S H O R T C O M M U N I C A T I O N

Habitat use analysis of Dian’s tarsier (

Tarsius dianae

)

in a mixed-species plantation in Sulawesi, Indonesia

Stefan MerkerÆIndra Yustian

Received: 16 August 2007 / Accepted: 18 September 2007

ÓJapan Monkey Centre and Springer 2007

Abstract To investigate the importance of mixed-species plantations as a potential habitat for small arboreal primates, we radio-tracked six Dian’s tarsiers (Tarsius dianae) in such an area in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, and explored their selectivity for certain vegetation types. The animals strongly favored sporadic dense shrubbery over more open structures, yet they also utilized cash-crop cultivations for hunting insects. This paper documents the first habitat use analysis of tarsiers on agricultural land and exemplifies the vital role of mixed-species plantations in conserving wildlife when nearby forest is logged.

Keywords Cocoa Home rangePrimates Radio trackingTarsius dentatus

Introduction

Deforestation and habitat modification cause the decline of primate populations around the tropical world (Johns and Skorupa1987). In Indonesia, this is not only true for the large and space-demanding species such as orang-utans, gibbons or macaques, but also for the lesser-known, small-bodied, and nocturnal tarsiers. These animals were formerly classified along with lemurs and lorises as pros-imians (Simpson1945), yet anatomical, reproductive, and

genetic characters mostly suggest that they would better be grouped with monkeys and apes into the suborder Haplo-rhini (Martin 1990; Schmitz et al.2001). With head-and-body lengths of about 12 cm, tarsiers weigh little more than 100 g. These strictly faunivorous primates are ende-mic to the Greater Sunda Islands (all but Java) and the Philippines.

Six tarsier species have been described thus far on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. Dian’s tarsier (Tarsius dianae1) occurs in the lowlands and lower montane forests of Central Sulawesi. This species lives in small groups of up to seven individuals (Merker2003). Population densities of Dian’s tarsier have declined over the past years due to intensified logging (Merker2003; Merker et al.2004). This finding corroborates previous observations of imminent threats to other tarsier species (MacKinnon and MacKinnon

1980; Leksono et al. 1997; Gursky1998). Since the con-version of natural lowland forest into cash-crop plantations appears to be an almost unstoppable process, assessing the adaptability of tarsiers to such areas is essential for pre-dicting these animals’ chances of survival.

Thoughts on the interface between tarsier biology and agriculture are not new. Leksono et al. (1997) found tarsiers in several cultivated areas of Sulawesi, reported on common human misperceptions of these animals, e.g., that tarsiers feed on cash-crops, and even suggested that tarsier popu-lations could be managed as a natural pesticide. They did not find these primates in areas of intensive coconut farming but did observe them foraging in a mix of coconut and cocoa cultivation. There, the animals frequently had sores on their hands and anogenital regions. Some agricultural practices inside the natural forest, however, might have

S. Merker (&)

Institute of Anthropology, Johannes-Gutenberg University Mainz, Colonel-Kleinmann-Weg 2 (SB II),

55099 Mainz, Germany e-mail: tarsius@gmx.net

I. Yustian

Department of Biology, Sriwijaya University, Palembang, Indonesia

1 Shekelle et al. (1997) pointed out this might be a junior synonym to T. dentatus.

123

Primates

desirable effects on tarsiers. Small forest coffee gardens, for instance, positively affect Dian’s tarsier population densi-ties and ranging patterns (Merker et al.2004,2005; Merker

2006).

A common and increasingly important practice in Indonesia—mostly due to scattered land ownership and crop rotation—is to cultivate several crop species side by side. In Madagascar, lemur densities in such mixed-species plantations are high (Ganzhorn1987). The study reported here aimed at revealing the habitat use of Dian’s tarsiers in such an area in Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. Of particular importance was the identification of typical vegetation structures crucial for the presence of tarsiers in this disturbed habitat.

Methods

From August to October 2001, five tarsier groups were located in a 25-ha mixed-species plantation close to the northeastern boundary of Lore-Lindu National Park, Sulawesi, Indonesia (01°11050@S, 120°09026@E, 650–730 m

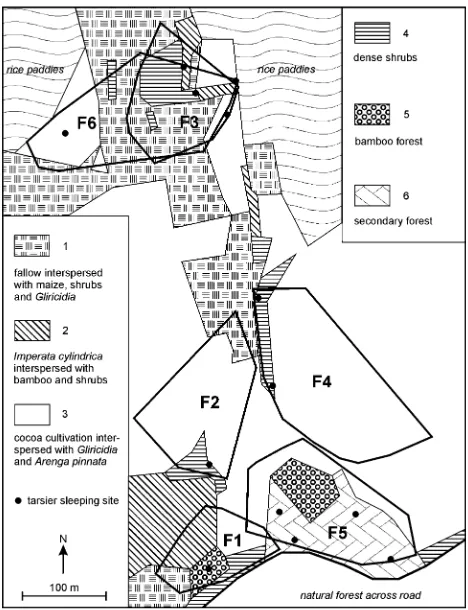

asl). This plantation comprised cocoa, maize, bamboo, and the leguminous treeGliricidia sepium(Jacq.) Steud. mostly being used as living fence posts, fodder or fuelwood, and for crop shade and improved fallow. The rhizomatous perennial grass Imperata cylindrica L. (alang–alang), a colonizer of degraded humid tropical forest soils, domi-nated the fallow land between cultivated crops. A patch of young secondary forest with a canopy height of ca. 10 m constituted the edge of the plantation towards old-growth natural forest. Six different vegetation types were mapped (Fig.1) using measuring tape and a compass.

