UDC 811.111'367.625'373.42=111 811.112.2'367.625'373.42=111 811.163.42'367.625'373.42=111 Original scientific article Received on 11.09. 2013 Accepted for publication on 23.10. 2013

Dubravka Vidakovi

ć

Erdelji

ć

Josip Juraj Strossmayer University Osijek

The polysemy of verbs expressing the concept

SIT

in English, Croatian and German

This paper presents the findings of a corpus-based research of the posture verb

SIT1 in English, Croatian and German. In line with the central tenets of cogni-tive linguistics we argue that figuracogni-tive meanings of this verb are motivated by bodily experience and grounded in image schemas such as CONTAINMENT

and GOOD-FIT2 and as such follow roughly the same paths of meaning

exten-sion in the languages under scrutiny. The results of our analysis also imply that differences noted among English, Croatian and German can partly be at-tributed to different levels of saliency of particular image schemas in the three languages (e.g. figurative extensions based on the image schema CONTAIN-MENT are much more prominent in English and German than in Croatian). We also maintain that the divergent paths of the meaning extension of verbs ex-pressing the concept SIT in English, Croatian and German can be put down to idiosyncratic features of these languages which are by analogy extended from one construction or pattern of use to another. Such processes explain why it is possible for English sit, unlike Croatian sjediti and German sitzen, to behave as a transitive verb (e.g. in sentences: sit the child on a chair, sit meat on a plate).

Key words: posture verbs; SIT; polysemy; metonymy; embodiment.

1 I use small caps to refer to the concept and italics to refer to the lemma.

2 Term taken from Newman (2002: 19) to denote good fit of an object within a container.

1. Introduction

The verb sit denotes one of three major human postures which are sitting, standing and lying, and belongs to so called cardinal posture verbs (Newman 2002) along with stand and lie. Studies of their behaviour in different and unrelated languages inform us that they have developed a wide network of different figurative mean-ings, and in some languages they have even assumed some grammatical functions, e.g. they mark progressive or habitual aspect or behave as copulas (Serra Borneto 1996; Heine and Kuteva 2007: 276–279; Kuteva 1999; Lemmens 2002, 2004, 2005, 2006; Lemmens and Perrez 2010; Newman 2001, 2002, 2009; Newman and Rice 2004; Newman and Yamaguchi 2002; Schönefeld 2006). The aim of this pa-per is to determine whether figurative meanings of verbs expressing the concept SIT in English, Croatian and German follow the same paths of meaning extension and to determine whether the differences in meaning extensions between the three lan-guages can also be attributed to some cognitive factors.

The analysis of figurative meanings of verbs expressing the concept SIT will therefore put to test the hypothesis that meaning is motivated by our bodily experi-ence and encyclopaedic. Since SIT denotes a universal bodily experiexperi-ence, we expect image schemas grounded in our concrete bodily experience to be mapped on figu-rative meanings of these verbs in the three languages analysed.

We also believe that our overall experience of the concept of sitting is also rele-vant for figurative meanings of SIT. We relate pleasant feelings with the sitting pos-ture because we assume it in order to take some rest. However if this resting takes more time than necessary, we relate sitting with inactivity, idleness and time-wasting.

1.1.

Methodology

In order to throw some light on the semantic networks of SIT in the three languages under scrutiny, I analysed 500 randomly selected examples of use of sit, sjediti and

sitzen in English, German and Croatian respectively, taken from the following cor-pora: The Corpus of Contemporary American English containing more than 425 million words equally distributed between spoken and written corpora, the Croatian National Corpus consisting of approximately 100 million words, and the Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache consisting also of more than 100 million words. Due to the difference in size the analysed corpora are not quite comparable. In or-der to compare the overall frequency of SIT in the three corpora, I normalized the total number of tokens in terms of occurrence per million words. The results are

shown in Table 1. What immediately strikes the eye is the number of occurrences of sjediti per million words in Croatian which is considerably lower than that of sit

and sitzen in English and German respectively. The analysis that follows will hope-fully shed some light on this fact.

