Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 23:06

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

The Nature and Origins of Students' Perceptions of

Accountants

Steven C. Hunt , A. Anthony Falgiani & Robert C. Intrieri

To cite this article: Steven C. Hunt , A. Anthony Falgiani & Robert C. Intrieri (2004) The Nature and Origins of Students' Perceptions of Accountants, Journal of Education for Business, 79:3, 142-148, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.79.3.142-148

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.79.3.142-148

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 154

View related articles

n recent years, the decline in numbers of accounting students has caused serious concern in the accounting pro-fession. According to the Taylor Study (2000), sponsored by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA), the percentage of college stu-dents majoring in accounting decreased from 4% in 1990 to 2% in 2000, and the percentage of high school students plan-ning to major in accounting decreased from 4% in 1990 to 1% in 2000. The seriousness of this perceived problem can be seen in the AICPA’s recent announcement that it is launching a major advertising campaign to attract new students to the profession.

Albrecht and Sack (2000) indicated several causes for this downturn, includ-ing more attractive career alternatives, misinformation, and lack of information about accounting careers. Major sources of this misinformation were high school and college accounting teachers who focused on the bookkeeping and score-keeping aspects of accounting. This emphasis may cause college accounting programs to attract the “wrong” kind of students—those who believe that accounting is a routine, numbers-crunch-ing profession (Albrecht & Sack, 2000; Davidson & Etherington, 1995). People who enter the accounting profession must be aware of many other qualities crucial for business success.

As accountants’ roles have changed, so have the qualities that they should possess. Siegel (2000) found that

accountants’ roles had changed from “number crunchers and financial histo-rians to business partners and trusted advisors” (p. 71). Myers (2002), in interviews with several accountants who had assumed the role of chief financial officer (CFO), found that they were expected to be creative, motivat-ing, energetic, and versatile individuals, with strong communication and man-agement skills. Bob Darretta, CFO of Johnson & Johnson, stressed the neces-sity for strong interpersonal skills and indicated that his company has a “lead-ership development program, not an accountant development program” (Williams & Hart, 1999, p. 37).

Although top management generally has been aware of these changes in

accountants’ roles, many accountants indicate that first-line operating and management staff often view the accountant as a bean counter and corpo-rate policeman (Siegel, 2000). Those who major in other business disciplines will be the co-workers of the accounting professionals. If they have an image of accountants as nerdish, nonpersonable numbers crunchers, accountants will have a more difficult time accomplish-ing the tasks expected of them by high-er administration.

A number of studies (Inman, Wen-zler, & Wickert, 1989; Paolillo & Estes, 1983; Seamann & Crooker, 1999) have dealt with students’ perception of the accounting profession. However, in this study we examine perceptions regarding the accounting professional, not the pro-fession. This is important because indi-viduals may select careers according to the stereotypes they hold of persons in those careers (DeCoster, 1971). Stu-dents consider whether they would want to work with such people and how being accountants themselves would affect their self-image.

Several studies have dealt with the issue of stereotypical views of accoun-tants. Parker (2000, p. 50) noted the “common stereotype of the accountant— usually portrayed as male—introverted, cautious, methodical, systematic, anti-social and, above all, boring!” There has been little change since DeCoster’s (1971) finding that accountants were viewed as “impersonal, quantitative,

The Nature and Origins of Students’

Perceptions of Accountants

STEVEN C. HUNT A. ANTHONY FALGIANI

ROBERT C. INTRIERI

Western Illinois University Macomb, Illinois

I

ABSTRACT. In this research, the authors examined accounting and nonaccounting majors’ impressions of accountants through a survey listing 58 characteristics. The results show that many students stereotypically per-ceived accountants as numbers crunch-ers and that nonaccounting majors held more negative perceptions of accoun-tants than did accounting majors. Accountants generally were seen as professional but not particularly per-sonable. The authors also examined the sources of those impressions. Among all majors, impressions formed from exposure to movies, television, and accounting courses were more negative than impressions based on relationships with accountants whom they knew. The authors discuss ways to improve the image of accountants.

inflexible, orderly, and introverted” (p. 40). Unfortunately, research on how these stereotypes arose has not been undertaken. Bougen (1994) noted that such stereotypes are not totally negative but may be inconsistent with current expectations of accountants. For exam-ple, Imada, Fletcher, and Dalessio (1980) found that practicing accountants had different perceptions of accountants than did nonaccounting students.

