Comorbidity of PTSD and Depression: Linked or

Separate Incidence

In this issue of Biological Psychiatry, Breslau and col-leagues (2000) investigate the relationship between expo-sure to trauma, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and major depression disorder. The primary question focuses on whether exposure to trauma leads to major depression, independent of the development of PTSD.

The possibility that PTSD and depression are indepen-dent consequences of trauma exposure, with separate pathways leading to distinct psychiatric consequences, is highly intriguing from a clinical treatment perspective, since in treated samples of trauma victims the co-occur-rence of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and, often, substance-related symptoms is the rule rather than the exception. The complex clinical picture following trauma influences the nature of both psychoeducational and pharmacologic treat-ment strategies.

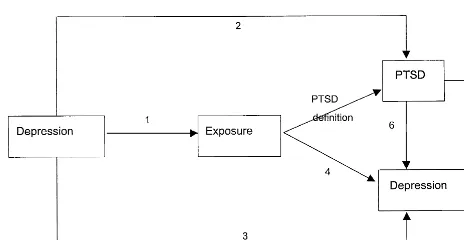

Since the appearance of PTSD in DSM-III in 1980, depression was found to be highly comorbid with this disorder. A large body of clinical and epidemiologic research has identified various links between extreme stress, depression, and PTSD symptomatology. Specifi-cally, as shown in Figure 1, pre-exposure depression has been found to be a risk factor for extreme stress (link 1; e.g., Breslau et al 1997; Bromet et al 1998), for PTSD (link 2; e.g., Breslau et al 1997; Bromet et al 1998), and for postexposure depression (link 3; e.g., Bromet et al 1982; Shalev et al 1998). In addition, depression was found to be a consequence of exposure (link 4; e.g., Bromet et al 1982; Brown and Harris 1978; Kendler et al 1999; Neria et al 2000). Finally, depression has also been associated with PTSD itself either concurrently (link 5; e.g., Shalev et al 1998) or following PTSD (link 6; Kessler et al 1995).

If there are different psychiatric outcomes emanating from trauma exposure, an important question is what predicts them. Clinical studies have found that PTSD is associated with changes in hypothalamic–pituitary–adre-nal (HPA) axis function (for a review, see Bremner et al 1999) and that patients with PTSD differ from those with depression with respect to cortisol response. It was also known that stress exposure may have long-term effects on the corticotropin-releasing factor/HPA axis (Bremner et al 1999). This is consistent with epidemiologic studies that show that PTSD and depression are often chronic and enduring conditions.

In addressing the relationship of PTSD and depression

using epidemiologic methods, Breslau and colleagues utilize a sophisticated statistical strategy, in analyzing responses from two community-based large samples: a young adult cohort drawn from a health maintenance organization in southeast Michigan (N 5 1007) inter-viewed prospectively at four points in time, and a nation-ally representative sample included in the cross-sectional National Comorbidity Survey (N5 5877).

The authors hypothesize that if trauma exposure in-creases the risk for major depression independently from PTSD, the results will show that persons exposed to trauma without developing PTSD will have a higher incidence of major depression than persons who were not exposed to trauma. In addition, if persons with PTSD have a higher risk of depression than exposed people without PTSD, the authors hypothesize that the relationship be-tween PTSD and major depression is either causal or due to a shared underlying vulnerability. Toward this end, the authors examine whether differences in types of trauma might account for differences in the risk for major depres-sion, since high-impact events, like rape and combat exposure, confer a higher likelihood of PTSD than less threatening events (e.g., Kessler et al 1995).

The findings suggest several important links between trauma exposure, PTSD, and depression. First, they con-firm that pre-existing major depression is a risk factor for both trauma exposure and PTSD. Second, the risk of (postexposure) major depression is higher in persons who develop PTSD than in people who do not. Third, the authors conclude that the differences in rates of major depression between exposed persons with and without PTSD could not be explained by the type of the exposure. The findings extend previous work by showing that the incidence of PTSD significantly increases the risk for first-onset major depression. Thus, they do not support the hypothesis that postexposure depression has a pathway separate from that of PTSD. Moreover, as noted by the authors, these findings suggest that the PTSD– depression co-occurrence in trauma victims might be due to common risk factors or vulnerabilities. This conclusion is consistent with previous reports that several risk factors for PTSD, such as female gender, family history of major depression, childhood trauma, and pre-existing anxiety and depres-sion, are also risk factors for major depression (Bremner et al 1993; Bromet et al 1998; Kessler et al 1995).

