Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:39

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

An Empirical Test of Mnemonic Devices to Improve

Learning in Elementary Accounting

Gregory Kenneth Laing

To cite this article: Gregory Kenneth Laing (2010) An Empirical Test of Mnemonic Devices to Improve Learning in Elementary Accounting, Journal of Education for Business, 85:6, 349-358 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832321003604946

Published online: 13 Feb 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 228

View related articles

JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS, 85: 349–358, 2010 CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832321003604946

An Empirical Test of Mnemonic Devices to Improve

Learning in Elementary Accounting

Gregory Kenneth Laing

University of the Sunshine Coast, Maroochydore DC, Queensland, Australia

The author empirically examined the use of mnemonic devices to enhance learning in first-year accounting at university. The experiment was conducted on three groups using learning strategy application as between participant’s factors. The means of the scores from pre- and posttests were analyzed using the studentttest. No significant difference was found between the groups for the pretest; however, both treatment groups performed significantly better in the posttest than did the control group. The findings support the literature that mnemonic devices can accelerate the rate at which new information is acquired and improve formal reasoning. A model is introduced for assessing the characteristics which affect memory recall.

Keywords: accounting education, memory cue, mnemonic devices

Mnemonic devices are strategies used to enhance memory. The termmnemonicis derived from the name of the ancient Greek goddess of memory, Mnemosyne.Mnemonicliterally means to aid the memory (Bourne, Dominowski, Loftus, & Healy, 1986). Mnemonic devices have proven effective in helping students to remember new information (Joyce & Wiel, 1986). Mnemonic devices linking new information to something already familiar to a student were found to be the most effective. That is, they were very helpful for recalling conventions that were not logically connected to content stu-dents had already conceptualized. Subsequently, mnemonic devices, such as acrostics, acronyms, narratives, and rhymes, can assist in making abstract material and concepts more meaningful for individuals. To clarify the terminology, an acrostic is a phrase or poem in which the first letter of each word or line functions as a cue (e.g., Every Good Boy De-serves Fruit [used to identify musical notes]). An acronym is a word formed out of the letters of a series of words (e.g., FACE is used in teaching music). A narrative is a story that incorporates the words in the appropriate order (e.g., Every Good Boy Deserves Fruit, which is also used in teaching music). A rhyme accentuates the sound between words (e.g.,

ibeforeeexcept aftercis used to teach spelling).

Kiewra (1989), Palinscar and Brown (1989), and King (1992, 1994) identified learner- and teacher-based

strate-Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Gregory Kenneth Laing, University of the Sunshine Coast, Faculty of Business, Maroochydore DC, QLD 4558, Australia. E-mail: glaing@usc.edu.au

gies that facilitated learner’s memory of material presented in lectures or in texts. Woloshyn, Willoughby, Wood, and Pressley (1990), Pressley et al. (1992), and Wood, Need-ham, Williams, Roberts, and Willoughby (1994) examined an associative learning strategy, elaborative interrogation, which enhanced memory through the use of responses to

whyquestions. They found that student performance could be improved by elaborations that provided more meaning to material being taught.

Research has found that learning can be improved in knowledge domains that are abstract and highly structured by the use of more directive teaching strategies (Carroll, 1994; Debrowski, Wood, & Bandura, 2001; Sweller, 1999; Tuovinen & Sweller 1999). The educational literature is re-plete with research that identifies the benefits of the use of mnemonic teaching strategies. In particular, mnemonic de-vices have been found to accelerate the rate at which new information is acquired (Levin & Pressley, 1985; Wang & Thomas, 1996), improve problem-solving tasks involving both analytical thinking as well as formal reasoning (Levin & Levin, 1990), and be beneficial in terms of long-term memory (Marschark & Hunt, 1989).

Using mnemonics as a teaching strategy does not signify acquiescence to rote learning. Ausbel (1963) stressed the im-portance of cognitive structures on learning. He placed heavy emphasis on meaningful verbal learning, that is, the acquir-ing of information with various links to other ideas. This stands in direct contrast to rote learning, which emphasizes memorization of specific information without examining re-lationships within the material. Anderson and Armbruster

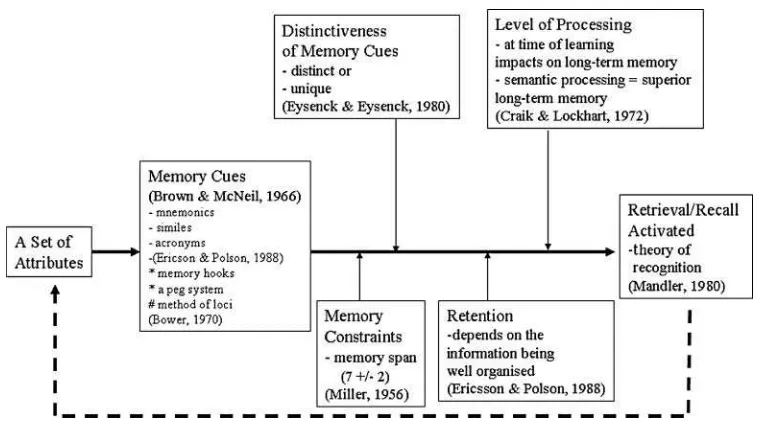

FIGURE 1 Model for assessing characteristics of a memory cue.

