THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA

COUNTRY SERVICE FRAMEWORK

2003-2004

This document has not been officially edited November 2002

NLMセMLN@

UNIDO

セセ@ UNITED NATIONS INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATION

Table of Contents

Chapter Page

Abbreviations . . . ... . . ii

Executive Summary... 1n I. COUNTRY CONTEXT . . . .. . . .. . .. . . .. . . .. . . .. ... 1

A. Overview of the Economy... 1

B. Trends in Industrial Development .. .. . .. . . .. . . .. . . .. .. . . .. 3

C. Principal Industrial Development Issues and Challenges . . . ... 6

D. Country Strategy, Development Objectives and Priorities... 9

E. External Development Assistance and Donors Priorities . . . .... . . ... 11

II. THE CURRENT UNIDO PROGRAMME IN INDONESIA . . . ... . . ... 12

A. Overview . . . .. . .. . . .. . . .. . ... . . .. . .. .. . .. . . .. .. . . .. . . ... 12

B. Lessons Learned .. . .. . . .. . . .. . . .. . . .. ... .. .. . . .. .. . . .. .. . . .. . .. .... 12

ill. THE UNIDO COUNTRY SERVICE FRAMEWORK . .. .. . .. . .. . . ... . . .. . . 14

A. Background . . . 14

B. Duration of the CSF ... ... ... ... ... ... .... 14

C. Strategic Themes/Focus of the UNIDO Country Service Framework... 14

D. Main Programmes Proposed... 18

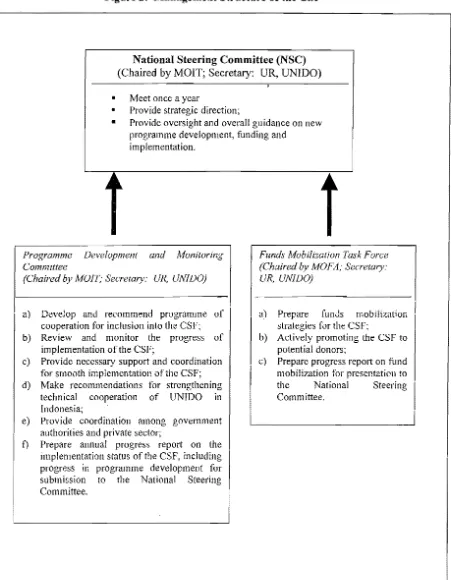

IV. MANAGEMENT OF THE CSF... .. . . ... .. 27

A. Implementation Plan and Modalities . . . 27

B. Development and Addition of New Programmes/Activities... 30

C. Review Mechanism and Performance Indicators... 30

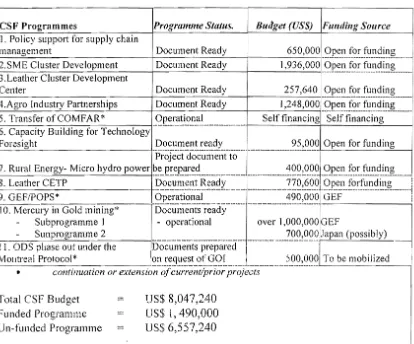

D. Resources Mobilization... 30

Abbreviations

AFTA APEC ASEAN BAPENAS BMZ CAD CAM CATD CETP CNC COMFAR CSF FDI FMTF FSC GDP GEF GTZ IRDL.A.I ITPO .TICA MOIT MOFA MVA NGO NSC ODA ODS OECF PDMC POPs R&D SMEs SWOT TF UN UNDP UNICEF UNIDO UR V/HO WTOASEAN Free Trade Agreement Asian Pacific Economic Cooperation Association of Southeast Asian Nations

National Development Planning Agency, Indonesia

Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, Germany

Computer Aided Design

Computer Aided Manufacturing

Center for Appropriate Technology Development Common Effluent Treatment Plant

Computer Numerical Control

Computer Model for Feasibility Analysis and Reporting Country Service Framework

Foreign Direct Investment Funds Mobilization Task Force Footwear and Shoes Center Gross Domestic Products Global Environment Facilities

German Corporation for Technical Cooperation

Institute for Research and Development of Leather and Allied Industries

Investment and Technology Promotion Office Japan International Cooperation Agency Ministry oflndustry and Trade

Ministry of Foreign Affairs Manufacturing Value Added Non-Governmental Organization National Steering Committee Official Development Assistance Ozone Depleting Substances

Overseas Economic Cooperation Fund

Programme Deveiopment and Monitoring Committee Persistent Organic Pollutants

Research and Development

Small- and Medium-Scale Enterprises

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats Analysis Tech1iology Foresight

United Nations

United Nations Development Programme United Nations Children's Fund

United Nations Industrial Development Organization UNJDO Representative

Executive Summary

Indonesia stands at a crossroads in the current phase of its history. It faces the simultaneous challenge of overcoming the numerous effects of a debilitating economic reversal, creating a new democratic and accountable framework for government, preventing territorial fragmentation and diffusing ethnic, religious or sectarian conflict. Meeting these challenges poses a formidable task. Whether Indonesia will manage to chart a course through the combination of difficult hurdles depends on the adeptness of the newly empowered political elite, the public credibility of democratic politics, the resilience of her institutions, her internal social cohesion and on the solidarity and support of the international community.

Since the mi<l 1980s, Indonesia saw a remarkably successful export oriented growth undertaken by private domestic capital and, to an extent, by foreign investors. In this period, the country's accelerated economic development and structural transformation was assisted by the 1985 currency readjustments under the Plaza Accord. With the strengthening of the Japa.11ese yen and rising manufacturing costs, Japanese, South Korean and Taiwanese firms sought lower cost manufacturing platforms in the open economies offered by Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. The restructuring occmTed especially in such labour intensive export oriented sectors as textiles, garments, footwear and assembly of electronics products. These gains were severely undermined by the consequences of the East Asian crisis of 1997.

Between 1985 and 1996, MV A grew between 9 and 12 per cent per annum. It grew by 5 .3 per cent in 1997 and contracted by 11.3 per cent in 1998, the year when the fullest effect of the crisis manifested itself. Recovery has been erratic in the last three years with manufacturing output growing 3.8 per cent in 1999, 6.2 per cent in 2000 and 4 per cent in 2001.

Despite the industrial suGcesses, Indonesia has not graduated up the manufacturing value chain over the last fifteen years. In addition, assembly based large-scale industries now face stiff competition in the ii1ternational investment and product markets, creating a threat of industrial stagnation or even substantial de-industrialization.

The government has recently announced industrial revitalization programme as a national priority programme, requiring the commitment of all actors--the private sector, financial institutions, the support institutions and all concerned branches of Government-to achieve its production, export and employment targets for the industrial sector. This policy statement enunciates legislative, financial, investment support, trade promotion and infrastructure improvement measures to support the realization of targets to be achieved by the year 2004. In addition a great deal of emphasis is placed on support to Small and Medium Scale Enterprises, which have assumed ever more policy importance in the light of cmTent economic realities.

from the provision of food aid, supporting the social safety net, to supporting more effective commercial law enforcement, development of civil society, supporting the consolidation of democracy, the implementation of the law on decentralization, conflict resolution, relief for internally displaced persons and relief and rehabilitation in conflict zones.

