Melissa S. Kearney is an Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Maryland and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. Phillip B. Levine is the A. Barton Hepburn and Catherine Koman Professor of Economics at Wellesley College and a Research Associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research. The authors thank Liz Ananat and Serkan Ozbeklik for comments on an earlier version. They also acknowledge helpful comments from seminar participants at the Harris School at the University of Chicago, the Harvard Labor Workshop, Middlebury College, the Maryland Population Research Center, University of British Columbia, Wharton, University of Wisconsin IRP, Northwestern IPR, and participants at the conferences, “Public Policy and the Economics of Fertility” at Mount Holyoke and “Labor Markets, Children, and Families” at the University of Stavanger. They thank Erin Moody and Lisa Dettling for very capable research assistance. They are grateful to Christopher Rogers at the National Center for Health Statistics for facilitating access to confi dential data. These data are available from the National Center for Health Statistics. The authors can guide other scholars wishing to acquire the data. For assistance, please contact Phillip B. Levine, Wellesley College, 106 Central Street, Wellesley, MA 02481, plevine@wellesley .edu.

[Submitted January 2012; accepted December 2012]

ISSN 0022- 166X E- ISSN 1548- 8004 © 2014 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

T H E J O U R N A L O F H U M A N R E S O U R C E S • 49 • 1

Nonmarital Childbearing

Melissa S. Kearney

Phillip B. Levine

A B S T R A C T

Using individual- level data from the United States, we empirically investigate the role of lower- tail income inequality in determining rates of early nonmarital childbearing among low socioeconomic status (SES) women. We present robust evidence that young low- SES women are more likely to have a nonmarital birth when they live in places with larger lower- tail income inequality, all else held constant. We calculate that differences in the level of inequality are able to explain a sizeable share of the geographic variation in teen fertility rates. We propose a model of adolescent decision- making that facilitates the interpretation of our results.

I. Introduction

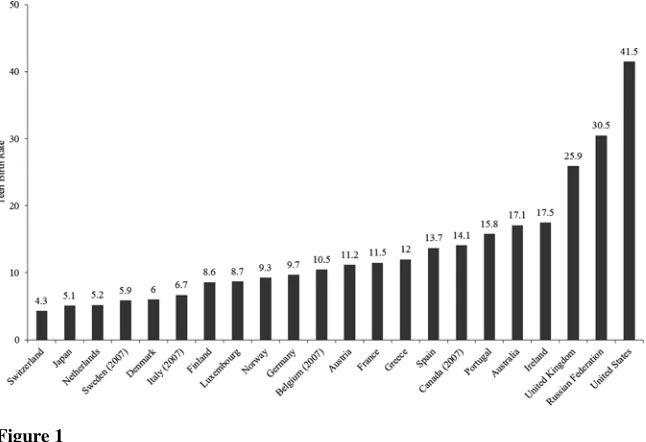

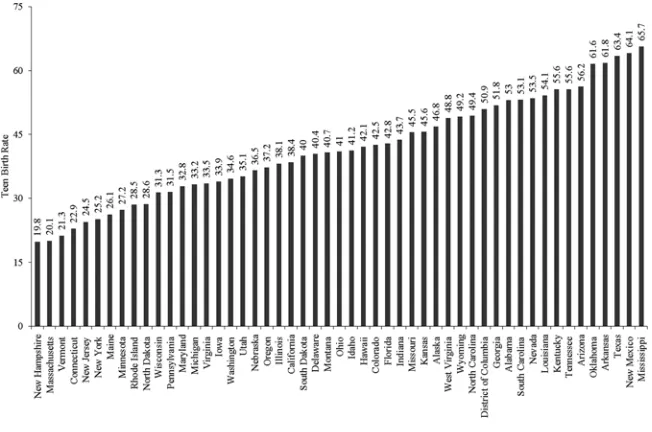

41.5 per 1,000 females age 15–19 in the United States is a multiple of the level that ex-ists in other developed countries. For example, the rate is 25.9 in the United Kingdom, 14.1 in Canada, and 4.3 in Switzerland. Figure 2 shows that tremendous variation exists across states as well. Some states have rates that are comparable to those in other devel-oped countries, but others have extremely high rates. For example, the rates in Texas, New Mexico, and Mississippi (over 60 per 1,000) are more than three times the rates in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Vermont.1 Why is it that teenagers in the United

States are so much more likely than their counterparts in other countries to give birth when young and unmarried? Why are teens in some parts of the United States so much more likely to have a teen birth than their counterparts in other parts of the country?

We consider these geographic patterns to pose both a challenge and a potential clue to understanding the determinants of early nonmarital childbearing. Year- to- year and even decade- to- decade, the states that have relatively high rates of teen childbear-ing remain the high teen childbearchildbear-ing states, and the states that have relatively low rates of teen childbearing remain the low teen childbearing states. The teen population weighted correlation between the 1980 and 2010 teen childbearing rate—averaged across states—is 0.74.

1. This cross- state variation in teen birth rates does not simply refl ect cross- state variation in overall birth rates. The highest birth rates to women age 15–44 are found in Alaska, Idaho, and Utah, which rank 35, 28, and 19, respectively, in terms of teen birth rates (Martin et al. 2010). In addition, this cross- section variation is substantially larger than recent time- series variation, which has garnered so much attention. Between 1991 and 2008, the national teen birth rate fell from a peak of 62 to 42.

Figure 1

International Comparison of Teen Birth Rates, 2008

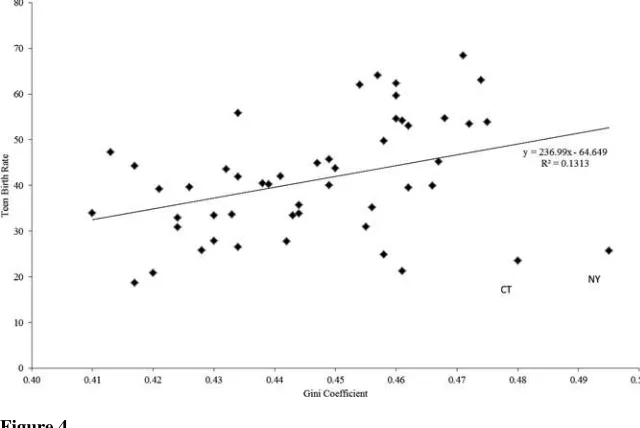

These patterns suggest that longstanding differences across states are critical. What are the persistent conditions of states that drive the decisions of young women in this regard? One potential culprit among many is income inequality, which tends to be fairly persistent within a place and shows a strong correlation with rates of early nonmarital childbearing. Figures 3 and 4 display the sizable, positive correlation between income inequality and teen childbearing across developed countries and across states.2 This

cor-relation is noteworthy, but it does not necessarily imply a causal positive cor-relationship. Various theories exist for why income inequality, as distinct from absolute income, might affect individual- level behavior.3 Social scientists, particularly political

scien-tists and sociologists, have emphasized the role of relative, as distinct from absolute

deprivation—in leading to acts of social unrest. In an economics paper on the issue, Luttmer (2005) documents that people are less happy when they live around people who are richer than themselves. Watson and McLanahan (2011) present evidence that relative income matters for the marriage decision of low- income men.4 They

inter-pret their model within the idea of an identity construct, whereby low- income men

2. Similar fi gures appear in Wilkinson and Pickett (2009).

3. Mayer (2001) provides a thoughtful review of these and other explanations in her paper on income in-equality and educational attainment.

