On: 14 May 2013, At : 02: 57 Publisher: Rout ledge

I nform a Lt d Regist ered in England and Wales Regist ered Num ber: 1072954 Regist ered office: Mort im er House, 37- 41 Mort im er St reet , London W1T 3JH, UK

Current Issues in Language Planning

Publicat ion det ails, including inst ruct ions f or aut hors and subscript ion inf ormat ion:ht t p: / / www. t andf online. com/ loi/ rclp20

Navigating through the

English-medium-of-instruction policy: voices

from the field

Nugrahenny T. Zacharias a a

Facult y of Language and Lit erat ure , Sat ya Wacana Christ ian Universit y , Salat iga , Indonesia

Published online: 10 May 2013.

To cite this article: Nugrahenny T. Zacharias (2013): Navigat ing t hrough t he English-medium-of -inst ruct ion policy: voices f rom t he f ield, Current Issues in Language Planning, DOI: 10. 1080/ 14664208. 2013. 782797

To link to this article: ht t p: / / dx. doi. org/ 10. 1080/ 14664208. 2013. 782797

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTI CLE

Full t erm s and condit ions of use: ht t p: / / w w w.t andfonline.com / page/ t erm s- and-condit ions

This art icle m ay be used for research, t eaching, and privat e st udy purposes. Any subst ant ial or syst em at ic reproduct ion, redist ribut ion, reselling, loan, sub- licensing, syst em at ic supply, or dist ribut ion in any form t o anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warrant y express or im plied or m ake any represent at ion t hat t he cont ent s w ill be com plet e or accurat e or up t o dat e. The accuracy of any

Navigating through the English-medium-of-instruction policy: voices

from the

fi

eld

Nugrahenny T. Zacharias*

Faculty of Language and Literature, Satya Wacana Christian University, Salatiga, Indonesia

(Received 13 August 2012;final version received 5 March 2013)

The aim of this paper is to explore the practice of English-medium-of-instruction (EMI) education in Indonesia implemented within the backdrop of a governmental macro-language planning policy known as International Standards Schools (ISSs) between 2007 and 2013. Twelve teachers teaching at two candidates of ISSs were interviewed to examine their agentive behaviors in responding to the EMI policy. The findings showed that all teachers attempted to use English as much as possible despite their lack of agreement with the policy. In the present study, teachers’ agentive behaviors appear to be affected by the social setting in which the policy takes place. These societal factors are influenced by the complex interplay between teachers’ English competence, students’perceived English competence, and the lack of socialization of the EMI policy. At the end of this paper, pedagogical implications for pre-service teacher education are discussed.

Keywords:International Standard Schools; Indonesia; English medium of instruction; local actors; language policy and planning

Introduction

The effects of globalization and the global spread of English have created a phenomenal demand for the mastery of English around the world. In fact, Hamid (2011) notes that dis-courses connecting globalization, English and national development have led developing nations to enhance their commitment to English. In Indonesia, this commitment was reflected in the establishment of International Standards School (ISS) policy in 2007. The policy generally aimed to transform selected or the‘best of the best’public schools

(Coleman, 2011) to meet international standards. The goal of the ISS policy was ultimately to produce globally competitive students at the primary and secondary levels.

International education is not a new phenomenon in Indonesia. Prior to the ISS policy, there were at least three types of international schools. Thefirst and perhaps the oldest one is one that Coleman (2009a) has termed as‘true international schools’(p. 2) or TISs, for short.

TISs serve the pedagogical needs of children of expatriates working in Indonesia. The tea-chers and students are all expatriates. They rarely open their doors to Indonesian nationals (Coleman, 2011), although recently, Indonesian students were allowed to apply. The second type of international schools were Indonesian private international schools (Coleman, 2011) or IPISs. IPISs serve children of the extremely wealthy Indonesians as well as expatriate children. The third type of international schools is national plus schools. As the name indi-cates, these schools combine the national curriculum with an international curriculum of

© 2013 Taylor & Francis *Email: ntz.iup@gmail.com

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14664208.2013.782797

their choice. The number of national plus schools has grown substantially in the past 10 years (Forde, 2006), but how graduates of these schools perform in terms of national and global competitiveness remains unknown to the general public.

Due to the different types of international school in Indonesia, the notion of ‘

inter-national’attached to public school under ISS policy needs to be defined. The government

has defined ISS as

A national school that prepares the students based on the national educational standards and offers an international standard by which the graduates are expected to have international/ global competitiveness. (‘Sistem Penyelenggaraan’, 2007, p. 3)

Here, the concept‘international’means meeting the national and international standards.

What constitutes international standards is not mentioned in detail other than teaching stu-dents to acquire skills and knowledge to compete globally. In another government docu-ment, the concept of international standard was elaborated as

…the education standards of one member nation of the Organization for Economic Co-oper-ation and Development (OECD) and/or another advanced nCo-oper-ation which has particular strengths in education such that is achieves competitive advantage in the international forum. (Depdi-knas, 2007, p. 7 cited in Coleman, 2009a, p. 10)

Similar to the previous excerpt, the educational standards that Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries and/or other‘advanced nation’have are unclear

nor is it clear if those standards are compatible to one another. Another important point is the extent to which local resources can meet these standards provided that these standards can be clearly defined and measured. To make it more complex, Kustulasari (2009) argues that at present, there is no international organization that can guarantee accreditation of an international school and thus, the accreditation is more likely to be defined and determined nationally. In other words, it is arguable as to whether a school that is accredited as inter-national by government standards might, in fact, have interinter-national qualities in the global job market.

The process of awarding ISS status was relatively straightforward. Potential public schools were nominated by the district government and then were promoted to be candi-dates of ISSs. In 2010, it was estimated that the total number of ISSs at all levels was 874 (Kemendiknas, 2009), which according to Coleman (2011) constitutes only 0.46% of the 190,000 public schools in Indonesia. The development of ISSs indicated that the gov-ernment expected that creating public schools at an international standard would generate more globally competitive graduates who would eventually boost Indonesian’s economy

and national development.

