Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 23:40

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

The Public Business School in Economic

Development: Preferences of Chamber of

Commerce Leaders

Paul Bacdayan

To cite this article: Paul Bacdayan (2002) The Public Business School in Economic Development: Preferences of Chamber of Commerce Leaders, Journal of Education for Business, 78:1, 5-10, DOI: 10.1080/08832320209599690

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320209599690

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 10

View related articles

The Public Business School in

Economic Development:

Preferences of Chamber of

Commerce Leaders

PAUL BACDAYAN

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

University

of

Massachusetts-Dartmouth Dartmouth, Massachusettsublic business schools are educa-

P

tional institutions devoted primari- ly to teaching and research. However, the mission statements at many state- funded schools also promise to assist in the community’s economic develop- ment. These promises are potentially risky. They invite the local business community to expect that schools will respond to the community’s prefer- ences, even if those preferences have relatively little to do with teaching and research. If the community is disap- pointed by the school’s contributions to the community’s economic develop- ment, the school’s credibility may suf- fer. In extreme cases, such disappoint- ment could harm the school by eroding financial support from legislators and philanthropists.In this study, I gathered data on the business community’s preferences regarding potential economic develop- ment activities that public business schools could adopt. For schools con- templating a community survey as part of the self-assessment mandated by the American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB), my results provide a preview of likely response patterns. I also offer practical suggestions for meaningful community outreach, along with suggestions for future research into faculty views and best practices at successful schools.

ABSTRACT. In this article, the author surveyed chambers of com- merce in the New England region to investigate their opinions of the role that public business schools should play in regional economic develop- ment. Although schools typically emphasize the mission elements of

research and teaching, the respondents tended to express greater interest in the capability of schools to offer tech- nical assistance and adultkontinuing education. The author offers recom-

mendations

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

for schools wishing todevelop a meaningful involvement in economic development.

Research Objectives and Background

Public business schools are, above all, schools. They naturally allocate most of their resources to teaching and research. Because resources for economic devel- opment are limited, schools may need to set priorities to focus their economic development efforts. One input for set- ting priorities is information about com- munity preferences. Accordingly, in this study I sought to quantify community preferences regarding (a) which activities schools should pursue, (b) which cliente- les schools should serve, and (c) what kinds of staff schools should provide to

carry out the work.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Choosing Activities

The local business community proba- bly does not put a premium on basic

research by professors. But how does the community regard other activities? Does applied research contribute as much to economic development as, for example, direct technical assistance? Does education for traditional students contribute as much as education for adult workers? Community perceptions, if documented, can help a school set pri- orities for economic development. Thus, I explored the following research question: “What activities do communi- ty business leaders regard as most use- ful for economic development?’

Choosing Clienteles

A school’s activities benefit different parties. For example, teaching activities often benefit traditional undergraduate students seeking to obtain a business degree before beginning their careers. But who are the most important cliente- les for economic development? The fol- lowing three possible clienteles are mentioned in literature on business schools and economic development:

adults

1. established firms and working

2. disadvantaged communities 3. emerging new industries

Helping established j r m s and workers.

Lynton (1 995) has presented the case in favor of faculty’s professional service to

September/October 2002 5

the community in the form of technical assistance. Lynton has also stressed the importance of continuing education

(Lynton, 1984; Lynton

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Elman, 1987)for maintaining the economic competi- tiveness of the workforce. Adult learn- ers, especially those seeking enhanced business skills, represent a potentially

vital part of the community.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Helping the disadvantaged. This approach is epitomized by the Metro Schools group at recent AACSB confer- ences. Composed primarily of urban schools, the members of the Metro Schools group have each focused their efforts on boosting their often-depressed communities (AACSB, 2000). Activities include technical assistance to minority businesses, applied research on policy and planning, and educational outreach to disadvantaged populations. Porter (1995) noted that urban communities have some inherent competitive advan- tages for economic development, includ- ing central location. However, such development requires support in the form of education, research, and techni- cal assistance.