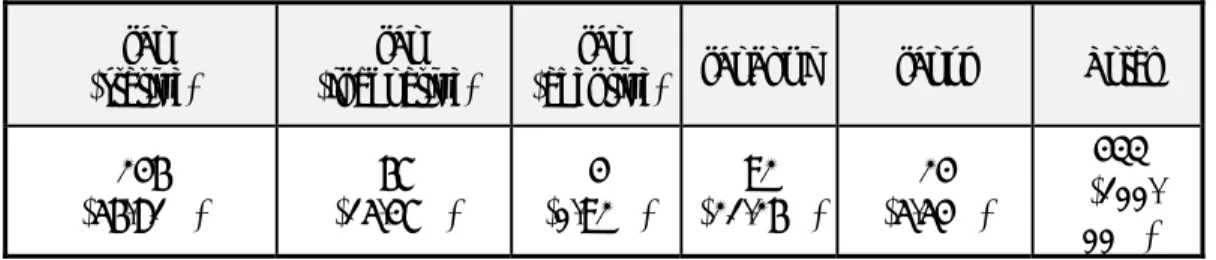

Table 1. Total number of occurrences of sit, sjediti and sitzen, and frequency per million words. Verb sit Frequency per million words sjediti Frequency per million words

sitzen Frequency per

mil-lion words SIT 158,471 372,83 5,083 50,83 32,441 324,41

The research is based on a sample of moderate size which makes my analysis qualitative rather than quantitative. However, I believe that even under such cir-cumstances it will be possible to reliably determine and compare the paths of meaning extension of these verbs in the three languages concerned. Every example of use was analysed in order to determine whether their meaning is prototypical or figurative, and to determine whether, in the case of figurative meanings, the ana-lysed languages draw motivation from the same source.

The organization of this paper is as follows. After this introduction, I will dis-cuss the lexicalisation patterns of sit, sjediti and sitzen in English, Croatian and German respectively, and then proceed with the analysis of their figurative mean-ings. In the final section of the paper I will conclude with the discussion of the similarities and differences observed in the three languages concerning the use of SIT.

2. Analysis

2.1.

Lexicalization of the event structure of sitting in English,

Croa-tian and German

According to Talmy (2000: 78) the semantic domain of states involves three as-pect-causative types: being in a state (stative aspect), entering into a state (inchoa-tive aspect) and putting into a state (agen(inchoa-tive type). All three languages analysed have different verbs for each aspect-causative type related with the experience of sitting. The stative aspect is denoted by sit, sjediti and sitzen, verbs that are the fo-cus of our research. The inchoative aspect is expressed by sit down, sjesti and sich

setzen, while the causative type is denoted by put, staviti and setzen.

Interestingly enough, our results indicated that English sit seems to be polyse-mous between stative, inchoative and agentive meanings. In order to look into this in more detail, I searched the corpus for the past tense of sit, since it is easier with this form to determine whether we have a string of events in which we have a case of sitting in its inchoative phase (e.g. I crept into my parents' bedroom and sat be-side the bed) or the continuing phase of sitting.

Although intuitively we might expect sit down (sit with particle down) to be the default choice for expressing the inchoative phase of sitting in English, the results of our analysis shown in Table 2 imply that the discrepancy between the number of appearances between inchoative sit and sit down is not that strikingly obvious (15.47 % cases of sat compared to 21.26 % cases of sat down).

Table 2. Polysemy of sit between stative, inchoative and agentive meanings.

sat

(stative)

sat

(inchoative)

sat

(agentive) sat down sat up Total 246 (56.81%) 67 (15.47%) 4 (0.92%) 92 (21.26%) 24 (5.54%) 433 (100. 00%)

When it comes to agentive sit, it is obvious from the results in Table 2 that less than 1% of total occurrences of sit are such uses. However, since this is the feature which distinguishes sit form sjediti and sitzen, I believe it merits closer attention. I searched the COCA and Google for the following strings: sit the, sit it on, in which

sit has the meaning of placing a figure on some surface.

(1) a. I sat her beside a giggling couple whom I introduced as prizewinners... b. Sit the baby on your lap …

c. You can then sit the child on a chair …

d. Sit meat on a plate to allow meat to cool for 5 minutes before slicing… e. Sit the springform tin in a roasting pan and pour in the cheesecake

fill-ing.

f. Arrange the lentils on a large dish, sit the ham-wrapped fish on top ...

g. You take the 16mm film camera and thread the camera and sit it on your shoulder.

h. While unloading groceries, sit the empty paper sacks on the floor.

i. I take the little metal box out of my jacket and sit it next to him on the bed.

j. I’d like to find a way to move that truck down the road or sit it on the sidetrack.

k. Or I've heard people who say fill the sink halfway and actually sit the plant in it,…