Indonesia's development policies and plans establish, three clear priorities for the industrial development agenda, i.e.,:

• The need to suppo1i enhanced national industrial competitiveness at a time that Indonesia faces competitive pressures from within the Asian region and elsewhere;

• To need to address the longer-term industrial development agenda in relation to its impact on poverty alleviation, whether through the development of small scale industry or through the development of agro industries or by supporting community recovery from the crisis;

• To need to pursue environmentally sustainable industrial development, as a response to regional or global concerns, or as a response to local problems.

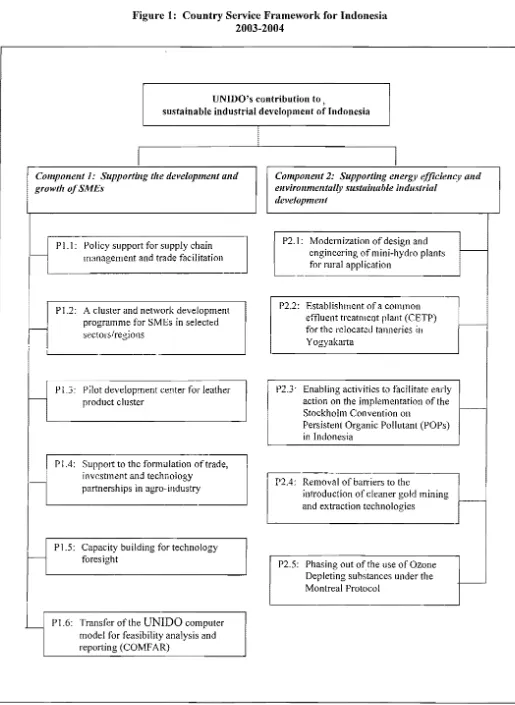

These clearly fit into UNIDO's global priorities of improving industrial efficiency, enhancing employment and safeguarding the environment. Based on these considerations, the Country Service Framework defines two components under which UNIDO services could be offered to Indonesia (see Figure 1 ):

Component 1: Supporting the Development and Growth of SMEs: Despite the

preponderance of the number of SMEs, the sector is caught in a low-productivity equilibrium. While SMEs do account for a sizeable proportion of manufacturing establishments, their contribution to manufacturing has been far mote modest than their physical numbers would imply. They have made minimal contribution to growth in output, increase in productivity or the diversification of products and markets. Most SMEs in manufacturing are food processing and crafts based enterprises. or engage in the simplest levels of mechanized production. They are heavily reliant on trading or distribution intermediaries for product development, marketing, raw materials, intermediate inputs and working capital.

developed according to international standards while enabling Banks to evaluate the creditworthiness of those studies according to the same standards and methodologies. In this way the Organization will supplement domestic efforts by providing investment, technological and business support services in this sector.

Component 2: Supporting Energy Efflcie11.cy and Environmentally Sustainable Industrial Development: The rapid pace of economic growth and recent economic

turbulence pose a significant threat to the Indonesia's abundant environmental resoµrces. While inter-sector comparisons are difficult, the large-scale manufacturing industry is probably not the greatest cause of environmental stress, as the capital stock of such industry is of relatively recent vintage, with environmental safeguards built into the engineering design of machines and equipment. Also, large-scale manufacturing is subject to a fair degree of supervision by government for compliance with national environmental performance standards. Larger scale export oriented industries are also subject to environmental compliance standards set by foreign principles, buyers and customers. The present situation may, however, deteriorate in the future, as government supervision may become weaker and as the manufacturing sector faces increased competitive pressure.

The environmental problems confronting the country are large and complex. In response to these challenges, UNIDO proposes a three-pronged approach under this component. First, the Organization proposes to undertake pilot projects for alternative energy or environmentally efficient energy technologies; second it proposes to undertake demonstration projects to reduce em1ss1ons and pollutants in environmentally sensitive industries such as the tanning industry; and third it will support technological transformation in certain sectors where Indonesia is obligated to protect the Global Commons under various international environmental conventions.

In conclusion, it needs to be noted that the size and diversity of Indonesia's industrial sector demand a degree of selectivity in determining issues that need to be addressed by UNIDO. The Organization's limited human and financial resources in relation to those of the several larger development partners in Indonesia, dictate that UNIDO's support has to be strategic and/or of a pilot nature, with the intent of developing and demonstrating innovative approaches to problems addressed.

Also, the preponderant influence of the private sector in Indonesian industry make it a central actor in our activities, whether as a beneficiary of UNIDO efforts or as a development partner along with the Government Ministries and Agencies. Over the years, in Indonesia and internationally, UNIDO has been able to network with important private sector players and NGOs, and these networks are a source of contacts, capabilities and knowledge that the Organization can bring to bear on the development issues addressed in Indonesia.

Finally, given the decentralization of the fiscal, administrative and developmental responsibilities of government, UNIDO interventions should solicit the greatest possible involvement of local governments and development partners at the provincial level.

Figure 1: Country Service Framework for Indonesia 2003-2004

UNIDO's contribution to,

sustainable industrial development of Indonesia

I

I

Component I: Supportillg t!te developmellt ttml Component 2: Supporting energy efficiency and

growt!t of SMEs

Pl.I: Policy support for supply chain

- management and trade facilitation

·-I

Pl.2: A cluster and network developmentI

programme for SMEs in selected

n

sectors/regions. i

Pl.3: Pilot development center for leather

- product cluster

I

Pl .4: Support to the formulation of trade,I

investment and technoiogy"

11

partnerships m agro-mdus:::JPl.5: Capacity building for technology

- foresight

Pl.6: Transfer of the UNIDO computer

-model for feasibility analysis and reporting (COMFAR)

environmentally sustaimtble industrial tlevelopment

P2.l: Modernization of design and engineering of mini-hydro plants for rural application

P2.2: Establishment ofa common

!

effluent treatment plant (CETP) for the relocatcJ tanneries inl

YogyakartaP2.3· Enabling activities to facilitate early action on the implementation of the Stockholm Convention on

Persistent Organic Pollutant (POPs) in Indonesia

! P2.4: Removal of barriers to the セ@ introduction of cleaner gold mining and extraction technologies

P2.5: Phasing out of the use of Ozone Depleting substances under the Montreal Protocol

[image:7.612.52.567.61.766.2]

-CHAPTER I:

COUNTRY CONTEXT

A. OVERVIEW OF THE ECONOMY

With a population of 210 million, Indonesia is the world's fourth most populous nation. Straddling the equator, it is also the world's largest archipelagic state, containing more than 13,000 islands spread over a distance of 5,000 kilometers from west to east. Indonesia has a wide range of natural resources oil, natural gas, coal, gold, silver, copper, tin and several other minerals, as well as timber and spices. The rich volcanic soils in some of the islands, particularly Java, enable the country to be largely self sufficient in rice, the national staple crop, despite the fact that only l0% of the land is suitable for agriculture. The country possesses a large plantation economy and is a major supplier of crude palm oil and rubber. It is also an exp011er of coffee and cocoa. With extensive and カ。イゥセ、@ coastal zones and the second largest tracts of primary tropical forest (after Brazil), Indonesia is a major repository of tropical terrestrial and marine biodiversity. Its 7.9 minion square kilometers of sea area make it the world's sixth largest producer of fish and the seventh largest exporter. The rich cultural heritage and natural beauty of the islands of the archipelago makes Indonesia a major international tourist destination.