Promoting new industries. Much atten-

tion has been given to special high-tech regions such as Boston’s Route 128 (Dorfman, 1983; Saxenian, 1985), Sili- con Valley (Hall & Markusen, 1985), and the Research Triangle at Raleigh- Durham-Chapel Hill. One key finding about these high-tech regions has been the importance of the agglomeration effect, or the notion that these regions require a critical mass of universities, high-tech companies, skilled labor, and companies that offer support services (Varga, 2000). Universities with indus- try links are a key element (Chmura, 1987), and business schools could, in theory, play a supporting role in the agglomeration process. Faculty mem- bers could conduct applied research that informs policy decisions. Continuing education programs might focus on boosting the technical sophistication of the area workforce. And in the realm of technical assistance, the schools could help firms that commercialize universi- ty-originated technology (perhaps in conjunction with university-affiliated

business incubators). Small firms in par-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ticular might be targeted; evidence has been found that university research spending benefits smaller firms more than large ones (Acs, Audretsch, &

Feldman, 1994; Link & Rees, 1990). If a school decides to focus its eco- nomic development efforts, it would benefit from knowing which clienteles the business community regards as most important for economic development. Thus, I formulated another research question: “What priority do community business leaders attach to the needs of traditional students, adult learners, established businesses, new industries, and disadvantaged populations?’

Choosing a StafJing Approach

Regardless of which activities and clienteles a school emphasizes, imple- mentation requires staffing. Because fac- ulty time is limited, the school may sup- plement its faculty members with specialists who focus exclusively on adult education, applied research, or technical assistance. The staffing issue presents schools with yet another impor- tant choice, which led to my final research question: “Do faculty members need to render all services, or can schools outsource certain development activities by using nonfaculty individuals?’

Research instrumentation and Method

I surveyed local business stakehold- ers to obtain their views on this issue. The survey respondents were the heads of chambers of commerce and the direc- tors of Economic Development Organi- zations. By virtue of their positions, these respondents had informed views regarding the usefulness of various ini- tiatives for business development. Both groups also represented the kinds of stakeholders that a school might turn to when assessing its effectiveness at con- tributing to economic development.

Survey Description and Sample

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I originally developed the survey

items through discussions with five deans, each of whom had led a public business school’s efforts in local eco- nomic development. The discussions

identified major possible ways for schools to become involved in local economic development (e.g., training the existing workforce), along with obstacles to school involvement (e.g., attracting faculty involvement).

The survey items described possible business school activities related to eco- nomic development. Respondents used 7-point Likert-type response scales to rate the usefulness or acceptability of each item from the standpoint of eco- nomic development. After pilot-testing the survey for clarity by administering it to a dozen colleagues and local business owners, I made revisions; the final ver-

sion took approximately 5 minutes to complete. In a cover letter, I asked recipients to draw on their understand- ing of the local business environment in their rating of the usefulness of various activities.

The survey mailing list consisted of over 400 organizations listed in the New England region of the 2001 Chamber of Commerce directory (Worldwide Cham-

ber of Commerce Directory, 2001). I

selected the New England region because it includes the state where my university is located. I sent an initial mailing in October 2001 and a follow- up mailing around Thanksgiving. Excluding those surveys returned as undeliverable, 405 organizations received a survey. Usable responses totaled 142, yielding a response rate of 35.1 %. In Table 1, I give the number of respondents for each state in the New England region. I found only minor dif- ferences between chamber of commerce respondents and economic development organization respondents, so I report their responses together. No significant

TABLE 1. Respondents by State

No. of Response

State respondents rate (%)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

CT 19 21

MA 36 32

ME 33 41

NH 23 33

RI 12 44

VT 19 36

Total 142 35

demographic differences were found between respondents and nonrespon- dents. Fifty-eight percent of the individ- uals on the mailing list were men, and 42% were women; the respondent sam- ple was 63% men and 37% women. Through a chi-square test, I found that these percentages were not significantly

different

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

0, =zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

.14). The average size of anonresponding Chamber was 498 mem- bers, whereas the sample reported an average membership of 509. I per-

formed a

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

t test (independent samples, 2-tailed,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

p = .35) and found that this dif-ference was not significant.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Findings

Preferred Activities

[image:4.612.226.564.219.584.2]Respondents were presented with 11 potential school activities and were asked to rate how much each activity would help their local economy. In Table 2, I show the individual activities grouped into the categories of technical assistance, teaching, and research. It should be noted that the respondents gave generally favorable ratings (5 or above on a 7-point scale) to most of the activities. Given that almost all activi- ties were viewed as more than “some- what useful,” the challenge was to iden- tify which of the 11 items stood out significantly in terms of desirability.