(1984) concluded that asking students to create mental im-ages of new material, make inferences, and draw networks of relationships all increased learning. For this reason, it is important that in the use of any mnemonic device the lec-turer has a clear and concise plan for addressing the relevance and relationship to the specific context. A mnemonic may be useful to develop deep learning even in students who would normally favor surface learning.

Although mnemonic devices have been shown to be ef-fective, there is a lack of research to explain why mnemonics work (Eysenck & Keane, 1995). To address this gap in the literature a model (Figure 1) has been constructed draw-ing on various aspects of the literature regarddraw-ing memory in an attempt to provide a method to examine the design and the potential usefulness of any memory cue (such as the mnemonic device). Note that for the purpose of the model the termmemory cue(Brown & McNeil, 1966) is used be-cause the mnemonic device is a form of memory cue and the basic principles addressed in the model should apply equally to assessing other types of memory cues. To commence it is necessary to determine a set of attributes pertaining to the material being covered. A memory cue may take the form of a mnemonic, simile, acronym or acrostic. Basically, whichever form the memory cue takes, the intention is for it to act as a stimulus to help gain access to memories (Brown & McNeil). Although other terms have been used to describe memory cues, such as memory hooks, a peg system, and method of loci (Bower, 1970), these serve the same purpose, which is to stimulate and provide recall of memory.

Having selected an appropriate type of memory cue, the next stage is to consider whether the cue is succinct making it easier to commit to memory. The memory cue should be kept to a reasonable size to accommodate an individual’s capacity for memorization. In the seminal paper by Miller (1956) an

individual’s short-term memory capacity was identified as being limited to seven items of information, plus or minus two (note that the information referred to may be numbers, letters or syllables). For the purpose of designing a memory cue it is therefore important to consider the number of items to be used as this could render the memory cue ineffective.

Having satisfied the need to keep the memory cue brief, the next stage is to determine whether the cue has distinct or unique characteristics that make it easier to recall. The distinctiveness theory (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1980) holds that memory cues that are distinctive or unique in some way are more readily retrievable than those that are not, and in this way long-term memory is affected by the distinctiveness of the memory cue. This leads to the next point for consid-eration, which is that retention depends on the information being well organized or structured. Ericksson and Polson (1988) found that retention was greatly increased when the information in the memory cues was well organized. Bower (1970) also found that hierarchical organization was partic-ularly helpful for retention of memory cues.

The next stage in the model deals with producing more durable memories. According to Craik and Lockhart (1972), memories that are better remembered and more easily re-called depend on the type of encoding or, more simply, the level of processing involved. They proposed that deeper lev-els of processing result in longer lasting memory. The types of encoding proposed by Craik and Lockhart are the following: structural, which emphasizes the physical structure of the cue or stimulus (shallow processing); phonemic structure, which emphasizes the sound (intermediate processing); and semantic structure, which emphasizes meaning and involves thinking about the objective and action the cue represents (deep processing). Therefore, it is important to consider the three types of encoding when evaluating the memory cue.

EMPIRICAL TEST OF MNEMONIC DEVICES 351 Having satisfied the requirements of the model to this

point, the next stage focuses on the activation of recall or retrieval of the information suggested by the memory cue. According to Mandler (1980), recognition and subsequent retrieval of the information is dependent on the familiarity with the memory cue. Thus if the level of familiarity is high the retrieval process occurs more rapidly. The desired out-come is for the memory cue to activate a recall of the set of attributes established at the beginning. The intention is for the students to gain experience in the use of the memory cue and thereby enhance their learning.