A majority of studies focusing on the stereotypical views of accountants in movies and fiction report generally neg-ative representations of accountants. Holt (1994) found that accountants were portrayed as lacking in communi-cation skills and ethics. Although they were portrayed as flexible, they were shown using this skill for illegal or unethical purposes. Similarly, Smith and Briggs (1999) found that accoun-tants in film and fiction were portrayed as lacking in communication skills, ethics, and flexibility. Accountants were also portrayed as devious, timid, and incompetent. Beard (1994) found that they were portrayed as socially inept but expert in their fields and that some were shown using their expertise for criminal purposes. These results should be dis-turbing to a profession that values ethi-cal behavior and communication skills.

Cory (1992) analyzed a number of works of fiction, plays, television shows, and films and determined that the image of accountants was over-whelmingly negative. However, a sur-vey of college freshmen found that although their image of accountants was worse than that of lawyers, bankers, and marketing managers, it was not negative overall (Cory, 1992). A more recent study (Dimnick & Felton, 2000) found that although accountants’ overall image in films was poor, the films that they reviewed contained more positive portrayals of accountants than the films in previous studies.

Cory (1992) pointed out that negative stereotypes could be modified through contact with an individual who did not resemble the stereotype. Davidson and Etherington (1995) and DeCoster and Rhode (1971) examined the personali-ties of actual accountants and deter-mined that the common stereotypes of accountants were inaccurate.

The introductory accounting course is a crucial factor in attracting quality students to accounting (Cohen & Hanno, 1993; Geiger & Ogilby, 2000). Seamann and Crooker (1999) found that the first accounting course did not improve students’ views of the profes-sion and thus did not cause them to be more likely to major in accounting.

We had several important purposes for this research. First, we sought to identify students’ perceptions of ac-countants overall and of the various qualities that they possessed at the time of their selection of a college major. This study extends previous research by examining a broader range of qualities and comparing accounting students with a number of other majors.

A second purpose of our research was to determine perceptions linked to various sources: film and television, accounting classes, and contact with accountants. This step is essential; one must identify how negative perceptions arise to determine how to combat them effectively. Using students’ perceptions of accountants at the time that they decided on a major, rather than their current perceptions, expands previous research.

A third purpose was to determine when (in high school, early in their college years, etc.) students select majors. This information may be useful in promoting careers in all business professions.

We also sought to demonstrate a methodology that may help researchers in other disciplines determine which stereotypes exist among students and how they originated. The methodology that we employed in this study should be useful in determining whether vari-ous majors have reasonable expecta-tions regarding the qualities prized by employers. Knowledge of how their discipline is viewed by those in other majors may help university depart-ments determine how to attract desir-able students.

Method

We constructed a four-part survey and distributed it to Principles of Accounting I and II, Introductory Mar-keting, Introductory Finance, Legal

Environment of Business, and Interme-diate Accounting I classes at Western Illinois University during the first 2 1/2 weeks of the semester. Sophomores or first-semester juniors generally take these courses. Our objective was to reach students early in their business courses to reduce influences from their classes and to increase their ability to reflect on the impressions that they held at the time that they chose a major. The choice of classes also enabled us to reach a broad spectrum of business stu-dents, because finance, marketing, and the legal environment of business are subjects in the core business curriculum at the University. The University is a medium-sized, public university with AACSB-accredited programs in busi-ness and accounting. We distributed the survey to classes on the main campus and an extension campus, which increased the diversity of students reached. Most faculty members either made completion of the survey a course requirement or provided extra credit for doing so. Thus, the response rate was close to 100%.

The first part of the instrument sought demographic information from the participants. Students identified their class status (freshman, sopho-more, etc.). Nonaccounting majors were asked to identify themselves as finance, marketing, management, information management, nonbusiness, undecided business, or undecided non-business. Nonbusiness students were asked to provide their major. Respon-dents were asked at what period in their lives they had decided on a major: (a) in high school or earlier, (b) after high school but before college, (c) dur-ing their first 2 years of college, or (d) in their junior or senior year of college. The latter category was necessary because some students with degrees in other areas were returning to school.

