www.elsevier.comrlocaterapplanim

A comparative assessment of potential conditioned

taste aversion agents for vertebrate management

Elaine L. Gill

a,), Anne Whiterow

b, David P. Cowan

aa

Central Science Laboratory, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Sand Hutton, York YO4 1LZ, UK

b

Central Science Laboratory, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Badger Research Station, Tinkley Lane, Nympsfield, Stonehouse, Gloucester GL10 3UJ, UK

Accepted 25 November 1999

Abstract

Ž .

A conditioned taste aversion CTA is acquired through an association between the taste of a food and a feeling of illness experienced after ingestion. It can be induced deliberately by the addition of an undetectable illness-inducing chemical to food. Harnessing the CTA response could provide humane and effective means of controlling vertebrate pest problems. For field use, the ideal illness-inducing chemical should induce a robust CTA after a single oral dose, at which it must cause neither chronic illness nor persistent detrimental effects in the target or any non-target species at risk of exposure; it must also be undetectable and physically stable in the bait substrate.

At present, no compound that satisfactorily meets all of these criteria has been identified. 17a

ethinyl oestradiol meets most but, as a synthetic oestrogenic hormone, it can affect reproductive

Ž .

processes. The ability of two potentially safe compounds, cinnamamide 160 mgrkg and

Ž .

thiabendazole 100 and 200 mgrkg to generate a CTA in the laboratory rat Rattus norÕegicus to

Ž .

a novel food was assessed and compared to that of 17a ethinyl oestradiol 4 mgrkg . All

compounds induced a CTA after a single dose, which lasted for at least two post-treatment tests,

but no CTA was as persistent as that induced by 17aethinyl oestradiol, which lasted in some rats

Ž .

for )11 post-treatment tests 6 months . Thiabendazole at 200 mgrkg induced the next best

CTA, persisting for five post-treatment tests. Cinnamamide and thiabendazole could provide safe

)Corresponding author. Farming and Rural Conservation Agency, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Block C, Government Buildings, 98 Epsom Road, Guildford, Surrey GU1 2LD, UK. Tel.:q 44-1483-404267; fax:q44-1483-403646.

Ž .

E-mail address: [email protected] E.L. Gill .

0168-1591r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Ž .

( ) E.L. Gill et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 67 2000 229–240 230

alternative CTA agents to 17a ethinyl oestradiol for field use; the use of a second dose of these

compounds to improve longevity of the CTA warrants further study. q2000 Elsevier Science

B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Conditioned taste aversion; 17a Ethinyl oestradiol; Cinnamamide; Thiabendazole; Rat; Vertebrate

control

1. Introduction

Ž .

A conditioned taste aversion CTA is acquired through an association between the

Ž .

taste of a food and a feeling of illness experienced after ingestion Garcia et al., 1974 . This association is not under conscious control, and is believed to be made in the area

Ž .

postrema of the brain stem Borison and Wang, 1953; Bernstein et al., 1986 . Once such an association has been made, the consumer will avoid eating food with that taste again,

Ž .

sometimes experiencing nausea on re-encountering it Gustavson et al., 1974, 1976 . This is a natural response that has evolved to prevent poisoning, and exists in many

Ž .

animals including some invertebrates Gustavson, 1977 . CTA can be induced deliber-ately by providing an animal with a food treated with an undetectable malaise-inducing chemical. The chemical must be undetectable for the target individual to form the

Ž .

association between the real taste of the food rather than adulterated food and illness. CTA has the advantage that a single dose can be sufficient to prevent consumption of a

Ž

particular food for many months without having to re-dose the animal Gill et al., in .

prep. . Harnessing the CTA response has the potential to provide a powerful, non-lethal, environmentally sensitive means of reducing problems of predation, crop damage, and nuisance caused by vertebrates.