In the educational literature, learning and experience ap-pear to be interrelated constructs. As Kolb (1984) explained, “Learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience” (p. 38). Accord-ing to Kolb and Webb (2006), active involvement encour-ages accelerated learning and can accommodate difference in learning styles. In the cognitive literature, a distinction has been drawn between declarative (figurative) knowledge and operative (procedural) knowledge. Fundamentally, “declar-ative knowledge comprises the skills we know; procedu-ral knowledge comprises the skills we know how to per-form” (Anderson, 1980, p. 222). The cognitive processes involved in professional judgment are the result of the use of problem-solving and critical-thinking skills (Facione & Fa-cione, 2008). According to Facione and FaFa-cione, the goal of the judgment process is to decide what to believe or what to do in a given context, in relation to the available evidence, using appropriate conceptualizations and methods, and evaluated by the appropriate criteria. Cognitive processes such as anal-ysis and critical thinking share common attributes with Pi-aget’s (1972) concept of formal operational thought. PiPi-aget’s theory of cognitive development has a focus on operative knowledge and the development of reasoning skills. Accord-ing to Piaget’s theory, reasonAccord-ing at the level of formal opera-tional thought (formal reasoning) involves demonstrating ab-stract thinking and hypothetical–deductive reasoning, which are arguably important learning objectives at university.

There are discernible differences in the teaching at uni-versity between disciplines, and this may be due to actual differences in the fields of learning, such as the distinction between social sciences and natural sciences (Smeby, 1996). Accounting, for example, is a field of learning in which the concepts are relatively abstract and yet interconnected, which can make it difficult for some students to comprehend. In this respect it shares some similarities with the study of statistics (Gal & Garfield, 1997). For example, the concept of the ac-counting equation with its subsequent development of the notion of debits and credits, which are all essential knowl-edge of the accounting procedure to correctly identify and record a business transaction. Students therefore have to first know the elements of the equation and the nature of debits and credits before they can comprehend the accounting pro-cedures. This illustrates the hierarchical nature of accounting knowledge. That is, accounting knowledge is highly

struc-tured because of the interconnectivity of the concepts and the hierarchical nature of those concepts.

In the accounting discipline there is an emphasis on proce-dural knowledge, particularly in the elementary stage, which is concerned with the application of a set of rules for deter-mining which economic events constitute accounting trans-actions. The accounting process, as is usually explained in first-year accounting textbooks (for example Hoggett, Ed-wards, Medlin, & Tilling, 2009), involves identification, clas-sification, and recording of economic events. This cognitive process requires an analysis of the transactions in which a judgment has to be reached by answering questions such as the following:

• What type of ledger accounts are involved? (e.g., rent, land, wages)

• What category is each of the accounts? (e.g., asset, liabil-ity, revenue)

• What is the nature of the account? (e.g., debit, credit) • Is this an increase or decrease to the account?

• Which account is to be debited and which is to be credited?

This process involves analysis, interpretation, inference, and the ability to explain or justify the decision. The extent to which an accounting student has to be able to apply the basic principles in order to make a judgment about an economic transaction requires formal reasoning skills and it is in this regard that the mnemonic device has the potential to assist the learning process.

The use of mnemonic devices for teaching is widely acknowledged in the fields of medicine (Wilding, Rashid, Gilmore, & Valentine, 1986), psychology (Gumar & Martin, 1990), and education (Lockavitch, 1986; Miller, Peterson, & Mercer, 1993). In the discipline of accounting, opportu-nities have yet to be fully explored in the literature on how mnemonic devices may be used to improve learning. In this article, two mnemonic devices are examined to determine their usefulness in promoting learning within a first year in-troductory accounting course. The two mnemonic devices are PALER and ALORE and their application to teaching in-troductory accounting concepts is explained and illustrated in Appendixes A and B, respectively. Appendixes A and B provide a clear and concise plan for addressing the relevance and relationship to the specific context as suggested by An-derson and Armbruster (1984).

The first mnemonic device, PALER, has many good points to recommend it as a teaching tool. This mnemonic is con-sistent with the model presented in Figure 1, which follows the following principles:

1. The set of attributes are identified (for further detail, refer to Appendix A).

2. The memory cue selected in this instance is a mnemonic device.

3. The number of letters in the mnemonic is five, which is within the prescribed parameters.

4. The mnemonic is distinct or unique in nature in so far as it relates to accounting.

5. It is organized in accordance with the accounting equa-tion.

6. The level of processing in this circumstance is related to the manner and process involved in teaching or ex-plaining the relevance of the cues.

7. Recognition and retrieval are dependant on familiarity, which comes from reinforcing the use of the memory cue (mnemonic).

However, experience has revealed that some students found the use of this mnemonic to be complex and when under the stress of exams there existed a high potential to become confused.

An alternative mnemonic used for the same purpose of in-troducing students to the concepts of accounting is ALORE. This mnemonic also adheres to the principles established previously in accordance with the model (Figure 1). The use of this mnemonic device has proven to be less problematic for students, especially pertaining to recall and application in exam situations. This acronym repositions the letters and refers to Assets, Liabilities, Owner’s Equity, Revenue, and Expenses. The simplicity of this mnemonic for students is that they have less to remember and the principles underpin-ning the device are more intuitively logical.

Positive comments from students from the previous use of PALER included the following:

I didn’t get the debit and credits thing until you showed us PALER.

