Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI Date: 12 January 2016, At: 17:49

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

"Teach Us to Learn": Multivariate Analysis of

Perception of Success in Team Learning

Ali Rassuli & John P. Manzer

To cite this article: Ali Rassuli & John P. Manzer (2005) "Teach Us to Learn": Multivariate Analysis of Perception of Success in Team Learning, Journal of Education for Business, 81:1, 21-27, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.1.21-28

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.1.21-28

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 79

View related articles

ABSTRACT. Considerable attention

has been given to the efficacy of

team-learning pedagogy, yet the

methodolo-gy remains underused among educators

in institutions of higher education. We

suggest that the perception of success

is antecedent to greater acceptance and

use of this teaching style. Educators

and students alike must experience the

value creation potential of team

learn-ing before they will endorse it. In this

article, the authors investigated

percep-tions of success within the theoretical

realms of cognition elaboration,

effec-tive collaboration, and motivation

per-spectives. In addition to rank-ordering

the importance of these realms, the

authors make recommendations and

suggest policies to raise the likelihood

of success in team-learning practice.

he superiority of the cooperative learning method over the traditional lecture style of teaching is well estab-lished in the literature. The basic tenets of cooperative learning are inter-group positive interdependence and individual accountability (Cottell & Millis, 1993; Slavin, 1992). Most scholars support the proposition that group-based instruction-al methods can be used to promote the achievement of desirable learning out-comes in institutions of higher education. To be specific, researchers advocated team-learning pedagogy as the main delivery scheme. Maier and Keenan (1994) described team learning as “a large number of structured, systematic in-class techniques that engage students in group work toward a common goal” (p. 358).

Despite decades of research on team learning and an overwhelming consensus on team-learning efficacy, its use in col-leges and universities is limited. Research by Becker (1997) showed an absence of team-learning techniques “in all economics courses at research univer-sities” (p. 1354). Hernandez (2002) reported that students resisted participat-ing in team-learnparticipat-ing activities. Raven-scroft, Buckless, McCombs, and Zucker-man (1995) and Imel (1999) similarly discussed teachers’ reluctance to employ team-learning methods in their classes.

In search of a successful formula for team learning, researchers have

concen-trated on a variety of structures and techniques. For example, Karp and Yoels (1987) concentrated on students’ group participation optimization, John-son, JohnJohn-son, and Smith (1991) stressed skill heterogeneity in the group, Fiecht-ner and Davis (1992) suggested a mini-mum allocation of grades to teamwork, Li Wan Po (1994) emphasized inclusion of an employer practicum in team activities, and Bartlett (1995) discussed free-rider problems. Also, Tanner and Lindquist (1998) researched the rela-tionship between attitude formation and performance. Many authors have even suggested detailed processes for admin-istration of team learning. Examples include Cottell and Millis (1993), Her-nandez (2002), Michaelsen and Black (1994), Michaelsen, Fink, and Knight (1997), and Persons (1998).

We suggest raising the likelihood of success is antecedent to promoting the use of team-learning pedagogy in insti-tutions of higher education. In this arti-cle, we redefine “success” in terms of student perceptions. Perceptions were measured using the academic achieve-ment theoretical perspectives proposed by Springer, Stanne, and Donovan (1999): (a) motivational, (b) affective, and (c) cognitive. These perspectives are based on the proposition that what students learn is influenced by how and why they learn. Once they experience its value creation potential, both

stu-“Teach Us to Learn”: Multivariate Analysis

of Perception of Success in Team Learning

ALI RASSULI JOHN P. MANZER

INDIANA UNIVERSITY–PURDUE UNIVERSITY FORT WAYNE (IPFW) FORT WAYNE, INDIANA

T

dents and faculty will be more amenable to team learning.

Review of the Literature

Traditional Teaching Versus Cooperative Learning

The shift from a teacher-focused method to a learner-focused approach came about as a result of a major para-digm shift from teaching to learning in the past few decades (Saunders, 1997). Now, most educators involved in higher education agree that the traditional ped-agogy of teaching does not lend itself to the creativity and problem-solving abil-ity that are expected of learners. Under the traditional method of teaching, the instructor is considered the source of “ultimate truth,” whose skill in dissemi-nating knowledge is derived from the ability to perform well on the classroom stage. Students are expected to learn more only if the professor does a better job of delivering materials through pro-fessing with “style” to a captive audi-ence (Michaelsen & Black, 1998). In the traditional setting, students are pas-sive listeners; yet, they are expected to possess extraordinarily long attention spans, retention skills, powerful imagi-nations, and, most important, excellent memories, to regurgitate that knowledge and prove their success by passing an examination. A number of scholars in various business as well as nonbusiness disciplines have abandoned the preoc-cupation of educators in favor of improving their own performance, alone in the classroom. The bias toward improving information delivery meth-ods rather than spending time develop-ing students’ learndevelop-ing has been docu-mented, for example, by Becker (1997), Brown (1997), Chonko (1993), Guskin (1994), and Johnson et al. (1991).

