156). Special attention was also given to the expansion of irrigation facilities

in the outer islands, to support the national transmigration programs being pro -moted at the time.

Signiicant efforts were made during the 1980s to expand the irrigation sys -tem. Between 1969 and 1994, irrigation systems serving 2.5 million hectares were

rehabilitated and 1.7 million hectares of new irrigation systems were developed. However, inancing maintenance activities continued to be dificult. Around 60% or more of operation and maintenance budgets were reported as having been spent on staff costs, leaving little available for routine maintenance (Vermillion, Lengkong, and Atmanto 2011, 2). More recently, since the 1990s, discussion about investment priorities in the irrigation industry has been closely linked to plans for food security. One view is that food security can be strengthened by the develop

-ment of major food-growing areas in the outer islands. But the economic feasibil -ity of large investments in new irrigation projects in the outer islands depends,

in turn, on the economic feasibility of new food estates outside Java. Under these circumstances, the development of large irrigation projects of this kind is fraught

with uncertainty.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR INFRASTRUCTURE POLICY

It is clear from this survey of developments across the infrastructure sector during

the past ive decades that a wide range of issues need to be considered in formu

-lating infrastructure policy in Indonesia (igure 1).

Demand

Policymakers in Indonesia have rarely been prepared to address community expectations about the supply of infrastructure services. The idea that utilities should not be run for proit but should instead serve the public underpins the

expectation of low prices for utilities. Populist political leaders have often

encour-aged consumers to expect that utility services (often referred to as a basic need) be provided at subsidised prices. The sources of these subsidies are rarely directly mentioned, but it seems clear that advocates of low prices believe that the subsi

-dies should be paid for by the government, or by the (mostly) state-owned utili

-ties providing the infrastructure services, or perhaps, in one way or another, by

the private sector.

Related to the idea that utilities should serve the public is the distinction between the provision of services to small and large consumers. The market for providing utility services to small consumers in Indonesia is very large. Many

authors writing in BIES about the infrastructure sector have referred to the vari -ous challenges of providing services to consumers in the small-scale and informal

economy (Dick 1975a, 1975b, 1981a, 1981b; McCawley 1978; Gibson 1986; Hughes 1986; Munasinghe 1988; Perkins 1994). However, the larger utilities in the formal state-owned sector ind it very dificult to reach out to this market. Until formal

institutions such as the large state-owned utility enterprises can design programs

to reach out to the informal economy, they will continue to be seen as alien to the

needs of ordinary rakyat (people).

Supply

No single constraint holds back the supply of infrastructure in Indonesia. Rather, numerous issues combine to constrain growth.

Finance

Investors and inancial specialists in Jakarta often say that money is not the problem holding back infrastructure development in Indonesia. They argue that it is usu

-ally not dificult to raise funds for infrastructure activities in Indonesia—whether from banks or from bond issuers—provided that the borrowers provide appropri

-ate guarantees to the inanciers. They suggest that as long as technical problems,

such as those of project design and land access, and pricing arrangements are

clari-ied in a satisfactory way, inance will be forthcoming from the markets.

In a detailed survey of Indonesia’s experience with private investment in the

power industry in the 1990s, Wells (2007) provides a more sceptical view. He traced

the processes between 1990 and 1997 by which PLN signed 26 agreements with

private investors for generation projects. The investments represented around

11,000 megawatts and provided at least $13 billion of investment. But when the 1997–98 crisis struck, those arrangements quickly ran into trouble, because PLN’s revenue lows were in rupiah while its obligations were in US dollars. Extended contract disputes broke out when PLN tried to renegotiate the terms of the deals

agreed to with foreign investors. Wells notes that the whole process of raising

private inance and entering into long-term arrangements with foreign investors was dificult for PLN, and concludes that ‘private ownership of generating capac

-ity is not the only possibil-ity, nor should it be a goal in itself. . . . If Indonesia can do no better in new arrangements, privatization is simply too costly. Borrowed funds and state ownership, with all their problems, would be preferable’ (362).

