What is political about political ethnography?

On the context of discovery and the normalization

of an emergent subfield

Claudio E. Benzecry1&Gianpaolo Baiocchi2

#Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2017

Abstract Despite recent interest in political ethnography, most of the reflection has been on the ethnographic aspect of the enterprise with much less emphasis on the question implicit in the first word of the couplet: What is actually political about political ethnography and how much should ethnographers pre-define it? The question is complicated because a central component of the definition of what is political is actually the struggle to define its jurisdiction and how it gets distin-guished from what it is not. In this article we aim to show how ethnography can actually lead us out of this conundrum in which the political is paradoxically both predefined and, at the same time, the open question that leads the process of inquiry. We do so by advancing a formal and relational approach that provides us with procedural tools to define the nature and specificity of the political bond not ex ante, but rather during the process of research itself. In the first part of the article we historicize the development of political ethnography as a distinct avenue for inquiry and show what have been the challenges to its normalization. This is followed by the article’s main section, which focuses on the four ways in which what is political has been conceptualized in contemporary socio-ethnographical literature. In the conclusion of the article, we advance a lowest common denominator definition proposal, with examples from other scholars as well as from our own research to illustrate how this approach would work.

* Gianpaolo Baiocchi gb97@nyu.edu

Claudio E. Benzecry

Claudio.benzecry@northwestern.edu

1

Department of Communication Studies, Northwestern University, 2240 Campus Drive, Evanston, IL 60208, USA

Keywords Conceptualization . Context of discovery . Ethnography. Politics . Sociology of knowledge

Over the last decade ethnography has gained prominence as a particular way of producing data and comprehensive explanations about areas of life usually defined as political. Scholars have celebrated how politics have been put under Bthe microscope^ and the many gains that have come with that (cf. Auyero 2006; Baiocchi and Connor 2008; Luhtakallio and Eliasoph 2014). Some have em-phasized how observing entities like the state up close and over a long period of time has produced a clearer picture of its mechanisms of operation (Lichterman 1998), as well as unraveled the causality of many of its previously described processes (Tilly 2006). In addition to edited volumes on political ethnography, journals like Qualitative Sociology or the Journal of Contemporary Ethnography have published special issues dedicated to this sub-area of study. Some scholars, like Auyero (2006) have signaled the impor-tance of studying politics ethnographically, but also indicated that despite notable exceptions, political sociology has not taken up ethnography centrally. Other authors (Baiocchi and Connor 2008) have taken a longer temporal lens and emphasized how political ethnography predates our current understanding of it, showing its roots both in anthropology and in sociological community studies. In doing this, they also called our attention to one of the main shortcomings of political ethnography: how, given the diverging standards of home disciplines of researchers, its hybrid disciplinary character has had con-sequences for the justification of theories advanced from cases that had been already framed as either sociology or anthropology.

This aticle turns to one of the silences in those discussions, namely the question of

what is actually political in political ethnography. Political sociology and political science have usually taken for granted that the object of its inquiry was formal politics, the distinction between civil society and State, associative life (especially in its intersection with social movements), and the work of political parties. Political ethnographers often make the claim that the ethnographic gaze calls into question many of the assumptions of traditional political studies and that this can call for a significant re-theorization. Unfortunately, political ethnographers have been less reflexive about what they think political life actually is, given that the field of inquiry was to a certain extent born as a challenge to more formalized versions of that question. Yet ethnographers need not take these definitions for granted and could begin to outline more deliberately the as-sumptions they are packing into abstract concepts. What is it that they call political? Why? Is it something that comes from the data? Is a predefinition in the context of investigation occluding the possibility of interrogating other phenomena? And of course, thanks to nominalist authors such as Wittgenstein (1953) and Bourdieu,1 we also know that a central component of most defini-tions of what is political is the struggle actually to define its jurisdiction and

1

how it gets distinguished from what it is not. In this article we aim to show how ethnography can actually lead us out of this conundrum in which the political is paradoxically both predefined and at the same time the open question that leads the process of inquiry.2

In the pages that follow we very briefly historicize the development of political ethnography as a distinct avenue of inquiry, before turning to an analytical section that focuses on the four main ways in which what is political has been conceptualized in contemporary socio-ethnographical literature. We conclude by aiming for a Blowest common denominator definition^ of what is political ethnography and advance a formal and relational approach that provides us with procedural tools to define the nature and specificity of the political bond not ex-ante, but rather during the process of research. We then provide a series of examples from our own research and the research of others to illustrate how this approach would work.

Politics with a small p

Political ethnography has an interdisciplinary origin and has experienced a boom since 2000. As discussed elsewhere (Baiocchi and Connor2008; Schatz2009; Luhtakallio and Eliasoph2014; Auyero2006), we can trace it back to the Manchester school of political anthropology; the tradition of community studies in sociology (what is usually called the Third Chicago School); the cultural sociology of civic and associative life (Bellah et al.2007); as well as to the work of scholars of social movements interested in practices and biographies (McAdam1990) or in frame analysis (Gamson1992; Snow and Benford 1988). We do not offer a comprehensive review of works that define themselves under this banner, as other authors have carried out such a review, but discuss some of its insights and the origins of its predicament.

Often framing their studies in contrast toBcapital-P^politics of political science and political sociology, with its focus on formal actors and delimited institutional domains, political ethnographers have claimed many advantages to their work. Ethnographic

2This last point has been central to the analysis of political philosopher Claude Lefort (1981) for whom the

studies of politics can provide an understanding of how state, national, or global actions play themselves out on local stages (Burawoy2000; Scott1986,1990). In addition,

practicesin the political realm can be examined. Questions such as how do people (not) get involved in politics can be answered by studying how individuals negotiate their actions in regards to political issues in their everyday lives (Auyero2003; Eliasoph 1998; Gutmann 2005). And in addition, political ethnographies get to the lived experiences of the political. Where previous studies of politics used broad strokes to paint a picture of political life, political ethnography allows the researcher to bring up the mundane details that can affect politics, providing a‘thick description’where one was missing. In this sense,Bpolitical ethnography provides privileged access to [the] processes, causes, and effects^of broader political processes (Tilly2006, p. 410).