The main thrust of the new paradigm is a shift of focus on student and learner development. To effectively enhance learning skills, Slavin (1980) argues that students must be closely involved in the learning process. Johnson et al. (1991) emphasize the greater need for direct and active student involvement in the class-room. The new concept of involving stu-dents in the learning process calls for a major change in the traditional role of the

instructor. In the new paradigm, the teacher becomes a facilitator for learning. According to Bobbitt, Inks, Kemp, and Mayo (2000), instructors “should be the designers of a learning environment in which students are active participants in the learning process” (p. 15).

Active participation in learning is not confined to taking notes or raising a hand and responding to questions, and neither is paper presentation. It is accomplished through cooperative learning with group activities. The effective pedagogy in cooperative learn-ing is teamwork. Becker (1997, p. 1360) describes the team-learning process as “think, pair, and share.” In this process, students discuss, refine, and articulate issues posed in class and provide a team response in collaboration with each other. The main idea is that within the psychological safety of the team (Edmondson, Bohmer, & Pisano, 2001) of cooperative and responsible peers, a deeper level of thinking takes place (Knabb, 2000). In the process of sharing and communicating their thoughts, stu-dents develop a kind of collective learn-ing synergy that surpasses the sum of their individual efforts (Mutch, 1998).

Team-Learning Pedagogy

The primary focus of team learning is to fashion a learning environment and process where students are active-ly involved in learning. There is a com-mon understanding acom-mong scholars of the required elements of team teach-ing. Cottell and Millis (1993) argue for five features as requisites for a suc-cessful team-learning experience: (a) student interdependence, (b) individual accountability, (c) appropriate group-ing, (d) social skills interaction, and (e) group monitoring.

The debate is on how extensively to apply these elements in the classroom. The purpose is to foster a learning envi-ronment conducive to group interaction. Stringency of team rules, and the extent to which they are implemented, is the core difference between cooperative and collaborative styles of team learning. The main tenet of collaborative learning is achievement of higher levels of learn-ing through the intellectual efforts of students, or students and instructors

together (Smith & MacGregor, 1992). This is accomplished primarily through positive interdependence and individual accountability (Slavin, 1989). Collabo-rative learning methods are unstruc-tured, and students usually establish rules. For example, students determine group membership, rules of engage-ment, and procedures for contributions and accountability.

If we envisage collaborative learning as the initial position of a stringency scale continuum, cooperative style would appear on the opposing pole. Cooperative style is defined as “a large number of structured, systematic in-class techniques that engage students in group work toward a common goal” (Maier & Keenan, 1994, p. 358). In such a setting, the instructor generally controls the teams’ functions through a set of predetermined policies and activ-ities. As such, team goals are well defined, the instructor selects team members and assigns them to interrelat-ed roles, length of debates and problem-solving activities is monitored, and each team member is held accountable for his or her contribution to team and individ-ual learning.

As Springer et al. (1999) point out, “the many forms of cooperative and col-laborative small-group learning do not follow from a single theoretical per-spective” (p. 24). Divergent methods and variable results from empirical studies reflect this fact. Lancaster and Strand (2001) summarize the results of 10 team-learning studies in the area of accounting and report diametrically dif-ferent outcomes. These mixed results are symptomatic of the preponderance of discipline-specific studies. In their quest for a successful formula, scholars experiment with a variety of strategies. For example, Johnstone and Percival (1976) suggest limiting classroom lec-tures to a maximum of 18 min in chem-istry classes. Bobbitt et al. (2000) favor combining lectures with real-world events to improve learning in marketing theory classes. Ravenscroft et al. (1995) contend that, in addition to group grades, individual test scores must be assigned in accounting classes to further motivate team efforts for a more posi-tive outcome. Although proclaiming the usefulness of team-learning pedagogy,

Johnson, Johnson, and Stanne (2000) correctly point out the impossibility of devising a unique, effective method across educational disciplines.