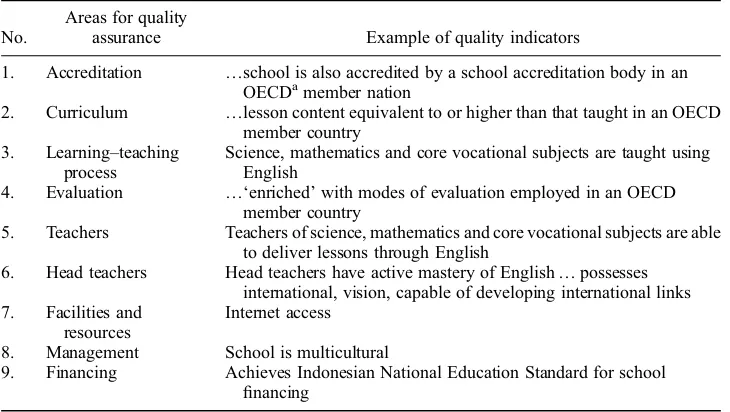

Compared to regular public schools, the budgetary allocations for ISSs were quite gen-erous. These schools were givenfinancial support over six years from the district, provin-cial, and central governments (Republik Indonesia, 2010, article 144 clause 5, and article 146 clause 5). The length of support varied depending on the type of school. If, by the end of the period of support, a candidate of ISS was unsuccessful in fulfilling the required standard, then its status returned to national standard school (Coleman, 2011). Over the period of six years, candidates of ISSs needed to transform their school based on nine key areas as indicated in Table 1.

A language policy that stipulates the use of English as a medium of instruction appears to be the most prominent factor separating ISSs from regular public schools. Thus, in 2009,

teachers of core vocational subjects began to teach what was familiar to them, that is, the content, in a language unfamiliar to them, English. The English-medium-of-instruction (hereafter, EMI) policy was supposed to be implemented in stages (Dharma, 2007) using a somewhat simplified and vague set of guidelines:

. First year: English (25%) and Indonesian (75%) . Second year: English (50%) and Indonesian (50%) . Third year: English (75%) and Indonesian (25%)

While the guidelines may work well for students from a small dominant elite group who are well placed to acquire English, it presents enormous challenges for the majority of Indone-sian students and their teachers who live in rural areas where English is rarely used. It is unclear how the model wouldfill the English gap as there might be students who come from regular schools and/or rural areas where English is not the medium of instruction.

The assumptions underlying the model need be problematized on several levels. First, it is unclear how the 25% or 75% can be neatly measured. Also, the model assumes that all students come to school with an active mastery of Indonesian, which is not the case. In 2000, Gordon (2005) estimated that there were approximately 11% of Indonesians who spoke Indonesian as the first language and 68% who spoke it as a second language. Provided that Gordon’s estimation is correct, then, there are approximately 21% of the

population who only speak their local languages. Since ISSs were implemented in every district in Indonesia, it remains questionable how the EMI guidelines can be implemented in schools with a significant number of students who might only speak minority languages. The EMI guidelines’assumptions for ISS teachers are also unfounded. For a teacher to

be able to manage teaching in English and Indonesian according to the strict measures set by the guidelines entails an advanced level of competence in using both languages, which is

Table 1. Nine areas for quality assurance for ISSs (taken from Depdiknas, 2007, cited in and adapted from Coleman, 2011).

No.

Areas for quality

assurance Example of quality indicators

1. Accreditation …school is also accredited by a school accreditation body in an OECDamember nation

2. Curriculum …lesson content equivalent to or higher than that taught in an OECD member country

3. Learning–teaching process

Science, mathematics and core vocational subjects are taught using English

4. Evaluation …‘enriched’with modes of evaluation employed in an OECD member country

5. Teachers Teachers of science, mathematics and core vocational subjects are able to deliver lessons through English

6. Head teachers Head teachers have active mastery of English…possesses international, vision, capable of developing international links 7. Facilities and

resources

Internet access

8. Management School is multicultural

9. Financing Achieves Indonesian National Education Standard for school

financing

a

OECD, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

quite rare for English–Indonesian bilinguals. As English used by bilinguals is negotiated

around interlocutor and contexts (Zacharias, 2012), such a strict rule of the pedagogical use of English/Indonesian might be unrealistic as students come to ISSs with different levels of mastery of English and Indonesian.

The EMI model also assumes that there are a sufficient number of teachers in every ISS who have an adequate balanced bilingualism in English and Indonesian. Unfortunately, the literature on ISS policy has shown that these assumptions are far from reality. In one of the national leading newspapers,Kompas(Ina, 2012), for example, Muhamad Husnan stated that there were a limited number of ISS teachers who could speak English fluently. Hadi Purnomo (Ina, 2012), an English teacher at Purbolinggo, explained that in his school among the four Mathematics teachers, only one was fluent in English and among four natural science teachers, only two were confident in their English. Among content teachers who spoke English, there were even fewer who were able to teach in English. A study by Stephen Bax from the University of Bedfordshire, England, found that the use of EMI was not effective because only 25% of ISS teachers have the capability to teach in English (Kompas, 2010). This finding is supported by the Head of English Development of British Council, Danny Whitehead. He argued that fluency in English did not positively correlate to competence and skills for using English to teach and manage the classroom.

Finally, the ISS policy has subjected ISS teachers to unpleasant and unwanted attention. ISS teachers suddenly found themselves to be considered incompetent and their previous education inadequate. Therefore, they were trained in countless English‘boot camps’so

that their English teaching competence could meet the standards of ISS. Despite the sub-stantial efforts to upgrade ISS teachers, it remains unknown to what extent these training sessions contribute to teachers’overall English competence and teaching skills.

To date, studies on ISS policy have focused on macro-level policy perspectives (Coleman, 2009a, 2009b; Kustulasari, 2009). Liddicoat and Baldauf (2008) argue that studies on actors in language policy and planning (LPP) are in fact needed as‘it is often

local contextual agents which affect how macro-level plans function and the outcomes that they achieve’(p. 4). One of those local contextual agents is the ISS classroom teachers.

Yet, despite their determining roles, studies focusing on ISS teachers are still relatively scarce. Even when they are done, these studies tend to focus on the English production of these teachers (Astika & Wahyana, 2010; Astika, Wahyana, & Andreyana, 2008). There-fore, there is a need to understand how the policy influences ISS teachers’classroom

prac-tice as well as how teachers respond to and enact the policy.