4. Loughran (2002) and Gould and Passerman (2003) consider the effect of male wage inequality on the mar-riage decisions of women within a search model framework whereby women search for husbands based on male wages. Both papers use data from the 1970, 1980, and 1990 U.S. Census samples. Loughran (2002) tests whether changes in male wage inequality within geographically, racially, and educationally defi ned marriage

Figure 2

Variation in Teen Birth Rates Across States, 2008

Figure 3

Income Inequality and Teen Birth Rates Across Countries

Sources: Gini Coeffi cient—United Nations (2009). Teen Birth Rate—United Nations (2008)

Figure 4

Income Inequality and Teen Birth Rates Across States

postpone marriage with the goal of waiting until they achieve a higher economic sta-tus, and that status is determined by a peer reference group. Another possible mech-anism through which income inequality affects outcomes is through the effects of segregation.5 To the extent that greater levels of income inequality are associated with

increased levels of residential and institutional segregation, individuals at the bottom of the income distribution might feel a heightened sense of social marginalization, which links to the theories of Wilson (1987) and relates to the model we propose.

We propose an additional mechanism that is contextually specifi c through which income inequality might affect teen childbearing rates. A girl who views herself as having little to lose by having a baby when young and unmarried is more likely to make that choice, rather than choosing to delay. If feelings of economic hopelessness among the poor are heightened by greater disparities in income, leading economically disadvantaged young women to view the opportunity costs of early childbearing as suffi ciently low, then this could generate a causal link between income inequality and rates of early nonmarital childbearing. This idea draws heavily on the existing ethno-graphic and sociological literature on the topic, including the work of Clark (1965), Lewis (1969), Wilson (1987), and Edin and Kefalas (2005), among others. These ideas motivate our empirical analysis.

To empirically investigate whether the observed aggregate relationship between income inequality and teen childbearing holds at the individual level, we conduct an empirical examination of individual level data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG).6 A key to our empirical strategy is to determine whether any effect

of inequality is concentrated among those most likely to be adversely affected by it, namely those at the bottom of the income distribution. Individual level data also al-lows us to control for individual- level demographics and other state characteristics. We focus on lower- tail income inequality, defi ned as the ratio of household income at the 50th percentile to the 10th percentile of the distribution. We choose this measure of

inequality to be our baseline measure because the economic and cultural disparities resulting from this gap are more relevant to the lives of the poor, than say, the gap between those at the 90th percentile and the median.

We fi nd that women who grow up in low socioeconomic circumstances have more teen, nonmarital births when they live in higher inequality locations, all else equal. The proximate mechanism driving this is less frequent use of abortion, meaning that low- SES girls in more unequal places are more likely to “keep the baby” when they become pregnant. Our analysis controls for individual demographic characteristics and a broad array of state- level public policies (including welfare and abortion policies).

markets affect the propensity to marry among females. The estimates suggest that for white women and for highly educated black women, rising within- group male wage inequality had a sizable negative impact on the female propensity to marry between 1970 and 1990. Gould and Passerman (2003) conduct a similar study examining how intercity variation in male inequality affects the marital decisions of white women. They also fi nd a strong positive relationship between male wage inequality and the probability of a woman being single and interpret their fi ndings in the context of a search model. Note that unlike the Watson and McLanahan (2011) paper on marriage, these papers are not focused on low- income populations.

5. Watson (2009) presents evidence that as income inequality has increased over time, cities have become increasingly segregated along income lines.

We also consider a large set of potentially confounding state- level factors, and

con-fi rm that our fi ndings are not driven by these alternative explanations. For example, we directly test the role of income inequality against absolute income levels, poverty concentration rates, minority concentration rates, as well as other potentially important environmental factors such as social capital measures, religious composition, or politi-cal climate. Though we could never completely rule out the existence of an omitted factor, the robustness of the relationship is striking.7

Our scholarly contribution is twofold. First, we present empirical evidence sup-porting the role of income inequality in driving rates of early nonmarital childbear-ing among those at the bottom of the income distribution. Our estimates suggest that inequality can explain a sizable share of the variation in teen childbearing rates across states. To date, no other explanation can come close to explaining as much of the geo-graphic variation.8 Second, we believe our proposed economic model of young adult

decision- making in the face of short- versus long- term payoffs constitutes an impor-tant contribution to the literature in economics that considers adolescent behaviors such as juvenile crime, teen childbearing, and high school noncompletion. In our con-ceptualization, such so- called “risky behaviors” might be more appropriately consid-ered “drop out” behaviors, and our model suggests that adolescents will be more likely to choose to drop out of the mainstream climb to socioeconomic success when they view their chances of success as suffi ciently low. Though this paper is focused entirely on early nonmarital childbearing, we believe our model is applicable to a number of other contexts that involve current benefi ts and future economic costs.

II. Review of Previous Research on Early Nonmarital

Childbearing

The standard economics model of childbearing considers an individ-ual who maximizes utility over children and other consumption subject to a budget constraint (cf. Becker and Lewis 1973). Preferences are assumed to be given, and explanations have focused on differences in constraints, often generated by particular policies and institutions. The political scientist Charles Murray (1986) wrote in his book, Losing Ground, that the welfare system provided incentives for couples to have a child outside of marriage by reducing both the fi nancial rewards of marriage and the

fi nancial costs of out- of- wedlock childbearing. This hypothesis became politically popular among conservatives and helped usher in an era of welfare reform. It also

7. This stands in contrast to the observed correlation between aggregate income inequality and mortality, which has been shown to be fragile. For example, Deaton and Lubotsky (2003) fi nd that controlling for the proportion black negates the positive relationship between state and MSA level income inequality and mortal-ity. Those authors refer to earlier work by Mellor and Milyo (2001) that uses Census data to show that the correlation is likely spurious. They also describe a set of papers that fail to fi nd a robust relationship between income inequality and mortality using individual level data, including Fiscella and Franks (1997) and Daly, Duncan, Kaplan, and Lynch (1998).

spawned a vast empirical literature in economics investigating the issue. Moffi tt (1998 and 2003) provides an overview of the large literature on the topic, concluding that more generous welfare benefi ts likely have only a modest positive effect on rates of nonmarital childbearing. With regard to the variation across countries, the lower rate of teen childbearing in Europe with its much more generous welfare system provides a

prima facie case against the hypothesis that social support is largely to blame for high

rates of teen childbearing in the United States.

Economists have also examined a host of other policy and institutional factors rel-evant to the costs of avoiding or not avoiding a nonmarital or teen birth. A highly incomplete list of such studies includes previous work that we have conducted else-where on the effect of various policies and environmental conditions, such as restric-tive abortion policies (Levine, Trainor, and Zimmerman 1996; Levine 2003); wel-fare reform (Kearney 2004); labor market conditions (Levine 2001) and access to affordable contraception (Kearney and Levine 2009a). These empirical studies have generally found that changes in such “prices” do have impacts on teen and nonmarital childbearing, but individually these factors can account for only very small shares of the total variation in nonmarital childbearing.9

Other social scientists have suggested that teen childbearing is attributable to teens’ stage of cognitive development, arguing that they are not quite ready to make the types of decisions that would prevent a pregnancy (for example, Brooks- Gunn and Furst-enberg 1989; Hardy and Zabin 1991; Brooks- Gunn and Paikoff 1997). Behavioral economists O’Donohue and Rabin (1999) suggest that teens are “hyperbolic discount-ers,” who place disproportionate weight on present happiness as compared to future well- being. While limited decision- making capacity surely is an issue for some set of teens, these claims have an element of universality to them that cannot begin to explain the striking differences in rates of early nonmarital childbearing across socio-economic groups, over time, or across states or countries.