I couldn’t get the idea of all this debit and credit jazz and assets and whatever until we were shown PALER.

PALER helped me work out what goes where and made accounting easy.

Negative comments from students from the previous use of PALER included the following:

I got confused in the exam with the arrows.

Took me longer to get debits and credits in the exam. . .needs to be easier way.

Comments from students from the previous use of ALORE included the following:

ALORE was so much easier to follow than PALER.

ALORE was a great thing for me now I get it.

“Hey face it ALORE is better than PALER it’s just so much more simple.

These comments suggest that both devices have proven to be useful learning tools, with ALORE purportedly being simpler and easier to apply. However, there was no evidence to substantiate the claims that they were useful learning tools in general or that one device promoted learning at a greater level than the other. To test the usefulness of these devices in the learning of accounting and to compare the efficacy between the two devices, an experiment was conducted.

This research contributes to the literature by empirically testing the use of mnemonic devices within the accounting discipline, as well as examining the difference between two mnemonic devices being used to teach the same knowledge and enhance learning. The study makes a further contribution with regard to the use of mnemonic devices by presenting a model for assessing the potential strengths or weaknesses of the characteristics of memory cues in general. This model is the first step in addressing a major gap in the literature (Eysenck & Keane, 1995).

A pedagogical justification for the use of mnemonic de-vices is based on the literature, which suggests that such devices can contribute to student learning and aid in the de-velopment of cognitive skills. Students who participated in the experiment were therefore expected to exhibit greater un-derstanding and ability in applying the accounting principles. These expectations lead to the formulation of the following null hypothesis (H0).

H0a: There would be no difference in the ability to cor-rectly answer basic accounting questions among the three groups prior to the introduction of the mnemonic device.

H0b: There would be no difference in the ability to cor-rectly answer basic accounting questions among the three groups after the introduction of the mnemonic de-vice.

H0c: There would be no difference in the ability to correctly answer basic accounting questions between the two treatment groups after the introduction of the mnemonic device.

METHOD

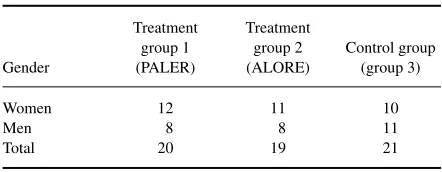

A total of 59 introductory accounting students participated in the experiment as a tutorial exercise. The experiment was divided into three groups containing 20, 18, and 21 students, respectively, in the tutorial groups (see Table 1). A 2×3 factorial design was used with learning strategy (PALER, ALORE, and control group with no mnemonic) and applica-tion as between-participant factors.

Mnemonic Device Conditions

Students were first tested to assess their basic knowledge of accounting issues. The pretest instrument consisted of a short set of multiple-choice questions, which took 5 min.

EMPIRICAL TEST OF MNEMONIC DEVICES 353

TABLE 1

Demographic Data for the Groups

Group 1 2 3

Device PALER ALORE Control

Students 20 19 21

Following the pretest, students were then introduced to the mnemonic device and taken step by step through its appli-cation. Discussion focused on the relevance in answering set homework questions, which occurred over a period of 30 min. Having completed the introduction, a posttest was implemented. This consisted of multiple-choice questions (some of which were similar in nature to the pretest) and ad-ditional question designed to illicit the use of the mnemonic device. The posttest was for a period of 10 min. The pre- and posttest instruments are provided in Appendixes C and D, respectively.

Control Group Condition

The control group condition followed much the same pattern of testing and instruction as did the mnemonic device groups, except that no mnemonic device was taught or mentioned during the 30 min of discussion on homework. The pre- and posttest instruments were identical in each group.

The Treatment Group 1 consisted of 12 (60%) women and 8 (40%) men, Treatment Group 2 consisted of 11 (58%) women and 8 (42%) men, and the control group had 10 (48%) women and 11 (52%) men (see Table 2). The three groups were compared using attest and were found not to be significantly different, for 1:2,t(37)=0.130,α=.897; for 1:3,t(39)=.781,α=.439; for 2:3,t(38)=.637,α= .528. Therefore, gender was not expected to affect the results of this study (Lipe, 1989; Lopus 1997).

The ages of the students in the three groups were collapsed into categories (Table 3). Comparisons were made using at

test, for 1:2,t(37)=.022,α=.983; for 1:3,t(39)=.568,α=

.573; for 2:3,t(38)=.556,α=.581, indicating that there was

no significant difference in the ages between the three groups.

