Deterrence, litigation costs, and the statute of limitations

for tort suits

Thomas J. Miceli

Department of Economics, U-63, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06269-1063

Received May 1999; received in revised form October 1999

1. Introduction

The conventional justification for a statute of limitations on tort suits (or any other legal claim) is that evidence deteriorates over time, thereby increasing the likelihood of legal error.1 The optimal statute balances this cost of a longer statute length against the dilution in deterrence that results from a shorter length. In this paper I develop a formal model to show that a finite statute length is optimal even in a world without the possibility of legal error. The trade-off involves only litigation costs and deterrence: while a shorter statute reduces deterrence, it also saves on litigation costs by limiting the number of suits that can be filed.

I examine this trade-off under both strict liability and under negligence, and show that the optimal statute length is (probably) shorter under strict liability than under negligence. Intuitively, the marginal benefit of lengthening the statute is higher under a negligence rule because, by increasing the length of time over which victims can file suit, deterrence is enhanced, which in turn reduces the likelihood that a given injurer will be found negligent. Thus, fewer victims file suits at each point in time because their chances of winning are reduced. As a result, litigation costs fall, which partially offsets the extra litigation costs when the statute is lengthened.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 sets up the basic model, Section 3 derives the

Tel. 860-486-5810; fax: 860-486-4463.

E-mail address:[email protected] (T.J. Miceli).

1See, e.g., Cooter and Ulen (1988: p. 155), Landes and Posner (1987: p. 307), and Epstein (1986). Despite (or possibly because of) the wide acceptance of this argument, there has been almost no formal analyses of statutes of limitations in the law and economics literature. An exception is Baker and Miceli (2000).

optimal statute of limitations for a strict liability rule, and Section 4 repeats the analysis for a negligence rule. Section 5 then offers some informal evidence in support of the theory based on the enactment of statutes of repose for products liability cases, the emergence of the rule of discovery under negligence law, and differences in the statute of limitations for trespass versus nuisance cases. Finally, Section 6 concludes.

2. The model

The model is based on the one developed by Hylton (1990). Injurers and victims are both risk-neutral, and injurers alone can take care to reduce the likelihood of an accident (i.e., the model is one of unilateral care). For simplicity, the injurer’s care choice is dichotomous: either take care or no care. Letq be the probability of an accident if the injurer takes care, andp be the probability if he does not, where p. q. 0.

The cost of care for injurers is denotedx, which varies across the population of injurers according to the distribution functionH(x).Injurers know their own cost of care, but victims do not observe the costs of individual injurers (though they know the distribution function), nor do they know if an injurer actually took care in a given case. However, I assume that the court can observe whether or not an injurer took care as well as the injurer’s cost of care (for purposes of applying a negligence rule) if a case goes to trial.

Victims vary in their (fixed) damages in the event of an accident, denoted D. The distribution function of victims’ damages is F(D).At the time they make their care choice, injurers do not know the damage that an individual victim will suffer, but they know the distribution of victim damages. However, the court can observe D after the fact when determining a damage award.

When an accident occurs, if the victim files suit, she incurs litigation costs ofcvwhile the injurer incurs litigation costs ofci.In Hylton’s (1990) static model, all victims who find a suit profitable file immediately. Here I allow the possibility that some victims will delay filing suit. For example, some injuries might not be immediately evident or some injurers might avoid immediate detection or identification. To keep the model simple, I abstract from the specific reason for delay and simply treat the length of time after an accident that a victim files suit, denotedt, as a random variable with distribution functionG(t).Thus, for example, if the statute of limitations is set atL, thenG(L) is the probability that a randomly chosen victim will file suit by time L.2

3. Strict liability

Under strict liability, all victims for whom D $ c

vand t #L will file suit. Thus, if an accident occurs, the probability of a lawsuit is g(t)[1 2 F(cv)] at any t up to L (where

g(t) [ G9(t)), and zero thereafter. If a suit is filed, the injurer faces liability equal to the damage suffered by the victim,D.For suits filed in the future (t.0), this amount should be discounted to the present (the date when the injurer makes his care choice) by the interest rate

r, yielding a present value of liability equal to De2rt for a suit filed at time t. I assume, however, that the court awards the victim interest onD at rater, beginning at the accident date (t50),3thereby exactly offsetting the injurer’s discounting. Thus, regardless of the date when a case is filed, the injurer bears expected liability of Das oft50. In the absence of this “prejudgment” interest, the injurer’s incentives would clearly be diluted merely by the victim’s delay in filing.4The same is not true of the injurer’s litigation costs. Specifically, a case filed at timetcosts the injurercie

2rt

in present value terms. Thus, the injurer does gain from delay in this respect.

