Vol. XXVI No. 12, December 2011 ISSN 0971-6378 (Print); 0973-2543

Magazine of Zoo Outreach Organisation

Magazine of Zoo Outreach Organisation

Vol. XXVI No. 12, December 2011 ISSN 0971-6378 (Print); 0973-2543 (Online)

‘Language and Technique’ for popular wildlife science (Extracts from a first person account of life and experience) Lala Aswini Kumar Singh, Pp. 1-3 Southern Purple-faced leaf Langur (Semnopithecus vetulus

vetulus) – a new colour morph Madura A. De Silva, Nadika C.

Hapuarachchi and P.A. Rohan Krishantha, Pp. 4-7

Project MOSI briefing notes (August 2011) An international zoo and wildlife park initiative to monitor the effects of climate change on mosquito species range spread, activity periods and behaviour, Pp. 8-12

Small Mammal Field Techniques Training, Thrissur, Kerala B.A. Daniel and P.O. Nameer, Pp. 13-15

Educator Training in Human Elephant Coexistence in Thailand, B.A. Daniel and R. Marimuthu, Pp. 16-17

British Conservationist, Belinda Stew art-Cox, awarded the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire OCB for outstanding service to conservation in Thailand, P. 18 Outings with Hoolock of Delo, Dr. Jikom Panor, Pp. 19-20

Announcements

The 1st International Gibbon Husbandry Conference, “The Great Lesser Ape, P. 21 National Level Hands-on Training Workshop on Principles and Practices of Animal Taxonomy, P. 23.

International Conference on Entomology, P. 29

National Conference on 'Biodiversity Assessment, Conservation and Utilization', P. 31

Technical articles

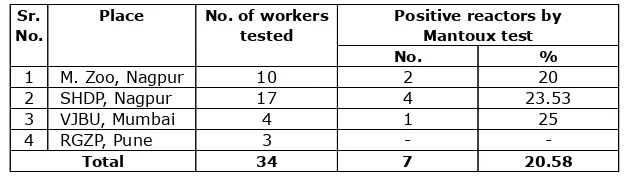

Estimation of Zoonotic Tuberculosis in Captive spotted Deer, S.D.Budhe, A.M.Rode, N.P.Dakshinkar, G.R.Bhojane and M.M.Pawade, Pp. 22-23

Chemo-Therapeutic management of foot abscess in female Asian Elephant (Elephas maximus), S.K. Tiwari and Deepak Kumar Kashyap, P. 24

Birds of Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary, Central India, Tharmalingam Ramesh, Natarajan Sridharan, Riddhika Kalle, Pp. 25-29 Hybanthus puberulus M. Gilbert. (Violaceae) – A new record for India, Sasi, R., Sivalingam, R. and A. Rajendran, Pp. 30-31

Contents

Southern Purple-faced leaf Langur - a new colour morph, See Pp. 4-7 A mini drama performance on rescuing elephants,See Pp. 16-17

Simple tools and easy interpretations can help a lot for popularizing science, particularly when it is in the kind that is off the main academics. Here are a few experiences, innovations and lessons under Crocodile Conservation Scheme and Project Tiger which are two nation-wide projects for scientific management of wildlife resource.

Field practices in these projects have largely been successful as the science of Wildlife Conservation has been explained and implemented with appropriate range of field-languages and techniques suitable for various levels. It has been done with (a) the staffs at the grass root level who strive to translate theoretical recommendations into field actions, (b) the local people who understand just the simple ways of the nature that has nurtured their character to use and protect the resources for generations, and (c) the students who wish that the Wildlife Science steers them through a meaningful career (d) The remaining public at large and the media are reached with the entire package of approaches.

Wildlife Management prescriptions are strongly directed and improved from experience and lessons learnt in the field. At least three other components which keep changing and interacting on each other also determine the course of management activities. These components are the (a) ecological factors influencing the habitat of wildlife species, (b) the changing or adaptive behaviour of wildlife species, and (c) eco-friendly accommodation of the demand and expectations of various anthropogenic elements. All these components have shaped the growth of the science of wildlife management.

Of late I fear, to a certain extent ‘Wildlife Management Practices’ is digressing away from the realities of requirements in the field. Instead of laying emphasis on indigenous innovations Wildlife Studies and Management are getting studded with experiments and recommendations applicable to wildlife from very different biomes in other parts of the globe. As a result, perhaps the Wildlife Science is heading to become an abstract science that is not a true refection of Indian natural history or wildlife biology. There is an increasing trend for applying techniques that appear to overshadow the management of ‘wild living beings’. Modern gadgets and statistical extrapolations should be used for improving interpretations and not as a matter of

convenience to replace field rigours. It is misleading and dangerous to get satisfied with answers to everything out of very little field data.

One of the many reasons for this trend is rooted to a kind of infatuation reflected through dependency and over-use of virtual mathematical models. Computers and remote sensors are able to provide choice for studies without hazardous field camping. Another reason is the

administrative and financial ease for experimenting in the field such costly products which are results out of scientific and industrial growth in the electronic sectors. These are fine as supplements that are short-lived enthusiasm for adding luster. These shouldn’t sacrifice the most

established and familiar basics in natural history and wildlife biology.

A popular subject easily elicits public cooperation In 1952 the ‘Central Board for Wildlife’ was constituted as conservation of wildlife is an important, popular and widely advocated subject of importance for human survival. Later, the Board was renamed as the Indian Board for Wildlife

with parallel Boards at the State level. The members of the Board are drawn from a wide range of public and

professional profile. These members need to be told in simple terms what is all happening in the wildlife sector.

In accordance with recommendations of the Board we have celebration of the Wildlife Week, coinciding with the birthday of Mahatma Gandhi. At this time there are publicity through lectures, print and electronic media, film shows, guided nature tours, and essay competitions in schools and colleges. Other activities that popularise and educate different target groups about the Wildlife Science are ‘nature clubs’ in educational institutions, and the subject of environmental conservation in the syllabus adopted by the NCERT (National Council of Education Research and Training). The University Grants Commission (UGC) recommended for setting up of faculties on wildlife education in selected universities but the curriculum appears to have only a few takers. The North Orissa University runs a self-financing M.Sc., course in Wildlife Conservation and Management.

School students are the most receptive to conservation message

During 1994-1997 we started to conduct a number of 3-days long nature camps in Similipal Tiger Reserve. There were different participant groups,--- the undergraduate students, college faculties, members from the civil society with various professional profiles, and the school students. The purpose was to give a type of once-in-lifetime exposure in the forest, and demonstrate the various wildlife

conservation tools and techniques including studying of tracks and signs. The significant lesson for the

management was that the High School children constituted the best target group as these were receptive as well as meaningfully responsive.

The language of interaction and the curriculum of a nature camp were very carefully drawn up. Every part of their time during trekking or discussion gave the participants guided orientation and information. The forest guards, foresters, range officers and watchers were very enthusiastic during those days when they could share their life and experience in the forest with wildlife. The language for communication of the art and science of wildlife conservation was simple, interesting and adventurous for the staff and their audience. I have seen, some of the children (students) becoming emotional before the staff when it was time for departure from the forest.

Successful conservation and research go hand-in-hand

‘Successful conservation and research go hand in hand’. That was the dictum of approach in crocodile conservation programme launched in 1974-75, and it showed the approach for other wildlife conservation projects. There were two main conservation projects in India during 1970s and 1980s. The approach for handling research was different in the beginning. Fresh pass outs from Universities were selected for crocodile conservation work. But in Tiger Reserves the Field Directors handled research initially. Later, Research Officers worked under concerned Protected Area managers or the Chief Wildlife Wardens.