Population and economic assets are unequally distributed. Only some 3,000 islands are populated. Two islands Java and Sumatra-- are home to nearly 80 per cent of the population. Java is home to over 120 million people living in an area equivalent to New York State. Three islands - Sumatra, Kalimantan and Irian Jaya - account for about half of the natural resources and plantations. Java is the location of 80 per cent of Indonesia's manufacturing sector and it generates 55 per cent of the GDP. Presently, about 29 per cent of the population is urban. This may rise to over 50 per cent by 2050, when the total population could exceed 250 million. Were this projection to be realized, Greater Jakarta would become one of the vwrld's mega-cities.

Indonesia suffered weak economic performance in the first 25 years after independence, Over the period J 982-97, the Indonesia economy undenvent a change in policy, characterized by openness to trade and investment; high domestic savings rates; prudent macroeconomic management; and sustained public investment in health, education, family planning and physical infrastructure. A remarkably successful development effort resulted in the economy growing by 7-8% annually, over the period 1985-96. GDP attained a levei of over US$200 billion in 1996.

crawling peg of the rupiah, its free convertibility, open capital markets and a favorable spread between US Dollar borrowing interest rates and rupiah rates of return on investment or lending, enabled domestic as well as foreign banks to rapidly expand internal and external lending to Indonesian companies, in order to create productive assets at a rate that has rarely been witnessed. On its part, the government managed its budgets prudently, balancing domestic deficits with a carefully serviced public sector foreign borrowing of about US$ 5 billion per year.

The story of Indonesia's crnTent political, social and economic development is inextricably linked to the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98. As is well known, the Asian financial crisis caused a collapse in investor confidence, starting in Thailand, and then spreading to other economies of the East Asian region. This collapse resulted in the flight, within a period of a few months, of an estimated US$ l 6 billion worth of foreign as well as domestic portfolio investments and other placements on the Indonesian capital markets. The government chose not to contest the market and to maintain its foreign currency reserves of some $17 billion. As a result, the Rupiah devalued to one sixth of its value between November 1997 and July 1998. The currency devaluation rendered much of Indonesia's large corporate debt as unserviceable, due to un-hedged US Dollar borrowing by Indonesian firms who operated mainly on rupiah denominated revenues. The non-serviceability of corporate debt also caused a near collapse of the domestic banking system that had either held corporate debt as a major asset, or had borrowed dollars offshore for domestic on-lending. Furthermore, it bankrupted the heavily leveraged construction industry, and generated widespread corporate insolvency. A further complicating factor lay in the Indonesian corporate structure, since interlocking asset holdings by conglomerates could not isolate those firms that were financially healthy from the liquidity squeeze caused by the de facto bankruptcies of their parent companies. Together, these developments caused a dramatic reduction in output and a sudden increase in unemployment. A powerful side effect of the currency devaluation was the inflation unleashed in an economy that is highly dependent on imports of investment as well as consumption goods.

Some indicators for 1998 bear testimony to the extent of the collapse. GDP contracted by 13%, inflation reached 77.8% and 1.5 million entered the ranks of the unemployed. The adversities of increased unemployment were, however, somewhat ameliorated by the absorption of displaced labour into agricultural and informal sector activity. In addition to the increased stock of unemployed created as an immediate legacy of the crisis, subsequent economic stagnation has increased the pressures of poverty, since 2.5 million Indonesians currently enter the labour force each year, and new employment opportunities remain scarce. Inflation and economic stagnation has caused the incidence of absolute poverty, which was estimated at 16% of the population in 1996, to increase to 25%, and recent World Bank estimates suggest that an additional 25% of Indonesia's people now face the threat of descending imo poverty. In piain terms, over 50 million Indonesians now suffer poverty and another 50 million face the threat of poverty.

Weak growth, such as that witnessed over the past three years, obviously prolongs the period over which past welfare levels can be regained. As a result of currency devaluation and the contraction brought on by the crisis, nominal GDP in 2001 1s about US$145 billion.

The government has had to bear the financial burden of the rescue of the banking system, with the result that Indonesia's current external debt is US$ 140 billion, of which roughly US$70 billion is external public debt. In addition, the government has incurred domestic debt of about Rp. 650 trillion (approximately US$ 65 billion at current exchange rates). Public debt, equivalent to 90 per cent of annual GDP, is amongst the heaviest debt burdens in the world, and its magnitude is due largely to attempts to rescue a faltering domestic banking sector. The IMF estimates that debt servicing will absorb one-third of government expenditure in 2000, and one quarter in 2001 and 2002. Consequently, over the next three or four years there will be marginal public development expenditure.

The economic and political upheavals of 1998, triggered by the cns1s, saw the dismantling of the hitherto prevailing model of governance-a model that entailed public acceptance of government authority in return for rapid economic growth. As a consequence, the country embarked on a course of democratization after 32 years of absolutist rule. The transition has been turbulent, as a new balance between different political stakeholders as well as a greater accountability of government is sought.

In 2001, in order to meet aspirations in various provinces of the country, the government adopted a wide-ranging decentralization programme, devolving authority to districts and provinces as regards fiscal expenditures and decision-making power on developmental priorities. Many local administrations, however, are ill prepared to effectively defray these responsibilities and, in some instances, business' suspicion of local-level conuption prevents the realization of local development plans and business initiative.

In summary, Indonesia stands at a crossroads. It faces the simultaneous challenge of overcoming the numerous effects of a debilitating economic reversal, creating a new democratic and accountable framework for government, preventing te1Titorial fragmentation and diffusing ethnic, religious or sectarian conflict. Meeting each of these challenges poses a significant task. Taken together, the challenges are formidable. Whether Indonesia will manage to chart a course through the combination of difficult hurdles depends on the adeptness of the newly empowered political ,elite, the public credibility of democratic politics, the resilience of her institutions, her internal social cohesion and on the solidarity and support of the international commw1ity.

B. TRENDS IN INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT

In the three decades following independence, industrial development was gradual, relying heavily on tariff protection, and consisting of the transformation of agricultural commodities and natural resources. Also, some assembly types of industrial operations were undertaken to serve the domestic market. Most industries inherited from the Dutch were taken over by the state and are still owned by the public sector.

Since the mid 1970s, Indonesia pursued a sustained policy of industrialization, in order to reduce the country's dependence on agriculture, as well as exports of oil and gas and primary commodities. Initially, this effort was manifested in tem1s of import substituting industrialization and there was substantial investment in public sector owned heavy industry, utilizing the revenues gained from the oil price adjustments of

1973.

By the mid 1980s, this model gave way to remarkably successful export oriented manufacturing undertaken by private domestic capital and, to an extent, by foreign investors. This investment driven and export oriented model of development was considered a textbook case in what was termed the East Asian Miracle. In this period, the country's accelerated economic development and structural transformation was assisted by the 1985 currency readjustments under the Plaza Accord. With the strengthening of the Japanese yen and rising manufacturing costs in Japan, Korea and Taiwan, the regional restructuring of manufacturing occurred at a dramatic rate as Japanese, South Korean and Taiwanese firms sought lower cost manufacturing platforms in the open economies offered by Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. The restructuring occurred especially in such labour intensive export oriented sectors as textiles, garments, footwear and assembly of electronics products.

Between 1985 and 1996, MV A grew between 9 and 12 per cent per annum. It grew by 5.3 per cent in 1997 and contracted by 11.3 per cent in 1998, the year when the fullest effect of the crisis manifested itself. Recovery has been erratic in the last tlu·ee years with manufacturing output growing 3 .8 per cent in 1999, 6.2 per cent in 2000 and 4 per cent in 2001.