Given the above factors, the injurer’s expected costs of taking care under a rule of strict liability with a statute of limitations of Lare given by

x1q$G~L!

E

Similarly, the expected costs of not taking care are

p$G~L!

E

Combining Eq. (1) and Eq. (2) yields the condition for the injurer to take care:

x#~p2q!$G~L!

E

The right-hand side represents the highest cost injurer who chooses to take care under strict liability as a function ofL. Taking the derivative of Eq. (3) with respect toLyields [Eq. (4)]

xs

Thus, increasing the statute of limitations increases the number of injurers who choose to take care, by increasing both expected liability and the present value of litigation costs. This captures the impact of the statute of limitations on deterrence.

Socially, care is desirable when the social costs of care are less than the social costs of no care. The social costs of care are

3I ignore the problem of possible differences between the discount rate and the interest rate.

x1q$E~D!1@12F~cv!#

E

This differs from Eq. (1) in two respects: the inclusion of damages suffered by victims who do not file suit, and the inclusion of the present value of the litigation costs of victims who do file. The social cost of not taking care are

p$E~D!1@12F~cv!#

E

which differs from Eq. (2) by the same factors.

Combining Eq. (5) and Eq. (6) shows that care is socially desirable when

x#~p2q!$E~D!1@12F~cv!#

E

The right-hand side of Eq. (7) represents the highest cost injurer for whom it is socially desirable to take care under strict liability. Comparing Eq. (3) and Eq. (7) shows thatxs*(L)

. xs(L) for any L, implying that strict liability underdeters (Hylton, 1990). This is true because, as noted above, injurers ignore the damages imposed on victims who do not file suit (i.e., those with D , cv), and the litigation costs of victims who do file.

We are now in a position to derive the optimal statute of limitations under strict liability. To do so, we first need to write down the expression for expected social costs. This is given by Eq. (5) weighted by the number of injurers who take care, H(xs(L)), plus Eq. (6) weighted by the number of injurers who do not take care, 1 2 H(xs(L)). The resulting expression, after rearranging, is given by

SCs~L!5p$E~D!1@12F~cv!#

E

The optimal statute of limitations is found by minimizing Eq. (8). The first-order condi-tion, after rearranging, is given by5

@12F~cv!#e2rL~ci1c

The left-hand side of Eq. (9) represents the marginal cost of an increase inL. It captures the increase in the present value of expected litigation costs whenL is increased by one period, where p(1 2 H(xs)) 1 qH(xs) is the probability of an accident, and [1 2 F(cv)]g(L) is the number of new cases filed in the event of an accident. The right-hand side captures the marginal benefit of an increase in L in terms of increased deterrence. The term xs/L

represents the increase in the threshold for care whenLis raised, which is weighted byh(xs), the fraction of injurers with cost of care equal toxs. The bracketed term represents the net savings in social costs when one more injurer takes care, where this term is positive due to the general underdeterrence under strict liability. According to Eq. (9), the optimal statute length balances the increased litigation costs from a longer statute against the increased deterrence benefits.

4. Negligence

Negligence differs from strict liability in that a victim will not recover against the injurer, even if she files in a timely manner, if the injurer took due care. Following Hylton (1990), we define due care by the Hand Rule,6which, in the current context, says that an injurer is negligent if he failed to take care andx,(p2q)E(D)[xH; that is, if his cost of care is less than the social benefit of care (xH) in a world of zero litigation costs.7The court can apply this rule because we assumed that it can observe the injurer’s care choice and cost of care after the fact.

Victims, however, cannot observe injurers’ costs of care, nor can they observe whether a given injurer has taken care at the time that they make their filing decision. Thus, they can at best calculate the probability that an injurer will be found negligent, given that an accident has occurred. Let this probability bew, which we will define below. Thus, victims for whom

wD $c

v andt# L will file suit under negligence. The probability of a suit, given that an accident occurs, is therefore g(t)[1 2 F(cv/w)] for any t # L, and zero thereafter.