RESULTS

The first null hypothesis involved comparing the results from the pretest between the three groups. For the purpose of

anal-TABLE 2 Age Groupings of Students

Age

ysis, the means of the student scores are reported. The pretest results as summarized in Table 4 reveal that the mean of the control group was higher than that of both the PALER group and the ALORE group. Analysis of the means and standard deviations were conducted using the student ttest and the results are presented in Table 5. The PALER treatment group did not perform better in the pretest than the control group. The ALORE treatment group did not perform better in the pretest than the control group. The PALER treatment group did not perform better in the pretest than the ALORE treat-ment group. Thettests reveal that there was no significant difference between the groups. Subsequently, the first null hypothesis could not be rejected. The finding is that there was no significant difference between the groups at the com-mencement of the tutorial.

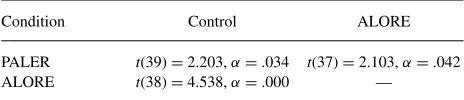

The second null hypothesis focused on the scores from the posttest as identified in Table 6 below. Analysis of the means and standard deviations were conducted using the student

t test and the results are presented in Table 7. The scores from the posttest for both treatment groups were significantly higher than for the control group. The PALER treatment group performed better in the posttest than the control group. The ALORE treatment group performed better in the posttest than the control group. The null hypothesis was therefore rejected.

The third null hypothesis focused on the difference be-tween the two treatment groups. The ALORE treatment group performed better in the posttest than the PALER treat-ment group refer to Table 7 for the result of thettest. The null hypothesis was therefore rejected.

TABLE 4

Pretest Scores as a Function of Learning Condition

Condition X¯ SD

PALER 2.00 0.973

ALORE 2.05 1.026

Control 2.10 0.995

TABLE 5

tTest Results Between Learning Conditions for Pretest Scores

Condition Control ALORE

PALER t(39)=–.310,α=.759 t(37)=–.164,α=.870 ALORE t(38)=–.133,α=.895 —

DISCUSSION

The pretest provided evidence that all three groups were relatively equivalent in their knowledge of accounting as there was no significant difference between their pretest scores. However, a difference was found between the treat-ment groups and the control group in the posttest scores. The treatment groups both achieved higher scores than the con-trol group in the posttest and these scores were found to be significantly different.

In addition, the ALORE treatment group performed better in the posttest than the PALER treatment group. The scores proved to be significantly higher when subjected to the t

test. This finding is consistent with the comments made by previous students and supports the claims that the mnemonic ALORE was simpler and easier to apply even under the stress and time pressures of the test.

Overall, the results of this study are consistent with prior research, which suggested that a mnemonic device would likely accelerate the rate at which new information is ac-quired (Levin & Pressley, 1985; Wang & Thomas, 1996). The time frame of the learning was restricted to the tutorial and the results indicate that both the mnemonic devices were influential in promoting learning. The results are also con-sistent with the findings of Levin and Levin (1990) that a mnemonic device could improve solving tasks involving for-mal reasoning. The posttest consisted of tasks that required formal reasoning.

There are a number of indications that the mnemonic de-vice is an effective learning tool, one that individuals are able to become comfortable with quickly. The findings provide ev-idence that instruction involving the use of mnemonic devices does enhance a student’s formal reasoning skills and that this has the potential for application of knowledge to more varied tasks. Instruction of elementary accounting principals at the university level has been shown to be strengthened by the use of mnemonic devices.

TABLE 6

tTest Results Between Learning Conditions for Post-Test Scores

Condition Control ALORE

PALER t(39)=2.203,α=.034 t(37)=2.103,α=.042 ALORE t(38)=4.538,α=.000 —

TABLE 7

Posttest Scores as a Function of Learning Condition

Condition X¯ SD

PALER 12.85 4.660

ALORE 15.63 3.483

Control 9.62 4.727

Finally, the model presented in this article offers an oppor-tunity to assess the strengths or weaknesses of existing mem-ory cues. In regard to the difference between the mnemonics ALORE and PALER, the stronger results for ALORE appear to be related the fewer number of steps and the simpler con-cept with regard to the identification of a debit or credit as a result of an increase or decrease. The strength of ALORE can be linked to the fewer memory constraints and that it is more intuitively easier to follow the organization of the information, which contributes to better retention and recall. This assessment is also supported by the comments made by the students. Future researchers using the model may pro-vide greater insight into the characteristics which contribute to one memory cue being superior or more effective than another.

NOTES

1. The mnemonic PALER was handed down by associate professor John Williams, and I have merely embel-lished its application for use in my teaching.

2. The mnemonic ALORE was handed down by Damian Ringelstein as an alternative and arguably more simple form of mnemonic.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J. (1980).Cognitive psychology and its implications. San Fran-cisco: Freemann.

Anderson, T., & Armbruster, B. (1984). Studying. In D. Pearson (Ed.),

Handbook of research in reading(pp. 657–679). New York: Longman.