Research

According to Lancaster and Strand (2001), learning models are not trans-ferable across educational disciplines; they asserted that “what works for one teacher in a particular situation may not work for another in a similar or different situation” (p. 554). Team-learning activ-ities can take a number of forms, limit-ed only by the creativity of the instruc-tor. In this study, we are searching for a common ground for team-learning suc-cess, beyond the pedagogical differ-ences. We posit that although there is no guarantee of consistently desirable out-comes, a better understanding of the determinants of team-learning effective-ness will improve the likelihood of achieving preferred outcomes.

Springer et al. (1999) articulated three interrelated theoretical perspec-tives to describe the “efficacy of small-group learning” (p. 24). The first is Cog-nitive Elaboration. They contended that new information is best retained when linked to information already present in memory. By describing and elaborating on classroom issues, team members establish this necessary association.

The second perspective is Affective Collaboration. Here, the objective is to increase interaction among peers. This can be accomplished not just by afford-ing students an opportunity to commu-nicate, but also by stimulating a desire to participate and discuss and exchange ideas. Conversing about issues simulta-neously enhances learning for both the listener and the communicator. This facilitates the learning process, as long as students remain focused and are less restricted with rules of engagement.

Finally, the third perspective is Motiva-tion. If students value the success of the group, they will support each other indi-vidually and collectively to succeed. This requires that students view the process as cooperative instead of seeing it as com-petitive. The emphasis is on the necessity of individual accountability for learning, to motivate students to share ideas well beyond merely sharing correct answers.

For students to effectively partici-pate in team learning, they must feel rewarded by success. They must understand that success is a complex process, with high test scores compos-ing only a fraction of their expected performance. Equally important to stu-dents should be that their peers do well. This can be accomplished if each student makes a connection with the material prior to team activities, and then effectively communicates and helps peers to relate and comprehend it. After all, everyone can share knowl-edge and perform better together.

Instrument Development and Data Collection

The data for this study were collected from economic principles classes in a medium-sized, state-sponsored, region-al university in the Midwest. The Department of Economics is part of the School of Business, which is accredited by the Association to Advance Colle-giate Schools of Business (AACSB). The university promotes the individual attention given to students because of its small classes. Economics classes are generally capped at 35 students and are taught by experienced and academically qualified faculty.

The questionnaire was developed in three stages. First, students in a pilot group were asked to evaluate a group-learning experience. These results pro-vided a preliminary basis for a pilot instrument, which we field tested on three groups of four students each. Based on the field test results, we devel-oped and administered another instru-ment to an economic principles class for further refinements prior to using it with the classes actually involved in the study. We administered the finalized survey questionnaire to six economic principles classes within a three-semes-ter period.

Two instructors were involved in this study. Prior to the start of each semester, instructors coordinated their coverage, class activities, and procedures. Although a team cooperative learning approach was emphasized, the imple-mentation process included collabora-tive elements. The instructors handled the groups’ goals by defining

assign-ments, timing for lecture and team activities, grading, monitoring group activities, and assuring appropriate grouping (Cottell & Millis, 1993). The students determined group size, mem-ber roles, peer assessments, and modes of interaction. Moreover, the instructors acted as designers and observers by responding to questions, mediating problems, and providing immediate feedback to the teams.

The survey instrument was composed of three interrelated segments. The first contained twelve 5-point Likert-scale questions (from 5 = strongly agree to 1 =strongly disagree) asking about stu-dents’ perceptions of success in team learning. The students’ responses consti-tuted the latent roots for the three con-structs of Cognitive Elaboration, Affec-tive Collaboration, and Motivation, as suggested by Springer et al. (1999).