Total exports reached about 33% of GDP and manufactured exports reached more than 50% of total exports. Manufactured exports grew by an annual average of 33 per cent per annum between 1985 and 1993. But this growth slowed down to an annual average rate of 10 per cent per annum between 1994 and 1997. This category of exports did not grow in 1998 and grew by 3 per cent n 1 999. However manufactured exports increased by 31 per cent in 2000, and then declined by 10 per cent in 2001 as a result of the burst of the information technology/electronics boom in the US. The share of manufacturing in GDP reached 26% by the year 2000.

Inflows of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), which were US$310 million in 1982. increased to about US$1.5 billion per annum by the early nineties, reaching their highest level of US$ 6 billion in 19961• There was a net outflow (FDI inflows minus

repatriated profits and other business fees) of US$400 million in 1998, after the East Asian Crisis. Those net outflows increased to US$2. 7 billion in 1999 and US$4.1 billion in 2000.

1

In addition to FDI, the inflow of international portfolio investment accelerated dramatically. From negative flows in prior years, portfolio investment inflows suddenly jumped to US$1.8 billion in 1993, and reached a record high of US$5 billion in 1996. Massive outflows of portfolio investment were recorded in 1998 and subsequent years. Outflows of portfolio capital amounted to US$13 .5 billion in 1998, US$7.2 billion in 1999 and US$4.4 billion in 2000.

Despite all the importance assigned to FDI in conventional wisdom, it may be borne in mind that it accounted for only about 6% of gross fixed capital formation in Indonesia over the period 1987-97. Most of investment in the country came out of domestic savings, which averaged about 29% of GDP. However, in liberalized capital markets, domestic investment knows no nationality. It is as much subject to market sentiment as is foreign investment. Thus, all investment, whether Indonesian or foreign, evaluates Indonesian investment prospects in relation to competitor countries, and flows to those countries that present optimum risk-reward opp011unities Presently, domestic investment is stalled due to political uncertainty, a largely non-performing domestic banking sector and corporate indebtedness to domestic and international financial institutions. As mentioned above, foreign investment has been negative over the past three years.

[image:12.612.158.466.420.602.2]The economy experienced significant structural change over the past 15 ye::irs, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: s」」エオイセャ@ Shares in GDP, 1985 and 2000

1985 2000 11. Agriculture, Forei;try and Fisheries i ! 23 17

2. Mining and Quarrying 18 13

13. Manufacturing Industry 16 26

4. Electricity, Gas and Water Supply

-

1js.Construction 51 71

16.Trade, Hotels and Restaurants

H

isl 17. Transport snd Communication_ J

5

18.

Finandal Smie<s 614 9

9.0ther Services

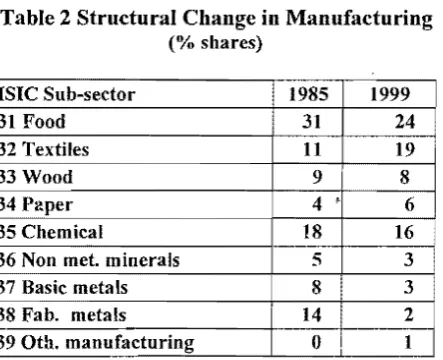

There was a degree of structural change within the manufacturing sector, with the export oriented textiles, garments and footwear sector increasing its share of MV A by 8 percentage points. Table 2 presents the structural change within manufacturing between 1985 and 1999.

•

Table 2 Structural Change in Manufacturing

(%shares)

ISIC Sub-sector 1985 1999 31 Food

セᄆᄆ]@

2432 Textiles 19

33 Wood 9 8

34 Paper 4 ' 6

35 Chemical 18 16

36 Non met. minerals ' 5 3

37 Basic metals • 8 3

38 Fab. metals 14 2

39 0th. manufacturing 0 l

•

As a signatory to the WTO, and more particularly due to its membership of ASEAN and APEC, Indonesia is a party to WTO, AFTA and APEC trade liberalization accords. Accordingly, it has pursued a policy of progressive liberalization of the trade and investment regime since the 1980s. Policies adopted since 1998, under the IMF Structural Adjustment Programme are further intensifying the irend to liberalizing the investment, trade and industrial licensing regime.

Table 3: MV A and Employment According to Size of Enterprise. 1996.

I Category of Enterprise % of Manufacturing % ofMVA I Employment

Large (>100 workers) 33.5 82.6

Medium (20-99 workers) 5.8 5.9

· - ·

-Small (5-19 workers) I 17.2 5.6

Household (<5 workers) 43.5 5.9

C. PRINCIPAL INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

The pre crisis industrialization trends, outlined in the preceding section, suggest that Indonesia was well on the way to developing a robust, competitive and diversified industrial sector and that the attainment of the status of a mid-income level industrialized economy, was foreseeable for the earlier part of the 21st century. Indonesia was considered among the prototype examples of countries that could benefit from the liberalization of trade and investment.

Closer examination, however, reveals several critical weaknesses in the manufacturing sector. Those weaknesses would, in all likelihood, have placed the country in a difficult competitive position, even if the crisis of 1997 had not occuned.2

2

[image:13.612.208.430.66.246.2] [image:13.612.134.490.399.485.2]First, manufacturing investment was undertaken by domestic and foreign firms with the primary objective of using the country's existing assets-fairly efficient labour, a wide range of natural resources, good infrastructure and good trading conditions-to develop Indonesia as a platform within existing international manufacturing and marketing chains. Even in cases where investors undertook industrial activity for the domestic market the presence of these same assets, along with growing domestic demand and implicit or explicit protection, were the mptivating force for investment. As a result, with a few exceptions, Indonesian manufacturing has yet to graduate from the assembly or basic transformation stages, with few fim1s taking the risks of product diversification or technological deepening.

Second, domestic entrepreneurs undertook manufacturing investment as part of a strategy to build diversified, multi sector business interests. Most of the Indonesian conglomerates hold business portfolios of firms in the plantation/primary commodities sector, in real estate, in manufacturing, in tourism, in financial services and to some extent in infrastructure. While· this strategy makes eminent sense as a method of rapidly accumulating capital across a broad front of activities, and diversifies business risk, it inhibits the processes of specialization, industrial innovation, the development of core competences of fim1s and, consequently, of the overali competitive advantage of the economy. Also, while foreign investors in the manufacturing sector undertook investments as part of their global manufacturing and marketi.ng strategies, there is little evidence of technology spin-offs or innovation in the domestic economy, although foreign O\vned firms tend to be more specialized than domestic conglomerates.

The consequence of these two factors is that the technological profile of Indonesian manufacturing remained stagnant between 1985 and 1997. The share of high technology industries in Manufacturing Value Added stayed constant, medium technology industries declined, and low technology industries slightly increased over the twelve years of rapid industrialization.

