A checklist approach to evaluate the contribution of

organic farms to landscape quality

Juliëtte Kuiper

∗Generaal Foulkesweg 89, 6703 DA Wageningen, The Netherlands

Accepted 19 July 1999

Abstract

Criteria need to be developed to evaluate the cultural environment of European rural landscapes. The goal is to evaluate and encourage the contribution of organic farming to sustainable landscape quality.

Two sets of criteria were used to evaluate the quality of the cultural environment, non-expert and expert values. The non-expert values consisted of criteria for the appreciation of the present local landscape by users and inhabitants. These criteria were derived from psychological principles (Coeterier, 1996).

The expert values for landscape assessment were derived from physiognomy, geography and landscape architecture. These criteria require specialized knowledge essential in understanding the cultural history of at least the regional landscape and in landscape planning. The criteria were derived from a reflection of landscape plans at different scale levels (Kuiper, 1998). This reflection resulted in planning objectives based on the following three criteria: diversity; coherence; and continuity.

Diversity refers to the diversity of landscape components as an expression of the relationships between land use and abiotic features; coherence refers to coherence among landscape components as an expression of the relationships between sites (hydrology, ecology and infrastructure); continuity refers to temporal relationships of land use and spatial arrangement from the past to the future. These three criteria are interrelated and inseparable.

The need for ecological quality as well as aesthetic quality within the rural landscape is seen as a step forward in cultural development.

To make EU regulations based on planning objectives seems premature at present. A checklist was established based on the criteria mentioned and was formulated in such a way as to compare an organic farm with a conventional farm in the same landscape unit. The checklist was implemented on organic and adjacent conventional farms in nine regions of Europe. In this article a large farm was considered in the Dehesa landscape in Andalusia and small farms were considered in the fringe of Lisboa, in the Netherlands and on Crete.

The two sets of criteria proved able to include all the arguments named during the evaluation of the contribution of organic farms to landscape quality. ©2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Organic farms; Landscape quality; Diversity and coherence

∗Corresponding author. Tel.: +31-(0)-317-423089

E-mail address: [email protected] (J. Kuiper)

1. Introduction

The purpose of this research was to formulate criteria to evaluate and stimulate the contribution of organic farms to sustainable landscape quality.

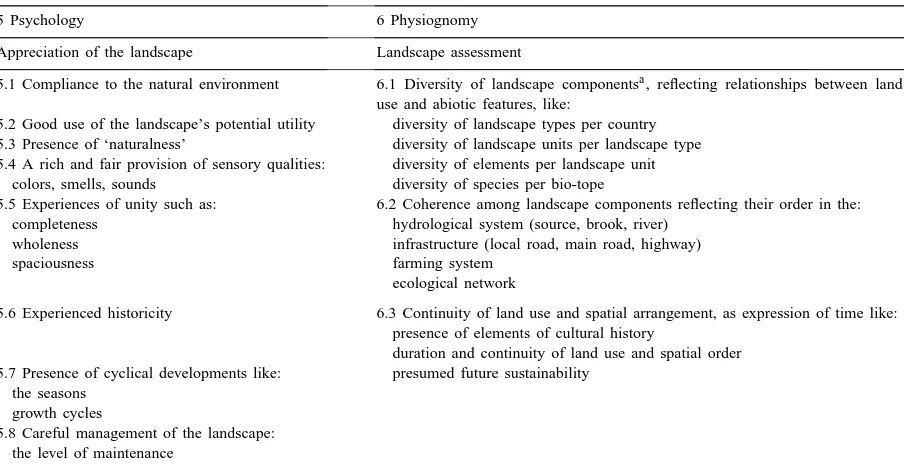

Table 1

Criteria for the quality of the cultural environment

5 Psychology 6 Physiognomy

Appreciation of the landscape Landscape assessment

5.1 Compliance to the natural environment 6.1 Diversity of landscape componentsa, reflecting relationships between land use and abiotic features, like:

5.2 Good use of the landscape’s potential utility diversity of landscape types per country 5.3 Presence of ‘naturalness’ diversity of landscape units per landscape type 5.4 A rich and fair provision of sensory qualities: diversity of elements per landscape unit

colors, smells, sounds diversity of species per bio-tope

5.5 Experiences of unity such as: 6.2 Coherence among landscape components reflecting their order in the: completeness hydrological system (source, brook, river)

wholeness infrastructure (local road, main road, highway)

spaciousness farming system

ecological network

5.6 Experienced historicity 6.3 Continuity of land use and spatial arrangement, as expression of time like: presence of elements of cultural history

duration and continuity of land use and spatial order 5.7 Presence of cyclical developments like: presumed future sustainability

the seasons growth cycles

5.8 Careful management of the landscape: the level of maintenance

aDescription of landscape components: a landscape element consists of homogenous soil features, land use and spatial appearance

(hedge, watercourse, road); a landscape pattern refers to the pattern of one type of elements (road-, planting-, ditch pattern); a landscape unit consist of similar hydrological and soil features, similar land use and a similar spatial arrangement of landscape elements and patterns; a landscape type consists of corresponding geomorphological origin and consists of several landscape units.