Focusing on the ISS teachers from two candidates of ISS in Indonesia, SMP X (junior high school X) and SMA X (senior high school X), this paper discusses the classroom prac-tice that is the result of EMI policy. It is my position that it is both useful and productive to try to unravel and to examine what the voices of these ISS teachers have to say as they navi-gate and adapt their teaching to meet the EMI policy. The major research question that the present article addresses is, how do ISS teachers navigate their way through the EMI program and how do they adapt their teaching as a response to the EMI policy guidelines? Data from the present study were collected through semi-structured interviews with 12 par-ticipating ISS teachers working in two candidates of ISSs in a small town in Central Java, Indonesia.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework for this paper is based on a recent trend in LPP emphasizing the role of the teachers’agency and the need to study language policy implementation at the

micro-level or in a localized context (Chua & Baldauf, 2011; Liddicoat & Baldauf, 2008; Martin, 2005; Zhao, 2011; Zhao & Baldauf, 2012). Traditionally, Zhao and Baldauf (2012) maintain that studies of LPP often highlighted teachers as recipients of and submissive to LPP. Their roles were simply as enactors of macro-level policy initiatives. Even when their roles were addressed, they were impersonalized, aggregated, and left in general terms (Kaplan & Baldauf, 1997), thereby, leaving little room for and attention to individual tea-chers’voices and how these teachers realized LPP at the local context.

The attention given to teachers’roles in mediating language policy is important because

no policy is‘transmitted directly and unmodified to local contexts’(Liddicoat & Baldauf,

2008, p. 11). In reality, Bamgbose (2004) notes that when a macro-level decision‘trickles

down to the bottom, contradictory policies are adopted at different levels and what is implemented at a lower level is often different from what is prescribed at a higher level’

(p. 61). To this end, teachers are ‘gatekeepers’ (Liddicoat & Baldauf, 2008, p. 12) and

their roles are transformative, even within the highly constraining policy environment (Hornberger & Skilton-Sylvester, 2000). Therefore, Liddicoat and Baldauf (2008) note that investigating the ways teachers produce a particular language policy in the classroom should be ‘fundamental and integrated part of the overall language planning process’

(p. 15). Tollefson (2006) goes even further arguing that since teachers experience the con-sequence of language policy the most, they should have a major role in contributing to policy decisions.

According to Hornberger and Skiton-Sylvester (2000), teachers’ gatekeeping role is

exercised based on the extent to which they possess or display agency. Pickering (1995) defines agency as‘the ability of individuals to exercise choice and discretion in their

every-day practices’(cited in Ollerhead, 2010, p. 609). For Giddens (1984), teachers activate their

agency when they are able to‘make a difference to a pre-existing state of affairs or course of

events’ (p. 14). In the present study, the‘pre-existing state of affairs’ is contextualized

within the EMI policy and following Ollerhead (2010) teachers’ agency is seen as

con-scious efforts by the teacher to overcome and resist‘feelings of powerlessness and

nega-tivity’(p. 609) experienced as the by-product of the EMI policy.

It is through the lenses of these theoretical frameworks that the agentive behavior of 12 ISS teachers in response to the EMI policy is explored.

The study

I individually interviewed 12 ISS teachers teaching in two ISSs in a small town in Central Java. In an open-ended interview, I asked the teachers about their perceptions of the ISS policy, their experiences in implementing the policy, the extent of different training that they had participated in, and how they coped and navigated through the EMI program and adapted their teaching in response to the ISS language policy. I asked them whether they preferred to be interviewed in English or Indonesian before the interview began. All agreed to use Indonesian as the main medium, with the option of using English when it was appropriate. With open-ended semi-structured interviews, I aimed to understand the way the participants framed the events and the strategies they used to navigate amidst the EMI policy. A protocol was used although the participants were encouraged to elaborate and move the interview in the direction of their choice. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed.

The data from the 12 teacher interviews were analyzed using content analysis. The content analysis was conducted in the following way. A preliminary read-through for the purpose of generating some starting themes was done looking for moments in which

factors constituting teacher identities appeared to emerge in their discourse (Bogdan & Biklen, 1992). Themes emerged throughout the process, requiring a significant amount of backtracking and recoding to ensure that the entire information in the data was reflected. Then, gathering together all the different segments of the themes, I looked for patterns in the way they narrated their experiences, feelings, and opinions surrounding the EMI policy.

There are limitations to the data analysis for this particular case study. With only one interview per participant, contact was brief with each individual teacher. And, although teacher background data were collected, the sample size and sampling method do not allow the study to draw any reasonable conclusions that connect teachers’ background

and their experiences to their perceptions or their self-described practice of English use in the classroom. Furthermore, although I had planned to conduct classroom observations for each teacher, at the point when the research was conducted, the teaching and learning process had already been completed as the last two months were allocated for practice test sessions to prepare students for the national exam.

Teacher voices toward the ISS policy

The majority of teachers were ambivalent when asked if they were excited to have the opportunity to use English in their lessons for reasons such as limited English proficiency and additional workload. Only two teachers, Mr Maman and Ms Sinta were totally excited by the EMI policy. Ms Sinta has been teaching Mathematics in her present school for 11 years. She labeled herself as a strong advocate of EMI and was held up as a model ISS teacher by other ISS teachers and school officials. For her, the use of English to teach Math-ematics helped to reconstruct the image of MathMath-ematics and MathMath-ematics teachers:

All these years Math subjects are considered old-fashioned…meaning the subject is static. For example factorisation is always taught and learned in a certain way. Math is considered‘ ready-made’knowledge. Consequently, the Math teachers are also considered as old-fashioned.… Through EMI, students know that math is a dynamic subject and teachers are not the only source of knowledge. They can learn Math from the Internet. Easier. Before ISS policy, when I taught the width of parallelogram, I only used a ruler and a cutter. Since in ISS we need to use ICT, I learnflash, power point so I can teach the width of parallelogram faster using animation. It becomes more exciting. The students like it even more. (Ms Sinta, 18 July 2012)

From Ms Sinta’s comments it can be inferred that traditionally Mathematics was taught

in a reductionist model wherein the teacher acted as an authority of the ‘ready-made

knowledge’ passing on information to students. Here, the use of English as a

medium of instruction has shifted the role of both the students and teachers. Students are no longer passive recipients of knowledge and empirical information but are now expected to join in the process of making meaning of the knowledge. Teacher’s roles

also have shifted from the utmost sourceof knowledge to one ofthe sources of knowl-edge. The dramatic shift of Mathematics teachers from the only authority to one of the sources of knowledge is significant in Indonesia, where teachers continue to be viewed as transmitters of knowledge.

