A Quantitative Examination

Aviv Shoham

ISRAELINSTITUTEoFTECHNOLOGY

Gregory M. Rose

UNIVERSITYoFMISSISSIPPILynn R. Kahle

UNIVERSITYoFOREGONThe consumption of risky sports continues to grow. Risky sports include awful fall stops. The much-anticipated tap of Mordi on my shoulder starts 40 seconds of pure happiness . . . I am

activities such as skydiving, deep-sea diving, and parachuting that entail

a high level of physical risk. To date, most studies of risky sports have engulfed with optimism, screaming with the feelings of

tended to be more qualitative than quantitative and were based on partici- freedom and liberation. An addictive sensation. Birds feel

pant observation. The research described here builds on earlier research similarly [(Zundar, 1995), p. 68].

by integrating the frameworks within which risky sports’ consumption have been documented—drama, danger neutralization and peer identifi-cation, and extraordinary experiences—into an empirically testable

T

his first skydiving experience described by an Israelimodel. The model is tested on the basis of responses from 72 individuals,

journalist is similar to that discussed by Celsi, Rose,

who have been active in sports such as deep-sea diving, parachuting, and

and Leigh (1993). Similar sensations of fear

trans-rock or mountain climbing. Substantial empirical support is found for the

formed into happiness have been described for river rafters

integrated, drama- and extraordinary-based frames of reference. The

(Arnould and Price, 1993; Arnould, Price, and Tierney, 1998a,

findings are used to generate managerial implications, a topic mostly

1998b; Price, Arnould, and Tierney, 1995) and Canadian

neglected in previous research.J BUSN RES2000. 47.237–251. 1999

hang gliders (Brannigan and McDougall, 1983). Many leisure

Elsevier Science Inc.

activities involve some level of physical risk. Risky sports differ from other sports in that consumers knowingly face the risk The plane climbs slowly, until it reaches 11,000 feet. The

of a serious injury and even death when judgment or equip-door opens, and a wave of fear strikes me. A strong, very

ment fail (Lyng, 1990). Annual deaths range between one of cold gust rushes inside and makes me jam into a corner.

250 ultra-light airplane pilots to one of 100,000 scuba divers, I try to remember the instructions . . . Another second,

the latter still twice the rate for football players (Celsi, Rose, and Mordi [the instructor] jumps. We are falling. The wind

and Leigh, 1993). hits us and overpowers my facial muscles. I think that one

Risky sports are increasingly practiced in developed na-cheek engulfs an ear. A sharp pain shoots through my

tions. This increase is due to the juxtaposition of a dramatic lower stomach. The amazing speed of the fall accumulates.

world view, perpetuated by the mass media, with the special-Something very bad is happening. Mordi is late or has lost

ized and bureaucratic social forms of the twentieth century. control . . . Just then, not more than five seconds since we

Thus, risky sports may provide a release from the tensions of left the plane, Mordi opens the tiny balancing canopy. The

the modern era. The popularity of risky sports has created market opportunities for emergent industries, such as clubs,

Aviv Shoham is a lecturer of marketing at the Faculty of Industrial Engi- equipment stores, and magazines. The interest of marketing neering and Management, Technion–Israel Institute of Technology,

Tech-scholars in the study of risky sports parallels the

populariza-nion City, Haifa, Israel. Gregory M. Rose is an Assistant Professor of Marketing

at the University of Mississippi, University, Mississippi. Lynn R. Kahle is the tion of these sports. Prior research has described the experi-James H. Warsaw Professor of Marketing at the University of Oregon,

Eu-ence of rafting, hang gliding, and skydiving (Arnould and

gene, Oregon.

Address correspondence to Dr. Aviv Shoham, Technion–Israel Institute Price, 1993; Brannigan and McDougall, 1983; Celsi, Rose, of Technology, Faculty of Industrial Engineering and Management, 32000

Technion City, Haifa, Israel. and Leigh, 1993; Celsi, 1992) and has provided thick

descrip-Journal of Business Research 47, 237–251 (2000)

1999 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0148-2963/00/$–see front matter

tions of the hedonic aspects of risky sport consumption. Ar- viewed as a need for thrill, adventure, and novel experiences nould and Price (1993) and Celsi, Rose, and Leigh (1993) (Zuckerman, 1983, 1984; Zuckerman, Buchsbaum, and Mur-use induction to suggest two frameworks for understanding phy, 1980; Zuckerman, Kolin, Price, and Zoob, 1964). It is the seeming paradox between rational behavior and the con- trait-based in that individuals have given levels of needs for sumption of risky sports. They link the transcendent nature sensation. The scale for measuring sensation seeking (SSS-V; of risky sport to increased participation (Celsi, Rose, and Zuckerman, 1979) includes sub-dimensions for thrill and ad-Leigh, 1993) and satisfaction (Arnould and Price, 1993). Indi- venture seeking, experience seeking, boredom susceptibility, vidual and group variables are combined with insights from and disinhibition. The scale exhibits acceptable reliability and the extraordinary experience model to provide an excellent convergent validity (Wahlers, Dunn, and Etzel, 1986; Whalers basis for a managerially oriented, empirical examination of and Etzel, 1990). Sensation seeking has been linked to higher this paradoxical consumer behavior. consumption of drugs, smoking (Burns, Hampson, Severson, This article explores the frequency of participation in risky and Slovic, 1993; Severson, Slovic, and Hampson, 1993), sports. It synthesizes findings from previous research into an and risky sports (Hymbaugh and Garrett, 1974; Zuckerman, empirically testable model. The framework used here inte- Buchsbaum, and Murphy, 1980).

grates the drama-form (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh, 1993), danger- Telic dominance, a state-based theory, is a second theory neutralization and peer-identification explanations (Brannigan used to explain the probability of engaging in risky sports and McDougall, (1983), and the extraordinary experience (Apter, 1976, 1982; Smith and Apter, 1975). It has been model (Arnould and Price, 1993; Price, Arnould, and Tierney, operationalized by measuring individual differences based on 1995). We adopt a managerial focus in developing our model. one’s propensity toward two stable states (telic and paratelic). Arnould and Price (1993) and Price, Arnould, and Tierney The dominance of either of these states has been viewed as a (1995) focus on the attitudinal outcome of satisfaction. We personality trait (Murgatroyd et al., 1978). In a telic state, examine the behavior (frequency of engagement in current individuals try to gain arousal (felt as pleasant); in a paratelic risky sports) and future behavioral intention (probability of state, individuals try to reduce arousal (seen as unpleasant). entering other risky sports). The frequency of risky sport’s While telic dominance and reversal theory, on which it is practice can be used in segmentation and positioning by iden- based, are state-based, the Telic Dominance Scale assesses tifying the characteristics and preferences of heavy versus light three trait sub-dimensions: arousal avoidance, serious-mind-practitioners. The probability that practitioners of one risky edness, and planning orientation (Murgatroyd et al., 1978). sport will enter into others is also managerially relevant, be- Telic dominance and arousal avoidance differ between risky cause if engagement in new risky sports is predicated on sports practitioners and the general population (Kerr, 1991). similar explanatory constructs as participation in current risky In marketing, sensation seeking and telic dominance be-sports, then firms catering to one risky sport could target long to studies of optimal stimulation levels. These studies practitioners of other risky sports. As previous research has assume that there exist one (homeostatic) level of sensation mostly ignored managerial implications, generation of such or two (bi-stable) levels of stimulation (telic or paratelic) with implications is an important part of this article. which individuals are comfortable. Deficiency or surplus of Theoretically, sensation seeking and risky sport consump- environmental stimulation will result in individual behavior tion are frequently treated as stable traits. However, skydiving to increase or reduce stimulation (Raju, 1980; Wahlers and motivations evolve over time. While an individual may initially Etzel, 1990).