The nature and dose of the illness-inducing chemical is critical to the success of this technique. For field use, a CTA compound should induce a robust, long-lasting CTA

Ž .

after one or possibly two oral dose. At this effective dose, it must cause neither chronic illness nor persistent detrimental effects in the target or any non-target species at risk of exposure. The formulated compound must also be undetectable, physically stable in the bait substrate, and sufficiently delayed in action to allow the target animal to finish its

Ž .

meal Nicolaus et al., 1989a

A compound which induces a robust CTA and meets most of these criteria is 17a

ethinyl oestradiol, a synthetic oestrogenic hormone. It appears to be undetectable by Ž

mammals e.g., rats Rattus norÕegicus, foxes Vulpes Õulpes, and raccoons Procyon .

lotor when added to baits at a dose of F4 mgrkg body weight, and a single dose can Ž

generate a long-lasting aversion to a given food Nicolaus et al., 1989a,b; Semel and

. Ž

Nicolaus, 1992 . This dose is well below the compound’s oral LD50 in the rat 1200 .

mgrkg but as a synthetic reproductive hormone, the compound has potential to affect Ž

reproductive processes and systems Jean, 1968; Yanagimachi and Sato, 1968; Yasuda .

Many compounds have been assessed for their efficacy in generating CTA for vertebrate control. Most fail because they are either ineffective or unstable when

Ž

administered orally, e.g., apomorphine Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 1979;

. Ž

Conover, 1989 ; are unsafe at the effective dose, e.g., carbachol Nicolaus and Nellis,

. Ž .

1987; Gill et al., in prep. and emetine Conover, 1989 ; or because they are too

Ž .

detectable at levels required to generate an aversion, e.g., lithium chloride Burns, 1980 . Safe and effective alternatives are needed.

Two compounds, cinnamamide and thiabendazole, warrant further study. Cinna-mamide is a synthetic derivative of cinnamic acid, a naturally occurring plant secondary compound. It is repellent to both birds and mammals, acting through its taste and smell

Ž

and through a post-ingestional effect at higher doses e.g., Watkins et al., 1995; Gurney .

et al., 1996; Gill et al., 1997 . When its taste and odour were masked, a single oral dose of 160 mgrkg induced a CTA to sweet water in captive house mice Mus musculus which, under two-choice testing against plain water, lasted throughout a 64-day trial ŽWatkins et al., 1998 . This dose is 10% of the oral LD. 50 for mice 1600 mgŽ rkg and no. long lasting ill effects were noted. Thiabendazole is approved for use as a systemic fungicide and an anthelmintic for mammals. Timber wolves fed a single dose of 55–80 mgrkg thiabendazole avoided some meat-based foods, especially when they had not

Ž .

been food-deprived Zeigler et al., 1983 . New Guinea wild dogs and dingoes fed two Ž

doses of 40–80 mgrkg in lamb meat refused to eat untreated lamb meat Gustavson et .

al., 1983 , and black bears reduced their damage to beehives after consuming beeswax

Ž .

and ‘slum gum’ bait containing 160 mgrkg Polson, 1983 . The doses of thiabendazole Ž used in these experiments are -6% of its lowest documented oral LD50 in rats 3100

. mgrkg .

We compared the ability of cinnamamide, thiabendazole, and 17a ethinyl oestradiol

to induce a CTA to a novel food in the laboratory rat. Novel foods were used because they more readily induce CTAs than do familiar foods that previously have produced no

Ž .

ill effects Revusky and Bedarf, 1967; Wittlin and Brookshire, 1968 .

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Test compounds

Ž .

The test compounds were dissolved cinnamamide and ethinyl oestradiol or

sus-Ž . Ž . Ž .

pended thiabendazole in polyethylene glycol 400 mol wt. and distilled water 1:1 , and administered by a single oral intubation at a volume of 2 mlrkg rat weight. 17a

Ethinyl oestradiol was administered at 4 mgrkg, a dose shown to induce a robust CTA

Ž .

in rats Nicolaus et al., 1989a . Cinnamamide was administered at 160 mgrkg, as used Ž .

with mice by Watkins et al. 1998 , and thiabendazole at 100 mgrkg, a dose midway Ž

between effective doses for bears and canids Gustavson et al., 1983; Polson, 1983; .

Zeigler et al., 1983 . Owing to an inconclusive result obtained with thiabendazole at 100 mgrkg, and considering its wide safety margin, this compound was also tested at 200

Ž .

mgrkg 6.5% of its oral LD50 in the rat . Compounds were tested one at a time. All

Ž .

( ) E.L. Gill et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 67 2000 229–240 232

2.2. Animals

Ž .

Adult Wistar rats Tuck and Son, Battlesbridge, UK of both sexes were individually housed in wire mesh cages with mesh floors containing paper wool bedding and an

Ž

individually labelled food bowl. They were fed ground SDS rat diet Special Diet .