Technical Issues

There is no doubt that there is a shortage of well-prepared and well-documented projects in Indonesia available for investors to examine. This shortage became

clear around the time of several infrastructure summits during the period of the Yudhoyono administration. The details of projects provided to potential

inves-tors at these summits were often very slim. In some cases, websites purporting to provide data on large projects turned out to be blank. In the event, the response to the summits was disappointing. Hardly any of the projects offered at the irst summit were taken up, and at the second summit, ‘although potential investors . . . generally showed wary optimism, most opted for a wait-and-see approach’ (Lindblad and Thee 2007, 26).

A lack of detailed project data was also apparent in the government’s master plan for Indonesia’s economic development (Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs and Bappenas 2011). The master plan provided a strategic framework for

infrastructure investment across Indonesia, with an emphasis on supporting the

development of economic corridors. It contained a pipeline of possible projects, but detailed supporting project proposals were often not available in the imple -menting sectoral ministries.

A related technical issue concerns access to land. Policymakers in Indonesia recognise that a lack of access often delays project construction. In recent years, a range of steps have been taken to try to make it easier to obtain land for infrastruc -ture development, including promulgating a new land law. Implementing the law

has proved dificult, however; legal clarity in obtaining access to land is often lacking. Henderson, Kuncoro, and Nasution (1996) discussed land access in their survey of development problems in Jabotabek (Jakarta, Bogor, Tangerang, and Bekasi). They pointed to very poor land market institutions of ‘weakly deined property rights, particularly for traditional low income residents’ and ‘complete lack of active land use planning’ (71) as major problems.

It seems clear that uncertain land titling is a major disincentive for investors.

Investors are unlikely to be ready to commit large sums of money to long-term

investment in projects when legal titles to the land for the projects are unclear.

Governance and Management

It is well known that there are sometimes problems of governance and manage

-ment in the utility industry in Indonesia. Managers of utilities sometimes come

under strong political pressure, and in recent years some prominent senior

man-agers of state-owned utilities have been found guilty of corrupt practices. These problems have attracted regular comment in BIES, both in the Survey of Recent Developments series and in other articles (see, for example, Mardjana 1995).

Other, more detailed aspects of project implementation and organisation

have prevented projects from getting underway. Thompson and Manning (1974,

72), for example, reported that procurement was one of the most serious issues

the World Bank faced in implementing projects in Indonesia in the early 1970s.

Obstacles such as uncertain tax provisions for contractors, poor coordination between government agencies, sudden changes in import and customs proce

-dures, and inlexible budget procedures for Indonesian government agencies all

hindered projects.

Dick (1985, 111) emphasised a different set of management issues when he pointed

to the need for improvements in the organisation and regulation of the shipping industry. He argued that there was too often a tendency to invest purely in

physi-cal capital in ports rather than consider how both organisational and regulatory practices could be improved. Political leaders and senior oficials often favoured improvements in physical capital because these changes were visible and could be pointed to as tangible signs of achievement. Improvements in organisation, how

-ever, required time and patience, and were less likely to yield easy-to-see beneits. Dick also noted that the regulatory processes in the industry were often protec -tionist and discouraged the types of structural reform that would increase

produc-tivity. He concluded that ‘a more eficient interisland shipping industry therefore requires not so much the commitment of more resources but better organisation to improve the utilisation of existing resources’ (113). More recently, Ray (2003, 262) noted that the shipping industry in Indonesia continued to be hampered by low levels of eficiency in ports, caused by a lack of competition.

Environmental and Social Issues

In principle, there are strong arguments for giving more emphasis to environmen-tal and social issues in plans to expand the infrastructure sector. In practice,

how-ever, these issues have often received relatively little attention in oficial circles.

