Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2985135

Margin of Safety: Life History Strategies and the Effects

of Socioeconomic Status and Macroeconomic Conditions

on Self-Selection into Accounting

Justin Leiby*

University of Georgia

Paul E. Madsen

University of Florida

June 2017

*Corresponding Author 310 Herty Drive

255 Brooks Hall Athens, GA 30606 706.542.3596 [email protected]

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2985135 1

Margin of Safety: Life History Strategies and the Effects

of Socioeconomic Status and Macroeconomic Conditions

on Self-Selection into Accounting

Abstract: We use experimental and archival evidence to show that people who had low socioeconomic status (SES) as children participate in the U.S. accounting labor market in distinctive and consequential ways. Drawing on life history theory, we predict and show that low SES individuals select into accounting at disproportionately high rates relative to other fields, an effect driven by accounting’s relatively high job security. Supplemental tests are consistent with these low SES individuals being a source of high quality human capital for the accounting profession, as low SES individuals selecting into accounting possess desirable attributes at relatively high rates. From a social perspective, we provide theory and evidence consistent with accounting being an important and secure source of upward social mobility in comparison to other fields. However, recessions cause selection into accounting by low SES individuals to decrease at a higher rate than in other fields, compromising these professional and social benefits. For example, our evidence is consistent with the “low SES effect” improving gender diversity among entrants into the accounting labor market during good economic times. However, lower self-selection rates during recessions are particularly pronounced among low SES females, who may thus bear the brunt of lost professional and social benefits.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2985135 2

1. Introduction

In this study, we predict and show that people who had low childhood socioeconomic status

(SES)1 participate in the U.S. accounting labor market in distinctive and consequential ways. Accounting careers are relatively secure in that they reward relatively high human capital

investment with stable demand and returns (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2015; Madsen 2015). We

draw on life history theory, which concerns the relationship between childhood poverty and

adulthood preferences for security and deferred rewards (Chisholm 1993; Griskevicius et al. 2013),

to predict that low SES individuals 1) disproportionately select into accounting relative to other

fields, 2) possess attributes desired by the accounting profession, and 3) select into accounting at

disproportionately lower rates than other fields during times of macroeconomic uncertainty. Using

experimental and archival evidence, we find support for all three of these expectations.

Our theory and findings have important implications for society and for the accounting

profession. The United States has low socioeconomic mobility relative to other OECD countries

(OECD 2010; Blanden 2013; Mitnik et al. 2015). Even public universities, which graduate many

entry-level accountants, are marred by inequality (Chetty et al. 2017). From a social perspective,

our evidence suggests that selecting into accounting is an effective “ladder” out of poverty.

Relative to other fields, accounting delivers high wages, low wage variability, and high job

security, regardless of SES background, which facilitates upward mobility.

Our evidence further suggests that the accounting profession faces unique risks and

opportunities in the intensifying competition for talent (ACAP 2008; AICPA 2013). Despite

extensive research about accounting’s outputs (e.g., reported earnings), little theory or data exists

3

about accounting’s human capital inputs. Understanding entry-level labor supply is critical for

accounting due to its heavy reliance on young employees and early recruitment strategies (The

Economist 2014). Our theory and evidence suggest that this requires a nuanced understanding of

the preferences of low SES individuals. Driven by preferences for security and long-term human

capital returns, large numbers of talented low SES individuals select into accounting, which

benefits the profession. However, this effect reverses during recessions, during which desirable

low SES individuals disproportionately select away from accounting. Together, these findings

suggest an opportunity for the accounting profession to attract desirable individuals by

emphasizing the security and equal opportunity offered by accounting careers.

We test our research questions with multiple methods. For a controlled test of the

underlying cognitive mechanism, we first conduct an experiment that measures upper-division

accounting students’ intentions to enter the accounting profession, as opposed to common, less

secure alternatives such as finance. Our choice of participant group biases against observing

variation in intentions to enter accounting, as most participants have nearly completed accounting

degrees and have already had one or more internships with accounting firms. Prior to measuring

self-selection intentions, we actively manipulate cues of uncertain macroeconomic conditions by

priming half the participants with a narrative about the effects of recessions, while the other half

read a neutral prime (Griskevicius et al. 2011b). Following a neutral prime, intentions to self-select

into accounting are greater among low, as opposed to high SES individuals. Moreover, the

recession prime decreases intentions to self-select into accounting among low SES individuals, but

increases these intentions among high SES individuals. Consistent with our theorized mechanism,

the self-assessed importance of job security in a profession mediates the joint effect of SES and

4

We next test our research questions using large-sample archival data to demonstrate that

our theorized effects are broadly generalizable. We use data from the Higher Education Research

Institute’s (hereafter, “HERI") surveys on the demographics, degree choices, and families of

millions of college freshmen in the U.S conducted over several decades. In some supplemental

tests, we use a subset of HERI data describing college seniors. Consistent with our experimental

results, accounting disproportionately attracts low SES individuals relative to non-accounting

business fields and to all non-accounting fields.2 This effect holds among college seniors, as well. We also test this effect in recession years, as opposed to non-recession years. Consistent with our

predictions, selection into accounting by low SES individuals decreases in recession years, and

decreases more in accounting than in non-accounting business fields and all non-accounting fields.

Moreover, we conduct multivariate analyses that control for attributes desirable to the

profession, such as diverse demographics. We also gather input from a panel of partners and

managers at multiple public accounting firms about attributes most likely to distinguish successful

accountants, such as academic performance, motivation, and communication skills. Our findings

not only are robust to controlling for these attributes, but also show that low (as opposed to high)

SES individuals selecting accounting possess some of these attributes at higher rates. Low (as

opposed to high) SES individuals who select accounting are similar in academic ability and

motivation but exhibit greater gender diversity, self-confidence, and writing ability. This is

consistent with our theorized effect channeling quality human capital into the profession. This

finding is encouraging for social mobility, as other professional fields such as finance and law

systematically exclude low SES individuals (Rivera 2015).

5

However, our findings also show that recessions decrease low SES self-selection into

accounting more than into other fields. Thus, uncertain economic conditions undermine

accounting’s function as a means of upward mobility for disadvantaged people and undermine an

effect that otherwise channels high quality talent into the profession. In particular, our evidence

suggests that the low SES effect may be particularly effective in improving gender diversity by

attracting females from disadvantaged backgrounds to accounting. However, the recession effect

also disproportionately decreases selection into accounting by low SES females. If low SES

individuals benefit from selecting into accounting, then low SES females disproportionately miss

these benefits during uncertain macroeconomic times. While the low SES effect facilitates upward

social mobility, there may be a “gender gap” in its effects.