And taken as a whole, the literature has developed a number of insights. First, much of the work has advanced a relational definition of politics. That is, for most of the scholarship under this banner politics are relational, they are not necessarily society-centered, but can actually arise from other parts of the social, be it the state, markets, or some in-between space, without something like the HabermasianBlife world^having a preeminence over the milieu in which the activities deemed political happen. To a certain extent a lot of research is currently taking place at what Auyero (2007) has called the Bgray zone,^ the intersection of routine, everyday, and formal politics as a hybrid area where polity, policy, and politics dissolve.

Second, the work has shown that there are no pre-conditions for when and how politics exist or arise. Unlike previous models of sociological inquiry implicitly or explicitly normative,3and thanks also to the work of comparative historical sociologists like Ikegami (2005), Casanova (1994), and Forment (2003), we know that activities usually considered as politics by scholars and laypeople have existed despite the lack of a strict separation between state and civil society. This literature has contributed to the stream of ethnographic studies of the polity by showing when activities usually considered as political have flourished in contexts that previous theories have deemed as impossible for it to happen. It has also helped combat teleological versions of the development of the political arena as a distinctive milieu of exchange and interaction, a state only possible when the influence of economic and political power is neutralized. And it has also expelled transcendental dimension implicit in the public sphere narrative, in which there is always a tension between the ideal result (the general will or the common good) versus the will of the many.

As a result of these insights, ethnographers have over time given up on dichotomies like citizen/client, in which one part of the pair was meant to be the normative guide to how to understand the other (Auyero2003). And more generally speaking, political ethnographers have moved away from the notion of the idealized individual citizen making claims before the state. Scholars have shown instead, and in many different ways, that political subjects are multiple and contradictory—client, activist, politico, voter, campaign manager, entrepreneur, protester, patron, bureaucrat, hustler, etc. Political ethnographers have opened exciting vistas to messy, real-world, Bsmall-p^ politics.

3

On the impossible normalization of an emergent field

Yet the growth and consolidation in the early 2000s of the sub-discipline has also presented it with a particular paradox. On one hand, because it has often been a literature defining itself against, and deriving analytic leverage from its difference from,

Bcapital-P politics,^it has not preoccupied itself with definitions de novo as much as differences from extant definitions. At the same time it has attempted to normalize itself and claim its jurisdiction in sociology (be it via edited issues, conferences, or the coinage of specific and particular concepts), while keeping itself open to new litera-tures, such as the pragmatic turn in cultural sociology, or Actor Network literatures in social studies of science. This, to a certain extent, has meant that all scholars have been able to be in a common conversation, while keeping the referent of that conversation sufficiently vague. While providing common terrain, the disadvantage of that ambigu-ity has been that authors often actually talk past each other because theBit^of political is something completely different. And the attempt at normalization has also had other consequences: it has, to a certain extent, pushed out of the conversation fellow travelers who have either worked on domains not explicitly labeled as political but from which similar theoretical and methodological lessons could have been taken, such as contem-poraryBurban ethnographies^(Kasinitz1992), from non-ethnographic approaches that clearly share important concerns as in comparative-historical sociology (Brubaker 2006; Ikegami 2005); or from non-sociological ethnography less concerned with defining itself as working onBpolitical^topics. (Wedeen 2008; Gutmann2005; or Li 2007).

It is for this reason, then, that we believe the exercise of more clearly defining and operationalizing the political in political ethnography is in order. The task at hand is a descriptive one; we are not making normative claims about the proper usage of the word or an ontological claim about what the political actually is. Our purpose in using a lexicographical approach (cf. Abend2008; Brubaker2002,2005), is not to settle on oneBit^but rather create some clarity as to what version of politics is being presented, advanced, and discussed by different political ethnographies. The aim is to contribute to a sociological Btrading zone^ more than settling on one definition.4A first step in developing such a trading zone is to clarify what scholars have actually meant.

The multiple meanings of the political

What exactly, constitutes,Bthe political^and what distinguishes it fromBthe social^is, of course, a complicated question with a long history in political theory that we cannot hope to cover here. Suffice it to say that political theorists variously focus on the state, conflict, power, and community in their definitions. Ethnographers, on the other hand,

4

have focused on a few main questions revolving around the nature of the political bond, such as how it is organized, and whether people invest their sense of sovereignty in other citizens and organizations, or in state institutions. They have also asked what struggles labeled as political are about, such as access to the state or accumulation of symbolic and material resources. If we examine carefully what ethnographers mean when they examine politics, we can distinguishthreedistinct ways, which we refer to as polis, demos, and elector. Each of these refers to a specific domain of activity and tends to privilege particular social locations as well as strategies for how best to study them.

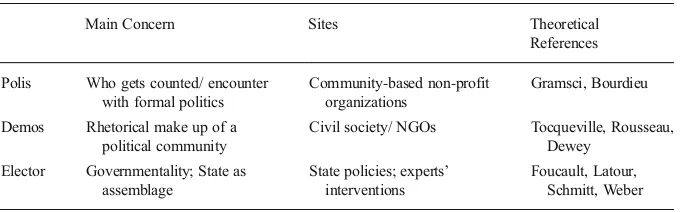

The first, which we callpolis,revolves around the question of who is counted or included in the political community. The second,demos, is concerned with the rhetor-ical make up of a politrhetor-ical community, as in the contours of its imagined communities. The third,elector,in which the political is understood as the production of subjectiv-ities, is most often associated with questions of governmentality. See Table1, which lists these types.

