Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 19:19

Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Anti-corruption reform in indonesia: an obituary?

Simon Butt

To cite this article: Simon Butt (2011) Anti-corruption reform in indonesia: an obituary?, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 47:3, 381-394, DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2011.619051 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2011.619051

Published online: 16 Nov 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 1773

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/11/030381-14 © 2011 Indonesia Project ANU DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2011.619051

ANTI-CORRUPTION REFORM IN INDONESIA:

AN OBITUARY?

Simon Butt

University of Sydney

Indonesia’s Anti-Corruption Court had until recently convicted all the defendants

brought before it by the Corruption Eradication Commission. Many of these were

well-known and politically powerful igures. Yet both the Court and the Commis -sion are under threat. Between February and October 2011, the Anti-Corruption

Courts issued more than 20 acquittals, and on 11 October 2011, for the irst time, a

defendant prosecuted by the KPK itself was acquitted. This article traces the history of the Court and the Commission and explains why their fall may be imminent. Both institutions have been the targets of efforts to discredit and hobble them,

ap-parently orchestrated by people the Commission has investigated. If the current

trend continues, the Anti-Corruption Court and the Corruption Eradication

Com-mission may soon join the growing list of Indonesia’s failed anti-corruption initia -tives.

Keywords: corruption, governance, rent seeking, bribery

INTRODUCTION

Before February 2011, Indonesia’s Anti-Corruption Court (Pengadilan Tindak Pidana Korupsi, or Tipikor Court) had convicted all 250 or so defendants that the Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, or KPK) had brought before it. The Tipikor Court had maintained this 100% conviction rate in cases involving high-proile and politically powerful igures, including parlia -mentarians, ministers, provincial governors and Bank Indonesia oficials – even Aulia Pohan, a member of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s extended fam-ily. Many judge the Court’s success by reference to this conviction rate. Yet suc-cess in this sense may be slipping from the grasp of the Tipikor Court and the KPK. In February 2011 the Jakarta Tipikor Court handed down its irst acquittal. By the beginning of October 2011, the Surabaya Tipikor Court alone had acquitted 21 defendants, and the Bandung Tipikor Court acquitted four defendants between August and October 2011.

In this article, I trace the rise of the KPK and the Tipikor Court and explain why their fall may be imminent. Both institutions have been the targets of well-orchestrated efforts to discredit and hobble them, launched by some of those the KPK has investigated. The Constitutional Court – probably inadvertently, as dis-cussed below – sowed the seeds for their weakening in 2006. More signiicant, however, have been events occurring since early 2009. In that year, some police,

382 Simon Butt

prosecutors and parliamentarians, themselves under threat of KPK investigation or connected with others who were, pushed back against the KPK and the Tipikor Court.

For their part, police and prosecutors sought to discredit and remove individual KPK commissioners. In this endeavour, they hold powerful trump cards: police can have KPK commissioners suspended simply by charging them; prosecutors can have them dismissed merely by bringing them to trial. In 2009, police charged the KPK chair with murder and two commissioners with misuse of power, trig-gering the suspension of all three. The chair was convicted following a highly questionable trial, but the commissioners were released after proving that they had been framed.

By contrast, parliamentarians sought to weaken the Tipikor Court and the KPK by legislatively removing some of the features responsible for their success. Per-haps the most signiicant of these features were the KPK’s ability to choose the cases it handles (thereby excluding ordinary police and prosecutors from those cases) and the Tipikor Court’s use of ad hoc (non-career) judges. Legislative efforts to weaken these and other features have borne fruit. In 2009, the national parliament passed Law 46/2009 on the Tipikor Court; I will show that the Court’s irst acquittal can be attributed directly to this Law. In 2011, parliamentarians pro -posed amendments to other statutes which, if passed, are likely to reduce the efi -cacy of the Tipikor Court and the KPK further, and may even remove the KPK’s power to prosecute.

THE INSTITUTIONAL DESIGN OF THE KPK AND THE TIPIKOR COURT

Law 30/2002, the statute that established the KPK, made it institutionally inde -pendent of government (art. 3). The Law authorises the KPK to investigate and prosecute most corruption cases itself and to take over corruption investigations and prosecutions from police and prosecutors in some circumstances (arts 8 and 9). It gives the KPK investigative powers that the police lack. These include pow -ers to wire-tap suspects’ phones without seeking court approval, to freeze bank accounts and to issue travel bans (art. 12). The Law also prohibits the KPK from dropping a case once it has progressed beyond initial investigations – a restric-tion aimed at preventing prosecurestric-tions from being dropped in return for bribes (Fenwick 2008). The KPK’s ive commissioners are selected through rigorous and transparent processes (arts 30 and 31) (Schütte 2011, in this issue). And, even though KPK investigators and prosecutors are secondments from the police force and the public prosecutor’s ofice, strong competition for positions and the use of private-sector recruitment services have ensured that, with some notable excep-tions, the integrity and professionalism of appointees have rarely been brought into question (Bolongaita 2010: 16–17).

A signiicant feature of the KPK’s institutional design has been its ability to exclude ordinary law enforcement institutions from handling particular corrup-tion cases, either by initiating an investigacorrup-tion itself, or by taking over a case that police or prosecutors have already begun investigating or prosecuting (Fenwick 2008; Bolongaita 2010: 16–17). This has been crucial to the anti-corruption effort, because Indonesia’s general law enforcement institutions are perceived to be largely ineffective in pursuing corruption allegations (Assegaf 2002).