join to comply with a friend’s request, efficacy, identity-con- The purpose of this study is to identify differentiating fac-struction, higher-order group motives, such as communitas, tors for individuals, who already practice risky sports. Such become more important over time. Thus, empirically examin- individuals are expected to score high on sensation seeking ing the association between various needs and motives for and low on arousal avoidance. Although sensation seeking participating in risky sports and the expected probability of and telic dominance have been used mostly to predict risk-participating in other risky sports should help identify the taking behavior in the general population, we use them to extent to which specific needs are sport-specific, providing establish validity. Comparing sensation seeking in our sample additional evidence in the trait versus process debate. with levels in previous studies can substantiate the generaliz-Finally, we use an Israeli sample of practitioners. This choice ability of our findings. Furthermore, inclusion of the two should help to extend the generalizability of findings from scales can be used to identify sub-populations within risky previous research beyond the U.S. samples used in the past. sport practitioners.

We synthesize findings from Celsi, Rose, and Leigh (1993), Brannigan and McDougall (1983), Arnould and Price (1993),

Theory and Research Hypotheses

and Price, Arnould, and Tierney (1995). They view risky sport participation as a continuous process and describe the Substantial research on joining risky sports is based on twoevolution of motives throughout this process. We integrate theories. The first is a trait theory based on an individual’s

sports. This model has an advantage in that comparisons can (Bandura, 1965; Brannigan and McDougall, 1983; Celsi, Rose, be made within the group of practitioners. All three ap- and Leigh, 1993).

proaches share four building blocks, which explain the con- Arnould and Price (1993) also argue for the importance sumption of risky sports: the need for identity construction, of efficacy. River rafting guides help rafters acquire new skills. efficacy, camaraderie, and experience. We examine each of Progressive mastery continues throughout the rafting trip. the four separately, although they are related. Because of its long duration, one river rafting experience af-fords the individual an opportunity to satisfy needs for efficacy within a single trip. In contrast, similar needs are satisfied

Identity Construction

over multiple consumption activities for skydivers due to the Celsi, Rose, and Leigh [(1993), p. 11] discuss identity

con-short duration of a jump. In both cases, the need for efficacy struction as a motive for continuous involvement in risky

is a motive for continuous involvement. Thus: sports. They refer to this opportunity as “. . . a well-defined

context for personal change, as well as a clear-cut means to H2: The relationship between the perceived satisfaction of organize a new, and sometimes central, identity.” Initiation efficacy needs in a risky sport and both the frequency is a structured process, similar to a pilgrimage (Arnould and of engagement in it and future probability of engaging Price, 1993) or rite of passage (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh, 1993). in other risky sports is positive.

Participation in the sport is seen as special or unique. This

structured opportunity for self-construction through a unique,

Camaraderie

extraordinary experience provides a powerful motive in theThe importance of the group within which a risky sport is late twentieth century, where adult roles are frequently

rou-practiced is an additional motive for practicing it. Celsi, Rose, tine, bureaucratic, and hard-to-change.

and Leigh [(1993), p. 12] use group camaraderie as one of Arnould and Price (1993) identify extension and renewal

three transcendent motives-flow, communitas, and phatic of self as a theme associated with satisfying river rafting trips.

communion. They define communitas as “a sense of commu-Part of this growth is acquiring a new sport-specific jargon.

nity that transcends typical social norms and convention.” It Newcomers to ultra-light plane flights start using terms such

provides a sense of camaraderie for people from differing as “air pocket,” “lower the nose,” “throttle,” and “flaps” (Kafra,

backgrounds; they can regard their joint activities as sacred 1995). Skydivers use “free fall,” “secondary canopy,” and

(Belk, Wallendorf, and Sherry, 1989). Communitas develops “main canopy” (Zundar, 1995). The new terms are used to

when shared experiences transcend the drudgery of everyday signify one’s membership, acceptance, and understanding of

life and provide shared rituals or extraordinary experiences. the special viewpoint of risky sport participants (Celsi, Rose,

Group members recognize the irrelevancy of external roles and and Leigh, 1993). Price, Arnould, and Tierney (1995) used

develop expertise and specialized roles within the community, identity construction as a measure of provider performance,

maintaining the separation between the everyday world and which led to satisfaction. Brannigan and McDougall (1983)

the extraordinary risky sport experience. identify the ego-gratifying aspects of continuous involvement

Arnould and Price (1993) include communitas as a theme in risky sports. Ego gratification results from internal,

sub-of satisfying rafting trips. In the process sub-of negotiating white-culture-based status and from external, media-based attention.

water rivers, team members develop feelings of belonging to In sum, given identity construction’s important role in

the group. The group is united by its devotion to a single, explaining continuous risky sport participation and

satisfac-transcendent goal. In the process, rafters dispose of personal, tion, it is hypothesized that:

non-task-related possessions, in favor of shared and

goal-H1: The relationship between the perceived satisfaction of relevant ones. The process is aided by rafting guides, who identity construction needs in a risky sport and both provide reinforcement for teamwork. Consequently, Price, the frequency of engagement in it and future probabil- Arnould, and Tierney (1995) use a measure of the service ity of engaging in other risky sports is positive. provider having created a team spirit in their performance

scale. Positive social relationships serve to reinforce participants’

Efficacy

continuous involvement (Brannigan and McDougall, 1983). Communitas is manifested in identity construction and Celsi, Rose, and Leigh [(1993), p. 10] suggest efficacy as aefficacy in the drama form (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh, 1993), the motive for “sticking with it.” They define the need for efficacy

danger neutralization and peer identification (Brannigan and as “a desire to develop technical skill for both personal

satisfac-McDougall, 1983), and the extraordinary experience models tion and social status within the sky-diving community.”

Con-(Arnould and Price, 1993; Price, Arnould, and Tierney, 1995). sumers are motivated to stay involved with the sport because

Initiation processes in the pilgrimage metaphor (Arnould and they get getter at it (Branningan and McDougall, 1983).

Fur-Price, 1993) and in rites of passage (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh, thermore, standards shift and become more demanding with

1993) are important aspects of satisfaction of identity con-increased expertise. Thus, self-expectations increase with

H4b: The relationship between the experience in a risky groups with common interests and goals. Further, efficacy

sport and the future probability of engaging in other involves the development of sport-related skills and expertise

risky sports is negative. (Arnould and Price, 1993). Such skills differentiate the

experi-enced from novices and from non-participants. Efficacy con- Finally, we controlled for age in our analyses because it tributes to one’s standing within the community. In sum, the can have opposite effects. Older people may not be as fit for group motivates members to continue and increase their level the physical demands of many risky sports. Therefore, the of involvement: frequency of practice of the sport and the probability of

enter-H3: The relationship between the perceived satisfaction of ing new risky sports in the future should decline with age. camaraderie needs within a group of practitioners of In contrast, some of the needs Celsi, Rose, and Leigh (1993) a given sport and both the frequency of engagement discuss may be more important for older individuals. They in it and future probability of engaging in other risky have had more opportunity to face the tension emanating sports is positive. from the workplace, causing them to look for the release and catharsis that can be gained from a risky sport. Older people