‘Language and Technique’ for popular wildlife science

(Extracts from a first person account of life and experience)Lala Aswini Kumar Singh*

The scientific personnel involved in crocodile conservation programme, project tiger and other wildlife conservation activities in situ and ex situ have produced the bulk of information and literature available today about the target species and the activities for conservation and

management. Administration has come to recognize that research personnel form the assured base for access to information. Most often these research persons carry out most of the interpretation work for a project. Special Projects like that for vulture breeding is awaiting a suitable research person to remain in charge of it.

Grooming authors who work and write

My professor from University days, Professor B. K. Behura says research is incomplete without a publication. Yes, unless observations are published, a new researcher joining at some later stage wastes days or years in rediscovering what is already known. At this stage come the aspects like authorship of an article or a research paper, and the choice for a journal.

Considering the actual role of a researcher and the need for sustainability of the pursuit for popularization of scientific research, authorship has to be given due consideration. Administrators or technocrats who adorn chairs for supervision need to be open hearted in giving credit. A scientist often works just for the shake of recognition!

I was recently writing my reaction in response to a blog about the not very happy experience for authorship status like first, second, third, etc. in a publication. The contention is about who will be the first author, and what order should be followed upto the last author. In scientific laboratories some kind of understanding seems to have prevailed. This is not true in non-research organisations, where the principal or prime researcher normally brings into his fold of confidence as many ‘authors’ as possible. At the end the authorship credit may appear to be a hierarchical testament under the title of the paper.

When it is a management prescription it is, however, a good idea to have that kind of authorship. People who matter get encouraged and also implement its advantages.

Nevertheless, I have also noticed that although I have many coauthors during the course of my 36 years of research, very seldom have they produced a technical publication even in their next posting. I have a notion that publication potential is everywhere and in every posting of a person.

During Post-Graduation it was training and, therefore, customary to follow the hierarchy or age-seniority in a research paper. I have taken the facts in that spirit. Things were different after M.Sc. In this context I must pay my tribute to one person– Dr H. R. Bustard, the FAO Consultant in India for Crocodile Conservation programme. The project started during 1970s, and there I started my professional career. Dr Bustard was the field guide and non-official Ph.D. guide for me. He had issued a circular very early about the principle to be followed for authorship of technical papers. If it was equal contribution starting from an idea to experimentation or data collection and writing, the authorship was alphabetical, though Dr. Bustard had the alphabetical advantage over me. For other instances, depending on contributions the first authorship was shared among us.

That was a very healthy practice. Other co-researchers were also happy with that. It got flouted when I had to write with (for) others. Yet, I always expected, sometime somewhere somebody should bring my name to the first, or while giving a talk or powerpoint presentation at least used a ‘plural term’ to indicate that the analysis was done with

others in the administrative set up. Very seldom did it happen, if it ever did. That sometimes hurts a field researcher, and it dampens the spirit of continuing the pursuit of writing for popularization of science!

Where should I publish my work!

The year of start, the international stature of the wildlife project and the locations for my field work were such that most of the observations were new and worth reporting or publishing. Out of over 250 write ups by me only about a dozen may be overseas publications. Others are in Indian journals but with overseas circulation. I always exercised my own choice and option for a journal. I have chosen the journal in such a way that the publication reaches the right audience or the right user.

When I am writing about a new technique which field foresters are to use, I choose Indian Forester which reaches all Divisional Forest offices of India and many desks

overseas. When it is a biological note on an Indian species I have chosen the Journal of Bombay Natural History or Hornbill. When the observations or discussions have implications in captive management of animals in India I chose the Zoos’ Print. A very old time journal is Cheetal published by the Wildlife Preservation Society of India, Dehradun. These are very widely circulated and established journals for wildlife matter. The WWF Newsletters, the IUCN Specialist Group Newsletters and Sanctuary-Asia are some of the other publications for submitting write ups.

In those days, there was no ‘impact factor’ of a journal, and there was nothing like internet to browse and search. I had to build my own library. For the last four decades I have been carrying bulks of paper wherever I went. I came to know about impact factor when my daughter started publishing her work on nano medicines and discuss with me issues relating to it while selecting a journal for submission of papers. In modern days the ‘impact factors’ seem to be the basis for judging the scientific status of a scientist.

Inspired, I searched the net for any possible impact factor given to my journals, but no. My journals, although very special in their kind and used by field workers, had nothing like an impact factor. I am not aware, what exactly is the situation today. I cannot comment on medical science research, which has global implications. And the trend is changing in the world of research.

What I drive to say is that present-day wildlife scientists are competing to gather ‘impact factors’ through publication of their data overseas, but its utility is often lost to actual field level users. Therefore, where field research involves natural history or techniques for sanctuary management, one must not worry where the journal is published or what is it’s impact factor; but must think whether the contents of the writing reaches the field staff and field biologist who will benefit from this and shall not spend time in rediscovering what has already been discovered. They should instead carry the work ahead from the point where it is left at that moment. In this respect there should be a mention about the open access journals on the internet these days. These are very good, very quick, available on the net, and perhaps with some impact factors, if someone is bothered about it.

Field-translation of professional lessons from ingenous masters

As a fresher in wildlife research I had the first opportunity to listen to Saroj Raj Choudhury when he explained near a stream along Tikarpada-Purunakote road on how to interpret hooves marks indicating stampede behaviour of a herd of spotted deer. The herd might have heard or sighted a predator, perhaps the tiger. Through that, Choudhury was giving the basic guidance on how a practitioner of wildlife research should remain alert for visual signs as well as smell and sound to make his field studies fruitful and safe.

During my work in the Mahanadi I had nearly six and a half years of field work with the help of Raja Behera and the team comprising his nephew Prafulla and son Amulya. All three were engaged as Gharial Guards at Tikarpada, as a strategy towards demonstrating ‘people’s involvement in crocodile conservation. Many other experienced persons like Narottam and Shiba joined as Gharial Guards later. All of them were boatmen and fishermen by profession. They were able to negotiate their narrow long wooden boat on the waters of Mahanadi along the downstream or upstream or in high flood with as much ease and comfort as they did it during low waters of winter and summer. I had my first lessons of rowing a boat from Prafulla and Amulya.

More important, from Raja and others I also learnt how to spot and confirm the sighting of a crocodile on water surface or on sand banks. Then, there were training sessions by Dr. Bustard on how to eye-estimate the length of crocodiles from a distance.

Those were initiations which kept me water-borne and study crocodiles. Rest of the happenings in my career

demonstrated that indeed ‘necessity is the mother of invention’. I wanted to judge the size of the crocodile from just the portion of the head that remained surfacing on water or the various kinds of tale telling spoors of a crocodile that had basked on sand banks. Then I devised the methods for size estimation from body spoor. Similarly, was the invention of the technique to individually identify hundreds of crocodiles from their tail-scute colour pattern. These are simple field techniques that keep the science accessible, usable and popular.

Field techniques have to be comprehensible in implementation and interpretation

One of the major scientific activities in wildlife management is census of wildlife species, at least a few indicator or flagship species, which can indicate the condition or happenings in the entire habitat. The results of census attract the attention of the public, media and the concerned administration. Census results form an easy and direct access to the story of performance of the project on species conservation.

Observing wildlife in natural conditions is not easy because wild animals have learnt to avoid threats or disturbances. That is their strategy and adaptation for survival. The task is more difficult when ground vegetation is dense and high. Determining the exact numbers of wild animals is a difficult technical requirement but has to be carried out with man power available within the Forest Department. By

conducting the census the staffs get a first hand feel of the status of the animals inhabiting their jurisdiction, and have a sense of belongingness. Therefore, the technique has to be staff-friendly, something which they can understand, implement and interpret.