One cause of their ineffectiveness is probably incompetence – in detecting cor-ruption, handling and preparing evidence and proving allegations at trial, for example. To be fair, convictions are notoriously dificult to obtain in corruption cases even in developed and well-resourced states. Evidence is often dificult to uncover, because perpetrators usually go to great lengths to prevent detection (Wagner and Jacobs 2008: 18; Pearson 2001: 39; ADB and OECD 2006: 17).

However, the primary reason for the ineffectiveness of general law enforce-ment institutions is likely to be that many, if not most, Indonesian law enforc -ers are themselves corrupt. Corruption is so endemic within the justice system that the system is often referred to as the ‘justice maia’ (maia peradilan). In most types of cases, including corruption cases, police can be ‘persuaded’ to drop an investigation, lose important evidence or charge a suspect with a lesser offence. In return for a bribe, prosecutors often drop a prosecution, present their case poorly at trial or seek a lenient penalty (Aspandi 2002: 33; Fenwick 2008: 406; Yunto 2008; Assegaf 2002: 130). The result is, in essence, immunity for those whose cases are handled by ordinary law enforcement institutions and who are willing and able to bribe their way out of trouble.

The Tipikor Court was established and located within the Central Jakarta Dis-trict Court with the sole function of hearing the cases that the KPK prosecutes (art. 53). Under the 2002 KPK Law, each case was to be presided over by a ive-judge panel, comprising two career ive-judges drawn from the general courts and three ’ad hoc judges’ (art. 58). These are legal experts – usually academics, legal practitioners and retired judges – employed to sit on Tipikor Court trials. Appeals were available to similarly constituted benches in the Jakarta High Court and the Supreme Court (arts 59–60).

The key to the Tipikor Court’s success has probably been this use of three ad hoc judges on each ive-judge panel. Although there are exceptions, Indonesian general court judges are not known for high levels of integrity and competence, and they have developed a reputation for acquitting or imposing short sentences in corruption cases (Butt 2009b). Indonesia’s most prominent anti-corruption non-government organisation, Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW), claims that general court career judges acquit in around 50% of corruption cases (Diansyah 2009). By contrast, ad hoc judges are considered more likely to be professional because they do not work within the existing judiciary and are therefore not tainted by its practices. Empanelling a majority of ad hoc judges appears to have been critical to the Tipikor Court’s maintenance of its 100% conviction rate. Some of its decisions have been split between the ad hoc and the career judges, with the majority ad hoc judges holding sway and convicting the defendant, and the minority career judges declaring that they would have acquitted or imposed a lower sentence (Fenwick 2008: 414).

The case of the Joint Investigating Team for Corruption Eradication (Tim Gabungan Pemberantasan Tindakan Korupsi, or TGPTK) brings into sharp relief the need to bypass ordinary law enforcers in corruption cases. The TGPTK was formed within the Attorney General’s Ofice in 2000 to help with dificult-to-prove corruption cases. Like many pre-KPK anti-corruption initiatives, the TGPTK had limited powers (Assegaf 2002; Hamzah 1984). It could only coordinate investiga -tions and prosecu-tions that ordinary police and prosecutors conducted. Its inabil -ity to investigate or prosecute on its own initiative was seen as its main weakness

384 Simon Butt

(Assegaf 2002). The TGPTK oversaw the completion of only around 10% of the cases submitted to it (Assegaf 2002: 135), leading its head, former Supreme Court judge and respected reformist Adi Andojo Soetjipto, to resign in frustration in 2001 (Jakarta Post, 28/3/2001).

While the TGPTK was only ever intended to remain until the KPK was estab -lished, it did not last even as long as that. When in 2001 it began investigating allegations that Supreme Court judges had received bribes to ix cases, the judges responded by challenging, in the Central Jakarta District Court, the jurisdiction of the TGPTK to investigate them. They were successful, albeit on highly dubious legal grounds, and the investigation into them was declared invalid. The judges also sought, before the Supreme Court, a judicial review of the government regula-tion that established the TGPTK. Again they were successful despite quesregula-tionable legal arguments (Butt and Lindsey forthcoming). The Supreme Court invalidated the regulation, thereby disbanding the TGPTK. The judges were therefore able to escape scrutiny completely, by appealing to their inferiors in the District Court and their brethren on the Supreme Court. This case is still often cited to explain why law enforcement institutions cannot be trusted to handle corruption cases and, in particular, how they have ‘guarded their own’ in the face of corruption allegations (Butt and Lindsey forthcoming).

THE KPK UNDER CHAIR TAUFIQURRAHMAN RUKI (2004–08)

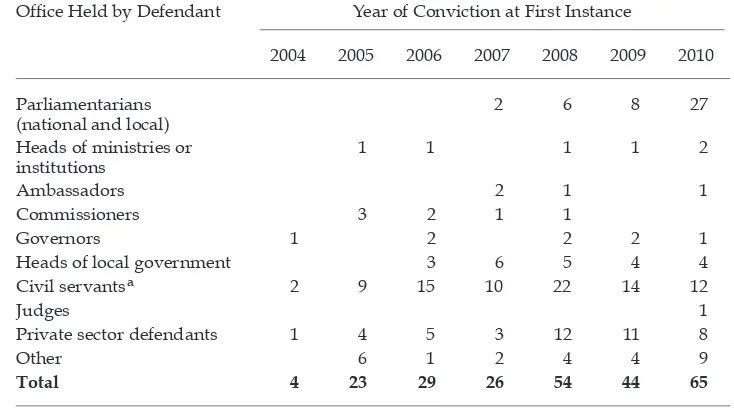

From its irst prosecution in 2004 until the end of 2007, under the leadership of Tauiqurrahman Ruki, the KPK for the most part pursued mid-level national ofi -cials and mid-level to senior regional government ofi-cials, securing over 80 con -victions in the Tipikor Court (table 1).