Another line of research considers the relationship between background disadvan-tage and rates of early childbearing (cf. Duncan and Hoffman 1990; An, Haveman, and Wolfe 1993; Lundberg and Plotnick 1995; and Duncan et al. 1998). It is well known that growing up in disadvantaged circumstances, such as in poverty or to a single mother, is associated with much higher rates of early childbearing. In a pre-vious examination of cohort rates of early childbearing, we fi nd that the proportion of a female cohort born economically disadvantaged—as captured by being born to a teen mother, a single mother, or to a mother with a low level of education—is tightly linked to the subsequent rate of early childbearing in that cohort (Kearney and Levine 2009b). But, strikingly, we fi nd that state and year of birth fi xed effects capture much of the variation. We interpret that fi nding as suggestive of the importance of some “cultural” dimension, otherwise unmodeled in that framework. In some sense this could be considered the launching point for this current research.

Although economists have been contributing to discussions of early nonmarital

9. Akerlof, Yellen, and Katz (1996) propose a “technology shock” hypothesis for the rise in nonmarital childbearing in the United States in the later 20th century. They relate the erosion of the custom of “shotgun

childbearing for several decades, the fi rst contributors to the discussion were other so-cial scientists. Their work pursued a parallel, rarely (if ever) intersecting track. Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s 1965 report fi rst drew attention to the issue of nonmarital child-bearing among black families in the United States, when the rate was one in three.10 At

about the same time, the social theories of the psychologist Clark (1965) and the an-thropologist Lewis (1969)—who developed the theory of the “Culture of Poverty”— were met with controversy. Lewis (1969) wrote the following: “The culture of poverty is both an adaptation and a reaction of the poor to their marginal position in a stratifi ed, highly individuated, capitalistic society. It represents an effort to cope with the feelings of hopelessness and despair that develop from the realization of the im-probability of achieving success in terms of the values and goals of the larger soci-ety . . . Women often turn down offers of marriage because they feel that it ties them down to men who are immature, punishing, and generally unreliable” (pp. 189–90).

This lack of opportunity was observed explicitly by Clark (1965), who wrote:

In the ghetto, the meaning of the illegitimate child is not ultimate disgrace. There is not the demand for abortion or for surrender of the child that one fi nds in more privileged communities. In the middle class, the disgrace of illegitimacy is tied to personal and family aspirations. In lower- class families, on the other hand, the girl loses only some of her already limited options by having an illegitimate child; she is not going to make a “better marriage” or improve her economic and social status either way. On the contrary, a child is a symbol of the fact that she is a woman, and she may gain from having something of her own. Nor is the boy who fathers an illegitimate child going to lose, for where is he going? The path to any higher status seems closed to him in any case. (p. 72)

The sociologist Wilson (1987) revived serious scholarship on the topic with his book The Truly Disadvantaged. The distinction between Wilson and Clark is largely the focus on the lack of jobs itself in Wilson, not the social attitude that results from the lack of jobs. Either way, the lack of opportunity is what is driving the childbearing outcomes in both viewpoints, as described in the following excerpt:

Thus, in a neighborhood with a paucity of regularly employed families and with the overwhelming majority of families having spells of long- term joblessness, people experience a social isolation that excludes them from the job network system that permeates other neighborhoods and that is so important in learning about or being recommended for jobs that become available in various parts of the city . . . Moreover, unlike the situation in earlier years, girls who become pregnant out of wedlock invariably give birth out of wedlock because of a shrink-ing pool of marriageable, that is, employed black men. (p. 57)

The relevant environmental factor for women in this argument is the weak marriage market that is attributable to the lack of jobs for men in the inner city. Wilson is clear to point out that his focus is on “social isolation” and not the “culture of poverty.”

More recently, Edin and Kefalas (2005) contributed an infl uential ethnographic account of nonmarital childbearing among poor women. They make the following observation: “. . . the extreme loneliness, the struggles with parents and peers, the wild behavior, the depression and despair, the school failure, the drugs, and the general sense that life has spun completely out of control. Into this void comes a pregnancy and then a baby, bringing the purpose, the validation, the companionship, and the or-der that young women feel have been so sorely lacking. In some profound sense, these young women believe a baby has the power to solve everything” (p. 10).

Our reading of these seminal and infl uential works is that they fi nd common ground in the notion that growing up in an environment where there is little chance of social and economic advancement leads young women to bear children outside of marriage. These women perceive that they have so little chance for success in life that they see no reason to postpone having a child and may even benefi t from having one, regardless of marital status.11

III. Empirical Framework

The social science literature reviewed above emphasizes the role of economic hopelessness and marginalization in driving the childbearing and marriage decisions of economically disadvantaged young women. We consider this to be po-tentially important in explaining why some places have so much higher rates of early nonmarital childbearing than others. Disadvantaged individuals who live in locations with more discouraging economic conditions will be more likely to have early non-marital births.

We focus our attention on one potential persistent economic condition: lower- tail income inequality. Income inequality tends to be persistent within a place. Using data from the IPUMS Censuses (described below) we fi nd that the correlation in the 50 / 10 ratio between the 1980 and 2000 Census years averages 0.74 across states.12 This

indicates that states that tend to have relatively high levels of inequality remain the high- inequality states, and likewise for low inequality states. In addition, income in-equality shows a strong correlation with rates of early nonmarital childbearing.13

11. Many of these early works focus directly on the issue of race. Now that rates of early nonmarital child-bearing are high for all women (albeit still higher for black women), this is less an issue of race today. 12. While overall inequality (as measured by the 90 / 10 ratio of income, for example) has increased dramati-cally in recent decades, this increase is driven by upper- tail income inequality, as in the gap between the 90th and the 50th. (See Autor, Katz, and Kearney 2008.) Lower- tail income inequality has generally plateaued or

An important step in establishing causation is to determine that inequality oper-ates on those who are most likely to be negatively impacted by it. With this in mind, our main empirical test is based on determining whether low SES women in places with a larger lower- tail income gap are more likely to have an early nonmarital birth compared to higher SES women in those locations. We estimate regression models for a series of fertility outcomes (birth, conception, etc.) controlling for year- of- birth

fi xed effects and state fi xed effects. We also control for individual level demographics, public policy variables, and time- varying labor market conditions in these models.

The key variable in our models is the interaction between long- term measures of inequality and a woman’s socioeconomic status. We are interested in explaining per-sistent differences in rates of early nonmarital childbearing across places. We therefore focus our analysis on “fi xed” characteristics of environments. In terms of inequality, this means we empirically consider variation in long- term averages in state and na-tional measures of inequality.

More formally, we estimate regression models for outcomes by age 20 of the form:

(1) Outcomeisc=β0+β1(Is⋅LSisc)+β2(Is⋅MSisc)+β3LSisc+β4MSisc

+β5Xisc+β5Esc+γs+γc+εisc

where I is our measure of inequality, LS and MS are indicators of low and middle SES, respectively, and the interaction terms are the main regressors of interest. They represent the differential response of low and middle SES teens to inequality relative to high SES teens. The subscripts i and s index individuals and states, and c indexes birth cohorts. The terms γs and γc represent state and birth cohort fi xed effects, respec-tively. The vector X consists of additional personal demographic characteristics—age, age squared, race / ethnicity, and an indicator for living with a single parent at age 14.

