Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

And Who Will Teach Them? An Investigation of the

Logistics PhD Market

Susan L. Golicic , L. Michelle Bobbitt , Robert Frankel & Steven R. Clinton

To cite this article: Susan L. Golicic , L. Michelle Bobbitt , Robert Frankel & Steven R. Clinton (2004) And Who Will Teach Them? An Investigation of the Logistics PhD Market, Journal of Education for Business, 80:1, 47-51, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.80.1.47-51

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.80.1.47-51

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 22

View related articles

n the early 1990s, doctoral students in the disciplines of marketing and logistics found themselves facing very uncertain futures. The labor market for newly minted PhDs was extremely tight. In response, many doctoral pro-grams that offered logistics degrees sharply curtailed their enrollments. However, immediately thereafter, the industry began aggressively courting both undergraduate and graduate stu-dents with degrees in logistics, materi-als management, and similar fields. In response to this demand, new logistics and supply-chain management pro-grams were announced at several insti-tutions (e.g., the University of Louisville and the University of Alaska-Anchorage). In addition, position announcements in marketing and man-agement departments began to list logis-tics, distribution, or supply-chain man-agement as desirable focus areas for applicants.

The rise in demand now appears to have outstripped supply. According to our observations of the past several years, a dearth of qualified applicants is avail-able to fill the open positions. Equally important, anecdotal information sug-gests that the situation is unlikely to change anytime soon because of limited logistics and supply-chain doctoral pro-gram enrollments. Our objectives in this study were to (a) examine recent and

pro-jected future demand to determine if a supply–demand imbalance exists and if it will continue into the future and (b) examine factors affecting logistics doc-toral program recruitment and enrollment for correction of an imbalance.

Logistics Education Review

Logistics doctoral education in the United States historically has been dominated by a small number of “tradi-tional” universities: Arizona State Uni-versity, University of Arkansas, Univer-sity of Maryland, Michigan State University, Ohio State University, Penn-sylvania State University, and the Uni-versity of Tennessee. At each of these universities, the logistics area usually has been part of a broader department— most often in conjunction with market-ing. This administrative structure

reflects the realities of a developing dis-cipline: An extremely limited number of logistics or transportation programs existed before 1990.

In the late 1990s, industry interest in logistics and supply-chain management, combined with an expanding and robust American economy, had companies scouring campuses for new hires. Although the recent economic slump has dampened industry demand some-what, the academic situation is not expected to change soon, as undergrad-uate enrollment is expected to increase approximately 20% to over 15 million from 1998 to 2010 (U.S. Department of Education, 2000). Over the past few years, the number of Graduate Manage-ment Admission Tests (GMATs)— required for a master’s or doctorate in business—has leveled off to approxi-mately 100,000 (Graduate Management Admission Council, 2000); however, the number of MBA degrees awarded has skyrocketed to 97,000 (AACSB, 1999). Although these numbers repre-sent the general business population, one reasonably can project that these trends apply to logistics and supply-chain management.

In response to industry demand, a number of American universities devel-oped new logistics and supply-chain management programs in the 1990s and early 2000s (e.g., the University of

And Who Will Teach Them?

An Investigation of

the Logistics PhD Market

SUSAN L. GOLICIC L. MICHELLE BOBBITT ROBERT FRANKEL STEVEN R. CLINTON

University of Oregon Bradley University University of North Florida University of New Orleans Eugene, Oregon Peoria, Illinois Jacksonville, Florida New Orleans, Louisiana

I

ABSTRACT.At a time when there is high demand for logistics/supply-chain education at the undergraduate and master’s levels, there is short sup-ply of logistics PhDs to take faculty positions. In this research, the authors used both primary and secondary research to confirm the gap between supply and demand of logistics/ supply-chain scholars. Their study draws attention to this salient issue and offers suggestions as to how the disci-pline can monitor and manage the pro-duction of logistics/supply-chain PhDs to bridge the supply and demand gap.

Oklahoma, the University of Wisconsin, Syracuse University, etc.). In addition, many marketing and management departments developed or increased their course offerings in the area of logistics and supply-chain management. Given this increased interest, logistics academics were suddenly in higher demand. However, as most logistics doctoral programs were severely reduced in the mid-1990s—and with a minimum lead time of 4 years—many positions simply could not be filled.