For every occasion of wildlife census in Similipal, about 25 participants from different parts of the state and a few from other states and even overseas join the staffs as non-official volunteers. They all belong to very different walks of life. They are given orientation training about the method of census and the jungle-etiquettes. They live with Forest Guards or watchers in tree-top machans or Beat-Camps and carry out field work during the entire period of census. Again, some of them come back for analysis and interpretation of data, and drawing of spatial distribution map of the species counted. For tiger and leopard they become conversant in pugmark tracking method and for elephants it is direct sighting.

A few of these participants have chanced into my office after several years and interacted with me. In these years some of them have reached new heights of career excellence but they continue to be passionate as before. They have expressed that the visit they had to Similipal has left a permanent impression in their mind and action. I feel that the level of interactions with them and the quality of data they handled were responsible for such lasting memory. The Science of Wildlife Conservation has to be easy and understandable through simple biological explanations and the application of common logics.

Some lessons and guidelines

There is no shortcut in Wildlife Science. It has to be backed with full quota of rigorous field exercises carried out locally in the heat or frost, soiled knees or knee-deep humus. While popularising Wildlife Science some of the lessons learnt and that may form recommended guidelines are as follows.

• The staffs of the wildlife organization who implement the project in the field must feel themselves a part of the science that is in practice, and should be able to take pride in explaining the subject and the related activities hey are doing. These staffs include grass root level persons like the Forest Guards as well as Research Scholars who join with career ambitions.

• The people who live within the forest or its fringe who have already contributed a great deal of traditional knowledge, should be comfortable with the new tools and participate in various management actions directly or indirectly, with a sense of belongingness.

• The spectra of administrators, intelligentsia in the society, public representatives, media persons and other stake-holding organizations, who too play a substantial role in sustenance of pursuits linked with ‘Wildlife Science’ must understand the language of the science and be able to convincingly explain these to others in apropos of their own activities.

At one point in time, the Purple-faced leaf Langur had been placed in the genus Trachypithecus but after molecular analysis (Karanth et al.

2008) it was placed in genus

Semnopithecus. Trachypithecus now belongs to the genus Semnopithecus.

Trachypithecus corresponds to leaf langurs of South East Asia. There are four subspecies inhabiting four distinct localities. They are Southern purple-faced leaf Langur Semnopithecus vetulus vetulus (Erxleben 1777) Montain purple-faced leaf Langur

Semnopithecus vetulus monticola

(Kelaart, 1850)

Western purple-faced leaf Langur

Semnopithecus vetulus nestor

(Bennett, 1833)

Northern purple-faced leaf Langur

Semnopithecus vetulus philbricki

(Phillips, 1927)

The taxonomy of Purple-faced leaf Langur has been confusing as it was never given an accurate to thorough molecular scrutiny which led to many modifications in generic names. Karanth et al. (2008) solved the problem by sequencing and analyzing the genetic features from a variety of leaf monkey species. This work supports clustering of Nilgiri and Purple-faced Langur with Hanuman Langur. Leaf Langurs

(Trachypithecus) form a unique clade and phylogenetic studies indicate both Purple-faced leaf Langur and Hanuman Langur belong to Genus

Semnopithecus. Their taxonomy will be further distinguished by genetic studies within the recognized

subspecies and geographical variations in both Hanuman and Leaf Langurs.

Semnopithecus vetulus vetulus (Erxleben, 1777)

Size moderately large, head and body about 494-542mm; tail length range 691-734mm, weight 5.5-9kg. Small, rounded head; short, narrow neck; small round and flat ears standing out from head (Phillip 1935). Body and limbs black with rid brown tint and mid-dorsal area slightly frosted white; lower back and sacral region with triangular silver-white rump-patch, sharply defined margins, extending down the tail and sides on thighs down to knees in some instances. Whiskers white or off-white, brownish at tips; throat pure white and hairs about the mouth also white; under-parts black; tail silvery-white on two or three inches adjacent to the sacral patch, the remainder mole-grey, sometimes

becoming reddish-brown towards the tip. Naked parts of the face, hands, feet pure black, eyes with golden brown iris (Phillip 1935). Among the National Museum primate specimen collection a pale coloured had catalog number 4G 20.11.1923, collected by W.W Philips from Matara District indicating colour diversity among Southern Purple-faced leaf Langur even in early 1900’s.

Southern purple-faced leaf Langurs inhabits both thick jungles and wooded home gardens. Observations made by the research team found the number of individuals in forest troops is lower than the number of individuals found in home gardens. The number of

individuals per troop may vary from four to eighteen, living in treetops, descending to ground occasionally to get fallen fruit or to get to trees beyond their movement range. They carry their tails hanging down, instead of over their backs like Grey Langur. Each troop has a favorite range and stays there mostly.

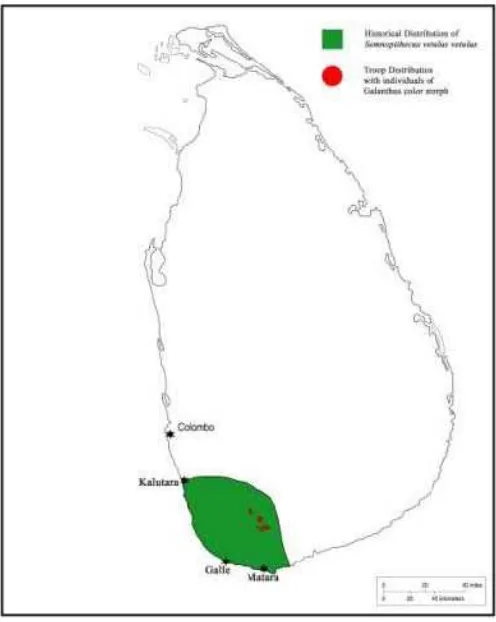

It has been recorded south of Kalu River to Ranna by Phillips (1935). Its upper inland limits are restricted to nearly 1,000m from sea level. It has been recorded at Akurassa,

Kekunadura, Welihena, Dandeniya, Wattahena, Polgahaivalakande, Krindi Mahayayakele, Kalubowitigana, Deniyaya, Diyadawa, Dediyagala, Kanumulderiya, Matara, Weligama, Pitabeddara, and Gongala (Matara

Dist); Wakwella, Rumassala,

Baddegama, Unawatuna, Galle Fort, Richmond Hill, Udugama,

Yakkalamulla, Galle, Hiyare, Alpitiya, Ambalangoda, Hikkaduwa, Pitigala, Sinharaja, Kanneiya, Kottawa, Lankagama, and Habraduwa, (Galle district); Masmullah, Matugama, and Anasigalla (Kalutara district); Bambarabotuwa, Delgoda, Delwala, Denihena, Weddagala, Walankanda, Kudawa, Rakwana, Morahela, Hadapan Ella, Suriyakande, Ratnapura,

Kribatgala, and Samanala Wewa (Ratnapura district) (Philips 1935; WCSG 2010). (Map 1)

The WCS Galle primate research team carried out research on distribution, feeding ecology and behaviour of Southern Purple-faced leaf Langur since 2007. This included tracking and recording distribution using GPS locations, feeding behaviour, food selection and social interactions of the troops. We observed 26 troops from rainforests and home gardens in Galle and Matara Districts during the study. Our team observed more than 30 primates with unusual white colour morph in 14 troops. During the research all troops were given a troop number (e.g. T7) and all individuals were given an ID consistent with the troop number including a unique number to identify each individual

Southern Purple-faced leaf Langur (

Semnopithecus vetulus

vetulus

) – a new colour morph

Madura A. De Silva, Nadika C. Hapuarachchi and P.A. Rohan Krishantha

Wildlife Conservation Society – Galle Biodiversity Research and Education Centre, Hiyare Reservoir, Hiyare, Galle Sri Lanka. Email: hapuoo7@yahoo.com

Fig. 1 Semnopithecus vetulus vetulus Black colour morph

within the troop (e.g. T5I7 is the seventh individual of fifth troop). There is no evidence to suggest full albinism of Galanthus (Etymology: Named for its white body colour, Galanthus = Snow white) forms due to following reasons: - All white individuals had black naked parts of the face. - None of the white individuals had red eyes.