The examples returned (see 1 a-k) reveal that sit appears with a range of objects:

baby, child, meat, springform tin, fish, camera, paper sack, box, truck, plant. The fact that the objects of these sentences are diverse and do not share an image schema leads us to conclude that maybe here we do not have the case of meta-phoric extensions based on image schemas. I am more inclined to believe that in such uses we have the case of constructional polysemy (Goldberg 1995). The sen-tence I sit it on my bedside table at night is actually an instantiation of the construc-tion NP + verb + NP + PP.3 This construction, just like others similar to it, carries its own meaning regardless of the words that fill it in, and in this case the meaning is ‘to place an object onto a surface’. In the case of this construction the prototypi-cal verb is put, as in a sentence I put it on my bedside table at night. If we, how-ever, insert sit into the construction, the construction coerces its meaning on the verb, and sit – prototypically an intransitive verb, becomes transitive. Just like any other cognitive category, constructions also have their prototypical structure – in this case that would be the construction with the verb put, while the construction with sit stands further away from the prototype. In this construction we also have a metonymy RESULT OF ACTION FOR ACTION. Namely, the result of placing an object on a surface is that it ‘sits’ on that surface. In our example the end result of action stands for the entire action. As Radden and Kövecses (1999) point out, such me-tonymies are active in conversions and nominalizations, however in the case of NP + verb + NP + PP we only have a case of intransitive verb becoming transitive.

English is much more flexible when it comes to cases of constructional polysemy, and in particular when it comes to conversions and nominalizations, than Croatian and German are. We can thus conclude that even though meanings of posture verbs are grounded in universal and bodily experience, languages differ in the expression of that conceptual content based on already existing structures.

2.2.

Figurative meanings of

sit

in English

Compared to other two cardinal posture verbs, stand and lie, sit seems to have the least developed network of figurative meanings. This is probably due to the fact that unlike stand and lie, sit does not have a salient orientation in the physical space. In English it is used to denote sitting posture of animals if they have anat-omy similar to that of humans – with legs they can rest on:

(2) Neighborhood cats sit with backs turned.

Sit is also used to denote the position of objects (7.4% of uses) and buildings (2.6 % of uses). However, what such uses seem to convey is not the location of ob-jects but the fact that such obob-jects are somehow inactive (cf. Newman and Rice 2004: 386). Such uses seem to be more common in fiction or travel books that carry a certain amount of poetic note:

(3) a. …she ladled out the beans from a large soup tureen, which sat in the middle of the table…

b. Once it had been the hottest machine on the snow. Now it sat forlorn among the sleek new models…

c. … her slippers sat at the base of the pool with open, pink terrycloth mouths…

d. It was also empty, except for the diagnostic computer sitting against one wall.

(4) a. Mama Hallie’s shanty sits on a bayou fed by a river that floods every time it rains…

b. Above a grotto heralded as the actual site of the holy manger sits the Church

Further along these lines sit is also used to denote some kind of inactivity or resting, and even procrastination. As Newman and Rice (ibid.) also note, inactivity is an important part of its overall meaning. These meanings gave rise to the use of this verb in culinary recipes. In such uses the verb is almost invariably accompa-nied by an adverbial of time which additionally strengthens the inherent meaning of duration:

(5) a. There was a backlog of 3,000 convicted offender samples essentially sit-ting on a crime lab shelf waisit-ting to be analyzed and put into the data-base.

b. Is our mail sitting in some mail room of another company?

c. Did the White House sit on the news for three years?

(6) a. Pour the dressing into the bowl with the salad ingredients, toss well and let sit at room temperature for at least 30 minutes.

b. Allow to sit for at least 30 minutes before serving.

c. Let sit at room temperature for 15 minutes before serving.

From the preposition in that sit takes in all three languages it is obvious that the object we sit on can be construed as a container which we sit in. Lemmens (2002: 109) argues that the sense of containment is additionally strengthened by common metonymic shifts from the actual surface we sit on to larger spaces we are located in. I would add that such metonymic shifts are more informative since we are more interested in knowing that a person is sitting in the kitchen than that a person is sit-ting on a chair. These experiences give rise to two image schemas: CONTAINMENT and GOOD-FIT between figure and the ground which then serve as the basis for fur-ther meaning extensions:

(7) The keg sat perfectly in the gap between the kitchen cabinets.

This meaning is further extended towards good fitting of clothes on a person’s body. When analysing equivalent uses in Dutch, Van Oosten (1984: 154) warns that such uses should be distinguished from similar uses of stand in Dutch since the latter also express the judgment of how someone looks in certain clothes, whereas the verb sit in such uses only denotes the meaning of how clothes is fitted in terms of size and shape. Van Oosten (ibid.) believes that in such uses we have a concep-tual shift in that people are acconcep-tually those who sit comfortably in the clothes, and not the other way around:

(8) a. The dress sits beautifully over your tummy and makes you look fantastic. b. I am tall but the dress sits above my knees.

c. The jacket sits perfectly on you.