In Table 1, data taken from the most recent Council of Graduate Schools and National Opinion Research Center reports (2001) show the downward trend of business doctoral degrees awarded, particularly those in subfields pertaining to logistics, from 1994–95 to 2000–01. This general slump in supply was accompanied by an overall increase in demand. For example, in 1998–99 there were 1.4 average openings per doctoral graduate in AACSB member schools; in 1999–2000 (assuming no change in the number of degrees grant-ed), this number increased to 2.1 (Grad-uate Management Admission Council,

2000). Although there were no specific numbers identified for logistics, the numbers for the departments typically hiring logistics PhDs (marketing, opera-tions management, and other) were 1.3 average openings per graduate in 1998–99 with an expected increase to 2.0 in 1999–2000.

The Logistics Academic Hiring Sur-vey conducted annually by Ohio State University (Cooper, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003) also reinforces the difference between supply and demand with respect to logistics PhDs. In Table 2, we summarize the number of positions open for entry-level faculty members and the number of logistics graduates entering the market. This difference largely can be attributed to the demand for faculty members with a specialty in logistics at institutions such as Iowa State University, Western Michigan University, and The Naval Postgraduate School—schools other than the “tradi-tional” seven. Such universities con-tribute to the demand for, but not the supply of, logistics scholars.

Why is the number of business PhDs decreasing when the job market seems

so attractive? According to the educa-tion literature, the two primary factors are time and money (Petr & Wendel, 1998). The cost of obtaining a PhD is considerable owing to the long period of time involved. This cost includes not only out-of-pocket expenses but also income that would have been earned had the student remained employed (U.S. Department of Education, 2000). In addition to the financial costs, stu-dents sacrifice time otherwise spent with family or in leisure pursuits and postpone other goals in life to pursue a doctoral degree (Fleming, 1998–99). Although most programs defray the tuition costs, prospective students also must consider costs of living for them-selves and often for other family mem-bers. This factor plays such a large role that it not only affects the choice of institution; it also may reverse the deci-sion to attend at all. Even if a student is recruited successfully and begins a PhD program, there is no guarantee that he or she will remain in the program, because of its difficulty and the stu-dent’s possibly incomplete understand-ing of what the program requires or what she or he will face in undertaking it. Nationwide, the voluntary dropout rate for all doctoral students is 25% (Evelyn, 1999).

What does the future hold? Despite the recent economic slump, the demand for logistics undergraduate and master’s degrees should remain relatively strong (U.S. Department of Education, 2000; Graduate Manage-ment Admission Council, 2000). Logistics programs continue to search for new faculty members to staff both (a) existing traditional programs that continue to operate at capacity and (b) new logistics and supply-chain man-agement programs. This situation leads to an interesting problem in academia: Who will teach these students whom industry so strongly desires? Doctoral programs do not appear to have suffi-cient candidates in process to fill immediate demand. In response to this situation, a number of doctoral pro-grams have tried to gear up to meet this sudden demand but have discovered another problem: a lack of increase in the number of applicants to fill the doc-toral program openings.

TABLE 1. Business Doctoral Degrees Awarded

Marketing, management, School yeara Degrees awarded operations, and other subfields

1994–95 1,206 634

1995–96 1,216 663

1996–97 1,221 688

1997–98 1,165 618

1998–99 1,104 571

1999–2000 1,069 582

2000–01 1,049 556

aThis reflects the most recent information currently available.

TABLE 2. Logistics Hiring Statistics

Responding Assistant or open rank Reported number of Year universities positions available logistics PhD graduates

2000 17 16 at 13 universities 3 2001 18 17 at 13 universities 6 2002 20 19 at 17 universities 6 2003 20 18 at 13 universities 4

Method

Given that no single academic resource monitors the complete supply and demand process with regard to logistics and supply-chain management doctoral programs, we used both pri-mary and secondary data sources to assess supply and demand as well as factors affecting recruitment and enrollment. In February 2001, we sent one survey, which followed Dillman’s (2000) total design method, to the directors of the doctoral programs at the seven traditional programs as well as to the directors of 19 other programs that do not offer a logistics degree but support student research in this area. To obtain updated graduation and hiring numbers, we conducted a follow-up with the seven traditional programs in fall 2002. We asked respondents to pro-vide us with the following information:

• Number of doctoral students in the program and capacity of students that could be accommodated in the program. • Number of students graduating and seeking full-time academic positions.

• Departmental hiring plans for logistics faculty members over the fol-lowing 3 years.

