Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Futurism: Its Potential and Actual Role in Master of

Business Administration (MBA) Education

Robin T. Peterson

To cite this article: Robin T. Peterson (2006) Futurism: Its Potential and Actual Role in Master of Business Administration (MBA) Education, Journal of Education for Business, 81:6, 334-343, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.6.334-343

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.6.334-343

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 40

View related articles

ABSTRACT. In this article, the author

highlights the potential role of “futurism” in master of business administration (MBA) curricula and the conceivable offerings of futurism to business planners. This article serves as a corollary to educators in MBA business education and concerns to the nature of futurism, the benefits of futurism to managerial planning, the use of futurism in industry, and the various techniques for producing long-term scenarios. In addition, the author describes the results of an exploratory study on the extent of knowl-edge that MBA students possess on this subject. The results of this study suggest that MBA students are not well-informed about this approach.

Copyright © 2006 Heldref Publications

ome observers have concluded that business schools in general, and master of business administration (MBA) programs in particular, are suf-fering declines in relevance and influ-ence. According to one source,

When we examine the actual effects of business schools on the two outcomes of most relevance on importance, the careers of their graduates and the knowledge they produce, the picture is reasonably bleak. There is little evidence that mastery of the knowledge acquired in business schools enhances people’s careers, or that even attaining the MBA credential itself has much effect on graduates’ salaries or career attainment. (Pfeffer & Fong, 2002, p. 79)

However, the perspective of Pfeffer and Fong appears to depart from most conventional beliefs. More current research suggests that the rate of return for an MBA is high (although it has declined slightly in recent periods) and the demand for MBAs, on the part of recruiters, has increased and should continue to do so as the economy improves (Carmichael & Sutherland, 2005; Connolly, 2003; Van Auken & Chrysler, 2005).

What is apparent is that curriculum contents must be continually assessed to ensure that they are timely and germane to the needs of business (Barr & McNeilly, 2002; Dyrud & Worley, 2005; Mintzberg & Gosling, 2002). Studies are needed to determine what courses and course components are of

value to managers (Avison, 2003; Bai-ley & Ford, 1996; Pinard & Allio, 2005). Determining if, how, and when to keep up with the speed of business is becoming more important as business schools face increased competition and an ever-changing corporate climate (Barker & Stowers, 2005; Richards-Wilson, 2002). There are institutional and other obstacles to curricular assess-ment and change, but these must be overcome if genuine improvement is to be made (Hagen, Miller, & Johnson, 2003; Shelton, Yang, & Qian, 2005). In turn, various researchers in the field have directed their efforts to conducting studies that reveal directions that these academic programs can and should take (e.g., Boyatzis, Stubbs, & Taylor, 2002; Friis & Smit, 2004; Wanous, Reichers, & Austin, 2004).

Business graduate program profes-sors have made a number of innovations in an attempt to enhance the quality of their offerings. Some examples are (a) incorporating analysis of vintage (i.e., historical) cases (Peterson & Pratt, 2004), (b) adjusting the program to local culture (Rodrigues, 2005), (c) adding community service courses (Wittmer, 2004), (d) Using outdoor challenge training (Shivers-Blackwell, 2004), (e) Offering accelerated degree programs (Singh & Martin, 2004), (f) Using student-as-client models (Arm-strong, 2003), (g) Offering creativity

Futurism: Its Potential and Actual Role in

Master of Business Administration (MBA)

Education

ROBIN T. PETERSON

NEW MEXICO STATE UNIVERSITY LAS CRUCES, NEW MEXICO

S

instruction (McIntyre, Hite, & Rickard, 2003); and (h) including theory and analysis in the capstone strategy course (Greiner, Bhambri, & Cummings, 2003). In addition, there has been a very modest coverage of “futurism” in MBA education, but this effort does not appear to be extensive (Campbell & Helleloid, 2002).

The bulk of the research and practice in teaching futurism has arisen from psychology, rather than business admin-istration, but has the potential for appli-cation in MBA courses, where cross-fer-tilization from other academic fields is common (Tomkovick, 2004). I explored possible futurism applications in the MBA curriculum, which led to an exam-ination of what the term futurismmeans.

The Nature of Futurism

A comprehensive definition of

futures studiesis

a field of intellectual and political activity concerning all sectors of the psychologi-cal, social, economic, technologipsychologi-cal, political and cultural life, aiming at dis-covering and mastering the extensions of the complex chain of casualties, by means of conceptualizations, systematic reflec-tions, experimentareflec-tions, anticipareflec-tions, and creative thinking. [It is . . .] about goals, purposes, where we are going, how we get there and the problems and oppor-tunities we will encounter en route. (Sanal, 2003, p. 31)

The general orientation of futurists is to overcome the typical resistance to looking and thinking ahead (Bucen, 2004; Weiner & Brown, 2005). A relat-ed belief is that the future can be influ-enced (Nervy, 2004). In turn, there are certain characteristics of a futurist per-spective upon which most futurists agree and that distinguish studies in this area from those in many other disci-plines and fields of study. These charac-teristics include the following, as cited by Groff and Smoker (2004):

1. Seeing change as the norm and seeing change and as accelerating.

2. Seeing events as interrelated (with-in a whole systems context), not sepa-rate and unconnected;

3. Taking a holistic or whole systems perspective in looking at change;

4. Accepting as a premise that there are many alternative futures;

5. Distinguishing between possible, probable, and preferable futures;

6. Helping people realize that there are always consequences to what we do or do not do;

7. Understanding importance of ideas, values, and positive visions in creating a better future;

8. Empowering people to choose and act responsibly and consciously in the present; and

9. Accepting the importance of short-, medium-, and long-range planning.

Futurism is a field of inquiry and application that has suffered from a poor public image in the past (Hines, 2003; Masini, 1998). Criticism of futur-ists sometimes occurs, so when main-stream journalists deride futures research for being not relevant, they tend to dismiss the futures community as ill-informed (Mahaffie, 2003). How-ever, many widespread perceptions of futurism are not accurate. First in importance, it is not a “crystal ball” practice embracing appeals to the divine, illusions, and metaphysical sen-sation (Orndoff, 2004). Contrary to pop-ular opinion, futurists do not pretend that they can forecast future happen-ings. Rather, they recognize probable scenarios through the study of trends over time and current happenings. Once this has been accomplished, they rele-gate to others the task of capitalizing on the possible advantages that these changes offer and protecting themselves from the effect of adverse pressures (Shays, 2003). The field of futurism has developed to a stage that, at present, is deemed a science by some scholars (Hines, 2001).