Services, Witham, UK ad libitum, and were neither visually nor aurally isolated. The

Ž .

room was maintained at 21"28C with a 12 h lightrdark cycle 0600r1800 h . Water

was available ad libitum at all times from a drinking bottle on the front of the cage. For each compound and dose, rats were randomly assigned to one of the three

Ž .

groups: ‘Treated’ T group which received a single intubation of the test chemical; Ž .

‘Treatment Control’ TC group which received a single intubation of the PEG and Ž .

water carrier; and ‘Control’ C group which were fed and handled in the same way as the other two groups but were not intubated. Equal numbers of each sex were allocated to each treatment. All rats were tested in the same room and the positioning of rats receiving different treatments was random within the cage racks, thus minimising any effects that social interactions between rats may have on the rats’ responses to their treatments. Rats were weighed before treatment and a dose and intubation volume calculated for each individual. Normal food consumption of each individual was determined by daily measurement of ground SDS for G7 days before treatment. T and

Ž TC rats were used to test only one compound or dose; C rats were re-used once in order

.

to minimise the total number of animals used in these experiments for a different compound or dose, but never with the same novel food.

2.3. NoÕel foods

The following foods were used to ensure novelty of food to all rats in each trial: Ž .

ground cinnamon and crushed digestive biscuit 1:40 was used with 17a ethinyl Ž . oestradiol and thiabendazole 100 mgrkg; and icing sugar and porage oats 1:15 and

Ž .

almond essence 1 drop: 20 g oats and sugar was used with cinnamamide and thiabendazole 200 mgrkg.

2.4. Treatment

Ž .

Rats deprived of food for 16 h overnight were presented with 20 g of a novel food Ž

in their own bowl wiped out with a damp cloth to remove SDS dust and placed in .

Consumption of SDS diet was measured daily to identify any effects of treatment on consumption of normal diet, and to determine when the rats had recovered from treatment.

2.5. Post-treatment testing

Post-treatment testing began when all rats had recovered from any ill-effects of treatment and had resumed their normal consumption of SDS; G7 days were allowed for this. Rats from all groups were food deprived overnight for 16 h and then presented with 20 g of the same ‘novel’ food they received prior to treatment for 30 min. As on treatment day, this food was provided in each rat’s own bowl that had been wiped out with a damp cloth. The time taken for each rat to investigate the bowl and the rat’s activity during the 30-min presentation were recorded. Consumption was measured on removal of the bowl. Bowls were then emptied, washed and dried, and returned to the rats 1 half h later containing a measured amount of SDS. The time taken to investigate the bowl was recorded. Post-treatment testing of all groups was repeated every 7 days

Ž .

for up to 5 weeks post-treatment tests 1–5 or until consumption of novel food did not differ significantly between groups.

In order to allow time to carry out procedures and observations for each treatment,

Ž .

the timing of all procedures pre-treatment, treatment, and post-treatment was staggered by 30 min for each treatment group: for example, C group rats had their SDS taken away at 1630 h the previous day and received their novel food between 0830 and 0900 h; TC group rats’ SDS was removed at 1700 h and they received novel food between 0900 and 0930 h; and T group rats’ SDS was removed at 1730 h and novel food was presented between 0930 and 1000 h.

Minitab for Windows was used for all data analyses. The study was carried out under

Ž .

a UK Home Office license, in accordance with the Animals Scientific Procedures Act, 1986.

3. Results

There was a number of responses common to all compounds. With the exception of thiabendazole at 100 mgrkg, at least 86% of rats ate )1 g of the novel food during its first presentation prior to treatment, and consumption was similar among all treatment

Ž w x .

groups one-way analysis of variance ANOVA : P)0.05, Table 1 ‘Pre-treat’ . For all compounds and dose rates, consumption of ‘novel’ food in post-treatment tests by

Ž . Ž .

control group rats TC and C was similar one-way ANOVA: P)0.05, Table 1 and generally increased over time. Responses specific to the different compounds and doses were as follows.