To evaluate demand, we examined fac-ulty position announcements from three sources (the Chronicle of Higher Educa-tion, the American Marketing Associa-tion summer conference job search data-base, and the marketing listserv “elmar”) during summer 2001. The numbers and frequency of announcements represent demand within traditional marketing departments for PhD graduates with an emphasis in logistics or supply-chain management.

In 2001, we developed and sent two additional surveys (following the same research design) to gain insight into the numerous factors that may influence the PhD program evaluation and decision process and, thus, affect program enroll-ment. We selected 65 current logistics PhD students from the seven traditional programs (46% response rate) and both current and past MBA students (730) from three universities representing both public and private institutions from three different geographical areas (31% response rate). We designed the MBA

survey to obtain information from (a) MBA students currently considering a PhD program in marketing or logistics and (b) those who might consider enter-ing such a program at some point in the future.

Results

PhD Supply and Demand

In Table 3, we present the recent and anticipated near future supply of logis-tics PhDs. We provide graduation totals for the period 1998–2003. The figures given for the period of 2004–05 are based on numbers of students currently enrolled in logistics PhD programs and their projected graduation dates.

At the same time, demand for logis-tics PhDs has increased and ranges between 15 and 20 PhDs each year. Demand has increased progressively since the late 1990s. Although supply has increased, it has not kept pace with demand. This situation has been caused partly by logistics PhD programs’ inability to fill all available openings because of enrollment shortfalls.

We asked respondents to indicate which of the following factors might explain the differential between desired enrollment levels and actual enrollment in logistics PhD programs: (a) a decline in overall PhD program applications; (b) the strength of the job market and salary differential between industry and academic positions; and (c) doctoral program length. In the original survey, respondents from the seven traditional programs overwhelmingly stated that a decline in overall PhD program applica-tions was the main cause. This result suggests that these programs are faced with a smaller pool of candidates and presumably a smaller number of desir-able candidates. Three respondents cited salary differential as the

explana-tion, and none felt that doctoral program length was responsible for the shortfall. More interesting, even if desired capac-ity had been reached during this period, there would still be a shortage of candi-dates to fill the demand.

We should note that the near-future representation is a “best case” scenario. Although the enrollment of new stu-dents has increased slightly because of the current state of the economy, tradi-tional universities are still below capac-ity in the total number of students that they could enroll in their programs. In addition, we assume that all doctoral candidates currently will complete their degrees and pursue academic careers. However, this is unlikely because of the typical drop-out rate.

It is possible that the future supply represented in Table 3 will be augmented by doctoral students in related fields who are positioning themselves for logistics or supply-chain management openings. Specifically, there may be an influx of graduates from management and indus-trial engineering doctoral programs, which have had links to logistics and supply-chain management—although typically with an operations research per-spective. However, such departments may expand their course offerings in logistics and supply-chain management and need additional faculty members. Although we did not address this issue specifically in this study, the anecdotal evidence to date suggests that the crossover is extremely limited.

Prospective PhD Student Viewpoint

PhD students cited professional goals in academia (teaching and/or research) or a corporate career as reasons for their decision to pursue a PhD. Half of the respondents had personal goals (e.g., the challenge and ego fulfillment, the autonomy of the academic lifestyle) in

TABLE 3. Supply (Graduation Rates of Logistics PhDs)

1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

4 2 7 10 6 6 10a 11a

aEstimates are based on current enrollment and projected graduation dates.

addition to professional goals. Factors motivating MBAs to inquire about a PhD program include the need for intel-lectual stimulation, wanting to gain a sense of accomplishment, and changing careers to pursue an academic career. When asked to provide reasons for not considering a PhD program, an over-whelming majority of MBAs indicated they had not considered a career in academia. Other top reasons cited included the length of PhD programs, a lack of interest in the field of logistics, and financial commitments. In addition, some respondents did not perceive great monetary value associated with a PhD degree in the marketplace.

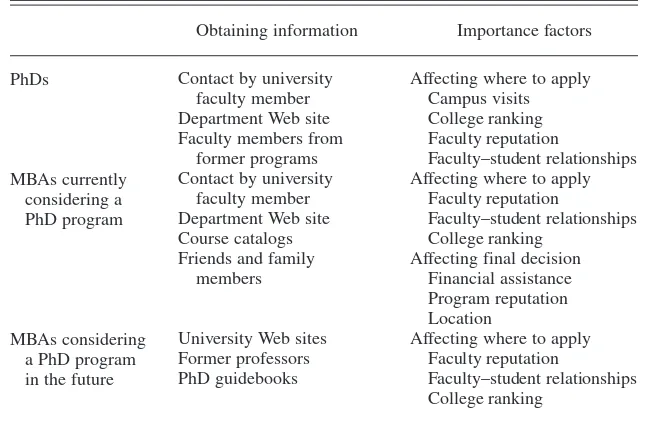

Once a student decides to pursue a PhD, he or she must evaluate alterna-tives and determine to which programs to apply, as well as which program to attend. To identify how prospective stu-dents obtain the information needed to evaluate logistics programs, we asked PhD and MBA students (those currently considering or who may consider a PhD program) to rank various methods. The results are summarized in Table 4.