The question of the make-up of the polis, who is and is not counted, has been a central preoccupation for political theorists and political ethnographers have taken heed. The political lays in the encounter with formal politics, either in its routine form or in resistance or negotiation with it. The emphasis is often on showing how domination results from the struggle to uphold and reproduce the monopoly of legitimate symbolic and physical violence by the dominant groups in society. The accent is on the connections between micro settings and macro forces.

This includes ethnographies in the extended case method tradition (Lazar 2008; Thayer2001,2010) as well as works that have taken on modern versions of machine politics (Marwell2007; McQuarrie2011,2013; Pacewicz2015,2016). In both cases there is attention to how macro structural forces shape particular locales and in the role ideology/misrecognition play in hiding or naturalizing the links and forces, and how they produce practices at the meso and the micro levels. Lazar’s (2008) ethnography in El Alto, Bolivia is exemplary. Rather than paint a Manichean picture of how Western ideas of citizenship are imposed on non-Western subjects, the author aims to demon-strate that the interactions among individuals, local civic organizations, and the state create a hybrid citizenship that mirrors the hybridcholoidentity of the majority of El Alto’s inhabitants. Similarly, the work of Michael McQuarrie on the separation of community development and community organizing in Cleveland has similar concerns. The focus in this case is on theBprivatization^of community-based organizations and

Table 1 Definitions of the political

Main Concern Sites Theoretical

References

Polis Who gets counted/ encounter with formal politics

Community-based non-profit organizations

Gramsci, Bourdieu

Demos Rhetorical make up of a political community

Civil society/ NGOs Tocqueville, Rousseau, Dewey

Elector Governmentality; State as assemblage

State policies; experts’

interventions

the—sometimes—perverse effects of participating and competing within a field. Examples of this are the research on Bushwick-Williamsburg in New York by Nicole Marwell (2007); and the work of Josh Pacewicz (2015, 2016) on the adoption of partnerships by diverse organizations of union activists in aBRust Belt^city. Among the good non-US examples of this kind of research we find the work of Robert Gay (1995), who shows two alternative political strategies pursued by shantytown organi-zations in Rio.

The site for this kind of research tends to be organizations with linkages to both the world of formal policy making and urban development and to a past history of political activism. What characterizes this work is that the civic/political bond appears as non-autonomous, as always linked or intertwined with larger entities (in among State, civil society and market), and its aim is less to provide a thick description of the world within a particular community and more to point to linkages within larger fields (and to conceptualize how actions are meaningful both in the economic and the civic sphere).5 InDemos,in contrast, the locus of politics is civic life. Less directly concerned with domination, as with the examples above, the emphasis here is on the available civic spaces, and on identifying how interactions and organizations allow for certain patterns of communication or discursive styles. These allow for solidarity to arise and for those communicational styles to flourish. Also, it is far more interested in inquiring about how autonomous these spaces are from state or market intervention and what the conditions are under which—in an increasingly fragmented society—groups that cross social boundaries can actually exist and participate in producing ties within the wider community. Ethnographies of voluntary associations by scholars like Lichterman (1996, 2005) and Eliasoph (1998, 2011) are exemplars. Lichterman observes how groups produce bonds, boundaries, and speech patterns that allow or preclude for civic life to extend outside the immediate borders of the group itself, bringing a great deal of complexity to the social capital metaphor. The ethnography argues that it is not the amount of voluntary participation that matters, but rather that it is the style, which allows us to understand how long term trust can actually be developed. Mische’s relational work (2007) also belongs in here as it shows how activist-networks navigate

5Recent classics within urban ethnography have focused not on this directly but rather on its absence: the

accent is on exclusion and the retirement of formal organizations from the sphere of action of the State and civil society. Though often not labeled explicitly as political ethnography, these works deal with the political as a particular effect/consequence of the exclusion of the polis and retrenchment/retirement of the sphere of policy from the lives of the poor. Key examples of this use of political are seminal books like Philip Bourgois’s

among NGOs, parties, and the State, and allow for the public to exist in-between the civic and partisan intersection of networks. In her ethnography of youth political participation in Brazil, Mische shows the strategic importance of styles of communi-cation that result from positioning at the juncture of multiple groups. These works generally emphasize the meso level, and have a distinctive theoretical lineage; de Toqueville, Dewey, Rousseau, Arendt, and Habermas are the key theoretical coordi-nates in which these ethnographies can be located. InDemos, the political resides in the crossing among social boundaries in order to produce a collective process of deliber-ation, judgment, and action.

InElector,the political is used as a stand in for the power/knowledge syndrome, and for an analysis of the agents who decide what are the defining contours of the legitimate political community. Much of the empirical work is organized by the question of how does the state extend itself into everyday life. Most of the ethnographies conducted under this framing use the political as a way to describe how power and knowledge get articulated in productive ways that result in types of institutions, mechanisms, and subjectivities. The impetus behind this use of the political often rests on readings of Foucault and his concepts of governmentality, technologies, biopolitics, and disposi-tive. ThisBrealist^definition of the political—which includes background references to Weber and Schmitt—spans distinctive bodies of work, though, and includes work on revealing the politics of sight, under which bureaucratic power hides away that which is too repugnant to contemplate (Pachirat 2011); the work of Verdery (2002), which shows the relative autonomy of Romanian local officers in undermining private property claims; as well as more explicit ethnographies of governmentality, which scrutinize closely how state policies produce particular citizens/subjects and the inclusion/exclusion processes they generate (Decoteau 2013; Biehl 2005; Kligman 1998; Petryna2002).

Most of the authors within this kind of scholarship are political ethnographers who navigate between anthropology and sociology. Among sociologists, we deem exem-plary Auyero’s continuing line of investigation about the urban poor in Argentina (Auyero and Swistun2009; Auyero2012), in which he shows how poor populations are produced asBpatients of the State^and how they are Bmade^confused about the toxic waste they inhabit by diverse state and non-state agents, as well as the recent work of one of his disciples, Pablo Lapegna (2016), who shows the concerted work of provincial political leaders, state bureaucrats, and local social movement leaders in actively producing the de-mobilization of peasants against the toxic consequences of the soybean boom in northeast Argentina.

termedBstate legibility,^by looking at the work of local Latino promoters of the 2010 US Census and their work in making sure members of the Hispanic population allowed themselves to be accounted for by the census, as a paradoxical way of gaining visibility and consequently access to resources.