The technical assistance items received the highest average rating (5.62, with 7 representing very helpful). The teaching items received the next highest rating, with an average rating of 5.42. The research items received the lowest ratings, with an average of 4.82. Statistically, five activities stood out as top priorities. These included all three items for technical assistance and the two adult education items. The two activities that stood out as having the lowest priority were applied research on

the needs

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of disadvantaged populationsand basic research for an audience of fellow scholars.

I determined the statistical signifi- cance of differences among the ratings through hypothesis testing. For each of the 11 activities, the null hypothesis (H,) was that the average rating equals the grand mean for all of the items (5.26). I used the grand mean as the null

hypothesis to determine which activities stood out from the rest. In Table 2, a t statistic larger than k1.96 indicates that the activity was different from the grand mean at p I .05.

Preferred Clienteles

The respondents assigned top priori- ty to three groups of clients: working adults, new industries, and existing businesses. The lowest priority group

was “fellow scholars,” who benefit from basic research conducted by a school’s faculty members. The remain- ing groups’ ratings were not signifi- cantly different from the overall mean of 5.15. In Table 3, I compare measures of usefulness for seven possible client groups. The measures in Table 3 were based on the items previously present- ed in Table 2. For example, I calculat- ed the measure for “working adults” by averaging the ratings for degree pro-

TABLE 2. Respondent Ratings of Activities ( N

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

= 142)Activity M t a

Technical assistance items

Technical aid to new businesses, including start-ups 5.73 4.67*

Technical aid to underserved businessesb 5.51 2.54*

Technical aid to existing businesses 5.62 3.59*

Average for all “service” items Teaching-related items

Degree programs (BNMBA) to existing adult workforce 5.70 4.95*

Nondegree training (professional skills) to existing workers 5.57 3.04*

Degree programs to underserved andor disadvantaged

populationsb 5.26 0.05

Degree programs to new graduates (entry level) 5.16 -0.94

Average for all “teaching” items 5.42

Research-related items

Applied research benefiting new firmshndustries 5.46 1.80

Applied research on problems of well-established local firms 5.34 0.78

Applied research on needs of disadvantaged populationsb 4.69 4 . 9 2 ”

Basic research for an audience of fellow scholars 3.80 -13.01*

Average for all “research” items 4.82

5.26

Grand mean (average of items 1 through 11)

a2-tailed test, H,: mean for item equals grand mean of 5.26. Items were rated on a 7-point scale, with 7 = most useful. bllnderserved businesses are defined as firms not adequately served by private sec- tor consultants, including small businesses. Disadvantaged populations are defined as those not ade- quately served by private colleges, including low-income, minority, or first-generation college stu- dents.

*Significantly different from the grand mean at p

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I .05.TABLE 3. Respondent Ratings of Clienteles

Clientele Itemsa M f b

Working adults in current workforce

New industrylbusinesses

Existing businesses

Underserveddisadvantaged students Traditional students

Underserveddisadvantaged businesses Other scholars

Grand mean, all clienteles

4 , 5 5.64

1, 8 5.59

2 , 9 5.48

6 5.26

7 5.16

3, 10 5.10

11 3.80 -

5.15

6.12* 4.94* 3.89* 1.13 0.10 -.49 12.02*

aThese item(s) from Table 2 were used to calculate the clientele’s rating. b2-tailed test, H,: mean for item equals grand mean of 5.15.

*Significantly different from the grand mean at p I .05.

September/October 2002 7

grams and nondegree programs that

serve working adults.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

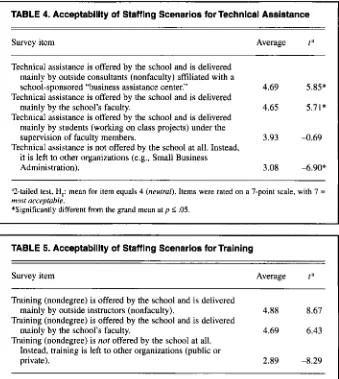

Preferred Stafing Approaches

Outsourcing is generally acceptable for the provision of both (a) technical assistance and (b) nondegree adult edu- cation. The use of nonfaculty staff can allow a school to provide outreach while still buffering its regular faculty.