This meaning is further metaphorically mapped onto the abstract domain when we talk about the reception of news. In these cases the recipient is conceptualized as a container in which the news does or does not sit well:

(9) a. Ploener admitted that moving students around might not sit well with parents.

b. The new prestige for Niaz and did not sit well among all Shinwaris.

Sit is also very common in conventional and well-entrenched metonymies of a type PART OF SCENARIO FOR THE WHOLE SCENARIO. In such uses sit carries the meaning of ‘to be in session’ or ‘to be a member of an official body’ such as par-liament, judicial panel, councils or committees. What all these situations have in common is that people sit behind the table and carry out some other activity usually involving making important decisions. The sitting, as a prerequisite for carrying out any of those duties, is profiled as the most salient part of such scenarios, providing access to the whole scenario as a metonymic vehicle.

(10) a. She teaches, consults, sits on committees, and participates in seminars. b. Delaney, who now sits on several panels reviewing FDA regulations…

In our sample we found a total of 20 such uses which makes only 4% of the sample. This is a share considerably lower than is to be found in the other two lan-guages.

2.3.

Figurative meanings of

sjediti

in Croatian

The verb sjediti appears in its source meaning in as many as 302 examples (slightly more than 60%), while almost all remaining examples are conventional metony-mies of the type PART OF A SCENARIO FOR THE WHOLE SCENARIO (as many as 39.4 % of uses). In the sample I found only one use in which sjediti denotes the position of an object on a surface (hat on a person’s head). However, this sentence is ex-cerpted from a 19th century novel, and my guess is that this use was a product of the strong influence German was exerting on Croatian in the past due to historical conditions. Namely, uses in which German sitzen denotes the position of an object on a higher surface (just like in this one example in Croatian) are common in Ger-man, as we will see below.

I was interested in finding out whether uses in which sjediti denotes the position of objects are to be found in Croatian. Since changes in meaning are first visible in the spoken language (Tomasello 2003: 3), and since the Croatian National Corpus does not have a corpus of spoken language included, I decided to look in informal conversations one can find in different online chat rooms. Although such conversa-tions are written language, they still share some features with the spoken language (informality, slang, etc.). I found several examples in which sjediti appears with an inanimate figure.

(11) a. Čak štoviše, meni motor sjedi u garaži po dva/tri tjedna kad se vozi i sezona… ‘my motorcycle sits in my garage for two/three weeks even during the racing season…’

b. To je taj oksimoron, kupiti auto da sjedi u garaži. ‘It is an oximoron to buy a car for it to sit in a garage’

c. ziher neko ima takvu kacigu i sam mu sjedi i skuplja prašinu. ‘I’m cer-tain someone has a helmet like that which only sits and gathers dust’ Interestingly enough – these are not locational uses but uses in which sjediti de-notes inactivity and idleness based on our real-life experience of sitting. Such ex-amples are extremely rare in Croatian – to be honest, I was surprised to find them. However, the fact that some speakers of Croatian recognise the connection between sitting, a posture we assume in order to be in it for some time, and inactivity, seems to provide an ample evidence of the imprints real-life experiences leave on the way we speak.

Although I did not come across such examples in the corpus, in Croatian it is common to express the location of birds and some animals which can lean on their hind legs with sjediti. I conducted a small scale research in which 7 out of 10 sub-jects, when asked to describe a picture of a bird on a twig, used the verb sjediti.

All the remaining uses in the corpus, as many as 39.4% of them, are conven-tional metonymic expressions in which sitting as the most salient part of a scenario stands for the entire scenario. A majority of these examples are cases in which

sjediti denotes a membership in administrative bodies or control over an organiza-tion (examples in (12)). In such uses sjediti appears in a number of interesting metonymic shifts, it is possible to either zoom in or zoom out of the surface the person is sitting on without reducing the informativeness of the message. In order to state that someone is in an executive position, it is enough to say that he or she is sitting in a (e.g. Prime Minister’s) chair. On the other hand, alternative profiling is also possible in that speakers can zoom out of the scene via metonymy PLACE FOR INSTITUTION whereby a person in an executive position is conceptualized as sitting in a larger space – building or even city which for native speakers of Croatian have context-relevant meaning (e.g. in (13) Kockica – the building which is the seat of a political party, or Banski dvori – the seat of the Government).