Ausbel, D. (1963).The psychology of meaningful verbal learning. New York: Grune and Stratton.

Bourne, L. E., Dominowski, R. L., Loftus, E. F., & Healy, A. F. (1986). Cognitive processes(2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Bower, G. H. (1970). Organizational factors in memory.Cognitive

Psychol-ogy,11, 177–220.

Brown, R., & McNeil, D. (1966). The “tip of the tongue” phenomenon, Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behaviour,5, 325–337. Carroll, W. (1994). Using worked example an instructional support in

alge-bra classroom.Journal of Educational Psychology,86, 360–367. Craik, F. I., & Lockhart, R. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for

memory research.Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior,11, 671–684.

Debowski, S., Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (2001). Impact of guided exploration and enactive exploration on self-regulatory mechanisms and information

EMPIRICAL TEST OF MNEMONIC DEVICES 355 acquisition through electronic search.Journal of Applied Psychology,86,

1129–1141.

Ericsson, K., & Polson, P. (1988). An experimental analysis of the mecha-nisms of a memory skill,Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning,

Memory and Cognition,14, 305–316.

Eysenck, M. W., & Eysenck, M. C. (1980). Effects of processing depth, distinctiveness, and word frequency on retention.British Journal of Psy-chology,71, 263–274.

Eysenck, M. W., & Keane, M. (1995).Cognitive psychology: A student’s handbook, (3rd ed.). Hove, England: Psychology Press.

Facione, N., & Facione, P. (2008). Critical thinking and clinical judgement. In N. Facione & P. Facione (Eds.),Critical thinking and clinical reasoning

in the health sciences: A teaching anthology(pp. 1–13). Milbrae, CA:

Insight Assessment and California Academic Press.

Joyce, B., & Weil, M. (1986).Models of teaching(3rd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Gal, I., & Garfield, J. (1997). Curricular goals and assessment challenges in statistics education. In I. Gal & J. Garfield (Eds.),The assessment challenge in statistics education(pp. 1–13). Amsterdam: IOS Press. Gumar, J., & Martin, D. (1990). Group ethics: A multimodal model for

training knowledge and skill competencies. Journal for Specialists in Group Work,15, 94–103.

Hoggett, J., Edwards, L., Medlin, J., & Tilling, M. (2009).Accounting in Australia(7th ed.). Brisbane, Australia: Wiley.

Kiewra, K. A. (1989). A review of note-taking: The encoding storage paradigm and beyond.Educational Psychology Review,1, 147–172. King, A. (1992). Comparison of self-questioning, summarizing and

notetakeing-review as strategies for learning from lectures. American Educational Research Journal,29, 303–323.

King, A. (1994). Guiding knowledge construction in the classroom: Ef-fects of teaching children how to question and how to explain.American Educational Research Journal,31, 338–368.

Kolb, D. A. (1984).Experiential learning: Experience as a source of learn-ing and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Levin, M., & Levin, J. (1990). Scientific mnemonics: Methods for max-imising more than memory.American Educational Research Journal,27, 301–321.

Levin, J., & Presley, M. (1985). Mnemonic vocabulary instruction: What’s fact, what’s fiction. In R. F. Dillon (Ed.),Individual differences in cogni-tion(Vol. 2, pp. 145–172). Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Lipe, M. (1989). Further evidence on the performance of female versus male accounting students.Issues in Accounting Education,4, 144–152. Lockavitch, J. F. (1986). Motivating the unmotivated student.Techniques,

2, 317–321.

Lopus, J. (1997). Effects of the high school economics curriculum on learn-ing in the college principles class.Journal of Economic Education,28, 143–153.

Mandler, G. (1980). Retrieval processing in recognition.Memory and Cog-nition,2, 613–615.

Marschark, M., & Hunt, R. (1989). A reexamination of the role of imagery in learning and memory.Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning,

Memory and Cognition,15, 710–720.

Miller, G. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits to our capacity for processing information.Psychological Review, 63, 81–97.

Miller, S., Peterson, S., & Mercer, C. D. (1993). Mnemonics: Enhancing the math performance of students with learning difficulties.Intervention in School and Clinic,29(2), 78–82.

Palinscar, A., & Brown, A. (1989). Instruction for self-regulated reading. In L. Resnick & L. Klopfer (Eds.), Toward the thinking curriculum: Current cognitive research(pp. 19–39). Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Piaget, J. (1972). Intellectual evolution from adolescence to adulthood. Hu-man Development,15(1), 1–2.

Pressley, M., Wood, E., Woloshyn, V., Martin, V., King, A., & Menke, D. (1992). Encouraging mindful use of prior knowledge: Attempting to

con-struct explanatory answers facilitates learning.Educational Psychologist, 27(1), 91–110.