Managers improve their ability to react to developments in the environ-ment when they generate multiple sce-narios and evaluate the chance that each one will happen and the impact that it will impose on the company (Barba-nente & Khakee, 2003). Often the sce-narios help identify products and ser-vices that are consonant with modifications in cultural norms, com-petition, customer demands, or technol-ogy. The scenarios may be based on consumer values (such as when con-sumers demand increasing convenience in paying bills), competitor actions

(such as when a competitor improves its customer service), economic condi-tions (such as when unemployment increases), technological advances, variations in the weather, new govern-mental regulations, and many other alterations (Aaker, 2005). Management can benefit through the generation of multiple scenarios because that permits them to make long-term plans with pro-visions for contingencies (Nervy, 2004). Bell (1997) has provided a suc-cinct case for the consideration of these potential future developments: “The future is not factual until it has become the past. Therefore futurists formulate their assertions in a range of alternative futures. Planners can then devise plans for each alternative and examine each of them, thereby stimulating creative ideas that people could have obtained in no other way” (p. 48). It is wellestab-lished that management should give more than lip service to long-run con-siderations (Brown, 2005; Foegen, 1993; Hines, 1999). Futurists tend to adopt a long-run outlook (one that is different from the majority of company planners, who largely address prevail-ing trends) and direct their attention to time spans, which may run 25 or more years into the hereafter (Coates, 2001; Delios, 2001; Groff & Smoker, 2004; Lach, 1999). Essentially, it is not func-tional to designate the future as taking place on such lengthy periods. There are a large number of variables that are operating and a large number of rela-tionships between the variables that inhibit designating a specific and par-ticular future set of conditions. Howev-er, it is feasible to recognize various possible futures, or an array of condi-tions into which the future may unfold that individually and collectively have meaning for those who are involved in long-run planning (Coates, 2003). The future cannot be seen as singular. On the contrary, many alternative futures that depend on present choices exist. In turn, these are better comprehended by understandings and interpretations of the past. The future is the sole field upon which humans can exert an impact because the past can only be construed, and the present is mainly determined by happenings and acts in the near or far-off past (Masini, 1998).

Planning Considerations

The research and professional litera-ture cites many instances where faulty planning is responsible for business fail-ure (Knotts, Jones, & Udell, 2003). In turn, plans can be inadequate when they neglect flexibility in the unstable envi-ronment that envelops numerous firms, and even when the environment is stud-ied, alterations may be misdiagnosed or their underlying patterns not correctly detected (Duchon & Ashmos, 1999).

When managers do plan effectively, they focus their attention on the major goals of the company and the objectives of the central stakeholders. Following this, they generate and assess programs that can allow the company to achieve the more important goals. Next, they evaluate, the premises that support the programs. These are theories on points such as customer desires, competition, the company, its personnel, and its financial condition. Futurism is of value in this process because it assists man-agers in evaluating the premises and judging the degree to which they are consonant with the scenarios that appear to have a strong probability of materializing (Shays, 2003). Observant study may suggest that superior premis-es should be used or existing premispremis-es altered if the company’s planning efforts are to be well conceived.

There are occasions when plans do not produce sought after effects because managers have not taken the long-range future into account (Foegen, 1993; Isser-man, 1985). Of course, the result may be that the firm pursues strategies with undesired ramifications. Experience sug-gests that planning is one of the major avenues for using future studies as a means of overcoming obstacles con-fronting the company. Those managers who focus their attention on the future often find that this significantly enhances their planning endeavors. To accomplish this, they devote adequate consideration to the future outcomes of planned strate-gies and programs. In this regard, man-agers are well advised to identify the desired future state and determine how it can be realized in light of the most likely scenarios for the future. This activity may necessitate departing from conven-tional methods of operation and placing

the future in the forefront of decision making (Cole, 2001).

The Use of Futurism in Industry

One can make a strong case for the proposition that when independent managers are involved in planning they should evaluate the status of the future environment if their endeavors are to be successful. Cultural values, method of operation, employee orientations and skills, financial procedures, and other influential variables are undergoing continual evolution (Orndoff, 2004; Sanal, 2003). Managers are confronted with the necessity of developing means for using information to produce strate-gies that are appropriate for the compa-ny (Slaughter, 2002).

It is apparent that social goals and standards in the United States and most other nations are successively taking on innovative forms (Mathews, 2001). In the opinion of some futurists, the upcoming 25 years will involve more changes than those that occurred over the past 100 years, and, if this tran-spires, planning innovations that are at least four times as rapid and effective as they had been in the past are needed (Kipp, 2001). An accomplishment of this magnitude will require recognizing complacency as the major obstacle to innovation and improved management.

There are numerous potential applica-tions of futurism to business planning. In fact, envisioning the future is a process that can benefit plans in such fields as operations, marketing, finance, human resources, logistics, and communications.

Environmental scanning is a process that can be improved through exten-sions to future time periods. It is of vital importance that, in today’s world of uncertainty, organizations stay abreast of environmental changes that can affect the future, and special expertise is required to realize how an event or trend might affect an institution in the future (Pashiardis, 1996). Organizations must tailor specific sources of external infor-mation, devise a method to collect the information, and use the information effectively in the planning process and in building the future. An advantage of this kind of screening is that it provides all individuals with the opportunity to

contribute to the strategic planning process (Pashiardis).

Futurism also has a role to play in product innovation activities. This tool can assist in guiding management in efforts at developing offerings that are valued by a significant set of customers and that reflect the abilities of the organi-zation. Each of these two essential com-ponents should be pulled apart and looked at separately, in terms of their present and expected future status (Miller, 2001). The focus should be on customers and away from internal issues, and separate treatment of these two fac-tors the odds of accomplishing this.