(12) a. Osim njih, u NO-u bi trebao sjediti Krešimir Bubalo, ‘Krešimir Bubalo should sit in the managing board’ …

preds-tavnici Ministarstva zdravstva i socijalne skrbi, Ministarstva financi-ja… ‘they agreed on establishing a new task group in which the repre-sentatives of the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Finances will sit…’

c. Konstituiran je četvrti saziv Zastupničkog doma Hrvatskoga državnog sabora i u njemu će sjediti zastupnici iz 12 stranaka. ‘12 parties will sit in the House of Representatives’

(13) a. Mi znamo da njezin gazda sjedi u Kockici ‘... we know that her boss sits in Kockica’

b. Naime, radnike koji već mjesecima nisu primili plaću ne zanima previše tko će sjediti u Banskim dvorima ‘Workers who haven’t received their salary for months now, are not interested in who will sit in Banski dvori’

Furthermore, a person in an executive position normally sits at the head of the table, which is in Croatian also a rather common way of expressing that someone is in control. In these examples it is also possible to zoom out of the scene, which means that a person can sit not only at the head of the table but of an organization or even an entire country as well:

(14) a. Uprava koja sada sjedi na čelu Kombinata ima drukčije mišljenje... ‘The management now sitting at the head of the Firm has a different opinion’

b. vidljivo da na čelu Rusije sjedi jedan KGB-ovac… ‘it is obvious that a KGB member sits at the head of Russia’

Apart from such conventional metonymies expressing control, there were 2.8% of examples in the corpus in which sjediti was used to denote imprisonment. Al-though in prison one can engage in all sorts of activities, sitting again seems to be the most salient part of the imprisonment scenario, probably due to inactivity and unwelcome idleness being an inherent part of its meaning. Here again, due to ency-clopaedic knowledge of persons involved in conversation, one can again resort to the PLACE FOR INSTITUTION metonymy and zoom out of the scene (see (15b)).

(15) a. U njemačkim zatvorima sjedi više od trideset posto stranaca zbog kri-minalnih delikata. ‘More than 30 % of foreigners sit in German prisons for criminal offences…’

Yet another type of PART OF THE SCENARIO FOR THE WHOLE SCENARIO metonymy appeared in the corpus, this time in the sports terminology – sjediti na klupi ‘sit (on) the bench’. In 16 out of 21 such uses subjects were players and the entire ex-pression meant that they were in reserve, and in the remaining five cases the sub-jects were team coaches and the expression simply meant that they were coaching the team.

(16) a. Ništa ne dobivam od toga ako ću biti među 16 igračica i onda sjediti na klupi. ‘I gain nothing by being among the first 16 players only to sit on the bench’

b. Branislav Franić više neće sjediti na klupi "pivarki". ‘Branislav Franić won’t coach the team any longer…’ (literally: ‘… won’t sit on the bench of the team any longer’)

One of possible reasons why sjediti did not develop more figurative meanings probably lies in the fact that the good-fit meaning derived from the CONTAINMENT schema in Croatian is expressed by the verb sjesti, which denotes the inchoative phase of sitting as e.g. in Konačno je sve sjelo na svoje mjesto ‘Finally everything

fell in its place’; Nakon nastupa, dobro je sjeo topli čaj i krafna ‘After the

per-formance, hot tea and a doughnut felt great’ (literally, ‘hot tea and a doughnut sat down well’).

2.4.

Figurative meanings of

sitzen

in German

The analysis of randomly selected examples showed that the verb sitzen in most cases appears in its source meaning (as many as 74% of occurrences). When com-pared to two other cardinal posture verbs in German, stehen and liegen (cf. Serra Borneto 1996), its figurative meanings are few and far between. It can be used to express the posture of certain animals, primarily birds, and of those that can lean on their hind legs (cats, dogs).

(17) a. Direkt vor der Haustür saß Treff, Herrn Bruggers Jagdhund. ‘Mr. Brugger’s dog sat in front of the door’

b. Vier Spatzen sitzen auf dem Draht, ich schieße einen herunter, ... ‘Four sparrows are sitting on the line…’

In as few as seven examples sitzen is used to express the location of objects in space. Our results support Fagan (1999) in her claim that when it comes to coding location of objects with sitzen, what matters is not the orientation of those objects in space, as in the case of stehen and liegen, but rather their placement on a higher

surface.

(18) Erzbischof der Diözese, dem noch dazu die hellviolette Kalotte auf dem Kopf saß. ‘Archbishop of the diocese, who had the bright violet calotte on his head.’

