Changing minor rural road networks in relation to landscape

sustainability and farming practices in West Europe

F. Pauwels

∗, H. Gulinck

Institute for Land and Water Management, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Vital Decosterstraat 102, B-3000 Leuven, Belgium

Accepted 19 July 1999

Abstract

Use and characteristics of the minor rural road network have changed dramatically in West-European intensive agricultural landscapes. These changes are caused by modern agriculture, by changing values of the road’s verges and by the multifunc-tionalization of the rural landscape. Changing the network, conventional farming practices often decrease landscape ecological stability. These problems can be tackled by managing the road-verge network as an integrated subsystem of the landscape. A multifunctional management can reconcile transport, biological and recreational functions of the rural road-verge network. ©2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Minor rural road network; Agricultural transport; Landscape planning; Landscape ecology; West Europe

1. Introduction

The minor rural road network is an important part of the landscape structure. It sustains all agricultural activities by connecting farms and fields, market or processing industries (output) and input resources. Roads and their adjoining verges are important ele-ments of the ecological infrastructure and influence landscape-ecological patterns and processes. The rural road system conditions the development perspectives of agriculture and recreation, as well as some possi-bilities of agriculture-related preservation of scenery and nature (Michels and Jaarsma, 1988, pp. 11–12). The distribution and the type of roads also determine the pattern, intensity and character of agricultural

∗Tel.: +32-11-269175; fax: +32-11-269019

E-mail address:[email protected] (F. Pauwels)

transport. On the other hand, the road network is adapted to the changing demands of agricultural transport. Different farming systems have different transport needs, use other transport facilities, and pro-duce different traffic patterns (Gulinck and Pauwels, 1993).

This papers aims to show briefly that conventional agriculture also affected use and characteristics of the minor rural road network, with specific repercussions for landscape sustainability. Changed use and values of the associated road verges and of the rural landscape as a whole, create new problems and demands with respect to landscape sustainability. Therefore, assess-ment of landscape sustainability in relation to farming practices should tackle the road networks’ use. Finally, the paper presents, from the author’s experience in the fertile loess area of Belgium, West Europe, rec-ommendations for landscape management in relation to minor rural roads and their use.

2. Changes in the minor rural road network: conflicts and sustainability of the landscape

In many European regions, structure and use of the minor rural road network have been changing rapidly during last decades. Three groups of changes can be distinguished:

1. Changes in agricultural transport and a consequent demand for upgraded roads.

2. Changes in management of, and impacts on road verges.

3. A ‘multifunctionalization’ of the minor rural road network.

These changes often lower landscape and nature qualities and increase conflicts between the different user groups of roads and verges.

2.1. Agricultural transport

The first group of changes mainly take place in agricultural landscapes with intensive farming prac-tices. The volume of fertilizers which is transported to the fields, the frequency of pesticide-use, and the volume of crops transported from the fields to the farm or directly to the processing industries (e.g. the sugar factory), have increased dramatically. Farmers use machinery and transport vehicles with larger dimensions and weight to reduce the number of transports. However, the traditional tertiary, un-paved roads are too narrow and not suitable to carry the large transport weight. These roads are aban-doned or adapted to modern agricultural transport requirements.

At the same time, small fields are often clustered to large units so that roads lose their function and disap-pear as part of the field. Higher inputs, higher yields and larger fields result in a higher volume to transport and often in a more intensive traffic on the remaining road segments. These remaining road segments are, consequently, paved or metalled with bitumen or con-crete, and widened at the cost of their verges. The in-tensified traffic can have an important negative impact on verge qualities.

These changes in the road network can sponta-neously continue for many years and even decades, or can be systematically accomplished in a few years by a traditional land consolidation programme. In these

projects, road improvement is often a major part of the ‘optimization’ of the landscape for agriculture. As a result, the dense network of unpaved, narrow roads is replaced by a network with wider mesh size and wider, concrete or bitumen roads. These structural landscape changes force some landscape-ecological processes to function in a different way. Four prin-ciples of interaction between these processes and agricultural roads and transport can be distinguished (Gulinck and Pauwels, 1993):

– Association (e.g. linear biotopes, lines of

concen-trated water runoff, verge as talus in erosion con-trol).

– Distribution (e.g. fertilizers, organisms, seeds, soil).

– Separation (e.g. barrier against flow of pesticides, barrier for organism dispersal).

– Disturbance (e.g. traffic noise and vibrations). The landscape as it was, is destabilized until a new balance is reached. It is likely that the new, more ho-mogenous landscape has less appreciated landscape qualities and a smaller capacity for nature and agri-cultural production.

2.2. Road verges: management and impacts

Verges are undoubtedly vulnerable ecosystems. The intensified use of pesticides and fertilizers increased contamination and eutrophication of the adjacent, un-buffered verge ecosystem. On the other hand, verges become more important for nature conservation and development as the nature contents of the agricultural landscape matrix became increasingly impoverished. In intensive agricultural landscapes, verges can be im-portant refuge for fauna and flora (Kleyer, 1989; Bunce and Heal, 1990; Sykora et al., 1993). As verges host many organisms important to stabilize the agroecosys-tem, the loss of these verges can lead to more pests, and a less sustainable farming system (Sykora et al., 1993). The ecotope boundaries road-verge-field be-came sharper (almost no ecotone) and the microgra-dients within each ecotope disappear.