Despite the majority of teachers’being ambivalent to or in strong disagreement with the

EMI policy, all of them feel obligated to implement the policy. Concepts such as‘a moral

duty’and‘a responsibility’were often cited by teachers when they were asked why they

enact the policy. Accompanying the concepts were obligatory verbs such as‘must’,‘

obli-gated’, and‘have to’; positioning themselves as having little, if not no, option and freedom

to act in other opposing ways. When describing their reaction to the policy, all the participants opted for negative words such as ‘lumpuh’ (crippling), ‘cemas’ (worried), ‘takut’(afraid); simply because all of the teachers are doubtful of their English oral

profi-ciency, but somewhat confident of their (passive) English competence related to the subject matter.

Among all the participants, perhaps, Mr Yono voiced the strongest opposition to the policy. He feared the use of English might threaten national unity and professional authority:

If we talked about the EMI policy, it relates to the dignity of our nation. I don’t think inter-national quality needs to be in English. One of the purposes of ISS is to open doors for foreigners to study here [in Indonesia]. That’sfine but the foreigners need to learn Indonesian so they know Indonesian culture. So foreigners need to obey our rules not us serving them with the use of English. Even if we use English, the foreigners will make fun of our English. They won’t understand our English. Therefore, foreigners need to study Indonesian. The content subjects need to be delivered in Indonesia but that’s just my personal opinion. (Mr Yono, 25 June 2012)

What I found interesting from his comments is that, despite the growing literature promot-ing English as an Asian language (Graddol, 2006; McArthur, 2003) or the language of its users (Jarvis, 2005; Norton, 1997), Mr Yono continues to perceive English as the other language. He sees the use of English in teaching as equal to‘serving’foreigners. Even if

he did teach in English, he was doubtful if his English would be acceptable to these foreigners. In addition, he viewed teaching Physics in a language other than Indonesian as a threat to his professional authority as a Physics teacher. He felt his competence in teach-ing physics would be threatened and obscured by his Indonesian-accented English, which, he believed, would be ridiculed by foreigners.

Despite Mr Yono’s uneasiness about the policy, he not only attempted to implement the

policy but used English as much as possible in the lesson. When asked why he enacted the policy, he responded:

EMI policy is just a policy. So, it can be said that I am just trying to fulfill my responsibility as a civic servant. If the government says we need to be like this, I try my best to do so. If we have to teach in this way, I try to teach in that way. I try to teach as expected [using English]. I try my best even though I do not support it wholeheartedly but like I say, it is a policy so just do it. Try to give my best as expected by the government. It’s as simple as that so just keep on trying…. (Mr Yono, 25 June 2012)

For Mr Yono, using English in teaching Physics is a part of enacting his civil servant responsibilities, that is, following the directions of the central government (‘if the

govern-ment says we need to be like this, I try my best to do so. If we have to teach in this way, I try to teach in that way’). Therefore, he defines his‘best’effort not in terms of improving the

teaching and learning process, but behaving according to the government standards and expectations (‘Try to give my best as expected by the government’), although it goes

against his own belief.

For those who are hesitant to follow the EMI policy, they respond in a way that avoids drawing attention to themselves. Ghazali, Hafidz, and Saliwangi (1986) note that one of the strategies of government employees to respond to unwanted policy is not to challenge the policy openly but to remain quiet and unobtrusive. This is evident in the case of Ms Warni, a Mathematics teacher. Ms Warni has only been in the present school for less than a year. She was relocated from another state school in a similar town. When she heard, she was being

moved to the present school, she was terrified because she knew she would be expected to teach Mathematics in English.

Her fear was exacerbated because she did not receive any guidelines from the prin-cipal explaining when and how much English she was expected to use. She, then, took the initiative to ask the vice principal and voiced reservations about the EMI policy. To her surprise, the vice principal stated that simply sandwiching the lesson with a greeting and a closing was sufficient. In the interview, she honestly stated that she made an effort to use English much more than expected. For her, simply sandwiching the lesson with an English greeting and closing was not what she believed the EMI policy should be.

During thefirst three months, she admitted feeling stressed out to the point that she lost a significant amount of weight. That critical incident led her to make a conscious decision to redirect her energy from English to teaching and assisting the students:

I was still confused why I was being reallocated to this school. So I just teach. Just that. If I am not good enough [in teaching], because of my limited English use, I am ready to be reallocated to another state school.Pasrah.…that thinking comforts me. There were times when I was stressed out thinking about how and when I should use English…the first 2–3 months I was here. But then, I was thinking I cannot continue my life like this…it negatively affects my teaching. I decide to focus on my teaching and less on the use of English. The important thing is the students understand. (Ms Warni, 15 June 2012)

Ghazali et al. (1986) note that civil servants are often concerned that if they make a mistake or considered unfaithful, they will be transferred to a less desirable location or position. In the case of Ms Warni, her fear of not measuring up to the government standards of English use has taken its toll on her personally (i.e. weight loss) and on her teaching. The use of the word ‘pasrah’, a Javanese cultural concept illustrating self-reliance, despite one’s best

effort, to wherever destiny brings them, positions herself as having no control over her destiny; thus, she is ready to be reallocated if deemed unfaithful and unloyal by the central government for not using English as much as expected.

The narratives of teachers in this section illustrate that the majority of teachers found themselves under considerable moral pressure to enact the policy based not on their own best judgment of the policy but solely on preconceptions of what they perceived as accep-table to the school and/or the government.

Teachers’stated teaching strategies in negotiating the EMI policy

Coleman (2009b) states that the practice of English use across ISSs varies. Interestingly, the data collected through the interviews show that the stated classroom practice with regard to English use is highly varied even within the same school. The teachers have different ideas on how much English they were expected to use in the classroom. The socialization that they received from the principals of each school seems to be hazy. All of them understood that they were expected to use English as much as possible, although not necessarily exclusively.

Despite the poor dissemination of the policy, ISS teachers seem to navigate their way under a shared and generally understood language policy that exists in tacit classroom prac-tices and the interactions between teacher and students. Under such conditions, teachers develop creative strategies negotiated around teachers’English oral proficiency, students’

English competence, the role of ISS teachers, and the purpose of learning. The following are the strategies that teachers stated they used in coping with the policy.