Impressions of Individual Qualities of Accountants

In section 2 of the survey, we listed terms that might describe an accountant. Using a 7-point scale, each student rated how accurately each of 58 items described his or her impression of accountants at the time that he or she

decided on a major. Students were asked to do this in each of four columns repre-senting different sources of the impres-sion: Movies/ TV, Accountants You Knew, Accounting Courses, and All Sources. Most of the descriptive terms used were selected from previous studies (Beard, 1994; Cory, 1992; DeCoster & Rhode, 1971; Dimnick & Felton, 2000; Holt, 1994; Seamann & Crooker, 1999). We added other terms for a broader range of personal qualities.

Overall Impressions of Accountants

Students rated their overall impres-sion of accountants at the time that they decided on a major, indicating each of four sources (Movies/TV, Personal Knowledge of Accountants, Accounting Classes, These and Other Sources Com-bined). Respondents also listed other sources of their impressions. In addi-tion, students were asked if they had taken accounting in high school. The final question asked accounting students only to indicate on a 7-point scale how confident they were that they had cho-sen the right major.

Results

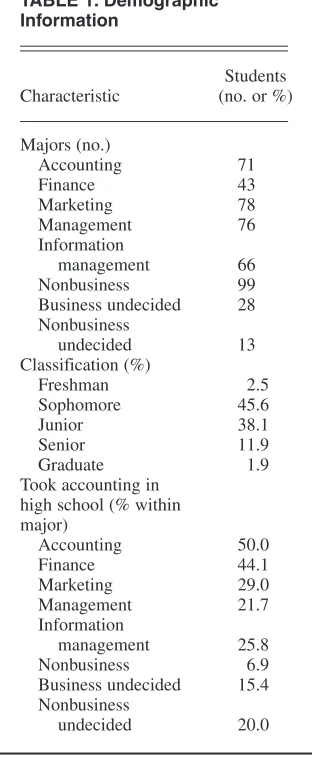

We received 474 responses. Respon-dents included 71 accounting majors, 43 finance majors, 78 marketing majors, 76 management majors, 66 information management majors, 99 nonbusiness majors (students majoring in agriculture, law enforcement, and several other areas), 28 students who were undecided as to what area of business in which to major, and 13 nonbusiness students who were undecided. The majority of students identified themselves as sophomores or juniors. Demographic data are presented in Table 1.

Most students decided on a major dur-ing their first 2 years of college. These results are similar to those of Herman-son, HermanHerman-son, and Ivancevich (1995). Unlike those researchers, however, we found that accounting majors decided earlier than other majors. Almost half of the accounting majors decided on their major before starting college. This early decision may have been influenced by their having taken accounting in high school (half of the accounting majors had

done so), whereas the other subjects are rarely offered in high school. The fact that other business students took longer

to decide on a major could signal an opportunity for accounting instructors to alert such students to the benefits of a career in accounting.

Students indicated that they had, on average, made their major decisions approximately 1 year earlier. The re-sponses of those who had made their decisions earlier did not differ signifi-cantly from the responses of those who decided more recently. Accounting majors showed a reasonable level of confidence that they had selected the right major, with a mean of 5.63 (with 7 representing the highest level).

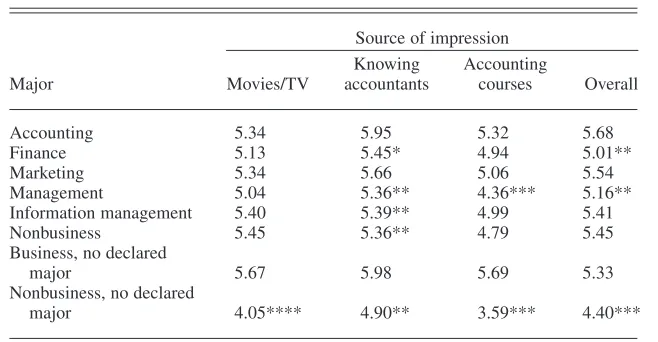

Overall Impression Scores

We performed multiple comparison least significant difference (LSD) tests in conjunction with analyses of variance (ANOVAs) to compare the overall scores for accountants with those of other groups of students. We show these scores in Table 2. Respondents’ overall views of accountants at the time of deciding on a major were lower for all majors (and undecided students) than for accounting majors (p < .001). Nonaccounting ma-jors’ impressions of accountants overall were between 4.34 and 4.96, on a 7-point scale (with 7 representing a very positive impression), whereas accounting stu-dents’ overall impressions averaged 5.72. Among the respondent groups, students majoring in finance had the least positive view of accountants. This is critical

TABLE 1. Demographic Information

Students Characteristic (no. or %)

Majors (no.)