The vector E captures environmental factors including relevant public policies and labor market conditions in the state- year: the unemployment rate, an indicator for a welfare family cap, the maximum welfare benefi t for a family of three, an indicator for SCHIP implementation, an indicator for whether the state Medicaid program covers abortion, an indicator for whether state abortion regulations include parental notifi ca-tion or mandatory delay periods, and whether the state Medicaid program includes expansion policies for family planning services. (See Kearney and Levine, 2009a for a discussion of these expansion policies.) By including all of these individual and state level controls in the model, our estimated effect of inequality for low- SES women is net of effects driven by policies that might be correlated with inequality.14

Our primary question of interest is whether β1 is positive: Are low- SES women in high inequality states relatively more likely to have a nonmarital birth by age 20? We consider the multiple channels through which a difference in birth rates could be real-ized. First, an individual can take actions with regard to sexual behavior and contra-ceptive practices; low SES women in more unequal places may be more likely to get pregnant. Second, a nonmarital childbirth could be avoided through the choice to end

relationships has been called into question in other contexts. See Deaton and Lubotsky (2003) on the relation-ship between inequality and mortality, for example.

a pregnancy; low SES women in more unequal places may be relatively less likely to choose an abortion to end her pregnancy. And fi nally, nonmarital births depend upon the parents choosing to remain unmarried after a pregnancy occurs; low SES women in more unequal places may be relatively less likely to get married before the birth through a so- called “shotgun” marriage.

One limitation of this modeling approach is that any other characteristic of the socioeconomic environment that might be correlated with inequality and also directly related to nonmarital early childbearing propensities among low- SES women will be captured by our long- run inequality / SES interaction term. Although it is impossible to completely rule out this form of omitted variable bias, we examine whether introduc-ing additional interactions of SES with other potentially troublesome characteristics change our results. More formally, we estimate “horse race” models that take the form:

(2) Outcomeisc=β0+β1(Is⋅LSisc)+β2(Is⋅MSisc)+β3(As⋅LSisc)+β4(As⋅MSisc)

+β5LSisc+β6MSisc+β7Xisc+β8Esc+γs+γc+εisc

This specifi cation is largely the same as that in Equation 1 except that we now include alternative factors (A) that are time invariant within states and we interact them with an indicator for low SES.

We consider two categories of alternatives. The fi rst includes other features of the income and wage distribution. The second includes other social measures that are more directly focused on identifying alternative explanations—political composition of the state, a measure of religiosity of the state, the percentage of the population that is minority, the incarceration rate, poverty rate, and Putnam’s Social Capital Index. We describe all of the alternatives we consider in more detail when we report the results of our analysis.

IV. Data Description

Our analysis of U.S. fertility outcomes relies on data from the 1982, 1988, 1995, 2002, and 2006–08 surveys of the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG).15 These surveys provide observations for over 42,000 women between the

ages of 15 and 44. In all of our subsequent analyses, we restrict our attention to women who have turned age 20 or 25 (depending on analysis) in 1976 or afterward. We im-pose the year restriction to avoid much of the social and behavioral changes that were associated with the introduction and diffusion of the birth control pill in the 1960s and abortion legalization in the early 1970s. We are left with 27,000 observations.

Each survey contains complete pregnancy histories, which we use to generate

sures of pregnancies and pregnancy resolution (including childbearing) by age 20 (that is, through age 19). To deal with potential misreporting of abortion, we defi ne as an outcome “pregnancy failure,” which includes either a miscarriage or an abortion. This measure should capture behavioral changes in abortion regardless of how they are reported as long as the pregnancy itself is reported. It seems reasonable to assume that the vast majority of movements in pregnancy failures are generated from changes in abortion decisions. Data on age at fi rst marriage is also available so that we can ascertain whether the observed pregnancies occurred before marriage or whether a so- called “shotgun marriage” took place between the time of pregnancy and birth.

The importance of using microdata for our analysis is that we are able to link fertil-ity histories to personal characteristics. In particular, the hypothesis we test is about the impact of inequality on the fertility decisions of low SES teens, so it is critical to be able to identify women who satisfy an operational defi nition of low socioeconomic status. Because the data do not include information about family income during child-hood, we categorize women according to their mother’s level of education.

The NSFG data reveal important trends over time. The rate of early childbearing (by age 20) has fl uctuated around 20 percent since the mid- 1970s, with a slight downward trend to 17 percent among the most recent cohort. This stability masks dramatic dif-ferences in marital versus nonmarital early childbearing. The percentage of women who had a marital birth by age 20 fell from 14 to 3 percent from the mid- 1970s to 2006, while the percent with a nonmarital birth rose from 8 to 14 percent. The data also reveal a dramatic upward trend in the rate at which unmarried pregnant women (below age 20) carry their pregnancy to term. In the mid- 1970s, about 40 percent of the time this occurred, as compared to nearly two- thirds of the time at the end of the period. This increase can be attributed partly to a reduction in the fraction of nonmari-tal conceptions that result in a marinonmari-tal birth (“shotgun marriages”). Since around 1980, the trend has also been driven by a reduction in pregnancy failures, likely the result of less frequent use of abortion. In the most recent year of data, a young woman who gets pregnant outside of marriage has a 62 percent probability of having a nonmarital birth, a 10 percent probability of getting married before the birth, and a 28 percent probability of aborting or having a miscarriage.

Crucially, we are able to obtain state identifi ers for the NSFG, which allows us to link individual respondents to state- level characteristics.16 We attach to the NSFG data

on individual women a set of environmental factors that existed in the respondent’s state of residence and the year in which she turned age 19; when we analyze birth out-comes by age 25, we attach state- level factors for the year in which a woman turned age 24. These factors include the policy variables listed above and the unemployment rate in that year. We additionally attach alternative state characteristics measures that we use in our horse race specifi cations, including measures of political and religious climate.

Of primary interest, we attach measures of income inequality in the respondent’s state of residence.17 We created these measures using microdata from the 1980, 1990,

and 2000 Censuses along with the 2006–08 American Community Surveys on house-hold income. These data are available from IPUMS- USA (Ruggles 2010). Using these data, we estimated income cutoffs at the 10th and 50th percentiles for each state and

survey year and then generate ratios of these measures (like the 50 / 10 ratio) as our baseline measure of inequality. We then compute the average within states to generate our measure of long- term lower- tail inequality.18

V. Results

A. Analysis of NSFG Data

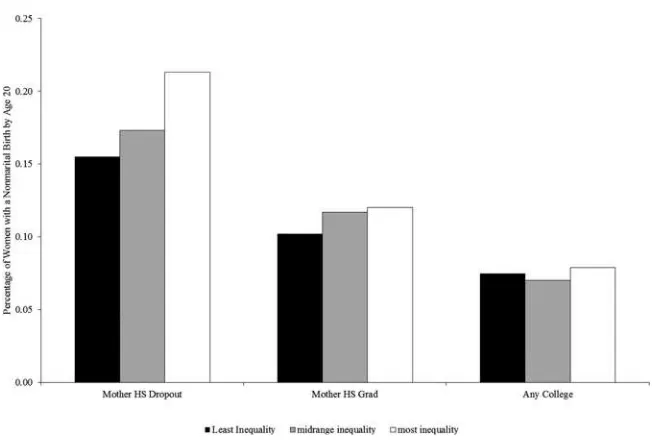

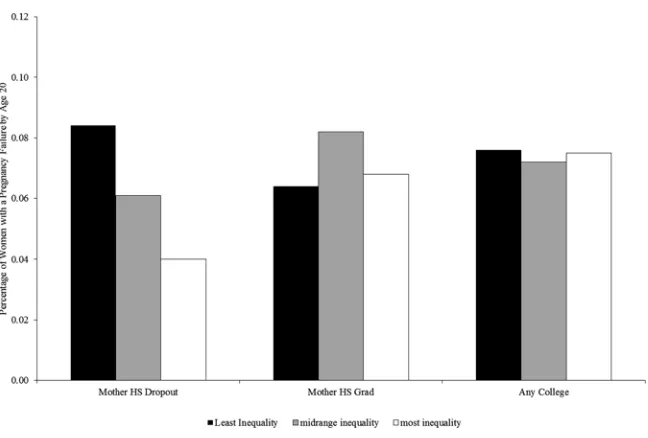

Before presenting our formal econometric results, we conduct a descriptive analysis of the NSFG data that is comparable in spirit to our regression models. We compare fertility outcomes across three categories of states—high, medium, and low inequality states—for women in three SES categories: women whose mothers were high school dropouts, high school graduates, and those who had any college education. This com-parison is essentially a stylized version of the interaction of SES and state inequality measures, previewing the regressions to follow. Figure 5 presents these unadjusted