However, not all observers heralded the success of the KPK – Tipikor Court ‘team’. Some lawyers complained that the Tipikor Court must have ignored the presumption of innocence to have maintained its conviction rate, and that its 20 judges lacked the judicial skills needed to preside over trials and write deci-sions (Hukumonline 2009; Syamsuddin 2007). Others pointed out that the over-all impact of the KPK and the Tipikor Court was low: the KPK prosecutes and the Tipikor Court decides less than 5% of corruption cases Indonesia-wide (Butt 2011: 47). Yet perhaps the most sustained criticism – commonly levelled by anti-corruption activists and the media – was about the KPK’s case selection. The crit-icism was that the KPK chose only ‘easy’ cases, avoiding the ‘big ish’ – including former President Soeharto, his family and inner circle, senior military personnel and those involved in the bank liquidity scandals in the aftermath of the 1997 inancial crisis (Butt 2009b).

While on a general level this criticism has some merit, it neglects the fact that the KPK was a new institution operating in a hostile political environment and still inding its place. It also overlooks several important convictions, including those of former national ministers and parliamentarians and the most senior of local government oficials. Most importantly, by keeping clear of the ‘big ish’ – those with strong ‘live’ political connections – the KPK avoided the powerful resistance that these people could muster and, potentially, a fate similar to that of the TGPTK. Starting with smaller cases allowed the KPK to build momentum, experience, expertise and public support before tackling the cases the critics highlighted.

Ofice Held by Defendant Year of Conviction at First Instance

2006

Including public prosecutors and police.

During this period, some of those the KPK had prosecuted and the Tipikor Court had convicted attempted to ‘push back’ against both institutions. Resis-tance was, however, limited largely to challenges, lodged with Indonesia’s Constitutional Court, to the constitutionality of aspects of the KPK Law and Indonesia’s 1999 Anti-Corruption Law (amended in 2001). Though some of these challenges were successful, they did not signiicantly affect the way the KPK and the Tipikor Court worked or hinder their performance (Butt 2009a), with one critical exception.

In a 2006 case, the Constitutional Court decided that the Tipikor Court was itself unconstitutional because its establishment had created a dual system. Indo -nesia’s general courts continued to hear the cases that the KPK decided not to prosecute, and this, the Court found, breached the constitutional right to equality before the law.1 Implicit in the Constitutional Court’s reasoning was that convic

-tion rates were higher in the Tipikor Court than in the general courts, to the disad-vantage of defendants the KPK chose to pursue (Butt 2009a). The Constitutional Court gave the national parliament three years to pass a new statute that gave the Tipikor Court exclusive jurisdiction over corruption cases. Parliament met this deadline, but with a statute that, in ways explained below, signiicantly weakens the KPK and the Tipikor Court.

1 Constitutional Court Decision No. 012-016-019/PUU-IV/2006.

(Assegaf 2002). The TGPTK oversaw the completion of only around 10% of the cases submitted to it (Assegaf 2002: 135), leading its head, former Supreme Court

, 28/3/2001).

While the TGPTK was only ever intended to remain until the KPK was estab

allegations that Supreme Court judges had received bribes to ix cases, the judges

of the TGPTK to investigate them. They were successful, albeit on highly dubious

tion that established the TGPTK. Again they were successful despite questionable

the regulation, thereby disbanding the TGPTK. The judges were therefore able to

THE KPK UNDER CHAIR TAUFIQURRAHMAN RUKI (2004–08)

From its irst prosecution in 2004 until the end of 2007, under the leadership of Tauiqurrahman Ruki, the KPK for the most part pursued mid-level national ofi cials and mid-level to senior regional government oficials, securing over 80 con

the KPK and the Tipikor Court was low: the KPK prosecutes and the Tipikor Court decides less than 5% of corruption cases Indonesia-wide 2011: 47)

icism was that the KPK chose only ‘easy’ cases, avoiding the ‘big ish’ – including

inancial crisis (Butt 2009b).

inding its place. It also overlooks several important convictions, including those

government oficials. Most importantly, by keeping clear of the ‘big ish’ – those

that these people could muster and, potentially, a fate similar to that of the TGPTK.

TABLE 1 Corruption Convictions by Defendant Category, 2004–10

Ofice Held by Defendant Year of Conviction at First Instance

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Parliamentarians

Private sector defendants 1 4 5 3 12 11 8

Other 6 1 2 4 4 9

Total 4 23 29 26 54 44 65

a Including public prosecutors and police.

Source: KPK (2011).

386 Simon Butt

THE KPK UNDER ANTASARI AZHAR (2008–09)

Under the leadership of Antasari Azhar (2008–09), the KPK began targeting some of the ‘big ish’ that it had previously avoided in the parliament, public prosecution and the police force (table 1). This, it seems, drew more intense retaliation – this time from or through police and prosecutors. In 2009, the KPK had been investigating senior law enforcement oficials. Perhaps the most promi -nent was Susno Duadji, a former chief of criminal investigations with the national police. The KPK investigated him for planning, in return for a bribe, to help a depositor retrieve funds illegally from the ailing Bank Century – a bank that the national government had bailed out in November 2008 to the tune of Rp 6.7 tril -lion (approximately $524 mil-lion) (Jansen 2010).