2.3. Multifunctionalization

Nowadays, it is widely recognized that food produc-tion is not the only important funcproduc-tion of the rural land-scape. The growing urban population has increased mobility. People have more leisure time, and recre-ation in the rural landscape is increasingly popular. Urban people start living in rural areas. All these user groups enter the landscape, using the same road net-work. Intensified fast car traffic does not match with slow agricultural transportation. Narrow, winding ru-ral roads are not designed for car traffic. At the same time, biodiversity, nature conservation and a healthy, clean environment are recognized as important rural landscape functions, and must be accounted for in all planning and management activities. Intensified car and agricultural traffic can threaten verge qualities for nature, directly by noise, vibrations, collisions and pollution (Sykora et al., 1993), and indirectly by road works, road widening and paving or metalling with concrete or bitumen. Both, motorized transport modes conflict with nature qualities and with people walking or cycling around the landscape. The latter group does not like a drastic cut of vegetation, sometimes required by farmers to allow free passage of agricultural vehi-cles. The increased use of the rural road network by different user groups, causes many conflicts between, and even within these groups. (Pauwels, 1995)

2.4. Summary of the consequences for landscape sustainability in intensive agricultural landscapes

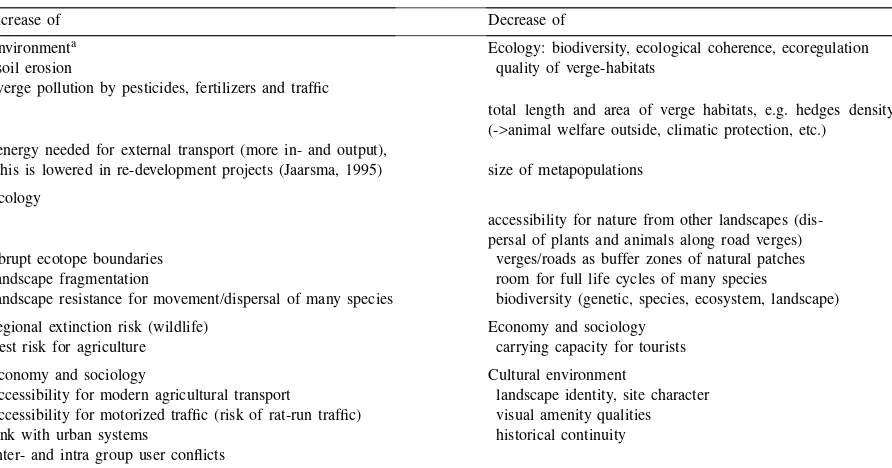

Table 1 presents possible changes in landscape qualities resulting from these alterations of the road network as caused by conventional modern farming practices. An integrated table of landscape qual-ity aspects was consulted for completing this table (Mansvelt van et al., 1995, p. 233; Mansvelt van and Lubbe van der, 1999).

3. Opportunities towards a new balance in accordance with landscape sustainability

In order to fit the minor rural road network in a multifunctional and modern use, actions should be taken at four levels: landscape, road network, individ-ual road segments and verges. Road network problems can only be tackled at a regional or municipal level. As roads and verges often are public domain, local municipalities are important actors and planning part-ners. Land consolidation projects should take into ac-count problems of multifunctionality. These projects can be an interesting instrument to revert the spon-taneous degradation of the traditional road network. They can change in a short time structure and pat-terns of landscape elements, along with simultaneous changes in their ownership and consequent responsi-bility. The farm level is important for private roads, for verge management, for road-use and use of trans-port vehicles. Individual farms have little influence on road structure and pattern. When the farmer’s fields are scattered over the landscape, actions of one or few farmers towards a road and verge use — which in-creases the landscape sustainability — have little im-pact. Nevertheless, they can save or rehabilitate some roads and verges.

Some important actions to prevent user conflicts and enhance the qualities of the minor rural road network are presented in Table 2.

4. Conclusions

Table 1

Possible consequences of changes in the minor rural road network in intensive agricultural landscapes caused by conventional farming practices

Increase of Decrease of

Environmenta Ecology: biodiversity, ecological coherence, ecoregulation

soil erosion quality of verge-habitats

verge pollution by pesticides, fertilizers and traffic

total length and area of verge habitats, e.g. hedges density (->animal welfare outside, climatic protection, etc.)

energy needed for external transport (more in- and output),

this is lowered in re-development projects (Jaarsma, 1995) size of metapopulations Ecology

accessibility for nature from other landscapes (dis-persal of plants and animals along road verges) abrupt ecotope boundaries verges/roads as buffer zones of natural patches landscape fragmentation room for full life cycles of many species

landscape resistance for movement/dispersal of many species biodiversity (genetic, species, ecosystem, landscape) regional extinction risk (wildlife) Economy and sociology

pest risk for agriculture carrying capacity for tourists

Economy and sociology Cultural environment

accessibility for modern agricultural transport landscape identity, site character accessibility for motorized traffic (risk of rat-run traffic) visual amenity qualities

link with urban systems historical continuity

inter- and intra group user conflicts

aCriteria for the development of sustainable rural landscape management, listed according to Mansvelt van and Lubbe van der, 1999, p. 40.