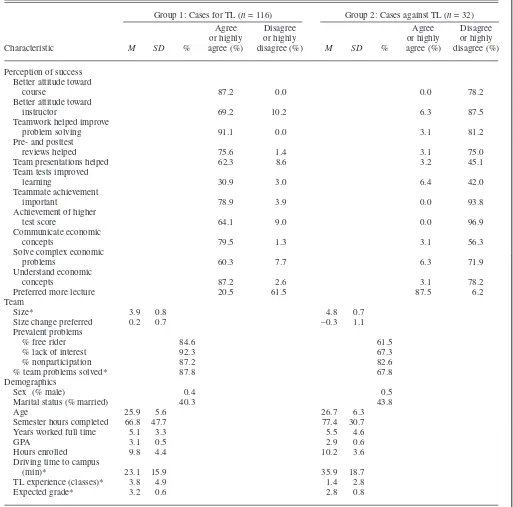

The second segment contained ques-tions regarding the optimal size of the team. Also included was a question intended to investigate the impact of group conflict resolution on perception of success. Finally, questions with regard to demographics appeared in the third seg-ment. In addition to demographics such as age, grade point average (GPA), gen-der, work status, and school status, as suggested by Hite, McIntyre, and Lynch (2001), other variables related to percep-tion of success: (a) prior exposure to teamwork, (b) expected course grade, and (c) opportunity costs of time com-mitment to team activities. For example, it is reasonable to assume that students exposed to team learning in prior courses appreciate the relationship between team activities and success. However, students with family responsibilities or full-time jobs may resent the time spent preparing for teamwork. A complete list of these variables appears in Table 1.

METHOD

The sample comprised 180 students from six economic principles classes. We asked students to rate, on a 5-point scale, the degree to which they agreed or dis-agreed with the statement that team-learning contributed highly to their mas-tery of the course material. Three subgroups emerged: (a) Group 1 includ-ed students who either agreedor highly

agreedwith that statement, (b) Group 2 was composed of students who either dis-agreed or highly disagreed, and (c) Group 3 encompassed students who gave neutral responses. Table 1 shows descrip-tive statistics for Groups 1 and 2. Because our objective was to assess the success of team learning, we accentuated the variance between groups by omitting the third group from Table 1.

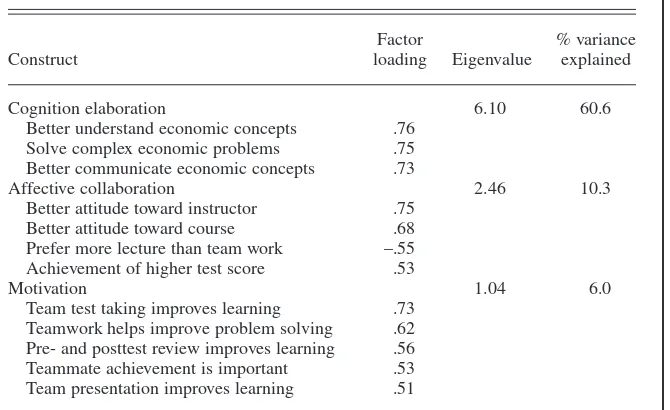

Further, to capture the team-learning perspectives proposed by Springer et al. (1999), we employed factor analysis. The multi-item constructs that satisfied two conditions—having eigenvalues of one or greater and explaining at least 5% of total variance—are included in Table 2. In addition, we computed Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for multi-item constructs used in this

study. They ranged from .79 to .92 and were found to be acceptable. Items that produced factor loadings of 50% or more constituted latent roots and were used to interpret each construct.

Finally, we used stepwise discrimi-nant analysis on team learning. Dis-criminant analysis is a statistical tech-nique that predicts group membership. We employed this technique for two

TABLE 1. Selected Descriptive Statistics on Team Learning (TL)

Group 1: Cases for TL (n= 116) Group 2: Cases against TL (n= 32)

Agree Disagree Agree Disagree

or highly or highly or highly or highly Characteristic M SD % agree (%) disagree (%) M SD % agree (%) disagree (%)

Perception of success Better attitude toward

course 87.2 0.0 0.0 78.2

Better attitude toward

instructor 69.2 10.2 6.3 87.5

Teamwork helped improve

problem solving 91.1 0.0 3.1 81.2

Pre- and posttest

reviews helped 75.6 1.4 3.1 75.0

Team presentations helped 62.3 8.6 3.2 45.1

Team tests improved

learning 30.9 3.0 6.4 42.0

Teammate achievement

important 78.9 3.9 0.0 93.8

Achievement of higher

test score 64.1 9.0 0.0 96.9

Communicate economic

concepts 79.5 1.3 3.1 56.3

Solve complex economic

problems 60.3 7.7 6.3 71.9

Understand economic

concepts 87.2 2.6 3.1 78.2

Preferred more lecture 20.5 61.5 87.5 6.2

Team

Size* 3.9 0.8 4.8 0.7

Size change preferred 0.2 0.7 –0.3 1.1

Prevalent problems

% free rider 84.6 61.5

% lack of interest 92.3 67.3

% nonparticipation 87.2 82.6

% team problems solved* 87.8 67.8

Demographics

Sex (% male) 0.4 0.5

Marital status (% married) 40.3 43.8

Age 25.9 5.6 26.7 6.3

Semester hours completed 66.8 47.7 77.4 30.7

Years worked full time 5.1 3.3 5.5 4.6

GPA 3.1 0.5 2.9 0.6

Hours enrolled 9.8 4.4 10.2 3.6

Driving time to campus

(min)* 23.1 15.9 35.9 18.7

TL experience (classes)* 3.8 4.9 1.4 2.8

Expected grade* 3.2 0.6 2.8 0.8

*p≤ .05 significant differences between group means.