Though pursuing corruption cases involving law enforcement institutions is clearly within the KPK’s mandate, targeting police and prosecutors invites dan-ger for KPK commissioners. Under the KPK Law, the president must suspend any KPK commissioner formally charged with a crime (art. 32(1)), and remove the commissioner once he or she is prosecuted (art. 32(2)) – regardless, it seems, of whether the commissioner is in fact tried or convicted. Though apparently designed to safeguard the KPK’s reputation, these provisions give police and prosecutors tremendous leverage over the KPK. Police and prosecutor decisions to charge and prosecute are unilateral and largely unreviewable.

THE FRAMING OF BIBIT AND CHANDRA – ANTASARI TOO?

Police and prosecutors used these powers from early March 2009 against the KPK chair, Antasari Azhar, who was arrested in March 2009, and from mid-2009 against two other KPK commissioners, Chandra Muhammad Hamzah and Bibit Samad Rianto.

Police arrested Antasari for ordering the murder of Nasruddin Zulkarnaen, the husband of a woman with whom Antasari allegedly had a sexual encounter. Nas-ruddin was shot while travelling home in his car. Police and prosecutors alleged that Nasruddin had attempted to blackmail Antasari, threatening to reveal the encounter to the media unless Antasari helped him obtain business opportunities and a promotion.

Meanwhile, in September 2009 police arrested Bibit and Chandra for abusing their powers to issue and revoke travel bans. The only evidence they could pro-duce to substantiate the charges was a travel ban document that was later proven to be a fake. Yet because police had formally charged Bibit and Chandra, the presi-dent still suspended both commissioners under art. 32(1) of the KPK Law. Bibit and Chandra knew that they would be dismissed under art. 32(2) once a prosecu-tion commenced. In an attempt to prevent this, they challenged art. 32(2) in the Constitutional Court, arguing that it contravened their constitutional right to the presumption of innocence.

The Court’s proceedings were broadcast live on television and streamed online. During the irst hearing of the case, the Constitutional Court allowed the KPK to play wire-tapped phone conversations between suspects the KPK was investigat-ing and senior law enforcement oficials. The recordinvestigat-ings clearly revealed a plot to frame Bibit and Chandra. Voices identiied on the tape included the then Deputy Attorney General, Abdul Hakim Ritonga; the former Head of Intelligence at the

Attorney General’s Ofice, Wisnu Subroto; and Susno Duadji. The Court unan -imously declared that Bibit and Chandra had been framed and should imme-diately be released and re-instated.2 The ‘Team of 8’ – a fact-inding team that

President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono had himself established to investigate the case – drew similar conclusions. Soon afterwards, prosecutors issued an oficial Declaration of Cessation of Prosecution (SKPP) for both Bibit and Chandra. Susno and Ritonga were forced to resign (Dhyatmika et al. 2009; Haryadi 2009).

Antasari Azhar’s trial began on 8 October 2009 in the South Jakarta District Court. The Court accepted the chain of events put forward by the prosecution, to which Sigid Haryo Wibisono, a businessman and the chair of the Merdeka daily newspaper, testiied. Sigid attested that Antasari met with him and Williardi Wizar, a former South Jakarta police chief, and asked them to help him ‘pacify’ (mengamankan) threats Nasruddin had made against him. Sigid also testiied that

Wizar had then contacted others to arrange and perform the killing. The Court also accepted evidence from Sigid that Antasari had promised to repay the ‘opera-tional funds’ for the murder that Sigid initally provided. In early 2010, Antasari was convicted and sentenced to 18 years in prison.3

Antasari’s trial was highly questionable: no credible evidence was adduced pointing to his guilt (Butt 2011: ch. 5). Most problematic was the testimony of the prosecution’s own forensic and ballistic expert, Abdul Munim Idris. He testiied that the gun the prosecution had produced as the murder weapon could not ire the bullets found in the victim and that it was in such poor condition that it could not have been used in the murder. Idris’s testimony was not challenged at trial, yet the Court simply ignored it. However, the authenticity of the murder weapon was surely central to the prosecution’s case, as it is in most murder trials. It thus seems inconceivable that an objective panel of judges could have found Antasari guilty ‘legally and convincingly’ – the Indonesian equivalent of ‘beyond reason -able doubt’ (Butt 2011: ch. 5). The trial smacks of a set-up to remove Antasari, under whom the KPK had become signiicantly bolder. Antasari’s appeal to the Jakarta High Court was unsuccessful.

Despite the exposure of Bibit and Chandra’s framing, the widespread public perception that politically strong igures had the KPK in their sights, and the paucity of evidence adduced at trial to support his conviction, Antasari enjoyed little public support. Very few openly expressed the view that he, too, might have been framed. Some anti-corruption reformists I interviewed in Jakarta voiced doubts about his integrity: allegations of corruption surrounded both his appointment as KPK chair and cases he had handled in previous prosecutorial posts (Handayani, Kustiani and Nilawaty 2009) (though there is much to coun-teract these doubts, not least the KPK’s greater focus on corruption by ‘big-ger ish’ under his leadership). These unproven allegations against Antasari appeared to morph into perceptions that he might have been capable of order-ing Nasruddin’s murder. Whatever one’s view of Antasari’s integrity or even his capacity for murder, his trial was clearly unfair. Reformists should have pro-tested more vocally against his conviction based on such a lawed prosecution case.