Centralizing English input through the use of ICT

Other than the use of English, another requirement of ISSs is the need to incorporate inter-net and communication technology (ICT) in teaching. Since the establishment of the ISS policy, both the junior and senior high schools were able to facilitate teaching in the class-room with an LCD projector and a laptop. The government at both the district and national levels hold training sessions in the use of power points, blogs, and other software to enhance the teaching and learning of content subjects. Prior to receiving the ISS grant, almost all teachers in the two state schools admitted to barely‘using’a computer, much

less educational software or the Internet. The audio-visual aids commonly found in the classroom were whiteboards. After the policy, all the teachers indicated that they made their best effort so that the inputs (worksheet, power point slides, and assessment) were in English. When the present study was conducted, all the teachers claimed that all the written input in their classes were in English.

For many of these teachers, they said they compensated for their lack of English by providing notes in English on the power point slides. These power point slides appeared to be the major English inputs used in the classroom. During thefirst year of implement-ing the ISS policy, many teachers used their spare time, in the words of Mr Yono,

‘working like a horse’ summarizing, paraphrasing, and translating the textbooks onto

power point slides. These teachers are also able to navigate their way through ICTs in ways that benefit them. Mr Yono, for example, was aware that rather than writing points in his slides, he wrote more elaborated points so that he did not need to recall words in English. Both Mr Maman and Mr Yono consciously tried to write as little as possible on the whiteboard to avoid misspellings which were more likely to occur when they wrote in English.

Many teachers use translating gadgets such as Google Translate or‘Alfalink’(a

calcu-lator-like bilingual dictionary) when summarizing the textbook in a power point. Mr Eko, a teacher ofBasic Computer Science, perhaps, is the only teacher who made a personal tech-nology leap by buying a Samsung X2 so that he could install the Google Translate appli-cation, although he could barely afford it on his current salary. When asked how technology aided his English use, he explained:

When I teach, I open google translate in my desktop. So whatever I want to say to the students, I type it into the google translate. I like google translate because it also includes the pronuncia-tion. So, it helps me. Especially when the electricity is down and I cannot use my desktop. That’s why I buy this phone. Too expensive for me, actually. So I can just type the phrase/ word I wanna say in Indonesian and then, I can see and listen how to say it. For example ‘pindah ke atas’ [let’s move upstairs]. But the problem is when there is a connection problem, then I use Indonesian. (Mr Eko, 2 April 2012)

Here, I found Mr E’s buying Samsung X2, a phone that is way above his pay grade, as an act

in activating his agency in surviving the EMI policy. It helps him to navigate his teaching around the expectation to use English as well as local constraints (occasional power blackouts).

Surviving the EMI policy through code-switching into Indonesian

Teachers claimed that students do not have the necessary English competence to cope with the EMI policy. Therefore, it is a common practice for teachers to provide a glossary at the beginning of a new topic. During the interview, Ms Grace stated that by introducing new vocabulary before teaching a topic, she expected learners would understand when new

words occurred in context. Other than using a glossary, teachers commonly provide stu-dents with a summary in English and then shared it through the power point slides. However, the way teachers scaffolded these English summary varied. Some teachers conduct the lesson entirely in Indonesian with the only English being chunks of text read from the slides or occasionally slipping in English terminology. Others used English for classroom use such as greetings and closings, collecting papers, and reprimanding unwanted behavior. Only a very few teachers used English all the time.

What they all have in common is that they switched into Indonesian to scaffold under-standing and important concepts. This is best summarized by Mr Yono when I asked him to explain his reasons for choosing Indonesian to reinforce concepts in Physics:

The target of the policy is to use English all the time. But we teach concept and we cannot teach it wrong. So, concepts need to be delivered in Indonesian. Must be in Indonesian…concept. When using jargons, yes, we can use English. But when we highlight concepts it needs to be in Indonesian. Because if we use English, we are afraid we represent the concept inappropriately. So each time I teach concepts such as Archimedean. If I use English, it is even difficult for me, let alone, the students. So I might be teaching the wrong concept. (Mr Yono, 25 June 2012)

Mr Yono seems to perceive his lack of proficiency in English as a barrier to knowledge. He was aware that when teaching, the wrong choice of words in the foreign language may lead to comprehension issues. Since language is the carrier of content (Tatzl, 2011), teachers’

linguistic competence is crucial in the success of EMI policy.

Code-switching into Indonesian is not without its drawbacks. As a consequence of extended clarification in the students’mother tongue, the EMI policy tends to accommodate

less content compared to native language lectures. One participant, Ms Rani, a Chemistry teacher in the senior high school, mentioned that teaching in a foreign language involved a slower acquisition rate for the content delivered:

EMI is good but we need tofinish the scheduled material for the national examination. Since we need to explain the materials twice. Giving input in English and then, translated them into Indonesian. So materials that were usually can be covered in one hour. Now we need at least two hours. Longer. Also, if we want to use all English that means more preparation time of the teacher. That is difficult because we are teaching twenty four hours per week in addition to other administrative work. (Ms Rani, 16 July 2012)

Ms Rani’s comment was echoed by all teachers when they were asked why they did not use

English. Inferred from her comment is that teaching and learning through the medium of a poorly acquired medium of instruction is time-consuming. As a result, she frequently did not complete the syllabus set by the national government (Othman & Saat 2009; Probyn, 2005; Tatzl, 2011).

Ball (1994) notes that language policies are often‘introduced into contexts where other

policies are in circulation, and that the enactment of one may inhibit or contradict or infl u-ence the possibility of enactment of others’(p. 19). Through Ms Rani’s comment, it is clear

that she was caught between her allegiance to her institution and her moral responsibility to the students. On the one hand, she needed to use English. As a civil servant, she felt obliged to do what her institution has decided to do, that is, enacting the EMI policy. On the other hand, she felt a moral responsibility to help students pass the national examination written in a language different from the medium of instruction. In Indonesia, students are assessed through national examination at the end of every academic year. The grades obtained from the national examination will later be used for further education and/or in the job market.

And thus, she felt that her continued use of English may hamper students’understanding of

the course content and eventually might sacrifice students’success in the national

examin-ation. For this reason, she made a conscious decision to limit her English use and opt for the use of Indonesian, the language she felt students would be more comfortable with.