An application of futurism to product innovation can be found in the area of home construction. Hiat (1988) com-bined research on aging and environ-mental design with futurism and brain-storming to suggest possibilities for smart housing for the aging. Smart housing is defined as homes in which systems and appliances can command each other through advances in wiring therefore, that require less management and offer security, thereby making older adults’ lives easier. The Dail Mil Ideal Home Show, held annually in London, provides examples of homemaking futurism and provides companies that have developed concepts of homes for the future the opportunity to sell their offerings to consumers. Many of these homes feature extensive Internet tech-nology (Wishart, 2000).

Futurism has a potential impact on human resource and personnel manage-ment as well. In this regard, researchers have provided a number of scenarios that appear to have a high probability of occurrence in the future, including the professionalization of the personnel field, issues of comparable worth, and the assessment and psychological testing of employees, particularly older and handi-capped (Hunt, 1984). Another applica-tion in the human resource field is in careers and employment opportunities. Here, changes in the world of work (e.g., the decline of heavy industry and the rise of careers in the electronic cottage) have important implications for future job seekers and placement personnel alike (Navin & Burdin, 1986). Yet another application is futurism consultancy that specializes in workplace trends, such as

midcareer retirement. Scholars in this field study what individuals do away from work, how midcareer retirements fit in with family obligations, and what the trend toward midcareer retirement means for managers (Wellner, 2001).

Given that there are business func-tions that can link with futurism, how can managers make operational use of this technique? The following section focuses on how the method can be implemented.

Applying Futurists’ Methods

Managerial planning may benefit through correct interpretation and appli-cation of futurist techniques, but these tools are not the only ones that are valu-able. Other potentially useful inputs are sales forecasting, portfolio analysis, marketing research, creative thinking stimulators, evaluation of rival services, environmental scanning programs, reengineering, and SWOT (Strengths Weaknesses Opportunities Threats) analysis. Each of these methods can assume a significant role in well-con-ceived planning. Conversely, the futurist pattern provides specific advantages that may not be equaled by the others. For example, marketing research frequently centers on future developments and states, but even when this is the case, the research future time span is only moder-ate (Comoder-ates, 2003). This does not suggest that such research lacks value. However, it can operate in conjunction with futur-ism, which typically serves as a comple-ment to, not a substitute for, this and other approaches to improve planning.

Two avenues are open for using futur-ism as a tool for those managers who are involved in planning. The first involves making use of work already compiled by others and published in print or electron-ic formats. This is called using secondary derivation. The second approach is one in which managers undertake their own futurist studies and perspectives of the future (i.e.,primary derivation).

Secondary Derivation

A large number of seasoned profes-sionals have produced and made avail-able various insights regarding future approaches, methods, happenings, and trends and many can readily be acquired

by managers who seek specialized guid-ance. A major advantage of secondary derivation sources is that many of them contain work prepared by experts with the education and experience that is sought by industries. In addition, consid-erable information is free of charge or costs a moderate price. Further, most of the insights are available in a reasonable time period. However, there are draw-backs associated with secondary deriva-tion sources. One is that their output may not be precisely what is desired by the manager in question because they are ori-ented toward an audience rather than an individual. Further, many of the outputs are accessible by others, including rivals. What follows is an overview of some of the secondary derivation sources that have considerable potential and should continue in this role. My focus is not to describe the total set or even a large pro-portion of the sources in existence, but to address a small number with a track record of accuracy and reliability.

Future Survey

The Future Survey is a monthly abstract of books, articles, and reports concerning forecasts, trends, and ideas about the future. Access is limited to subscribers ($98 per year) and institu-tional members ($145 per year) and is found at http://www.wfs.org/fsurv.htm. It contains concise and nontechnical abstracts of recently published literature. Selections are made from more than a hundred book publishers, a score of research institutes, leading newspapers, and dozens of key magazines and schol-arly journals. Noteworthy individual items in each 20-page monthly issue are selected as “Highlights,” and clusters of significant ideas are identified and sum-marized in “Connections.” The editor adds brief critical comments to items (many readers consider this as the best article in Future Survey). The editor, Dr. Michael Marien, has more than 20 years of experience in identifying and inter-preting the futures-relevant literature.

Introduction to Future Studies Home Page

The introduction to the Future Stud-ies home page (http://www.csudh.edu/ globaloptions/IntroFS.HTML) provides

a wide selection of futures-oriented materials at no cost. It includes a brief history of the future studies field, a range of futurist views and perspectives, characteristics of a futurist perspective, key subject studies by futurists, method-ologies for studying change and the future, key organizations involved in the study of the future and change, future studies conferences, and future studies universities and programs. Relevant writings (i.e., abstracts, outlines, papers, and articles) are also provided.

Foresight

Foresight(http://pippo.emeraldinsight. com) is a vehicle for the publication of research, business analysis, and policy thinking. The journal provides a forum for debate on the important social, eco-nomic, political, and technological issues that are shaping the future. It is a source of information about futures activity from around the world. Generally, it is intended as a resource for those in busi-ness and nonprofit organizations, provid-ing a long-term perspective to inform managers about possible decisions and actions.

Futures: The Journal of Policy, Planning, and Futures Studies

Futures: The Journal of Policy, Plan-ning, and Futures Studies (http://www. elsevier.com/locate/futures) is a multi-disciplinary, refereed journal concerned with medium- and long-term futures of cultures and societies, science and tech-nology, economics and politics, organi-zations and corporations, environments, and individuals and humanity. It covers methods and practices of futures studies and seeks to examine possible and alter-native futures of all human endeavors. It strives to promote divergent and plural-istic visions, ideas, and opinions about the future.

Futures Research Quarterly

The Futures Research Quarterlyis a studious journal whose editors endeavor to stimulate and generate communica-tions between researchers and managers in a diversity of disciplines and various social, political, economic, and geo-graphic areas. The articles are scholarly,

but written in a manner that is meaning-ful to practicing managers rather than in academic jargon. This journal spans a wide coverage of topics. It attempts to provide informed knowledge and schol-arship in the methods and implementa-tion of futures studies and their role in managerial planning and policy forma-tion and the applicaforma-tion of plans in the business sector.