2 Constitutional Court Decision No. 133/PUU-VII/2009.

3 Decision No. 1532/PIDB/2009/PN.JKT.SEL.

388 Simon Butt

Nevertheless, the tide of public support might yet turn in Antasari’s favour. He appealed to the Supreme Court in July 2010. By late September 2010, a two-judge majority had upheld his conviction and sentence.4 Ignoring the prob

-lematic ballistic evidence mentioned above, the majority held that the lower courts had in fact considered all relevant evidence and had not misapplied the law. However, Professor Dr Surya Jaya issued a dissenting judgment.5 A former

Hasanuddin University law academic, Judge Surya Jaya was appointed to the Supreme Court as a non-career judge in April 2010 after serving as an ad hoc Tipikor Court appeals judge. He is reportedly the youngest judge ever appointed to the Supreme Court (Fajar Online, 3/4/2010).

Judge Surya Jaya held that the lower courts had breached Indonesia’s Code of Criminal Procedure (Kitab Undang-undang Hukum Acara Pidana, or Kuhap) by ignoring what he described as ‘determinative’ expert evidence. According to Judge Surya Jaya, Idris’s testimony raised doubts about whether the ‘assas -sins’ who had already been convicted had in fact been involved in the shooting and, in turn, whether Antasari had ordered it. If the lower courts had considered this testimony, he continued, they might well have reached a different decision. Judge Surya Jaya also accepted that, though Antasari might have met with friends to complain about being threatened and to seek protection and help, there was no evidence that he had discussed murdering Nasruddin, let alone planned or promised to inance the murder. Judge Surya Jaya concluded that he would have acquitted Antasari.

Judge Surya Jaya might also have commented on another signiicant law in the decisions of the majority and the lower courts. A fundamental rule of Indonesian evidence law is that ‘one witness equals none’ (unus testis nullus testis) (Handayani and Aprianto 2009). In other words, witness testimony without corroboration at trial, from another witness or other evidence, is insuficient to ground a convic -tion (Kuhap, art. 185). It seems that the majority in the Supreme Court, and the judges in the lower courts, breached this principle in convicting Antasari. By the time Antasari’s case came to trial, only Sigid remained willing to testify against him. All others that had been convicted for their alleged involvement in the plot to kill Nasruddin – including several alleged intermediaries and assassins – had retracted their police statements implicating Antasari. Many of them claimed that they had been coerced into making those statements.

In early February 2011, the National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM) announced that it would investigate the fairness of Antasari’s trial. The probe was launched in response to claims – made by Gayus Tambunan, infa -mously convicted of corruption within the Indonesian tax ofice – that Cirus Sinaga, who led both his and Antasari’s prosecution, was involved in a plot to sideline Antasari (Parlina 2011).6 Indonesia’s Judicial Commission (Komisi Yudisial) also investigated allegations that the judges who decided his case breached the judicial code of ethics by ignoring ballistic, forensic and other evidence (Aprianto and Cipta 2011). At time of writing the Judicial Commission

4 Supreme Court Decision No. 1429 K/Pid/2010.

5 The following description draws from pp. 58–61 of Judge Surya Jaya’s judgment.

6 ‘Komnas to probe Antasari trial process’, Jakarta Post, 31/1/2011.

had completed its investigation and recommended to the Supreme Court that it discipline the district court judges who had presided over Antasari’s trial. The Commission concluded that the judges had indeed breached the Judicial Code of Ethics and Behaviour Guidelines by ignoring the expert ballistic evidence, and recommended their removal from adjudicative duties for six months. The Supreme Court, which has the inal say on whether to impose most types of pun -ishments upon judges, rejected the recommendation in early September 2011, on the basis that the Judicial Commission lacked power to assess the technical–legal correctness of judicial decisions (Hukumonline 2011d). (This ground is commonly employed by the Supreme Court to avoid Commission scrutiny of its own judges and judges under its control in the lower courts (Colbran 2009)). Antasari had asked the Supreme Court to exercise its peninjauan kembali (‘review’) jurisdiction, under which it could re-open his case and reconsider its decision. As this article went to press, the Court had not yet rendered a decision.

STATUTORY REFORM: CRIPPLING THE KPK AND THE TIPIKOR COURT?

By November 2009, the national parliament had passed Law 46/2009 on the Anti-Corruption Court in response to the 2006Constitutional Court decision discussed above. This statute addressed the Constitutional Court’s concerns about ‘dualism’ – the hearing of corruption cases by two types of courts with different conviction rates, resulting in possible violation of the principle of equality before the law – by giving the Tipikor Court exclusive jurisdiction over all corruption cases. But the statute also made signiicant institutional changes to the Tipikor Court, and implicitly to the KPK, that jeopardise future corruption convictions. Law 46/2009 required that by 29 October 2011 Tipikor courts be established in district courts in Indonesia’s 33 provincial capitals (art. 35), a task the Supreme Court completed within the deadline (Hukumonline 2011f).

At irst blush, expanding the Tipikor Court might seem like a boost for the Court and for the anti-corruption movement. Yet it seems highly unlikely – per-haps impossible – that the success of the Jakarta Tipikor Court will be replicated in these regional courts. Law 46/2009 gives the chair of the district court in which the Tipikor Court is housed – a career judge – power to determine whether ad hoc judges will make up the majority on each Tipikor court panel. Given that the Supreme Court is having trouble inding enough ad hoc judges to ill these new courts, they will probably constitute the minority in most cases. This appears to have already begun happening in the Semarang, Surabaya and Bandung Tipikor Courts (Hidayat et al. 2011). In these courts, it appears that three career judges and two ad hoc judges preside over cases involving more than Rp 100 billion, and that two career judges and one ad hoc judge decide cases involving less than Rp 100 billion. Career-judge majorities are likely to win the day in split decisions. The likely result is fewer convictions.