17. We have considered whether the state is the right level of aggregation for this analysis. First, there are conceptual issues. A potentially important consequence of high levels of income inequality is greater resi-dential and institutional segregation. To focus on a smaller geographic unit would thus lose this dimension of inequality. This leads us to prefer the state to something smaller. However, in very populous diverse states, such as Texas or California, the state might be too disparate a measure, and the appropriate geographical unit might be something smaller. Mayer’s (2001) study of education outcomes and state- level income inequality also grapples with the issue of what is the appropriate unit of aggregation in a study of the consequences of income inequality, and her paper includes a thoughtful discussion of this issue. Second, in terms of data and empirical methodology, there are challenges to using a geographic unit smaller than the state. One empirical concern is mobility. The geographic identifi er in the NSFG is the location of current residence and mobility is a much greater concern at the local level than at a broader level. A second data concern is limited sample size. The only substate identifi er available even in restricted NSFG data is the county of residence. This limits the sample size available for our analysis because public use census data only identifi es county of residence for 40 percent of the population. Nevertheless, we have conducted a county- level analysis identical in form to that reported here using the subset of NSFG respondents who live in counties for which Census income data are available. The pattern of results are similar than those reported here, but smaller in size. Rather than a coeffi cient of 0.053 (0.015) in Column 1 of Table 1, the comparable coeffi cient with county data is 0.031 (0.012). This is consistent with the attenuation bias that would result from cross- county migration. It is also consistent with the idea that some of the effects of inequality are not captured when one looks at a smaller level of geography.

differences. They reveal that high SES women (defi ned as having a college- educated mother) exhibit little variation in early nonmarital childbearing across states that dif-fer in their level of income inequality. Low SES women (defi ned as having a mother who dropped out of high school) are more likely to give birth to a child at a young age outside of marriage if they live in a state with a larger lower- tail income gap. Moving from a low inequality state to a high- inequality state (which represents roughly a one point increase in the 50 / 10 ratio) appears to increase the rate of nonmarital childbear-ing by age 20 by around fi ve percentage points.

We conduct a similar exercise for conception, pregnancy failure, and shotgun mar-riage. These comparisons show no evidence of differential patterns by SES by inequal-ity ranking for conception or shotgun marriage by age 20. In contrast, we show in Figure 6 that rates of pregnancy failure are a little over four percentage points lower among low SES women in high inequality states, as compared to low SES women in low inequality states. This means that the differences in early nonmarital childbearing can be attributed almost entirely to differences in the rate of pregnancy failure (likely due to differences in the use of abortion). We proceed to a more rigorous examination of these comparisons using the econometric model described above.

Table 1 reports the main regression estimates. The fi rst column in the upper panel of this table explores nonmarital births by age 20 as the outcome. The interaction between the 50 / 10 ratio and having a high school dropout mother represents β1 in our econometric model. It indicates that low SES girls in a state with a higher lower- tail income gap are more likely to have a nonmarital birth by age 20, all else equal. As

Figure 5

we saw earlier, a one point change in the 50 / 10 ratio roughly captures the movement from a low inequality state to a high inequality state. In this case, that movement is predicted to increase early nonmarital childbearing by 5.3 percentage points for those women whose mothers were high school dropouts. This point estimate is very similar to the unadjusted difference that we observed in Figure 5, suggesting that the other covariates in the model have very little correlation with the interaction term of interest and / or early nonmarital childbearing.

The remainder of the top panel of the table focuses on other nonmarital outcomes and all marital outcomes by age 20. In Column 3, we see that much of the reason why nonmarital childbearing among low SES women rises with inequality is that abortion rates, as captured by pregnancy failures, fall. The magnitude of this estimate indicates that moving from a low- inequality state to a high- inequality state reduces the likelihood of a pregnancy failure by 4.2 percentage points. We cannot statistically distinguish this estimate from the 5.3 percentage point increase in early nonmarital childbearing. This suggests that the rise in early nonmarital births associated with greater inequality is mainly attributable to fewer abortions.

Column 2 provides no evidence that the likelihood of conception is affected. We

fi nd little support for an impact of inequality on marital fertility. In Column 7, we focus on shotgun marriage. We fi nd a statistically signifi cant reduction in the likeli-hood of shotgun marriage among low- SES women as lower- tail income inequality increases.

Interestingly, when we focus on moderate SES women as captured by daughters of

Figure 6

T

he

J

ourna

l of H

um

an Re

sourc

es

Table 1

Impact of Long- Term Inequality on Marital and Nonmarital Fertility Outcomes by Ages 20 and 25, by Socioeconomic Status

Nonmarital Outcomes Marital Outcomes

Shotgun Marriage

Birth 1

Conception 2

Pregnancy Failure

3

Birth 4

Conception 5

Pregnancy Failure

6 7

By Age 20

50 / 10 ratio* 0.053 –0.006 –0.042 –0.026 –0.006 0.003 –0.018

Mom high school dropout (0.015) (0.018) (0.015) (0.017) (0.016) (0.004) (0.009)

50 / 10 ratio* 0.021 –0.013 –0.013 –0.027 –0.004 0.002 –0.013

Mom high school graduate (0.012) (0.018) (0.015) (0.010) (0.006) (0.003) (0.007)

By Age 25

50 / 10 ratio* 0.040 –0.039 –0.022 –0.041 0.008 –0.010 –0.050

Mom high school dropout (0.013) (0.026) (0.025) (0.025) (0.029) (0.006) (0.014)

50 / 10 ratio* 0.003 –0.049 –0.020 –0.026 0.002 –0.003 –0.021

Mom high school graduate (0.014) (0.018) (0.017) (0.012) (0.016) (0.004) (0.010)

high school graduates, we fi nd that the point estimate for the increase in nonmarital births is attenuated, and now there is a statistically signifi cant reduction in marital births, of nearly the same (opposite- signed) magnitude.19 Presumably these women

are at some, albeit reduced, risk of poor economic outcomes that may be exaggerated in high inequality states. For them, greater inequality is associated with fewer marital births. This suggests that a reduced prevalence of shotgun marriage is the pathway, as confi rmed in Column 7. These results are similar to the results for women in their young 20s, described below.

The lower panel of Table 1 replicates this analysis, focusing on childbearing / mari-tal outcomes by age 25 rather than age 20. Including somewhat older young adults increases the relevance of shotgun marriages in these fi ndings. We continue to fi nd that nonmarital childbearing increases for low SES women when they live in high- inequality states, but we fi nd a similar drop in marital childbearing (although the latter is not quite signifi cant). Changes in the likelihood of a shotgun marriage explain the divergent pattern.20

B. An Investigation of Alternative Mechanisms

Our approach to statistical identifi cation focuses on the interaction between socioeco-nomic status and a measure of (fi xed) long- term average income inequality. A causal interpretation of the role of income inequality may not be warranted if there is some other important state fi xed factor that is omitted, but strongly correlated with inequal-ity and directly related to childbearing outcomes for low SES women. To address this possibility, we examine the impact of including a host of alternative state characteris-tics interacted with SES measure.21

We consider two sets of alternative factors. The fi rst consists of other features of state income and wage distributions that may matter, but are different than our mea-sure of inequality at the bottom of the income distribution. We consider fi ve alterna-tives. First, we include the 90 / 50 ratio from the income distribution, calculated in the same way we described earlier regarding the 50 / 10 ratio. Since that measure identifi es inequality at the top of the distribution rather than the bottom, we would not expect it to have a very strong impact on early childbearing among low SES women. Second

19. Though our measure of income inequality is not wage inequality, this fi nding could be consistent with the marriage search model story of Loughran (2002) and Gould and Passerman (2003), in which greater male wage inequality induces women to search longer for a marriage partner.