( )

3.1. 17a Ethinyl oestradiol 4 mgrkg

3.1.1. Treatment

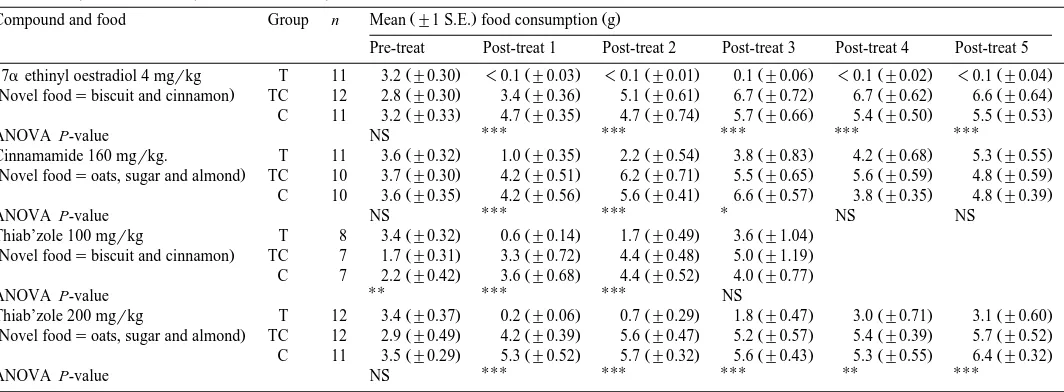

()

Mean consumption of novel foods by treated T , treatment control TC and control C groups of rats before and after treatment with 17a ethinyl oestradiol, cinnamamide, or thiabendazole

NS P)0.05;UPs0.05–0.01;UUPs0.01–0.001;UUUP-0.001.

Ž . Ž .

Compound and food Group n Mean "1 S.E. food consumption g

Pre-treat Post-treat 1 Post-treat 2 Post-treat 3 Post-treat 4 Post-treat 5

rats had investigated after 66 min. At 24–48 h after treatment, T rats showed a marked

Ž .

reduction in consumption of SDS 33–70% daily pre-trial consumption , although none appeared unwell. Consumption returned to normal over the following 6 days and the first post-treatment test was carried out 8 days after treatment.

3.1.2. Post-treatment tests

All rats investigated the novel food in their bowl during the 30 min trial, but Ž consumption varied significantly between groups for all five post-treatment tests

one-.

way ANOVA: P-0.001, Table 1 . Consumption by T rats was negligible in all post-treatment tests, whereas that of TC and C groups was at least that of the treatment day. In the course of the 30 min trial, some T rats dug in the food bowl with their

Ž .

forepaws, some chewed their bedding pica , and most eventually retired to their bedding and either slept or sat inactive. These behaviours were not seen in TC or C rats, most of which ate continuously for much of the 30 min trial. Consumption of SDS diet remained at pre-trial levels between post-treatment tests.

Ž .

Additional post-treatment presentations carried out at ca. 3-week intervals were made with T group rats to determine the time to extinction of the CTA generated by this compound. These demonstrated a gradual attenuation of the aversion over time for most

Ž .

rats, although three continued to eat -1 g after 11 post-treatment tests 6 months ; complete attenuation of the aversion by all individuals occurred after 15 post-treatment

Ž .

tests 11 months . At 14 months after the first treatment, the possibility of regenerating

Ž .

this aversion to the same food through a second intubation of oestradiol 4 mgrkg was

Ž .

investigated in six T rats the other five had either died of old age or been euthanised . In all five post-treatment tests carried out weekly after the second intubation, all six rats ate -0.1 g of food.

( )

3.2. Cinnamamide 160 mgrkg

3.2.1. Treatment

After treatment, no signs of illness were recorded in groups TC and C, but some individuals in group T became listless and excessively sleepy. Although most rats investigated the SDS within an hour of its presentation, one T group individual did not approach for )4 h, and another took )8 h. All individuals appeared well the

Ž .

following day 24 h after treatment , and normal consumption of SDS was resumed by all rats within 3 days. The first post-treatment test was carried out 7 days after treatment.

3.2.2. Post-treatment tests

In all trials, all rats investigated the ‘novel’ food in their bowl. Consumption varied Ž

significantly between groups in the first three trials one-way ANOVA: Ps0.025–0.001, .

Table 1 . In the first trial, consumption by T rats was negligible, although most individuals spent much of the 30 min at their food bowl. During the next two trials, consumption by T rats increased but was still less than that of groups TC and C. By

Ž

trials 4 and 5 there was no significant difference between groups one-way ANOVA: .