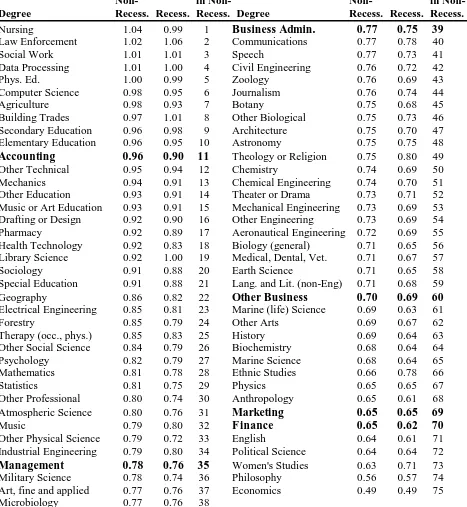

We next compare career outcomes in accounting to those in alternative fields. This analysis

can support our theory that accounting is a secure choice, and tests whether or not accounting both

delivers security and does so similarly for low and high SES individuals. We examine mean wages,

wage variance, and unemployment in accounting versus other substitute fields using data from the

National Survey of College Graduates (NSCG) by the National Science Foundation. The data

reveal that accounting degrees deliver high mean salaries with low variance, and unemployment

lower than in non-accounting business fields and all non-accounting fields. That is, if people select

accounting because they expect security, then accounting on average fulfills these expectations.

Moreover, the benefits of accounting are more pronounced among low SES individuals, especially

in comparison to finance, which is the most common alternative. This suggests that self-selection

into accounting is a secure choice that can have long-term welfare benefits for low SES individuals.

In sum, our evidence shows that accounting occupies a distinctive niche in the menu of

6

perceive it to be exceptionally safe. Accounting provides a relatively secure entry into a business

career for talented individuals from low SES backgrounds, which is encouraging in light of

evidence of persistent, implicit discrimination against low SES individuals in other professions

(Rivera 2015). Our evidence also suggests that accounting’s distinctive features benefit the

profession by attracting low SES people with attributes desired by the profession. Given the

profession’s (and accounting firms’) investments in broadening accounting’s appeal and

personalizing recruitment to best compete for talent (Jeacle 2008; Carnegie and Napier 2010), it is

inherently important to better understand the vector of attributes that influence a person’s interest

in accounting. Childhood SES is among these attributes.

We also contribute to broader theory on career selection and life history theory. We provide

the first empirical evidence of which we are aware that people are likely to have different life

history strategies that influence how they view their labor market options. Seminal economic

thinkers such as Alchian (1950) and Becker (1976) concurred that insights from evolutionary

biology enrich our understanding of economic choices. As Becker (1976, 818) observes, “the

approach of sociobiologists is highly congenial to economists, since they rely on competition, the

allocation of limited resources…efficient adaptation to the environment, and other concepts also

used by economists.” Career selection is part of the adaptive landscape of contemporary life, and

is thus well suited to interpretation through a life history theory lens. Our study illuminates the

cost / benefit tradeoffs that people make when they choose a profession by showing how and why

early life experiences shape the preferences that drive adult career choices.

2. Background Literature and Theory Development

The accounting profession’s sustainability depends on its capacity to attract human capital

7

better understand why people choose to become accountants. Prior literature provides limited

insight into this choice, mostly from exploratory studies of the personality profiles of accounting

students. The evidence suggests that accounting degree programs are dominated by a small subset

of personality types favoring concrete and analytical thinking (Oswick and Barber 1998; Wheeler

2001; Swain and Olsen 2012). In a longitudinal study, Swain and Olsen (2012) find that these

personality types disproportionately begin careers in accounting and remain in accounting jobs,

suggesting that accounting “fits” certain personalities. Also, relative to other fields, accounting

students are more conscientious and interested in making money, yet less creative and less

enthusiastic about their chosen field (Saemann and Crooker 1999; Allen 2004; Madsen 2015).

Blay and Fennema (2017) find that some college students exhibit inherent aptitude for accounting,

but this aptitude does not lead to self-selection into accounting. This suggests that self-selection

may reflect a more complex set of considerations than “personality fit” or inherent skills.

Indeed, we argue that the choice to become an accountant reflects a complex set of

cost-benefit considerations involving broad social and economic forces.3 In particular, identifying the forces that drive self-selection promotes a better understanding not only of the profession’s appeal

to labor market entrants, but also of how this appeal may change in different environments and

potentially of the profession’s broader societal function.

We focus on the impact of a person’s childhood SES on selection into accounting. SES is

important in itself due to its links to social welfare, as identifying professions that represent good

matches for low SES individuals can increase equality and upward socioeconomic movement. SES

8

also links to the diversity of human capital, which professions pursue but have achieved with mixed

success (Abbott 1988; Hammond 2002; Sullivan Commission 2004; Madsen 2013). In general,

low SES individuals confront social and economic barriers to professional success, as low SES is

associated with lower college attendance and higher college dropout rates (DeAngelo et al. 2011;

Chetty et al. 2017). Rivera (2015) reports that low SES college graduates are less likely than their

high SES counterparts to get jobs in elite law, banking, and consulting firms, even when they

graduate from the same institutions and have better grades. In addition to these barriers, low SES

is associated with lower emotional resilience to stress, further diminishing the likelihood of success

in higher education and in difficult jobs (Bowles et al. 2005). In one study of entry-level

accountants, low SES individuals perform as well as their high SES counterparts but exit at higher

rates (Collarelli et al. 1987). The authors offer no explanations for this finding, but it does raise

the possibility that low SES individuals are an underutilized source of quality human capital.

Moreover, this study focuses on SES because a person’s SES likely influences the appeal

of the accounting profession’s relative security, specifically its tradeoff between costs of entry and

relative security. Accounting requires significant investment in human capital, such as Bachelor’s

and sometimes Master’s degrees, certifications, and ongoing education. In turn, the accounting

labor market exhibits persistently low unemployment, stable demand that is robust to economic

conditions, and low wage variance (AICPA 2013; Bureau of Labor Statistics 2015).

We argue that SES affects self-selection into accounting by influencing the compatibility

between these fundamental attributes of accounting and a person’s broader life history strategy. In

the subsections that follow, we discuss life history strategies and the effect of SES on the

composition of the pool of potential entrants into accounting. Because a necessary condition of

9

examine the choice to attend college. As far as we are aware, no existing studies offer theoretical

explanations as to how this costly choice reflects a set of deeper fundamental life history

differences, particularly in low SES individuals. Our theory allows us to better define the potential

labor market entrants over whom accounting and other fields compete. Among this group of

potential entrants, we then examine the choice of accounting over other options.

2.1. Life History Theory and College Attendance

The idea of life history strategies originated in evolutionary biology. This theory seeks to

explain how organisms (including humans) trade off current versus future resource consumption

at different points in their lifespans (Schaffer 1983; Kaplan and Gangestad 2005). While early

applications of life history theory focused on tradeoffs to increase survival odds or reproductive

fitness, over the past two decades this theory has been applied more broadly to understand issues

in the social sciences, including in economics, marketing, psychology, and sociology. For

example, Wang and Dvorak (2010) draw on the theory’s biological roots to examine temporal

discounting, i.e., preferring smaller immediate payoffs over larger future payoffs. The authors find

that temporal discounting decreases in response to an experimental manipulation in which half of

participants consume a soft drink prior to the task—that is, temporarily increasing blood glucose

levels and the subjective sense that daily energy needs are fulfilled affects a common economic

tendency. This is one of many examples in which life history theory and its biological foundations

are useful to understanding contemporary psychological and economic issues.