20. We have estimated these models separately for blacks and Hispanics, but sample sizes drop substantially and statistical power falls as a result. For the outcomes by age 20, among the sample of Hispanic women (n = 4,086), the estimated coeffi cient (standard error) on the interaction term of interest is 0.060 (0.047) for nonmarital births, 0.020 (0.050) for nonmarital pregnancy failure, and –0.065 (0.024) for shotgun married. These results suggest that low- SES Hispanic teens living in more unequal places are less likely to get married conditional on getting pregnant. For the outcomes by age 20, among the sample of black women (n = 6,117), the estimated coeffi cient (standard error) on the interaction term of interest is 0.025 (0.033) for nonmarital births, –0.085 (0.025) for nonmarital pregnancy failure, and 0.018 (0.014) for shotgun married. These results suggest that low- SES black teens living in more unequal places are less likely to terminate a pregnancy, conditional on getting pregnant. The pattern of results is qualitatively similar for these racial / ethnic groups for outcomes by age 25.

and third, we consider the absolute level of income at the bottom and middle of the income distribution, as opposed to the relative distance between these measures. Per-haps it is not inequality that matters for a young woman’s decision, but rather how low the 10th percentile of the income distribution is or where the 50th percentile is. Fourth

and fi fth, we consider the average wage ratio for high school graduates relative to high school dropouts and for college graduates relative to high school graduates. These outcomes provide a measure of the returns to education in the state and provide a way to examine whether a higher return to moving up the ladder can actually reduce the likelihood of early nonmarital childbearing among low SES women.22

In Table 2, we report the results of estimating Equation 2 including these fi ve alter-native measures. Column 1 reports the main coeffi cients of interest from Equation 1— namely, a point estimate of 0.053 (0.015) on the interaction of the 50 / 10 ratio and our maternal education measure of low- SES status. As we show in the remainder of the table, the coeffi cients on each of these alternative measures is not statistically signifi -cant (at the 5 percent level) and including these additional variables, does not attenuate the coeffi cient on our main variable of interest.

We next consider a set of six alternative state characteristics that capture alternative explanations that tend to fall outside the framework of our proposed model. We fi rst consider the political culture of a state, which we capture by including the average percentage of voters favoring Democratic candidates averaged within state between the 1972 and 2008 Presidential elections.23 Second, we recognize that religious beliefs

in a state may also be a contributing factor, so we include an index of religiosity as well.24 Third, we explore the role played by differences in states’ percentage of the

population that is minority (defi ned as individuals who are not white, non- Hispanic). Fourth, we include the incarceration rate in the state.25 We also consider the state

characteristic “social capital.” Putnam (2000) argues that the loss of social capital has contributed to the high teen birth rate, so we include his measure of social capital as a potential alternative.

The fi nal alternative we consider is the poverty rate in the state.26 One could provide

alternative perspectives regarding why or how the aggregate poverty rate would mat-ter. For instance, Wilson (1987) argues that poor adults fail to provide successful role models for neighborhood children that would discourage early or unmarried child-bearing. Jencks and Mayer (1990) propose that in poor neighborhoods the relative absence of quality educational and employment opportunities for youth may lead to comparatively fewer social and economic costs to unmarried childbearing. The em-pirical evidence on this point is mixed, with some studies fi nding an effect of

neigh-22. We calculated these wage ratios using data the 1980, 1990, and 2000 Censuses along with the 2006– 08 ACS, estimating hourly wages for full- time workers (greater than 1,500 hours in the year) by level of education.

23. The source of these data is David Leip’s Atlas of Presidential Elections, http: // uselectionatlas .org /. 24. The source of these data is Gallup Poll, State of the States: Importance of Religion. January 28, 2009. www .gallup .com / poll / 114022 / state- states- importance- religion .aspx

25. The incarceration data are compiled by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Offi ce of Justice programs, www .ojp .usdoj .gov.

borhood poverty on individual teen childbearing rates, and a number of others failing to fi nd an effect.27

The results of this analysis are reported in Table 3. Again, the fi rst column replicates the fi rst column of Table 1 for the purposes of comparison. The results provide no evidence that any of these additional measures has an effect on early nonmarital child-bearing rates among low- SES women. Nor does the inclusion of these variables alter our conclusion about the role of inequality.28 The bulk of the evidence in Tables 2 and 3

is strongly suggestive that inequality has an impact on early nonmarital childbearing in the United States that is not simply picking up the effect of some other state level factor.

C. Evaluating the Magnitude of the Effects

Our estimates suggest that income inequality can account for a sizeable share of the variation across states in rates of teen childbearing. In our data from the United States, we observe that 13.6 percent of women experienced a teen, nonmarital childbirth in high inequality states compared to 10.1 percent of women in low- inequality states (over the sample period). In those high- inequality states, roughly 34 percent of teens were daughters of high school dropout mothers (per our tabulations of the NSFG data). Based on our estimates in Table 1, low SES women in high- inequality states were 5.3 percentage points more likely to have a nonmarital, teen birth compared to low SES women in low- inequality states. If the level of inequality in the high- inequality states decreased to the level of the low- inequality states, we would expect teen, nonmarital childbearing to decline by 0.053*0.34*1 = 0.018 or 1.8 percentage points. This represents 1.8 / (13.7 – 10.2) = 0.51 or 51 percent of the gap in the likeli-hood of nonmarital childbearing by teens between high- and low- inequality states.

VI. An Economic Model of Young Adult Decision

Making

In this section we offer a framework within which to interpret the em-pirical results. Inequality is positively related to early nonmarital childbearing among

27. South and Crowder (2010) provide a review of this literature in their recent paper on the issue. They build upon the existing literature by considering childhood exposure to poverty as measured by more than simply a point in time, as well as considering the effect of poverty in one’s own neighborhood along with the poverty rates of surrounding areas. This recognition that neighborhoods are embedded in a larger system of communities makes their study particular relevant to the question we are examining in this paper. Using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), they fi nd that the effect of local neighborhood poverty is especially pronounced when surrounding neighborhoods are economically advantaged. This fi nding is potentially consistent with our fi nding of an important role for aggregate state- level inequality. In the speci-fi cation we estimate here, we consider state level inequality and state level poverty, not neighborhood level poverty. In fact, in light of South and Crowder (2010), it might very well be the case that the combination of living in a high poverty neighborhood and an unequal state is particularly distressing to the social outcomes of poor youth.