An international group of researchers, of differ-ent disciplines, (named Concerted Action) exchanged methods and criteria concerning landscape quality in workshops and checked the criteria by visiting farms in nine European Countries.

During the visits two kinds of criteria appeared, some more subjective and some more objective. There-fore, two sets of validation were proposed, non-expert and expert criteria.

The group saw small farms (4 ha), large farms (270 ha), organic mixed farms and rather specialized farms, farms in rural areas and those on the fringe of expanding cities. The visits to the farms took 2–3 h and were accompanied by the farmer and local experts.

2. Method

The criteria were ordered in a table consisting of six columns. The columns 1 and 2 are related to the abiotic/biotic aspects, the columns 3 and 4 to the

eco-nomic/social aspects and the columns 5 and 6 to the cultural aspects.

This article examines the criteria for the quality of the cultural environment in columns 5 and 6 (Table 1), named landscape quality.

To evaluate the quality of the cultural environment Concerted Action used both non-expert and expert values.

The non-expert values of column 5, derived from psychological principles (Coeterier, 1996), contains criteria for the appreciation of the present local land-scape of the farm by users and inhabitants.

The subgroup of Concerted Action dealing with cul-tural aspects, checked if these criteria were applicable to the visited farms. In this article some examples of the implementation of the criteria are shown and some problems, which appeared.

To evaluate the contribution of organic farms to landscape quality organic and adjacent conventional farms in the same landscape unit were compared.

To formulate general standards for the criteria de-termining the quality of the cultural environment is not without problems, and even impossible in some cases. It is not reasonable to make EU regulations out of these criteria. For example, the need for ‘natural-ness’, for landscapes which reflect a suggestion of be-ing rather natural, not only depends on the landscape of the country at stake, but also on the observer. The ideas about nature of most urban citizens are quite dif-ferent from the ideas of farmers.

A standard for a particular number of smells also does not seem rational. Not everybody by nature or training is able to distinguish the same amount of odors. At most, one standard could be, the avoidance of pervasive bad smells. Aesthetic demands for any length or surface of hedges per area or for a particular amount of trees and woodlots are not adequate for all Dutch or European landscapes. Neither is a standard for diversity. More diversity of landscape elements in each landscape type does not result in more diversity of landscape types (Kuiper, 1997).

So we decided to introduce questions to evaluate the contribution of organic farms to landscape quality. A main question for the non-expert values was whether the landscape of the organic farms could be appreciated more than that of the adjacent conven-tional farms. A main question for the expert values was whether the landscape of the organic farms better express the natural and cultural heritage and present use and meaning than the landscape of the adja-cent conventional landscape. A more concrete item was the evaluation of additional planting on organic farms. This raised the question of whether planting automatically contributes to landscape quality?

3. Criteria for the quality of the cultural environment

The appearance of a landscape is rather vulnerable. Landscapes have many powerful aggressors (farming,

tourism urban development, war) and only a few pow-erless defenders. “But whatever the urban accessories, our longing for the country is real: it is a genuine de-sire for the natural rather than the man-made”. “We want our cities more leafy, our suburbs more coun-trified, our countryside wilder — all our landscapes, in fact, transposed from the man-made towards the natural”. (Fairbrother, 1974). It is not nature which is wanted, but an image of nature, by Coeterier called naturalness.

The landscape has an important influence on the welfare and well-being of people and their ability to survive in a society at large.

The landscape is a physical environment of ob-jective measurable attributes. Apart from physical features, landscape has inter-subjective qualities per-ceived and valued by people. And as cultural and aesthetic values of observers change over time, the images and values of landscapes change over time too (Vos and Fresco, 1994). For the assessment of the cultural environment we propose to use two sets of criteria. The first set of column 5 refers primarily to the appreciation of rural landscape by its users and inhabitants, the so-called non-expert validation. This set is based on criteria derived from landscape psy-chology that systematically identified aspects of the landscape, which its users observe and appreciate or depreciate (Coeterier, 1996).

The second set of criteria refers to expert validation and is mainly derived from physiognomy, geography and landscape architecture (Kuiper, 1998). The expert is presumed to know about the cultural history of each landscape at stake, for instance by using old maps, by reading the features of the surrounding landscape of the farm and by imagining a picture of ‘an ideal landscape’ under the chosen conditions.