Varieties of world-making: Towards a lower common definition

of how to study the political?

Given this diversity of definitions, how can we use these words in conversation? We would like to suggest there is lower common definition that belies these various approaches. The question of what activities count as political would be much more profitably addressed if our words and concepts were clearer, and comparisons could be more profitably leveraged. We asked ourselves, after having catalogued the most salient research from the last two decades: can we aim for a lowest common denominator definition? What would it look like? What would be its analytical usage and potential contribution? In other words, what would happen if scholars went into the field armed with a set of theoretical sensibilities that would allow us to interrogate the world, imagining what concept of the political—among the myriad of existing ones—would best fit the case? This is in contrast to both thetabula rasathat grounded theory imagines as well as with the impulse towards quod erat demonstrandum more common to critical approaches, which tend to privilege one pre-established theoretical perspective, and consequently where we find only what we already know. We build up here on Timmermans and Tavory’s (2012) call for abduction in qualitative work. For them, qualitative work begins from extensive and broad knowledge of the pre-existing theories that allow for anomalies to be identified and for theory to be constructed. We are less interested here in the question of innovation but want to highlight the role that multiple theorizations play in allowing the researcher to engage in a recursive process of double fitting data and theories. Where we differ from Timmermans and Tavory, however, is that rather than calling for a more generalized theoretical multiplicity as an avenue only for theoretical innovation, we see in theBfalse^starts of the construction of the study object, not an avenue for the search of anomalies, but rather a great opportunity for the challenge of our earlier theoretical and normative pre-conceptions.6In looking at the different theories that have been mobilized to name and explain political phenomena, we pair down the frameworks related to the political as a way to generate a trading zone for political ethnography.

Our specific proposal is actor-centered. We propose beginning with the world that informants construct for themselves—by what they do, what they say, or what they say they do—and follow that through to broader dimensions, attentive to three issues central to political life:trajectories of individuation, mediation,andcategorical divi-sion.In looking at these three, we explicitly show the research choices of some of the best exemplars of the literatures we discussed in the previous section, underscoring

6

how theory and methods usually constitute a package (Clarke and Star2008), in which theory relates strongly to how ethnographers conduct research. Each dimension follow-ed by scholars also highlights one particular road for data production. In the first case, it is the collection of long term trajectories of individuals as they enter the polis via participant observation; in the second one, it is the work of reconstructing the integra-tion of individuals into organizaintegra-tions, and the history of said organizaintegra-tions within a larger ecology of competitors, via archival and interviews; in the third one, we see the focus mostly on meanings and interviews through which the subjects imagine them-selves and others.

The first question we ask concernstrajectories of individuation. What are the trajectories by which individuals construct selves that are political? Instead of thinking of the individual as a finalized and punctuated self, clearly delimited, we want to observe in which relational ways individuals inscribe themselves in groups and activities they qualify as political. Sometimes this takes place within larger holistic and hierarchical ideas of selfhood that scholars have identified.7But principally, we need to be attuned—through their activities—

to how they individuate and affiliate. In terms of the literature, for example, scholars have turned up many different kinds of political selves: volunteers, campaign managers, activists, citizens, militants, clients, hustlers,hockey moms? What are the rights and obligations implied in inhabiting each role? This way of producing data has privileged one version of qualitative work: that based on the long-term ethnographic observation of trajectories, careers, and turning points in how people learn to be part of a political self. These observations have usually occurred in fieldwork that happens over the course of many years, with several revisits, as to make sure to capture the larger context that goes beyond just the observation of interactions or situations and provides a fuller picture of the possibilities and constraints afforded by the process of individuation.

Whileindividuationrefers to the formation of political selves,mediationrefers to the main avenue through which participants establish bonds they understand as political. In some cases this question has meant looking at the question of access to problem solvers and networks that broker symbolic and material resources. In some cases the research has focused on state offices and officers as the vehicle of this bond; and in others the focus has been on organizations: NGOs, civil society, political parties, or activist networks. What all these have in common is that the organizing question is the search for the linkages among individuals, groups, and organizations in order for individuals to gain access to assets or recognition. Here the privileged data producing techniques have been three: archival work on the history of the organization being studied in relationship with other actors in society; interviews with both the brokers and those who are being mediated; and observations of pointed selected situations in which the organization (re)produces itself, mostly meetings and interactions with other actors perceived as political.

Divisionimplies the question of how informants imagine the political bond.8When they do so, whether they do it, what background symbols they deploy. By which

7

On this, see anthropologists like Dumont (1983) or Dias Duarte (1986) who make the punctuated idea of the individual one of the possible historical varieties of how subjectivity operates.

8This last point is particularly important if we are going to understand the agent

categorical divisions? Relatedly, how do these divisions come into play and become inscribed in institutions or routines? What is privileged here are the particular categories through which participants self-define their experiences and how they imagine what counts as political and what does not, as well as how these categories may be generative of forms of institutionalized inclusion and exclusion. Many of the studies mentioned here have shown how these divisions organize the political world, focusing on binaries such as: apolitical vs. apartisan; activist vs. politician; clientelism vs. citizenship; the moral vs. the political; the political vs. the partisan; community organizer vs. service provider. While these studies tend to privilege either semi-structured or ethnographic interviews in order to elicit the role of cultural structures in theimaginedmeaning of the participants’activities, often they are complemented by in situ observation.