Nine tarsiers were captured using mist nets opened at dusk and dawn in the vicinity of their sleeping sites. Six adult females (from five groups, Fig.1) were fitted with 3.3-g radio collars (Holohil Systems, Carp, ON, Canada) and were subsequently radio-tracked over the course of 2 weeks. The choice of females as focal animals was due to the design of a more comprehensive research project comparing tarsier ranging patterns between different hab-itats (Merker et al.2004,2005; Merker2006).

Data collection comprised shifts in the evening (1800– 2200), in the morning (0400–0630), and full-night fol-lows. Home ranges were estimated by drawing minimum convex polygons (MCPs) around the outermost data points (Fig.1). Since bearings within full-night shifts were taken every 15 min (every 40 min during the other shifts), they were likely to be intercorrelated (Merker

2003) and therefore omitted from the analysis described here. Thus, a total of 32 track points (n=31 for F5) were available for each animal to be used in a habitat use analysis.

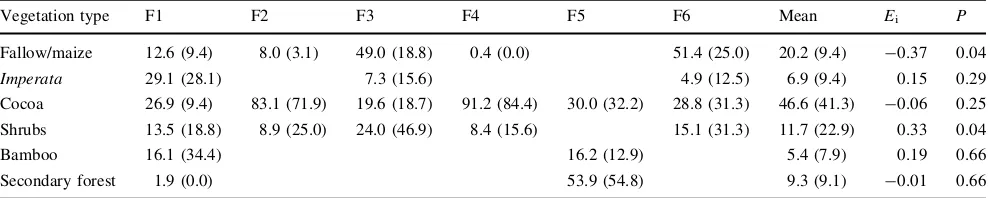

The MCPs were superimposed on the map of vegetation types (Fig.1). The percentage of a particular vegetation type within a tarsier home range was considered as avail-able area. To determine the utilized fragments, data points were plotted on the habitat map. The proportional use of vegetation types was calculated by dividing the number of locations in each fragment by the total number of track points for this animal. The proportions of available vs. utilized types were compared using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (Wilcoxon 1945). To test for selection or avoid-ance of particular structures, Ivlev’s electivity indexEiwas calculated for each vegetation type as Ei =(ui-ai)/ (ui+ai) whereuiis the mean proportion of observations in vegetation typei(habitat utilized) andaiis the mean pro-portion of vegetation type i available in the tarsier home ranges (Lechowicz1982).

Results

Tarsiers avoided fallow land and maize fields and strongly selected dense shrubbery for sleeping and traveling (Table 1). Young secondary forest, Imperata cylindrica grassland, bamboo groves, and cocoa plantations were

Fig. 1 Study plot with six different vegetation types, home ranges of

six female Dian’s tarsiers (F1–F6) and commonly used tarsier sleeping sites

Primates

neither avoided nor strongly selected. Consistently, tarsiers utilized multiple kinds of vegetation including cocoa cul-tivations and Imperata cylindrica expanses. Only one condition applied to all these observations—dense shrubs, forest remnants or at least bamboo stands had to be nearby to provide a suitable sleeping site. According to the land owners, no insecticides were used but herbicides were applied in this plot (2, 4-dimethylamine, glyfosate-isopro-pylamine). However, no unusual incidence of sores on the hands or the anogenital region of these tarsiers was detected. Although the tracking period was limited to 2 weeks, the tarsiers were observed over the course of ca. 10 weeks. During this time, the sleeping sites as shown in Fig.1 were consistently used, and tarsier ranges did not change to a degree obvious to the human observer.

Discussion

Remnant forest patches or dense shrubbery can render agricultural land as suitable tarsier habitat. As documented in a previous study on tarsiers in this mixed-species plan-tation (Merker et al.2005), tarsier group sizes are slightly smaller, and the population density is significantly smaller than in undisturbed forest. Furthermore, Merker et al. (2005) found female home ranges to be significantly larger than in pristine or less-disturbed plots. The authors mainly attribute this to a reduced insect abundance in the planta-tions. Body weights, head-and-body lengths, ectoparasite loads, and group composition were not found to be dif-ferent between these study sites (Merker et al. 2005). Although these population parameters indicate more diffi-cult survival under such intensive anthropogenic influence than in natural forest, such areas could be effective ele-ments of metapopulations and stepping stones or corridors for gene exchange. When forest is clear-cut, nearby plan-tations might serve as temporary refuge for a future re-colonization of the succession areas.