3.1. Non-expert values of column 5

to relax, recover, or otherwise be efficiently engaged in professional activities.

The criteria used in column 5 have been developed by Coeterier (1996). Coeterier, through interviewing inhabitants in a research that covered a period of 20 years, collected, made an inventory of and system-ized a wide range of criteria that reflect the public’s landscape appreciation. From sociological research (Volker, 1997), it has become clear that the apprecia-tion is not only important for the public’s well-being, but also for the sustainable management of that land-scape. People are willing to contribute to the man-agement, be it financially or by investing private time and energy, but only insofar as they feel appreciation, pleasure and compassion for that landscape.

Eight main criteria have been distinguished with respect to the appreciation of the landscape (Table 1).

5.1 Compliance to the natural environment The aim here is to emphasize the importance of abiotic features, such as geomorphology, relief, soil and water and show how these are the very foundations of the landscape determining all kinds of land-uses, actions and perceptions.

5.2 Good use of the landscape’s potential utility The aim here is the clear visibility of a legitimate use of all functional aspects of the landscape, accord-ing to society’s demands and the region’s carryaccord-ing capacity.

To achieve an appreciated landscape, Fairbrother (1974) mentions that ‘landscape is essentially the physical expression of land use and it is with (good) land use that we have to begin’.

5.3 Presence of ‘naturalness’

The aim here is to encourage a landscape which evokes the suggestion of being not totally man-made, a landscape in which some of the natural heritage has been respected. At the moment societies’ demands for strong feelings of ‘naturalness’ seem to be greatest in the European countries with the highest external in-put and most intensive agriculture. The presence of non-productive sites, old trees, and dominance of nat-ural lines, patterns and materials over artificial ones are important parameters.

5.4 A rich and fair provision of sensory qualities The aim here is to emphasize the importance of a wide and diverse range of appreciated, recuperative and inspiring sensory qualities and removing those that are known to be intrusive and stress inducing.

5.5 Experiences of unity

The aim here is to emphasize the importance of ex-periencing the landscape as a whole, with all parts fitting together. Unity implies an added value, that none of the single parts possess. Completeness refers to the presence of all the appropriate elements, that usually belong to that landscape. Wholeness is as-sessed through the absence of non-fitting, disturbing elements.

5.6 Experienced historicity

The aim is to respect the cultural heritage and to em-phasize how necessary it is for the landscape to contain elements out of different periods of cultural history.

5.7 Presence of cyclical development

The aim here is to emphasize the importance of the sensory attributes of the change of seasons reflecting the natural order of creation. Other parameters are succession of bio-topes and landscape maintenance cycles.

5.8 Careful management of the landscape

The aim here is a well-kept landscape. The ‘nice and tidy’ approach of modern farms would fit into this criterion, but can indicate over-management. On the other hand, organic farms with more room for natu-ral plants (weeds) and wild animals can fit into this criterion too.

3.2. Expert values of column 6

The three criteria used in column 6 were developed in a long term research project reflecting landscape plans, at different scale levels in the river area of the Netherlands (Kuiper, 1998). A short summary of this research is presented here.

Many landscape-ecology theories have been pub-lished about the best physical features and spatial arrangements for species diversity, for connectivity between ecosystems and for their persistence (Forman and Godron, 1986; Soulé and Simberloff, 1986).

In landscape architecture, the orientation of people in space and time has been considered as an important aspect of the aesthetic landscape quality. It is said to add some feeling of security.

parts clearly interconnected. The observer would be well oriented”.

Vroom (1986) mentioned the need to be able to identify, to explain and to recognize the landscape.

In both disciplines the vertical, horizontal and tem-poral relationships in the landscape have been ana-lyzed for years. Together they cover, what is called, the landscape structure. If a landscape reflects vertical, horizontal and temporal relationships, resulting in di-versity of landscape components, coherence between them and continuity of important components, the ob-server will be able to orientate himself in space and time.

The three criteria, diversity, coherence and continu-ity were used as a common basis for the planning ob-jectives with special regard to aesthetic and ecological quality.

The first hypothesis states that the factors necessary for landscape quality are:

1. A diversity of landscape elements, landscape pat-terns, landscape units and landscape types, which reflect the vertical relationships between land use and abiotic features with regard to the identity of each component; A diversity of ecosystems, habi-tats and species based on the abiotic conditions. 2. A coherence that reflects the spatial relationships

between the landscape components, including their order, in favor of the legibility of the land-scape.

3. A spatial coherence that offers connectivity be-tween similar ecosystems.

4. Continuity of land use of important parts of the landscape in favor of recognisability over time and reflection of cultural history with flexibility of land use in other parts; Continuity of land use and spatial arrangement to enhance the persistence of present and proposed ecosystems.