Law 46/2009 could carry even more dire consequences for the KPK. The Law does not once mention the KPK. It mentions only general public prosecu -tors (penuntut umum) being able to prosecute before the Tipikor Court. This has two important consequences. First, ordinary public prosecutors can now bring claims before Tipikor courts – and have already done so. Given the widespread corruption and incompetence within Indonesia’s prosecution service, the Tipikor

390 Simon Butt

courts will probably not be able to maintain a high conviction rate. They will be more likely to ind fault with the evidence and arguments put by ordinary pros -ecutors than the Jakarta Tipikor Court has done for the pros-ecutors of the KPK. Indeed, prosecutorial incompetence seems to have resulted in the Tipikor Court’s irst acquittal, to which I turn below. Add to this the potential for majority career-judge panels in regional Tipikor courts, and the result is that almost all corruption cases will be controlled by ordinary prosecutors and judges – the very people whose inluence the KPK and the Tipikor Court were established to circumvent.

Second, and perhaps more signiicantly, the KPK’s omission from Law 46/2009 leaves its prosecutorial function tenuous. According to press reports, this omis-sion was not a drafting oversight (Handayani et al. 2009; Wright 2009; Kustiani et al. 2009). Some parliamentarians – perhaps even a majority – had wanted to excise the KPK’s prosecutorial powers but, in a compromise, the KPK’s role was left ambiguous in Law 46/2009.

At the time of writing, the KPK continues to prosecute in the Tipikor courts. Yet it is highly likely that defendants will seek to exploit this ambiguity and argue that Law 46/2009 has, in fact, removed the KPK’s jurisdiction to prosecute, along the lines of the Supreme Court judges’ challenge to the jurisdiction of the TGPTK, discussed above. There are certainly reasonable legal arguments against including the KPK’s prosecutors within the deinition of penuntut umum (Butt 2011: 120). If the KPK were to lose a challenge to its jurisdiction to prosecute, its prosecutorial powers might be stripped away, leaving it as a mere investigative institution. If this occurred, then ordinary prosecutors would regain complete control over corruption cases.

More recently, politicians have pushed for revisions to the 2002 KPK Law and the 1999 Anti-Corruption Law (amended in 2001). These statutes are critical to the effective functioning of the KPK and the Tipikor Court. The KPK Law is the statutory source for the KPK’s power to perform investigations, prosecutions, wire-taps and the like. The Anti-Corruption Law deines and sets punishments for various types of corruption, and arguably makes corruption easier to pursue than most other types of crimes (Butt 2009b).

Proposed amendments to the 1999 Anti-Corruption Law, in circulation from early 2011, explicitly remove the KPK’s prosecutorial function and reduce the penalties for some corruption offences (Hukumonline 2011a). Fortunately, a public backlash against the revisions, driven by the KPK and ICW, has led to the with -drawal of the amendments from parliamentary consideration to allow more pub-lic comment.

Amendments to the KPK Law have not yet been drafted. However, ICW obtained the ‘terms of reference’ for the revisions and claims that they seek to interfere with the KPK’s wire-tapping powers; to allow the KPK formally to cease investigations (leaving open the possibility of this occurring in response to bribery); and to increase the KPK’s role in corruption prevention, which would presumably divert its attention from enforcement (Hukumonline 2011b). Amend-ing the KPK Law reportedly sits at number four on the 2011 National Legislative Program, a list of priority legislation that parliament should aim to enact within the year (Hukumonline 2011a).

It is hardly surprising that Law 46/2009 and the proposed KPK and Anti-Corruption Law revisions seek to enfeeble the KPK. In the months before Law

46/2009’s enactment, the KPK had been investigating parliamentarians for cor -ruption and had conducted very public raids on their ofices. In particular, it had investigated allegations that 30 parliamentarians had each received travel-ler’s cheques worth Rp 500 million to elect Miranda Goeltom as Bank Indonesia’s deputy governor in 2004 (Hidayat and Febriyan 2011). By June 2009, the KPK had formally charged four of them and by July it had publicly identiied 26 more serving and former legislators as recipients of the cheques. The KPK has also investigated parliamentarians for involvement in other corruption cases. In 2011, ICW estimated that, once the KPK had completed its current investigations into parliamentarians, more than 100 might be ensnared (Hukumonline 2011c). Many parliamentarians and the political parties to which they belong had, and still have, much to gain from a weakened KPK and Tipikor Court.

THE TIPIKOR COURT’S FIRST ACQUITTAL: A GLIMPSE OF THE FUTURE

In late February 2011, the Central Jakarta Tipikor Court issued the irst acquittal in its seven-year history. The defendant was Mieke Henriett Bambang, secretary to Bank Indonesia Governor Burhanudin Abdullah from 2003 to 2008. She was accused of impeding a KPK investigation into Abdullah.7 After searching

Burha-nudin’s ofice, the KPK had sealed off a cupboard in a computer desk (Hukumonline

2011a). Mieke had allegedly removed the seal and, the KPK claimed, had taken some of the documents and given them to another Bank Indonesia employee. Mieke denied any wrong-doing, claiming that she was following instructions to put the documents in order (merapikan) and that she had not removed any mate-rial (Silalahi 2011).