The Futurist

The Futuristvolume takes the format of a bimonthly magazine. This work has been in existence since 1967 when it was first introduced by the World Future Society, a nonprofit organiza-tion. The Futurist’s editors do not strive to promulgate notions on what the future will be like or what it would include in a hypothetical supreme con-dition. Instead, they attempt to take on the role of an impartial concept sound-ing board with their journal. The vari-ous issues provide feature articles pro-duced by experienced specialists in an extended range of disciplines.

The Millennium Project

Another source,The Millennium Pro-ject, is produced by the American Coun-cil for the United Nations University. This volume presents yearly communi-cations on anticipated future occur-rences. Theodore Gordon, frequently mentioned as one of the leading modern futurists, developed the project. Gordon is one of the inventors of the Delphi process, a technique that is extensively used in futures and other studies. In addi-tion, this individual was an innovator in the use of computers to enlarge the capa-bilities of future exploration practition-ers. The project’s yearly report sets forth combined estimates of various experts, bearing on the subject areas under con-sideration. A recent report,2003 State of the Future(2005); is accompanied by a 2,500 page compact disk (for more detail, consult http://www.stateofthe future.org).

GW Forecast

Another potentially valuable contribu-tor of intelligence is George Washington University’s GW Forecast (www.GW

Forecasts.gwu.edu). It presents material-izing futurist methods and policies that are developed by a World Wide Web of well-versed experts. This itemized group-ing of futures intelligence has been shaped over the past decade and is pri-marily dedicated to technological devel-opments. In the same fashion as The Mil-lennium Project, it is based on a Delphi process arising from the intellectual con-tributions of learned futurists who spe-cialize in both theory and applications.

World Future Society

The World Future Society (http:// www.wfs.org) is an organization that generates a large number of Web forums. Prominent samples of these include (a) the Cyber Society Forum, which endeavors to predict how future life may take place, (b) the Opportunity Forum, which sets forth various thoughts regarding opportunities to improve professional and personal life, (c) the Utopias Forum, which contains a variety of essays on preferred future states, and the Methodologies Forum, which furnishes suggestions and poten-tially useful methods for futuring efforts and insights on the objectives for study-ing the future.

In addition to the secondary derivation contacts reported above, many futurists furnish useful offerings through newslet-ters, Web pages, books, monographs, reports articles, and other conduits. Among the more widelycited, respected, endorsed, and read of these are those written by Joe Coates, Elenora Masini, William Strauss, James Morrison, Ryan Mathews, Rosita Delios, Marita Wesely-Clough, Harold Linstone, Anita Rubin, Neil Howe, William Renfro, Peter Schwartz, and Murray Turoff.

Primary Derivation

Some managers may prefer to con-duct their own futurist studies rather than relying upon the work of others. What one learns from these primary derivation efforts is normally confiden-tial (not made available to others, includ-ing rivals) and could focus on issues of particular concern to one’s own compa-ny. Numerous recommendations and suggestions, which can be of value to managers in virtually any industry are

available. Several that are of particular importance are discussed in this section. To study the future, it is necessary to take a long-term trend focus, and not be deterred by fads and short-term changes. This is a very important per-spective that should be adopted as a pri-mary principle of pripri-mary derivation. “The fundamental features of cultures and societies change very slowly and cannot be identified except in the long term. And yet this is generally the pace at which the most profound changes take place, which explains why special instruments and methods are necessary to measure them” (Delios, 2001, p. 3).

In this section I list a number of pri-mary derivation methods that can be used by managers without specialized training and experience. I have included various, more complex, techniques that do require considerable expertise at the end of the section.

Groff and Smoker (2004) proposed a generally accepted, overall practical, and uncomplicated approach for con-ducting future studies. The steps in this approach are as follows: (a) specify the values sought by the organization (such as increases in return on invested capital or customer satisfaction), (b) analyze the present and forecast future develop-ments, (c) formulate designs of alterna-tive futures (predict what various possi-ble futures might be like), (d) evaluate the designs of alternative futures (judge the desirability of the various possible futures), (e) draft transition strategies of how one gets from one’s starting pace to where one wants to end up. (f) imple-ment policies, (g) receive feedback on whether or not these policies are having the planned effects, and (h) adjust strategies and policies on the basis of feedback.

Diamond (1997) also proposed a series of very practical suggestions on the topic of “How to be your own futur-ist.” Diamond’s suggestions are:

1. In the course of each week, choose and read a trade magazine originating in a different industry. This can be insightful because it furnishes new information and additional perspectives and positions.

2. Engage in an ongoing process of reading classical works. Following the thinking of writers such as Homer,

fucius, and David Ricardo can produce suggested scenarios that may recur at a future time.

3. Upgrade your listening capability and engage in more listening effort. Ability in this area is an important pre-requisite for learning. It is well estab-lished that practice can improve listen-ing skills.

4. Volunteer in nonprofit institutions. Everyone who is involved in a service organization has an equitable proportion of influence. In this circumstance, one does not have authority over others or expect obedience to others who have greater degrees of power, so new ideas and suggestions often can be acquired without difficulty.

5. Permit your own or other children to enlighten you in a subject area where they are more knowledgeable than you are. This activity can build modesty and humbleness and can lead to innovative and newly recognized scenarios of the future.

Cole (2001), a highly regarded futur-ist, also suggests a structured program for engaging in futures studies:

1. Realize that many alternative futures may come into existence.

2. Make an effort to differentiate between potential, likely, and desired futures.

3. Try to forecast anything (favorable or unfavorable, likely or unlikely) that could come into being for every poten-tial future scenario.

4. Concentrate on the more likely future scenarios. What is most probable to come into existence in upcoming time periods?

5. Expand upon and amplify desired futures. What are the most preferred future scenarios?

Scenarios have a prominent place in the futurist activities of many business firms. These are possible sequences of events that could happen in the future, based on certain initial conditions or assumptions and what could follow from that (Groff & Smoker, 2004). Futurists often construct at least two or three dif-ferent scenarios about the future in some area, believing that different alternative futures are possible. Examples include best case, worst case, most probable

case, and other type scenarios. The aim is not to predict the future but to be able to use exploratory or anticipatory sce-narios to infer what paths should be fol-lowed and what directions are preferred (UNESCO, 1995).