The second hypothesis states that landscape diver-sity should be the result of several coherences and that spatial coherence should lead to landscape diversity. The dialectic of the criterion diversity, considered at different scale levels (Kuiper, 1997) indicates the need to evaluate the farms not only at farm level, but also at regional and even at national and international level.

The criteria above were used in a former student pilot project to compare organic and adjacent conven-tional farms (Stroeken et al., 1993). Table 2 consists of the theoretical questions in mind which

accompa-nied the later farm visits of Concerted Action (Kuiper, 1994).

One visually important decision made by organic farmers is to encourage planting. Planting is important for many (a)biotic reasons. A careful location of a native planting pattern can improve the aesthetic and ecological quality much more than planting a hedge or some foreign trees on a coincidental location. Some of the planning objectives concerning this aspect, are presented here (Sloet van Oldruitenborgh et al., 1990; Kuiper, 1996, 1997):

1. in favor of landscape diversity, planting should be located on sites offering the greatest scope for biodiversity and where the planting accentuates important landscape elements or patterns (like wa-tercourses, steeper slopes, ditches, roads); 2. in favor of coherence, planting should be located

on sites offering the greatest scope for sustainable connectivity and where the planting reflects the or-der among important landscape elements/patterns (watercourse network, road network);

3. in favor of continuity, planting should be located on sites offering chances for long term natural development of a minimum of a 100 years (f.i. along watercourses, local roads).

Planting along the watercourses of a landscape unit shall not be realized as the sum of coincidental de-cisions at farm level. To implement such a landscape plan, the organic farmers must be willing to adapt their decisions to the plan.

4. Examples of implementation of the criteria in different regions

In this paper the following farm visits are described: 1. Spain, Andalusia, two farms of the Dehesa

Land-scape (1995);

2. The Netherlands, an organic farm (18 ha) and an adjacent conventional farm and an organic goat farm (9 ha) belonging to an estate, (1995); 3. Portugal, small organic horticultural farms (4 ha)

on the fringe of Lisboa (1996); 4. Crete, an organic farm (35 ha), (1997).

The dialectic of the criterion diversity is presented in Section 4.1.

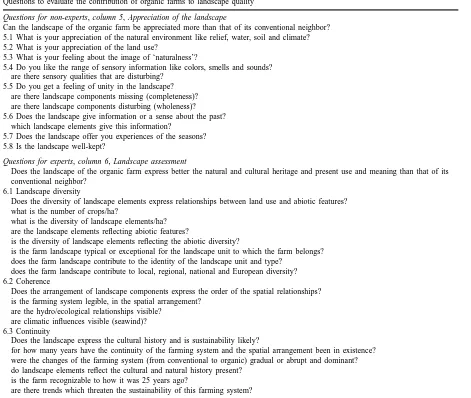

Table 2

Questions to evaluate the contribution of organic farms to landscape quality

Questions for non-experts, column 5, Appreciation of the landscape

Can the landscape of the organic farm be appreciated more than that of its conventional neighbor? 5.1 What is your appreciation of the natural environment like relief, water, soil and climate? 5.2 What is your appreciation of the land use?

5.3 What is your feeling about the image of ‘naturalness’?

5.4 Do you like the range of sensory information like colors, smells and sounds? are there sensory qualities that are disturbing?

5.5 Do you get a feeling of unity in the landscape? are there landscape components missing (completeness)? are there landscape components disturbing (wholeness)? 5.6 Does the landscape give information or a sense about the past?

which landscape elements give this information?

5.7 Does the landscape offer you experiences of the seasons? 5.8 Is the landscape well-kept?

Questions for experts, column 6, Landscape assessment

Does the landscape of the organic farm express better the natural and cultural heritage and present use and meaning than that of its conventional neighbor?

6.1 Landscape diversity

Does the diversity of landscape elements express relationships between land use and abiotic features? what is the number of crops/ha?

what is the diversity of landscape elements/ha? are the landscape elements reflecting abiotic features?

is the diversity of landscape elements reflecting the abiotic diversity?

is the farm landscape typical or exceptional for the landscape unit to which the farm belongs? does the farm landscape contribute to the identity of the landscape unit and type?

does the farm landscape contribute to local, regional, national and European diversity? 6.2 Coherence

Does the arrangement of landscape components express the order of the spatial relationships? is the farming system legible, in the spatial arrangement?

are the hydro/ecological relationships visible? are climatic influences visible (seawind)? 6.3 Continuity

Does the landscape express the cultural history and is sustainability likely?

for how many years have the continuity of the farming system and the spatial arrangement been in existence? were the changes of the farming system (from conventional to organic) gradual or abrupt and dominant? do landscape elements reflect the cultural and natural history present?

is the farm recognizable to how it was 25 years ago?

are there trends which threaten the sustainability of this farming system?