Accounting 71

Finance 43

Marketing 78 Management 76 Information

management 66 Nonbusiness 99 Business undecided 28 Nonbusiness

undecided 13 Classification (%)

Freshman 2.5

Sophomore 45.6

Junior 38.1

Senior 11.9

Graduate 1.9

Took accounting in high school (% within major)

Accounting 50.0

Finance 44.1

Marketing 29.0 Management 21.7 Information

management 25.8 Nonbusiness 6.9 Business undecided 15.4 Nonbusiness

undecided 20.0

TABLE 2. Respondents’ Mean Overall Impressions of Accountants

Source of impression Knowing Accounting

Major Movies/TV accountants courses Overall

Accounting 4.47 6.21 5.81 5.72

Finance 3.94* 4.66**** 4.55**** 4.34**** Marketing 3.86 ** 5.16**** 4.37**** 4.69**** Management 4.48 5.38**** 4.35**** 4.71**** Information management 4.11 5.16**** 4.16**** 4.69**** Nonbusiness 3.98** 5.14**** 4.72**** 4.86**** Business, no declared

major 4.50 5.52**** 5.32 4.96***

Nonbusiness, no declared

major 3.75 5.52 4.70**** 4.89****

Notes. Means are on a scale ranging from 1 (most negative impression) to 7 (most positive impres-sion). Significance levels from least significant difference (LSD) multiple comparisons tests are as follows: *Significant at .1 level, **significant at .05 level, ***significant at .01 level, and ****sig-nificant at .001 level.

information because finance and ac-counting often compete for the same finite pool of students.

We found similar results for two of the three other sources of impressions regard-ing accountants, personal knowledge of accountants and accounting classes that students have taken. However, the catego-ry focusing on movies and television showed significant differences between accounting majors and only three groups: finance, marketing, and nonbusiness majors. Impressions formed from having taken accounting courses were more neg-ative than those formed through acquain-tance with accountants, for all majors (including accounting). Impressions formed through watching movies and television were more negative than those formed through having taken accounting courses but still hovered around the mid-point of the 7-mid-point scale. Overall impres-sions of accountants appear to have been enhanced by acquaintance with accoun-tants. Relatively negative impressions based on movies and television did not dissuade students from majoring in ac-counting, apparently because of the very positive impressions formed through respondents’ personal relationships with accountants. Accounting students also exhibited high scores for impressions formed from accounting courses. These results are shown in Table 2.

Students were asked to name other sources of information contributing to their impressions of accountants at the time that they decided on a major. Only about 16% of students noted any other sources, with finance students the least likely (9%) to do so and management students (23%) the most likely. Eigh-teen percent of accounting students named other sources. No other source was named by more than 10 students. Among the more common other sources of information were parents and other family members (mentioned by 9), books (8), nonaccounting teach-ers and classes (7), friends (6), maga-zines and newspapers (6), and other students (4). Parents, teachers, and friends were important influences on major selection in Hermanson et al. (1995) and Dodson and Price (1991). Albrecht and Sack (2000) considered advisors to be a major source of misin-formation about accounting careers,

but advisors were mentioned by only two respondents.

Individual Qualities

Respondents evaluated each of 58 qualities or characteristics in terms of how well they corresponded to their impressions based on each of the four sources. Analysis of these responses yielded some interesting results regard-ing stereotypical views of accountants. Although accountants were seen widely as skilled in math and tax work and attentive to detail, they were not considered particularly admirable, excit-ing, outgoexcit-ing, versatile, or strong in leadership capabilities. These results are consistent with a stereotype of the accountant as a passive, inflexible num-bers cruncher. Examination of individ-ual qindivid-ualities revealed that accountants were not seen as devious, although they did not rank high in sincerity.

Results were mixed as to whether accounting students themselves accept-ed the stereotype regarding accountants. Analysis of individual items comprising the factors shows that accounting stu-dents, like most of the other groups, gave accountants very high scores for being good at math and detail-oriented work. Albrecht and Sack (2000) indicat-ed that both of these perceptions were part of an incorrect image regarding qualities needed in accounting, an image that has been causing the wrong people to choose accounting as a major. Accounting students also showed some-what lower scores for flexibility and writing ability than the profession may prefer. On the other hand, accounting students’ high scores for “gives good business advice” indicate their aware-ness that accountants do more than crunch numbers. High ratings for lead-ership attributes indicate that the accounting students rejected the stereo-type of accountants as passive loners. The high ratings for the ethical descrip-tor should provide hope that the profes-sion is attracting people of good charac-ter. Unfortunately, the characteristics “gives good business advice,” “ethical,” and “being a leader” were given signifi-cantly lower scores by nonaccounting students compared with accounting stu-dents. This implies that accounting

majors hold a very different image of accountants than do other people.