For our study, career selection is well suited for examination as part of a life history

strategy, because selection is an action generally taken at a given point in the lifespan (i.e., early

adulthood) and involves complex tradeoffs affecting current and future resource acquisition and

10

usage at key points throughout life—such as pursuing post-secondary education versus working

full-time immediately after high school.

Life history strategies vary along a fast/slow continuum (Ellis et al. 2009). Slower (as

opposed to faster) strategies are consistent with longer over shorter horizons, prioritizing saving

over consumption, avoiding over accepting risks, among other distinctions (e.g., Kaplan and

Gangestad 2005; Griskevicius et al. 2013).4 The trajectory towards faster or slower life history strategies begins early in life, with harsher, more uncertain childhood environments—such as those

characterized by low SES or exposure to violence or disease—associated with a trajectory towards

faster strategies (Wilson and Daly 1997; Low et al. 2008; Brumbach et al. 2009; Ellis et al. 2009).5 For example, people from harsher childhood environments follow a faster life history trajectory in

adolescence and adulthood with riskier and earlier sexual activity, higher rates of smoking, and

lower impulse control (Seltzer and Oechsli 1985; Wilson and Daly 1997; Soteriades and DiFranza

2003; Hanson and Chen 2007; Nettle 2010; Hill et al. 2016). These effects extend to economic

decision making, as there are conditions in which people who grew up in harsher environments

have higher rates of credit card debt, are less willing to purchase insurance, and make riskier

investment choices, indicating faster life history strategies (Griskevicius et al. 2011b; 2013; Mittal

and Griskevicius 2016).

Life history theory allows us to develop nuanced predictions about the effect of SES on

selection into accounting. We begin by discussing the effect of low SES on the pool of potential

11

entrants into accounting, i.e., college attendees. Because lower SES implies a disadvantaged

position and thus an initially faster trajectory, having the option to pursue higher education

suggests that a low SES individual has deviated from that trajectory through a series of “slower”

choices as an adolescent. People from poorer backgrounds who have the option to attend college

likely made “slow” tradeoffs to invest in education, delay gratification, and avoid risks in

adolescence in order to overcome their disadvantaged initial position.

For example, Chen and Miller (2012) document a “shift and persist” life history strategy

among some low SES individuals, indicated by high resilience, optimism, and pride in one’s

achievements. Such resilience at younger ages is increasing in intelligence and self-esteem, and

helps low SES individuals manage stress and adapt to social circumstances at older ages (Masten

et al. 1990; Brody et al. 2013). This is consistent with evidence that low SES is positively

associated with pursuing a college education among those who exhibit resilience, e.g., by holding

jobs and demonstrating financial responsibility during adolescence (Brumbach et al. 2009).

Thus, we argue that, among college attendees, the distribution of life history strategies is

likely narrower when SES is low, because the initial advantages of high SES offer more wiggle

room for risky or myopic choices, yet retain opportunities such as higher education. Consequently,

college attendees are likely to have followed slower life history strategies than have non-attendees,

and this difference is likely to be significantly greater when SES is low. This enriches existing

literature, which generally observes that higher SES and educational attainment individually are

associated with positive health and life outcomes, but does not examine interactive effects.

We predict that the opportunity to choose to go to college likely signals that a person from

a poorer socioeconomic background has had a slower life history strategy in the past, as indicated

12

likely that pursuing college is a more credible signal of life history strategies among people from

poorer, as opposed to wealthier backgrounds. This leads to our first hypothesis,

Hypothesis 1: College attendees’ choices are more consistent with slower life history strategies than those of non-attendees, and this difference is greater for lower, as opposed to higher SES individuals.

2.2. Life History Theory and Self-Selecting into Accounting over Other Options

Among fields requiring a college education, choosing accounting over other options

represents a relatively slow strategy. Jobs in the accounting profession often require incremental

human capital investments, in the form of a master’s degree, certification (e.g., CPA, CMA), and

continuing professional education. In turn, accounting offers incremental short- and long-term

security in the form of low unemployment, stable demand, and salaries that deliver comparable

returns to other business fields (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2015; Madsen 2015).

Based on the development of hypothesis one, the set of potential entrants into the

accounting labor market comprises low SES individuals with predominately slow life history

strategies, in addition to high SES individuals who have a broader array of strategies. Thus, all

else equal, we predict that low SES is likely to increase the likelihood of self-selection of college

attendees into accounting—that is, low SES individuals will be disproportionately represented in

accounting relative to the set of all other fields. This leads to our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: Low SES individuals select into accounting to a greater degree than non-accounting business fields and all non-non-accounting fields.

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Recessions

The effect of SES on self-selection into accounting is likely to differ across good and bad

economic conditions. Although life history strategies develop early, they are not fixed and their

trajectories can change in response to cues in a person’s current environment (Griskevicius et al.

13

response to indicators of potential changes in resource availability or life expectancy (e.g.,

recessions, crime rates).

Childhood SES affects how people re-calibrate preferences based on environmental cues,

and does so throughout childhood and adulthood (Ellis et al. 2009; Griskevicius et al. 2011b).

Among adults, lower childhood SES is associated with lower perceived control over one’s

environment (Chen and Miller 2012; Mittal and Griskevicius 2014) and lower impulse control

capabilities (Kochanska et al. 2001; Hill et al. 2016). Also, low childhood SES is associated with

poor health outcomes among adults, and this association is driven by childhood SES but not

adulthood SES (Currie and Stabile 2003; Cohen et al. 2004; Hanson and Chen 2007). Hackman et

al. (2010) discuss evidence of biological and physiological differences between people who grew

up with low, as opposed to high SES. This includes fMRI evidence of different brain structures for

areas involved with problem-solving and threat detection.

In other words, people are physically and psychologically sensitized to the conditions that

they observe during childhood. If a person observes adverse conditions like resource scarcity while

making a key decision, then the person’s choice is likely to re-calibrate towards the trajectory

adopted in childhood, i.e., when facing adverse conditions, poorer (wealthier) backgrounds lead to

choices consistent with faster (slower) strategies.

Thus, we expect an interactive effect of SES and macroeconomic conditions on

self-selection into accounting. Although a person from a poorer background may have altered

trajectories during adolescence towards a slower strategy and investment in education, the

14

whether they make the choice in benign, as opposed to uncertain economic conditions.6 There is ample evidence to support this logic. In a series of experiments, Griskevicius et al. (2013) find that

people who grew up in poorer environments exhibit greater risk-taking and temporal discounting

when they observe cues of resource scarcity, as opposed to neutral cues. By contrast, these

behaviors decrease when childhood SES is high. Similarly, observing cues of current

environmental uncertainty decreases low SES individuals’ impulse control, willingness to delay

consumption, and willingness to purchase insurance, but has opposite effects among high SES

individuals (Griskevicius et al. 2011b; 2013; Mittal and Griskevicius 2014; 2016).

Applied to our setting, uncertain macroeconomic conditions like recessions are likely to

weaken preferences for the relatively slow attributes of accounting among those low SES

individuals who have already entered college and are, therefore, in the set of potential entrants into

accounting. That is, while low SES is likely to increase the preference for accounting in benign

economic conditions, it is likely to decrease this preference in uncertain macroeconomic

conditions. Thus, we predict an interaction in which the effect of SES on self-selection into

accounting depends on whether or not there is a recession, i.e., conditions of resource scarcity.