Discussions between two subgroups of Concerted Action about the landscape quality of different ways of managing olive yards and problems with the contri-bution of additional planting to landscape quality, are described in Section 4.4.

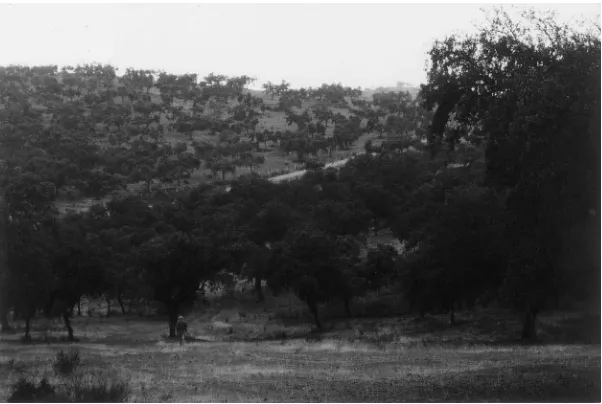

4.1. Implementation of the criteria in Andalusia

In Andalusia a traditional (organic) and a conven-tional farm were visited. They both belonged to the

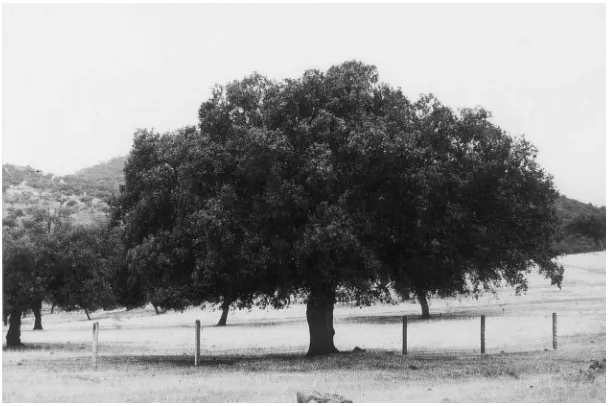

Fig. 1. Dehesa farming system of pruned solitary oaks in Andalusia, Spain.

The landscape of farm (2) is completely deforested and was transformed 75 years ago into large open crop fields without any planting. Over the last few years, it has been intensively grazed by sheep, this practice encouraged by EU subsidy for each sheep farmed.

The visit to these farms was in 1995 and at that time the criteria of the columns 5 and 6 were still mixed.

Many kinds of sensory qualities were perceived on the traditional Dehesa farm. The sparse wood is rich with herb fragrances. Many kinds of bird songs could be heard. The appreciation of the traditional farm was great, its landscape was attractive and inviting, pro-viding sun and shade. The landscape of the traditional farm expressed the natural and cultural heritage very well. The differences in exposition and slope are em-phasized by a diversity of oak species and by differ-ences in the density of the tree planting. Each pruned oak has its own characteristics (Fig. 2).

Negative perceptions appeared in the transformed conventional farm such as feeling exposed to all ex-treme weather conditions. At that moment in May it was bare land without any flowers or animals. On the steepest slopes erosion was visible. There were no landscape elements except a refuge on the top of a hill and little landscape diversity. There was no apprecia-tion at all for this transformed farm. Its landscape did not express the fine abiotic diversity nor the cultural

history. Though the relief of the hills was better visi-ble because of the openness.

It is a remarkable fact that the traditional Dehesa farm contributes to European and National diversity of landscape types, but at the moment not to regional landscape diversity. The original Dehesa landscape is monotonous for the walker or cyclist. It is possi-ble to bike for days in the same, closed landscape without having a panoramic view. The transformed conventional farm with its open landscape does not contribute to European or National diversity of land-scape types, but provides an exceptional panoramic view to the tourists and therefore diversity within the Dehesa landscape, as far as there are still just a few of these open landscapes.

The sustainability of the traditional Dehesa farm-ing system is endangered by changes in society. The living apart, by the farmers, from their families and villages, for a great part of the year has become less accepted.

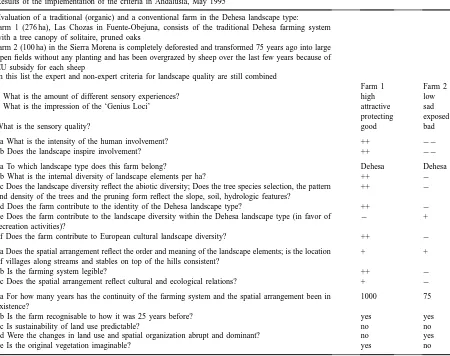

Table 3

Results of the implementation of the criteria in Andalusia, May 1995

Evaluation of a traditional (organic) and a conventional farm in the Dehesa landscape type: farm 1 (276 ha), Las Chozas in Fuente-Obejuna, consists of the traditional Dehesa farming system with a tree canopy of solitaire, pruned oaks

farm 2 (100 ha) in the Sierra Morena is completely deforested and transformed 75 years ago into large open fields without any planting and has been overgrazed by sheep over the last few years because of EU subsidy for each sheep