( ) E.L. Gill et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 67 2000 229–240 236

3.3. Thiabendazole, 100 mgrkg

3.3.1. Treatment

Ž

Consumption of novel food before treatment differed between groups one-way .

ANOVA: Ps0.009, Table 1 ‘pre-treat’ , with most being eaten by T rats and least by TC rats. This may be related to the generally low consumption of novel food by these

Ž .

rats 22r36, 61%, rats ate )1 g and resultant small sample. It is not known why the uptake of the biscuit and cinnamon novel food by these rats was poor as the source and formulation of the food was the same as for oestradiol when a 94% uptake of)1 g was achieved.

No signs of malaise after intubation were observed in any rat and all investigated the SDS within 10 min of its introduction into the cage. Consumption of SDS resumed normal levels immediately after treatment.

3.3.2. Post-treatment tests

All rats investigated the novel food. In the first two trials, consumption varied

Ž .

significantly between groups one-way ANOVA: Ps0.001 , with T rats eating

negligi-Ž . Ž .

ble amounts Table 1 . However, in trial 3 3 weeks after treatment , all but two of the group T rats increased their consumption of novel food and the mean consumption was

Ž

not significantly different to that of the other groups one-way ANOVA: P)0.05, .

Table 1 . No further post-treatment tests were carried out with these rats.

3.4. Thiabendazole, 200 mgrkg

3.4.1. Treatment

After treatment, four of the T group rats appeared sleepy and withdrawn, and some showed pica. All rats approached the SDS food within 2 h and all but one ate overnight. Normal consumption of SDS returned to all but one T group rat within 2 days, and to all the groups within 4 days.

3.4.2. Post-treatment tests

In all five post-treatment tests, consumption differed significantly between groups Žone-way ANOVA: P-0.006, Table 1 , with T group rats eating less novel food than. the other groups. A degree of individual variation in response to thiabendazole at this

Ž .

dose was recorded; the three largest rats in the group 530–550 g males ate nothing in all post-treatment tests, while the majority of T group rats increased their consumption during post-treatment testing.

3.4.3. Comparison of CTA between compounds

In order to account for the difference in consumption between the two different

Ž .

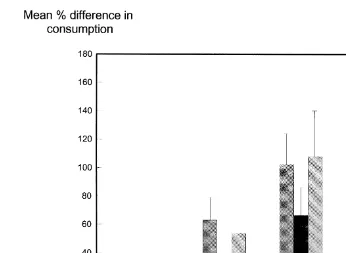

Fig. 1. Amount of novel food eaten during each post-treatment test, expressed as the mean percentage of the amount eaten on treatment day. Error bars are "1 S.E. Os17a ethinyl oestradiol, Cscinnamamide, T200sthiabendazole 200 mgrkg, T100sthiabendazole 100 mgrkg.

Ž

Significant differences existed for all post-treatment tests PF0.005 for all tests, Fig. .

1 , with oestradiol inducing the greatest reduction in consumption and cinnamamide and 100 mgrkg thiabendazole the least.

4. Discussion

All three compounds brought about a significant reduction in consumption of a novel food the next time the rats encountered it, and this effect persisted for a further two encounters for all compounds except thiabendazole at 100 mgrkg. This suggests that all three compounds are capable of inducing a CTA to a novel food. Data obtained from TC and C group rats show that neither intubation nor handling induced CTA. Oestradiol induced the strongest, most persistent CTA, with no sign of attenuation until after six post-treatment tests, with some individuals maintaining an aversion for )11

post-treat-Ž ment tests. This exceeds that reported for laboratory rats in previous studies e.g.,

.

Nicolaus et al., 1989a . Our data also suggest that it is possible to regenerate a robust

Ž .

( ) E.L. Gill et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 67 2000 229–240 238

the course of the experiment, although the reduction in consumption induced by thiabendazole at 200 mgrkg was still significant after five post-treatment tests.

The persistence of a CTA can be affected by the strength of and preference for the Ž

flavour of the referent food Green and Churchill, 1970; Etscorn, 1973; Garcia et al., .