Hypothesis 3: Selection into accounting among low SES individuals decreases in uncertain, as opposed to benign macroeconomic conditions. This effect is stronger in accounting than in non-accounting business fields and all non-accounting fields.

15

3. Tests of H1—Life History Strategies of College Attendees versus Non-Attendees

3.1. Data

Data for testing H1 are from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY).7 The NLSY is a survey of roughly 10,000 randomly-selected Americans born between 1957 and 1964.

It begins in 1979 and has been updated 24 times through 2012 to track participants’ ongoing labor

market activities and other significant life events. This dataset captures educational and career

activities, as well as self-reported lifestyle attributes and choices. It is an ideal dataset for testing

H1, because it allows linkage between indicators of early childhood SES, adolescent and adult

lifestyle attributes, and educational and career choices.

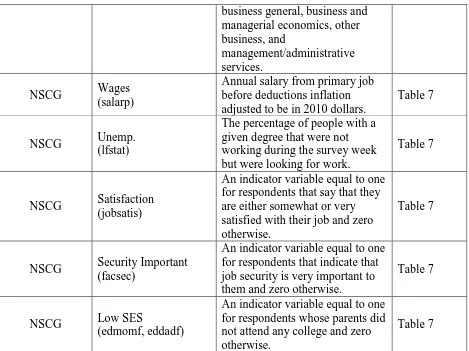

3.2. Variables

College attendee is our proxy for a person’s choice to pursue a college degree. We define

a college attendee as a respondent in the NLSY who had completed at least four years of college

by the age of 26.8 To proxy for low SES, we identified respondents whose parents had not attended any college when the survey began in 1979. Parental education level is a widely-accepted proxy

of SES, as it is positively associated with income and negatively associated with student loan debt

and full-time work as a source of tuition assistance (DeAngelo et al. 2011).

To find proxies for life history strategy speed, we search for variables that are both

available during the appropriate time in participants’ lives (late adolescence and early adulthood

when people also make career decisions) and relevant to our theory. We find five variables from

the NLSY that are available in relevant years and that theory suggests will be sensitive to the speed

7 See http://www.bls.gov/nls/nlsy79.htm and Appendix B for more information about the NLSY. We use the NLSY in tests of H1 but not in other tests, because the NLSY does not measure the degrees pursued by respondents attending college and graduating from college.

16

of a life history strategy. We use average age at first marriage, with older ages signifying a slower

strategy (Chisholm 1993, 9); average age at birth of first child, with older ages signifying a slower

strategy (Griskevicius et al. 2011b, Nettle 2010); average number of children, with fewer children

signifying a slower strategy (Nettle 2010); whether the respondent has smoked daily at any time in

their life, with not smoking signifying a slower strategy (Petridou et al. 1997; Hill and Chow 2002);

and the age at which the respondent began smoking daily, with older ages signifying a slower

strategy (Petridou et al. 1997; Hill and Chow 2002).

3.3. Results

We use a difference in difference analysis to test H1. Using the variables above, we

partition the sample into four groups: 1) college non-attendees who are low SES, 2) college

attendees who are low SES, 3) college non-attendees who are high SES, and 4) college attendees

who are high SES. H1 is supported by larger differences between college attendee and

non-attendee differences when socioeconomic status is low than when it is high, i.e., the difference

between groups (1) and (2) is greater than the difference between groups (3) and (4).

Table 1 shows that all five slower life history strategy proxies are consistent with low SES

college attendees being significantly more likely than low SES college non-attendees to have made

choices consistent with a slow life history strategy (all p ≤ 0.02).9 Further, there are five difference in differences in Table 1 to test whether the difference between college attendees and

non-attendees is greater for low SES than for high SES. The difference between college attendees and

college non-attendees is significantly greater for low SES respondents than for high SES

respondents on four of the five measures (p ≤ 0.09). The result for smoked daily is directionally

consistent with our predictions but not statistically significant (p = 0.13).

17

Our results support H1 that college attendees from low SES backgrounds have especially

slow life history strategies. Further, among college attendees, our results are consistent with low

SES individuals exhibiting even slower strategies than high SES individuals on average number of

children (p = 0.03) and smoked daily (0.07). Thus, the pool of low SES people minimally eligible

to select into accounting are predominately those with slow life history strategies. This point is

critical in examining determinants of entry into accounting, as we theorize that distinguishing

features of accounting likely make it appealing to people pursuing slower strategies.

4. Experimental Tests of H2 and H3 – SES and Self-Selection into Accounting

We test H2 and H3 using multiple methods due to the paucity of data on self-selection and

the complex array of factors that could influence this decision. To maximize the internal validity

of our inferences, we first test these hypotheses with an experiment using upper-division

accounting students. In particular, we use priming procedures to actively manipulate cues of

macroeconomic uncertainty (i.e., recession versus neutral) and randomly assign participants to

observe recession versus neutral primes. Because we cannot actively manipulate SES, the

experiment only allows us to make associational claims about H2. However, randomly assigning

participants to different primes does allow us to make strong causal inferences about H3,

specifically, the effects of the recession prime on career intentions within a given level of SES

(e.g., how do low SES individuals respond to recession, as opposed to neutral primes?).

4.1. Participants and Procedures

Experimental participants (n = 245) are business students recruited from accounting classes

at a large public university in the Southeast United States, of which 209 (85.3%) were accounting

majors. The sample comprises 51 (20.8%) freshmen and sophomores, 87 (35.5%) juniors, 47

18

a 600-word story that contained our priming manipulation (described below). To ensure that

participants attended to the prime and did not believe that the prime was related to their career

intention judgment, the instructions directed participants to assume that the prime was “like a

memory task” and that there would be questions about the story at the end of the study. After

reading the story, participants completed a series of questions about their career intentions,

answered manipulation and attention check questions, and answered questions about their

childhood and current SES. To avoid deception, we included memory questions about the story to

follow through on the statement in the materials that the story was like a memory task.

4.2. Variables

4.2.1. Recession prime

In the recession prime condition, participants read a story about economic hardships

confronted by recent college graduates. The story—titled “Tough Times Ahead: The New

Economics of the 21stCentury”—was formatted to look like a news article and was adopted from Griskevicius et al. (2011b and 2013). In brief, the story focused on economic hardships confronted

by recent college graduates, including skyrocketing student loan debt, intense labor market

competition, increasing food and energy costs, and diminishing funds for government social

support programs. In the control condition, the story (also adopted from Griskevicius et al. 2011b

and 2013) was designed to elicit similar levels of negative arousal. 10 The story focused on a person spending several hours looking for keys around their house. We could have used a neutral prime

that described good economic conditions, but that would have risked manipulating negative

arousal along with macroeconomic cues.

19

As manipulation checks, we asked participants in each condition to rate the extent to which

the story made them believe the world will become (1) more unsafe, (2) more unpredictable, and

(3) more uncertain. Participants’ responses in the recession condition were higher than those in the

control condition on all three measures (all p < 0.01), but did not differ on measures of negative

arousal such as anger, frustration, or stress that could influence the career intention judgment. This

indicates a successful manipulation that varied the uncertainty of the environment, but held

constant levels of negative arousal that could influence our measures. See Appendix A.