In this list the expert and non-expert criteria for landscape quality are still combined

Farm 1 Farm 2

1 What is the amount of different sensory experiences? high low

2 What is the impression of the ‘Genius Loci’ attractive sad

protecting exposed

What is the sensory quality? good bad

3a What is the intensity of the human involvement? ++ −−

3b Does the landscape inspire involvement? ++ −−

4a To which landscape type does this farm belong? Dehesa Dehesa

4b What is the internal diversity of landscape elements per ha? ++ −

4c Does the landscape diversity reflect the abiotic diversity; Does the tree species selection, the pattern and density of the trees and the pruning form reflect the slope, soil, hydrologic features?

++ −

4d Does the farm contribute to the identity of the Dehesa landscape type? ++ −

4e Does the farm contribute to the landscape diversity within the Dehesa landscape type (in favor of recreation activities)?

− +

4f Does the farm contribute to European cultural landscape diversity? ++ −

5a Does the spatial arrangement reflect the order and meaning of the landscape elements; is the location of villages along streams and stables on top of the hills consistent?

+ +

5b Is the farming system legible? ++ −

5c Does the spatial arrangement reflect cultural and ecological relations? + −

6a For how many years has the continuity of the farming system and the spatial arrangement been in existence?

1000 75

6b Is the farm recognisable to how it was 25 years before? yes yes

6c Is sustainability of land use predictable? no no

6d Were the changes in land use and spatial organization abrupt and dominant? no yes

6e Is the original vegetation imaginable? yes no

for agriculture. The planting should emphasize these sites and improve the ecological quality.

4.2. Implementation in the Netherlands

The evaluation was made for (1) an organic and a conventional farm on a transition zone from dune to polder landscape and for (2) an organic farm belonging to an estate on the fringe of a town.

4.2.1. The organic mixed farm of 18 ha ‘Noorderhoeve’ near Schoorl and its adjacent conventional farm

These farms are situated on the transition zone from dune to polder landscape and consist of a great

va-riety of abiotic features. From old maps it is known that these transition zones consist of the most fine grained diversity of landscape elements. In the Nether-lands these transition zones were known for the rich-ness of species. On the organic farm a greater diversity of land use and of landscape elements (linear plant-ing elements, hedges and many ditches) was found compared to the conventional farm. Also, there was a strong relationship between land use and abiotic fea-tures (Stroeken, 1994). The spatial arrangement on the organic farm consisted of spaces of different kinds and size. The fine grained landscape of the organic farm reflected well the abiotic variety of this transition zone and of the integrated farming system.

Fig. 2. One of the solitary oaks of the Dehesa landscape.

fields. This expressed well the conventional farming system but did not express the fine abiotic variety.

Organic mixed farms, situated in such a fine grained transition zone, have a greater chance to contribute more to landscape diversity than conventional farms.

4.2.2. The organic goat farm ‘Capricas’ (9 ha) near Ede

This farm is a part of an estate on the fringe of the town Ede. The checklist was difficult to answer. “On the Capricas farm, seasonal aspects and ecologi-cal quality are not very pronounced” (Hendriks et al., 1997). The goat farm consisted of open fields. It is surrounded by woods, which belongs to the estate. It is difficult to say in this research whether for instance birds are present because of the surrounding woods, because this is an open space in the woods or because this is an organic goat farm. On the other hand, ‘the farm complies very well to the objectives set for the development of the estate’. This farm is too small to be distinguishable from the features of the estate and from adjacent conventional farms. The characteristics of the estate dominated those of the particular farm.

In small organic farms in the Netherlands for in-stance questions about sensory qualities were difficult to answer. To perceive fine odors can be difficult due to the smell of the bio-industry of the adjacent farms.

4.3. Implementation in Portugal

The evaluation of the small organic horticultural farms (4 ha) suffered the same problems as already mentioned. In addition the sustainability of these farms on the fringe of the expanding city Lisboa is doubt-ful. Only a very strong government and cooperation of several organic farmers will be able to achieve sus-tainable landscape quality. The attention to the hydro-logical system and the restoration of old stone wells was positive.

4.4. Implementation on Crete

On Crete the hills mainly consist of old high stem olive groves and the plains of young low stem olive groves. The farms are in the villages. On the top of the hills there are shelters for the laborers (Tables 4 and 5).

The checklist was made for an organic olive farm of 35 ha around the top of a hill.