One of the most important dilemmas facing energy planners in Indonesia is to

what extent the country should aim to rely on coal for energy security (Narjoko

and Jotzo 2007, 163). On the one hand, coal is currently the cheapest option for generating electricity. Also, the processes for the construction and management of

coal plants are well known and relatively easy to implement. On the other hand, coal brings a range of environmental problems. The coal used in Indonesia for power generation is usually of a low grade—the cheapest but most polluting fuel available. Further, some of the mined coal reserves are in protected forests. Over

time, power plants using this coal would worsen air pollution and emit much

larger amounts of carbon dioxide than other power-supply options.

Narjoko and Jotzo suggested that the main alternatives to the use of coal for baseload power generation in Indonesia are geothermal and nuclear. But increased reliance on either of these would pose problems as well. Careful decisions will be

needed on the sources of electric power as the demand for energy grows.

Regulatory Matters

Regulation refers to the ‘rules of the game’ (aturan main) that set guidelines for activities within a sector or an industry. The main regulations affecting the infra-structure sector in Indonesia are political and informal pressures, legal and regu-latory arrangements, and pricing controls.

Political and Informal Pressures

The literature on the interrelation between the infrastructure sector and politics

in Indonesia is relatively scarce. Davidson (2015) recently discussed aspects of

political factors inluencing the roads industry, but this topic has not been a focus

of studies in BIES. Dick (1985, 113) analysed the role of lobby groups in the ship

-ping industry, expressing concern about the results for eficiency. One of the main shipping lobby groups, the Indonesian National Shipowners Association, had pushed during the late 1970s and early 1980s to preserve the ‘rights’ of pribumi (indigenous Indonesian) companies while giving no support to the expansion of strong and progressive (often non-pribumi-owned) companies. The regulatory

systems in the shipping industry therefore tended to discourage the most efi

-cient irms from expanding while helping the least efi-cient irms to remain in business.

Legal and Regulatory Arrangements

Many laws, regulations, and, especially, ministerial decisions apply to the infra -structure sector, and, as is the case in other parts of the Indonesian legal system,

their implementation is fraught with dificulty and confusion. In 2004, for exam

-ple, the newly established Constitutional Court took it upon itself to issue a deci -sion on the constitutional legality of matters in the electric power industry.

The dificulties with the Constitutional Court arose following the enactment of Law 20/2002 on Electricity, which gave the government the authority to liberalise the power industry and allow the entry of private irms. A group consisting of labour workers, former PLN employees, and NGO representatives who opposed the unbundling of PLN’s generation, transmission, and distribution operations

challenged the legality of the new law. They argued that the law violated Article 33 of the Constitution, which provides that ‘economic sectors which are important

to the state and crucial for the welfare of the people are controlled by the state and must be developed to give the maximum beneit to the people’. Following hearings, the Constitutional Court annulled the new law in December 2004 and reinstated Law 15/1985 on Electricity (Soesastro and Atje 2005, 24–25; Butt and Lindsey 2008, 248). With the annulment, PLN again became the sole electricity distributor, while also acting as the regulator.

The unexpected intervention of the Constitutional Court in the electric power

industry immediately increased the regulatory risks in many sectors of the econ -omy. The use, in particular, of the vaguely worded Article 33 of the Constitution to underpin the judgement greatly widened the opportunities for special-interest groups to oppose reforms that might reduce the role of the state in any particular sector. Soesastro and Atje (2005, 30) concluded that ‘the potential implications of

this for the future of the Indonesian economy are far-reaching’.

The sympathy for economic nationalism which appears to underpin rulings of

this kind has distinct anti-market tones. Many observers have noted that there is a strong preference in Indonesia for state control of key sectors. Soesastro and Atje, for example, said, ‘The state should indeed be seen as custodian of Indonesia’s natural resources, but there is no reason why it should not exercise this function indirectly, through supervision and regulation’ (30).

Pricing Controls

The regulation of pricing in the infrastructure sector is widespread in Indonesia. The overall effect is to impose widespread price suppression, which has many

consequences for both demand and supply. This approach has extremely impor

-tant implications for the management of the sector, and for the inancial lows

through the sector.