Experience

may also have had more years to develop the skills relevant to risky sports, thus reducing the risks. Given these conflicting The importance of experience in determining present androles, age is used as a convariate, and no hypothesis is ad-future behavior is multi-faceted. It runs through Celsi, Rose,

vanced about its effect. and Leigh’s discussion (1993) of the need for efficacy and

To sum, perceived fulfillment of identity construction, effi-identity construction. Efficacy is predicated on developing the

cacy, and camaraderie needs by a risky sport affects the fre-prerequisite technical skills and jargon of the sport. During

quency of engagement in it and the probability of engaging this process, attention shifts from anxiety about the physical

in other risky sports positively. The relationship between expe-risks involved in the sport to achieving greater performance

rience is a risky sport and the frequency of engagement is through the successive mastery of greater challenges (Celsi,

Rose, and Leigh, 1993). also positive, but the future probability of engaging in other The importance of experience is also evident in the process risky sports is negative.

of identity construction. Sustained participation provides an individual with an opportunity to construct a new self (Belk,

Methods

1988). The opportunity to construct a new self depends onsufficient commitment to a new set of life tasks with associated

Pretest

plans for implementation. Sticking with the sport (Celsi, Rose,The pretest involved two stages. First, interviews were held and Leigh, 1993) is a form of such commitment. Arnould and

with practitioners of risky sports to assess the appropriateness Price (1993) trace the evolution of three themes over the river

and clarity of the questionnaire. Then, the revised question-rafting experience. Communitas, communion with nature,

naire was tested on a sample of 60 students. Since the question-and extension question-and renewal of self make river rafting an

extraor-naire included items about non-risky sports as well, reliability dinary experience. Each of these themes changes as the trip

and validity of the various measures could be assessed by use progresses because opportunities for their manifestations

ac-of responses to the non-risky sport scales. Respondents were cumulate. As the rafting trip draws to an end, “participants’

also asked to comment on the clarity of the instructions and embodiments of communitas become particularly evident and

items. Examination of these responses resulted in a few striking. [Field notes] disclose the depth of emotional

attach-changes. Some items were deleted, others were replaced or ments formed among the members of the trip” [Arnould and

re-phrased, and new items were added. Additionally, a few Price (1993), p. 35].

introductory questions were re-worded to clarify the instruc-In sum, experience plays a role in risky sport consumption.

tions to respondents. Celsi, Rose, and Leigh’s (1993) satisfaction of participants’

motives and Arnould and Price’s (1993) evolution of themes

Sample

are related to experience. Sport-specific expertise and

experi-ence is a progressive process—successive stages of mastery Data were collected in a survey of risky sports practitioners lead to a desire for greater challenges (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh, in Israel. Respondents were active participants in at least one 1993). Thus, experience should be related positively to the of the main risky sports practiced in Israel: skydiving, rock and frequency of engagement. Experience in a given sport, how- mountain climbing, deep-sea diving, and gliding. Potential ever, should be related negatively to the probability of con- participants were identified either through professional guides sumption of other risky sports. Experience and expertise in or through national associations of the sports.

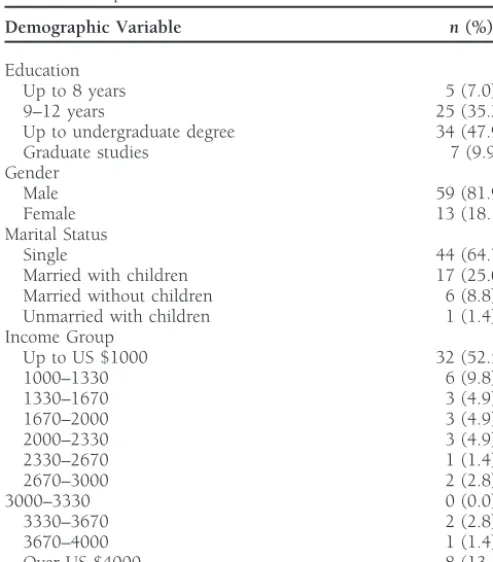

one sport are not transferable, which forces an individual to The sample (Table 1) includes more males (59, or 81.9%) start participation in any new risky sport from scratch. In sum: than females (13, or 18.1%). Most individuals have an

under-graduate degree (47.9%), followed by high school under-graduates

H4a: The relationship between the experience in a risky

Table 1. Sample Characteristics and 25 gliders. Finally, 27 risk-preferring individuals were

used in a sample. Calls to a sample of non-respondents yielded

Demographic Variable n(%)

questionnaire length (15 pages) as a main reason for

non-Education response.

Up to 8 years 5 (7.0)

9–12 years 25 (35.2)

Development of Measures

Up to undergraduate degree 34 (47.9)

The first step involved a development of multiple items for

Graduate studies 7 (9.9)

Gender the study’s constructs based on a literature review. Two

schol-Male 59 (81.9) ars from the United States and one from Israel developed the

Female 13 (18.1)

items in English. The items were translated from English to

Marital Status

Hebrew by one bilingual individual and back translated by a

Single 44 (64.7)

second bilingual individual. Instructions to the two

individu-Married with children 17 (25.0)

Married without children 6 (8.8) als emphasized the need to create equivalency on four dimen-Unmarried with children 1 (1.4) sions: functional; operationalization; items; and scalar (Hui Income Group

and Triandis, 1985). The two English versions were compared

Up to US $1000 32 (52.5)

by a third bilingual individual (Brislin, 1970). Changes were

1000–1330 6 (9.8)

1330–1670 3 (4.9) made by consultation of the three individuals. The items and

1670–2000 3 (4.9) alphas for the scales are reported in the Appendix.

2000–2330 3 (4.9) Analyses of the items and exploratory factor analyses were

2330–2670 1 (1.4)

used to clarify the scales. Items with high factor loadings and

2670–3000 2 (2.8)

item-to-total correlations were retained. This resulted in the

3000–3330 0 (0.0)

3330–3670 2 (2.8) use of three items for the potential of the risky sport to satisfy

3670–4000 1 (1.4) the need for efficacy, four for the need for identity construc-Over US $4000 8 (13.1) tion, and three for the need for camaraderie. The three scales

were subjected to confirmatory factor analysis to establish

Note: Percentages do not add to 100.0 due to rounding off. Sub-sample sizes do not

add up to 72 due to a few missing values. unidimensionality (Gerbing and Anderson, 1988). Due to

sample size, separate analyses were performed for each scale. In each, only one factor emerged and all items had high (9.9%). Most are unmarried and have no children (64.7%), loadings on the single factor.

but married with children are also represented (25.0%) as are Experience and age were measured by open-ended items. married with no children (8.8%) and unmarried with children The two measures should be highly correlated. This is because, (1.5%). Income is bimodally distributed with 52.5% at the other things being equal the older the respondent, the longer lowest end of the scale (up to $1000 gross per month), 9.8% his (her) potential experience in the sport. This indeed was just above the lowest ($1000–1330 gross per month), and the case, as the two are highly (but not perfectly) correlated 13.1% at the highest end of the scale (above $4000 gross per (r50.80,p,0.05).

month). The high concentration of low-income respondents

suggests that many respondents are either students or very

Measures

young, which is consistent with the mean age (30.3) of theThe three scales for need satisfaction were introduced by an sampled individuals. Finally, deep-sea diving was the most

identical question. “Different people have different motives for popular (28 individuals), followed by gliding (20), rock and

being active in any given sport (such as soccer, swimming, or mountain climbing (12), and skydiving (8).

jogging). Think about a risky sport that you are involved in and indicate your agreement or disagreement with each of the