Given the above, note that an injurer withx . xH will never take care because he will never be judged negligent by the court. Thus, only injurers with x # xH are “potentially

negligent” in the sense that they will be judged negligent if they failed to take care and the victim files suit following an accident. A potentially negligent injurer who takes care incurs expected costs of

x1q@12F~cv/w!#

E

0L

cie2rtg~t!dt. (10)

Thus, he incurs only the cost of care plus his expected litigation costs, given that he will be found non-negligent at trial. In contrast, when a potentially negligent injurer does not take care, his expected costs are

6See

U.S. v. Carroll Towing, 159 F.2d 169 (2d Cir. 1947).

p$G~L!

E

which includes expected liability plus litigation costs. Combining Eq. (10) and Eq. (11) gives the condition for the injurer to take care:

x#pG~L!

E

where the right-hand side is the highest cost injurer who chooses to take care under negligence.

We can now calculate the equilibrium value ofw, which, recall, is the probability that a given injurer will be found negligent, given that an accident has occurred. Since victims correctly anticipate the likelihood of a negligent verdict, we can use Bayes’ Rule to calculate

w~L!5 p@H~x

H!2H~xN~L!!#

p@12H~xN~L!!#1qH~xN~L!!. (13)

The numerator is the probability of an accident when the injurer does not take care times the probability that the injurer is both potentially negligent and fails to take care, while the denominator is the overall probability of an accident. Note that w is positive if and only if

xH .xN(L), implying that there are some injurers who are potentially negligent and fail to take care. Although this need not be true in general, it must be true in a negligence equilibrium.8

Assuming that an equilibrium exists, we can totally differentiate Eq. (12) and Eq. (13) and solve simultaneously to find the impact of varyingL on the equilibrium [Eq. (14)]:

xN L .0,

w

L,0. (14)

Intuitively, an increase in the statute of limitations increases the expected liability of injurers, thereby causing more injurers to take care (xN(L) increases), but because more injurers take care, the probability that a given injurer will be found negligent by the court (w(L)) decreases.

We now turn to social costs. When the injurer takes care, expected social costs are given by

x1q$E~D!1@~12F~cv/w!#

E

8The intuition is as follows. If all potentially negligent injurers take care, then

which is equivalent to (5) except thatcv/w replacescvas the lowest value ofD that results in a suit. When the injurer does not take care, expected social costs are

p$E~D!1@12F~cv/w!#

E

which similarly differs from Eq. (6). Combining Eq. (15) and Eq. (16) yields the condition for care to be socially desirable [Eq. (17)]:

x#~p2q!$E~D!1@12F~cv/w!#

E

where xN*(L) is the highest cost injurer for whom care is socially desirable under negli-gence. Note thatxN*(L) .xHdue to the absence of litigation costs fromxH. Further, since

xH . xN(L) for existence of a negligence equilibrium, it follows thatxN*(L) . xN(L), or that negligence, like strict liability,underdetersin equilibrium (Hylton, 1990).9

As above, the optimal statute of limitations under negligence minimizes expected social costs, which is given by Eq. (15) multiplied by the fraction of injurers taking care,H(xN(L)), plus Eq. (16) multiplied by the fraction not taking care, 1 2 H(xN(L)). After rearranging, this becomes

where, recall,w is a function ofL. Minimization of Eq. (18) yields the first-order condition

@12F~cv/w!#e

9The results of the analysis would therefore be unaffected if the due standard applied by the court is set at

xN

* rather than atxH

. However, use ofxH

greatly simplifies the model becausexH

is independent ofL, whereas

xN* is not. Moreover, there is no reason to believe that courts use

xN* rather than

Note that the first two terms of this condition resemble the two terms in Eq. (9) and have the same interpretation. Specifically, the term on the left-hand side of Eq. (19) is the marginal cost of a longer statute length in terms of increased litigation costs, while the first term on the right-hand side is the marginal deterrence benefits of an increased statute length. As was true under strict liability, greater deterrence is socially desirable because in equilibrium, negligence underdeters (as captured by the fact thatxN*(L)2xN(L).0). What is different here compared to strict liability is the second term on the right-hand side of Eq. (19), which is positive given that w/L , 0. This term captures an additional marginal benefit of increasing the statute length under negligence in the form of fewer lawsuits being filed in each period up to t 5 L. Intuitively, an increase in L lowers the probability that any given injurer will be judged negligent (given thatw/L ,0), thereby making lawsuits less profitable for victims. Note that this effect was absent under strict liability because that rule did not require victims to prove negligence by injurers as a condition for recovery.