The case was the irst brought before a Tipikor court by a public prosecutor. According to the account of the case provided by Indonesia’s leading legal news service, Hukumonline (2011c), the public prosecution’s performance was far below the standard for which the KPK has become well known. The KPK usually sends at least two prosecutors to the cases it prosecutes, and its indictments usually run to hundreds of pages (Hukumonline 2011a). By contrast, in this case, the indictment against the defendant was presented by only one prosecutor and was a mere ive pages long.

The indictment was also legally lawed, the Tipikor Court decided. Article 142(3) of the Kuhap requires that indictments must be accurate, clear and com-plete. The indictment in this case appeared to fulil none of these requirements; it did not clearly set out the crime the prosecution alleged the defendant had com-mitted (Hukumonline 2011b). (Mieke’s lawyer even claimed that the indictment had been largely copied and pasted from the summary of evidence that police had submitted to prosecutors, and did not include the evidence of the ive KPK oficers who had reported Mieke for impeding their work (Silalahi 2011)). This left the Tipikor Court with little choice but to dismiss the case before witnesses were called – a rare event in Indonesia (Hukumonline 2011b).

This case raises signiicant questions about prosecutorial competence and resource allocation, particularly in corruption cases. It also casts doubt upon the

7 For a discussion of the Abdullah case, see Kong and Ramayandi (2008).

392 Simon Butt

public prosecution’s case selection criteria. Of all of its ongoing corruption cases, this was hardly an appropriate one to choose as its irst to bring before the Tipikor Court. The defendant had not even been accused of committing corruption her-self. All in all, this case does not bode well for non-KPK prosecutions in Indo -nesia’s Tipikor courts.

CONCLUSION

Mieke’s acquittal is likely to be the irst of many. In August and September 2011 alone, the Bandung Tipikor Court acquitted three defendants in trials tainted by allegations of judicial impropriety, including the bribing of judges and ques-tionable judicial reasoning. The Surabaya Tipikor Court had acquitted dozens of defendants by the end of September 2011 (Anton 2011). These acquittals were cases brought by ordinary public prosecutors.

Of particular signiicance is that on 11 October 2011, for the irst time, a defend -ant whom the KPK had prosecuted was acquitted. This was deeply embarrass-ing for the KPK, which had been able to deny responsibility for previous Tipikor court acquittals by pointing out that ordinary public prosecutors – not the KPK – had prosecuted them. The defendant was Mochtar Mohammad, the former mayor of Bekasi, whom the KPK had prosecuted for corruption associated with the regional budget. According to a Hukumonline report on the case (Hukumonline

2011e), the Bandung Tipikor Court found insuficient evidence to substantiate the charges made against the defendant. Hukumonline also reported that, before read-ing out its reasons for the acquittal, the panel of judges declared that ‘the courts are an independent pillar of democracy and are free of pressure from anyone, including trial by the press. The courts are, in fact, not only institutions that pun-ish, but ... also institutions that provide justice’. If this statement is taken as an indication of future intent, the Bandung Tipikor Court might be expected to issue many more acquittals.

Even though attempts at discrediting Bibit and Chandra back-ired, and impro -priety in Antasari’s trial might still be revealed, the institutional features of the Tipikor Court and the KPK that set them apart from ordinary police, prosecu-tors and courts are being chipped away. Ordinary police, prosecuprosecu-tors and judges appear poised to regain the exclusive control over corruption cases that they lost to the KPK and the Tipikor Court under the 2002 KPK Law. If the current trajec -tory continues, within a few short years the Tipikor Court and the KPK will join the growing list of Indonesia’s failed anti-corruption initiatives.

REFERENCES

ADB and OECD (Asian Development Bank and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2006) Anti-corruption Policies in Asia and the Paciic: Progress in Legal and Institutional Reform in 25 Countries, Asian Development Bank, Manila.

Anton, A. (2011) ‘Red report card for Corruption Court’, Tempo, 5 October. Aprianto, Anton and Cipta, Ayu (2011) ‘Antasari’s quest’, Tempo, 27 May.

Aspandi, Ali (2002) Menggugat Sistem Hukum Peradilan Indonesia Yang Penuh Ketidakpastian

[Challenging an Indonesian Judicial System that is Full of Uncertainty], Lembaga Kajian Strategis Hukum Indonesia (Institute for Strategic Study of Indonesian Law)

and Lutfansah Mediatama, Surabaya.

Assegaf, Ibrahim (2002) ‘Legends of the fall: an institutional analysis of Indonesian law

enforcement agencies combating corruption’, in Corruption in Asia: Rethinking the Gov-ernance Paradigm, eds Timothy Lindsey and H.W. Dick, Federation Press, Sydney.

Bolongaita, Emil P. (2010) ‘An exception to the rule? Why Indonesia’s Anti-Corruption

Commission succeeds where others don’t – a comparison with the Philippines

Ombuds-man’, Anti-corruption Resource Centre, Bergen (Norway), available at <http://www. u4.no/document/publication.cfm?3765=an-exception-to-the-rule>.

Butt, Simon (2009a) ‘”Unlawfulness” and corruption under Indonesian law’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 45 (2): 179–98.

Butt, Simon (2009b) ‘Indonesia’s anti-corruption drive and the Constitutional Court’, Com-parative Law Journal 4 (2): 186–204.

Butt, Simon (2011) Corruption and Law in Indonesia, Routledge Contemporary Southeast Asia Series, Routledge, London.