Smeby, J. (1996). Disciplinary differences in university teaching.Studies in Higher Education,21(1), 69–79.

Sweller, J. (1999).Instructional design in technical areas. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Tuovinen, J., & Sweller, J. (1999). A comparison of cognitive load associated with discovery learning and worked examples.Journal of Educational Psychology,91, 334–341.

Wang, A., & Thomas, M. (1996). Mnemonic Instruction and the gifted child. Roeper Review,19, 104–106.

Webb, L. (2006). Learning by doing.Training Journal, March, 36–41. Wilding, J., Rashid, W., Gilmore, D., & Valentine, E. (1986). A

com-parison of two mnemonic methods in learning medical information.

Human Learning Journal of Practical Research and Applications,5,

211–217.

Woloshyn, V., Willoughby, T., Wood, E., & Pressely, M. (1990). Elaborative interrogation facilitates adult learning of factual paragraphs.Journal of Educational Psychology,82, 513–524.

Wood, E., Needham, D. R., Williams, J., Roberts, R., & Willoughby, T. (1994). Evaluating the quality and impact of mediators for learning when using associative memory strategies.Applied Cognitive Psychology,8, 679–692.

Appendix A

Accounting Mnemonic Device PALER

PALER refers to Proprietorship, Assets, Liabilities, Ex-penses, and Revenues. It is a useful tool for explaining the elements of accounting equation, the notion of debits and credits, and the principles of the basic accounting cycle.

Step 1, introduce the term, be sure to leave space at the beginning and between each letter!

Figure 1.

PALER Step 1

Step 2, introduce the concept of Debit and Credit and start with what happens with a Debit entry to one of the elements.

Figure 2.

PALER Step 2

Step 3, use arrows to indicate the effect that a debit would have to each of the particular elements.(What effect would posting a debit to each account have?) [A debit would reduce Proprietorship—increase an Asset etc.] Conversely the effect of a credit to each of the particular elements would have the opposite effect. [A credit would increase Proprietorship—reduce an Asset etc.]Following the direc-tion of the arrows up or down as the case may be.

Figure 3.

PALER Step 3

Step 4, explain that the arrows can be used to establish the nature of each element. (That is if a debit to the Propri-etorship account will reduce it—then logically—it must be the opposite sign—it must therefore be a credit by nature!) [Write the sign above each element to reinforce the concept!]

{It is also useful to point out at this time that the Proprietor-ship is a liability to the business, which is consistent with the separate entity concept!}

Figure 4.

PALER Step 4

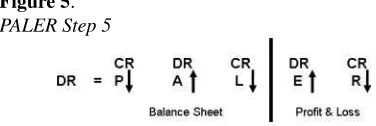

Step 5, draw a line between theLand theE, explain that this indicates the difference between Balance Sheet items and Profit & Loss or Income Statement items!(Revenue less Expenses equals profit or loss!)

Figure 5.

PALER Step 5

Step 6, explain that the Profit and Loss or Income State-ment items are temporary accounts which must be closed at the end of the financial period. (This reinforces the con-cept of accrual accounting, in that, the balance sheet rep-resents a particular point in time in contrast to the profit and loss or income statement which is for a period. The implication is that adjustments are required to compare the revenue earned in a period with the costs associated with earning that revenue. Finally, the profit or loss goes to the owner this is further confirmation that the Proprietor-ship account is a credit, since both revenue and profit are credits!)

Figure 6.

PALER Step 6

Appendix B

Accounting Mnemonic Device ALORE

ALORErefers to Assets, Liabilities, Owners’ Equity, Rev-enues, and Expenses. It is also a useful tool for explaining the elements of accounting equation, the notion of debits and credits, and the principles of the basic accounting cycle. The additional benefits associated with this mnemonic are that it is simpler to recall having greater relevance to the accounting equations that underpin the Balance Sheet and the Income Statement.

Step 1, introduce the term, be sure to leave space at the beginning and between each letter!

Figure 7.

ALORE Step 1

Step 2, introduce the concept of Increasing the value of an element using Debits and Credits! In effect, identify whether a debit (DR) or credit (CR) will increase the type of account. Students find this is easier to remember particularly when it is pointed out to them that the first and last letter only are debit (DR) accounts and therefore the three in the middle are credit (CR) accounts. This also explains the nature of each element that is whether it should have a debit or credit balance.

Figure 8.

ALORE Step 2

Step 3,introduce the concept of what would be required to decrease an element! In effect the converse of what is required to increase an element. The students report that this is much more logical than the use of arrows as required in the PALER approach.

Figure 9.