The respondents, on average, stated that they would object if public business schools were not involved at all in tech-

nical assistance (rating =

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

3.08; see Table4). In cases in which schools provide technical assistance, the respondents indicated that they would not distinguish between faculty and nonfaculty pro- viders. These results suggest that schools have the option of outsourcing technical assistance to nonfaculty experts. Stu- dents, however, provide only a weak sub- stitute for faculty assistance. It should be noted that technical assistance provided by students under faculty supervision

was rated only

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

3.93. Hypothesis testingshowed that three of the four items were

significantly different from neutral (i.e.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

4,

the scale’s midpoint).The respondents viewed nondegree training-for example, evening skill development seminars for adults in the workforce-as an important school activity. The idea that schools might nut be involved in such workforce develop- ment was rejected, with a very low acceptability rating of 2.89 (see Table 5). Hypothesis testing showed that the ratings for all three items were signifi-

cantly different from neutral (i.e., 4).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Discussion and Recommendations

It might seem harmless to include economic development in the mission of a public business school. However, the challenge lies in delivering aid that is meaningful to the community itself, particularly when the community reads its own wishes into the school’s promis- es. Through our survey, we attempted to quantify the preferences of local busi- ness leaders regarding the role of public business schools in economic develop- ment. The respondents appear to have had no quarrel with traditional educa-

8 Journal of Education for Business

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

tion and research-what they really wanted from schools was technical assistance, adult education, and help with building new industries. In a sense, they appeared to prefer activities that boost business profits and growth most directly. These findings may not over- turn prevailing assumptions about what the business community wants. The findings do, however, document a seri- ous gap between typical school priori- ties and those of the business communi- ty. This gap challenges schools and their faculty members to take positive action. Thus, I sought to identify (a) practical suggestions for addressing community preferences and (b) future research needs.

Practical Suggestions fur Handling a

Genuine Risk

The results of my study indicate that a substantial “expectations gap” exists

between what schools offer and what the community wants. Schools tend to emphasize research and teaching, yet the respondents want more than that. For example, respondents found it frankly unacceptable for schools not to offer technical assistance. Similarly, respondents flatly rejected the possibili- ty of schools’ not contributing to contin- uing/adult education (professional skill development for the existing work- force). For schools attempting to work seriously to reduce an expectations gap, I formulated five practical approaches that might be useful. Because schools tend to evolve incrementally, I present

those approaches in ascending order by lead time (i.e., the first ones can be ini- tiated more quickly):

1. Communicate proactively with business. A school’s leaders can seek to

manage expectations in the business community. This approach would

____ ~~

TABLE 4. Acceptability of Staffing Scenarios for Technical Assistance

Survey item Average t“

Technical assistance is offered by the school and is delivered mainly by outside consultants (nonfaculty) affiliated with a

school-sponsored “business assistance center.” 4.69

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5.85”Technical assistance is offered by the school and is delivered

mainly by the school’s faculty. 4.65 5.71*

Technical assistance is offered by the school and is delivered mainly by students (working on class projects) under the

supervision of faculty members. 3.93 -0.69

Technical assistance is not offered by the school at all. Instead,

it is left to other organizations (e.g., Small Business

Administration). 3.08 -6.90*

a2-tailed test, H,: mean for item equals 4 (neutral). Items were rated on a 7-point scale, with 7 =

most acceptable.

[image:5.612.227.566.332.711.2]*Significantly different from the grand mean at p I .05.

TABLE 5. Acceptability of Stafflng Scenarios for Training

Survey item Average t n

Training (nondegree) is offered by the school and is delivered Training (nondegree) is offered by the school and is delivered

Training (nondegree) is not offered by the school at all.

mainly by outside instructors (nonfaculty). 4.88 8.67

mainly by the school’s faculty. 4.69 6.43

Instead, training is left to other organizations (public or

private). 2.89 -8.29

I

”-tailed test, H,: mean for item equals 4 (neutral). Items were rated on a 7-point scale, with 7 =

most acceptable.

explain how the school views its contri- butions to economic development, rather than leaving that interpretation up to the community. For example, schools can argue that students represent the school’s best long-term contribution to the economy (Hoy, 1994). This argu- ment emphasizes the school’s teaching mission and links it with the goal of economic development.