Table 2

Actions for sustainable landscape management in intensive agricultural landscapes with changing minor rural road networks

1. Landscape: changing land use (e.g. by re-development or land consolidation projects)

agricultural transport is determined by farm system characteristics such as location, distribution and size of fields;

crops grown/animals bred; transport facilities; soil and crop management. These characteristics can be adapted taking into account their influence on the roads’ structures and use, on the qualities of the verges, on transport pattern and intensity;

2. Network evaluation and use

evaluate the role of the road and verge segments for the different user groups: agriculture, recreation, nature (ecological infrastructure, soil conservation, etc.) (Pauwels, 1995). Use this assessment to define priorities and boundary conditions when changing the road network. A helpful tool to predict these impacts are transport models (Pauwels and Gulinck, 1991);

separate fast car and slow farm traffic: good land use planning, well-designed road networks/adapted road construction (control of transport routes for different transport modes, for example:)

‘traffic calming’: concentrating diffuse flows on minor roads at a few rural highways, resulting in a decrease of volumes and and speeds within the region (Jaarsma, 1996);

3. Use of road segments

give narrow roads a new function in other functional networks: e.g. for recreation (cycling and walking, horse-riding) or as linear nature element;

rehabilitate the agricultural function of the road by stimulating farmers to use machinery and transport vehicles with smaller

dimensions and lower weights. Farmers can also drive slowly and carefully so that narrow roads suffice. They do not need ‘highways’; stimulate agro-engineers to design farm machinery and transport vehicles that can use more easily traditional

roads (eventually slightly improved); 4. Verge management

integrate the management of verges in the farming system;

managing road verges and maintaining small roads is a part of landscape and nature production: can this be economically be valorized by paying the local farm community ?

buffer verge ecosystems (buffer zones and adapted field margin management);

planning should aim to reconcile road vs. verge func-tions, as well as the different demands of the user groups agriculture, recreation and nature. The disap-pearance or degradation of the roads annex verges, leads to more uniform and less stabile landscapes and agro-ecosystems, particularly in intensive agricultural regions. The best way to safeguard the existence of a road is to make it a part of a traffic route, even if it is as a footpath. The road’s structure may not be adapted at the cost of the verge qualities. Sustainable types of agriculture should respect a multifunctional and modern use of the minor rural road network as important subsystem of the landscape, regarding all values of both, roads and verges. Research is needed to further clarify the chorological relations between the minor road network, the roads, the verges and the surrounding rural landscape.

References

Bunce, R., Heal, O.W., 1990. Ecological changes of land use change (ECOLUC). In: Report of the Inst. of Terrestrial Ecology 1989/1990. Natural Environment Council, pp. 19–24. Gulinck, H., Pauwels, F., 1993. Agricultural transport and

landscape ecological patterns. In: Bunce, R., Ryszkowski, L., Paoletti, M. (Eds.), Landscape Ecology and Agroecosystems. Lewis Publ., London, pp. 49–59.

Jaarsma, C.F., 1995. Energy saving for traffic on minor rural roads: opportunities within re-development projects. In: Henscher D.,

King, J., Hoon Oum, T. (Eds.), World Transport Research, Proceedings of the 7th World Conference on Transport Research, vol. 3, Transport Policy. Pergamon, pp. 347–360. Jaarsma, C.F., 1996. Approaches for the planning of rural road

networks according to sustainable land use planning. In: Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Sustainable Land Use Planning, Gödöllö, September 1996, pp. 14.

Kleyer, M., 1989. Zur Ökologie linearer Landschaftselemente in einer intensiv genutzten Agrarlandschaft. Verhandlungen der Gesellschaft für Ökologie Band XIX/I.

Mansvelt van, J.D., Stobbelaar, D.J., de Graaff, J. (Eds.), 1995. Proceedings of the second plenary meeting of the EU-concerted action: The landscape and nature production capacity of organic/sustainable types of agriculture. Department of Ecological Agriculture, Agricultural University Wageningen. Mansvelt van, J.D., Lubbe van der, M.J., 1999. Checklist for

Sustainable Landscape Management. Elsevier, Amsterdam. Michels, T., Jaarsma, C.F. (Eds.), 1988. Minor rural roads.

Planning, design and evaluation. Proceedings European Workshop Minor Rural Roads, Wageningen October 1987, PUDOC, Wageningen.

Pauwels, F., 1995. Scenario studies of agricultural transport in landscape and green management planning. In: Schoute, J., Finke, P., Veeneklaas, F., Wolfert, H. (Eds.), Scenario Studies for the Rural Environment. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp. 561–565.

Pauwels, F., Gulinck, H., 1991. Transport modelling and farming system analysis for the prediction of landscape ecological impacts of agricultural changes. In: Verachtert, H., Billiet, C. (Eds.), Environmental Platform 1991, Proceedings. Katholieke Universiteit Leuven.