4.2.2. SES

To capture SES, we asked participants to report whether or not they are a first generation

college student. We classified participants as low SES if they reported having no parent(s) or

guardian(s) with a college degree and as high SES if they reported at least one parent or guardian

with a college degree.11

Self-Selection into Accounting

We measured our primary dependent variable on a 100-point scale that asked participants

to assess the likelihood that they intend to pursue a career in accounting. The instrument also asked

participants to rate the likelihood with which they intend to pursue careers in close substitute fields

such as finance, investment banking, or consulting. In addition, participants assessed the

importance of five characteristics of a job / career: job security, high earnings, likeable colleagues,

interesting work, and maximizing future opportunities.

20 4.3. Results

4.3.1. Tests of H2 and H3

H2 predicts that low SES individuals are more likely to select into accounting. H3 predicts

that uncertain macroeconomic conditions, of which recessions are a common contemporary

indicator, will decrease self-selection into accounting by people from poorer backgrounds. To test

this, we conduct a 2 (Prime: recession, control) X 2 (Childhood SES: low, high) Analysis of

Variance (ANOVA) with the assessed likelihood of pursuing a career in accounting as the

dependent measure. See Table 2 for ANOVA results and descriptive statistics.

Consistent with H2, in the neutral prime condition, intentions to select into accounting are

higher when SES is low, as opposed to high (78.00 versus 63.62, F1,241 = 8.02, p < 0.01). Further, the interaction predicted by H3 is significant (F1,241 = 8.42, p < 0.01). Specifically, observing the recession prime decreased the likelihood of pursuing a career in accounting when SES is low

(63.95 versus 78.00, F1,241 = 5.75, p = 0.02). Interestingly, though we had no hypothesis for how the prime would affect high SES individuals, Table 2, Panel C shows that observing the recession

prime marginally increased the likelihood of pursuing a career in accounting in this group (70.57

versus 63.63, F1,241 = 7.29, p = 0.10).12 Thus, H2 and H3 are supported, and the data are consistent with our hypothesized interaction being a causal effect.

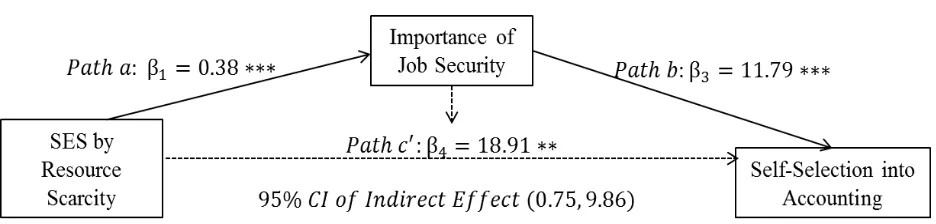

4.3.2. Supplemental Test of the Mediating Effect of Job Security

To provide further corroboration of the cognitive process that underlies our effects, we

examine participants’ ratings of the importance of job security to their career decision. Our theory

21

argues that H2 and H3 occur because low SES college students follow slow strategies in benign

conditions but adopt faster strategies in uncertain conditions. If our theory is valid, then SES and

recession jointly affect a person’s likelihood of self-selection into accounting because they jointly

affect the importance of job security to that person. That is, our interaction is likely to have an

indirect effect on self-selection, via differences in the importance of job security.

Following the recent statistics literature, we test the significance of the indirect effect using

a bootstrapping technique (Preacher and Hayes 2008; Hayes and Preacher 2013). Because our

independent variable is an interaction term, we follow the guidance of Hayes and Preacher (2013)

to create a multi-categorical independent variable using the linear weights for the interaction

term.13 We use 5000 bootstrap re-samples of the data to calculate bias-corrected confidence intervals for the total indirect effect. Significance is indicated by confidence intervals that do not

include zero. In our analysis, there is a significant indirect effect of life history strategy on

self-selection into accounting, which is mediated by the assessed importance of job security (lower CI

= 0.75, higher CI = 9.86). See Figure 1. Thus, our data support the conclusion that the SES by

recession prime interaction affects self-selection into accounting because it affects the importance

of job security.

5. Archival Tests of H2 and H3 – SES and Self-Selection into Accounting

We now turn to tests of H2 and H3 using large-sample archival evidence to provide comfort

about the generalizability of our findings.

22 5.1. Sample

We obtain data from the Higher Education Research Institute’s (HERI) Freshman Surveys,

which contain data collected from millions of incoming college freshmen annually since 1971

(UCLA 2013). The surveys describe how students choose which college to attend as well as their

demographics, high school academic and extracurricular activities, opinions on a wide array of

topics, values, and the field in which they intend to earn a degree. HERI data from 1971 to 1999

are available to all registered users of HERI’s website in an archive file. More recent data are

available for purchase contingent on approval from HERI. In this study, we use subsets of HERI

data from the archive as well as data purchased for 2000 and 2002.14 We conduct our main tests using subsets of years from 1971-2002 for which our variables are available.15 The sample size in our main tests is 125,125 accounting observations, 407,235 non-accounting business observations,

and 2,993,954 non-accounting observations.16

In addition, to test the robustness of H2 and to perform certain supplemental analyses

(described later), we also obtain a subset of the HERI database that collects responses both when

individuals were freshman and when they were seniors. This dataset is only available from 1994

– 1999, thus tests using the senior data have lower statistical power than tests using the freshman

dataset. Also, no recessions occurred during 1994 – 1999, thus we cannot use it to test H3.

14 The 2000 and 2002 samples differ somewhat from the earlier samples because HERI was unwilling to release the entire database to us. Rather, for 2000 and 2002 HERI provided us with all observations of students selecting any business field and a random sample of observations representing students selecting non-business fields.

15 See http://www.heri.ucla.edu/abtcirp.php and Appendix B for more information about HERI variables and data availability.

23 5.2. Variables

5.2.1. Self-selection into accounting

To test self-selection into accounting, we partition our sample into students planning to

major in accounting and those not planning to major in accounting. This is a reliable predictor of

selection into accounting jobs (Madsen 2015). We use two comparison groups to test our

hypothesis. We test self-selection into accounting against “non-accounting business” fields

(business administration, finance, international business, marketing, management, and other

business) and against “all non-accounting” fields (the set of all non-accounting fields).

5.2.2. SES

We manually search the HERI codebook and identify three measures of childhood SES

that are both available throughout the whole sample period and relevant indicators of low SES.

They are 1) whether or not the respondent indicated that cheap tuition was “very important” to

them when selecting a college, as prior research has shown that low SES students are particularly

sensitive to tuition costs (Heller 1997, 638-642); 2) whether or not the respondent is a first

generation college student, as first generation college students come from poorer families on

average (Terenzini et al. 1996, 8-9), and whether or not the respondent’s estimate of their parental

income is in the bottom third of the sample for that year, which is a direct measure of respondents’

perceptions about relative household income.17 For each of these measures, we create a dummy variable equal to 1 for values representing low SES and 0 otherwise.18 We then sum these three

24

dummy variables to create a low SES index. Higher values of the low SES index indicate lower

SES. Our main tests involve comparing values of the low SES index for students who have selected

accounting degrees against values for students selecting other degrees.