A central limitation in examining whether victims to

© 2000 Society of Biological Psychiatry 0006-3223/00/$20.00

trauma are at risk for psychiatric disorders other than PTSD is the current methodology applied in most of the investigations to date. Although the current DSM ac-knowledges that major depressive episodes can occur “in response to a psychosocial stress,” only PTSD and adjust-ment disorder require stress as a condition for receiving the diagnosis. Structured interview schedules, such as the Diagnostic Interview Schedule administered by Breslau et al (2000) and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview administered by Kessler et al (1995), were designed to follow DSM criteria and specifically inquire about PTSD symptoms in relation to traumatic exposures, but not about any other psychiatric symptoms. Thus, other disorders that are known to be outcomes of traumatic life events, such as major depression, are assessed separately, without being linked to an etiologic event as an essential part of the diagnostic procedure. This procedural differ-ence will inevitably reduce the strength of the relation-ships found between extreme stress and these psychiatric disorders relative to PTSD.

Moreover, in most studies only limited attention has been given to the contributions of predisposing factors or environmental consequences, such as postexposure stress-ful events and changes in social support. In contrast to the direct model of stress and its consequences found in much of the trauma literature, a number of comprehensive conceptual models of the stress-response process have been developed in parallel (e.g., Dohrenwend 1998; Kend-ler et al 1999). The findings from studies testing the adverse effects of stressful life events using these more inclusive models underscore the importance of personal predispositions, other concurrent situational factors and personal resources, social support, and coping abilities for understanding the impact of stressful experiences, includ-ing life threateninclud-ing events.

Methodologically, the most powerful design to test the hypothesis of separate occurrence of PTSD and other psychiatric disorders is a prospective cohort study that

carefully and reliably assesses the exposure, the onset, and offset of PTSD and other disorders (such as depression, anxiety, and substance abuse disorders), as well as longi-tudinal, including pre-exposure, measures of putative bi-ological markers. Thus, future studies should include large representative samples, independent ratings of exposure severity, ratings of mental health that are done indepen-dently of exposure, and reliable information on the timing of the onset and offset of disorders. Instruments having good congruence with clinical evaluation also need further development.

In conclusion, despite much progress, there still remains the need for a more comprehensive research agenda on the psychiatric outcomes of trauma and extreme stress. Ap-plying recent comprehensive conceptual models will pro-mote a better understanding of the nature of the stress-response process that occurs in the wake of traumatic events.

Yuval Neria Evelyn J. Bromet State University of New York—Stony Brook

Putnam Hall—South Campus Stony Brook NY 11794-8790

References

Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Charney DS (1999): The neurobi-ology of posttraumatic stress disorder: An integration of animal and human research. In: Saigh PA, Bremenr JD, editors. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Comprehensive Text.Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon, 103–143. Bremner JD, Southwick SM, Johnson DR, Yehuda R, Charney

DS (1993): Childhood physical abuse and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry150:235–239.

Breslau N, Davis CG, Peterson EL, Schultz LR (1997): Psychi-atric sequelae of posttraumatic stress disorder in women.Arch Gen Psychiatry54:81– 87.

Breslau N, Davis CG, Peterson EL, Schultz LR (2000): A second look at comorbidity in victims of trauma: The posttraumatic stress disorder-major depression connection.Biol Psychiatry

48:902–909.

Bromet EJ, Parkinson DK, Schulberg HC, Dunn LO, Gondek PC (1982): Mental health of residents near the Three Mile Island reactor: A comparative study of selected groups.J Preventive Psychiatry1:225–276.

Bromet E, Sonnega A, Kessler RC (1998): Risk factors for DSM-III-R posttraumatic stress disorder: Findings from the National Comorbidity Survey.Am J Epidemiol147:353–361. Brown GW, Harris T (1978):Social Origins of Depression.New

York: Free Press.

Dohrenwend BP, editor (1998): Adversity, Stress, and Psycho-pathology.New York: Oxford University Press.

Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA (1999): Casual

rela-Figure 1. Putative links between depression, trauma exposure, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Editorial BIOL PSYCHIATRY 879

tionship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression.Am J Psychiatry156:837– 841.

Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Nelson CB (1995): Posttrau-matic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey.

Arch Gen Psychiatry52:1048 –1060.

Neria Y, Solomon Z, Ginzburg K, Dekel R, Enoch D, Ohry A

(2000): Posttraumatic residues of captivity: A follow up of Israeli ex-prisoners of war.J Clin Psychiatry61:39 – 46. Shalev YA, Freedman S, Peri T, Brandes D, Sahar T, Orr SP,

Pitman RK (1998): Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma.Am J Psychiatry

155:630 – 637.

880 BIOL PSYCHIATRY Editorial