As the investigated plot lies in close vicinity to natural forest (a potential source habitat), it cannot be assessed here whether tarsier populations farther away from larger forest patches are able to maintain sufficiently large populations and gene exchange to avoid inbreeding. In this particular plot, microsatellite analyses revealed no reduced allelic variability and no increased relatedness among these nine tarsiers indicating effective dispersal (S.M., unpublished data). Follow-up studies including further genetic analyses as well as a thorough investiga-tion of reproductive success in disturbed areas are needed. Based on the results of this short study, keeping or cre-ating a mosaic of natural structures (e.g., shrubs, bamboo) among the cash-crop cultivations as well as a shrub fringe at the plantation border is recommended. Hedges or tracts of Imperata cylindrica could effectively link tarsier-friendly plantations.

Acknowledgments We wish to thank LIPI, PHKA, POLRI, and

BTNLL for granting research permits; Jatna Supriatna and Noviar Andayani from UI Jakarta for officially sponsoring the studies; and Leo, Sapri, and Thony for their help in the field. No animal was harmed, and all radio-collars were retrieved after tracking. The study was part of a larger research project supported by the German Academic Exchange Service and the German National Academic Foundation.

References

Ganzhorn JU (1987) A possible role of plantations for primate conservation in Madagascar. Am J Primatol 12:205–215 Gursky S (1998) The conservation status of two Sulawesian tarsier

species: Tarsius spectrum and Tarsius dianae. Prim Conserv 18:88–91

Johns AD, Skorupa JP (1987) Responses of rain-forest primates to habitat disturbance: a review. Int J Primatol 8:157–191 Lechowicz MJ (1982) The sampling characteristics of electivity

indices. Oecologia 52:22–30

Leksono SM, Masala Y, Shekelle M (1997) Tarsiers and agriculture: thoughts on an integrated management plan. Sulawesi Primate Newsl 4:11–13

Table 1 Abundance of vegetation types (as a percentage of tarsier home range) and their utilization by six female Dian’s tarsiers (in

paren-theses, in percent) in a mixed-species plantation in Sulawesi

Vegetation type F1 F2 F3 F4 F5 F6 Mean Ei P

Fallow/maize 12.6 (9.4) 8.0 (3.1) 49.0 (18.8) 0.4 (0.0) 51.4 (25.0) 20.2 (9.4) -0.37 0.04

Imperata 29.1 (28.1) 7.3 (15.6) 4.9 (12.5) 6.9 (9.4) 0.15 0.29 Cocoa 26.9 (9.4) 83.1 (71.9) 19.6 (18.7) 91.2 (84.4) 30.0 (32.2) 28.8 (31.3) 46.6 (41.3) -0.06 0.25

Shrubs 13.5 (18.8) 8.9 (25.0) 24.0 (46.9) 8.4 (15.6) 15.1 (31.3) 11.7 (22.9) 0.33 0.04 Bamboo 16.1 (34.4) 16.2 (12.9) 5.4 (7.9) 0.19 0.66 Secondary forest 1.9 (0.0) 53.9 (54.8) 9.3 (9.1) -0.01 0.66

EiIvlev’s electivity index,Pfor Wilcoxon signed-rank test,Ffemale

Blanksdenote the absence of a vegetation type in a particular home range. Mean calculated over all six home ranges, regardless of occurrence of the vegetation type

Primates

MacKinnon J, MacKinnon K (1980) The behavior of wild spectral tarsiers. Int J Primatol 1:361–379

Martin RD (1990) Primate origins and evolution—a phylogenetic reconstruction. Chapman & Hall, London

Merker S (2003) Vom Aussterben bedroht oder anpassungsfa¨hig? Der Koboldmaki Tarsius dianae in den Regenwa¨ldern Sulawesis. PhD Thesis, Georg-August University, Go¨ttingen.http://webdoc. sub.gwdg.de/diss/2003/merker

Merker S (2006) Habitat-specific ranging patterns of Dian’s tarsiers (Tarsius dianae) as revealed by radiotracking. Am J Primat 68:111–125

Merker S, Yustian I, Mu¨hlenberg M (2004) Losing ground but still doing well—Tarsius dianae in human-altered rainforests of Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. In: Gerold G, Fremerey M, Guhardja E (eds) Land use, nature conservation and the stability

of rainforest margins in Southeast Asia. Springer, Heidelberg, pp 299–311

Merker S, Yustian I, Mu¨hlenberg M (2005) Responding to forest degradation: altered habitat use by Dian’s tarsierTarsius dianae

in Sulawesi, Indonesia. Oryx 39:189–195

Schmitz J, Ohme M, Zischler H (2001) SINE insertions in cladistic analyses and the phylogenetic affiliations ofTarsius bancanusto other primates. Genetics 157:777–784

Shekelle M, Leksono SM, Ichwan LLS, Masala Y (1997) The natural history of the tarsiers of North and Central Sulawesi. Sulawesi Primate Newsl 4:4–11

Simpson GG (1945) The principles of classification and a classifica-tion of mammals. Bull Am Mus Nat Hist 85:1–350

Wilcoxon F (1945) Individual comparisons by ranking methods. Biometrics 1:80–83

Primates