Third, related to the previous observation, entrepreneurship tended to adopt a herd instinct, concentrating on revealed business opportunities. There has been relatively little innovation and development of new markets and products. Consequently, the country has a very high degree of concentration of exported products and trading partners. Five manufactured products (plywood, textiles, garments, footwear and electronics) account for over half of manufactured exports. Three markets (the US, Japan and Singapore) account for over half of total exports. As a result Indonesian trade in manufactures is highly vulnerable to trends in the US and Japan; to competition from lower cost producers in textiles, garments and electronics, (China, South and South East Asian countries); and to the impact of the expiry of the Multi Fiber Agreement. The squeeze on corporate liquidity, imposed by the crisis, is an additional complicating factor as it will inhibit investment, over the next four or five years at least, in improving productivity and diversifying products and markets.

component of the country's recurrent current account deficit. The current account deficit was offset by substantial capital account surpluses accruing from external borrowing and private investment inflows. After the crisis, the current account deficit was transformed into a sizeable surplus due to a sharp collapse of imports. However there is reason to believe that the deficit will reoccur as Indonesia emerges from the crisis. The major difference will arise from the severely constrained prospects for public and private borrowing, a result of the large 、・「セ@ overhang, and a tepid inflow of foreign investment. Thus the country's future growth pattern threatens to demonstrate significant Balance of Payments deficits, in contrast to the pre crisis situation.

Fifth, as a result of the shallow, export oriented pattern of industrialization, and the essentially short term nature of business strategies, larger firms have not built domestic supplier and vendor networks, and they dominate the entire industrial spectrum As already noted, large scale industrial establishments produce about 83% of manufactured output whereas household, small and medium scale industries account for about 5-6% each of MV A. This is despite the numerous attempts by government to promote domestic sourcing to the small and medium scale sector. Government efforts to support the development of SME have been iimited to provision of credit and to fiscal or trade incentives. The development of technological or manufacturing capabilities of small firms has been largely unsuccessful as technological support institutions either do not exist or those which do exist have not become effective service providers to the privr..te sector.

Sixth, despite the preponderance of the number of SMEs, the sector is caught in a low-productivity equilibrium. While Small and Medium Scale manufacturing enterprises do account for a sizeable proportion of manufacturing employment, their contribution to manufacturing has been far more modest than their physical numbers would imply. They have made minimal contribution to growth in output, increase in productivity or the diversification of products and markets. Most SMEs in manufacturing are food processing and crafts based enterprises, or engage in the simplest levels of mechanized production. They· are heavily reliant on trading or distribution intermediaries for product development, marketing, raw materials, intermediate inputs and working capital. The consequence is that most of the family and small-scale manufacturing businesses operate in an environment resembling the "putting-out" system, in effect selling their skilled labour to larger entrepreneurs who assume business risk and intermediate between direct producers and markets. Few enterprises are able to innovate, leave alone expand their businesses to become players who can independently participate in domestic or international value chains.

Seventh, there is a threat of increasing environmental degradation and the deterioration of conditions of work as various regions of the country compete for domestic and foreign investment in a new regime of regional autonomy, which has come into force since January 2001. It can be imagined that the enforcement of enviromnental and labour standards as well as of regional minimum wages will be amongst the first victims of the competition among local govermnents in the effort to induce autonomous regional development.

other emerging economies in Asia. This decline manifested itself in the second half of the 1990s, three to four years before the financial crisis. After ウー・セエ。」オャ。イ@ growth of nearly 30% per annum in the late 1980s and early J 990s, manufactures' export earnings slowed down to a growth rate of 7% p.a., while those of the four major products (plywood, textile, garments and footwear) stagnated during 1993-97.

Following the 1997 financial crisis, the drastic devaluation of the rupiah (now worth only a quarter of its pre-crisis value) did not galvanize non-resource based manufactured exports. The now much lower labour costs (in dollar terms) have yet to have a major impact on Indonesia's competitiveness, since between 50 and 90% of the value of non- resource based manufactured exports consists of imported inputs, making export prices of these commodities largely impervious to the depreciation of the rupiah. The declining competitiveness is now manifesting itself on the domestic market. The financial crisis, and the ensuing IMF programme, has greatly increased pressure on Indonesia to further liberalize its domestic market, leading to the increased penetration of the domestic market by imported goods ranging from textiles and sandals, to motorcycles, hand tractors and consumer electronics.

The domestic manufacturing sector has been further weakened by corporate indebtedness. Domestic investment is dormant and flows of foreign direct investment have reversed, due to political and economic uncertainty and to serious competition in investment markets from China and other reform-oriented countries in the Asian region and dsev.rhere, with the result that there is very little, if any, investment being undertaken in the upgrading of teclmology 0r improving productivity.

The situation is further complicated by the slowdown or stagnation in major export markets, which will probably cause increasing competitive pressures as Indonesia and competitor countries struggle to maintain market share in the US and Japan, while trying to increase their shares of the regional market in Asia.

In summary, Indonesia has not graduated up the manufacturing value chain over the last fifteen years. Assembly based large-scale industries now face stiff competition in the international investment and product markets, creating a threat of industrial stagnation or even substantial de-industrialization.

D. COUNTRY STRATEGY, DEVELOPMENT OBJECTIVES AND

PRIORITIES

The installation of President Megawati Sukarnoputri and the formation of her cabinet, respectively on 23 July and 13 August 2001, inspired confidence that political and economic stability would be regained and sustained for the next three or four years, thereby permitting the adoption of medium to longer term policies and initiatives.

President Megawati has specified a six-point programme for her government in her speech of 13 August 2001, announcing the composition of the cabinet, i.e.:

• Maintaining national unity;

• Continuing the reform and democratization process; • Normalizing the country's economic life;

• Upholding the law, restoring security and peace, and eradicating corruption, collusion and nepotism;

• Restoring Indonesia's international credibility and regaining international confidence; and

• Laying the groundwork for the next general election in 2004.

These points establish the overall framework within which economic policies are being formulated.

On 14th of January 2002, at a cabinet meeting, the Minister of Trade and Industry presented a National Programme for the Revitalization of Industry. Covering the period 2002-2004, this programme is desigr1ed to revitalize and diversify industrial production. The overall motivating concerns of this policy are to increase exports, reduce unemployment and enhance food self-sufficiency in the economy. In addition the policy indicates concern over the weakness of supporting industries and the vulnerabilities of Smail and Medium Scale Industries. Three categories of sectors have been awarded special attention, ie.:

11 Industrial sectors requiring revitalization:

1) Textile and Textile Products 2) Electronics

3) Footwear

4) Processed Wood and Pulp/Paper

• Sectors requiring further development:

1) Leather and Leather Products 2) Fish Processing

3) Crude Palm Oil Processing

4) Fertilizers and Agricultural Machinery 5) Food Processing

6) Computer Software

7) Accessaries and Handicrafts

•

Supporting Industries that require further development:2) Leather processing (tanning)

The policy statement calls for · legislative, financial, investment support, trade promotion and infrastructure improvement measures to support the realization of production, export and employment targets to be achieved by the year 2004. Above all the industrial revitalization programme has been awarded the status of a national priority programme, requiring the commitment of all actors--the private sector, financial institutions, the support institutions and all concerned branches of Government-to achieve its production, export and employment targets.

E. EXTERNAL DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE AND DONOR

PRIORITIES

2001 external assistance to Indonesia is US$5.44 billion in pledges from the Consultative Group on Indonesia. That figure does not include pledges under the IMF structural adjustment programme. Leading multilateral donors are the Asian Development Bank (US$ 1.5 billion) and the World Bank (US$ l .3 billion).

Japan is the largest bilateral donor (US$1.8 billion), followed by the United States (US$280 million), Spain (US$ 73 million), Australia (US$ 64.7 million) and Germany (US$ 54.8million).