Response Rate

following statements. If you strongly disagree, you may mark Practitioners were contacted personally or by phone. Ques- a ‘1’ or ‘2’; if you strongly agree, you may mark a ‘6’ or ‘7’.” tionnaires were handed personally or mailed to practitioners

SATISFACTION OF THE NEED FOR EFFICACY. Need for efficacy who indicated that they did not object to participation in the

was defined as a desire to develop technical skills for personal survey. In all, 47 questionnaires were handed out, all of which

satisfaction and group status. In line with this definition, the were returned. Of the 60 mailed questionnaires, one was

potential of the risky sport to satisfy an individual’s need for undeliverable, whereas 25 were returned for an effective mail

efficacy was operationalized based on three 7-point Likert response rate of 42.4%. Total response rate was 72 of 106

items. These include becoming a better person due to becom-(67.9%). Other studies of risky sports used similar or smaller

ing an expert in the sport, being appreciated by peers because samples. Cronin (1991) used 20 mountain climbers and

Hym-of improving skills in the sport, and gaining satisfaction baugh and Garrett (1974) used 21 skydivers. Kerr (1991)

lowera(0.53) than advocated by Nunnally (1967), an issue of income and seasonality. Some sports may be more costly than others. Skydiving, for example, necessitates a flight, discussed further in the “Limitations” section.

Earlier, we suggested that satisfaction of the need for effi- whereas other sports require lower access costs. By standard-ization, these potential effects are removed. The second depen-cacy is related to the motive of satisfying communitas-related

needs in the drama form (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh, 1993), dent variable is the probability of entering other risky sports in the future, operationalized as the average future probability the danger-neutralization and peer-identification explanations

(Brannigan and McDougall, 1983), and the extraordinary ex- of joining new risky sports. For each non-practiced risky sport, respondents were asked to indicate on 7-point scales (very perience model (Arnould and Price, 1993). Thus, it was

ex-pected that the scale for efficacy will be related moderately and probably not to very probably yes) the probability of joining in the future. We preferred these measures to percentage positively to the frequency at which the sport and associated

experiences are discussed with fellow practitioners, a related probabilities, which were also included in the questionnaire, because of their lower item non-response. However, the corre-measure from the data set. The scale and item were related

moderately and positively (r50.41,p,0.05), indicative of lation between the 7-point scale and the percentage-based scale is high (r50.71,p,0.05) suggesting acceptable relia-the validity of relia-the scale.

bility. SATISFACTION OF THE NEED FOR IDENTITY CONSTRUCTION.

Iden-Given the mostly similar structures of explanatory con-tity construction was defined in terms of the existence of a

structs for the two dependent variables, it was expected that well-defined context for personal change, including the means

both will be related to the measures of talking about the for organizing the new identity. Therefore, the potential of

experiences with friends in and out of the club discussed the risky sport to satisfy a need for identity construction was

above; and that these correlations would be positive and mod-operationalized based on four 7-point Likert items. The items

erate. This indeed was the case. The two correlations for were: the sport having changed one’s life perspective; being

averaged frequency were both positive and significant (r5

able to measure one’s improvement in the sport helping

de-0.40; 0.30,p,0.05). The two for future probability are also velop skills; becoming a better person since joining the sport;

positive and significant (r 5 0.20; 0.21, p , 0.05). This and not having changed much since joining (reversed). The

pattern of correlations strengthens the argument for validity scale’sa (0.65) is close to the level advocated by Nunnally

of the two dependent variables. (1967).

Identity construction should be related to sharing of one’s

experiences within and outside of the club. To assess the

Analysis and Results

scale’s validity, its correlation with four related items designedStatistical Technique

to measure the frequency at which the sport and associated

Analysis of the findings began with an examination of the inter-experiences are discussed with fellow practitioners, with

fam-construct correlation coefficients. Then, a structural equations’ ily, with non-club friends, and in general was examined.

Mod-model, specifically LISREL 8 with maximum likelihood esti-erate and positive correlations were expected, which indeed

mation, was used to test the hypotheses. This methodology was the case as all four correlations were positive, moderate,

allowed the simultaneous estimation of a series of interdepen-and significant (0.39< r<0.41,p,0.05).

dent relationships, incorporated measurement error between SATISFACTION OF THE NEED FOR CAMARADERIE. The potential latent and observed variables, and allowed for the assessment of the risky sport to satisfy a need for camaraderie was assessed of overall model fit. Model constructs were represented by by three 7-point Likert items. The items were: having close single indicators using averaged scales (for efficacy, identity relationships with fellow practitioners, practitioners forming construction, and camaraderie) and direct measures (for age a close group, and having a pleasant and important relation- and experience). The use of single indicators was preferred, ship with fellow practitioners. The scale showed acceptable given the complex structure of the hypothesized relationships, reliability (a 50.85). the large number of required estimates for the specified model, On the basis of the need to interact with fellow practitioners and the small sample size (Price, Arnould, and Tierney, 1995). to satisfy the need for camaraderie, we anticipated a positive

and moderate relationship between camaraderie and an item

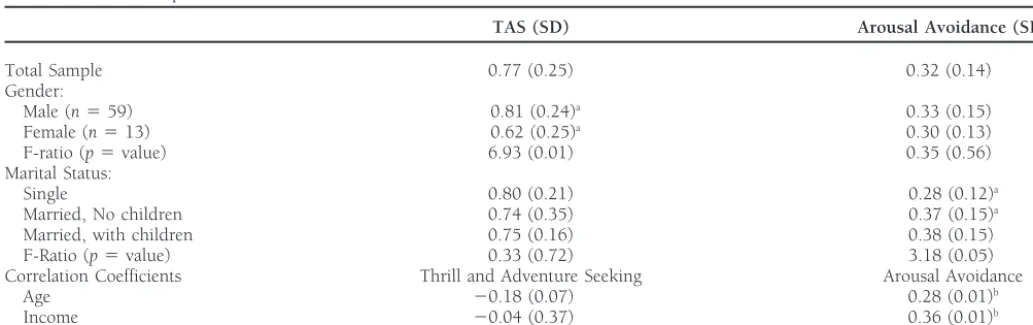

Within-Sample Differences on Sensation

measuring frequency of discussing the sport with club mem-Seeking and Telic Dominance

bers. This indeed was the case (r50.61,p,0.05),

substanti-As expected, the sample means for the scales that have been ating the validity of the scale.

found to differentiate risky sport practitioners from others in previous research (total Sensation Seeking Scale [SSS] and DEPENDENT MEASURES. Two measures were used. The first

was a mean standardized monthly frequency of engagement Thrill and Adventure Seeking [TAS]) were high in our sample: 0.77 (TAS) and 0.56 (total SSS). These values are similar to in risky sports (some individuals indicated more than one

Table 2. Within-Sample Mean Differences

TAS (SD) Arousal Avoidance (SD)

Total Sample 0.77 (0.25) 0.32 (0.14)

Gender:

Male (n559) 0.81 (0.24)a 0.33 (0.15)

Female (n513) 0.62 (0.25)a 0.30 (0.13)

F-ratio (p5value) 6.93 (0.01) 0.35 (0.56)

Marital Status:

Single 0.80 (0.21) 0.28 (0.12)a

Married, No children 0.74 (0.35) 0.37 (0.15)a

Married, with children 0.75 (0.16) 0.38 (0.15)

F-Ratio (p5value) 0.33 (0.72) 3.18 (0.05)

Correlation Coefficients Thrill and Adventure Seeking Arousal Avoidance

Age 20.18 (0.07) 0.28 (0.01)b

Income 20.04 (0.37) 0.36 (0.01)b

aThe two sub-groups differ atp,0.05.

bSignificant r (p,0.05).