It is interesting to note that these teachers use Indonesian strategically. All teachers admitted to using far less of the national language when they are being observed by gov-ernment/school officials (Probyn, 2002). This is best summarized by Ms Nani, a Biology teacher, at the senior high school:

When we were supervised, I used almost all English. So I picked the materials that are easy. For example, about nitrate recycling process. So I usually used visual with English words so it guided me when I explained the materials although I was notfluent. But that was when I was supervised. More English. Usually I just slipped English words/jargons into my teaching. (Ms Nani, 1 July 2012)

Implied in her comment is the assumption that ideal EMI classes employ all English and that the use of first language in the EMI policy is often seen as bad practice by the policy-makers. In the case of Ms Nani, she made a deliberate decision to adjust the content to her English competence and used visuals that allowed her to use more English. Her decision seems to be informed by political reasons rather than educational ones. She felt it was her moral responsibility to satisfy the supervisor with what she per-ceived as an ideal situation for the EMI classroom. Although many might question Ms Rani’s strategy in surviving the supervised EMI classes (e.g. Martin, 2005), Brock-Utne

(2005) argues ‘while we are waiting for ideal situation to happen, teachers must be

allowed to code-switch because their speech behavior is sometimes the only possible com-municative resource there is for the management of learning’(p. 190).

Negotiating the EMI policy through expressing linguistic vulnerability

Not only were the teachers well aware of their limited English, but they were also honest about it in front of their students. In fact, they made it one of their strategies to keep on reminding the students of their inadequacy in speaking English. During thefirst weeks, when the EMI policy was implemented, Ms Warni said‘We are learning together. Like

you, my English is not good.’ The way Ms Warni positions herself as a learner of

English is a common strategy used by many teachers. As in the case of Ms Grace:

My problem when I speak English in the classroom is sometimes my mind goes blank. Sud-denly, I am struggling tofind the English words of something. I totally forgot even the simplest thing. Then, I just asked my students‘What is this in English?’And then, one or two students will say,‘Eraser, Mam.’The students are great. They are smart. Their English sometimes are better than the teachers. (Ms Grace, 7 May 2012)

This narrative shows that in an attempt to survive the EMI policy, ISS teachers have made a conscious choice to make students collaborators in creating linguistic input. In the case of Ms Grace, she saw students, who she believed as‘great’and‘smart’, as learning partners

who she might resort to from time to time when she needs linguistic guidance.

However, not all teachers were confident in making students’their linguistic learning

partners. Mr Dono, for example, often felt frustrated because when he spoke English, the students often laughed at him. This certainly made him hesitant in using English. When asked how he overcame his English inadequacy, Mr Dono shared the following:

Before starting the lesson, I often say to my students‘My grammar is terrible. That’s why I will just talk and not focus on my grammar. The important thing is you know what I am saying.’ That’s what I often said. Just to let them know. I understand English related to Physics, I just do not know how to say it in English.…the students are better in speaking English. Some-times when I wrote test items, students laughed at my English and said‘Sir, the grammar is wrong. I usually said jokingly,“Didn’t I say not to focus on my grammar? The important thing you understand the meaning.”’(Mr Dono, 25 June 2012)

Here, it can be seen that Mr Dono’s strategies in navigating the EMI policy are by shifting

the focus from teaching to communication. He was well aware of his limitations in teaching Physics in English and thus attempted to refocus students’attention from correct language

use to meaning-making. He felt if the students’understand the meaning, then he was

suc-cessful in achieving the purpose of the lesson despite his poor command in English grammar.

What these narratives have in common is that the EMI policy has created a feeling of solidarity on the part of the students, which in turn has been reinterpreted and appropriated as a resource for language reinforcement for the teachers’lack of English proficiency. By

doing so, it has transformed the relationship between students and teacher from a perceived vertical relationship into a more participatory type of interaction. In other words, the policy allows the teacher and students to co-construct the lesson and the language used in it.

Conclusion

Through a content analysis of the interview transcripts of 12 teachers, the study offers insights into how 12 ISS teachers implemented a macro-language policy in two candidates of ISSs in Indonesia. This study purposely places an emphasis on local actors, because the literature on ISS policy in Indonesia largely focuses on the macro-level perspective. Even when local actors are addressed, they are usually seen reductively, based on their lack of teaching competence, English skills, and low TOEFL scores. Indeed, Baldauf, Li, and Zhao (2008) note that when it comes to implementing language policy, it is the language teachers who are ‘gatekeepers’(p. 234) of the policy and not the language planners or

policy-makers.

The interview data illustrate that teachers’ attempts to use English in the classroom

should not be mistakenly interpreted as indicative of support for the EMI policy. Rather, it is a way to enact their civic duty as government officials. Bjork’s (2005) ethnographic

fieldwork in six junior high schools in East Java showed that public servant teachers primar-ily are evaluated based on their allegiance and obedience to the central government and not on the education they provide. Bjork (2005) argues that civil servant teachers have learned from experience that the emphasis up to now has been on teachers as government employ-ees rather than as professional educators. Consequently, personal voices and opinions are seen as irrelevant and even unnecessary because with regard to educational policy, ‘the

system did not value their opinions…the basic educational functions of schools were

deter-mined in Jakarta [central government] and would not be modified based on the suggestions of classroom instruction’(Bjork, 2005, p. 101). Therefore, civil servant teachers have been

conditioned to follow orders (or policy) from the central government rather than to actively participate in shaping them.

In the light of Bjork’s study, teachers’efforts to implement the EMI policy in the present

study might seem to be best interpreted as agentless. In fact, the act of reproducing the policy can be seen as an act of activating agency in itself. As pointed out by Mr Maman, Ms Grace, and Ms Warni, their efforts to implement the policy were ways to increase the

economic stability of their workplace, the schools, and ensure the sustainability of their jobs. As government officials, they were all aware that failure to at least show initiative to implement the policy might jeopardize their future careers.

From the interviews, teachers’agentive behaviors appear to be affected by the social

setting in which the EMI policy takes place (Ollerhead, 2010; Toohey, 2007). Here, the societal factors are influenced by the complex interplay between teachers’English

compe-tence, students’perceived English competence, and the lack of socialization of the EMI

policy. It seems that the poor, if not absent, socialization process ISS teachers received from the principal of the school and/or the government provided them with the pedagogical freedom to develop their own classroom teaching techniques to meet the needs of the stu-dents and to survive the EMI policy.