A scenario begins when we ask, “What would happen if this occurred?” Once the question is posed, one can begin to imagine the consequences of the event. This makes managers aware of potential problems that might occur if certain actions were taken. Plans should be made as to the preparations that would be necessary for the event to occur. Management can then make deci-sions, such as abandoning proposed actions or preparing to take precautions that would minimize the problems that would result.

Van der Werff developed a series of scenario planning steps that can be use-ful in guiding managers (van der Werff, 2000). The steps are (a) specify the major issue or decision you are facing; (b) isolate the key drivers (i.e., external forces) affecting your company; (c) select three drivers that are both impor-tant and the most uncertain; (d) write three scenarios (short stories) of the future, each highlighting a different key driver; (e) give each scenario a pithy, memorable name; (f) determine the implications of each scenario for the issue being considered; (g) consider possible strategies to respond to each implication; (h) select indicators that suggest that a particular scenario is unfolding; and (i) act in a timely and appropriate manner as a particular future unfolds.

A possible course of action is to use normative forecasting. This involves describing all the possible future scenar-ios by using all available methods, deciding which scenario would be good for the firm, then finding a way to attain that scenario. What needs to be done is often relatively clear. How to get it done relies on how much those involved want it, what they are willing to tolerate, and how much they are prepared to pay to make it happen (Pohl, 1996).

A method that has considerable merit is to seek out unfulfilled or unknown consumer needs and wants that are not being met by companies and other par-ties (Abraham, 2003). Some examples

are reducing obesity, reducing water pollution, preserving the stock of non-renewable resources, providing job opportunities, discovering economical alternative sources of energy, and deal-ing with the population explosion. The incidence of these and other significant needs can direct business, government, nonprofit, and other organizations into programs specifically designed to satis-fy them. Focusing on studies of needs and attempts to satisfy them can pro-duce concepts of the future that have a high likelihood of happening.

A somewhat similar technique is to use personal travel as an avenue for insights (see Paul, 2003). Taking advan-tage of trips to both domestic and for-eign locations can reveal both long- and short-term patterns and unfamiliar developments. Conducting dialogues with others who reside in these locales, inspecting their products and service offerings, studying their promotion materials, perusing what they read, and surveying their television and radio transmissions may reveal novel trends and happenings. On the domestic front, novel products and services, social norms, techniques, approaches, and fashions are often initiated in the distant eastern and western states and later move inward to interior states. Particu-lar foreign localities, including Japan and Brazil, are often the point of origin for forthcoming trends in other coun-tries. Furthermore, trips to exotic cities, such as Marakesh, can bring forth fresh perceptions.

The analysis of demographic data is a method that can generate novel under-standings. Changes in variables, such as marital status, birth rates, mortality, employment, expenditures, gender, eth-nicity, and wealth, can reveal later alter-ations in other variables, such as pur-chasing behavior and methods of motivating employees. Data sources indicate, for example, that the propor-tion of extended families, in both devel-oped and developing nations, is declin-ing, relative to the proportion of two-cohort units. The outcomes could include increased demand for homes for elderly persons, changes in the trans-portation needs of the population, and fewer cottage industries. Long-term pat-terns in demographics such as these are

continually occurring and often portend important developments to come.

Observation is an obvious but fre-quently overlooked avenue for produc-ing informed visions of future develop-ments. Shopping in retail outlets, strolling through railroad and bus termi-nals, eavesdropping on dialogues in restaurants and bars, surveying employ-ees on the job, noticing traffic patterns, and other means of observing domestic and foreign culture can lead to useful impressions. “When a new word enters the lexicon, a color becomes fashion-able, a design influence hits the main-stream or a lifestyle change becomes socially acceptable, changes may be on the way” (Paul, 2003, p. 42). Observa-tion appears to have a solid role in stud-ies of the future.

New visions can result from conver-sations with others and associated dis-closures of their ideas about the future. New vistas may arise from dialogues with those who differ from us in such characteristics as source of income, gender, age, self-image, location, reli-gious preferences, and other attributes (Abraham, 2003). Interpersonal com-munication of this kind is undertaken through various means, such as person-to-person or over the Internet through channels like communication boards and chat rooms (Halal, 2004).

Ostensibly an unlikely, quixotic, and inordinately unrealistic method, survey-ing science fiction publications has been found to be enlightening to some extent. Some futurists browse through science fiction manuscripts and undertake a pro-gram of construing and then developing unconventional and even extreme sce-narios (Jennings, 2004). Shostak (2000) has observed that childrens’ electronic games, fiction books, and cartoons can all be employed for this purpose.

There are a number of futurist meth-ods beyond those covered in this article. Many of these are very complex and require specialized knowledge to use, including those listed below. A descrip-tion of each and further references for pursuing the methods are available in Delios (2001), Groff and Smoker (2004), Joels (2004), and Sanal (2003).

1. Trend extrapolation: Project past trends into the future.

2. Analogies: Use historical and nat-ural precedents to form the basis of meaningful forecasts. For example, comparing the rise and fall of Ming dynasty naval exploration with contem-porary space exploration.

3. Dynamic systems analysis and computer modeling: Show how vari-ables interact with each other within a whole systems context over time.

4. Simulations and games: Take vari-ables from reality and create a comput-er model or simulation showing how these variables might interact over time. 5. Cross impact analysis: Show how choices concerning one variable interact with choices on another variable, pro-viding a table of all possible combina-tions of choices for each variable and showing which combinations are viable and which are not.

6. Technological impact assessment: Look at how new developments will impact the environment. This is related to social impact assessment, or looking at how new developments will impact society or one community.

7. Futures wheels: Conduct group brainstorming to quickly predict what some of the first, second, and third order consequences might be if an event were to occur or if some change were to take place in the future. Everything that fol-lows from this event is placed in the center of the futures wheel.

8. Intuition and intuitive forecasting: Use a right brain experience in which you suddenly “know” something to be true or you suddenly see patterns and relationships you did not see before.

9. Experiments in alternative lifestyles: Try out alternative values in practice. New fads or alternative lifestyles that respond to social needs often become mainstream in time.

10. Social action to change the future: Joining together with others to educate people on an issue and work for mean-ingful change often reveals that the efforts can affect and help to alter the future.