Butt, Simon and Lindsey, Timothy (forthcoming) ‘Uninished business: law reform, gov

-ernance and the courts in post-Soeharto Indonesia’, in Indonesia, Islam and Democratic Consolidation, eds Mirjam Kunkler and Alfred Stepan, Columbia University Press.

Colbran, N. (2009) ‘Courage under ire: the irst ive years of the Indonesian Judicial Com -mission’, Australian Journal of Asian Law 11 (2): 273–301.

Dhyatmika, Wahyu, Hadad, Toriq, Damayanti, Ninin, Tauiq, Rohman and Tauik, M.

(2009) ‘How to cage a house lizard’, Tempo, 16 November.

Diansyah, F. (2009) Weakening of Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) in Indonesia: Inde-pendent Report, Indonesia Corruption Watch and National Coalition of Indonesia for Anticorruption, Doha, November.

Fenwick, Stewart (2008) ‘Measuring up? Indonesia’s Anti-Corruption Commission and the

new corruption agenda’, in Indonesia: Law and Society, ed. Timothy Lindsey, 2nd edition, Federation Press, Sydney.

Hamzah, Andi (1984) Korupsi di Indonesia: Masalah dan Pemecahannya [Corruption in Indo

-nesia: Problems and Solutions], Gramedia, Jakarta.

Handayani, Anne L. and Aprianto, Anton (2009) ‘When one equals none’, Tempo, 26 Octo -ber.

Handayani, Anne L., Aprianto, Anton, Muhtarom, Iqbal and Wibowo, Eko Ari (2009) ‘Pull -ing the tiger’s teeth’, Tempo, 28 September.

Handayani, Anne L., Kustiani, Rini and Nilawaty, Cheta (2009) ‘Tragedy of the dapper prosecutor’, Tempo, 11 May.

Haryadi, Rohmat (2009) Chandra–Bibit: Membongkar Perseteruan KPK, Polri, dan Kejaksaan

[Chandra–Bibit: Breaking Down Hostilities between the KPK, the Police, and the Pros

-ecution], Mizan Media Utama, Jakarta.

Hidayat, Bagja and Febriyan (2011) ‘Go to jail ... directly to jail’, Tempo, 15 February. Hukumonline (2009) ‘DPR dan (anti) korupsi “sehidup semati”: catatan awal tahun 2009

[The DPR and (anti) corruption as bedfellows: comments in early 2009]’, 5 January.

Hukumonline (2011a) ‘Pertama kali kasus kejaksaan disidang di Pengadilan Tipikor Jakarta

[The irst public prosecution case heard in the Jakarta Tipikor Court]’, 31 January.

Hukumonline (2011b) ‘Pengadilan Tipikor Jakarta bebaskan seorang terdakwa [Jakarta Tipikor Court frees defendant]’, 21 February.

Hukumonline (2011c) ‘Busyro: UU KPK tak perlu direvisi [Busyro: no need to revise KPK Law]’, 3 March.

Hukumonline (2011d) ‘KY–MA kordinasi untuk kasus Antasari [The Judicial Commission and Supreme Court will coordinate on the Antasari case], 15 September.

Hukumonline (2011e) ‘Majelis menilai pasal di UU Pemberantasan Tipikor tidak jelas [Panel considers articles in the Corruption Eradication Law to be unclear]’, 11 October. Hukumonline (2011f) ‘Jumlah Pengadilan Tipikor lengkap 33 [Number of Tipikor Courts

complete at 33]’, 22 October.

394 Simon Butt

Jansen, David (2010) ‘Snatching victory’, Inside Indonesia 100, available at <http://www.

insideindonesia.org/stories/snatching-victory>.

Kong, Tao and Ramayandi, Arief (2008) ‘Survey of recent developments’, Bulletin of Indo-nesian Economic Studies 44 (1): 7–32.

KPK (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, Corruption Eradication Commission) (2011) Laporan Tahunan Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi 2010 [KPK Annual Report 2010], KPK, Jakarta.

Kustiani, Rini, Aprianto, A., Wibowo, Eko Ari and Sutarto (2009) ‘A “middle of the road”

policy’, Tempo, 12 October.

Parlina, Ina (2011) ‘Judicial Commission says Antasari trial ishy’, Jakarta Post, 13 April. Pearson, Zoe (2001) ‘An international human rights approach to corruption’, in Corruption

and Anti-corruption, eds Peter Larmour and Nick Wolanin, Asia Paciic Press, Canberra.

Schütte, Soie Arjon (2011) ‘Appointing top public oficials in a democratic Indonesia: the

Corruption Eradication Commission’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 47 (3): 355– 79, in this issue.

Silalahi, Mustafa (2011) ‘Pengadilan Tindak Pidana Korupsi: sederhana membawa bebas [Tipikor Court: mediocrity brings acquittal]’, Tempo, 7 March.

Syamsuddin, A. (2007) ‘Benarkah KPK tidak pernah bersalah? [Is it true that the KPK is never wrong?]’, Kompas, 27 February.

Wagner, Benjamin B. and Jacobs, Leslie Gielow (2008) ‘Retooling law enforcement to inves

-tigate and prosecute entrenched corruption: key criminal procedure reforms for Indo -nesia and other nations’, University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Economic Law

30 (1): 183–266.

Wright, Tom (2009) ‘Indonesia dilutes antigraft court’, Wall Street Journal, 30 September. Yunto, E. (2008) ‘Mencermati pemberian SP3 kasus korupsi [Examining the cessation of

police investigations in corruption cases]’, Hukumonline, 25 November.