Table 4

Results of the implementation of the non-expert criteria on Crete

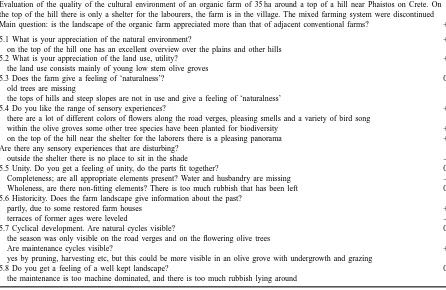

Evaluation of the quality of the cultural environment of an organic farm of 35 ha around a top of a hill near Phaistos on Crete. On the top of the hill there is only a shelter for the labourers, the farm is in the village. The mixed farming system were discontinued Main question: is the landscape of the organic farm appreciated more than that of adjacent conventional farms? +

5.1 What is your appreciation of the natural environment? ++

on the top of the hill one has an excellent overview over the plains and other hills

5.2 What is your appreciation of the land use, utility? +

the land use consists mainly of young low stem olive groves

5.3 Does the farm give a feeling of ‘naturalness’? 0

old trees are missing

the tops of hills and steep slopes are not in use and give a feeling of ‘naturalness’

5.4 Do you like the range of sensory experiences? ++

there are a lot of different colors of flowers along the road verges, pleasing smells and a variety of bird song

within the olive groves some other tree species have been planted for biodiversity + on the top of the hill near the shelter for the laborers there is a pleasing panorama ++ Are there any sensory experiences that are disturbing?

outside the shelter there is no place to sit in the shade −

5.5 Unity. Do you get a feeling of unity, do the parts fit together? 0

Completeness; are all appropriate elements present? Water and husbandry are missing −

Wholeness, are there non-fitting elements? There is too much rubbish that has been left 0 5.6 Historicity. Does the farm landscape give information about the past?

partly, due to some restored farm houses +

terraces of former ages were leveled −

5.7 Cyclical development. Are natural cycles visible? 0

the season was only visible on the road verges and on the flowering olive trees

Are maintenance cycles visible? +

yes by pruning, harvesting etc, but this could be more visible in an olive grove with undergrowth and grazing

5.8 Do you get a feeling of a well kept landscape? 0

the maintenance is too machine dominated, and there is too much rubbish lying around

The appreciation of the farm scored rather well also because of the excellent situation around the top of a hill.

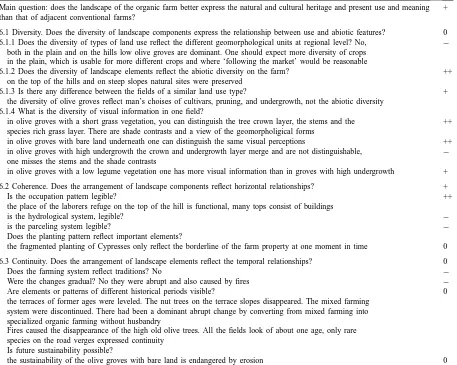

In the olive yards on Crete different kinds of man-agement were distinguished:

1. a short grass vegetation by grazing under the (high stem) olive trees;

2. bare land by ploughing under high and low stem olive trees (Fig. 3);

3. a high spontaneous herb vegetation of different species under the trees (Fig. 4);

4. seeded clovers between the rows of olive trees. These different kinds of management effect erosion, species richness, social life and visual experiences. The different olive yards (Olea Europea varieties) lead to discussions between two subgroups of Concerted Action, because the aesthetic quality of management types (2), (3) and (4) did not coincide with the (a)biotic quality.

The old high stem olive yards (1) with grazing un-derneath are protected against erosion and consist of the most healthy and fertile soil in comparison to the other kinds of management. They also consist of the most species and the most coherent diversity of visual perceptions. Aesthetic and ecological quality are both high.

Table 5

Results of the implementation of the expert criteria on Crete

Main question: does the landscape of the organic farm better express the natural and cultural heritage and present use and meaning than that of adjacent conventional farms?

+

6.1 Diversity. Does the diversity of landscape components express the relationship between use and abiotic features? 0 6.1.1 Does the diversity of types of land use reflect the different geomorphological units at regional level? No, −

both in the plain and on the hills low olive groves are dominant. One should expect more diversity of crops in the plain, which is usable for more different crops and where ‘following the market’ would be reasonable

6.1.2 Does the diversity of landscape elements reflect the abiotic diversity on the farm? ++ on the top of the hills and on steep slopes natural sites were preserved

6.1.3 Is there any difference between the fields of a similar land use type? + the diversity of olive groves reflect man’s choises of cultivars, pruning, and undergrowth, not the abiotic diversity