- All of the white individuals had beige to ashy brown crown hair.

- T4 troop had a white coloured alpha male.

- Face of T3I1 showing the black naked part of the face and the eyes.

Individuals with Galanthus colour morph were observed among 14 troops mainly from rain forest and rain forest associated habitats. The maximum ratio of individuals of the Galanthus morph to the normal morph was 4:6 (Troop ID: T4). This includes adults, juveniles and infants of both sexes. The alpha male of the troop T4 was a Galanthus male. (Fig.4 and 5)

Galanthus colour morph

Body and limbs white, sometimes with ashy patches, whiskers white or off-white, throat pure white and hairs about the mouth also white; under-parts pinkish to

yellowish white, tail white. Naked parts of the face and ears black, hands and feet pinkish yellow with black patches. Eyes with golden brown iris and beige to ashy brown crown hair.

The number of individuals with a white coloured coat is extraordinary. This can be an indication of the

difference between the rain forest troops and the surrounding non-rainforest troops of Purple-faced leaf Langurs. Determination of genetic or taxonomic differences among the sub-species of these Langurs requires molecular and morphological studies, which the primate research team of WCSG is hoping to carry out in the feature.

Conservation Issues

Globally a third to half of all primate species are threatened due to habitat destruction and over-exploitation (Mulu 2010). Developments in agriculture and irrigational strategies, along with an increase in human settlements, have caused damage to areas of Sri Lankan rainforest for decades (Erdelen 1988). Consequently, much of the rainforest is fragmented and troops that inhabit home ranges bordering human districts inevitably exploit agricultural land for food sources. Conflict in Southern areas may alter perceptions of the Purple-faced leaf Langur, currently considered as a pest in the more populated Western province, where it is the most common primate (Dela 2007; Rudran 2007) Semnopithecus vetulus vetulus

inhabit the same space with humans in periurban and rural areas. They struggle to survive on stolen garden fruits and tree leaves in and surrounding homes.

Many trees are removed as villages enlarge gardens and larger cultivated areas are expanded. This leave many open areas that have to be crossed over, and the Langurs in that area are highly vulnerable. They then have to travel on the ground or on telephone and electrical wires, both options are often deadly; they are killed by dogs, traffic accident and electrocution (Fig. 7). However, most Sri Lankans are often tolerant owing to religious and cultural beliefs, which respect other forms of life, leaving habitat loss as the most fundamental threat. Although habitat loss is manageable, when whole forests are removed, the species in that habitat will not survive. Fragmentation occurs when forested areas are divided for plantations, Map 1. Distribution of troops having the

Galanthus colour morphs

roads, industry or urban expansion. Some individuals will be lost and some will survive in smaller areas but separate from their relatives. Individuals with Galanthus colour morph were mainly observed among the troops inside rain forest and rain forest associated habitats. Most of these rain forests are adjoining to commercial lowland tea plantations and tea small holders, therefore a major issue related to the Galanthus colour morph is encroachment of rain forest by tea cultivations.

Conservation Measures

Although the Purple-faced leaf Langur is protected by Sri Lankan law and categorized as Endangered by IUCN (IUCN Red List 2011) it faces uncertain

future if national policies are not actively implemented to ensure the species is protected. Policies and institutions need to ensure protection by fines, research, co-operation with urban planning and strict borders to reserves with surveillance. Forests, wildlife, environment, agriculture, and urban planning all fall into different ministries that rarely cross reference issues of preservation and protection of flora and fauna. Qualitative and quantitative data on existing species is needed for the whole island.

Systematic DNA testing is needed to determine subspecies and form accurate maps of locations and where groups are isolated and gene pools are narrowed. Individual numbers, breeding records, and mortality rate will help determine how stable the populations are and where the greatest efforts are needed to ensure

preservation.

Workshops and regional cooperation will help highlight issues to the general

public and create awareness. The striking white color morph will also hopefully provide an iconic image for the reinforcement of the current conservational strategies employed, heightening awareness of the vast number of endemics on the island. Village schools need programs to highlight the dangers of removing forests and importance of biodiversity. Sri Lanka has very high biodiversity within the global picture and this is something people need to be proud of in order to protect and keep their rank as one of the most special places on earth.

Education programmes for schools children and general public Five education programmes were organized for school children and public, highlighting the importance of the Southern purple-faced leaf Monkey. Local schools, farmers and public were encouraged to plant the food plants of the monkey (Fig. 6). The role of these primates on pollination and seed dispersal were explained to them.

Bibliography

Bernede, L & K.A.I. Nekaris (2004). Population densities of primates in a regenerating rainforest in Galle

District, Sri Lanka. Folia Primatologica. 75: 235-236.

Brandon-Jones, D. (2004). A Taxonomic revision of the Langurs and leaf Monkeys (Primates: Colobinae) of South Asia. Zoo’s Print Journal 19(8): 1552-1594.

Corbet, G.B & J.E Hill (1992). The Mammals of Indomalayan Region. A systematic review. Oxford University Press. Oxford.

Dela, J & N. Rowe (2006). Western purple faced langur Semnopithecus vetulus nestor Bennett, 1833. In: Mittermeier et al., (compilers) Primates in peril: The world’s 25 most

endangered primates, 2004–2006, pp. 12–13, 24. Primate Conservation. (20): 1–28.

Dela, J. and N. Rowe. 2007. Western purple-faced langur, Semnopithecus vetulus nestor Bennett, 1833. In:

Primates in Peril: The World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2006 – 2008, R. A. Mittermeier et al. (compilers), pp. 15, 28. Primate Conservation (22): 1 – 40.

Deraniyagala, P.E.P (1955). A new race of leaf Monkey from Ceylon.

Spolia Zeylanica. 28: 113-114. Dittus, W., S. Molur & K.A.I. Nekaris (2008). Trachypithecus vetulus ssp. vetulus. In: IUCN 2009. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2009.1.<www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 13 October 2009. Dittus, W., S. Molur & K.A.I. Nekaris (2008). Trachypithecus vetulus. In: IUCN 2008. 2008 IUCN Fig. 6 School children engaged in plantation

Red List of Threatened Species. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 18 November 2008.

Dittus, W., S. Molur & A. Nekaris, (2008). Trachypithecus vetulus ssp.

vetulus. In: IUCN 2011. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. <www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 31 August 2011.

Douglas, P.H., R.S. Moore, S. Wimalasuriya, A. Gunawardene & K.A.I. Nekaris (2007). Microhabitat variables influencing abundance and distribution of diurnal primates (T. vetulus vetulus and Macaca sinica aurifrons) in a fragmented rainforest network in Southern Sri Lanka. European Federation of Primatology, Prague. Folia Primatologica 2008. 79 (5): 324-325.

Erdelen, W. (1988). Forest

ecosystems and nature conservation in Sri Lanka. Biol. Conserv. 43: 115–135. Eschmann, C., P.H. Douglas, L.P. Birkett, A. Gunawardene & K.A.I. Nekaris (2007). A comparison of calling patterns of purple-faced leaf monkeys (Trachypithecus vetulus vetulus and T. nestor) in Sri Lanka’s Wet Zone. European Federation of Primatology, Prague, p 19. Folia Primatologica 2008. 79(5): 326-327.

Eschmann, C., R. Moore & K.A.I. Nekaris (2008). Calling patterns of Western purple-faced Langurs (Mammalia: Primates:

Cercopithecidea: Trachypithecus vetulus nestor) in a severely degraded human landscape in Sri Lanka.