2. Cooperate with specialized agen- cies and schools. Technical assistance and adult education may already be available in a community. Rather than duplicating the efforts of other institu- tions, a business school might rely in some cases on referrals or joint projects. For example, local community colleges may already be active in providing spe- cial programs geared to the needs of working adults, and many state govern- ments have set up specialized agencies for workforce development, small busi- ness assistance, and economic develop- ment (e.g., the Massachusetts Office of Economic Development). Similarly, the federal government’s Small Business Administration supports a network of Small Business Development Centers

(SBDCs).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

3. Explore outside staffing for non-

core activities. As noted above, respon- dents flatly rejected the idea that a school should have no involvement whatsoever in adult education or techni- cal assistance. Happily, my findings also indicate that schools have flexibili- ty in how they staff the delivery of these services. The respondents are quite accepting of outsourcing, which buffers the school’s faculty. Outsourcing could be accomplished with the help of user fees (tuition for adult education), spe- cial grants, or state funding earmarked for workforce development.

4. Link the classroom to the communi- ty. Activities can include student field projects in which students serve as con- sultants under the instructor’s supervi-

sion (Roebuck

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Brawley, 1996). Itshould be noted, however, that respon- dents rated student-delivered aid as less desirable than faculty-delivered aid. Fur- ther activities might include case studies on area firms, industry notes related to the local economy, and cooperative/ internship placements. These activities may ultimately enrich the local work-

force by encouraging students to stay in

the area after graduation.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 . Encourage mission-related intel- lectual contributions. Planning and pol- icy studies seem like a natural applica- tion of a school’s intellectual resources. Accordingly, individual faculty mem- bers might conduct research on region- ally relevant policy issues or industries (Georgianna, 2000; Howard & Herre- mans, 1988). This approach must, of course, work within the school’s reward system. The challenge of measuring intellectual contributions in terms of support for the school’s mission has been discussed in Graeff (1999) and in

Einstein and Bacdayan (2001).

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Future Research Needs

To help schools implement develop- ment-oriented missions, future researchers should explore how faculty members and schools view economic development. For example, research about individual faculty preferences would be useful. Since publication of the Foundation Reports of the late 1950s (Gordon & Howell, 1959; Pier- son, 1959), advancement for business professors has been closely linked to research productivity. The AACSB’s new flexibility in allowing schools to define unique missions (AACSB, 1994) has created an opportunity for individ- ual schools to once again emphasize certain areas such as community out- reach. However, the academic reward system may present a serious obstacle to faculty involvement (Boyer, 1990). Maskooki and Raghunandan (1998) found that finance departments offered virtually no rewards for industry involvement, despite calls within the academic finance community for more faculty involvement with practitioners. Research is needed to help identify the faculty’s level of interest in various development activities and the potential impact of various inducements.

At the school level, future researchers could explore best practices at schools that have successfully balanced their mission activities. Researchers could investigate how schools set priorities, involve faculty, and provide nonfaculty staff how schools assess their effective- ness in fulfilling their economic devel-

opment mission; and whether some schools create synergies by integrating

development with teaching or research.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Conclusion

The results of

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

this study show thatlocal business stakeholders would prefer that schools allocate resources to techni- cal assistance and adult education. Given that most AACSB-accredited schools have limited resources for community outreach, school leaders must be selec- tive about their investments in economic development. A public business school cannot be all things to all people. At a minimum, school leaders may need to communicate proactively with the com- munity to manage expectations and raise awareness of the school’s actual contri- butions to economic development. Should the school launch additional ini- tiatives, those in charge should document the community’s top priorities to focus and match the school’s resources with the community’s aims.

We may never be able to prevent schools from being caught between the demands of traditional academic con- cerns and the desires of local business. But given the potentially serious discrep- ancy between schools’ efforts and the preferences of the business community, it is important for public schools to take stock of their relations with the commu- nity and take positive action to maintain the schoolxommunity connection.

REFERENCES

American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (1994). Standards for busi-

ness and accounting accreditation. St. Louis, MO: Author.

American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2000). Business schools bring management expertise to economically distressed communities. AACSB Newsline,

Acs, Z. J., Audretsch, D. B., & Feldman, M.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

P.(1994). R&D spillovers and recipient

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

firm size.The Review of Economics and Statistics, 76, pp.

336-340.

Boyer, E. L. (1990). Scholarship reconsidered:

Priorities

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of the professoriate. Princeton, NJ: The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancementof Teaching.