1974; Nowlis, 1974 . In our experiments, minimisation of the number of rats necessi-tated the use of different novel referent foods. Although we did not specifically test for it, it is unlikely that there was any effect of these foods on CTAs. The stronger CTA induced by oestradiol relative to thiabendazole 100 mgrkg was due to the chemicals as

Ž .

these rats received the same food biscuit and cinnamon . The stronger CTA induced by oestradiol relative to cinnamamide might, however, suggest that sweet almond oats Žcinnamamide induced a weaker CTA, were it not for the fact that within thiabendazole,.

Ž .

sweet almond oats thiabendazole 200 mgrkg induced a stronger CTA than cinnamon Ž and biscuit, as would be expected with an increased dose of the chemical e.g.,

. oestradiol, Nicolaus et al., 1989a; lithium chloride, Burns, 1980 .

Some individual variation was noted in the rats’ CTA response to thiabendazole at 200 mgrkg, in which rats )530 g body weight showed a more persistent CTA than smaller individuals. It is assumed that a rat’s physiological response to the dose was proportional to its body weight, but this may not have been the case and these large rats may have received a physiologically larger dose.

With all compounds, the rats nearly always investigated the novel food after treatment, including making physical contact with it by picking it up or digging in the food bowl. The attenuation of the CTAs induced by cinnamamide and thiabendazole suggests that re-encountering the odour cues of the food did not induce a feeling of

Ž .

malaise, as reported in earlier studies Gustavson et al., 1974, 1976 , but this may have occurred for oestradiol.

The rats in our experiment had not eaten for at least 16 h and underwent no-choice tests from a static food bowl within a confined space. This was a hard test for the compounds and is unlikely to be representative of natural situations where alternative and, in some cases, mobile food sources may be available. Cinnamamide, for example,

Ž

appeared a much more effective CTA agent when tested in a two-choice test Watkins et .

al., 1998 . In most predator–prey situations, the predator need only hesitate before

Ž .

attacking for the prey to escape Gustavson et al., 1976 . No compound prevented the rats from handling the food; where the prey or target food is immobile, e.g., crops or eggs, CTA may still afford some protection because handling the food without eating is not an efficient foraging strategy and the consumer is likely to feed elsewhere in order to maximise energy intake.

Thiabendazole and cinnamamide are capable of inducing a short-term CTA and both are potentially safer to the target species and the environment than oestradiol. In our experiment, any malaise observed after intubation with these compounds was short-lived and no longer-term adverse effects were noted. The use of a second dose of

thiabenda-Ž .

zole to improve efficacy, as used by Gustavson et al. 1983 , warrants investigation; a second dose may also improve the efficacy of cinnamamide, but it may be safer to

Ž

deliver it at a lower dose rate. Both compounds are stable in the environment Gustavson .

et al., 1983; Polson, 1983; Zeigler et al., 1983; Gill et al., 1998 , and can be Ž

.

personal communication . Thiabendazole has the added advantage of being licensed for therapeutic use which would make approval for use as a CTA agent in the field less costly to obtain.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Land Use and Rural Economy Division of the UK Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. We thank Lowell Nicolaus for advice on the experimental protocol, Karen Ambrose for technical assistance and Joe Crocker and two anonymous referees for comments on the manuscript.

References

Ž .

Bernstein, I.L., Courtney, L., Braget, D.J., 1986. Estrogens and the Leydig LTW m tumour syndrome: anorexia and diet aversions attenuated by area postrema lesions. Physiol. Behav. 38, 159–163.

Borison, H.L., Wang, S.C., 1953. Physiology and pharmacology of vomiting. Pharmacol. Rev. 5, 193–230. Burns, R.J., 1980. Evaluation of conditioned predation aversion for controlling coyote predation. J. Wildl.

Manage. 44, 938–942.

Conover, M.R., 1989. Potential compounds for establishing conditioned food aversion in raccoons. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 17, 430–435.

Etscorn, F., 1973. Effects of a preferred vs. a nonpreferred CS in the establishment of a taste aversion. Physiol. Psychol. 1, 5–6.

Garcia, J., Hankins, W.G., Rusiniak, K.W., 1974. Behavioral regulation of the Milieu Interne in man and rat. Science 185, 824–831.