Contributions to Zoology 77(2): 57-65. Hill, W.C.O. (1934) A monograph on the purple-faced leaf monkeys (Pithecus vetulus). Ceylon Journal of Science (Spolia Zeylanica) 19(1): 23 – 88.

Hinton, M.A.C. (1923). The nomenclature and subspecies of the Purple-faced Langur. Annals. Magazine of Natural History. 11: 506-515. Karanth, K.P., L. Singh, R.V. Collura & C. Stewart (2008). Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of langurs & leaf monkeys of South Asia

(Primates: Colobinae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution .46: 683– 694.

Kelaart, E.F. (1850). List of Mammalia observed or collected in Ceylon. Journal Ceylon Branch, Asiatic. Society. 2: 203-207.

Mulu, K.S. (2010). Are the endemic and endangered Tana River primates culprits of crop raiding? Evaluating Human – Nonhuman primate conflict

status around Tana River Primate Reserve, in Kenya. Institute of Primate Research, Nairobi, Kenya.

Phillips, W.W.A. (1980). Manual of the Mammals of Sri Lanka. 2nd Revised Edition, Wildlife and Nature

Protection Society of Sri Lanka, Colombo, Sri Lanka. pp. 117–127. Phillips, W.W.A. (1935). Manual of the mammals of Ceylon. Colombo Museum, Ceylon. 373pp.

Phillips, W.W.A. (1927) A new

Pithecus monkey from Ceylon. Spolia Zeylanica. 8(14):57-59.

Rudran, R. 2007. A survey of Sri Lanka’s endangered and endemic western purple-faced langur (Trachypithecus vetulas nestor).

Primate Conserv. (22): 139–144.

Note:

This is a project report of primate research team, biodiversity research and education centre, Wildlife Conservation Society Galle (WCSG), carried out in the rain forests of southwestern Sri Lanka with the financial support of Nations Trust Bank.

Photo credits: Nadika Hapuarachchi, Rohan Krishantha, Krishan Wewalwala and Karen Conniff

Introducing Project MOSI

In October 2010 the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA) and the Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (IZW), in concert with the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and Imperial College, agreed to develop a permanent international mosquito monitoring programme -Project MOSI (Mosquito Onset Surveillance Initiative). Utilising the unique monitoring potential of the world’s zoo and wildlife park networks, the core remit of this initiative is to monitor the effects of climate change on mosquito species range shift, activity periods and behaviour. Good progress has been made establishing new monitoring sites and, over the next 18 months, the programme aims to involve up to 60 zoos, wildlife parks and associated institutions around the world. Background information, involvement rationale and associated details are provided below.

The importance of studying mosquitoes

A large number of mosquito species are principle vectors of a wide range of vector-borne diseases (human and avian malaria, dengue, West Nile encephalitis, elephantiasis and so on). All blood-feeding mosquito species use chemicals produced by their vertebrate host to locate them in order to have a blood meal essential for egg production. This “cocktail” of attractive odors produced by the host varies greatly from host species to host species and mosquitoes can be more or less attracted to them depending on their feeding preference (mosquito species can be mammophilic if they’re attracted by mammals; ornithophilic if attracted by birds; batracophilic when attracted by amphibians and so on).

In addition to its intrinsic biodiversity information value, monitoring mosquito species distribution, population abundance, activity periods and behavior (host preference, feeding and oviposition etc.) is essential for better

protection of human and wildlife communities. Human, wildlife and disease vector communities establish an equilibrium over centuries of association. What might

happen when vector species and their associated

transmittable diseases experience more favorable conditions and are introduced or spread to new areas? To detect, study and effectively respond to such developments ongoing monitoring is vital.

Mosquitoes in a changing world

Human activities have long influenced the distribution and behaviour of many mosquito species. Historically, this has largely been due to a combination of habitat alteration and the movement of goods and people. In addition to these ongoing influences, global warming has emerged as an important contributory factor that, on current trends, is set to become increasingly significant in lengthening activity periods and creating new colonisation opportunities with potentially serious human and wildlife health implications. The Asian tiger mosquito Aedes albopictus is a good example of a species having its range greatly extended as a result of human activities. This forest-living, dendrophilic species (laying eggs in water-filled tree-holes) has spread around the world (predominately via used tyres and the tropical plant trade). It has established itself in cities where elevated temperatures and humidity and artificial water pools, combined with little or no predation or competition, have enabled it to thrive.

The tiger mosquito can transmit a number of pathogens such as, the West Nile Virus, Yellow fever virus, St. Louis Encephalitis, Dengue fever, and Chikungunya fever. Higher temperatures also allow parasites and diseases to live longer and consequently become more likely to complete their life-cycles (and transmission ability) even in previously inhospitable northern and high elevation regions. The 2007 Chikungunya fever outbreak in Italy demonstrates that the introduction of vector species, such as the tiger mosquito, can be followed by their associated transmissible diseases.

Another example is provided by Anopheles plumbeus. This dendrophilic European species has adapted to breed in a range of artificial breeding sites and as a consequence has

Project MOSI briefing notes (August 2011)

An international zoo and wildlife park initiative to monitor the effects of climate change on mosquito species range spread, activity periods and behaviour

greatly increased in numbers and area over the last few decades (Becker, 2003). Due to its aggressive biting behaviour and population increase, this mosquito has become a significant nuisance. Although endemic malaria has disappeared from Germany, travellers import

approximately 1000 registered cases of malaria every year over the last decade. Two cases of autochthonous

Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Germany with evidence for local transmission by indigenous Anopheles plumbeus

were recorded in 2001 (Krüger, 2001).

Zoos and wildlife parks as valuable monitoring stations

Zoos provide unique mosquito monitoring environments with large numbers of exotic host species, micro-habitats and shelters suitable for breeding and overwintering. Such situations provide an incomparable opportunity to study the behavior of mosquitoes offered with multiple choices of hosts and environments.

Exotic species in a zoo environment are exposed to local indigenous fauna, their vectors and diseases. Zoo animals are routinely screened for any sign of illness and new acquisitions are quarantined and monitored. This means that infection routes are invariably from local wild fauna to zoo animals. This makes zoos uniquely valuable local, regional and international health surveillance sites, providing advance warning to wildlife parks and human settlements of non-native mosquito’s species introductions, population explosions and behavioral changes. Indeed, there is a significant history of valuable zoo based mosquito study and associated monitoring.

Wildlife parks provide remote monitoring areas that without such a surveillance programme would be unlikely to be regularly (if at all) monitored for mosquito species composition and activity patterns. This data can be very valuable for health management of the species in the parks and for nearby human settlements, again, providing advance warning of non-native mosquito species introductions, population explosions and behavioral changes.

The combined regional and global-scale monitoring potential of zoos, wildlife parks and their associated institutions is clearly tremendous. Utilising this potential is key to enabling any initiative of the scale of project MOSI to succeed. This programme will also greatly benefit other mosquito recording schemes and control endeavors.

Principle objectives of Project MOSI

1. Establish an international network of 60 permanent mosquito monitoring sites.

2. Confirm baseline species composition, abundance and activity profiles.

3. Continually monitor for changes in species composition, abundance & activity profiles.

4. Help clarify the impact of climate change on a large number of mosquito species.

5. Provide an early warning network for detecting movement of disease vector species.

6. Help efforts to evaluate and better control mosquito vector disease threats.

7. Help develop improved mosquito attractants and trapping methods.

Pilot study summary

From 2005 onwards, monitoring of mosquito populations at ZSL London Zoo, in collaboration with Imperial College, has been undertaken by mosquito specialist Giovanni

Quintavalle Pastorino with a focus on species composition, population abundance and seasonal activity profiles. Different trapping methods have been tested (resting boxes, mosquito Magnet traps, ovitraps, gravid traps and Biogents Mosquitaire traps) to determine their relative suitability. This has provided sufficient confidence for the cheap and easy to maintain Biogent Mosquitaire traps to be utilised as the standard monitoring trap for Project MOSI.