Our results consistently show less favorable impressions of accountants among finance majors than among accounting majors. Analysis of individ-ual qindivid-ualities shows that finance majors rated accountants lower on risk taking than did any other group. It has been suggested (Albrecht & Sack, 2000) that finance majors reject the safe, secure approach of accounting. They see themselves willing to take career risks on the assumption that if one career stalls, they will begin another. Albrecht and Sack (2000) also suggested that this belief was fostered by years of eco-nomic growth. With recent ecoeco-nomic downturns, students may soon see accountants’ allegedly more conserva-tive methods and approach in a more positive light.

Factor Analysis

Factor analysis of judgment source rat-ings. We submitted questionnaire data from each judgment source for factor analysis, using identical criteria and rotation methods so that the data could be summarized and organized conceptu-ally. We performed common factor analysis (CFA) using squared multiple correlations (SMC) in the diagonals of the correlation matrix. Factors were identified in three ways. First, we ini-tially retained for further consideration all factors that obtained an eigenvalue greater than one. Second, we applied a scree test or scree plot (Cattell, 1966) to identify factors that decreased in size in a less consistent manner. Third, we con-sidered the variance accounted for by each factor and its interpretability. Through these criteria, we identified four initial factors and submitted them for further analysis using an oblique-promax rotation to simple solution. Items loaded on a factor if they had a value of .5 or better. Factor loadings of .5 or larger were considered conserva-tive estimates and significantly related to a factor. Items with loadings less than .5 were considered uninterpretable and dropped from further consideration. We made comparisons of the factor struc-ture for each judgment source to ensure coherence and interpretability of the

factors by imposing additional criteria. Each item had to load at .5 or better on one factor and could not load on the sec-ond factor at .4 or higher, and each item had to load on all four judgment sources. Further, factors with less than three items with loadings above a spec-ified criterion (in this case .5) are usual-ly regarded as trivial. These were dropped from further consideration (see Gorsuch, 1983). We applied this final criterion because factors or subscales with less than 3 items are typically more unreliable than subscales or factors with 3 or more items (Nunnally, 1968).

These criteria yielded two factors that were structurally similar and stable across judgment sources. Factor 1 con-sisted of 18 items: organized, ethical, attentive to detail, financially success-ful, gives good business advice, analyt-ic, professional, responsible, good at math, intelligent, sensible, competent, well dressed, efficient, knows taxes, thorough, computer literate, and percep-tive. Conceptually these items represent a Professionalism factor. Factor 2 con-tained 12 qualities: exciting, outgoing, creative, admired, a leader, persuasive, witty, charismatic, flamboyant, ener-getic, versatile, and unconventional. Conceptually these items represent a Personability factor.

The components of these factors are reasonably consistent with Parker’s (2000) and DeCoster’s (1971) studies of the accounting profession, as well as Beard’s (1994) study of portrayals of accountants in films. Those studies, however, looked at a limited number of individual qualities, not factors.

Factor scores. Factor scores were gen-erated as a way to limit the subset of variables submitted for further analysis. We created factor scores by summing the raw scores for each item that loaded on the factor and dividing by the num-ber of items. Participants with missing data were included in the analysis if they had no more than two missing items per factor. In these cases, we cre-ated factor scores by summing the avail-able number of items and dividing by them. This procedure is a consistent and acceptable method for summarizing data (Harman, 1976).

Factors 1 (Professionalism) and 2

(Personability) differed in that Factor 1 had relatively high scores (around 5) across the four sources of impressions, whereas Factor 2 scores were lower, typically positioned around the mid-point of 4. This difference indicates that accountants were widely viewed as pro-fessional but not seen as being particu-larly personable. This is consistent with the stereotype of the accountant as a competent but socially inept loner.