Expectations that regulated utility prices will be kept low are widely held by the public, having been encouraged by populist political leaders ever since inde

-pendence in 1945. But senior economic advisers in government argue that irm ceilings are needed on the budgetary costs of subsidies. In practice, faced with dificult political and economic trade-offs, policymakers swing back and forth in their views (and their resolve). At times, when subsidies have become so large as to be a signiicant burden on the national budget or on state-owned utilities, poli

-cymakers have expressed their intention to reduce subsidies. Familiar arguments are rehearsed: that the burden of the subsidies on the budget is too large and that, in any case, the subsidies are undesirable because the beneits do not reach the poor. Sometimes policymakers have been successful in increasing prices for a period, although the real impact of the increases has usually been eroded over time. And sometimes policymakers have increased prices, only to reduce them again in the face of public pressure.

The public-policy debate is missing a clear and direct explanation to the

Indonesian people that—one way or another—it is they, the consumers of infra-structure services, who must pay the costs of supplying these services. There are various ways of paying: directly, through systems of user charges, or indirectly,

through combinations of taxation charges.

Much of the debate also fails to discuss the overall implications of price suppres -sion in infrastructure. This topic features in many articles in BIES, from its earliest

issues: McCawley (1970) and Kristov (1995) focused on electricity prices; Booth (1977, 58) discussed water charges for irrigation; Dick (1981a, 1981b) raised the topic in articles on urban public transport; and Conroy and Drake (1990, 15–16), Muir (1991, 23), Soesastro and Atje (2005, 27–29), and Kong and Ramayandi (2008,

16) carefully dissected energy and pricing issues.

CONCLUSION

This survey set out, irst, to provide an overview of the main developments in the infrastructure sector in Indonesia during the past ive decades, and second, to consider what the main policy and management bottlenecks in infrastructure appear to be.

The overview of main developments indicates that, in broad terms, most parts of the sector have expanded considerably but that the needs remain acute for fur -ther expansion and for attention to the maintenance of existing facilities. Demand for infrastructure is high, especially since the regulated prices set for

infrastruc-ture services are often low. But access can be dificult because of shortages of infra

-structure, and quality is often unsatisfactory because of poor maintenance and indifferent management. These problems of access are exacerbated by the regula

-tion of prices; suppressed prices limit the inancial capacity of the public utilities and discourage irms in the private sector from investing in infrastructure. This overview also points to the markedly different performances of the industries in which pro-competitive policies have been applied (air transport, telecommunica -tions, and roads and motor transport) and those in which more traditional

poli-cies of close regulation have restricted the operations of markets (rail transport,

shipping, electric power, and water, sanitation, and irrigation).

In many ways, the policy and management bottlenecks in the infrastructure sector are a microcosm of the problems of the overall management of government

in Indonesia. It is dificult to coordinate policy across the silos of the infrastruc

-ture sector; it is hard for the private and public sectors to work together; clearer

rules of the game and more effective regulatory arrangements are needed. None

of these problems are new in Indonesia, neither within infrastructure itself nor within the public sector overall.

Many of these problems hampered the government in the 1950s and 1960s.

They continue to do so today. Boediono (2005) discussed the central issues of

public-sector management in Indonesia when he emphasised the importance in

government of having a clear strategy, of implementing the strategy in a consist-ent way, and of needing to strengthen law enforcemconsist-ent. Boediono was writing

about the overall management of the economy, but these principles also identify the steps that need to be taken to strengthen infrastructure policy more specii -cally in Indonesia.

REFERENCES

Asian Development Bank. 2012. Indonesia: Water Supply and Sanitation Sector; Assessment Strategy and Roadmap. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Baird, Mark, and Maria Monica Wihardja. 2010. ‘Survey of Recent Developments’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 46 (2): 143–70.

Bendesa, I. K. G., and I. M. Sukarsa. 1980. ‘An Economic Survey of Bali’. Bulletin of Indone-sian Economic Studies 16 (2): 31–53.