11. Relevance trees: Map out the sequence of events and arrange them in the order that is required to get from where you are now to where you want to be as your end goal by some future date. 12. Agent modeling: Construct com-puter models in which “agents”

popu-late the screen and are given certain, usually simple, rules of behavior.

13. Complexity modeling: Use con-cepts of nonlinear dynamics in the mod-eling of complex systems.

Individual managers may find that one method or some combination of methods is instrumental in drafting sce-narios that are pertinent for their firms in future times. It is generally conceded that this activity is probably somewhat more an art than it is a science and that it requires some degree of trial and error for full results. Generally, probing the future necessitates training and rehearsal, and the more managers prac-tice it and hold dialogues with others, the more proficient they can become in this endeavor (Coates, 2003).

METHOD

Are futurism philosophies and meth-ods covered in MBA curricula in the United States? I undertook an exploratory study to gain knowledge about the degree to which students are informed about the potential role of futurism in managerial planning. This study is entirely exploratory; the field has not been subjected to thorough analysis. I developed a questionnaire using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = dis-agree very strongly to 5 = agree very strongly), pretested it with a sample of 15 MBA students in a southwestern university, and subsequently revised it in light of pretest feedback. The Appendix outlines the questionnaire’s contents. I mailed a cover letter, accompanyied by 15 questionnaires to the marketing department chair of 40 randomly selected universities in 40 states, explaining the goals of the study, and requesting the chair to pass on the cover letter and questionnaires to a professor who taught the MBA marketing management or strategy course. The professors collected the completed questionnaires and mailed them to me. I mailed follow-up letters to nonresponding universities. The sampling frame was the American Marketing Association 2004 member-ship directory. The study resulted in 217 questionnaires that were correctly completed (a response rate of 36.2%).

RESULTS

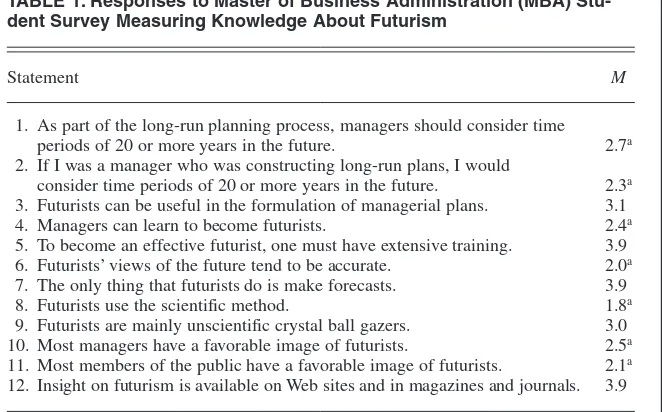

Table 1 shows the mean response val-ues for each of the 12 statements on the questionnaire. I used ttests to assess the significance of each difference between the mean scale value and the midpoint of the listed scale values (3.5) for each statement. As Table 1 shows, the mean values for 7 of the 12 statements (State-ments 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 11; see Appendix) were significantly different from the midpoint at the .05 level.

DISCUSSION

My goals in this article were to furnish an evaluation of the potential of futurism techniques in contributing to managerial planning, to outline procedures that can be used in this area, and to assess MBA student insights on this technique. I con-sidered the essence of futurism, how the future can affect planning in industry, and applications to managerial practice. It is evident, on the basis of the extant lit-erature, that substantial consideration of the future is required for well-conceived managerial planning. Furthermore, there is evidence that futurism may contribute to the planning function and a number of sources of information and futurist tech-niques are available for use. In addition, I designed this exploratory study to mea-sure the degree to which MBA students are informed on this subject.

The inquiry indicated that the MBA students did not show an inclination to focus on future periods of 20 years or more (Statements 1 and 2). They were noncommittal on the value of futurism in planning and did not show strong support for the idea that managers could become futurists and that extensive training was needed to master this disci-pline (Statements 3–5). They felt that futurists’ scenarios of the future were not especially accurate (Statement 6). They saw futurists as concentrating on forecasting and not practicing the scien-tific method (Statements 7–9). The image of futurists was somewhat unfa-vorable, as they saw it (Statements 10 and 11). Finally, they were not aware of the degree to which futurism intelli-gence is available in print and online formats (Statement 12).

The academic and popular literature conveys the impression that planning efforts can be upgraded and strength-ened should the futurist orientation be applied. In fact, specialization in this and related areas is required by many MBA recruiting firms (Schelthaudt & Crittenden, 2005). There is no obvious reason why this would not hold for the majority of industries and economic sectors. I have set forth the output of an exploratory inquiry that suggests that many MBA students have not gained a working knowledge of the promise and practice of this technique. More

inten-sive focus on the long-term future may provide planning progress that exceeds the resources committed to this process. This is a perspective that those who teach planning-oriented MBA courses may want to consider.

The composition of many MBA cur-ricula is constrained by the limited num-ber of courses that can be offered or required of students (Haskins, 2005). It may be difficult to justify the existence of a course that is devoted solely to futurism. However, the major philoso-phies and perspectives and many of the methods of futurism can be integrated into existing courses in management and marketing, particularly those that deal with strategy. Future managers can ben-efit considerably from this arrangement.

Finally, the study set forth in this arti-cle was very limited in scope; There-fore, more comprehensive investiga-tions into the area should be undertaken.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Robin T. Peterson, Department of Marketing, Box 5280, College of Business Administration and Economics, New Mexico State University, Las Cruces, NM 88003.

E-mail: Ropeters@nmsu.edu

REFERENCES

Aaker, D. A. (2005). Strategic marketing manage-ment. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Abraham, S. (2003). Experiencing strategic con-versions about the central forces of our time.

Strategy and Leadership, 31, 61–64.

Armstrong, M. J. (2003). Students as clients: A professional services model for business. Acad-emy of Management Learning & Education, 2, 371–375.

Avison, D. (2003). Information systems in the MBA curriculum: An international perspective.

Communications of AIS 2003, 11, 117–128. Bailey, J., & Ford, C. (1996). Management as a

science versus management in practice in post-graduate business education. Business Strategy Review, 7, 7–12.