Discussion

Our discussion begins with the fol-lowing question: Who will teach the future logistics and supply-chain stu-dents? In the short term, if the supply

pipeline cannot be filled, university pro-grams likely will be forced to use adjuncts, increase class sizes, increase teaching loads of existing faculty mem-bers, trim the number of times that elec-tive courses are offered in a given time period, and consider alternative delivery methods (e.g., courses on tape or alter-native media). Ultimately, the shortage of terminally qualified instructors can be remedied only through the produc-tion and hiring of more PhDs. There-fore, although supply currently is fixed and many new programs will compete for these graduates in the near future, one solution is to have existing PhD programs increase their enrollments in the logistics area.

To do this, one must acknowledge the disconnect between programs and prospective students, as indicated in our results. When asked why shortfalls occurred between actual and desired enrollment in logistics PhD programs, university respondents cited a drop-off in applications as the main reason. A few respondents indicated that salary differ-entials between industry and academic positions were responsible, and no one thought that program length was a factor. From the potential student perspec-tive (i.e., MBA respondents), most indi-cated that they were not interested in an academic career. Admittedly, there probably is little that doctoral programs

can do to attract these individuals except to educate MBA students and business managers on the benefits and rewards of the academic profession. The other top reasons cited for not considering a logis-tics program included the length of PhD programs and financial commitments. These concerns mirror similar reasons reported in education research. Given these responses, it is clear that there is a disconnect in programs addressing potential students’ concerns. In other words, the programs should practice what they preach by providing a unique value proposition and following through with good customer service once stu-dents are enrolled.

In all likelihood, program length and financial commitments are tied together tightly. If one anticipates spending 4 or 5 years pursuing a doctorate, one must forgo an industry salary for that length of time and yet support oneself—and possibly a family—during this period. This can be a daunting consideration, especially if a prospective student is not fully aware of the salaries currently being offered to PhD graduates in the logistics field. Our results indicate that a fair number of respondents do not realize that there are comparable salaries and benefits (e.g., indepen-dence, flexible work schedule, signifi-cant vacation opportunities, etc.) in the logistics academic marketplace.

Thus, it would appear that both the traditional and newer logistics doctoral programs must be more proactive and marketing focused in their efforts to meet their recruitment and enrollment objectives. Some scholars in the field of higher education have long advocated the importance of treating academic institutions like businesses that are responsive to meeting market demand and to achieving customer satisfaction (Liu, 1998).

Conclusion

Ultimately, to curb the stagnant trend in enrollment in existing PhD programs and to compete with savvy recruiting practices of the corporate marketplace, logistics and supply-chain doctoral pro-grams would be wise to adopt a market orientation. The starting point of a mar-ket orientation is marmar-ket intelligence.

TABLE 4. Information Related to Identification and Selection of PhD Programs

Obtaining information Importance factors

PhDs

MBAs currently considering a PhD program

MBAs considering a PhD program in the future

Contact by university faculty member Department Web site Faculty members from

former programs Contact by university

faculty member Department Web site Course catalogs Friends and family

members

University Web sites Former professors PhD guidebooks

Affecting where to apply Campus visits College ranking Faculty reputation

Faculty–student relationships Affecting where to apply

Faculty reputation

Faculty–student relationships College ranking

Affecting final decision Financial assistance Program reputation Location

Affecting where to apply Faculty reputation

Faculty–student relationships College ranking

Market intelligence includes information about customer needs and preferences as well as environmental factors that may affect business performance, such as technological innovations, competitor moves, and economic trends. Although the information provided in this study is a good beginning, intelligence genera-tion is not a one-time project. Rather, it involves designing a process that sys-tematically generates critical market intelligence. For recruiting practices, it is critical to build a system that not only identifies prospective students but also provides mechanisms for determining their individual needs and preferences. Moreover, logistics PhD programs face direct competition from logistics pro-grams at other universities as well as indirect competition from other business programs (e.g., operations management) and the corporate sector. Therefore, another important piece of market intel-ligence, competitor information, can be gained by benchmarking.