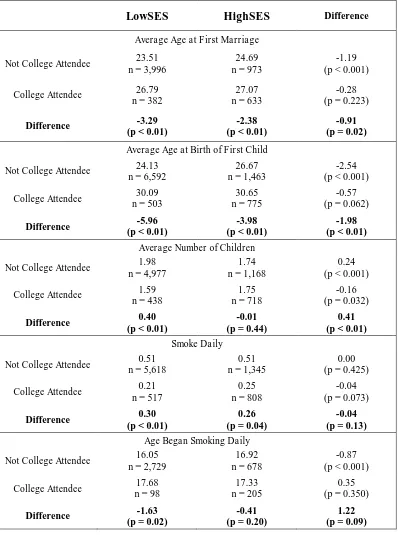

Table 3, Panel A sorts all fields in the HERI freshman database based on our low SES index

in recession and non-recession years, with higher values indicating higher representation of low

SES individuals. Accounting stands out relative to other fields and to business fields in particular,

ranking 11th overall out of 76 fields in low SES. These results suggest that accounting is by far the most appealing business field to low SES individuals, versus management (35th), business administration (39th), marketing (69th), and finance (70th). Table 3, Panel B shows that accounting has the 12th largest decline in the low SES index in recession years. All other business fields experience smaller declines in the low SES index during recession years, as no other business field

ranks higher than 38th in the magnitude of the decline (Finance). Indeed, accounting appears to occupy a unique niche among business fields and among most fields in general.19

5.2.3. Uncertain Economic Conditions

Our proxy for uncertain economic conditions is a year in which a recession occurred. We

partition the sample period into recession years and non-recession years. Recession is an indicator

for any year that includes at least one month classified by the National Bureau of Economic

Research as a recession month. Recession years during our sample period are 1973-1975,

1980-1982, and 1990-1991.

25 5.3. Results

5.3.1. Hypothesis 2 – Univariate Tests of the Effect of SES on self-selection into accounting

Table 4, Panel A presents univariate analyses. It provides mean values for each of our low

SES indicators, both separately and when aggregated, in accounting, other business fields, and all

non-accounting fields. H2predicts that a low SES background is positively associated with

self-selection into accounting. Consistent with H2, accounting students have higher values than

non-accounting students for each of our low SES indicators. These differences are even larger when

comparing accounting to other business fields. Table 4, Panel A also presents the univariate results

among college seniors. Because people from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to drop

out of college before they become seniors, all three low SES indicators are lower in the senior

dataset than in the freshman dataset. The senior dataset also has substantially smaller sample sizes

and lower statistical power. Notwithstanding these limitations that bias against our findings, H2 is

robust among college seniors. Thus, our univariate analyses support H2.

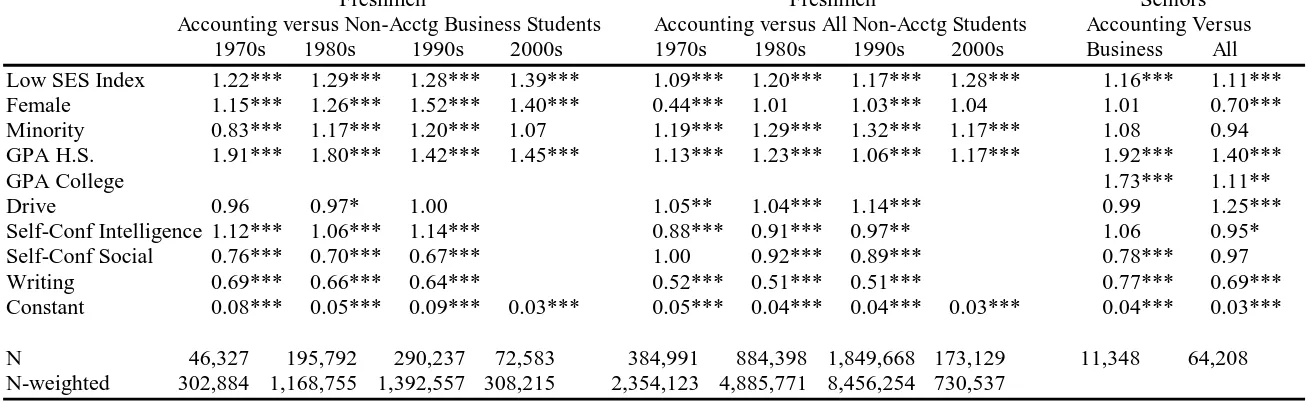

5.3.2. Hypothesis 2 – Multivariate Tests of the Effect of SES on self-selection into accounting

Table 4, Panel B presents results of a logit analysis that predicts the likelihood of selecting

into accounting based on SES, which we estimate separately during the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and

2000s (only the years 2000 and 2002 due to data limitations) to illustrate the effect’s robustness

over time. We estimate the following model:

Select Accounting (0 or 1) = α + β1*lowSES + β2*Female + β3*Minority + β4*GPA + β5*Drive + β6*Self-confidence intelligence + β7*Self-confidence social + β8*Writing + ε (1)

Our primary variable of interest is lowSES and we predict a positive effect for this variable,

i.e., an odds ratio greater than one. We report coefficients in the form of odds ratios, which are

26

the effects of a given variable. In brief, odds ratios represent the number of people in our sample

with a given attribute choosing accounting for every one person choosing a business degree (under

the heading “freshmen: accounting versus non-acctg business students”) or any other degree

(under the heading “freshmen: accounting versus all non-acctg students”). Table 4, Panel B also

shows similarly calculated results for college seniors (under the “seniors” heading).

To select control variables, we collected input from seven senior managers and partners in

public accounting firms about desired attributes that lead to success in an accounting career. We

presented each person with a list of 16 items from the HERI survey that we expected could be

related to success and asked each person to select the five that are most likely to lead to success in

accounting. We control for variables that were selected by a majority of respondents. Specifically,

we include GPA on a four-point scaleas a proxy for academic ability (high school GPA for college

freshmen and college GPA for college seniors), an indicator variable for above average

self-assessed drive as a proxy for motivation, indicator variables for above average self-assessed

intellectual and social self-confidence, and an indicator variable for above average self-assessed

writing ability as a proxy for writing skills. We also include indicator variables for Female and for

membership in a disadvantaged minority race or ethnicity, which we label Minority and includes

Black, Hispanic, and American Indian people. We include Female and Minority to provide insight

into the relation between our effect and the diversity of the accounting labor pool. See Appendix

B for details about the variables.20

The results in Table 4, Panel B support the idea that low childhood SESsignificantly and

positively predicts the likelihood of selecting into accounting in each of the sample periods. Thus,

27

multivariate analyses support H2. These analyses show that our effect is also robust to controlling

for race, gender, academic ability, self-confidence, motivation, and writing ability. The results also

indicate a few potentially problematic patterns for accounting. While GPA is positively associated

with accounting in every sample period and relative to both business and non-business fields,

individuals selecting accounting appear to possess lower social self-confidence and writing ability.