reasons: first, to ascertain the predictive power of the constructs and variables used in this study; and second, to rank order their contribution to perceptions of team-learning success. The criterion variable was based on the student’s response to whether or not team learn-ing activities were extremely beneficial for mastery of the course. If they agreed

or strongly agreed(Group 1), the crite-rion variable was assigned a value of one. We assigned values of zero to respondents who either disagreed or

strongly disagreed with the statement (Group 2). We kept only significant dis-criminant predictors in the model by the stepwise procedure. We dropped insignificant predictors from the analy-sis, as they did not contribute to group membership predictability.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Selected results of descriptive statis-tics appear in Table 1. An overwhelming majority of students in Group 1 (87.2%) indicated they had a better attitude toward the course as a result of team-learning activities. In fact, none of them reported a worse attitude. A large major-ity of Group 1 also agreed that team-learning activities improved their per-formance. To be specific, they reported that teamwork had improved their prob-lem-solving abilities, as well as their ability to understand and communicate

complex economic concepts. Most of them reported developing a positive atti-tude toward the instructor, and only 20.5% preferred more lecture.

By contrast, an overwhelming major-ity of Group 2 (78.2%) revealed a nega-tive attitude, with none reporting any attitude improvement toward the course as a result of team-learning activities. An insignificant percentage of cases in this group reported improvement in learning, problem solving, understand-ing, or communicating economic con-cepts as a result of team learning. Final-ly, 87.5% of students from this group preferred more lecture as opposed to the team-learning method of instruction.

Analysis of team size and problems associated with working in a team were also revealing. Group 1, the group that favored team-learning, reported a team size of 4 (average = 3.9). They also noted the presence of major problems among team members, but they suggest-ed virtually no change in the size of the team. One may infer that the team func-tioned well, given the fact that the mem-bers were successful in solving 87.8% of team problems.

By contrast, Group 2 had a significantly larger team size of almost 5 (aver-age = 4.8). They preferred to reduce the group size, as appears in Table 1. The percentage of group problems reported by Group 2 was, in general, smaller than that reported by Group 1. However, the

members of Group 2 solved a significant-ly smaller percentage (67.8%) of team problems as compared with Group 1. Moreover, the percentage of nonpartici-pant (i.e., team problems) in Group 1 as compared with Group 2 was significantly higher. To determine if this problem was a result of a larger team size, we calculat-ed the correlation between the presence of nonparticipation problems with teams having more than four members. The bis-erial correlation coefficient produced a statistically significant value of .92.

Analysis of the demographics in Table 1 indicated that prior team-learning experience, driving time to campus, and expected grade were the only variables that differed significantly between groups. The group that found team learn-ing beneficial reported havlearn-ing experi-enced the team-learning method in more classes and expected to receive a higher grade in the course. It appears that the longer and greater involvement with team activities, the higher the chances for the realization of its positive contribution to students’ learning.

Results of factor analysis appear in Table 2. Cognition Elaboration is the first construct, with three items that relate to student perceptions concern-ing their mastery of course content and tools. Their understanding of basic economics concepts is an important aspect. If students believe they are mastering the underlying economic principles, they tend to feel more posi-tive toward the team learning method. Using this understanding of basic nomics concepts to solve complex eco-nomics problems reinforces a positive view of team learning. A related issue, and the third cognitive item, is the abil-ity to communicate economics con-cepts and issues. This reinforces per-ceptions of economics understanding and problem-solving skills. In a group learning setting, students must be able to communicate with each other to benefit from each other’s contribu-tions. Students with poor communica-tion skills, or those simply unwilling to communicate with fellow team mem-bers, frequently dislike the team-learn-ing method.