Chmura, T. J. (1987). The higher education-eco- nomic development connection: Emerging roles for universities. Commentary, Fall, pp.

Dorfman, N. S . (1983). Route 128: The develop- ment of a regional high technology economy.

Research Policy, 12, 299-316.

Einstein, W. O., & Bacdayan, P. (2001). Develop- 29(3), 1-5.

11-17.

September/October 2002 9

ing mission-driven faculty performance stan-

dards. Journal of the Academy of Business Edu-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

cation, 2, 9-17.Georgianna, D. (2000). The Massachusetts marine

economy: Economic development. Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Donahue Institute.

Gordon, R. A.,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Howell,zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

J . E. (1959). Highereducation for business. New York: Columbia

University

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Press.Graeff, T. R. (1999). Measuring intellectual con- tributions for achieving the mission of the col- lege of business. Journal of Education for

Business, 75(2),

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

108-1 15. Hall, P., & Markusen, A. (Eds.). (1985). Siliconlandscapes. Boston: Allen and Unwin. Howard, D. G., & Herremans, I. M . (1988).

Sources of assistance for small business

exporters: Advice from successful firms.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Jour-nal of Small Business Management,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

26, 48-54.Hoy. J. C. (1994). Coin of the realm: Students are the key to New England's economy. Connec-

tion: New England's Journal of Higher Educa- tion and Economic Development, 9(1), 10-12.

Link, A. N., & Rees, J. (1990). Firm size, univer- sity basic research, and the returns to R&D.

Small Business Economics,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2( I), 25-32. Lynton, E. A, (1995). Making the case for profes-sional service. Washington, DC: American Association for Higher Education.

Lynton. E. A. (1984) The missing connection

between business and the universities. New

York Macmillan.

Lynton, E. A., & Elman, S. E. (1987). New prior-

ities for the university. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.

Maskooki, K., & Raghunandan, K. (1998). Finance faculty evaluations and AACSB rec- ommendations. Journal of Education f o r Busi-

ness, 74(3), 11-15.

Pierson, E C. (1959). The education of American

businessmen. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Porter, M. (1995) The competitive advantage of the inner city. Harvard Business Review, May/June, pp. 55-71,

Roebuck, D. B., & Brawley, D. E. (1996). Forging links between the academic and business com- munities. Journal of Education for Business,

7/(3), 126-128.

Saxenian, A. (1985). Silicon Valley and Route 128: Regional prototypes or historical excep- tions? In M. Castells (Ed.), High technology,

space, and society (pp. 91-105). London: Sage. Varga, A. (2000). Local academic knowledge transfers and the concentration of economic activity. Journal of Regional Science, 40(2),

289-309.

Worldwide Chamber of Commerce Directory. (2001). Worldwide Chamber of Commerce

Directory: June 2001. Loveland, CO: Author.

JOURNAL OF

EDUCATION

FOR

BUSINESS

W.. ..I ..W W..

...

W D W .B....

.

.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

c]I

YES!

1 would like to order a one-year subscription to the Journal of Education.

for Business published bi-monthly. I understand payment can be made to HeldrefPublications or charged to my VISAMasterCard (circle one).

.

a

$47.00 Individuals.

.

ACCOUNT # EXPIRATION DATE

ORDER FORM

.

a

$80.00 InstitutionsSIGNATURE

.

NAME/INSTITUTION.

.

ADDRESS.

COUNTRY.

CITY/STATE/ZI P.

.

ADD $16.00 FOR POSTAGE OUTSIDE THE US. ALLOW 6 WEEKS FOR DELIVERY OF FIRST ISSUE.

SEND ORDER FORM AND PAYMENT TO:

.

.

.

.

HELDREF PUBLICATIONS, Journal of Education for Business

1319 EIGHTEENTH ST., NW, WASHINGTON, DC 20036-1802 PHONE (202) 296-6267 FAX (202) 293-6130

SUBSCRIPTION ORDERS 1(800)365-9753, www.heldref.org

.

The Journal of Education for Business readership includes instructors, supervi-

sors, and administrators at the secondary, post- secondary, and collegiate levels. The Journal features basic and applied research- based articles in accounting, communications, economics, finance, information sys-

tems, management, market- ing, and other business dis- ciplines. Articles report or share successful innovations, propose theoretical formula- tions, or advocate positions on important controversial issues and are selected on a blind, peer-reviewed basis.