The UN system pledged a total of $146.75 million, with the World Food Programme (US$61.0 million), UNDP (US$ 41.9 million) and UNICEF (US$ 16.0 million) being the major players.

88% of external assistance is in the form of loans to the government and 12% (US$658 million) in the form of grants.

Before the crisis, much of the pledge was devoted to the core development agenda of developing the human resources, infrastructure, the productive sectors and trade related capacities of Indonesia. Since 1997, donor priorities have svrong towards welfare and governance related issues. Current donor priorities range from the provision of food aid, supporting the social safety net, to supporting more effective commercial law enforcement, development of civil society, supporting the

consolidation of democracy, the implementation of the law on decentralization,

conflict resolution, relief for internally displaced persons and relief and rehabilitation in conflict zones.

As regards the UN System, the United Nations Development Assistance Framework was formally issued in Augusi 2002, and the Government and the UN Country Team defined five priority Areas for UN System Operational Activities, i.e.:

a Governance and Institutional Reform;

• Sustainable and Equitable Recovery; • Social Justice and Poverty Eradication; and

CHAPTER II:

THE CURRENT UNIDO PROGRAMME

.

IN INDONESIA

A. OVERVIEW

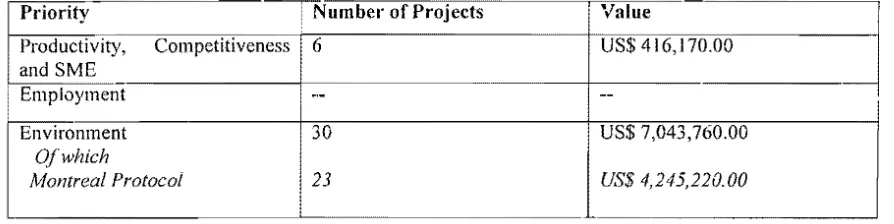

Between 1997 and 2002, UNIDO has mobilized US$ 7.5 million for 32 technical co-operation programmes or projects in Indonesia. These figures comprise projects undertaken nationally as well as regional or global lJNIDO implemented projects where Indonesia was a beneficiary country.

In terms of UNIDO's priorities, the breakdown of the projects is provided in Table 4 (see Annex l for List of Ongoing Programmes).

Table 4: Breakdown of UNIDO Programmes and Projects in Indonesia

Priority Number of Projects Value

Productiviry, Competitiveness 6 US$ 416,170.00 and SME

Employment I

--I ...

Environment 30 US$ 7,043,760.00 Of which

Montreal Protocol 23 US$ 4,245,220.00

The major funding source has been the Multilateral Fund, followed by UNDP/SPPD. Of bilateral donors, the Government of Switzerland fonded two important projects on tannery effluent control, and the Japanese government financed a feasibility study on Geothermal energy, through the UNIDO ITPO Tokyo.

B. LESSONS LEARNED

The major funding source has been the Multilateral Fund, followed by UNDP/SPPD. Of bilateral donors, the Government of Switzerland funded two importa.rit projects on tannery effluent control, and the Japanese government financed a feasibility study on Geothermal energy, through the UNIDO IPS Tokyo.

There are three major lessons to be learned from past patterns of funding of L1NIDO activities:

• There is a severe constraint on UNIDO's resource mobilization possibilities as

[image:19.612.91.538.402.514.2]the preponderant amount of ODA to Indonesia is in the form of loans rather than grants. This situation may change in the future if donors were, in the future, to relax their criteria for extemal assistance, given the difficult financial situation of the Govemment;

• The main multilateral financial institutions lending to Indonesia-the V/orld Bank and the Asian Development Bank-require UNIDO to enter competitive bidding processes for the implementation of their projects, and from first hand experience gained in the country, UNIDO is severely handicapped--in tem1s of procedures and human resources to--compete with private sector consultancies;

• Most major bilateral donors prefer to use their own implementing agencies (eg. OECF uses JICA, BMZ uses GTZ ... ) and those bilateral implementing agencies have large offices and presences in the country so they do not see, a priori, the need to work through UN agencies;

• The aftermath of the crisis caused a major shift in donor patterns away from a growth and deve!opment agenda towards a poverty alleviation and governance agenda. This creates a further disadvantage for a productive sector technical agency like UNIDO.

CHAPTER III:

THE UNIDO COUNTRY SERVICE FRAMEWORK

A. BACKGROUND

During his visit to Indonesia on 12 May 2001, the Director General of UNIDO proposed to the then Minister of Industry and Trade and to the Minister of Foreign Affairs that UNIDO prepare a Country Service Framework for Indonesia. Both Ministers welcomed the proposal. Since then, planning for this CSF was undertaken both at UNIDO headquarters and in the field.

Over the period August 2001-March 2002, the programming exercise was unde11aken and human and financial resources allocated to the formulation of this framework.

UNIDO CSF team missions to Jakarta took place in March and April 2002 (See Annex 2: Team Members of the CSF). The mission members met a total of about 150 people, representing the government, the private sector, universities, research institutions, non-governmental organizations, industry support institutions and the development cooperation agencies based in Jakarta. Those meetings enabled UNIDO headquarters staff to obtain a clear and up-to-date appreciation of country constraints. priorities and development efforts already underway.

fo addition to the findings of the missions, this CSF builds upon the UN country team priorities, analytical work and operational activities w1dertaken by the UN System and by UNIDO in Indonesia.

B. DURATION OF THE CSF

This CSF focuses on the period 2003-2004, which is the balance of the duration of the cunent National Development Plan as well as the remaining term in office of the current Govermnent. It will be reviewed at the end of 2004 for extension into the next cycle which will also coincide with the duration of the next National Development Plan so as to better reflect the development needs of the cow1try.

C. STRATEGIC THEMES/FOCUS OF THE UNIDO COUNTRY

SERVICE FRAMEWORK

• The need to support enhanced industrial competitiveness at a time that Indonesia faces competitive pressures from within the Asian region and elsewhere;

• To need to address the longer-term industrial development agenda in relation to its impact on poverty alleviation, whether through the development of small scale industry or thrpugh the development of agro industries or by supporting community recovery from the crisis;

• To need to pursue environmentally sustainable industrial development, as a response to regional or global concerns, or as a response to local problems.

These clearly fit into UNIDO's global priorities of improving industrial efficiency, enhancing employment and safeguarding the environment.

Based on these considerations, the country team defined two components under which UNIDO services could be offered to Indonesia:

• Component 1: Supporting the Development and Growth of SME; and

• Component 2: Supporting Energy Efficiency and Environmentally Sustainable Industrial Development

Component 1: Development of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises-Issues

and Justification

As earlier noted, despite the preponderance of the number of SMEs, the sector is caught in a low-productivity equilibrium. While Small and Medium Scale manufacturing enterprises do account for a sizeable proportion of manufacturing establishments, their contribution to manufacturing has been far more modest than their physical nu..rnbers would imply. They have made minimal contribution to growth in output, increase in productivity or the diversification of products and markets. Most SMEs in manufacturing are food processing and crafts based enterprises, or engage in the simplest levels of mechanized production. They are heavily reliant on trading or distribution intermediaries for product development, marketing, raw materials, intermediate inputs and working capital. The consequence is that most of the family and small-scale manufacturing businesses operate in an environment resembling the "putting-out" system, in effect selling their skilled labour to traders who assume business risk and intermediate between direct producers and markets. Few enterprises are able to innovate, leave alone expand their businesses to become players who can independently pa1ticipate in domestic or international value chains.

fiscal or trade incentives. The development of technological or manufacturing capabilities of small firms has been largely unsuccessful as technological support institutions either do not exist or those which do exist have not become effective service providers to the private sector.