For both factors, the highest means were found for impressions based on acquaintance with accountants and the lowest were found for impressions formed through accounting courses. For Professionalism, accounting students’ impressions based on movies/TV did not differ significantly (using LSD mul-tiple comparisons tests) from those of other majors, except for nonbusiness undecided students. On the other hand, for impressions formed through “accountants known,” accounting stu-dents scored significantly higher than all other majors except marketing and “business undecided” (the latter having a higher mean than accounting stu-dents). For accounting courses, only management and “nonbusiness unde-cided” students had means significantly different from accounting students. Overall, finance, management, and “nonbusiness undecided” students had significantly different means than

ac-counting students. We provided this information in Table 3.

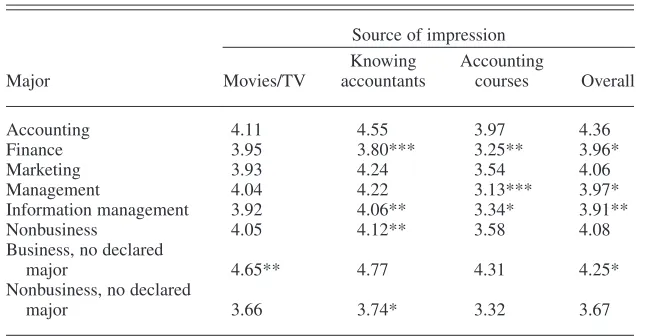

For Personability, regarding impres-sions formed from watching movies/TV, accounting students differed significantly only from undecided business students, who had more positive impressions of accountants. Finance, in- formation man-agement, undecided nonbusiness, and nonbusiness majors differed from accounting majors in the category regard-ing impressions formed through knowregard-ing accountants. Finance, information man-agement, and management students had significantly different impressions formed through accounting courses than did accounting students, as evidenced by the posthoc comparisons. Overall impressions of accountants were signifi-cantly different for finance, management, information management, and undecided nonbusiness students compared with accounting majors, according to posthoc follow-up tests. See Table 4 for more information.

Discussion

The results of this study provide evi-dence regarding the impressions held by various groups of college students regarding accountants as perceived by those students at the time that they selected a college major. Our study also examined the sources of those

impres-TABLE 3. Respondents’ Mean Impressions of Accountants: Factor 1 (Professionalism)

Source of impression Knowing Accounting

Major Movies/TV accountants courses Overall

Accounting 5.34 5.95 5.32 5.68

Finance 5.13 5.45* 4.94 5.01**

Marketing 5.34 5.66 5.06 5.54

Management 5.04 5.36** 4.36*** 5.16**

Information management 5.40 5.39** 4.99 5.41

Nonbusiness 5.45 5.36** 4.79 5.45

Business, no declared

major 5.67 5.98 5.69 5.33

Nonbusiness, no declared

major 4.05**** 4.90** 3.59*** 4.40***

Notes. Means are on a scale ranging from 1 (most negative impression) to 7 (most positive impres-sion). Significance levels from least significant difference (LSD) multiple comparisons tests are as follows: *Significant at .1 level, **significant at .05 level, ***significant at .01 level, and ****sig-nificant at .001 level.

sions. The positive impressions regard-ing accountants’ professionalism are good news for the profession. Impres-sions were considerably more negative in the area of personability. Given expectations of accounting in today’s business world, this represents a prob-lem. We found some evidence of an accounting stereotype, as respondents saw accountants as inflexible, unexcit-ing, and detail oriented. Nonaccounting business students and nonbusiness stu-dents held considerably less positive views of accountants than did account-ing majors, which could color nonac-countants’ future interactions with those who choose the accounting profession.

We must ask the important question, Why are accounting programs losing students? Many good students may be turning to other business areas, such as finance or information management, because of such stereotypical negative views of accountants. Therefore, our results are consistent with the following conclusion of Albrecht and Sack (2000): The number of accounting majors is declining nationwide partly because of misinformation and myths about accountants.

The finding that both accounting and nonaccounting students had relatively negative impressions of accountants based on their portrayal in movies and television indicates that the negative stereotypes presented in these media

do not serve as a major factor in dri-ving potential accounting students away. This is good news for the profes-sion, because such media stereotypes may be harder for the profession to change than impressions formed through taking accounting courses and knowing accountants personally.