One of those teaching techniques is the use of Indonesian to compensate for the lack of English of both teachers and students. Martin (2005) labels the strategy as‘safe’practices

(p. 89), that is,‘practices that allow the classroom participants to be seen to accomplish

lessons’ (p. 89). The safe practice that many of the teachers use to annotate crucial

subject-related concepts is a convenient way to negotiate their limited English proficiency that might otherwise be sacrificed if teachers insisted on using the required medium of instruction. Although the safe practices are the common stated classroom practices, Martin (2005) argues that safe practices such as the one Mr Yono and most teachers in this study used might undermine the policy and can hamper the acquisition of English, denying the very essence of EMI policy. Othman and Saat (2009) claim that teachers’

code-switching into a language they have a greater access to might indicate a lack of com-petence both in the language of instruction or in pedagogical knowledge of using the language of instruction in integrating content and knowledge.

Thefinding is not surprising as these teachers did not receive sufficient training on how to integrate the teaching of English as a second language with science instruction at high schools. The training that they received was only dealt with daily English and not the English for the specialized purpose related to their subject matter. Therefore, in the class-room, these teachers continue to struggle when conveying concepts which require distinct vocabulary and technical terms that are meaningfully unique to scientific contexts. Accord-ing to Martin (2008), for actors at the operational level to work for the language policy, tea-chers need to be equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills to enact the policy. Thus, continued efforts need to be taken to strengthen teachers’content-specific language

skills.

Several studies indicate that when navigating through the EMI policy, teachers such as the ones in the present study perceive code-switching as unacceptable rather than as a valid linguistic strategy (Adendorff, 1996; Setati, Adler, Reed, & Bapoo, 2002). In the present study, all the participating teachers consciously attempted to use all English when being observed. In this regard, Probyn (2005) notes that teachers’ code-switching need to be

recognized as a legitimate classroom strategy. Therefore, it needs to be strategically woven into the classroom practice to optimize content learning. In this regard, training for ISS teachers needs to plan for teaching strategies which coherently and strategically integrate learners’home language.

In this paper, it only has been possible to explore the voices of 12 local actors at two candidates of ISSs in Indonesia. It needs to be noted that during thefinal revision of the present paper, the ISS policy was terminated following a Constitutional Court ruling on 8 January 2013. According to this ruling, ISSs need to be terminated immediately because the policy provides unequal access to quality education (Aritonang, 2013). Although the ISS policy has ended, it does not mean that the practice of EMI policy ends as the use of

EMI for teaching Science and Mathematics continues to be pervasive in Indonesia. Therefore, the present study still can provide insights into teachers’ pedagogical

strat-egies into surviving an EMI policy. Teachers’stated pedagogical strategies and agentive

behaviors drawn from the present study can offer insights for pre-service teacher edu-cation program which are used to train content teachers. It is my hope that the findings will be followed by future research, thus providing more dynamic insights into how language planning and policy decisions are being arrived at and are accepted at the grass-roots level.

Notes on Contributors

Nugrahenny Tourisia Zacharias is a teacher-educator at a pre-service Teacher Education at the Faculty of Language and Literature, Satya Wacana Christian University, Indonesia. She obtained her Ph.D. in Composition and TESOL from Indiana University of Pennsylvania, US in 2010. Her research interests are in the areas of identity issues in teacher education, curriculum and material development, EIL pedagogy and the implementation of EMI policy.

References

Adendorff, R. D. (1996). The functions of code switching among high-school teachers and students in Kwazulu and implications for teacher education. In K. M. Bailey & D. Nunan (Eds.),Voices from the language classroom: Qualitative research in second language education (pp. 338–406). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Aritonang, M. S. (2013). Int’l-standard schools must disband by April.The Jakarta Post. Retrieved from http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2013/01/14/int-l-standard-schools-must-disband-april. html

Astika, G., & Wahyana, A. (2010).Model pembelajaran MIPA bilingual dalam rangka mendukung keberhasilan program sekolah bertaraf internasional di Jawa Tengah [A language learning model for bilingual content teachers to support the success of ISS program in Central Jawa]. Unpublished Research Report, Satya Wacana Christian University, Indonesia.

Astika, G., Wahyana, A., & Andreyana, B. (2008).Kemampuan Bahasa Inggris guru SMA Negeri 1 dan SMK Negeri 2 Salatiga dalam mendukung program SBI [The English Competence of Bilingual Teachers at SMA Negeri 1 and SMK Negeri 2, Salatiga to support International Standard School program]. Unpublished Research Report, Satya Wacana Christian University, Indonesia.

Baldauf, R. B., Jr., Li, M.-L. & Zhao, S.-H. (2008). Language acquisition management inside and outside of school. In B. B. Kachru, Y. Kachru, & C. L. Nelson (Eds.),Handbook of educational linguistics(pp. 233–250). New York, NY: Springer.

Ball, S. J. (1994).Education Reform: A critical and post-structural approach. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Bamgbose, A. (2004). Language planning and language policies: Issues and prospects. In P. G. J. van Sterkenburg (Ed.),Linguistics today: Facing a greater challenge(pp. 61–88). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Bjork, C. (2005).Indonesian education: Teachers, schools and central bureaucracy. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. (1992).Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and qualitative methodology. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Brock-Utne, B. (2005). Language-in-education policies and practices in Africa with a special focus on Tanzania and South Africa. In A. M. Y. Lin & P. W. Martin (Eds.),Decolonisation, globalization: Language-in-education policy and practice(pp. 175–195). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. Chua, S. K. C., & Baldauf, R. B., Jr. (2011). Micro language planning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.),Handbook

of research in second language teaching and learning(Vol. II, pp. 905–923). London: Routledge. Coleman, H. (2009a, May 19).Are‘International Standard Schools’really a response to globaliza-tion?Paper presented at the International seminar‘Responding to global education challenges’. Universitas Negeri Yogyakarta, Indonesia.

Coleman, H. (2009b, June 9–11).Teaching other subjects through English in three Asian nations: A

review. Paper presented at the British Council Symposium on English Bilingual Education, Jakarta.

Coleman, H. (2011). Allocating resources for English: The case of Indonesia’s English medium inter-national standard schools. In H. Coleman (Ed.),Dreams and realities: Developing countries and the English language(pp. 87–113). London: British Council.