The second construct captures the Affective Collaboration perspective toward the team-learning method. Items

TABLE 2. Factor Matrix for Team-Learning Perspectives

Factor % variance

Construct loading Eigenvalue explained

Cognition elaboration 6.10 60.6

Better understand economic concepts .76 Solve complex economic problems .75 Better communicate economic concepts .73

Affective collaboration 2.46 10.3

Better attitude toward instructor .75 Better attitude toward course .68 Prefer more lecture than team work –.55 Achievement of higher test score .53

Motivation 1.04 6.0

Team test taking improves learning .73 Teamwork helps improve problem solving .62 Pre- and posttest review improves learning .56 Teammate achievement is important .53 Team presentation improves learning .51

Note. N= 180. Items with factor loadings ≥ .50 appear here.

that loaded on this construct involve stu-dent views of the teacher, course, instructional methodology, and their own test performance as assisting them to reach course objectives. Overall, these perceptions reveal student views of how effective team collaboration was in their advancement in the course. A positive view of the instructor might also enhance their outlook on team learning because they see instructor input as supportive. Insofar as students are concerned, attitudes in the class-room are an important consideration in shaping perceptions of the effectiveness of the team-learning method.

Motivation is the third construct. This construct grasps the essence of learning interdependence, interaction, and accountability among the team mem-bers as suggested by Cottell and Millis (1993). In a group setting, students not only learn from each other, they also reinforce each other’s learning process-es. Enhanced achievements through team test taking, problem solving, and presentation create strong motivation for camaraderie and responsibility for each other’s learning.

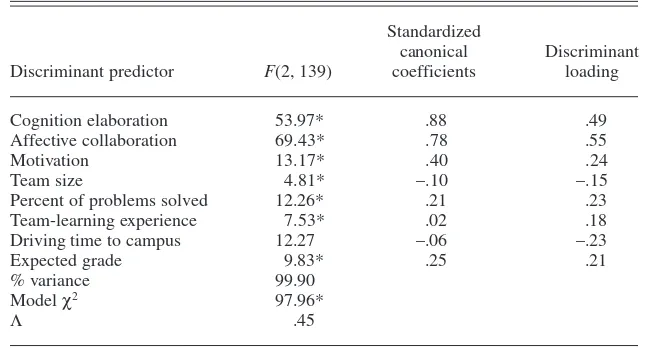

The results of stepwise discriminant analysis on team learning appear in Table 3. The discriminant function was statistically significant,χ2 (92,N= 148) = 97.96, and discriminating power (hit ratio) = 96.2%.

Table 3 also contains the standardized canonical coefficients (discriminant weights) of the stepwise discriminant analysis on team learning. Generally, the size of these coefficients is indicative of the relative importance of the predictive variables. However, ranking of their rela-tive importance is closely dependent on the intercorrelation between predictor variables. This problem (similar to the multicollinearity problem in regression) may cause interdependence among vari-ables, thus producing a blurred and unre-liable ranking of their relative importance. Such problems are generally avoided if the discriminant loadings (pooled within group correlations) are calculated and interpreted (Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black, 1998). Discriminant loadings rep-resent correlations between each predictor and the discriminant function and are most useful for interpretation of the results. They reveal that, among the vari-ables in the analysis, the three constructs have the strongest predictive power. If stu-dents feel that team learning in fact helps them perform better in the team and in the classroom, then they will vote in the affir-mative for the success of team learning.

Other interesting results are apparent from Table 3. A negative sign on team size indicates that students prefer a smaller team. Along with the positive sign on percentage of problems solved, these results corroborate the findings in

Table 1 and indicate that larger team size may render team problems unsolv-able, rendering teamwork dysfunction-al. Finally, the negative sign on driving time to campus is as expected for an urban commuter campus.

Conclusions and Implications

The literature on team learning gravi-tates unambiguously toward two conclu-sions: (a) It is an effective pedagogy and (b) despite its proven benefits, team learning remains underused in institu-tions of higher education. We suggest that raising the likelihood of success is antecedent to promoting the team-learn-ing pedagogy. Given the proposition that what students learn is influenced by how and why they learn, we redefine success in terms of student perceptions. Students must experience higher learning in forms other than the traditional, straight lecture approach, in which success is measured by examination scores. With the team learning method of instruction, students must perform well as team members in addition to passing exams.

Our study confirms that team activi-ties must be closely connected to pro-mote an environment in which motivat-ed students collaborate to learn. Basmotivat-ed on our findings, we emphasize the importance of rigor in teamwork issues and make specific recommendations for implementing this strategy.

Student input, discussions, presenta-tions, and the give-and-take of complex issues may carry parallel weight in the determination of a final grade. A posi-tive perception is further reinforced once students are convinced that they will achieve a higher level of compre-hension of course material by participat-ing in team activities.