Our minimal formula is both an epistemological and a methodological recipe, based on the study of trajectories, mediations, and categorical divisions, and the multiplicity of qualitative methodological options that need to be brought into scrutiny when we decide to focus not just on one avenue for inquiry, but rather on its combination. It proposes to combine the study of long-term trajectories, the study of linkages, the focus on the role of cultural structures, and to highlight accounts as the principal avenue for the production of data. And this is not a capricious choice, but rather the result of taking seriously post-positivist approaches to the context of discovery (Reed2011; Swedberg 2012). If the appropriate way to think about how to do research following this paradigm closely would be to think of it as the encounter between two sets of meanings: those of the ethnographer with those of the subjects whose lives are being studied (Reed2010), our proposal is that the early collection of data revolves around these three questions, with attention to what might be salient political instantiations, and helps us in deciding and adjudicating what kind of case this is and what roleBpolitics^ plays in it. This means following actors and taking their activities and understandings seriously as a first step, but it also means a great deal of agnosticism about what might be the privileged social location of political activity. If we are able to recognize the contested, reflexive, and complex character of how people think about themselves, we should be able to imagine ourselves in the same terms and be reflexive about our theoretical frameworks as the meanings we mobilize while building the study object.

To illustrate the power of this approach we draw on four examples below: a classic work on the historiography of popular protest, one contemporary ethnography, and, more presumptuously, two projects we have been involved in.9In each of the cases, following actors’own definitions of the political, while the scholars were sensitized to the three dimensions above, provided unexpected insights.

Unexpected insights and actor

’

s definitions of the political

E. P. Thompson’s (1971) analysis of paternalism not as something imposed from the top down, but rather as the preferred political repertoire of the poor, which lagging in

9Returning to past fieldwork as a source of inspiration is less common in sociology than in anthropology (e.g.,

time, had re-activated a political bond based in a previous form of political and labor control exercised by those in power, is a classic exemplar of the approach and sensibility we are aiming to highlight. His article BThe Moral Economy of the English Crowd^ questions the usual portrayal of eighteenth-century food riots as

Bspasmodic episodes^ bereft of deeper, sustained political consciousness and activity. Against an account of popular history composed of occasional social disturbances spurred by some sort of economic stimuli that caused Brebellions of the belly^—a bad harvest, unfavorable weather, trade disruptions—Thompson offers his own views based on theBmoral economy of the poor.^Thompson traces the contours of the bread-nexus during a period in history in whichBprofit^was still negatively seen by standard communal relations. Millers and bakers were seen as servants of the community and middlemen were immediately suspect characters. Underwritten by ideas of customs and rights, the paternalist model tightly controlled economic practices and relations around food. People subject to dwindling access to food began mobilizing literally to set the price of wheat or bread. As evidence of the political undercurrent of the crowds, Thompson notes that violent actions against millers rarely looted supplies: sometimes they reset the price of purchase, other times the actions were wholly punitive against profiteering, so there was a disciplining effect at work more lasting than the fleeting action itself. Occupying positions that allowed them a near-bird’s-eye view of the economy—porters, dock workers, mill workers—the poor could easily monitor move-ments and production of grain. Thompson also notes the key role of women as instigators of the revolts.

While not a political ethnography per se, Thompson’s analysis ofBfood riots^has been an inspiration for political ethnographies interested in mobilization and protest by subordinated groups and agents.10 But more importantly, it involves many of the elements we have highlighted here: the account of the actors’own self understandings goes beyond automatic explanations; the focus both on the meanings that organize actions and on key actors and activities through which the meanings are carried into particular actions; the partition of the world into moral categories and how particular actors fit in those views; and the research concludes in a way that is absolutely counterintuitive to what is expected.

Auyero’s (2001, 2003) investigations of political Bclientelism^ among the urban poor on the outskirts of Buenos Aires is another exemplar. Clientelism has long been a theme for political scientists who observed that, as an asymmetrical relationship, it perpetuates the social standing of both patron and client and is sometimes seen as something akin toBfalse consciousness.^ According to Gay (1998), clientelism has been held responsible for many of the ills in the region’s democracies;Bit is clientelism that forges relations of dependency between masses and elites. It is clientelism that stifles popular organization and protest. And it is clientelism that reduces elections to localized disputes over the distribution of spoils^(p. 7). Similarly, Auyero (2001, p. 20) describesBpolitical clientelism as one of those simplifying images that obscure more than clarify^ because so much is simplistically explained by it, from oligarchical domination to lack of organization and participation. But by observing it closely and unpacking its meanings for poor participants, something other than simple social

10

reproduction emerges. Rather, clientelism appears not as an instrumental and coercive exchange of votes and favors, but rather as an unequal exchange bond articulated relationally as a meaningful caring relationship.

The ethnography thus describes these relationships as sites for problem-solving and for the formation of political identities. The idea thatBpressing problems can be solved through personalized political mediation and that there are good [brokers] to be had^ then becomes part of the common sense of shantytown dwellers (p. 211). Active participation in this system of problem solving creates and recreates political identities

Bas much as it provides food and medicine.^These identities are constantly reinforced through ritual and material practices. Rather than presenting clientelism as the opposite of political engagement, Auyero shows how participation in these networks is deeply political. Allegiance to these ways of problem-solving creates a distinct political culture and approach to politics. But by observing it closely and unpacking its meanings for poor participants, something else emerges—Bagency and improvisation of the poor,^ strategies of survival, and problem solving.