The extra marginal benefit term in Eq. (19) suggests that the optimal statute length should be longer under negligence as compared to strict liability. This result cannot be established definitively because a comparison of the corresponding terms in Eq. (9) and Eq. (19) for any

Lis ambiguous. However, if these common effects are roughly offsetting, one would expect that the additional term in Eq. (19) would dominate, resulting in a longer statute length under negligence.

5. Applications of the analysis

The foregoing analysis suggests that one might try to test the model by asking whether the statute of limitations is longer in areas of tort law governed by negligence as compared to areas governed by strict liability. There are several problems in testing the model in this way. First, statutes of limitations are costly to change and therefore may respond only sluggishly to changes in relative costs and benefits. Second, economic theory maintains that the legal rule is itself an endogenous variable that should respond to changes in some of the same variables that affect the statute of limitations (e.g., litigation costs). Third, most torts are grouped under a single statute of limitations. Thus, for example, the shift in produces liability law from negligence toward strict liability during the twentieth century may have had no effect on the general statute length for personal injury cases. Despite these problems, I offer some evidence that the statute of limitations does in fact differ depending on whether a given area of the law is governed by strict liability or negligence. This evidence takes the form of variation in the rules that determine when the statute begins to run.10

Statutes of repose for products liability

As noted, one area of tort law that has shifted from negligence to strict liability is products liability.11 In response to this change, many states enacted “statutes of repose” for products liability suits (Peacock, 1993).12In contrast to a statute of limitation, which begins to run at the time an accident occurs, a statute of repose begins to run at the time the product in question was sold (Martin, 1982: p. 749). Thus, a statute of repose puts a predictable upper bound on the length of time that a manufacturer is at risk of suit from the sale of a particular product. A statute of limitation alone provides no such bound because it allows suits for accidents that occur long after sale as long as they are filed in a timely manner after the accident.

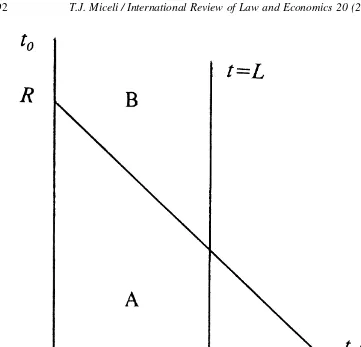

In the context of the model, it is easy to show that enactment of a statute of repose serves to reduce the expected number of suits that an injurer faces. In this sense, it is equivalent to a reduction inL. To see this formally, suppose that consumers purchase a dangerous product at timet50, and it causes an accident at timet0.0, which varies across consumers based on differences in use and random factors. Victims then file suit after a delay oftas described in the above model (i.e., a victim of an accident at timet0 files att0 1 t). Figure 1 shows all possible combinations oft0 andt, where each point represents a potential lawsuit.

In this amended model, the statute of limitations applies only to the delay in filing after occurrence of the accident. Thus, any suit witht# L is allowed to proceed, regardless oft

0. Graphically, the statute of limitations permits all suits to the left ofLin Figure 1 (i.e., areas A and B). In contrast, a statute of repose of lengthRapplies to the length of time following sale of the product, and therefore allows only those suits for whicht01t#R. Thus, victims in area B of Figure 1 will no longer be allowed to proceed, leaving area A as the set of products liability cases that satisfy both the statute of limitations and the statute of repose.

What this argument shows is that adding a statute of repose on top of a statute of limitations has the same effect as simply shortening the statute of limitations. Thus, the enactment of these statutes following the shift from negligence to strict liability for products liability suits seems to be consistent with the predictions of the model.

The discovery rule for negligence

Historically, a cause of action under negligence law began to run at the time that an injury actually occurred, or time t0 (the “damage rule”). Beginning in the area of medical mal-practice, however, courts and legislatures began to replace this with the “discovery rule,” under which “the statute does not begin to run until the negligent injury is, or should have been discovered.”13This rule has now become the majority rule for negligence cases.

The impact of the discovery rule is clearly to lengthen the statute of limitations by starting

11This evolution has been gradual, but Landes and Posner (1987: p. 307) roughly date the shift toHenningsen

v. Bloomfield Motors, Inc., 32 N.J. 358, 161 A.2d 69 (1960).

12Also see Martin (1982), who notes that as of 1982, as many as twenty-two states had enacted statutes of repose, ranging from six to fifteen years in length. Since then, however, many of these statutes have either been repealed or found unconstitutional (Warfel, 1991; Werber, 1995).