We explore these issues in Section 6.1 to examine whether or not the low SES effect may help

overcome some deficits in the entry-level accounting labor pool. Life history theory suggests this

is possible, as those adopting slower life history strategies tend to be highly capable. Because low

SES individuals have different life experiences than their high SES counterparts, they may also

possess high levels of different capabilities and thus improve the quality of the entry-level

accounting labor pool.21

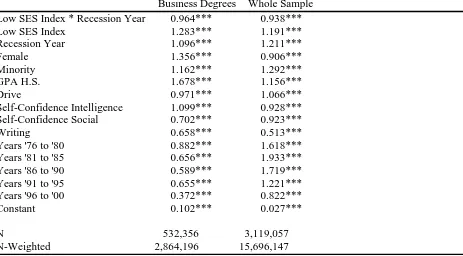

5.3.3. Hypothesis 3 – SES in recessions and non-recessions

The HERI data also permit us to provide large-sample analysis of H3, which predicts that

recessions decrease preferences for accounting when SES is low, and do so to a greater degree in

accounting than in other fields. Our univariate analysis of H3 is presented in Table 5, Panel A.

28

We conduct a difference in difference test that compares the decline in the low SES index in

recession, as opposed to non-recession years in accounting to the decline in other fields. The results

show that low SES representation on average drops in accounting, in other business fields, and in

all other fields during recession years. This is consistent with recessions more negatively affecting

rates of college attendance among people with fewer economic resources. However, the decline in

low SES representation is larger in accounting than in other business fields (p < 0.01) and in the

set of all other fields (p < 0.01). Thus, the results support H3.22

We report multivariate analysis of H3 in Table 5, Panel B, which is based on the model:

Select Accounting (0 or 1) = α + β1*lowSES + β2*lowSES*Recession + β3*Recession+ β4*Female + β5*Minority + β6*GPA + β7*Drive + β8*Self-confidence intelligence + β9*Self-confidence social + β10*Writing + time period dummies + ε (2)

Our primary variable of interest is the lowSES*Recession interaction. We expect this

interaction effect to be negative, i.e., an odds ratio lower than 1. The control variable definitions

are the same as in equation (1). Because there are time trends that affect our variables of interest,

including fewer first generation college students and increasing popularity of business fields in

general, we also include dummy variables for each five-year time period in our sample to ensure

that our analyses are not confounded by time effects. The reference time period to interpret each

time period effect is 1971 – 1975, i.e., each time period effect tests the interest in accounting in

that time period relative to interest in 1971 – 1975.23

22 Ideally, we would also be able to explicitly identify the fields chosen by people who might otherwise select into accounting. However, we are unable to capture this data, even with our dataset of seniors that allows us to observe switches between fields. First, the senior dataset only includes years in which there were no recessions, thus we could not observe differences in substitutes between recession and non-recession years. Second, this dataset only captures alternatives to accounting for those who actually remained in college, and earning a degree is an inherently slower strategy than dropping out. Thus, the data will understate the life history speed of alternatives, and this understatement is likely stronger among low SES individuals, who are more likely to drop out of college.

23 We use time period dummies instead of year fixed effects because Recession is defined at the year level. In each model, the odds ratios for selecting accounting decrease over time. For example, for every person selecting

29

As predicted, the results show a negative interaction effect in which low SES interest in

accounting is lower in recession years, and this decrease is greater in accounting than it is in

business fields and in the set of all fields. This interaction is striking because, in both columns of

Table 5 Panel B, Recession is associated with higher interest in accounting. That is, interest in

accounting among low SES individuals is lower during times when overall interest in accounting

is higher. We argue that this is due to people from poorer backgrounds adopting faster trajectories

in their life history strategies when they observe cues of economic uncertainty. Importantly, if the

recession interaction effect simply reflected fewer low SES individuals in college during

recessions due to lower application rates or higher dropout rates, then lower SES representation in

accounting would not differ from that of other fields. Thus, our multivariate analyses support H3.

In sum, these archival analyses provide evidence both that our theorized relations

generalize in a large-sample dataset of millions of real choices and that the effects are robust over

time. Low SES individuals disproportionately prefer accounting because it is consistent with a

slow life history strategy. However, recessions affect patterns of selection into accounting

differently than other fields, as the preference for accounting by low SES individuals

disproportionately weakens.

6. Supplemental Analyses

In this section, we explore the potential implications of our findings for the profession and

for low SES individuals. Specifically, our supplemental analyses first examine implications for the

quality of human capital entering accounting, i.e., under what conditions do our theorized effects

have benefits for accounting? We then examine job outcomes of those who select into accounting

and of low SES individuals who select accounting, as opposed to other fields. This provides some

30

evidence as to whether or not accounting is a slow life history choice relative to common

alternatives, and whether the benefits of a slow life history strategy materialize similarly for low

SES individuals and high SES individuals. If our theory suggests that accounting attracts entrants

because of its security, then this analysis helps identify if accounting delivers this security.

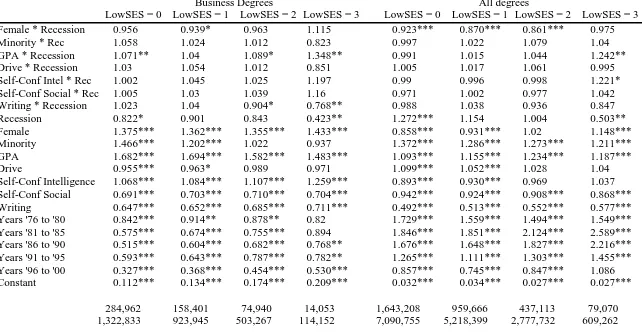

6.1. Implications for the Quality and Diversity of Human Capital Entering Accounting

6.1.1. Low SES, Self-Selection, and Human Capital

We first examine implications of our effects for the quality of human capital in the

entry-level accounting labor pool. To do so, we analyze equation (1) at each possible entry-level of lowSES to

examine if any of the desirable human capital attributes vary with low SES.24 Recall that the

lowSES values indicate how many of three low SES indicators a person possesses, thus SES is

lower as the number of lowSES indicators increases. The first noteworthy finding is that the data

are consistent with the low SES effect increasing gender diversity in the accounting labor pool. As

shown in Table 6 at the lowest SES level (lowSES = 3), 1.455 women select accounting for every

woman who selects another business field and 1.149 women select accounting for every woman

who selects another non-business field. By contrast, women from wealthier backgrounds tend to

select accounting at disproportionately low rates.

In addition, recall that the results in Table 4 Panel B identified potential deficits in the

accounting labor pool. Our expert panel identified writing skills and self-confidence as critical to

distinguishing successful performers in accounting, but the results show that accounting entrants

lag in these categories. However, Table 6 suggests individuals selecting accounting possess higher

levels of these attributes as lowSES increases, relative to business fields and to other fields. In

31

brief, the results indicate that the quality of the entry-level accounting labor pool benefits from the

low SES effect.25

6.1.2. Do Recessions Undermine Human Capital Benefits for Accounting?

If the low SES effect channels quality talent into accounting, then H3 could naturally

decrease representation of this talent and have negative implications for accounting. To assess

implications of H3, we analyze a version of equation (2) which has been modified to include

interactions of the Recession indicator variable with our control variables at each possible level of

lowSES. As shown in Table 6 Panel B, two noteworthy effects emerge from this analysis. First,

the odds ratios for the Female*Recession interaction are less than one across many levels of

lowSES, particularly when the comparison group is all non-accounting degrees.