The CONTAINMENT schema found its instantiation in German as well. It seems to be the motivation for coding the position of internal organs within a body with

sitzen:

(19) a. In seinem Quadratschädel sitzt ein Gehirn von der Größe eines

Atom-kerns! ‘In his square-shaped skull there is a brain the size of an atomic nucleus!’ (literally, ‘… there sits a brain…’)

b. Die zentralen Motoneurone sitzen meist auf den inneren Oberflächen

der Radialstränge und des zirkumoralen Ringes. ‘The central motor neurons are placed on the inside surface of radial strands…’ (literally, ‘… sit on the inside…’)

I also found examples in which sitzen is used to conceptualize emotions, mostly those negative ones such as fear, mistrust, shock, as physical entities placed within a container – in this case – human body.

(20) a. An solch defensiven Worten läßt sich ermessen, wie tief der Schock sitzt. ‘It is visible from such defensive words how deeply seated the shock is.’

b. Zu tief saß außerdem das gegenseitige Mißtrauen... ‘Their mutual dis-trust was deep-seated…’

The GOOD-FIT schema, a derivative of the CONTAINMENT schema is to be found in German uses of sitzen to code the proper fit of clothes on a person’s body.

(21) a. Oberhemd ist faltenlos - und glatt wie meins, es sitzt famos... ‘His shirt is uncreased – and smooth just like mine – it fits perfectly…’

b. Der dunkle Anzug, die gelbe Krawatte sitzen noch wie früh am Morgen. ‘The dark suit and the yellow tie still fit just like early in the morning.’ The seat of an organisation can also be coded by sitzen. This meaning extension seems to be based in the metonymy in which a part of the scenario of a ruler sitting on a throne stands for the entire concept of ruling. This was then mapped from the more concrete domain of humans into the domain of social organizations.

(22) a. Einer der Senate des Bundesgerichtshofs sitzt in Berlin. ‘One of the Senates of the Federal Court sits in Berlin.’

b. … denn in der globalisierten Reiseindustrie sitzen die Konkurrenten Österreichs längst nicht mehr nur in der Schweiz oder in Südtirol. ‘…because in the globalised travel industry, Austria’s competitors are no longer only in Switzerland or South Tyrol…’

Closely related to such uses are also the uses in which sitzen denotes the rule of nobility:

(23) Auf Burg Dinklage,…, wo das westfälische Uradelsgeschlecht der Galens seit über 300 Jahren saß …, war Clemens August Joseph Pius Emanuel 1878 geboren. ‘Clemens August Joseph Pius Emanuel was born in 1878 in the castle Dinklage, where the nobility of Westphalia ruled for over 300 years,…’

Sitzen is also common in conventional metonymies of a type PART OF SCENARIO FOR THE WHOLE SCENARIO, and the majority of such uses (5.6% of uses in the cor-pus) denote imprisonment.

(24) a. Da ist der alte Mann Mustapha, dessen 24jähriger Sohn verwundet im Gefängnis sitzt, ‘There is the old man Mustapha whose 24-year-old son sits in prison, injured,’

b. Getrennt von Frau und Kindern werden sie am Tage des Festes des Friedens hinter Gittern sitzen müssen, ‘Taken away from their wives and children, they had to sit behind bars during the days freedom was celebrated’

Other examples denote membership in different administrative bodies which are conceptualized as containers. Just like in Croatian it is possible to zoom in and out of such bodies from larger (Elysée-Palast) to more restricted spaces (Chefsesseln):

(25) a. Seit Jacques Chirac im Elysée-Palast sitzt,… ‘Since Jacques Chirac sits in the Elysée Palace…’

b. Freilich sitzen diese in vielen Chefsesseln des Kulturbetriebs; ‘Sure enough, they sit in many executive chairs of the Culture Department…’

3. Conclusion

From what has been said so far, it is safe to conclude that figurative meanings of SIT in English, Croatian and German are following similar paths of meaning

exten-sion. Croatian has the least developed network of figurative meanings, since, apart from meanings based on the PART OF THE SCENARIO FOR THE WHOLE SCENARIO me-tonymy, there are no other figurative meanings to be found. However, some rather rare uses of sjediti with inanimate figures show that inactivity is recognized by Croatian speakers as a relevant part of its meaning. Our corpus has also shown that speakers of English and German do not use sit and sitzen with inanimate figures for the same reasons. Namely, when used with inanimate figures sit is actually denot-ing that they are inactive or idle rather than referrdenot-ing to their actual location in physical space. This inactivity is further extended to some other context, e.g. use in culinary recipes. In English locational uses of posture verbs are not convention, in this respect English is anything like other Germanic languages (Dutch, Swedish, German) where position of objects is obligatorily coded by posture verbs (cf. Lemmens 2002, 2004, 2005, 2006; Serra Bornetto 1996). According to Kutscher and Schultze-Berndt (2007) German has 10 verbs for the expression of location of objects, e.g. liegen denotes horizontal orientation and stehen vertical. Although