Barbanente, A., & Khakee, A. (2003). Influencing ideas and aspirations: Scenarios as an instru-ment in evaluation. Foresight: The Journal of Future Studies, Strategic Thinking, and Policy, 5, 3–15.

Barker, R. T., & Stowers, R. H. (2005). Learning from our students: Teaching strategies for MBA professors. Business Communication Quarter-ly, 68, 481–487.

Barr, T. F., & McNeilly, K. M. (2002). The value of students’ classroom experiences from the eyes of the recruiter: Information, implications, and recommendations for marketing educators.

Journal of Marketing Education, 24, 168–174. Bell, W. (1997). Foundations of futures studies:

Human science for a new era. New York: Trans-action.

Boyatzis, R. E., Stubbs, E. C., & Taylor, S. N.

TABLE 1. Responses to Master of Business Administration (MBA) Stu-dent Survey Measuring Knowledge About Futurism

Statement M

1. As part of the long-run planning process, managers should consider time

periods of 20 or more years in the future. 2.7a

2. If I was a manager who was constructing long-run plans, I would

consider time periods of 20 or more years in the future. 2.3a

3. Futurists can be useful in the formulation of managerial plans. 3.1 4. Managers can learn to become futurists. 2.4a

5. To become an effective futurist, one must have extensive training. 3.9 6. Futurists’ views of the future tend to be accurate. 2.0a

7. The only thing that futurists do is make forecasts. 3.9 8. Futurists use the scientific method. 1.8a

9. Futurists are mainly unscientific crystal ball gazers. 3.0 10. Most managers have a favorable image of futurists. 2.5a

11. Most members of the public have a favorable image of futurists. 2.1a

12. Insight on futurism is available on Web sites and in magazines and journals. 3.9

aSignifies a mean scale value that is significantly different from the midpoint on the scales (3.5),

according to a ttest at the .05 alpha level.

(2002). Learning cognitive and emotional intel-ligence competencies through graduate man-agement education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 1, 150–162.

Brown, S. (2005). Science, serendipity, and the contemporary marketing condition. European Journal of Marketing, 39, 1229–1234. Bucen, I. H. (2004). Futures thinking and the

steep learning curves of the twenty-first centu-ry. Foresight: The Journal of Future Studies, Strategic Thinking, and Policy, 6, 121–127. Campbell, K., & Helleloid, D. (2002).

Perspec-tive: An exercise to explore the future impact of new technologies. Journal of Product Innova-tion Management, 19, 69–81.

Carmichael, T., & Sutherland, M. (2005). A holis-tic framework for the perceived return on investment in an MBA. South African Journal of Business Management, 36, 57–70. Coates, J. F. (2001). Futures and technology

assessment research for business clients. Leon Kozminski Academy of Entrepreneurship and Management (pp. 10–11). Warsaw, Poland: L.K. Academy.

Coates, J. F. (2003). Why study the future?

Research Technology Management, 46, 5–8. Cole, S. (2001). Dare to dream: Bringing futures

into planning. Journal of the American Plan-ning Association, 67, 372–384.

Connolly, M. (2003). The end of the MBA as we know it? Academy of Management Learning and Education, 2, 365–371.

Delios, R. (2001). Trends for the international future: Studying the future: Who, how, & why. Retrieved July 31, 2005, from http://www.inter-national-relations.com/pp/ProspectsI-htm Diamond, D. (1997). How to be your own futurist.

Fast Company, 6, 78.

Duchon, D., & Ashmos, D. P. (1999). The central role of sensemaking for managing small busi-ness as a complex adaptive system. Journal of Business & Entrepreneurship, 11, 61–65. Dyrud, M. A., & Worley, R. B. (2005). Teaching

MBAs, part 1. Business Communication Quar-terly, 68, 479–480.

Foegen, J. H. (1993). Filling the gaps: Challenges for today and tomorrow. Business Horizons,36, 77–80.

Friis, L. B., & Smit, E. (2004). Are some fund managers better than others? Managerial char-acteristics and fund performance. South African Journal of Business Management, 35, 31–41. Greiner, L. E., Bhambri, A., & Cummings, T. G.

(2003). Searching for a strategy to teach strate-gy. Academy of Management Learning & Edu-cation, 2, 402–421.

Groff, L., & Smoker, P. (2004). Introduction to future studies. Retrieved March 2, 2005, from http://www.csudh.edu/global_options/IntroFS. HTML

Hagen, R., Miller, S., & Johnson, M. (2003). The disruptive consequences of introducing a criti-cal management perspective into an MBA pro-gram. Management Learning, 34, 241–258. Halal, W. E. (2004). The intelligent Internet: The

promise of smart computers and e-commerce.

The Futurist, 38, 27–33.

Haskins, M. E. (2005). A planning framework for crafting the required curriculum phase of an MBA program. Journal of Management Educa-tion, 29, 82–110.

Hiat, L. G. (1988). Smart houses for older people: General considerations. International Journal of Technology & Aging, 1, 11–30.

Hines, A. (1999). The foresight amphibian in the corporate world. Foresight: The Journal of Future Studies, Strategic Thinking, and Policy, 1, 382–384.

Hines, A. (2001). Foresight and the cult of per-sonality. Foresight: The Journal of Future Stud-ies, Strategic Thinking, and Policy, 3, 83–84. Hines, A. (2003). The futures of futures: A

sce-nario salon. Foresight: The Journal of Future Studies, Strategic Thinking, and Policy, 5, 28–35.

Hunt, T. (1984). Futurism and futurists in person-nel. Public Personnel Management, 13, 511–520.

Isserman, A. (1985). Dare to plan: An essay on the role of the future in planning practice and edu-cation. Town Planning Review, 56, 483–491. Jennings, L. (2004). Fiction and the future:

Gripes, gibes, and conjectures. The Futurist, 38, 62–64.

Joels, K. M. (2004). Future studies: An interdisci-plinary vehicle for space science education. Retrieved March 24, 2005, from http://www.jsc.nasa.gov/er/seh/future.html Kipp, M. (2001). Mapping the business

innova-tion process. Strategy & Leadership, 29, 37–40. Knotts, T. L., Jones, S. C., & Udell, G. G. (2003). Small business failure: The role of management practices and product characteristics. Journal of Business & Entrepreneurship, 15, 48–63. Lach, J. (1999). Dateline America: May 1, 2025.