As a consequence, household, small scale and medium scale enterprises account for only about 6% each of the value of total manufact9ring output while employing respectively 44%, 17% and 6% of the manufacturing work force.

UNIDO's response under this component is five fold. First, UNIDO will attempt to facilitate conditions of transactive efficiency for the small and medium scale industrial sector, by analyzing trading bottlenecks and proposing public policy measures to enhance the trading capacity of the industrial economy. Second, U1\-IDO will implement demonstration projects that will empower clusters of SMEs to initiate mutually beneficial actions which could enhance their competitive efficiency. Third, UNIDO proposes the initiation of a progran1me to create technology and investment partnerships for agro based SMEs, which could enable them to enhance their technological capabilities and widen their access to markets. Fourth UNIDO will suppo1i the emergence of new technology based SME sectors by building Indonesia's capacities in the field of Technology Foresight. Finally, through the transfer of project feasibility tools to banks and SME support institutions in Indonesia, UNIDO will facilitate SMEs access to credit by enabling them to present feasibility studies developed according to international standards while enabling Banks to evaluate the creditw01ihiness of those studies according to the san1e standards and methodologies. In this way the Organization will supplement domestic efforts by providing investment, technological and business support services in this sector.

Component 2: Energy Efficiency and Environmentally Sustainable Industrial

Development---Issues and Justification

The rapid pace of economic growth and recent economic turbulence pose a significant threat to the Indonesia's abundant environmental resources. While inter-sector comparisons ace difficult, the iarge-scale manufacturing industry is probably not the greatest cause of environmental stress, as the capital stock of such industry is of relatively recent vintage, with environmental safeguards built into the engineering design of machines and equipment. Also, large-scale manufacturing is subject to a fair degree of supervision by government for compliance with national environmental performance standards. Larger scale export oriented industries are also subject to environmental compliance standards set by foreign principles, buyers and customers. The present situation may, however, deteriorate in the future, as government supervision may become weaker and as the manufacturing sector faces increased competitive pressure.

Fossil fuels are projected to constitute 40 per cent of the energy mix by 2021, and energy demand is likely to grow at 5.5 per cent p.a. This will greatly increase emissions of particulate matter and greenhouse gases.

The adverse impact of informal sector and illegal mining (such as mercury used in artesanal gold mining, leaching into soils and subterranean aquifiers and runoff into rivers and coastal waters) has also become a major concern, as has the use of cyanide and dynamite in coastal fishing. These affect inland waters, riverine and coastal ecosystems, and threaten human health.

The currency devaluation has shifted the country's competitive advantage to resource-based industries, the uncontrolled expansion of which can have severe environmental consequences. A recent newspaper article puts it succinctly, "Forest Watch Indonesia, a forum of 20 NGOs committed to investigating the status of Indonesian forests, in 2002 reported that since 1996 the deforestation rate has been around two million hectares per year. In 1980, the deforestation rate was estimated at around one million hectares per year, in the 1990s the deforestation rate was 1.7 million per year. And the rate is increasing year-by-year. .. The World Bank estimates that in 2005 the lowland forest in Sumatra will be gone and the lowland forest in Kalimantan will be gone by 2010".3 Pulp and paper, timber and plantation companies, which enjoy favourable international competitive position and buoyant demand in export markets, undertake most of the clearing of forests.

The environmental problems confronting the country are indeed large and complex. In response to these challenges, UNIDO proposes a three-pronged approach under this component. First, the Organization proposes to undertake pilot projects for alternative energy or environmentally efficient energy technologies; second it proposes to undertake demonstration projects to reduce em1ssi0ns and pollutants in environmentally sensitive industries such as the tanning industry; and third it will support technological transformation in certain sectors where Indonesia is obligated to protect the Global Commons under various international environmental conventions.

It needs to be noted that the size and diversity oflndonesia' s industrial sector demand a degree of selectivity in determining issues that need to be addressed by LTNIDO. The Organization's limited human and financial resources in relation to those of the several larger development partners in Indonesia, dictate that UNIDO's suppo1i has to be strategic and/or of a pilot nature, with the intent of developing and demonstrating innovative approaches to problems addressed.

Also, the preponderant influence of the private sector in Indonesian industry make it a central actor in our activities, whether as a beneficiary of UNIDO eff011s or as a development partner along with the Government Ministries and Agencies. Over the years, in Indonesia and internationally, UNIDO has been able to network with important private sector players and NGOs, and these networks are a source of contacts, capabilities and knowledge that the Organization can bring to bear on the development issues addressed in Indonesia.

J The reader is referred to Harry Surjadi, Journalist, Jakarta, "Indonesia's biodiversity will be gone in

Finally, given the decentralization of the fiscal, administrative and developmt:mtal responsibilities of government, UNIDO interventions should solicit the greatest possible involvement of local governments and development partners at the provincial level.

D. MAIN PROGRAMMES PROPOSED

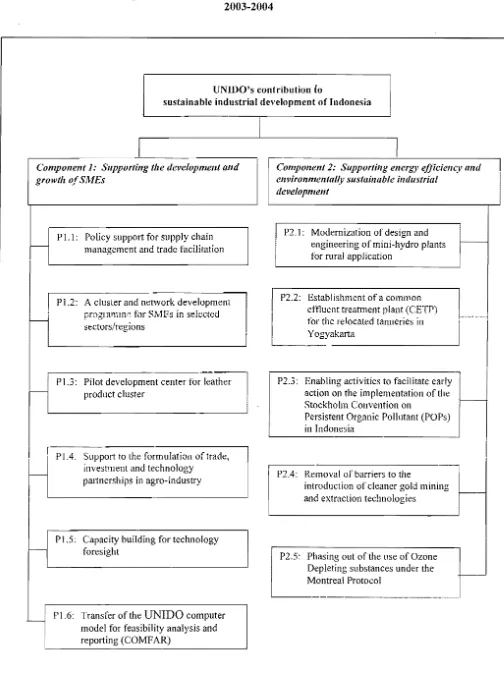

Based on the above components and UNIDO's prior activities in the country, as well as the result of the programming mission, the country team defined eleven programmes that form this CSF. Of these eleven, 4 are continuations or extensions of UNIDO's prior activities, and seven "new" initiatives are proposed. The structure of the CSF and its programmes are represented in the figure 1 below.

The rest of this section briefly outlines the objectives of each of the 11 programmes of the CSF.

Component 1: Support to tlze Development of Small and Medium Scale

Industry:

Programme 1.1: Policy Support for Supply Chain Management and Trade Facilitation

It has been argued in the introductory section of this· CSF that Indonesia will face increased competitive pressure in investment as well as products markets, over the foreseeable future. The retention of competitive advantage will depend as much on the efficiency of Indonesian firms, as it will on the trading and transactional efficiency of the Indonesian economy. This programme is intended to examine and address the latter aspect. To put matters in perspective, anecdotal evidence appearing in the press over the last few years suggested that non-factor and other transaction costs add up to 30 per cent of ex-factory costs in some industrial branches, in Indonesia. In the. United States, by contrast, logistics and transaction service costs amount to only l 0 per cent of the vaiue of output.