A third ethnography we want to present as an exemplar is one of our projects: a study on how politics was experienced by actors who mediated between neighborhood organizations and formal political institutions in the northeastern city of Salvador da Bahia, Brazil (Baiocchi and Corrado2010). It emerged from the idea of understanding actually existingBpopular^civil society–that is, voluntary life among popular sectors, in Salvador da Bahia. It was based on a series of ethnographic interviews with activists about how civil society, political parties, and the State are lived and experienced in the popular neighborhoods of the city. While there is by now a burgeoning literature on Brazil that details all the existing participatory institutions that exist in cities throughout the country, state institutions that have opened up spaces for participation and overlap with civil society networks, here we begin from theBbottom^—the neighborhood, the

terreiro,or the neighborhood school and try to trace our wayBup^to the state. To our surprise, we seldom got there—not because civil society was absent or unable to do it, but because there is a profound disconnection between the life-world of neighborhoods and the logic of state institutions. This provided an unexpected insight into ethnic mobilization there. Salvador is Brazil’s Black capital and it has the country’s most visible symbols of Black culture. Yet, the city’s Black Movement has largely been unable to achieve local gains or even play a prominent role in electoral politics, which some scholars have dismissed as result of Black Brazilian’s acceptance of the myth of Racial Democracy. Yet, our research clearly showed both an awareness of racism and strong ethnic mobilization. So it was notBfalse consciousness^or lack of ethnic mobilization.

reformist political project, and added a local and political dimension to the understand-ing of race relations in Brazil.

Finally, a fourth project was on the apparent cynicism of American life (Baiocchi et al.2014). A group project on the state of civic life in the United States, it followed civil society organizations in Providence, Rhode Island over the course of a year. A central debate in the contemporary civic engagement and democracy literature concerns the apparently skeptical American citizen (Putnam 2000; Eliasoph 2011; Lee2015; Walker2014). We found that in Providence, as in America as a whole, skepticism and engagement were ubiquitous. Our fieldwork showed that individuals and groups were simultaneously skeptical of and engaged in politics. The disavowal of politics was a cultural idiom of engagement. We saw this concept in motion at both the individual level (BI am not political^) and group level (BThis is not a political organization^). The disavowal of politics was used to distinguish one’s civic activities as autonomous from the influence of the state, politicians, and political institutions. Disavowing politics involves identity work that created new boundaries between the activities in which people actively engage, and the unsavory, ambiguous, and contaminating sphere of politics. That is to say, by asserting that she Bis not political,^ an individual may distinguish her actions and self from the polluted qualities popularly associated with politics. The research showed that the disavowal of politics was productive for civic engagement—by generating taboos against politics, disavowal actually created new notions of what it means to be a good citizen that provide avenues for legitimated engagement. We concluded that distrust and cynicism about politics is not in itself a threat to democracy or an automatic prelude to disengagement. Rather, attention to the day-to-day practices and meanings of participants in civil society shows that disavowal of the political allows people to constitute creatively what they imagine to be appro-priate and desirable forms of citizenship and civic engagement.

All these accounts upend authors’ initial views of what might be considered political. The projects did not find a paternalistic labor regime for the British author, nor an unequal instrumental and depoliticizing exchange for the Argentinean scholar. In the case of Brazil, the research did not show the powerful ideology of racial democracy shaping neighborhood non-engagement, while in New England, disavowal was not a synonym of cycnism and disengagement, bur rather only one way of doing politics. In each case, attention to actors’own activities and definitions of the political within the context of labor regimes, patronage schemes, civil society organizations, or racial politics, and how these manifested in terms of individuation, mediation, and divisions powerfully shifted theoretical expectations, producing surprising accounts of political life, thanks to avoiding a formulaic pre-definition in the context of discovery.

Conclusions and implications

relations among terms and themes—Katz2002), most of them focus on reflexivity as a sensitizing tool and as a post-fact analytical tool, instead of coming to terms with our own (theoretical) preferences from the get go. Since we actively define what we deem political of the situation usually during the early hours of research, and thus during the context of discovery, is there any way for us not to predefine it normatively?

Recent work by Richard Swedberg (2012) advanced how to theorize as an activity. In his article, Swedberg sees knowing many competing theories as the key to devel-oping an instinct for how to adjudicate early on among contending claims about what the data might be about. While our article deals with the conceptualization of the political in ethnographic work, we would like to inscribe it within the epistemological conversation inaugurated by Swedberg. We imagine the resulting sensibility as one in which ethnographers go to the field using the theories as sensitizing concepts, con-ceiving of them as potential interchangeable lenses, which would allow us to interro-gate the world as we go along, imagining what theoretical concepts—among the myriad of existing ones—would best fit the case. We see this as a dialectical activity, in which certain occurrences in the field point us to their potential conceptualization or classification as a particular kind of phenomena, even if not in the realm of our

Bfavorite theory^(Burawoy1998; Eliasoph and Lichterman1999) still within alterna-tive options our colleagues in the sub-discipline have mobilized. This approach has proved fruitful for the generation of theoretical novelties (Timmermans and Tavory 2012); we are advocating for it here as a way to understand the use of theory in the early phases of qualitative studies at large.

This is of course particularly hard when discussing what counts as politics; while there are many competing definitions, in all of them we are still political beings, and as such bring baggage with us in terms of how we ethnocentrically predefine what counts as politics in a particular site (be it conflict, civic cooperation, debate, or resistance to regulation, etc.). We are not trying then to produce a definite version of the phenomena but rather to be explicit and reflexive about what we deem to be political and how other phenomena that other schools of thought define as political—but we may not—appear in our sites. What we want to highlight here is a central component to the grounded approach to the context of discovery—though not its relationship to theory at large: patiently to take the false starts, the struggles in establishing the study object during the context of discovery, as part of the knowledge enterprise, almost as a mandatory step against theoretical omni-science, and to the service of better knowing.