Comparative trials (including the efficacy of different attractants) are continuing as part of the Project MOSI initiative and Giovanni is providing the specialist support role of specimen identification, training and generation of technical reports for the full programme.

What participating institutions derive from joining the programme

• An additional practical measure to help protect sensitive species.

• Monthly up-date on species composition and population abundance via free identification of the collected samples posted to ZSL.

• Real time feed-back on seasonal mosquito activity – enhancing possibility of rapid intervention to reduce population growth (using BTI larvicides for example). • Integration of data from other surveillance sites to

monitor regional and global changes in species

distributions and behaviour with opportunities for advance warning of species range shifts and potential deeper investigation (at request of institution’s veterinary department) of local mosquito-vector disease cycles. • A comprehensive annual report.

• At the discretion of each participating institution, site-specific data can be either incorporated into wider research findings and collaborative publications or kept confidential.

• At institution’s discretion, support with undertaking the specimen identification role in-house.

• A novel and engaging opportunity for an institution to convey the practical significance of climate change and wider human impacts on disease vector species.

What’s required of participating institutions.

• Placement of a Biogents Mosquitaire mosquito trap in an appropriate site location (In zoos this is often near a bird enclosure or any other animal considered sensitive to

mosquito bites that would benefit from the added protection a trap provides). • Weekly collection of

mosquitoes trapped in the Mosquitaire and storage in a normal fridge (at around 4°C).

• Monthly postage of the collected specimens to ZSL in a labelled plastic tube with the date of collection and trap number.

Safety assurances

Some assurances to allay any public relations concerns associated with a zoo or wildlife park participating in the monitoring programme:

• Due to the wide range of potential host species, a zoo or wildlife park environment are among the least likely outside environments for people to be bitten by mosquitoes.

• The majority of mosquito species are active at times when these facilities are normally closed but in any case having mosquito traps on site reduces the incidence of being pestered by mosquitoes.

• The majority of mosquito borne diseases that might present in a zoo or wildlife park are non-human related. • Mosquitoes found in the grounds of a zoo or wildlife park

are invariably indicative of a wider local/regional

presence. By establishing mosquito monitoring initiatives zoos and wildlife parks provide a valuable surveillance service for the local community and for the region’s effective wildlife health management.

• Participating in such initiatives constitutes an additional practical measure to protect our animals and local communities.

Costs and staff time involved in participating in the monitoring programme

Other than the electricity cost of running the trap and monthly postage of specimens to ZSL the only notable costs involved in participating is the initial outlay for the Biogents Mosquitaire trap (approx €150), and replacement

‘sweetscent’ attractants (approx €210 a year per trap). The replacement attractant packs include spare trap nets at no additional cost. For a single trap, staff time involved in trap maintenance and specimen processing averages around 30 minutes a week.

Biogents Mosquitaire trap near zoo enclosure

Removable capture net at base of trap funnel

Sharing information

As this permanent monitoring initiative will increasingly be filling significant knowledge gaps on mosquito species range status, activity and behaviour changes, an ongoing remit is to ensure that annual reports and significant developments are communicated to relevant organisations and agencies. These include the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and IUCN’s Species Survival Commission.

For further information on any aspect of this programme please contact:

Paul Pearce-Kelly, Chair WAZA/CBSG Climate Change Task Force (ppk@zsl.org)

References and further reading

Junhold, J & F. Oberwemmer (2011). How are the animal keeping and conservation philosophy of zoos affected by climate change? Int. Zoo Yb. 45 (1): 99-107 http:// onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.

1748-1090.2010.00130.x/abstract

Khela, S & P. Pearce-Kelly (2011). An Iterative Reference List of Climate Change Science, Policy & Related Information. ZSL and WAZA/CBSG Climate Change Task Force. http://www.bioclimate.org/references/3382 Roiz, D., M. Neteler, C. Castellani, D. Arnoldi & A. Rizzoli(2011). Climatic Factors Driving Invasion of the Tiger Mosquito (Aedes albopictus) into New Areas of Trentino, Northern Italy.PLoS ONE 6 (4): e14800 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014800 http://www.plosone.org/ article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0014800 Fang, J. (2010). Ecology: A world without mosquitoes.

Nature 466: 432-434. doi:10.1038/466432a http:// www.nature.com/news/2010/100721/full/466432a.html McCarthy, M., M. Best, & R. Betts (2010). Climate change in cities due to global warming and urban effects.

Geophys. Res. Lett. Vol 37 L09705, doi:

10.1029/2010GL042845. http://www.agu.org/pubs/ crossref/2010/2010GL042845.shtml

Paaijmans, K.P., S. Blanford, A.S. Bell, J.I. Blanford, A.F. Read & M.B. Thomas (2010). Influence of climate on malaria transmission depends on daily temperature variation. PNAS 107 (34): 15135-15139. http:// www.pnas.org/content/107/34/15135.short

Barbosa, A. (2009). The role of zoos and aquariums in research into the effects of climate change on animal health. Int. Zoo Yb. 43 (1): 131 – 135. http:// onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.

1748-1090.2008.00073.x/abstract

Chaves, L.F., C.L. Keogh, G.M. Vazquez-Prokopec & U.D. Kitron (2009). Combined sewage overflow enhances oviposition of Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae) in urban areas. J. Medical Entomology 46 (2): 220-226. http://www.bioone.org/doi/abs/10.1603/033.046.0206 Bonilauri, P., R. Bellini, M. Calzolari, R. Angelini, L. Venturi, F. Fallacara, P. Cordioli, P. Angelini, C. Venturelli, G. Merialdi & M. Dottori (2008).

Chikungunya virus in Aedes albopictus, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis. 14 (5): 852-4. http://www.cdc.gov/eid/content/ 14/5/852.htm

Bradshaw, W.E., & C.M. Holzapfel (2008). Genetic response to rapid climate change: it's seasonal timing that matters. Molecular Ecology 17 (1):157 -166. http:// onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-294X. 2007.03509.x/abstract

Enserink, M. (2008). A Mosquito goes Global. Science 320 (5878): 864-866. http://www.sciencemag.org/content/ 320/5878/864.summary Global Invasive Species Database (Retrieved 2008-08-21) 100 of the World's Worst Invasive

Alien Species. http://www.issg.org/database/species/ search.asp?st=100ss

Kearney, M., W.P. Porter, C.K. Williams, S.A. Ritchie & A.A. Hoffmann (2008). Integrating biophysical models and evolutionary theory to predict climatic impacts on species’ ranges: the dengue mosquito Aedes aegypti in Australia. Functional Ecology 23 (3): 528-538. http:// onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.

1365-2435.2008.01538.x/abstract

Pluskota, B., V. Storch, T. Braunbeck, M. Beck & N. Becker (2008). First record of Stegomyia albopicta

(Skuse) (Diptera: Culicidae) in Germany. Eur. Mosq. Bull. 26: S. 1-5. PDF 257 kb

Angelini, R., et al. (2007). Chikungunya in north-eastern Italy: a summing up of the outbreak. Euro Surveill.12(47): 3313. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx? ArticleId=3313

Confalonieri, U., B. Menne, R. Akhtar, K.L. Ebi, M. Hauengue, R.S. Kovats, B. Revich & A. Woodward (2007). Human health. Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, M.L. Parry, O.F. Canziani, J.P. Palutikof, P.J. van der Linden and C.E. Hanson, Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 391-431. http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/ wg2/ar4-wg2-chapter8.pdf

Cuéllar-Jiménez, M.E. et al. (2007). Detectión de Aedes albopictus (Skuse) (Diptera: Culicidae) en la ciudad de Cali, Valle del Cauca, Colombia. Biomédica 27: 273-279.