In Indonesia, these costs assume significance when contrasted to labour costs, which amount to only 7 per cent of the gross value of manufacturing output, and in even such labour intensive industries as garments and footwear manufacture, they absorb only 12-13 per cent. It can be argued, therefore that a greater transaction efficiency, improved infrastructure, trade administration and so on, would have a greater impact on competitive efficiency than would movements in labour costs.

Figure 1: Country Service Framework for Indonesia 2003-2004

I

UNIDO's contribution fo

sustainable industrial development of Indonesia

I

I

Component 1: Supporting the development and growth of SMEs

Component 2: Supporti11g energy eb7cie11cy mu/ environmental(v sustainable imlustrial

development

-P 1.1: Policy support for supply chain management and trade facilitation

I

Pl .2: A cluster and network development pr:1gramme fo1 SMEs m sekcted sectors/regionsPl.3: Pilot development center for leather product cluster

P 1.4: Support to the formulation of trade,

investinent and technology pai1nerships in agro-industry

Pl .5: Capacity building for technology foresight

Pl .6: Transfer of the UNIDO computer model for feasibility analysis and reporting (COMFAR)

i

P2. J: Modernization of design and engineering of mini-hydro plants

! for rural application

P2.2: Establishment of a common effluent treatment plant (CETP) for the relocated tanneries in Yogyakarta

-L

I

LNMMセセセセセセセセセセセセセセセMセ@

P2.3: Enabling activities to faciiitate early action on the implementation of the Stockholm Convention on

Persistent Organic Pollutant (POPs) in Indonesia

P2.4: Removal of barriers to the

introduction of cleaner gold mining and extraction technologies

P2.5: Phasing out of the use of Ozone Depleting substances under the Montreal Protocol

[image:26.612.63.567.80.769.2]-More importantly, it would furnish a basis on which specific policy and administrative measures could be undertaken to improve overall economic efficiency of production and trade, while developing a methodology by which the private and public sectors could extend this policy related analysis to other industrial sectors. This approach to enhancing efficiency of transactions is not just a matter of better economics. There is a social concern that could be met here. The reduction of ex factory transaction costs would free up more resom;ces for firms to invest in the improvement of worker skills, the quality of jobs and wage rates.

Programme 1.2: A clusters and networks development programme for SMEs in selected sectors/regions

The programme is intended to demonstrate the effectiveness of UNIDO's approach to enhancing the competitiveness of selected clusters of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Indonesia. This objective will be achieved by means of the established UNIDO methodology to increase the collective efficiency of such clusters through increased collaboration and networking between various cluster actors, including the entrepreneurs themselves, their representative organizations, and various public-and-private sector development agencies. Speciaily trained cluster development agents in the various clusters will undertake a diagnostic of their respective clusters, through close consultation with the cluster actors, to identify weak.llesses and strengths of those clusters. Joint action plans will formulated in order to enable the various cluster actors to overcome the constraints and seize the opportunities revealed by the diagnostic study. The action plan, in turn, provides the basis for the formulation and execution of specific initiatives over the remainder of the programme period to address the various individual points raised by the diagnostic survey.

As in the other countries, the success of this programme would build capacities in Indonesia for the government and the private sector to form public-private partnerships to enhance the competitiveness of SME clusters. A practical demonstration would thus have been provided to realize the Government's overall policy of emphasizing SME development and on strengthening industrial clusters in Indonesia.

Programme 1.3: Pilot Development Center for Leather Products Cluster

Despite the large volume of exports from Indonesia, large-scale athletic footwear producers do job work, product designs are supplied by foreign partners and marketing is also in the hands of the latter. Indonesian manufacturers will probably lose their partners (multinational brands) when other - even cheaper and perhaps safer - countries offer better conditions. Without assistance in marketing, prnduct development and quality assurance there is a threat to the 400,000 jobs created in this branch by large and medium enterprises .

as part of a countrywide network. It will identify the region/cluster where the pilot centre should be established, assess local needs and availability and quality of design and marketing services (e.g. FSC, IRDLAI, universities). It will prepare a feasibility study on the future operation of the centre, spelling out different options of ownership and operations. Once the organizational details are worked out it will provide the requisite hardware, software and information and training support to establish a fully operational product design and development servii;e center for the benefit of enterprises participating in the creation of this service center.

Programme 1.4: Support to the formation of Trade, Investment and Technology Partnerships in Agro Industry

Almost all of the investment flowing to Indonesia was transacted by large-scale industry, whether foreign multinationals seeking to operate in Indonesia as part of their global strategies, or domestic conglomerates seeking joint ventures with foreign pai1ners, as sources of product or market development and technology. Small and medium scale enterprises are left out from participating in international value chains, in international transfers of technology and in partnerships for product innovation for domestic and export markets. This programme aims to strengthen the country's institutional support capacities in selected regions (provinces/districts) in the promotion of trade, investment and technology partnerships between Indonesian SMEs and specialized foreign companies. It will concentrate on selected industrial branches drmvn from the agro industrial sector. Through the development, promotion and brokering of such pa11nerships, the activity will contribute to a more balanced regional development via rural employment creation and income generation and thus contribute to the alleviation of poverty.

The programme will encompass (i) the estabiishment of a business partnership promotion and matchmaking unit, (ii) capacity building on the part of trade, investment and technology promotion agents to facilitate successful matchmakings, covering topics such as organizational and operational strategies for trade/investment promotion entities; trade/investment promotion techniques and skills; investment project preparation and appraisal, applying UNIDO' s established format, tools and methodologies; joint ventures and strategic partnerships; technology transfer operations, agreement formulation ai1d negotiation; or technology needs assessment and benchmarking, (iii) the rendering of ad-hoc advice and hands-on guidance to Indonesian SMEs in the preparation of international business tie-ups, (iv) the identification, formulation and appraisal of specific matchmaking opportunities in trade, investment and technology and their subsequent focussed promotion in key foreign markets, including through UNIDO's network of Investment and Technology Promotion Offices, and (v) support to local companies entering into business negotiations with potential foreign partners.

Programme 1.5: Capacity Building for Technology Foresight

system of innovation in reiation to indigenous R&D capabilities. In seeking an appropriate solution to the above issues Technology Foresight offers an effective instrument to capture complex variables and provide a durable basis for developing industrial policy. TF helps to identify possible future development scenarios to: improve short, medium, long-term decision making; guide technology choices; generate alternative trajectories for development; improve preparedness for emergencies and contingencies; motivate change and innovation; and achieve broad consensus and strategic commitments. •

The main objectives of the UNIDO programme will be to facilitate the identification of technologies in selected industrial sectors which could strengthen national competitiveness, to enable the national products to better access the regional and the global market, to build capacity at industrial level to identify risks and opportunities on how to improve value chain competitiveness.

The project wili expose national decision-makers from government, industry, academia and industry support institutions to TF process and methodologies, such as Delphi, scenario writing, SWOT, etc. The process will also assist in clarifying future challenges and prospects and opportunities and will identify what government and industry can do, and should be doing, to meet and take advantage of TF outputs in order to achieve sustainable growth of industrial development from resource-based industry to more technology-based industry. In this way, it will enable both the government and private sect1Jr to define industrial policy and investment strategies. in order to ・ョ。「ャセ@ Indonesia to graduate from a labour or resource based economy to a technology and knowledge based one. As mentioned before, given Government priorities, the emphasis and intended target beneficiaries of this exercise will