In doing this we are extending and systematizing the pioneer work of colleagues like Eliasoph, Mische, Lichterman, or Auyero. Scholars before us—of course—have been able to produce data as political while going beyond their initial theoretical frames well before we started doing fieldwork; we would never claim for it to be a distinctively novel contribution. What we have done instead is to produce a more systematic and comparative account of what ethnographers have calledBpolitical^ in given sites and what are the possibilities that they open up for us in terms of theoretical conceptual-ization in the context of discovery, if we think of phenomena not as a given, but as emergent possibilities made out of the encounter with multiple and parallel theoretical ways of casing them.

a third one that should be resonant within the backdrop of recent qualitative method-ological debates (Vaisey2009; Pugh2013; Lamont and Swidler2014): that during the pre-study moment, qualitative scholars might be better favored not by privileging one particular path for the collection and production of data, but rather by engaging in multiple ways; taking accounts, actions, life stories, and archival work that explain the potential contexts to make sense of what might explain what is being described, observed and analyzed. As we indicated on the previous section, the limitations about what counts as political are closely intertwined with particular avenues for data collection and production. Moreover, during the second phase of the construction of the study object—what Swedberg (2012) has called the study itself—qualitative scholars at large are probably better served by not confronting their methodological choices against one another, either highlighting the advantages of interviews versus situational and interactional participant observation; or the extra local context that might shape what we encounter as immediate versus the accounts people offer about who they are.

If conceptualizations of the political seem to be loosely attached to particular versions and takes on what counts as qualitative evidence, most of the complex ethnographies described here are at their best when combining the observation of interactions and situations, with the long-term comparison of different situations, organizations, and contexts; the long-term study of the processes and careers through which agents become individualized in particular ways with the self definitions of how agents organize their place in the world; and to all that they add archival work—even if based on secondary sources—to describe the extra local character of some of the forces that might affect the described occurrences. A self-conscious awareness of the separa-tion between pre-study and the study itself, and a recognisepara-tion of the operating definisepara-tion of the political bond that emerges, as we advocate here, should allow us to set these disparate works in dialogue with each other more easily, contributing not to the dissolution of conceptual differences, but to their variegation, formalization, and comparison. Our final hope is for this article to perform some of what it describes, serving as a bridge between multiple versions of what counts as political, how this realm been researched, and the tensions and enrichments that follows from that self-conscious encounter.

References

Abend, G. (2008). The meaning of theory.Sociological Theory, 26, 173–199. Almond, G. A., & Verba, S. (1965).The civic culture. Boston: Little Brown.

Auyero, J. (2001).Poor people politics Peronist networks and the legacy of Evita. Durham: Duke University Press.

Auyero, J. (2003).Contentious lives. Two argentine women, two protests, and the quest for recognition. Durham: Duke University Press.

Auyero, J. (2006). Introductory note to politics under the microscope: Special issue on political ethnography I.

Qualitative Sociology, 29, 257–259.

Auyero, J. (2007).Routine politics and collective violence in Argentina. The gray zone of state power. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Auyero, J. (2012).Patients of the state. Durham: Duke University Press.

Auyero, J., & Swistun, D. (2009).Flammable. Environmental suffering in an argentine shantytown. New York: Oxford University Press.

Baiocchi, G., & Connor, B. T. (2008). The ethnos in the polis: Political ethnography as a mode of inquiry.

Sociology Compass, 2(1), 139–155.

Baiocchi, G., & Corrado, L. (2010). The politics of habitus: Publics, Blackness, and Community Activism in Salvador, Brazil.Qualitative Sociology, 3, 369–388.

Baiocchi, G., Bennett, E., Cordner, A., Klein, P., & Savell, E. (2014).The civic imagination: Making a difference in American political life. Boulder, Co: Paradigm Publishers.

Bellah, R., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. M., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. (2007).Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life: With a new preface. Berkeley: University of California Press. Biehl, J. (2005).Vita. Life in a zone of social abandonment. Berkeley: University of California Press. Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1992).An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Brubaker, R. (2002).Ethnicity without groups(pp. 163–189). XLIII: Archives européennes de sociologie. Brubaker, R. (2005). The 'Diaspora' diaspora.Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28, 1–19.

Brubaker, R. (2006). Nationalist politics and everyday ethnicity in a Transylvanian town. InWith Margit Feischmidt, Jon fox, and Liana Grancea. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Burawoy, M. (1998). The extended case method.Sociological Theory, 16(1), 4–33.

Burawoy, M. (2000).Global ethnography: Forces, connections, and imaginations in a postmodern world. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Calhoun, C. (2012).The roots of radicalism: Tradition, the public sphere, and early nineteenth-century social movements. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Casanova, J. (1994).Public religions in the modern world. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Clarke, A., & Star, S. L. (2008). The social worlds framework: A theory/methods package.The Handbook of

Science & Technology Studies, 3, 113–137.

Decoteau, C. (2013).Ancestors and Antiretrovirals: The Biopolitics of HIV/AIDS in post-apartheid South Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dias Duarte, F. (1986).A Vida Nervosa nas classes trabalhadoras urbanas. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Editor. Dumont, L. (1983).Essais sur l'individualisme: Une perspective anthropologique sur l'idéologie modern.

Paris: Gallimard.

Eliasoph, N. (1998).Avoiding politics: How Americans produce apathy in everyday life. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Eliasoph, N. (2011).Making volunteers: Civic life after Welfare's end. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Eliasoph, N., & Lichterman, P. (1999). We begin with our favorite theory. Reconstructing the extended case

method.Sociological Theory, 17(2), 228–234.

Forment, C. (2003).Democracy in Latin America: Civic selfhood and public life, vol I; Mexico and Peru. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gamson, W. A. (1992).Talking politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gay, R. (1995).Popular organization and democracy in Rio De Janeiro: A tale of two favelas. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Gay, R. (1998). Rethinking Clientelism: Demands, Discourses and Practices in Contemporary Brazil.

European Review Of Latin American And Caribbean Studies, 65, 7–24.

Gutmann, M. (2005).The romance of democracy. Compliant defiance in contemporary Mexico. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Habermas, J. (1989).The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hannerz, U. (1980).Exploring the city: Inquiries toward an urban anthropology. New York: Columbia University.

Ikegami, E. (2005).Bonds of civility: Aesthetic networks and political origins of Japanese culture. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kasinitz, P. (1992).Caribbean New York: Black Immigrants and the Politics of Race. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Katz, J. (2002). From how to why. On luminous description and causal inference. Parts 1 and 2.Ethnography,

2 and 3, 443-473.