(1991)]. The mean score for Arousal Avoidance—the Telic mean future probability of engagement. Notably, the model chi-squared (15.92, 9 degrees of freedom, n 5 72) is not Dominance sub-scale reported to differentiate risky sport

prac-titioners from others—was low in our sample (0.32). This is significant (p,.07). Additionally, the chi-squared to degrees of freedom ratio improved to 1.77. Other fit statistics remained similar to the means reported by Kerr (1991): mean5 0.32

for surfers and motor-cyclists; mean5 0.35 for gliders. substantively the same (normed fit index50.93, non-normed fit index50.92, and standardized root mean squared residu-Given the important role of TAS and AA in explaining risky

sport consumption, we assessed the differences on these scales als50.09) and also suggest acceptable fit. Notably, none of on the basis of gender, family status, age, and income. ANOVA the substantive results changed in the trimmed model. These was used for gender and family status and correlations were statistics show that the data do not deviate from the re-speci-computed for age and income. The results were useful in fied model. We examined the modification indexes for possi-generating managerial implications (Table 2). Males have ble changes to the model. None could be justified theoretically. higher scores (0.81) than females (0.62) on TAS. This is the Additionally, re-specifying the model to account for modifica-only significant demographic correlate of TAS. Singles report tion indexes carries the risk of maximizing the fit for the lower (0.28) AA than married (0.37) individuals. Lower scores idiosyncrasies of our data. Therefore, only the original and on AA are also associated with younger, less affluent individu- trimmed models are discussed below.

als. These demographic differences are discussed in the “Impli- H1 posited that the relationship between the perceived cations” section. satisfaction of identity construction needs in a risky sport and both the frequency of engagement in it and future probability

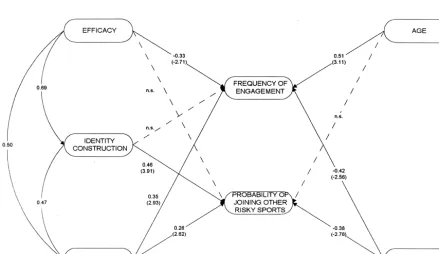

Tests of Research Hypotheses

of engaging in other risky sports in positive. H1 was partially supported. Identity construction was unrelated to the fre-Table 3 provides the means and correlation coefficients for thequency of practice of the sport (b 50.08,t50.57). However, study constructs. The correlation matrix was used to provide

the relationship is positive and significant for future probabil-additional insights to the LISREL analysis (see the “Discussion”

ity of engagement (b 50.46,t53.91 in the original and the section). The results of the LISREL maximum likelihood

esti-trimmed model). In other words, the higher the individual’s mation are shown in Table 4 (for the original and the

re-perceived satisfaction of identity construction needs in one specified model, discussed below) and Figure 1 (for the

origi-risky sport, the higher the probability that the same individual nal model). With the correlation matrix used as input, the

will engage in other risky sports in the future. model appears to fit the data well. The model chi-squared

The perceived satisfaction of efficacy needs in a risky sport (14.75, 7 degrees of freedom, n 5 72) is significant (p ,

was expected to be related positively to both the frequency 0.04). Notably, the use of chi-squared has been questioned

of engagement in it and future probability of engaging in (Loehlin, 1987). Based on Loehlin (1987), we assessed other

other risky sports (H2). The relation was insignificant in the fit statistics. The value for chi-squared/degrees of freedom

frequency model (b 5 0.07, t5 0.46) and significant (but (2.11), the normed fit index (0.93), non-normed fit index

opposite expectations) in the future model (b 5 20.33,t5

(0.89), and standardized root mean squared residuals (0.08)

22.71 in both models). Thus, H2 was disconfirmed. suggest acceptable fit.

The relationship between the perceived satisfaction of ca-We also tested a trimmed model by eliminating the

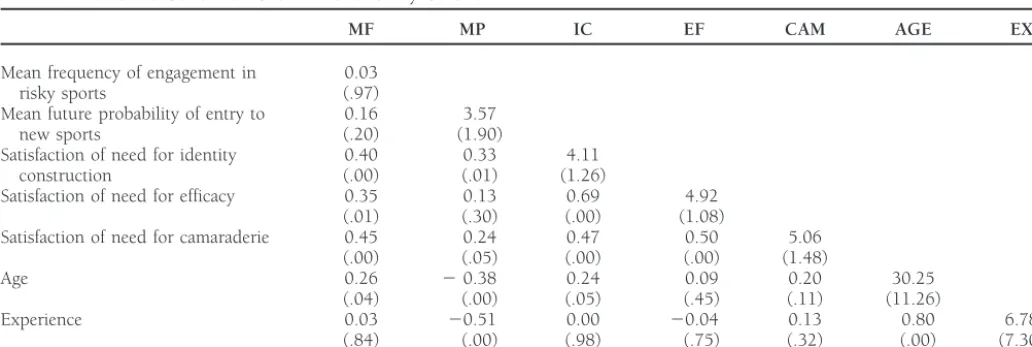

Table 3. Means and Correlation Coefficients for Study Constructsa,b

MF MP IC EF CAM AGE EX

Mean frequency of engagement in 0.03

risky sports (.97)

Mean future probability of entry to 0.16 3.57

new sports (.20) (1.90)

Satisfaction of need for identity 0.40 0.33 4.11

construction (.00) (.01) (1.26)

Satisfaction of need for efficacy 0.35 0.13 0.69 4.92 (.01) (.30) (.00) (1.08)

Satisfaction of need for camaraderie 0.45 0.24 0.47 0.50 5.06 (.00) (.05) (.00) (.00) (1.48)

Age 0.26 20.38 0.24 0.09 0.20 30.25

(.04) (.00) (.05) (.45) (.11) (11.26)

Experience 0.03 20.51 0.00 20.04 0.13 0.80 6.78

(.84) (.00) (.98) (.75) (.32) (.00) (7.30)

aMeans (standard deviations) are on the diagonal; correlation coefficients are off the diagonal (p-values in parentheses).

bAll correlatioins above 0.23 are significant (p,0.05; two-way tests).

engagement in it and future probability of engaging in other measure one’s improvement (efficacy) was important to many respondents. The importance of challenge, thrill, and adven-risky sports was expected to be positive (H3). The model

substantiates this hypothesis. Both coefficients are positive ture was also evident, as was the satisfying group experience during practice (camaraderie). In sum, the need for efficacy, and significant (bfrequency50.35,t52.93,bfuture50.26,t5

2.62 in the original model;bfrequency50.41,t54.10,bfuture5 identity construction, and camaraderie were all used in

re-sponse to the open-ended question. 0.26,t52.62 in the trimmed model).