Albrecht and Sack (2000) stressed the need to improve introductory ac-counting courses to show how accoun-tants can be creative, problem-solving professionals. In the current study, nonaccounting majors’ impressions formed through having taken account-ing classes were relatively negative. For all groups of nonaccounting majors, impressions formed through taking accounting courses were considerably less favorable than those obtained through personal knowledge of accoun-tants. This discrepancy indicates that the profession is missing a major oppor-tunity to change or reduce some nega-tive impressions before students choose nonaccounting majors, a finding that is consistent with Seamann and Crooker (1999). The finding that personal knowledge of accountants generally resulted in more positive impressions of accountants than did accounting cours-es implicours-es that providing direct contact with accountants through classroom visits or special career day events may improve students’ perceptions of accountants.

In a major contribution to the relevant research, in this study we used a set of 58 possible personal characteristics of accountants and reduced them to two specific constructs comprising 30 items. The two domains of interest were labeled Professionalism and Personabil-ity. Data analysis demonstrated that accountants were perceived in a more favorable way for their professionalism than for their personability. Consistent with respondents’ overall results, we found that means were most favorable for impressions based on knowing accountants (for both factors). However, our results show that the least favorable scores in the overall evaluations corre-sponded to impressions formed through taking accounting courses rather than impressions formed through watching movies and TV.

Results were mixed with regard to Albrecht and Sack’s (2000) assertion that the wrong students were majoring in accounting. Although accounting stu-dents viewed some parts of the account-ing stereotype to be typical of accoun-tants, they also found accountants to be leaders who give good business advice. This finding provides further evidence that accounting students have a better understanding of the qualities needed by a successful professional than previ-ously thought.

Another important question is, How can these results be applied to a real-world setting? The results of this study should be helpful in diagnosing negative views of accountants and the individuals who hold them. Qualities on which accountants are improperly given low scores should receive attention in efforts to improve the profession’s image. If accountants are seen as unexciting and lacking leadership potential, it will be difficult to attract high quality students to the profession. Stressing the decision-making and communication skills re-quired of today’s accounting profession-als is needed in both secondary and postsecondary accounting education.

This study has several limitations. The high level of satisfaction with the major chosen among accounting stu-dents could be explained partly by cog-nitive dissonance, an effect that causes a choice to be viewed as more desirable after one has selected it. However, as

TABLE 4. Respondents’ Mean Impressions of Accountants: Factor 2 (Personability)

Source of impression Knowing Accounting

Major Movies/TV accountants courses Overall

Accounting 4.11 4.55 3.97 4.36

Finance 3.95 3.80*** 3.25** 3.96*

Marketing 3.93 4.24 3.54 4.06

Management 4.04 4.22 3.13*** 3.97*

Information management 3.92 4.06** 3.34* 3.91**

Nonbusiness 4.05 4.12** 3.58 4.08

Business, no declared

major 4.65** 4.77 4.31 4.25*

Nonbusiness, no declared

major 3.66 3.74* 3.32 3.67

Notes. Means are on a scale ranging from 1 (most negative impression) to 7 (most positive impres-sion). Significance levels from least significant difference (LSD) multiple comparisons tests are as follows: *Significant at .1 level, **significant at .05 level, and ***significant at .01 level.

Lawler, Kuleck, Rhode, and Sorenson (1975) noted, the effects of cognitive dissonance tend to disperse within a year. According to our data, a majority of students made their choice of major a year or more earlier.

The students’ ability to recall ac-counting-related impressions that they held during the time that they were deciding on a major may be an issue; the students could have been stating their current impressions instead. How-ever, we noted no significant differences between responses of those who had decided on their majors recently and those who decided several years earlier, so this concern did not appear to influ-ence our results in a problematic way.

At the time this research was con-ducted, Andersen and Enron had yet to become household words. It is likely that students deciding on a major now may consider news reports about accountants and auditors. However, this makes a key conclusion of this study: Students need to interact with real accountants to dispel negative images from other sources, even more crucial. Students then may understand that most accountants are honest, competent, and hard-working. Accounting scandals may have helped improve certain as-pects of accountants’ images. Account-ants are more likely to be seen as high-ly paid and powerful.

Future research could involve the dis-tribution of similar surveys in high schools and freshman classes in college. Administering the survey to high school and community college accounting teachers and advisers might help in devising ways to offset negative stereo-types of accountants.

Performing similar research in a vari-ety of academic settings should increase the external validity and consequent generalizability of these findings.

Fu-ture research could determine the effect of recent accounting scandals on stu-dents’ perceptions of accountants at the time that they select their majors. A new source of impressions, reports from news media, could be added.