First, instructors should realize that success comes in small increments through the interaction of students with-in the team. Instructors should develop as many techniques as possible for increasing student involvement. Howev-er, it is imperative that students do not feel they are engaging in “busy work.” Rather, assignments should be viewed as supportive of interdependence and geared to recognition of the students’ collective input toward mastery of course material. If students find the

TABLE 3. Results of Stepwise Discriminant Analysis on Preference for Team Learning (n= 148)

Standardized

canonical Discriminant Discriminant predictor F(2, 139) coefficients loading

Cognition elaboration 53.97* .88 .49

Affective collaboration 69.43* .78 .55

Motivation 13.17* .40 .24

Team size 4.81* –.10 –.15

Percent of problems solved 12.26* .21 .23

Team-learning experience 7.53* .02 .18

Driving time to campus 12.27 –.06 –.23

Expected grade 9.83* .25 .21

% variance 99.90

Model χ2 97.96*

Λ .45

Note. Insignificant discriminant predictors dropped from the analysis were sex, work experience, age, instructor, hours enrolled, semester hours completed, grade point average, and marital status. Hit ratio = 96.2% of observations where correctly classified.

*p ≤ .05.

methodology beneficial to their learning needs, they will develop a better attitude toward the discipline as a whole.

Second, instructors should monitor and assess teams and provide them with immediate feedback. The idea here, however, is not to police team activities. Perception of success is strengthened if the feedback reinforces cognitive elabo-ration, such as becoming more profi-cient with basic concepts, problem-solving abilities, and communicating economics concepts. Moreover, supply-ing feedback also presents an opportu-nity for instructors to stress the benefits of listening and learning from one another, resulting in accountability for student efforts to achieve success.

Third, team size should be limited to three or four students and carefully monitored for potential problems. Here again, aside from solving team person-ality or cultural conflicts, the instructor must also facilitate team operations to achieve cognitive and collaborative suc-cess. For example, students with prior team-learning experience tend to rein-force positive views of team-learning outcomes, as well as their view of mas-tering the material. For optimal results, these students should be appointed ini-tially as team leaders with responsibili-ties to team reporting tasks.

In addition, students with poor com-munication skills and a negative attitude toward team learning will need assis-tance in improving deficiencies. A secure team environment can foster a favorable outcome by providing stu-dents with opportunities to practice these skills with economics concepts in a comfortable setting. The most com-pelling reason for wide-scale use of the team-learning method is the success of the model in promoting positive atti-tudes toward mastery of the economic way of thinking.

NOTES

John P. Manzer passed away on August 8, 2005, as the result of an automobile accident.

Professor Ali Rassuli dedicates this article in memory of his friend and colleague, Professor John P. Manzer, a professional and highly regard-ed teacher of teachers.

REFERENCES

Barr, R. B., & Tagg, J. (1995). From teaching to learning: A new paradigm for undergraduate

students. Change, 27(6), 12–25.

Bartlett, R. L. (1995). A flip of the coin—a roll of the die: An answer to the free-rider problem in economic instruction. Journal of Economic Education, 26, 131–139.

Becker, W. E. (1997). Teaching economics to undergraduates. Journal of Economic Litera-ture, 37, 1347–1373.

Bobbitt, L. M., Inks, S. A., Kemp, K. J., & Mayo, D. T. (2000). Integrating marketing courses to enhance team-based experiential learning. Journal of Marketing Education,22, 15–24. Brown, G. (1997). Teaching psychology: A vade

mecum. Psychology Teaching Review, 2, 112–126.

Chonko, L. B. (1993). Business school education: Some thoughts and recommendations. Market-ing Education Review,1, 1–9.

Cottell, Jr., P. G., & Millis, B. J. (1993). Coopera-tive learning structures in the instruction of accounting. Issues in Accounting Education,8, 40–58.

Edmondson, A., Bohmer, R., & Pisano, G. (2001). Speeding up team learning. Harvard Business Review,79(9), 125–132.

Fiechtner, S. B., & Davis, E. A. (1992). Why some groups fail: A survey of students’ experiences with learning groups. In A. Goodsell, M. Maher, & V. Tinto (Eds.), Collaborative learning: A sourcebook for higher education (pp. 59–74). University Park, PA: National Center on Post-Secondary Teaching, Learning, & Assessment.

Guskin, A. E. (1994). Restructuring the role of faculty: Reducing student costs and enhancing student learning. Change,26, 16–26. Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. F., Tatham, R. L., &

Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Hernandez, S. A. (2002). Team learning in a mar-keting principles course: Cooperative structures that facilitate active learning and higher level thinking. Journal of Marketing Education,24, 73–85.