Boediono. 2005. ‘Managing the Indonesian Economy: Some Lessons from the Past’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 41 (3): 309–24.

Boediono, and Ibrahim Hasan. 1974. ‘An Economic Survey of D.I. Aceh’. Bulletin of Indone-sian Economic Studies 10 (2): 35–55.

Booth, Anne. 1977. ‘Irrigation in Indonesia Part I’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 13 (1): 33–74.

Booth, Anne, and Peter McCawley (eds). 1981. The Indonesian Economy during the Soeharto

Era. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press.

BPS (Badan Pusat Statistik). 1970–2013a. Statistik Indonesia: Statistical Handbook of Indonesia.

Jakarta: BPS.

———. 2013b. Proyeksi Penduduk Indonesia: Indonesia Population Projection, 2010–2035.

Jakarta: BPS.

Butt, Simon, and Tim Lindsey. 2008. ‘Economic Reform when the Constitution Matters: Indonesia’s Constitutional Court and Article 33’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 44 (2): 239–62.

Conroy, J. D., and P. J. Drake. 1990. ‘Survey of Recent Developments’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 26 (2): 5–41.

Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs and Bappenas. 2011. Masterplan: Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia Economic Development 2011–2025. Jakarta: Coordinating Min -istry of Economic Affairs.

Damuri, Yose Rizal, and Titik Anas. 2005. Strategic Directions for ASEAN Airlines in a Glo-balizing World: The Emergence of Low Cost Carriers in South East Asia. Final report, REPSF Project 04/008, ASEAN–Australia Development Cooperation Program II.

Davidson, Jamie S. 2015. Indonesia’s Changing Political Economy: Governing the Roads.

Cam-bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Dick, Howard. 1975a. ‘Prahu Shipping in Eastern Indonesia Part I’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 11 (2): 69–107.

———. 1975b. ‘Prahu Shipping in Eastern Indonesia Part II’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 11 (3): 81–103.

———. 1981a. ‘Urban Public Transport: Jakarta, Surabaya and Malang Part I’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 17 (1): 66–82.

———. 1981b. ‘Urban Public Transport Part II’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 17 (2): 72–88.

———. 1985. ‘Interisland Shipping: Progress, Problems and Prospects’. Bulletin of Indone-sian Economic Studies 21 (2): 95–114.

———. 2000. ‘Representations of Development in 19th and 20th Century Indonesia: A

Transport History Perspective’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 36 (1): 185–207.

———. 2008. ‘The 2008 Shipping Law: Deregulation or Re-regulation?’. Bulletin of Indone-sian Economic Studies 44 (3): 383–406.

Esmara, Hendra. 1971. ‘An Economic Survey of West Sumatra’. Bulletin of Indonesian Eco-nomic Studies 7 (1): 32–55.

Gibson, Richard E. 1986. ‘Note: Selection and Evaluation of Small Scale Rural Infrastruc

-ture Projects’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 22 (1): 113–22.

Ginting, Meneth, and Ruth Daroesman. 1982. ‘An Economic Survey of North Sumatra’.

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 18 (3): 52–83.

Grey, Clive S. 1984. ‘The Jakarta Telephone Connection Charge and Financing Indone

-sian Telecommunications Development’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 20 (2): 139–50.

Henderson, J. Vernon, Ari Kuncoro, and Damhuri Nasution. 1996. ‘The Dynamics of

Jabotabek Development’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 32 (1): 75–95.

Hill, Hal. 1996. The Indonesian Economy since 1966: Southeast Asia’s Emerging Giant.

Cam-bridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hill, Hal, and Mubyarto. 1978. ‘Economic Change in Yogyakarta, 1970–76’. Bulletin of Indo-nesian Economic Studies 14 (1): 29–44.

Hughes, David E. 1986. ‘Note: The Prahu and Unrecorded Inter-island Trade’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 22 (2): 103–13.

Kong, Tao, and Arief Ramayandi. 2008. ‘Survey of Recent Developments’. Bulletin of Indo-nesian Economic Studies 44 (1): 7–32.