H4 hypothesized that experience in a risky sport would be positively related to the frequency of engagement in it (H4a)

Discussion

and negatively related to the future probability of engaging inother risky sports (H4b). Experience was negatively related We expected the potential of a risky sport to satisfy identity to the frequency of practicing the sport (b 5 20.42, t 5 construction needs to have a positive effect within two time 22.56 in the original model; b 5 20.48, t 5 22.88 in frames. First, it was expected to affect present behavior, re-the trimmed model)—disconfirming H4a—and to re-the future sulting in a higher frequency of practicing the sport. Second, engagement in new risky sports (b 5 20.38,t5 22.76 in it was expected to affect future behavioral intentions through both models)—confirming H4b. its hypothesized relationship with the probability of engaging No hypothesis was advanced for the influence of age on in other risky sports. The latter relationship was substantiated either of the dependent variables. Interestingly, age was a by the data. The potential of one risky sport to aid in identity positive and significant predictor of frequency (b 50.51,t5 construction carries through to other, non-practiced risky 3.11 in the original model;b 50.57,t53.43 in the trimmed sports. This implies that respondents view new risky sports model), but an insignificant predictor of future probability of as providing similar contexts in which they can evolve and entering new sports (b 5 20.19,t5 21.40 in both models). their identity develop (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh, 1993). The The questionnaire included an open-ended question that importance of identity construction may well depend on Ar-asked respondents to explain their choice and practice of a nould and Price’s (1993) extension and renewal of self. In other risky sport. In all, 47 respondents of the total sample of 72 words, entering into new risky sports provides an opportunity provided between one and six motives. The distribution of to move from self-extension to self-renewal within the novel

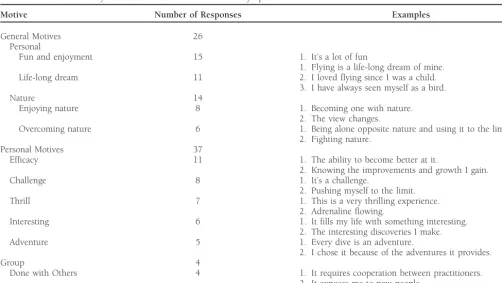

sport. responses is shown in Table 5. The two general and generic

motives were the most popular. Fifteen practitioners reported Interestingly, identity construction potential did not have a significant effect on the frequency at which individuals prac-fun as a major motive and 11 reported that it has been a

life-long dream. Nature also played a role in motivating prac- tice their chosen sport. As can be seen in Table 3, the correla-tion between the need for identity construccorrela-tion and the fre-titioners. However, it has opposite effects on two-sub-groups

of respondents. Some respondents emphasize the need to quency of practice is positive and significant (r50.40,p,

0.01). However, this relationship does not carry through to enjoy nature and become one with it. Others point out their

attempt to overcome and conquer nature by their acts. the LISREL analysis. It may be that the path estimates were reduced due to inter-scale correlations. If this is the case, the The three themes included in this research are also present

Table 4. Frequency of Practice and Future Probability of Entering New Sports: LISREL Maximum Likelihood, Standardized Estimates (t-values in Paranthesis)

Mean Frequency of Mean Future Probability Independent Variables Engagement in Risky Sportsa Of Entry to New Sports

Satisfaction of need for identity constructionb 0.08 (0.57) 0.46 (3.91)

Satisfaction of need for efficacyc 0.07 (0.46) 20.33 (22.71)

Satisfaction of need for camaraderie 0.35; 0.41 (2.93; 4.10) 0.26 (2.62)

Age 0.51; 0.57 (3.11; 3.43) 20.19 (21.40)

Experience 20.42;20.48 (22.56;22.88) 20.38 (22.76)

Squared multiple correlations for structural equationsc 0.29 0.50

aOriginal model appears first, followed by the trimmed model.

bThese paths were excluded in the trimmed model.

cOriginal model’s

v2(14.75, 7 degrees of freedom) is significant (p,0.04). Its ratio ofv2/degrees of freedom is 2.11. The normed fit index is 0.93, non-normed fit index is 0.89,

and the standardized root mean squared residuals equal 0.08. The trimmed model’sv2(15.92, 9 degrees of freedom) is not significant (p,0.07). The ratio ofv2to degrees of

freedom is 1.77. Normed fit index50.93, non-normed fit index50.92, and standardized root mean squared residuals50.09.

the association between the two variables in support of the identity construction does not affect practice frequency. Hav-ing achieved a level of competence in a sport may result first research hypothesis.

Alternatively, the potential of practice to contribute to iden- in sufficient satisfaction, thus reducing the need for further improvement and practice. The distance between the ideal tity construction may be subject to a ceiling effect. Once

individuals attain given levels of expertise and satisfy their and real selves (Rogers, 1980) when beginning a new sport may be much larger than at latter stages. Initially, the novice need for identity construction, the sport may lose its luster.

If a ceiling effect is operating, practice may be limited to levels knows very little, especially when compared to experts and professionals. As one becomes an expert, the distance between designed to maintain one’s standard of expertise (similar to a

minimal number of flights required of amateur pilots). This real and ideal selves is reduced, resulting in a lower motivation for action (Rogers, 1970).

explanation also agrees with the significant effect for future

probability discussed above. Engaging in new sports enables The need for efficacy was insignificant in the present fre-quency model and, contrary to expectations, was negatively consumers to break the barrier within the original sport.

Couched in the terminology of self-actualization (Bandura, related to the future probability of engaging in new sports. Notably, the bivariate correlation coefficients differed. The 1965; Rogers, 1970), our findings show that the need for

Table 5. Motives for Entry and Continuous Involvement in Risky Sports

Motive Number of Responses Examples

General Motives 26

Personal

Fun and enjoyment 15 1. It’s a lot of fun

1. Flying is a life-long dream of mine. Life-long dream 11 2. I loved flying since I was a child.

3. I have always seen myself as a bird.

Nature 14

Enjoying nature 8 1. Becoming one with nature.

2. The view changes.

Overcoming nature 6 1. Being alone opposite nature and using it to the limit. 2. Fighting nature.

Personal Motives 37

Efficacy 11 1. The ability to become better at it.

2. Knowing the improvements and growth I gain.

Challenge 8 1. It’s a challenge.

2. Pushing myself to the limit.

Thrill 7 1. This is a very thrilling experience.

2. Adrenaline flowing.

Interesting 6 1. It fills my life with something interesting. 2. The interesting discoveries I make.

Adventure 5 1. Every dive is an adventure.

2. I chose it because of the adventures it provides.

Group 4

Done with Others 4 1. It requires cooperation between practitioners. 2. It exposes me to new people.

need for efficacy was positively and significantly related to sports, compare the skills in river rafting (Arnould and Price, 1993; Price, Arnould, and Tierney, 1995) and those in sky-the frequency of practice (r 5 0.35, p, 0.01), but not to

the future probability of engagement in additional sports (r5 diving (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh, 1993). Furthermore, because skills are not transferable, having mastered one sport hinders 0.13,p , 0.30). However, we believe that in this case the

LISREL analysis provides a better measure for the direction the probability that one will initiate a new sport and start the apprentice phase all over again.

and strength of the two relationships. It is well documented

that structural equation modeling has advantages when as- Camaraderie positively affected both present frequency and future probability of engagement in risky sports, as hypothe-sessing the interdependent relationships between multiple

de-pendent and indede-pendent variables. This may well be a case sized. The significant correlation coefficients in Table 3 carried through to the LISREL analysis. The strong effect of commu-in pocommu-int.

Another possible explanation for the failure of efficacy to nitas on skydiving (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh, 1993) and on satisfaction with river rafting experiences (Arnould and Price, have an effect on how frequently individuals practice risky

sports is similar to the one discussed above for identity con- 1993; Price, Arnould, and Tierney, 1995) carries through to this study’s dependent variables. Stated differently, not only struction needs, namely the existence of a ceiling effect. There

may exist some level of expertise beyond which frequent dives, does the potential of a risky sport affect satisfaction with a given instance of consumption of the sport (river rafting) or skydives, or climbs fail to contribute sufficiently to encourage

further practice (Bandura, 1965). Similar to the need for iden- continued involvement (skydiving), it also results in more frequent participation and a higher probability of joining other tity construction, the perceived distance between the original

ideal self and the evolving real self may result in a lower drive risky sports.