Hite, R. E., McIntyre, F. S., & Lynch, D. F. (2001). The impact of student characteristics on cooperative testing in the marketing classroom. Marketing Education Review,11, 27–34. Imel, S. (1999). Using groups in adult learning:

Theory and practice. The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions,19, 54–61. Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A. (1991). Cooperative learning: Increasing col-lege faculty instructional productivity (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Rep. No. 4). Wash-ington, DC: The George Washington University, School of Education and Human Development.

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Stanne, M. (2000). Cooperative learning methods: A meta-analysis. University of Minnesota. Retrieved July 1, 2000, from http://www.clcrc.com/ pages/cl-methods.html

Johnstone, A. H., & Percival, F. (1976). Attention breaks in lecture. Education in Chemistry,13, 49–50.

Karp, D., & Yoels, W. (1987). The college class-room: Some observations on the meanings of student participation. Sociology and Social Research,60, 421–439.

Knabb, M. T. (2000, March). Discovering team-work: A novel cooperative learning activity to encourage group interdependence. The Ameri-can Biology Teacher, 211–213.

Lancaster, K. A. S., & Strand, C. A. (2001). Using the team learning model in a managerial

accounting class: An experiment in cooperative learning. Issues in Accounting Education, 16(4), 549–567.

Li Wan Po, A. (1994). Brainstorming a pharmacy syllabus: Involving employers in curriculum design. In I. Sneddon & J. Kremer (Eds.),An enterprising curriculum: Teaching innovations in higher education(pp. 44–49). Belfast, Ire-land: HMSO.

Maier, M. H., & Keenan, D. (1994). Teaching tools: Cooperative learning in economics. Eco-nomic Inquiry, 32, 358–361.

Michaelsen, L. K., & Black, R. H. (1994). Build-ing learnBuild-ing teams: The key to harnessBuild-ing the power of small groups in higher education. In S. Kadel, & J. Keehner (Eds.),Collaborative learning: A sourcebook for higher education (pp. 65–81). State College, PA: National Cen-ter for Teaching, Learning, & Assessment. Michaelsen, L. K., & Black, R. H. (1998). A

work-shop on using small groups effectively. AAA Annual Meeting. New Orleans, LA: Continuing Professional Education.

Michaelsen, L. K., Fink, L. D., & Knight, A. (1997). Designing effective group activities: Lessons for classroom teaching and faculty development.In D. DeZure (Ed.),To improve the academy: Resources for faculty, instruc-tional and organizainstruc-tional development (pp. 373–397). Stillwater, OK: New Forums. Mutch, A. (1998). Employability or learning?

Groupwork in higher education. Education + Training,2, 50–56.

Persons, O. S. (1998). Factors influencing stu-dents’ peer evaluation in cooperative learning. Journal of Education for Business, 73, 225–229.

Ravenscroft, S. P., Buckless, F. A., McCombs, G. B., & Zuckerman, G. J. (1995). Incentives in student team learning: An experiment in coop-erative group learning. Issues in Accounting Education,10, 97–109.

Saunders, P. M. (1997, March). Experiential learning, cases and simulations in business communication. Business Communication Quarterly, 97.

Slavin, R. E. (1980). Cooperative learning. Review of Educational Research, 50(2), 315–342. Slavin, R. E. (1989). Cooperative learning and

student achievement. In R. E. Slavin (Ed.). School and classroom organization (pp. 129–156). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Slavin, R. E. (1992). Research on cooperative

learning: Consensus and controversy. In A. Goodsell, M. Maher, & V. Tinto (Eds.), Col-laborative learning: A sourcebook for higher education (pp. 97–99). University Park, PA: National Center on Post-Secondary Teaching, Learning, & Assessment.

Smith, B. L., & MacGregor, J. T. (1992). What is collaborative learning? In A. Goodsell, M. Maher, & V. Tinto (Eds.), Collaborative learning: A sourcebook for higher education (pp. 9–22). University Park, PA: National Cen-ter on Post-Secondery Teaching, Learning, & Assessment.

Springer, L., Stanne, M. E., & Donovan, S. S. (1999). Effects of small-group learning on undergraduates in science, mathematics, engi-neering, and technology: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research,69, 21–51. Tanner, M., & Lindquist, T. (1998). Using

MONOPOLY™ and teams–games–tourna-ments in accounting education: A cooperative learning teaching resource. Accounting Educa-tion,2, 139–162.