sitzen is not listed among them, when referring to the position of objects in physical space, it is used with objects placed on a higher ground (possibly motivated by the fact that we usually sit on a surface elevated above the ground level). In this re-spect, sitzen is morphologically and semantically parallel with agentive setzen since it takes the same range of figures.

Motivation for other uses of sit and sitzen seems to be the CONTAINMENT schema and its derivative GOOD-FIT. Again, although drawing motivation from the common pool of universal experiences, apart from common uses (e.g. good fit of clothes), each language has also developed some specific uses, e.g. based on GOOD-FIT schema, sit is used to express reception of news, while based on the CONTAINMENT schema, sitzen denotes the position of organs within the body.

In Croatian, there are no figurative uses of sjediti based on the CONTAINMENT and GOOD-FIT schemas, since such uses are denoted by its inchoative counterpart

sjesti. This fact that sit and sitzen have more diversified uses which are partly ex-pressed by sjesti, may possibly be the reason why Croatian has the lowest fre-quency per million words of sjediti, i.e. the verb expressing the continuing phase of sitting. In its elaboration of the GOOD-FIT schema, Croatian focuses on the inchoa-tive phase of the ‘sitting of an object’ within a container. In English sit is, as our re-sults indicate (cf. Talmy 2000), polysemous between its stative, inchoative and agentive senses, which is, again the reason why it can be used to express such in-choative meanings.

Apart from the difference in the use of SIT in English, Croatian and German due to different prominence of certain schemas in individual languages, we have also noted that the divergent paths of the meaning extension of sit can be put down to idiosyncratic features of these languages which are by analogy extended from one construction or pattern of use to another. It is therefore due to the inclination to-wards conversions based on constructional polysemy in English possible for Eng-lish sit, unlike Croatian sjediti and German sitzen, to behave as a transitive verb (e.g. in sentences: sit the child on a chair, sit meat on a plate).

In the case of extensions based on the metonymy PART OF SCENARIO FOR THE WHOLE SCENARIO, our analysis indicated that they are the most common in Croa-tian. This is however not to say that they are not common in German, and English in particular, but that the corpus analysed only mirrors the diversity of the uses of

sit in the three languages. Such metonymy-based figurative extensions seem to have gained prominence in Croatian partly due to the lack of other figurative mean-ings.

In this paper, a number of important issues have been neglected and left for fu-ture investigations. Among the most interesting is the comparison of the copula-like uses of SIT in the three languages and other uses in context in which SIT has grammaticalised into the aspect marker in some other languages (cf. Newman and Rice 2004). These will hopefully be a topic of some future papers.

References

Fagan, Sarah (1991). The semantics of the positional predicates liegen/legen, sitzen/setzen, and stehen/stellen. Die Unterrichtspraxis 24: 136–145.

Goldberg, Adele E. (1995). Constructions: A Construction Grammar Approach to Argu-ment Structure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heine, Bernd, Tania Kuteva (2007). World Lexicon of Grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kuteva, Tania (1999). On sit/stand/lie auxiliation. Linguistics 37: 191–213.

Kutscher, Silvia, Eva Schultze-Berndt (2007). Why a folder lies in the basket although it is not lying: the semantics and use of German positional verbs with inanimate figures.

Linguistics 45: 983–1028.

Lemmens, Maarten (2002). The semantic network of Dutch zitten, staan, and liggen. Newman, John, ed. The Linguistics of Sitting, Standing, and Lying. Amsterdam – Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 103-139.

Lemmens, Maarten (2004). Metaphor, image schema and grammaticalisation. A cognitive lexical-semantic study. Journée d’Etudes. Grammar and figures of speech, Paris.

http://stl.recherche.univ-lille3.fr/sitespersonnels/lemmens/abstracts/abstrengposdia-chr.PDF.

Lemmens, Maarten (2005). Aspectual posture verb constructions in Dutch. Journal of Germanic Linguistics 17.3: 183–217.

Lemmens, Maarten (2006). Caused posture: Experiential patterns emerging from corpus research. Gries, Stefan Th., Anatol Stefanowitsch, eds, Corpora in Cognitive Lingui-stics: Corpus-Based Approaches to Syntax and Lexis. Berlin – New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 261–296.