Camaraderie was the only significant explanatory variable for improvement (Rogers, 1970).

Efficacy is negatively related to the probability of engaging for frequency of engagement. We suggested earlier that iden-tity construction and efficacy are subject to a ceiling effect. in new risky sports. Efficacy is closely related to competence

in a given risky sport. Celsi, Rose, and Leigh, (1993), for No such effect is evident for the need for camaraderie. This finding is consistent with past descriptions of communitas as example, link personal satisfaction and enhanced social

stand-ing to the development of expertise in skydivstand-ing. There is a higher order, transcendent motive (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh, 1993), that remains important, even for the experienced and no reason to expect skydiving-related skills to enhance one’s

butI still can’t think of anything better to do than to come out and stronger needs for new selves may have balanced out. This would explain the LISREL-based findings.

here with my friends and make a skydive” [Celsi, Rose, and

Leigh (1993), p. 12; emphasis added]. Another experienced We also note here that experience and age were highly correlated and that our sample is composed primarily of jumper commented: “Jumpers have a special kind of bond . . .

What people do and how much money they make just doesn’t younger individuals. Future research with a broader cross-section of ages may find that experience behaves in a curvelin-matter. There’s just this closeness here” [Celsi, Rose, and Leigh

(1993), p. 12; emphasis added]. ear fashion. Given these multiple competing explanations, further research is needed on the impact of age on risky sport As expected, experience is related negatively to the future

probability of joining new sports, as evidenced by a significant consumption. correlation coefficient and a significant path in the LISREL

analysis. Non-transferability of skills developed in one sport

Managerial Implications

results in a reluctance to consider additional sports. Compare Previous hedonic research has focused on thick description Michael Jordan’s mediocre baseball performance to his success and has largely ignored managerial implications. Our discus-in basketball, for an example of the difficulty of movdiscus-ing from sion of managerial implications is divided into four parts. one sport to another. Although efficacy and identity construc- First, we discuss the implications for maintaining membership tion do not affect the frequency of practice in a given sport, in a given sport and increasing practice frequency. Then, we a strong need for efficacy inhibits entry into other sports. In discuss the findings as they relate to attracting individuals contrast, identity construction is positively related to entering from one risky sport to another and encouraging multi-sport new sports. Once individuals have satisfied their need for participation. Finally, we discuss the responses to an open-identity construction in one sport, they seek additional or ended question about reasons for practicing the sport and renewed extensions of self in new sports. This behavior is suggest possible advertising themes and messages.

consistent with a need for unique and arousing experiences,

MAINTAINING MEMBERSHIP AND INCREASED USAGE. Individu-which is typical of sensation-seeking individuals who practice

als who practice more often are sometimes older and less risky sports.

experienced practitioners. These two findings suggest that It can be argued that experience and the need for efficacy

older members of the club are prime targets for frequency-should be related. In other words, as individuals gain

experi-enhancing marketing strategies. Prices may be lowered to ence they become more proficient in their chosen sport. Such

facilitate extended membership for members above a certain a process should lead to a reduction of the impact of the need

age. Alternatively, homogeneous groups of older practitioners for efficacy. However, this was not the case in our study.

may be organized to facilitate camaraderie needs within a The two constructs’ correlation coefficient was not significant.

more homogeneous age group. Such groups will benefit from Additionally, we ran another LISREL model allowing the two

the findings that similarities attract (e.g., Newcomb, 1960, to be correlated. This model resulted in lower levels of fit

1961). Given that older members also tend to be arousal statistics and the path between the two constructs was not

and, marginally, thrill and adventure avoiding (Table 2), the significant. In other words, the need for efficacy is not

weak-message to these individuals should stress camaraderie. How-ened by experience. It may be that the emphasis shifts (e.g.,

ever, age-homogeneous grouping is a risky strategy because higher peaks, longer free falls, etc.), but the impact remains

older individuals serve an important purpose in socializing strong.

newcomers. This purpose also serves to enhance the efficacy Age was posited to have conflicting effects on frequency

and communitas aspects of practicing high-risk sports. Thus, and future probability. Interestingly, older people tend to

the forming of homogeneous age groups should not carry practice the sport more often (both the correlation coefficient

through to all club activities. Ample opportunity should be and the path estimate were positive and significant). The

physi-provided for heterogeneous groups to interact as well. cal costs of participation for older people may be higher;

there-Less experienced individuals provide an important source fore, only those individuals that are really committed to a

spe-of future revenue. Marketing managers can create member-cific sport participate in it as they get older. The need to create

ship-enhancing strategies for this group. One option is to new selves may also be stronger among older individuals.

create social events that cater to the less experienced members, Age did not affect the future probability of entering new

risky sports. The effect was negative, but failed to reach signifi- regardless of age. Additionally, more experienced members should be encouraged to mentor less experienced ones through cance. However, the correlation coefficient was negative and

significant (Table 3). Our path estimates may have been re- social events and discounts for mixed experience participation. Homogeneous experience groups can also be organized, but duced because of the nature of the data. In other words,

the bivariate correlation coefficient provides support to the it is still important to encourage camaraderie and modeling across experience levels. Such activities should carry through stronger negative impact of the physical fitness argument over

groups should be balanced with mixed audience activities to in advertising copy. This may include slogans such as “Isn’t it time to realize your life-long dream?” Nature also played a allow socialization.

Camaraderie has a positive impact on practice frequency significant role in practitioners’ motives. Respondents empha-sized a need to enjoy nature and a desire to overcome and and risky sport clubs should provide activities that enhance

it both within and across experience levels. The more frequent conquer it. Therefore, a balance needs to be maintained be-tween these facets. One possibility is to separate the consump-and successful the meetings of older or less experienced

mem-bers (in addition to mixed functions) the more frequent the tion experience. One can enjoy nature during the slower por-tions of a river yet overcome and conquer the rapids. practice due to the potential to satisfy camaraderie needs.

Camaraderie in an important motive for risky sport partici-ATTRACTING INDIVIDUALS FROM ONE RISKY SPORT TO ANOTHER.

pation. Individuals pointed out the satisfying group experience Individuals who are engaged in one risky sport are a target during practice and their desire for challenge, thrill, and ad-segment for other sports. Less experienced members are more venture. Challenge, thrill, and adventure can be seen as spe-likely to intend to engage in additional risky sports in the cific manifestations of identity construction, which is posi-future. Thus, members just beginning the ascent to expertise tively related to the probability of engaging in new risky sports. are prime candidates for managers in other clubs. Stated

differ-These themes should be emphasized when targeting people ently, young and inexperienced practitioners of one risky sport

who practice another risky sport. have already made the commitment to the risky sport they

The negative correlation between efficacy and frequency selected—they have gone over the threshold once. As they

of practice provides an interesting problem for managers: have less expertise and investment in a specific sport and have

how do you motivate experienced individuals to continue to not yet satisfied the various needs that drove them to join the

participate after they have reached a given level of compe-initial sport, an effort could be made to attract them to switch

tence? Many individuals tend to “collect” achievements in sports. For example, given the low income of many younger

a risky sport. Belk [(1995), p. 67; emphasis added] noted: practitioners, special prices may be offered for

cross-member-“Collecting is the process of actively, selectively, and passion-ship. Emphasis may also be placed on age-cohort positioning.

ately acquiring and possessing things removed from ordinary Since younger practitioners tend to be arousal and thrill and use and perceived as part of a set of non-identical objects or adventure seekers, communications with younger members experiences.” The most important benefit of collecting is the should stress these benefits. This is especially important for feeling of mastery, competence, or success (Belk, 1995). These single members whose arousal avoidance scores were lower benefits may provide a means of maintaining the participatory than those for married individuals. motivation of experienced members. Additionally, the benefit Identity construction and camaraderie were found to affect of the specialized vocabulary and knowledge used by collec-potential participation in additional sports. Thus, advertising

tors provide additional motivation for collecting (Belk, 1995). and promotion should reflect this potential. Messages should

In short, collecting high-risk sport achievement can be viewed emphasize the opportunity to enhance camaraderie and build

as any other collecting-type phenomena. Viewed in this light, new selves. Visuals (photos, posters, videos, etc.) should

incor-individuals may count the number of peaks climbed in the porate group settings and convey a feeling of camaraderie.