This research dealt with student impressions of accountants at the time that they selected a major. We did not test directly how these impressions affect major choice. Such tests could be a valuable extension in determining the degree to which perceived qualities of accountants—as opposed to the profes-sion itself and the salaries, work loads, and professional certifications—affect such decisions.

REFERENCES

Albrecht, W. S., & Sack, R. J. (2000). Accounting education: Charting the course through a per-ilous future. American Accounting Association Accounting Education Series, 16.

Beard, V. (1994). Popular culture and professional identity: Accountants in the movies. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 19(3), 303–318. Bougen, P. D. (1994). Joking apart: The serious

side to the accountant stereotype. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 19(3), 319–335. Cattell, R. B. (1966). The scree test for the

num-ber of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1(2), 245–376.

Cohen, J., & Hanno, D. M. (1993). An analysis of underlying constructs affecting the choice of accounting as a major. Issues in Accounting Education, 8(2), 219–237.

Cory, S. N. (1992). Quality and quantity of accounting students and the stereotypical accountant: Is there a relationship? Journal of Accounting Education, 10(1), 1–24.

Davidson, R. A., & Etherington, L. D. (1995). Personalities of accounting students and public accountants: Implications for accounting edu-cators and the profession.Journal of Account-ing Education, 13(3), 425–444.

DeCoster, D. T. (1971). Mirror, mirror on the wall. The CPA in the world of psychology. Journal of Accountancy, 132(2), 40–45.

DeCoster, D. T., & Rhode, J. G. (1971). The accountant’s stereotype: Real or imagined, deserved or unwarranted. The Accounting Review, 66(4), 651–664.

Dimnick, T., & Felton, S. (2000). The image of the accountant in popular cinema.Paper presented

at the American Accounting Association Annu-al Meeting, Philadelphia.

Dodson, N. J., & Price, J. C. (1991). Who is tomor-row’s CPA? Ohio CPA Journal, 50(4), 9–14. Geiger, M. A., & Ogilby, S. M. (2000). The first

course in accounting: Students’ perceptions and their effect on the decision to major in account-ing. Journal of Accounting Education, 18(1), 63–78.

Gorsuch, R. L. (1983). Factor analysis(2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis

(3rd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Hermanson, D. R., Hermanson, R., & Ivancevich, R. H. (1995). Are America’s top business stu-dents steering clear of accounting? The Ohio CPA Journal, 54(2), 26–30.

Holt, P. E. (1994). Stereotypes of the accounting professional as reflected by popular movies, accounting students, and society.New Accoun-tant, 9(7),24–25.

Imada, A. S., Fletcher, C., & Dalessio, A. (1980). Individual correlates of an occupational stereo-type: A reexamination of the stereotype of accountants. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65(4), 436–439.

Inman, B. C., Wenzler, A., & Wickert, P. D. (1989). Square pegs in round holes: Are accounting students well-suited to today’s accounting profession? Issues in Accounting Education, 4(1), 29–47.

Lawler, E. E. III, Kuleck, W. J., Rhode, J. E., & Sorenson, J. E. (1975). Job choice and post-decision dissonance. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 14(1), 217–226. Myers, R. (2002). How CFOs stretch boundaries.

Journal of Accountancy, 193(5), 75–81. Nunnally, J. C. (1968). Psychometric theory.New

York: McGraw-Hill.

Paolillo, J. G., & Estes, R. W. (1983). An empiri-cal analysis of career choice factors among accountants, attorneys, engineers, and physi-cians. The Accounting Review, 57(4), 785–793. Parker, L. (2000). Goodbye, number cruncher!

Australian CPA, 77(2), 50–52.

Seamann, G. P., & Crooker, K. J. (1999). Student perceptions of the profession and its effect on decisions to major in accounting. Journal of Accounting Education, 17(1), 1–22.

Siegel, G. (2000). The image of corporate accoun-tants. Strategic Finance, 82(2), 71–72. Smith, M., & Briggs, S. (1999). From

bean-counter to action hero: Changing the image of the accountant. Management Accounting

(U.K.),77(1), 28–30.

Taylor Research & Consulting Group, Inc. (2000).

Student and academic research study: Final quantitative report. New York: AICPA. Williams, K., & Hart, J. (1999). Bob Darretta:

Developing financial leaders at J & J. Strategic Finance, 81(4), 36–41.