Gill, E.L., Feare, C.J., Cowan, D.P., Fox, S.M., Bishop, J.D., Langton, S.D., Watkins, R.W., Gurney, J.E., 1998. Cinnamamide modifies foraging behaviour of free-living birds. J. Wildl. Manage. 62, 872–884. Gill, E.L., Watkins, R.W., Gurney, J.E., Bishop, J.D., Feare, C.J., Scanlon, C.B., Cowan, D.P., 1997.

Ž .

Cinnamamide: a non-lethal chemical repellent for birds and mammals. In: Mason, J.R. Ed. , Repellents in Wildlife Management Symposium, Denver, CO, 1995. National Wildlife Research Center, Fort Collins, CO, pp. 43–52.

Green, K.G., Churchill, P.A., 1970. An effect of flavor on strength of conditioned aversions. Psychonom. Sci. 21, 19–20.

Gurney, J.E., Watkins, R.W., Gill, E.L., Cowan, D.P., 1996. Non-lethal mouse repellents: evaluation of cinnamamide as a repellent against commensal and field rodents. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 49, 353–363. Gustavson, C.R., 1977. Comparative and field aspects of learned food aversions. In: Barker, L.M., Best, M.R.,

Ž .

Domjan, M. Eds. , Learning Mechanisms in Food Selection. Baylor University Press, Waco, TX, p. 632. Gustavson, C.R., Garcia, J., Hankins, W.G., Rusiniak, K.W., 1974. Coyote predation control by aversive

conditioning. Science 184, 581–583.

Gustavson, C.R., Gustavson, J.C., Holzer, G.A., 1983. Thiabendazole-based taste aversion in dingoes and New Guinea wild dogs. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 10, 385–388.

Gustavson, C.R., Kelly, D.J., Sweeney, M., Garcia, J., 1976. Prey-lithium aversions: 1. Coyotes and wolves. Behav. Biol. 17, 61–72.

Jean, C., 1968. Nature et frequence des malformations mummeries du rat nouveau-ne en fonction de la dose d’oestradiol injectee a la mere gravide. C.R. Soc. Biol., 1144–1149.

Nadian, A.K., Lindblom, L.J., Cowan, D.P., 1993. Transit time of microcapsules through the gastrointestinal tract of the rat. In: Ninth International Symposium on Microencapsulation. p. 89.

( ) E.L. Gill et al.rApplied Animal BehaÕiour Science 67 2000 229–240 240

Nicolaus, L.K., Herrera, J., Nicolaus, J.C., Gustavson, C.R., 1989b. Ethinyl oestradiol and generalised aversions to eggs among free-ranging predators. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 24, 313–324.

Nicolaus, L.K., Nellis, D.W., 1987. The first evaluation of the use of conditioned taste aversion to control predation by mongooses upon eggs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 17, 329–346.

Nowlis, G.H., 1974. Conditioned stimulus intensity and acquired alimentary aversions in the rat. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 86, 1173–1184.

Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 1979. The Pharmaceutical Codex. 11th Edition The Pharmaceutical Press, London, UK.

Polson, J.E., 1983. Application of aversion techniques for the reduction of losses to beehives by black bears in N.E. Saskatchewan. Report to Dept. of Supply and Services, Ottawa, SRC Publication C-805-13-E-83. Revusky, S.H., Bedarf, E.W., 1967. Association of illness with prior ingestion of novel foods. Science 155,

219–220.

Semel, B., Nicolaus, L.K., 1992. Oestrogen-based aversion to eggs among free-ranging raccoons. Ecol. Appl. 2, 439–449.

Watkins, R.W., Gill, E.L., Bishop, J.D., 1995. Evaluation of cinnamamide as an avian repellent: determination of a dose response curve. Pestic. Sci. 44, 335–340.

Ž .

Watkins, R.W., Gurney, J.E., Cowan, D.P., 1998. Taste-aversion conditioning of house mice Mus musculus using the non-lethal repellent cinnamamide. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 57, 171–177.

Wittlin, W.A., Brookshire, K.H., 1968. Apomorphine-induced conditioned taste aversion to a novel food. Psychonom. Sci. 12, 217–218.

Yanagimachi, Y., Sato, A., 1968. Effects of a single oral administration of ethinyl estradiol on early pregnancy in the mouse. Fert. Steril. 19, 787–801.

Yasuda, Y., Kihara, T., Nishimura, H., 1981. Effect of ethinyl estradiol on development of mouse foetuses. Teratology 23, 233–239.