Kristov, Lorenzo. 1995. ‘The Price of Electricity in Indonesia’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 31 (3): 73–101.

Lee, Roy Chun, and Christopher Findlay. 2005. ‘Telecommunications Reform in Indonesia:

Achievements and Challenges’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 41 (3): 341–65.

Lindblad, J. Thomas, and Thee Kian Wie. 2007. ‘Survey of Recent Developments’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 43 (1): 7–33.

Magiera, Stephen. 2011. ‘Indonesia’s Investment Negative List: An Evaluation for Selected Service Sectors’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 47 (2): 195–219.

Mardjana, I. Ketut. 1995. ‘Ownership or Management Problems? A Case Study of Three Indonesian State Enterprises’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 31 (1): 73–107.

McCawley, Peter. 1970. ‘The Price of Electricity’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 6 (3): 61–86.

———. 1978. ‘Rural Electriication in Indonesia: Is it Time?’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 14 (2): 34–69.

———. 2010. ‘Infrastructure Policy in Indonesia: New Directions’. Journal of Indonesian Economy and Business 25 (1): 1–16.

Mears, Leon A. 1961. Rice Marketing in the Republic of Indonesia. Jakarta: PT Pembangunan.

Muir, Ross. 1991. ‘Survey of Recent Developments’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 27 (3): 3–27.

Munasinghe, Mohan. 1988. ‘Rural Electriication: International Experience and Policy in Indonesia’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 24 (2): 87–105.

Narjoko, Dionisius A., and Frank Jotzo. 2007. ‘Survey of Recent Developments’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 43 (2): 143–69.

Panglaykim, J., D. H. Penny, and Dahlan Thalib. 1968. ‘Survey of Recent Developments’.

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 4 (1) 1–34.

Partadireja, Ace. 1969. ‘An Economic Survey of Central Java’. Bulletin of Indonesian Eco-nomic Studies 5 (3): 29–46.

———. 1970. ‘Economic Survey of South Kalimantan’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Stud-ies 6 (2): 46–65.

Perkins, Frances. 1994. ‘Cost Effectiveness of Water Supply Technologies in Rural Indone

-sia: Evidence from Nusa Tenggara Barat’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 30 (2): 91–117.

Ray, David. 2003. ‘Survey of Recent Developments’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 39 (3): 245–70.

Soesastro, Hadi M., and Raymond Atje. 2005. ‘Survey of Recent Developments’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 41 (1): 5–34.

Soesastro, Hadi M., and Peter Drysdale. 1990. ‘Survey of Recent Developments’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 26 (3): 3–44.

Thee Kian Wie, and Siwage Dharma Negara. 2010. ‘Survey of Recent Developments’. Bul-letin of Indonesian Economic Studies 46 (3): 279–308.

Thompson, Graeme, and Richard C. Manning. 1974. ‘The World Bank in Indonesia’. Bul-letin of Indonesian Economic Studies 10 (2): 56–82.

Van der Eng, Pierre. 1993. ‘Survey of Recent Developments’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 29 (3): 3–35.

———. 1996. Agricultural Growth in Indonesia: Productivity Change and Policy Impact since

1880. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

———. 2010. ‘The Sources of Long-Term Economic Growth in Indonesia, 1880–2008’.

Explorations in Economic History 47 (1): 294–309.

Vermillion, Douglas L., S. R. Lengkong, and Sudar Dwi Atmanto. 2011. ‘Time for Innova

-tion in Indonesia’s Irriga-tion Sector’. Paper presented at the Ministry of Agriculture– ADB–OECD workshop on Sustainable Water Management for Food Security, Bogor, 13–15 December.

Wells, Louis T. 2007. ‘Private Power in Indonesia’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 43 (3): 341–63.

Wharton, Clifton, Jr. 1967. ‘The Infrastructure for Agricultural Growth’. In Agricultural Development and Economic Growth, edited by Herman Southworth and Bruce F. John -ston. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.