Market intelligence must be commu-nicated, disseminated, and perhaps even sold to people across the organization so that it can provide a shared basis for concerted action. This is particularly important for PhD recruiting processes in which multiple departments within the university (e.g., the graduate school, admissions, financial aid, or the college of business in addition to the logistics department) establish lines of commu-nication with prospective students. Coordination among these functions is essential for effective response to prospective student needs. The typical practice of assigning the responsibility for coordinating PhD recruiting to a fac-ulty member with little or no staff assis-tance further confounds this communi-cation problem.

The aim of generating and dissemi-nating market intelligence is to build a system that is responsive to the market-place. At the most elementary level, responsiveness in recruiting practices

requires anticipating the information needs of prospective students and pro-viding timely replies to requests for such information. Programs that adopt a mar-ket orientation should aim to be respon-sive not only in their communication processes but also in adjusting their pro-gram offerings to meet customer expec-tations. If the downturn in PhD applica-tions and the dropout rate from PhD programs are indications that the PhD program value propositions are weak, it may be time for new approaches. As in any value equation, the proposition can be made more attractive by either lower-ing costs (e.g., decreaslower-ing time or money spent) or raising benefits (e.g., increas-ing the student stipend).

Opportunities for Additional Research

Future research in this area is needed and should include an expansion of the samples used in this study. Our study investigated U.S. programs; much could be learned from examining international programs, which are very different in timing and structure from those in the United States. The supply–demand data could be more comprehensive. Perhaps logistics organizations or the AACSB could assist researchers in obtaining more complete information on these important issues.

Another way to strengthen the results obtained would be to supplement these data with information from qualitative interviews. We did not analyze the recruiting processes at various institu-tions directly. Interviews could be con-ducted with program coordinators, and recruiting materials could be collected for content analysis. More insight could be obtained through interviews with indi-viduals who evaluated PhD programs and/or who were recruited but chose not to enter a program. Researchers could survey recent doctoral graduates to deter-mine their perceptions on specific

improvements that are needed in the recruiting process. In addition to the sup-plemental information, an ongoing or longitudinal study of the issue of supply and demand of logistics scholars could be conducted. This issue will continue to affect the discipline; thus, we need to give it our ongoing attention to solve the problem of “Who will teach them?”

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to express appreciation to the reviewers of this manuscript for their insightful comments. We would also like to thank Donna F. Davis and Teresa M. McCarthy for their assis-tance in data collection for the study.

REFERENCES

American Assembly of Collegiate Schools of Busi-ness (AACSB). (1999). Demand for business PhDs continues slow rise, while doctoral

produc-tion falls steadily.Retrieved February 2001 from

http://www.aacsb.edu/Publications/Newsline Cooper, M. C. (2000).Logistics academic hiring

survey (working paper). Columbus: Ohio State

University, Department of Marketing. Cooper, M. C. (2001).Logistics academic hiring

survey (working paper). Columbus: Ohio State

University, Department of Marketing. Cooper, M. C. (2002). Logistics academic hiring

survey (working paper). Columbus: Ohio State

University, Department of Marketing. Cooper, M. C. (2003). Logistics academic hiring

survey (working paper). Columbus: Ohio State

University, Department of Marketing. Dillman, D. A. (2000). Mail and Internet surveys:

The tailored design method (2nd ed.). New

York: Wiley.

Evelyn, J. (1999). Corporate raiding. Black Issues

in Higher Education, 16(1), 30–33.

Fleming, J. (1998–99). Special research report: Selecting a graduate program in adult and con-tinuing education. Journal of Adult Education, 26(2), 2–13.

Graduate Management Admission Council. (2000). GMAT data.Retrieved February 2001 from http://www.gmac.com/research/data_ trends/gmat_data

Liu, S. S. (1998). Integrating strategic marketing on an institutional level. Journal of Marketing

for Higher Education, 8(4), 17–28.

National Opinion Research Center. (2001). Doc-torate recipients from United States universi-ties: Summary report 2001. Retrieved February 2001 from http://www.norc.uchicago.edu/ issues/docdata.htm

Petr, C. L., & Wendel, F. C. (1998). Factors influ-encing college choice by out-of-state students.

Journal of Student Financial Aid, 28(2), 29–40.

U.S. Department of Education. (2000, March). Fall enrollment in colleges and universities.

National Center for Education Statistics, 51.