American Demographics, 21, 19–22. Mahaffie, J. B. (2003). Professional futurists

reflect on the state of futures studies. Foresight: The Journal of Future Studies, Strategic Think-ing, and Policy, 5, 3–4.

Masini, E. B. (1998). Futures studies from the experience of a sociologist who tries to be a futurist. The American Behavioral Scientist, 42, 340–347.

Mathews, R. (2001). Future speak. American Demographics, 23, 71–72.

McIntyre, F. S., Hite, R. E., & Rickard, M. K. (2003). Individual characteristics and creativity in the marketing classroom: Exploratory insights. Journal of Marketing Education, 25, 143–150.

Millenium Project. Retrieved June 11, 2005, from http://www.stateofthefuture.org

Miller, C. W. (2001). Meeting real needs with real products. Strategy and Leadership, 29, 15–20. Mintzberg, H., & Gosling, J. (2002). Reality

pro-gramming for MBAs. Strategy and Business, 26, 28–31.

Navin, S. L., & Burdin, J. (1986). Preparing stu-dents for the electronic cottage. School Coun-selor, 33, 253–258.

Nervy, P. L. (2004). Paul nervy notes. Retrieved July 31, 2005 from http://www.paulnervy.com/ pnn061.html

Orndoff, K. (2004). Futurism Revised. Retrieved April 12, 2005 from http://www.keith orndoff.com/futurist.html

Pashiardis, P. (1996). Environmental scanning in educational organizations: Uses, approaches, sources, and methodologies. The International Journal of Educational Management, 10, 5–9. Paul, P. (2003). 25 years of American

demograph-ics: Demographic diamonds/futurists/trend spotters. American Demographics, 25, 40–44. Peterson, R., & Pratt, E. (2004). The history

sphere in MBA marketing instruction: An application. Marketing Education Review, 14, 55–68.

Pfeffer, J., & Fong, C. T. (2002). The end of busi-ness schools? Less success than meets the eye.

Academy of Management Learning and Educa-tion, 1, 78–95.

Pinard, C., & Allio, M. (2005). Innovations in the classroom: Improving the creativity of MBA students. Strategy & Leadership, 33, 49–51. Pohl, F. (1996). Thinking about the future. The

Futurist, 30, 8–12.

Richards-Wilson, S. (2002). Changing the way MBA programs do business—lead or languish.

Journal of Education for Business, 77, 296–301.

Rodrigues, C. A. (2005). Culture as a determinant of the importance level business students place on ten teaching/learning techniques: A survey of university students. Journal of Management Development, 24, 608–621.

Sanal, R. P. (2003). An introduction to futures studies. Science India, 6, 25–31.

Schellhardt, K., & Crittenden, V. L. (2005). Spe-cialist or generalist: Views from academia and industry. Journal of Business Research, 58, 946–954.

Shays, E. M. (2003). Helping clients to control their future. Consulting to Management, 14, 48–59.

Shelton, C., Yang, J., & Qian, L. (2005). Manag-ing in an age of complexity; quantum skills for the new millennium. International Journal of Human Resource Development & Management, 5, 127–141.

Shivers-Blackwell, S. L. (2004). Reactions to out-door team building initiatives in MBA educa-tion. Journal of Management Development, 23, 614–626.

Shostak, A. B. (2000). Toffler and Rowling: Futurism and fantasy. Future Times, 11, 27–34. Singh, P., & Martin, L. R. (2004). Accelerated degree programs: Assessing student attitudes and intentions. Journal of Education for Busi-ness, 79, 299–306.

Slaughter, R. A. (2002). From forecasting and sce-narios to social construction: Changing methodological paradigms in futures studies.

Foresight: The Journal of Future Studies, Strategic Thinking, and Policy, 4, 26–31. Tomkovick, C. (2004). Innovative marketing

edu-cation. Marketing Education Review, 14, 1–2. UNESCO. (1995). The cultural dimension of

development: Towards a practical approach. Paris: Author.

Van Auken, S., & Chrysler, E. (2005). The relative value of skills, knowledge, and teaching meth-ods in explaining master of business adminis-tration (MBA) program return on investment.

Journal of Education for Business, 81, 41–45. van der Werff, T. J. (2000, April 24).

Scenario-based decision making technique. Global Future Report,1.

Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., & Austin, J. T. (2004). Cynicism about organizational change: An attribution process perspective. Psychologi-cal Reports, 34, 1421–1435.

Weiner, E., & Brown, A. (2005). A right-of-way strategy. Strategy & Leadership, 33, 21–24. Wellner, A. S. (2001). Futurespeak. Interview with R.

E. Herman. American Demographics, 23, 23–26. Wishart, A. (2000). House proud. Ideal home

show, exhibition. New Statesman, 129, 50–51. Wittmer, D. P. (2004). Business and community:

Integrating service learning in graduate busi-ness education,Journal of Business Ethics, 51, 359–372.

APPENDIX

Master of Business Administration Students’ Knowledge of Future Studies Questionnaire

Directions: Listed below are a number of statements that deal with planning in business firms. Please indicate your degree of agreement or disagreement with each of the state-ments by placing an “X” in the appropriate space.

Disagree Disagree Agree Agree Very Fairly Fairly Very Strongly Strongly Neutral Strongly Strongly

Statement 1 2 3 4 5

1. As part of the long-run planning process, managers should con-sider time periods of 20 or more years in the future.

2. If I was a manager constructing long-run plans, I would con-sider time periods of 20 or more years in the future.

3. Futurists can be useful in the formulation of managerial plans.

4. Managers can learn to become futurists.

5. Futurists’ views of the future tend to be accurate.

6. The only thing that futurists do is make forecasts.

7. Futurists use the scientific method.

8. Futurists are mainly unscientific crystal ball gazers.

9. Most managers have a favorable image of futurists.

10. Most members of the public have a favorable image of futurists.

11. Insight on futurism is available on Web sites and in magazines and journals.

12. To become an effective futurist, one must have extensive training.