ECDC/WHO (2007). Mission Report -Chikungunya in Italy. http://ecdpc.europa.eu/pdf/071030CHK_mission_ITA.pdf Scholte, J.E. & F. Schaffner (2007). Waiting for the tiger: establishment and spread of the Aedes albopictus mosquito in Europe. Emerging pests and vector-borne diseases in Europe. Volume 1, herausgegeben von W. Takken & B. G. J. Knols. Wageningen Academic Publishers. Tsetsarkin, K.A., D.L. Vanlandingham, C.E. McGee & S. Higgs (2007). A Single Mutation in Chikungunya Virus Affects Vector Specificity and Epidemic Potential. PLoS Pathog 3 (12): e201. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.0030201. http://www.plospathogens.org/article/info:doi/10.1371/ journal.ppat.0030201

Derraik, J.G.B. (2006). A Scenario for Invasion and Dispersal of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in New Zealand. J. Med. Entomol. 43(1): 1-8. http://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16506441 Romi, R., F. Severini & L. Toma (2006). Cold

acclimation and overwintering of female Aedes albopictus in Roma. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 22(1): S. 149-151. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16646341

Devi, N.P. & R.K. Jauhari (2005). Habitat biodiversity of mosquito richness in certain parts of Garhwal (Uttaranchal), India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 36 (3): 616-22. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16124427 Russell, R.C., C.R. Williams, R.W. Sutherst & S.A. Ritchie(2005). Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus -A Dengue Threat for Southern Australia? Commun. Dis. Intell. 29(3): S. 296-298. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ 16220868

Woodworth, B.L. et al (2005). Host population

persistence in the face of introduced vector-borne diseases: Hawaii amakihi and avian malaria. PNAS 102 (5):

Kutz, S.J., E.P. Hoberg, J. Nagy, L. Polley & B. Elki (2004). ‘Emerging’ Parasitic Infections in Arctic Ungulates.

Integr. Comp. Biol. 44 (2): 109-118. http:// icb.oxfordjournals.org/content/44/2/109.abstract Sutherst, R.W. (2004). Global Change and Human Vulnerability to Vector-Borne Diseases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 17 (1): 36-173. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC321469/

Carrieri, M., M. Bacchi, R. Bellini & S. Maini (2003). On the Competition Occurring Between 'Aedes albopictus' and 'Culex pipiens' (Diptera: Culicidae) in Italy. Environ. Entomol. 32(6):1313–1321. http://www.bioone.org/doi/ abs/10.1603/0046-225X-32.6.1313

Mylène, W. (2003). Mosquitoes' resistance to insecticides: different species share the same mutation. http://www.cnrs.fr/cw/en/pres/compress/mosquitoes.htm Song, M., B. Wang, J. Liu & N. Gratz (2003). Insect vectors and rodents arriving in China aboard international transport. J. Travel Med. 10 (4): 241-4. http://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12946302

Harvell, C.D. et al (2002). Climate Warming and Disease Risks for Terrestrial and Marine Biota. Science 296 (5576): 2158 – 2162. http://www.sciencemag.org/content/ 296/5576/2158.abstract

Hay, S.I., J. Cox, D.J. Rogers, S.E. Randolph, D.I. Stern, G.D. Shanks, M.F. Myers & R.W. Snow (2002). Climate change and the resurgence of malaria in the East African highlands. Nature 415: 905-909. http://

www.nature.com/nature/journal/v415/n6874/full/ 415905a.html

Fontenille, D. & J.C. Toto (2001). Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse), a potential new Dengue vector in Southern Cameroon. Emerging Infectious Diseases 7 (6): 1066–1067. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC2631913/

Kovats, R.S. et al (2001). Early effects of climate change: do they include changes in vector-borne disease?

Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London B. 29 (356): 1057-1068. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1088500/ Gratz, N.G. (1999). Emerging and resurging vector-borne diseases, Annu. Rev. Entomol. 44: 51-75. http://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9990716

Estrada-Franco, R.G. & G.B. Craig (1995). Biology, disease relationship and control of Aedes albopictus. Pan American Health Organization, Washington DC: Technical Paper No. 42. http://publications.paho.org/product.php? productid=313

Hanson, S.M. & G.B. Craig (1995). Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culcidae) Eggs: Field Survivorship During Northern Indiana Winters. J. Med. Ent. 32(5): 599-604. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7473614

O’Meara, F., L.F. Evans, A.D. Gettman & J.P. Cuda (1995). Spread of 'Aedes albopictus' and decline of 'Ae. aegypti' (Diptera: Culicidae) in Florida. J. Med. Entomol. 32 (4): 554-562. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ 7650719

Thaddeus, K. et al (1995). Avian Malaria Seroprevalence in Jackass Penguins (Spheniscus demersus) in South Africa.

The Journal of Parasitology, 81 (5): 703-707. http:// www.jstor.org/pss/3283958

Graczyk, T.K. et al (1994). Characteristics of Naturally Acquired Avian Malaria Infections in Naive Juvenile African Black-footed Penguins (Spheniscus demersus). Parasit. Res.

80 (8): 634-637. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/ 7886030

Graczyk T.K. et al (1994). Maternal Anti-Plasmodium spp. Antibodies in African Black-footed Penguins

(Spheniscus demersus) Chicks. J. Wildl. Dis. 30 (3): 365-371. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7933279

Hornby, J.A. & T.W. Miller (1994). 'Aedes albopictus' distribution, abundance, and colonization in Lee County, Florida, and its effect on 'Aedes aegypti'. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 10 (3): 397-402. http://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7807083

Nishida, G.M. & J.M. Tenorio (1993). What Bit Me? Identifying Hawai'i's Stinging and Biting Insects and Their Kin. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu.

Clements, A. (1992). The biology of mosquitoes. 1: Development, Nutrition and Reproduction. London: Chapman & Hall.

Savage, H.J.M. et al (1992). First record of breeding populations of Aedes albopictus in continental Africa: Implications for arboviral transmission. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc 8(1): 101-103. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

pubmed/1583480

CDC [Centers for Disease Control] (1989). Update:

Aedes albopictus infestation United States, Mexico. Morb Mort Week Rpt 38: 445–446. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/ preview/mmwrhtml/00001413.htm

Hawley, W.H. et al (1989). Overwintering Survival of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) Eggs in Indiana. J. Med. Entomol. 26(2): 122-129 http://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2709388

Hawley, W.A. (1988). The biology of Aedes albopictus. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. (Supplement) 1: 2-39. http:// www.citeulike.org/user/neteler/article/2836765 Forattini, O.P. (1986). Identification of Aedes

(Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse) in Brazil. Revista de Saude Publica (Sao Paulo) 20 (3): 244-245. http://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3809982

Means, R.G. (1979). Mosquitoes of New York Part I. The genus Aedes Meigen with identification to genera of Culicidae. Bulletin 430a. 221. p. Albany, NY: The State Education Department.

Bohart, R.M. & R.K. Washino (1978). Mosquitoes of California. Div. Agric. Sci. Univ. Calif. Berkeley, CA. Griffitts, T.H.D. & Griffitts, J.J. Mosquitoes Transported by Airplanes: Staining Method Used in Determining Their Importation , Public Health Reports (1896-1970), 46 (47): 2775-2782

ZOO/WILD and its networks CCINSA and RISCINSA organized five-days hands on training workshop hosted by Department of Wildlife, College of Forestry, Kerala Agricultural University. Thirty five bat and rodent researchers from India (Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, Himachal Pradesh), Sri Lanka and Nepal attended this programme. Prof. Paul Racey, Visiting Professor,

Department of Exeter in Cornwall, Co chair, Bat Specialist Group of IUCN’s SSC, Dr. Mike Jordan, Senior Conservation Advisor, National Zoological Gardens of South Africa, Regional Chair IUCN SSC

Reintroduction Specialist Group were the lead trainers. Dr. Sanjay Molur, ZOO, Dr. P.O. Nameer and Dr. N. Singaravelan handled sessions. This training was sponsored by Chester Zoo, Knowsley Safari Park, Columbus Zoo and Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, USA.