Thus, the recession effect disproportionately reduces the representation of females from

poorer backgrounds. That is, the low SES effect appears to increase gender diversity in accounting

but uncertain economic conditions reverse this positive effect. This may suggest that bad economic times undermine accounting’s potential to act as a secure path to business careers for women from

poor backgrounds. That is, a gender gap may exist in the potential for accounting to elevate those

from poorer backgrounds. Future research into this possibility is warranted.

Second, there is a significant GPA*Recession interaction with an odds ratio greater than

one for most levels of SES. This appears to benefit accounting on the surface, as academic ability

increases relative to other business fields and to all other fields. We rerun equation (2) at each level

of reported GPA in the HERI data in order to more deeply examine whether this effect is likely to

32

benefit accounting. In Table 6 Panel C, the results are not definitive, as the lowSES*Recession

interaction effect is negative for students averaging a B or B+, but positive for students averaging

an A-. It is not significant at any other GPA levels. That is, recessions appear to negatively affect

selection into accounting among low SES individuals with above average, though not exceptional

ability.

This finding may reflect subtle differences in how capability can affect a person’s life

history strategy. Those with above average ability may fear being squeezed out by high ability

individuals, and thus lack confidence that they will be able to experience deferred rewards. As a

result, low SES individuals in this group may revert towards a faster life history strategy when

they observe resource scarcity cues, in order to “get what they can when they can.”

6.2. Career Outcomes - Evidence that Accounting is Part of a Slow Life History Strategy

The remainder of our analyses focus on providing evidence that accounting is, in fact, a

slow life history strategy relative to potential substitutes. Further, we examine whether low SES

individuals selecting accounting realize the benefits of a slow life history strategy—that is, does

accounting deliver on expectations? To address this question, we compare job outcomes of

accounting degree holders to three comparison groups: (1) finance degree holders, (2) other

business degree holders, and (3) non-business degree holders. For brevity, we provide details on

our sample and methodology in Appendix C, and summarize our findings here.

As indicators of a slow life history strategy, we examine whether accounting delivers

relatively high mean wages with low wage variance, low unemployment, and high job security.

Table 7 reports career outcome results for those whose highest degree is a Bachelor’s degree in

33

depicting the full sample and the right columns depicting the low SES sample only. Our low SES

proxy is first generation college students.

The data support our central theoretical assumption that accounting reflects a relatively

slow life history strategy. Accounting has a relatively high mean salary with a relatively low

standard deviation, which suggests that accounting degrees lead to relatively high “wage floors.”

Moreover, accounting degree holders have unemployment that is lower than in finance, other

business fields, and non-business fields. In general, our results indicate that, accounting careers on

average deliver the attributes of a slow life history strategy. The data are roughly consistent in the

full sample of accounting degree holders and the sample of only low SES individuals, suggesting

that low SES accountants do not experience worse labor market outcomes.

This contrasts with a striking pattern in finance, which is a common alternative to

accounting. The data suggest that Master’s degrees in finance deliver substantial rewards, but not

for low SES individuals. Low SES Master’s degree holders compare unfavorably to other finance

Master’s degree holders in mean earnings ($66,989 versus $87,826) and unemployment (9.88%

versus 4.52%). By contrast, low SES Master’s degree holders in accounting are comparable to other accounting Master’s degree holders in terms of wages ($65,866 versus $68,552) and

unemployment (0.77% versus 0.93%).

A plausible explanation is that maximizing the benefits of a Master’s degree in finance

requires the type of social capital (i.e., relationships with well-connected people) that low SES

individuals possess at lower rates. This is consistent with research by Rivera (2015) that hiring

practices of financial institutions systematically favor those from wealthier backgrounds. By

contrast, social capital may not be as important in realizing the benefits of an accounting degree.

34

accounting’s faster, most common alternative. If a low SES individual wants to compete on an

equal playing field in a business career, then accounting is a relatively safe and effective choice.

7. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

The accounting profession is dependent on the supply of entry-level human capital into the

labor market, but little is known about the determinants of self-selection into accounting. This

study uses multiple methods and datasets to examine why people self-select into accounting,

focusing on how self-selection depends on SES and the economic conditions at the time of

selection. We explain our findings through the lens of life history strategies, drawn from

evolutionary biology and psychology.

We find that low SES college attendees, i.e., the pool of minimally-qualified individuals to

enter accounting, follow predominately slow life history strategies. That is, they make choices

consistent with long-term security. Consequently, our experimental and archival evidence shows

that low SES individuals disproportionately self-select into accounting relative to non-accounting

business fields and all non-accounting fields. However, low SES individuals are less likely to

select accounting in recession, as opposed to non-recession years, and this effect is stronger in

accounting relative to non-accounting business fields and all non-accounting fields. Our evidence

suggests that this joint effect on self-selection is driven by the importance of job security. Further,

supplemental analyses show that accounting careers deliver the benefits of slow life history

strategies to low SES individuals, in the form of high mean wages, low wage variation, and low

unemployment. In sum, our study sheds light on part of accounting’s unique position in the job

market, specifically, as a secure path for low SES individuals to enter professional fields.

Accounting’s potential role as a socioeconomic “ladder” is important for labor market

35

possibly unintended discrimination against low SES individuals in professional fields such as law

and consulting (Rivera 2015), even by firms with good records of achieving racial and gender

diversity. For social welfare, identifying the life history attributes of different professions and

occupations can help identify hidden barriers to entry against low SES individuals. Examining

“slow” fields may illuminate paths to upward mobility by low SES individuals, and examining

“fast” fields (e.g., finance) may identify obstacles limiting the success of low SES individuals.

For the accounting profession, understanding the vector of attributes that lead people to

select accounting can help business schools, firms, and the broader profession improve the

recruiting and retention of talented low SES individuals. Our study is a first step to shed light both

on what appeals to low SES individuals, and conditions under which accounting is less likely to

appeal to them. For example, at a practical level, accounting firms incur substantial costs to

personalize their recruiting mechanisms for students, and understanding that SES influences the

appeal of accounting degrees and jobs is potentially beneficial. The effects of SES may help

suggest first steps for accounting firms to tailor recruiting and retention mechanisms, job design,

and compensation packages to most effectively match the choice of accounting to life history

strategies. For instance, public accounting firms offer a variety of jobs such as auditing versus

advisory that vary in their degree of consistency with slower or faster life history strategies. If an

individual is likely to adopt a temporarily faster trajectory, then an employer could consider

adjusting that person’s task mix to include more work consistent with this strategy (e.g., advisory

work). Our findings suggest that the effectiveness of recruiting for different types of positions is

likely to change based upon a candidate’s background and current macroeconomic conditions.

This study opens numerous avenues for future research. A natural extension of this research