T

he

J

ourna

l of H

um

an Re

sourc

es

Table 2

Impact of Alternative State Economic Conditions on Nonmarital Fertility by Ages 20 and 25, by Socioeconomic Status

50 / 10 Ratio

1

90 / 50 Ratio

2

10th

Percentile of Income

3

50th

Percentile of Income

4

HS Grad to high school High School Dropout Wage

Premium 5

College Grad to HS Grad Wage Premium

6

Correlation between 50 / 10 ratio and characteristic:

— 0.709 –0.615 –0.168 0.127 0.347

By Age 20

50 / 10 ratio* 0.053 0.069 0.062 0.056 0.052 0.054

Mom high school dropout (0.015) (0.021) (0.019) (0.015) (0.015) (0.014)

50 / 10 Ratio* 0.021 0.000 0.022 0.022 0.017 0.012

Mom high school graduate (0.012) (0.016) (0.017) (0.012) (0.011) (0.011)

State characteristic* — –0.065 0.028 0.028 0.049 –0.036

Mom high school dropout — (0.066) (0.049) (0.049) (0.093) (0.072)

State characteristic* — 0.076 0.003 0.005 0.128 0.096

K

ea

rne

y a

nd L

evi

ne

21

50 / 10 ratio* 0.040 0.057 0.034 0.039 0.042 0.045

Mom high school dropout (0.013) (0.018) (0.019) (0.014) (0.013) (0.013)

50 / 10 ratio* 0.003 –0.006 0.003 0.003 0.003 –0.006

Mom high school graduate (0.014) (0.018) (0.019) (0.014) (0.014) (0.013)

State characteristic* — –0.064 –0.020 –0.021 –0.106 –0.089

Mom high school dropout — (0.055) (0.049) (0.048) (0.074) (0.083)

State characteristic* — 0.030 0.001 0.001 –0.003 0.092

Mom high school graduate — (0.047) (0.047) (0.046) (0.059) (0.064)

T

he

J

ourna

l of H

um

an Re

sourc

es

Table 3

Impact of Alternative State Characteristics on Nonmarital Fertility by Ages 20 and 25, by Socioeconomic Status

50 / 10 Ratio 1

Percentage of Votes to Democrats

2

Index of Religiosity

3

Percentage of Population that

Is Minority 4

Incarceration Rate

5

Poverty Rate

6

Social Capital

Index 7

Correlation between 50 / 10 ratio and characteristic:

— 0.358 0.249 0.368 0.414 0.499 –0.598

By Age 20

50 / 10 ratio* 0.053 0.047 0.057 0.053 0.058 0.060 0.049

Mom high school dropout (0.015) (0.019) (0.016) (0.016) (0.018) (0.024) (0.016)

50 / 10 ratio* 0.021 0.019 0.019 0.010 0.012 0.021 0.015

Mom high school graduate (0.012) (0.015) (0.010) (0.011) (0.012) (0.021) (0.016)

State characteristic* — 0.131 –0.047 0.000 –0.004 –0.001 –0.003

Mom high school dropout — (0.121) (0.079) (0.001) (0.006) (0.002) (0.012)

State characteristic* — 0.038 0.043 0.001 0.009 0.002 –0.007

K

ea

rne

y a

nd L

evi

ne

23

50 / 10 ratio* 0.040 0.027 0.047 0.048 0.046 0.030 0.049

Mom high school dropout (0.013) (0.015) (0.011) (0.013) (0.012) (0.021) (0.011)

50 / 10 ratio* 0.003 –0.008 0.002 –0.004 –0.004 0.001 –0.016

Mom high school graduate (0.014) (0.014) (0.015) (0.014) (0.017) (0.021) (0.020)

State characteristic* — 0.230 –0.089 –0.001 –0.009 0.001 0.019

Mom high school dropout — (0.123) (0.074) (0.001) (0.007) (0.003) (0.015)

State characteristic* — 0.163 0.008 0.000 0.003 0.000 –0.013

Mom high school graduate — (0.097) (0.062) (0.001) (0.006) (0.002) (0.013)

low- SES women in a way that could reasonably be interpreted as causal. The empiri-cal results above show that this relationship is driven by a greater tendency to “keep the baby” among low- SES girls in more unequal places. This is consistent with the observation by Clark (1965) that, “In the ghetto . . . There is not the demand for abor-tion or for surrender of the child that one fi nds in more privileged communities.” We propose a model of young adult decision- making that illustrates how income inequal-ity could have this effect on the decisions made by young adults. This model captures the essential ideas expressed in the sociology and anthropology literature on the topic in a parsimonious model of rational decision- making.

In this model, a young, unmarried woman’s decision to have a baby is based on a comparison of her expected lifetime utility if she has a baby in the current period compared to expected lifetime utility if she delays childbearing. An individual chooses to have a baby in the current period if the following condition is met:

(3) uob

delays childbearing. V is the present discounted sum of future period utility.

We propose that for young, unmarried women of low socioeconomic status (SES) having a baby is utility- enhancing in the current period, such that ub > ud. This

propo-sition refl ects the description from Edin and Kefalas (2005) above, whereby a baby is seen as bringing “purpose, the validation, the companionship, and the order” otherwise missing from many of these women’s lives. If ub < ud, it is never optimal to have a

baby in the current period and the model trivially predicts “delay” to the optimizing choice. It seems reasonable to expect that for the majority of high- SES young women,

ub < ud, and the results of the empirical analysis are consistent with that supposition.

For unmarried young women, having a baby in the current period negatively affects expected future utility by leading to lower levels of consumption in the future. For simplicity, we characterize utility in future periods as taking high and low values,

Uhigh and Ulow, respectively. We assume that childbearing at an early age reduces the

likelihood of achieving Uhigh. There are two likely mechanisms, the

fi rst through the labor market and the second through the marriage market. With regard to the fi rst, we posit that having a baby makes it more diffi cult for women to acquire human capi-tal, decreasing the future stream of own earnings, and thereby lowering subsequent income and consumption. Having a baby while young and unmarried is also likely to be a hindrance in the marriage market, and would thereby reduce the likelihood of improving one’s economic condition through a successful marriage. We defi ne Ulow to

be the level achieved by a young woman who does not delay childbearing. The pres-ent discounted value of the young mother’s future utility stream is thus deterministic and captured by Vlow. If the young woman delays childbearing, there is some positive

probability p that she will achieve the “high” utility position in future periods. As we have defi ned things, a young woman who has a baby in the current period is neces-sarily assigned to a low position in the income distribution. Our model assumes that if she delays childbearing, she has some probability of achieving the high income / consumption level.29

We can therefore write the condition to have a baby in the current period as follows:

This condition indicates that the change in lifetime utility from delayed childbearing comes from two opposite- signed sources: (1) the loss of current period enjoyment of a baby and (2) a positive probability of achieving the high- utility state in the future. We have implicitly assumed that the delay in childbearing causes no change in the fu-ture lifetime enjoyment of the child itself (say, by making childlessness a more likely outcome). In other words, the decision we are modeling is to have a baby today versus having a baby in the subsequent period. So the direct utility loss from not having a child today is limited to the loss in current period utility.

Rearranging terms, we see that a young woman will choose to delay childbearing in the current period if and only if:

(5) pVhigh

Of course, the young woman does not perfectly observe p. Instead, she bases her deci-sion on her perception of p. Let us call this subjective probability q, and rewrite the condition for delaying childbearing:

(6) qVhigh+(1−q)Vlow>Vlow+(uob−uod)

If a young woman perceives that she has a sizable chance at achieving economic success—and thereby capturing Vhigh—by delaying childbearing, the comparison

is more likely to favor the choice “delay.” On the other hand, if the young woman

perceives that even if she delays childbearing her chances of economic success are

suffi ciently unlikely—in other words, if q is very low—then the comparison is more likely to favor having a baby in the current period.30

Rearranging Expression 6, we can defi ne a reservation subjective probability qr

such that a young woman will choose to delay childbearing if and only if:

(7) q≥qr

We propose that one’s perception of the likelihood of economic success, q, depends on her position in the income distribution, as proxied for by SES status, such that

dq / d(SES) > 0. This supposition fi nds empirical support in tabulations of data from the 1979 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79). That survey includes questions about expectations of future success and perceived control over one’s life, as captured by the Rotter Scale Index. We tabulate these variables by maternal education, which we use as our proxy for SES status (as described below). Among young women whose mothers attended college, 32 percent report a high likelihood of achieving her occupational aspirations; this compares to only 18 percent of young women whose

corresponding to “low” and “high” positions in the overall income distribution leads the model to have an ambiguous prediction on the relationship between inequality and early, nonmarital childbearing, as we show below. It is thus a conservative modeling approach, given our main hypothesis.

mothers are high school dropouts were optimistic. Similarly, on the Rotter Scale of control over one’s life (which ranges from 0 for total control to 16 for no control), the average values for daughters of mothers who attended college was 8.01 compared to 9.24 for daughters of high school dropouts.