During the inaugural, Dr. Nameer, College of Forestry, Kerala Agricultural University, host of the workshop, welcomed the gathering. He said ‘this is an extremely important exercise, hands on training workshop in small mammals, that we will be having for the next five days. Small mammals are an important group of mammals because they constitute about

60-70% of mammalian diversity of the world. In spite of this, very little is known about them. ZOO is organizing training workshops on this since 2000 and organized training programmes in all south Asian countries and KAU is hosting for the second time. ZOO trained many researchers and they are generating small mammal information from all South Asian countries’.

Dr. Mohan Kumar, Dean, College of Forestry said ‘I hope this training will produce a critical mass of a research workers and Scientist in the area of small mammal conservation to work in South Asia and they carry forward the research for this neglected group of organism”.

Prof. Pushpa Latha, Registrar, KAU while inaugurating the workshop said that the importance of this training is very clear since every creature has a role in its ecosystem. Though small mammals constitute 60-70% of all mammals they are highly neglected. From the time memorial we are worshiping some rodents eg Shrew,

have many myths related to bats and rodents. This workshop will help to save the beautiful creature of nature.

Sally Walker, Founder CCINSA / RISCINSA and ZOO during her talk shared the history of these workshop series. She said, this kind of workshop started with the IUCN Red List exercise in India. ZOO was interested in Conservation Assessment and

Management Plan workshop which is a creation of Dr. Ullie Seal who was the Chairman of IUCN SSC CBSG. In 1996 Government of India conducted Biodiversity Conservation Prioritization Project BCPP and as a part of it ZOO offered to help assess all the species of India. We divided species assessment

in to seven workshops and one of the workshops was mammals. I learned that rodents and bats are the most species and actually there were very few experts we could call. Later after CAMP workshops ZOO started networks for lesser known groups and I started a network for Bats and rodents. We combined bat and rodents since bats can be studied during night time and rodents during day. We had this workshop combining Chiroptera and different rodents. Paul and Mike were

Small Mammal Field Techniques Training, Thrissur, Kerala

B.A. Daniel1 and P.O. Nameer2

1Scientist, ZOO, Coimbatore. badaniel@zooreach.org 2Asst. Prof. Kerala Agricultural University, Kerala.

Dignatories on the dias during inaugural

our resource persons for all our workshops. I feel that animals should not be mistreated. Our trainers teach us to treat the animals well. She thanked KAU for hosing this training for the second time.

Paul Racy expressed his happiness to be here after eight years. The last workshop was very successful that generated interest from mammal researchers from all over India. He also said that IUCN has many commissions and SSC is one of the commissions. Bat Specialist group is one of the SG of SSC. Priority of BSG is action planning for conservation priority. Action plans have 20 major recommendations. The current priority of BSG is to revise the action plans. It will be a web based plan and will be updated systematically.

Mike Jordon said it is a pleasure to be back to Kerala. This training has created scientists producing

information about small mammals in India and South Asia. There is so much to be achieved to save this group of species.

Sanjay thanked Kerala Agricultural University, staff and students for their assistance in organizing the training. He also thanked Knowsley Safari Park, Chester ZOO and Columbus zoo for their funding support and to CBSG as our mentor.

The programme started with self-introduction by all participants. Please see annexure 1 for names of

participants and their expectations.

As an introduction to small mammals, Mike Jordan spoke about biodiversity of non-volant small mammals of the orders rodentia, insectivora and scandentia. He stressed upon the disparity and the neglect that is being received by the

small mammals, though they account for about 55% of the mammals of the world. Paul Racey, as an introduction to Volant small mammals gave a detailed introduction of bats with classification, general features, taxonomy, distribution ecology, feeding ecology etc. He added that first fossil bat was found 50MYa that belonged to Eocene period that had very long wings developed long ago. They already had echolocation. As on 2010 about 1124 bat species has been reported which accounts about 20% of mammals. There are still more to be described. Chiroptera is classified into Megachiroptera – 1 Family Pteropidae (old world fruit bats) and

Microchiroptera – 17 families. Some recent editors do not use mega and micro instead they use

Yinpterochiroptera and

Yangochiroptera based on molecular genetics data.

Field techniques: For non-volant different types of traps used for the study of rodents was explained. During the training live and single capture traps of varying dimensions were used. All aspects of Sherman trap was explained including cost and trap maintenance. Other traps generally used for rodent work such as Wire mesh traps, multi-capture traps such as Uglan Traps were also discussed. With regard to Volant mammals different types of nets to survey bats such as mist nets. Harp nets, canopy nets, bat detectors, flick nets were explained. Foraging strategy of bats was explained.

Demonstration on trap setting and mist nets: Entire evenings of all workshop days were utilized to set up traps or mist nets. The Sherman traps set was monitored periodically and trapped rodents were used to learn handling, species identification, sexing, marking weighing, age determination and breeding conditions of the species. After marking the species were released back in the same location caught. During trap setting, details about preparation of the baits for setting the traps were discussed. The participants were divided into groups and were taken to the nearby

plantation areas for the demonstration of setting of traps. A total of about 40 traps were set at different plantation areas. Similarly mist net setup was demonstrated in orchards with in KAU campus and the participants in groups learned to set up mist nets during evenings. Identification of habitats and sampling methodologies were discussed during demo practice. Among non-volant mammals, Rattus rattus, Mus booduga, Bandicoota bengalensis, and among Volant

A session on rodent handling and sexing by Dr. Mike Jordan

mammals, Cynopterus sphinx, Hipposideros ater, Hipposideros speoris, Rhinolophus rouxii were caught.

As part of practice for identifying the species caught, dichotomous key and character matrix for identification of bats in the field was taught. During the course of bat examination, sexing, the breeding condition of the bats such as lactating females, pregnancy and age estimation.

Marking techniques: During classroom and field sessions different methods of marking the bats such as temporary marking (marker pen, varnish), permanent marking (forearm bands/rings, necklace, tattooing, bleaching the fur) were explained and demonstrated. Study of the foraging behaviour of the bats, radio-tracking studies, use of bat detectors etc were explained by Paul. Mike explained methods of marking of rodents such as Microchipping, ear tagging and fur clipping.

Dry skin preservation of small mammals: Maintaining voucher specimens are of great importance in taxonomy studies. Dry skin preservation help to retain the original colour and shape of the animal for a longer period and also the technique is very simple that require limited equipments like a pair of scissors and borax powder. P.O. Nameer demonstrated the dry skin preservation techniques of rodents (carding) for storage in the museum.

Animal handling: Welfare of animals is a very important component in research who may do not care for welfare. The trainers explained about the welfare needs of the animal. Underlying principles in animal handling and restrain is that the same should be safe to the human as well as to the animal.

Pollination by rodents and bats: Interaction between animals and plants are mutualistic. Among mammals fruit bats and some mammals are pollinators. Frugivorous and nectarivorous bats pollinate and disperse seeds of hundreds of species of plants. Dr. N. Singaravelan gave a talk on pollination ecology of bats giving examples and case studies reported from different parts of the world. He also gave a demonstration on pollination aspects.

Dr. Sanjay Molur, gave a presentation on methods on population estimation of small mammals based on his thesis work. He also explained about the small mammal networks Chiroptera Conservation and Information Network of South Asia (CCINSA) and Rodentia, Insectivora, Scandentia Conservation and Information Network of South Asia (RISCINSA).

At the end of the workshop the participants committed to contribute for the conservation of small mammals. At the end all participants received a certificate of participation.

A wildlife researcher handling a bat