Depdiknas (Departemen Pendidikan Nasional). (2007).Pedoman penjaminan mutu sekolah/madra-sah bertaraf internasional jenjang pendidikan dasar dan menengah[Quality assurance handbook for primary and secondary level international standard schools/Madrasahs]. Jakarta: Direktorat tenaga kependiikan, direktorat jendral peningkatan mutu pendidik dan tenaga kependidikan, Departemen Pendidikan Nasional.

Dharma, S. (2007). Sekolah Bertaraf Internasional [International Standard Schools]: Quo Vadiz [Electronic Version]. Retrieved May 19, 2012, from http://www.ask.com

Forde, D. (2006, January 10). Who we are. Retrieved March 3, 2009, from http://www. sampoernafoundation.org/content/view/504/126/lang,en/

Ghazali, A. S., Hafidz, W., & Saliwangi, B. (1986).Etos kerja pegawai negeri[The work ethics of civil servants]. Jakarta: Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia (LIPI).

Giddens, A. (1984).The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gordon, R. G., Jr. (Ed.). (2005).Ethnologue: Languages of the world (15th ed.). Dallas, TX: SIL International.

Graddol, D. (2006).English next. Plymouth: British Council.

Hamid, M. O. (2011). Globalisation, English for everyone and English teacher capacity: Language policy discourses and realities Bangladesh. Current Issues in Language Planning, 11(4), 289–310.

Hornberger, N., & Skilton-Sylvester, E. (2000). Revisiting the continua of biliteracy: International and crucial perspectives.Language and Education,14, 96–122. doi:10.1080/09500780008666781 Ina. (2012). Kualitas Guru Jadi Kendala RSBI [Electronic Version].Kompas.Com. Retrieved May 1,

2012, from http://www.kompas.com/read/xml/2010/11/23/09482220/Kualitas.Guru.Jadi.Kendala. RSBI

Jarvis, H. (2005). Technology and change in English Language Teaching (ELT).Asian EFL Journal,

7(4), 213–227.

Kaplan, R. B., & Baldauf, R. B., Jr. (1997). Language planning: From theory to practice. Philadelphia, PA: Multilingual Matters.

Kemendiknas. (2009). Statistik Pendidikan 2007–2008 [Education Statistics 2007–2008]. Jakarta: Kementrian Pendidikan Nasional [Ministry of National Education].

Kompas.com. (2010, November). Bahasa asing di RSBI tidak efektif [The foreign language in ISSs is not effective]. Retrieved from http://www.kompas.com/read/xml/2010/11/12/04063954/Bahasa. Asing.di.RSBI.Tidak.Efektif

Kustulasari, A. (2009).The international standard school project in Indonesia: A policy document analysis. Unpublished MA thesis, The Ohio State University.

Liddicoat, A. J., & Baldauf, R. B., Jr. (2008). Language planning in local contexts: Agents, contexts, and interactions. In A. J. Liddicoat & R. B. Baldauf, Jr. (Eds.),Language planning and policy: Language planning in local contexts(pp. 3–17). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Martin, P. (2005).‘Safe’language practices in two rural schools in Malaysia: Tensions between policy and practice. In A. M. Y. Lin & P. Martin (Eds.),Decolonisation, globalisation: Language-in-education policy and practice(pp. 74–97). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Martin, P. (2008). Educational discourses and literacy in Brunei Darussalam. The International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism,11(2), 206–225.

McArthur, T. (2003). English as an Asian language.English Today,19(2), 19–22.

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English.TESOL Quarterly,31, 409–429. Ollerhead, S. (2010). Teacher agency and policy response in the adult ESL literacy classroom.TESOL

Quarterly,44(3), 606–618.

Othman, J., & Saat, R. M. (2009). Challenges of using English as a medium of instruction: Pre-service science teachers’perspective.The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher,18(2), 307–316. Pickering, L. (1995).The mangle of practice: Time, agency, and science. Chicago, IL: University of

Chicago Press.

Probyn, M. (2005). Language and the struggle to learn: The intersection of classroom realities, language policy, and the neocolonial and globalisation discourses in South African schools. In A. M. Y. Lin & P. W. Martin (Eds.), Decolonisation, globalisation: Language-in-education policy and practice(pp. 153–172). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Probyn, M. J. (2002, July 8–10).Language and learning in some Eastern Cape science classrooms. Paper presented at the SAALA/LSSA conference, Pietermaritzburg.

Republik Indonesia. (2010).Penjelasan atas peraturan pemerintah no.17 tahun 2010 tentang penge-lolaan dan penyelenggaraan pendidikan[Clarification of government decree no. 17, 2010, on management and implementation of education]. Retrieved from http://sa.itb.ac.id/Ketentuan% 20Lain/PP66-2010.pdf

Setati, M., Adler, J., Reed, Y., & Bapoo, A. (2002). Incomplete journeys: Code-switching and other languages practices in Mathematics, Science and English language classrooms in South Africa.

Language and Education,16(2), 128–149.

Sistem penyelenggaraan sekolah bertaraf internasional untuk pendidikan dasar dan menengah, direk-torat jendral manajemen pendidikan dasar dan menengah [The implementation guidelines of international standard school for elementary and secondary education, Directorate general of primary and secondary education management]. (2007). Retrieved from http://gurupembaharu. com/home/download/Panduan-Penyelengarakan-RSMABI-2009.pdf

Tatzl, D. (2011). English-medium masters’ programmes at an Australian university of applied sciences: Attitudes, experiences and challenges. Journal of English for Academic Purposes,

10, 252–270. doi:10.1016/j.jeap.2011.08.003

Tollefson, J. W. (2006). Critical theory in language policy. In T. Ricento (Ed.),An introduction to language policy(pp. 42–59). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Toohey, K. (2007). Autonomy/agency through socio-cultural lenses. In A. Barfield & S. Brown (Eds.),Reconstructing autonomy in language education(pp. 231–242). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Zacharias, N. T. (2012). EFL students’ understanding of their multilingual English identities.

Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching (e-FLT),9(2), 233–244.

Zhao, S. (2011). Actors in language planning. In E. Hinkel (Ed.),Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning(Vol. II, pp. 905–923). London: Routledge.

Zhao, S., & Baldauf, R. B., Jr. (2012). Individual agency in language planning: Chinese script reform as a case study. Language Problems & Language Planning, 36(1), 1–24. doi:10.1075/ IpIp.36.1o1zha