Lemmens, Maarten, Julien Perrez (2010). On the use of posture verbs by French-speaking learners of Dutch: A corpus-based study. Cognitive Linguistics 21.2: 315–347. Newman, John (2001). A corpus-based study of the figure and ground in sitting, standing,

and lying constructions. Studia Anglica Posnaniensia 36: 203–216.

Newman, John (2002). A cross-linguistic overview of the posture verbs ‘sit’, ‘stand’, and ‘lie’. Newman, John, ed. The Linguistics of Sitting, Standing, and Lying. Amsterdam – Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 1–24.

Newman, John, Toshiko Yamaguchi (2002). Action and state interpretations of ‘sit’ in Japanese and English. Newman, John, ed. The Linguistics of Sitting, Standing, and Lying. Amsterdam – Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 43–59.

Newman, John (2009). English posture verbs: An experientially grounded approach. An-nual Review of Cognitive Linguistics 7: 30–58.

Newman, John, Sally Rice (2004). Patterns of usage for English SIT, STAND, and LIE: A

cognitively inspired exploration in corpus linguistics. Cognitive Linguistics 15.3: 351–396.

Radden, Günter, Zoltán Kövecses (1999). Towards a theory of metonymy. Panther, Klaus- Uwe, Günter, Radden, eds. Metonymy in Language and Thought. Amsterdam – Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 17–59.

Schönefeld, Doris (2006). From conceptualization to linguistic expression: Where lan-guages diversify. Gries, Stefan Th., Anatol Stefanowitsch, eds, Corpora in Cognitive Linguistics: Corpus-Based Approaches to Syntax and Lexis. Berlin – New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 297–344.

Serra Borneto, Carlo (1996). Liegen and stehen in German: A study in horizontality and verticality. Casad, Eugene, eds. Cognitive Linguistics in the Redwoods. Berlin: Mou-ton de Gruyter, 458–505.

Talmy, Leonard (2000). Toward a Cognitive Semantics. Vol. II: Typology and Process in Concept Structuring. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Tomasello, Michael (2003). Introduction: Some surprises for psychologists. Tomasello, Michael, ed. The New Psychology of Language, Vol. II: Cognitive and Functional Approaches to Language Structure. Mahwah, N.J.: L. Erlbaum, 1–14.

Van Oosten, Jeanne. (1984). Sitting, standing and lying in Dutch: A cognitive approach to the distribution of the verbs zitten, staan, and liggen. Oosten, Jeanne, Johan Snapper, eds. Dutch Linguistics at Berkeley. Berkeley: Dutch Studies Program, University of California at Berkeley, 137–60.

Author’s address:

Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Lorenza Jägera 9

31 000 Osijek, Croatia E-mail: dvidakovic@ffos.hr

POLISEMIJA GLAGOLA KOJI OZNAČAVAJU KONCEPT SJEDENJA U ENGLESKOM, HRVATSKOM I NJEMAČKOM JEZIKU

Ovaj rad predstavlja rezultate korpusnog istraživanja glagola koji označavaju koncept SJEDENJA u engleskom, hrvatskom i njemačkom jeziku. U skladu sa središnjim postav-kama kognitivne lingvistike, krećemo od pretpostavke da je značenje utemeljeno u tjeles-nom iskustvu te predodžbenim shemama poput one SPREMNIKA ili BLISKOG PRIANJANJA LIKA UNUTAR SPREMNIKA, pa stoga možemo očekivati da će se značenjska proširenja

ana-liziranih glagola kretati otprilike istim smjerovima. Rezultati naše analize navode nas na zaključak da se razlike u prenesenim značenjima glagola sit, sjediti i sitzen mogu dijelom pripisati različitoj istaknutosti određene sheme u pojedinom jeziku (npr. shema SPREMNIKA

istaknutija je u engleskom nego u hrvatskom i njemačkom). Također smatramo da do raz-lika u proširenim značenjima glagola sit, sjediti i sitzen može doći uslijed idiosinkratičnih osobina tih jezika koje se iz jednog uporabnog obrasca analogijom prenose u druge. Takvi procesi objašnjavaju kako je moguće da se engleski sit ponaša kao prijelazan glagol, za ra-zliku od hrvatskog sjediti ili njemačkog sitzen (npr. u rečenicama: sit the child on a chair,

sit meat on a plate).

Ključne riječi: glagoli koji izražavaju tjelesni položaj; polisemija; metonimija; utjelovlje-nost značenja.