We additionally propose that one’s perceived probability of success is a function of the interaction of being low SES and inequality, such that dq / d(ineq) | (SES = low) < 0. The further down in the income distribution one fi nds herself and the more inequality that exists, the lower is the perception of economic success q. This hypothesis rests on the assumption that inequality and mobility are negatively correlated, a premise that is supported by cross- country comparisons in these outcomes.31

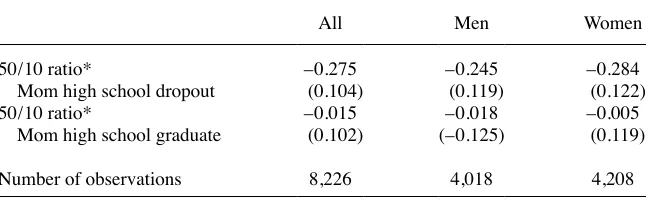

We provide additional empirical support for this proposition using data from the restricted- use NLSY79 Geocode data. We distinguish youth respondents by their parents’ educational attainment and examine whether those children whose mothers dropped out of high school have lower levels of “permanent income” later in life when they grow up in a high inequality state. For the purposes of this analysis, permanent income is defi ned to be the average of all infl ation- adjusted values of family income observed 15 or more years after the original 1979 survey, when youth respondents are in their late 20s or older. The sample used in this exercise includes all 8,226 re-spondents who lived with at least one of their parents at age 14 and who provided any income values in the 1994 survey or beyond. We assign the level of inequality to each respondent based on the respondents’ 1979 state of residence. Then we estimate regression models that are analogous to those we have already estimated using NSFG data focusing on early nonmarital nonmarital childbearing outcomes that we reported in Table 1.32

Table 4 reports the results of this analysis. The results show that children from low SES households (mother dropped out of high school) have lower permanent incomes as adults when they grow up in a high- inequality state. The impact is similar for both boys and girls. Children growing up in low SES households who live in a state with high lower- tail inequality are estimated to have permanent incomes that are over 30 percent lower than similar children in low lower- tail inequality states (where high- and low- inequality states are distinguished by a one point increase in the 50 / 10 ratio, as we used earlier). These fi ndings are somewhat imprecise, but they are statistically different from zero. If perceptions of economic opportunity are gauged on actual out-comes, then these fi ndings are consistent with our hypothesis.

As considered in the empirical section, the fi nal outcome of a nonmarital birth

31. We have plotted data on the intergenerational earnings elasticity (from Corak 2006)—which is inversely related to intergenerational mobility—against the Gini coeffi cient (from United Nations 2009) for a set of nine countries. The data shows a clear upward sloping pattern; a bivariate regression yields a slope parameter of 1.96 and an R squared of 0.642. Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland all have low inequality and low intergenerational earnings elasticity; the United Kingdom and United States have high levels of both; Germany and France fall along the line in the middle of the distribution; and Canada is a bit of an outlier with mid- level inequality but a low intergenerational earnings elasticity.

depends on both the outcome of giving birth and of remaining unmarried. Under an assumption of assortative mating, it is easy to see that conditions that lead a young woman to have a low subjective probability of her own economic success will also lead her to have a relatively low subjective probability associated with the likelihood that her male partner will achieve economic success. So, the greater the inequality, the lower would be the perceived likelihood that a male partner will bring economic advantages, and the model predicts a lower level of shotgun marriages. The results presented in Tables 1 and 2 for the shotgun marriage outcome by age 25 are consistent with this prediction.

There are two additional noteworthy features of the model. First, the prediction with regard to inequality is not unambiguously signed within the model. Expression 7 shows that qr varies inversely with the distance between Vhigh and Vlow, which in the

simplest case may be thought of as inequality. In fact, one could interpret this differ-ence as a greater return to effort.33 If so, then greater inequality would lower

reser-vation q, and could lead to less early childbearing. However, our empirical results suggest that the relationship between inequality and childbearing for low SES women is positive. The empirical results are consistent with the idea that on net, inequality generates desperation, not aspiration, among those at the bottom of the distribution.

Second, in this model future utility is appropriately discounted. The model does not require any present- biased decision- making, also known as quasihyberbolic discount-ing, to explain the choice that favors current period utility. If we add present- biased decision- making to the model, it would simply amplify the effect of a lower q and make the decision lean even more heavily in favor of having a baby in the current period.

33. We explored this proposition earlier, examining the impact of changes in the college / high school wage premium.

Table 4

Relationship Between Socioeconomic Status, Income Inequality, and “Permanent Income”

All Men Women

50 / 10 ratio* –0.275 –0.245 –0.284

Mom high school dropout (0.104) (0.119) (0.122)

50 / 10 ratio* –0.015 –0.018 –0.005

Mom high school graduate (0.102) (–0.125) (0.119)

Number of observations 8,226 4,018 4,208

To summarize this section, if inequality heightens feelings of economic despair or marginalization, our model provides a rationalization for the empirical fi ndings presented above. It also links our econometric analysis and fi ndings to a large body of social science research on early nonmarital childbearing that has largely gone unex-plored by economists.

VII. Final Discussion

This paper has presented a new set of fi ndings regarding the large, persistent cross- sectional variation in teen childbearing. We used individual- level data from a large, national dataset to investigate the extent to which income inequality— and other economic and social conditions—relates to rates of early nonmarital child-bearing. We fi nd that women who grow up in low socioeconomic status households are substantially more likely to have an early birth outside of marriage when the gap between the 10th percentile and the middle of the income distribution is larger, all else

equal. As the level of lower- tail income inequality increases, low socioeconomic status women are less likely to abort their pregnancies. We econometrically consider other aggregate- level variables that might affect an individual’s perception of economic success, such as the absolute level of income at the bottom of the distribution and the college- high school wage premium. We also considered aggregate- level variables that might be spuriously correlated with inequality and teen birth rates and thereby confound the interpretation of our primary results, such as the political leanings or religiosity of a place. The data do not support any of these alternative explanations.

We have proposed a model of young adult decision- making that could potentially explain our empirical fi ndings. The model is built within the economics paradigm of a utility maximizing rational actor and based on the insights of the relevant sociological, anthropological, and ethnographic evidence that has largely gone unexplored in the economics literature. The conceptual link between our empirical results and our sug-gested model is the presumption that greater levels of lower- tail income inequality— which can informally be thought of as a greater gap between the “middle class” and the “poor”—lead to a heightened sense of economic marginalization and despera-tion among those at the bottom of the income distribudespera-tion. Data from the geocoded NLSY79 provide preliminary support for this presumption. In our model, when a poor young woman subscribes to economic despair in this way, perceiving that socioeco-nomic success is likely unachievable to her, she is more likely to embrace motherhood in her current position as there is little option value to be gained by delaying the imme-diate gratifi cation of having a baby. Theoretically, greater levels of income inequality could lead to an “aspirational” effect instead, but the data do not support such a story in this context and are instead consistent with a “desperational” effect.