Kligman, G. (1998).The politics of duplicity: Controlling reproduction in Ceausescu's Romania. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Lamont, M., & Swidler, A. (2014). Methodological pluralism and the possibilities and limits of interviewing.

Lapegna, P. (2016). Soybeans and power. InGenetically modified crops, environmental politics, and social movements in Argentina. New York: Oxford University Press.

Latour, B. (1993).The pasteurization of France. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Latour, B. (2005).Reassembling the social. An introduction to actor-network-theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lazar, S. (2008).El Alto, rebel City: Self and citizenship in Andean Bolivia. Durham: Duke University Press. Lee, C. (2015).Do it yourself democracy. The rise of the public engagement industry. New York: Oxford

University Press.

Lefort, C. (1981).L'invention démocratique. Paris: Fayard.

Li, T. M. (2007).The will to improve: Governmentality, development, and the practice of politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

Lichterman, P. (1996).The search for political community: American activists reinventing commitment. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lichterman, P. (1998). What do movements mean?Qualitative Sociology, 2, 401–418.

Lichterman, P. (2005).Elusive togetherness: Church groups trying to bridge America’s divisions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lipset, S. (1959). Some social requisites of democracy.American Political Science Review, 53, 69–105. Luhtakallio, E., & Eliasoph, N. (2014). Ethnography of politics and political communication: Studies in

sociology and political science. In K. Kenski & K. H. Jamieson (Eds.),The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication. New York: Oxford University Press.

Marwell, N. (2007).Bargaining for Brooklyn. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. McAdam, D. (1990).Freedom summer. New York: Oxford University Press.

McQuarrie, M. (2011). Nonprofits and the reconstruction of urban governance: Housing production and community development in Cleveland, 1975-2005. In E. S. Clemens & D. Guthrie (Eds.),Politics and Partnerships: the Role of Voluntary Associations in America's Political Past and Present(pp. 237–268). Chicago: University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

McQuarrie, M. (2013). Community organizations in the foreclosure crisis: The failure of neoliberal civil society.Politics and Society, 41, 73–101.

Mische, A. (2007).Partisan publics. Communication and contention across Brazilian youth activist networks. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Mitchell, T. (1991). The limits of the state: Beyond statist approaches and their critics.The American Political Science Review, 85, 75–96.

Mitchell, T. (2002).Rule of experts: Egypt, techno-politics, modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Pacewicz, J. (2015). Playing the neoliberal game: Why community leaders left party politics to partisan activists.American Journal of Sociology, 121(3), 826–881.

Pacewicz, J. (2016).Partisans and partners: The politics of the post-Keynesian society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pachirat, T. (2011).Every twelve seconds. Industrialized slaughter and the politics of sight. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Petryna, A. (2002).Life exposed: Biological citizens after Chernobyl. Princeton: Priceton University Press. Pine, J. (2012).The art of making do in Naples. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Poletta, F. (2012). Letter from the chair: Democracy inCulture. The Newsletter of the American Sociological Association Section on Culture, 25(2), 1–4.

Pugh, A. (2013). What good are interviews for thinking about culture? Demystifying interpretive analysis.

American Journal of Cultural Sociology, 1, 1–27.

Putnam, R. (2000).Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Reed, I. (2010). Epistemology contextualized: Social-scientific knowledge in a Postpositivist era.Sociological Theory, 28, 20–39.

Reed, I. (2011).Interpretation and social knowledge: On the use of theory in the human sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rodriguez, M. (2017).Cultivating consent: Nonstate leaders and the orchestration of state legibility. Forthcoming: The American Journal of Sociology.

Sansone, L. (2003).Blackness without ethnicity: Constructing race in Brazil. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. Schatz, E. (Ed.). (2009).Political ethnography. What immersion contributes to the study of power. Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Scott, J. C. (1990).Domination and the arts of resistance: Hidden transcripts. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Scott, J. C. (1998).Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Snow, D. A., & Benford, R. D. (1988). Ideology.Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization, International Social Movement Research, 1, 197–217.

Somers, M. (1994). The narrative constitution of identity: A relational and network approach.Theory and Society, 23, 605–649.

Swedberg, R. (2012). Theorizing in sociology and social science: Turning to the context of discovery.Theory and Society, 41, 1–40.

Thayer, M. (2001). Transnational feminism: Reading Joan Scott in the Brazilian Sertao.Ethnography, 2, 243–

271.

Thayer, M. (2010).Making transnational feminism: Rural women, NGO activists, and northern donors in Brazil. New York: Routledge.

Thompson, E. P. (1971). The moral economy of the English crowd in the eighteenth century.Past and Present, 50, 76–136.

Tilly, C. (2006). Afterward: Political ethnography as art and science.Qualitative Sociology, 29, 409–412. Timmermans, S., & Tavory, I. (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to

abductive analysis.Sociological Theory, 30, 167–186.

Vaisey, S. (2009). Motivation and justification: A dual-process model of culture in action.American Journal of Sociology, 114, 1675–1715.

Verdery, K. (2002). Seeing like a mayor or, How Local Officials Obstructed Romanian Land Restitution.

Ethnography, 3, 5–33.

Walker, E. (2014).Grassroots for hire: Public Affairs Consultants in American Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wedeen, L. (2008).Peripheral visions: Publics, power and performance in Yemen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953).Philosophical investigations. New York: Macmillan.

Claudio E. Benzecryis Associate Professor of Communication Studies and Sociology (by courtesy) at Northwestern University and a sociologist interested in culture, arts, knowledge, and globalization. He is the author of the award-winning bookThe Opera Fanatic. Ethnography of an Obsession(University of Chicago Press 2011) and the co-editor ofSocial Theory Now(University of Chicago Press 2017). Benzecry is currently conducting research on knowledge, creativity, and globalization, following how a shoe is imagined, sketched, designed, developed and produced among the United States, Europe, Brazil, and China.