13See

it at a later date relative to the time of the injury. It therefore works in the opposite direction of a statute of repose, which we saw above begins the statute prior to the time of the injury. (Indeed, Keeton, et al. (1984: pp. 166 –167) observe that the enactment of statutes of repose was in part a response to the widening use of the discovery rule.) In combination, therefore, these two rules work in the predicted direction of effectively lengthening the statute of limitations for cases governed by negligence as compared to strict liability.

Trespass versus nuisance

The final application concerns the distinction between the torts of trespass and nuisance. Under trespass, the plaintiff is entitled to strictly enforce his or her right to exclusive possession of a piece of property. In contrast, the plaintiff can only assert a claim under nuisance law if the harm is both substantial and unreasonable, where the latter is based on a balancing of “the gravity of the harm and the utility of the conduct” (Keeton, et al., 1984: p. 630). Thus, trespass is governed by strict liability and nuisance by a negligence standard (Landes and Posner, 1987: p. 49).

It follows from the theory that the statute of limitations should be shorter for trespass as compared to nuisance, and this in fact appears to be the case. Specifically, under trespass, the statute of limitations begins to run “from the time of unlawful entry”14and “without regard to harm” (Keeton, et al., 1984: p. 70), whereas under nuisance, the statutory period does not begin to run “until some injury has been sustained.”15Once again, the law seems to conform to the predictions of the theory.

6. Conclusion

This paper has developed a formal model of statutes of limitations for tort suits based on the trade-off between deterrence and litigation costs. While a longer statute enhances deterrence by confronting injurers with more lawsuits, it increases litigation costs. The optimal statute length balances these effects at the margin. A notable feature of the model is that, in contrast to conventional arguments in favor of statutes of limitations, it does not rely on arguments about stale evidence and legal error as a basis for imposing a finite statute length.16

A key prediction of the model is that the optimal statute length appears to be longer under a negligence rule as compared to a strict liability rule. The reason is that, when the statute is lengthened, it increases incentives for care (deterrence), thereby making it harder for plaintiffs to prove negligence at trial. Thus, fewer cases are filed at any point in time, which lowers expected litigation costs. Since this benefit partially offsets the extra litigation costs incurred by lengthening the statute, the optimal statute is longer.

The paper concluded by suggesting that this prediction is consistent with variations in actual statutes of limitations. We first argued that the enactment of statutes of repose in the 1970s, which effectively shortened the statute of limitations for products liability suits, was a response to the shift from negligence to strict products liability. We next argued that adoption of the rule of discovery effectively lengthened the statute of limitations for negligence suits by delaying the start of the statutory period until the plaintiff discovers (or should have discovered) her injuries, rather than when she actually sustains them. Finally, we argued that the statute of limitations is longer for nuisance as compared to trespass actions, reflecting the reliance on negligence principles under the former and strict liability under the latter.

Acknowledgment

I acknowledge the helpful comments of an anonymous referee.

14See Am Jur 2d, Trespass, § 200 (1986). 15See Am Jur 2d, Nuisance, § 308 (1986).

References

Baker, M. & Miceli, T. (2000) Statutes of limitations for accident cases: theory and evidence.Research in Law and Economics, 19,47– 67.

Cooter. R. & Ulen, T. (1988).Law and Economics, New York: Harper-Collins.

Epstein, R. (1986). Past and future: the temporal dimension in the law of property. Washington Univ. Law Quarterly, 64,667–722.

Hylton, K. (1990). The Influence of litigation costs on deterrence under strict liability and under negligence.

International Review of Law and Economics, 10,161–171.

Keeton, W., Dobbs, D., Keeton, R. & Owen, D. (1984).Prosser and Keeton on Torts, 5th Ed., St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co.

Landes, W. & Posner, R. (1987).The Economic Structure of Tort Law, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press. Martin, M. (1982). A statute of repose for product liability claims.Fordham Law Review, 50,745–780. Ordover, J. (1978). Costly litigation in a model of single activity accidents.Journal of Legal Studies, 7,243–261. Peacock, M. (1993). An equitable approach to products liability statutes of repose.Northern Illinois Univ. Law

Review, 14,223–249.

Ross, K. & Goelz, D. (1985). The availability of prejudgment interest in tort actions. Journal of Products Liability, 8,79 – 87.

Warfel, W. (1991). Tolling of statutes of limitations in long-tail product liability litigation: the transformation of the tort system into a compensation system.Journal of Products Liability, 13,205–230.