Canadian Rockies. This suggests another fruitful theme for Given its negative impact on switching behavior, the need for

advertising campaigns. A firm catering to divers in the Middle efficacy should be de-emphasized. Managers are advised to

East could emphasize a message such as “Dive all the major de-emphasize the efficacy enhancing potential of the new

sites along the eastern Sinai desert.” Such themes would en-sport, so as not to remind targeted individuals of the

invest-courage participation among experienced practitioners. ment they have made in developing expertise in another sport.

Limitations and Directions for

MULTI-SPORT PACKAGES. Marketing multi-sport packages may

be used as well. While each risky sport competes for a share

Future Research

of the overall market, multi-sport participation may increase Two of the three needs’ satisfying scales resulted in medium-the size of medium-the market. Thus, marketers of a high-risk sport strength reliability coefficients. More work is needed to expand may consider diversification or tie-ins with other sports. Once and refine the measures employed, especially for the set of the diversification is carried out, such firms may develop items to measure the need for efficacy. Additionally, we mea-multi-sport advertising themes. For example, a firm catering sure the probability of joining other risky sport activities. to river rafting and mountain climbing may run a campaign Measuring actual behavior (joining a second risky sport) may such as: “Take our river rafting trip from ‘A’ to ‘B’ and then yield additional insights. Longitudinal research designs are

climb atop mountain ‘C’.” necessary for this purpose.

Our study was conducted in Israel and included

prac-Advertising Themes

titioners of four risky sports. Thus, the issue of generalizability to other cultures and other types of risky sports is important. Joining and sticking with a risky sport is a realization of ain the context of industrialized nations and cultures that have force (operationalized here as justifying the communion with nature). They also see nature as playground—their third been studied to date. Sample means on sub-scales of the

theme, which emerged in our research as well. However, both Sensation Seeking scale and the Telic Dominance scale were

Simmons’ (1993) and Arnould, Price and Tierney’s (1998a, comparable to means from other countries (e.g., Germany)

1998b) analyses of nature as a social construction includes a and other sports (e.g., surfing and motor-cycling). Apparently,

fourth theme of nature as a reserve. For example, Simmons engagement in risky sports transcends national cultures, at

[(1993), p. 16] sees nature as a reserve of resources, used to least for the developed nations where catharsis and escape

potential depletion by humans (p. 36). Most high-risk sports from bureaucratic roles provides a context for risky sport

do not use these resources, enhancing their potential value consumption (Celsi, Rose, and Leigh, 1992). However, further

to practitioners. research is needed in multiple contexts. First, there is a need to

Future research should measure the importance of con-study high-risk sport consumption in less developed countries.

quering and communing with nature, as well as the impor-Second, it may be necessary to recognize that even within a

tance of nature as a reserve of playground. Nature may repre-dominant, national culture, there may be sub-cultures that differ

sent as additional motivation for risky sport consumption. in high-risk sport consumption. For example, the very orthodox

Future research should determine the extent to which nature Jewish sub-population may also be less inclined to engage in

can be incorporated into our model, particularly the extent to high-risk sports. Additionally, as indicated in our qualitative

which nature-related motivations are sport specific or operate interviews with practitioners, what sport is perceived as risky

across a range of sports. Future research is also needed to is a subjective evaluation that may vary across cultures and

sub-identify the potential impact of these attributes for sub-seg-cultures. Thus, there is a need for additional research to more

ments of the population. finely identify the boundaries under which the trans-national

Future research could also examine the influence of the and trans-sport applications of our model hold.

variables used in this study to other facets of consumer risk-Our sample included younger, male-dominant individuals.

taking behavior. For example, drug abuse and excessive con-We believe that this bias reflects the demographic composition

sumption of alcohol may also depend on the (albeit misguided) of practitioners in Israel. However, the generalizability of the

need for camaraderie and identity construction (Burns et al., findings to older, more balanced gender samples is open to

1993; Severson et al., 1993). question. There is a need for further studies with more

hetero-Finally, our model accounts for frequency of engagement geneous samples in Israel and in other nations.

in risky sports at the present and the probability of joining Our study examined individuals, who are already engaged

other risky sports in the future. It will be interesting to study in risky sports, which may have restricted our range on some

other outcome measures. For example, does the same set of variables. Practitioners of risky sports may have a higher need

explanatory variables used here account for commitment to for thrill, adventure, efficacy, identity construction, and

cama-the sport? Are cama-the relationships similar for measures such as raderie than the general population. Thus, our findings may

investing in equipment, subscribing to professional journals, understate the relationship of some variables in our model.

and practicing the sport in other countries? Alternatively, does It is also necessary to study pre-joining behavior among

the same set of explanatory variables account in a similar the general population. Celsi, Rose, and Leigh (1993), Arnould

fashion for the probability of future commitment to the sport? and Price (1993), and Brannigan and McDougall (1983)

sug-gest that engaging in risky sports may depend initially on

The authors thank Miss Dorit Gack, Dalia Hagiz, and Rinat Rabinovich for factors such as liking for thrills, adventures, social enhancing

their help in data collection and Professor David Boush for comments made activities, and curiosity satisfying experiences. Future research

on an earlier draft. We also thank the associate editor and two anonymous could assess the impact of the potential of risky sports to deliver

reviewers for many helpful comments on an earlier draft. This research was satisfaction of these needs on the future probability to join. supported in part by the Technion V.P.R. Fund.

Importantly, responses to the open-ended question re-vealed the importance of two constructions of nature

(con-References

quering and communing). Future research could focus on the

Apter, Michael J: Some Data Inconsistent with the Optimal Arousal

role of nature in risky sport consumption. Simmons [(1993),

Theory of Motivation.Perceptual and Motor Skills43 (1976): 1209–

pp. 12–13] perceives nature as a multi-faceted social

construc-1210.

tion. “The construction of the world of mankind” led mankind

Apter, Michael J.:The Experience of Motivation, London, UK: Academic

to try and conquer nature; however, there exits a concept of

Press, London, UK. 1982.

a “Golden Age”, in which “harmony between humans and

Arnould, Eric J., and Price, Linda L.: River Magic: Extraordinary

nature” is said to exist. Simmons’ (1993) approach is some- Experience and the Extended Service Encounter.Journal of Con-what similar to Arnould, Price and Tierney’s (1998a, 1998b) sumer Research20 (1) (1993): 24–45.

conceptualization of nature. They also recognize nature as a Arnould, Eric J., Price, Linda L., and Tierney, Patrick: The Wilderness determinant of American character (operationalized in our Servicecape: An Ironic Commercial Landscape, in Servicecapes:

The Concept of Place in Contemporary Marketplaces, John Sherry,