ALORE Step 3

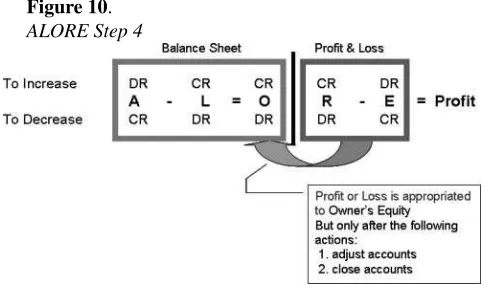

Step 4,draw a line between theOand theR, explain that this indicates the difference between Balance Sheet items and Profit and Loss or Income Statement items!(Revenue less Expenses equals profit or loss!)

The juxtaposition of the R (revenue) and E (expenses) and the repositioning of the Owner’s Equity is far more con-sistent with the accounting equations. Specifically, Assets minus Liabilities equals Owner’s Equity and Revenue minus Expenses equals profit.

EMPIRICAL TEST OF MNEMONIC DEVICES 357 Figure 10.

ALORE Step 4

Appendix C

Pretest

Multiple-choice questions:

In accounting, debit entries to a general ledger account cause:

a) Increases in owners’ equity, decreases in liabilities and increases in assets.

b) Decreases in liabilities, increases in assets, and decreases in owners’ equity.

c) Decreases in assets, decreases in liabilities, and increases in owners’ equity.

d) Decreases in assets, increases in liabilities, and increases in owners’ equity.

Which of the following accounting procedures requires the greatest knowledge of generally accepted accounting principles?

a) Journalising business transactions.

b) Posting Journal entries to General Ledger accounts. c) Preparing a Trial Balance.

d) Locating errors in a Trial Balance.

The purchase of office furniture on account (credit) is recorded as:

a) Debit Office Furniture, Credit Cash at Bank. b) Debit Accounts Receivable, Credit Office Furniture. c) Debit Office Furniture, Credit Owners’, Capital. d) Debit Office Furniture, Credit Accounts Payable.

Which of the following is not a transaction?

a) The Owner contributes$50,000 to start the business. b) Office Furniture is purchased on credit for$15,000.

c) A Sales Assistant is hired at$400 a week to commence next week.

d) Paid$2,000 for two months rent in advance.

The recording of a sale to a customer on account is recorded as:

a) Debit Sales Revenue, Credit Cash at Bank. b) Debit Accounts Receivable, Credit Sales Revenue. c) Debit Accounts Receivable, Credit Owners’, Capital. d) Debit Sales Revenue, Credit Accounts Payable.

Appendix D

Posttest

Part A–Multiple-choice questions:

In accounting, debit entries to a general ledger account cause:

a) Decreases in liabilities, increases in assets, and decreases in owners’ equity.

b) Increases in owners’ equity, decreases in liabilities and increases in assets.

c) Decreases in assets, increases in liabilities, and increases in owners’ equity.

d) Decreases in assets, decreases in liabilities, and increases in owners’ equity.

The purchase of a computer on account (credit) is recorded as:

a) Debit Computer, Credit Owners’, Capital. b) Debit Computer, Credit Cash at Bank. c) Debit Accounts Receivable, Credit Computer. d) Debit Computer, Credit Accounts Payable.

Picard Refreshments had the following transactions in the month of April.

• J. Picard started the business by depositing$100,000 cash in the business bank account.

• Purchased $50,000 of equipment by paying a $20,000 cheque and agreed to pay the remainder with in 60 days (on credit account).

• Paid$13,000 on the amount owing for the equipment. • J Picard withdrew$2,000 cash from the business for his

personal use.

From the above information answer the following ques-tions.

What is the balance in the J. Picard, Capital Account at the end of April?

a) $98,000 b) $115,000 c) $100,000 d) $102,000

What is the balance in the General Ledger Cash at Bank Account of the business as at the end of April?

a) $100,000 Debit b) $65,000 Debit c) $65,000 Credit d) $80,000 Credit

What is the balance in the General Ledger Equipment Account of the business at the end of April?

a) $50,000 Credit b) $33,000 Debit c) $50,000 Debit d) $17,000 Credit

Part B–General Ledger Accounts:

Below is a list of general ledger accounts for Damian Interiors, followed by a series of transactions. Indicate the accounts that would be debited and credited to record each

transaction by placing the appropriate account number (or numbers) in the space provided. (note more than one account may be either debited or credited!)

1 Cash 5 Office Equipment 2 Accounts Receivable 6 Bills Payable 3 Land 7 Accounts Payable 4 Buildings 8 Damian’s, Capital

Transaction Account(s) Debited

Account(s) Credited Damian invested cash in the

business.

Received payment from a client for money owed on account.

Purchased Land and Building, paying a deposit and signing a Bill Payable for the balance owing. Sold an item of office

equipment at cost, received a deposit in cash and balance to be paid in 60 days on account.

Paid amount owing on account. Purchased Office Equipment

on account.