6.1.4 What is the diversity of visual information in one field?

in olive groves with a short grass vegetation, you can distinguish the tree crown layer, the stems and the ++ species rich grass layer. There are shade contrasts and a view of the geomorpholigical forms

in olive groves with bare land underneath one can distinguish the same visual perceptions ++ in olive groves with high undergrowth the crown and undergrowth layer merge and are not distinguishable, −

one misses the stems and the shade contrasts

in olive groves with a low legume vegetation one has more visual information than in groves with high undergrowth +

6.2 Coherence. Does the arrangement of landscape components reflect horizontal relationships? +

Is the occupation pattern legible? ++

the place of the laborers refuge on the top of the hill is functional, many tops consist of buildings

is the hydrological system, legible? −

is the parceling system legible? −

Does the planting pattern reflect important elements?

the fragmented planting of Cypresses only reflect the borderline of the farm property at one moment in time 0

6.3 Continuity. Does the arrangement of landscape elements reflect the temporal relationships? 0

Does the farming system reflect traditions? No −

Were the changes gradual? No they were abrupt and also caused by fires −

Are elements or patterns of different historical periods visible? 0

the terraces of former ages were leveled. The nut trees on the terrace slopes disappeared. The mixed farming system were discontinued. There had been a dominant abrupt change by converting from mixed farming into specialized organic farming without husbandry

Fires caused the disappearance of the high old olive trees. All the fields look of about one age, only rare species on the road verges expressed continuity

Is future sustainability possible?

the sustainability of the olive groves with bare land is endangered by erosion 0

abiotic and biotic aspects preferred any undergrowth above bare land.

Like the conventional farmers also the organic farm-ers had olive yards in the plains, probably due to subsidies.

Olive yards (3) and (4) are in majority on the organic farms of Crete. In the low stem olive yards goat and sheep would damage the trees. The traditional way of combining high stem olive trees and husbandry, which have the best effects for the criteria of the abiotic, biotic and cultural environment, tends to vanish. This is because of changes in society. The farmers are very content not to have to care continuously for grazing animals anymore. Their social life is improved.

The organic farmer added other tree species on this farm to improve diversity. The question rises whether the added planting contributes to sustainable landscape quality.

Fig. 3. Olive yard on Crete with bare underground and added Cypressus planting.

Fig. 4. Olive yard on Crete with herb vegetation and added Cypressus planting.

to sustainable landscape quality. It did not reflect an important landscape element. A planting aligning an important landscape element like an old local road, a crest, or a brook will have more chance to improve durable aesthetic and ecological qualities than an in-discriminate planting.

The organic farmer also added some scattered fruit trees between the olive yards. The fruit trees add, lo-cally, colors and smells, but do not result in a

distinc-tive landscape element that contributes to aesthetic or ecological quality.

5. Evaluation of landscape quality

This is because it is not rational to demand a certain amount of diversity of landscape elements or smells all over Europe. The organic farm is evaluated in comparison to an adjacent conventional farm in the same landscape unit.

5.1. Evaluation of the organic farms by the criteria for non-experts

The visited organic farms evoke the feeling of ‘nat-uralness’ better than the adjacent conventional farms. More sensory qualities such as flower perfumes and bird songs were experienced. The seasons were also more obvious on the organic farms, for instance by added planting or fruit trees.

On the organic farms often ‘neglected’ corners or fields were visible, as if the conversion, the sometimes hostile conventional neighbors and the surplus of work on the farm seemed to cost too much energy.

On the traditional farm in the Dehesa landscape of Andalusia, the visitors felt protected against extreme weather influences, inspired to be involved and com-fortable. On the adjacent modern farm, the visitors felt exposed, sad and uncomfortable.

On the visited organic farms in the Netherlands and Portugal more attention was paid to the component water, for instance by restoring ditches and old wells, than on the adjacent conventional farms.

On the organic olive yards on Crete, old trees and husbandry were missing in the landscape and rubbish was found. The feeling of historicity was evoked by the restoration of the old farmhouses.

5.2. Evaluation of the organic farms by the criteria for experts

On the visited organic farms there was more diver-sity of crops, of different treatments of the same crop and more diversity of species within one field. This increased diversity was more often due to the farm-ers initiative (on Crete, Toscany) and sometimes the result of adaptation to abiotic features (Cordoba, the Netherlands). On the visited organic farms there was more biodiversity than on adjacent farms because of added linear planting elements, or natural vegetation. The visited organic farms succeeded so far quite well in improving the ecological quality considered on farm level.

However on Crete, the ‘natural’ elements, plant-ing or field margins did not seem to fit into a re-gional ecological network. Kabourakis (1996) wrote that “present ecological agriculture has no explicit guidelines and technology for landscape and nature. In ecological farming systems biodiversity is to be in-creased especially by an ecological infrastructure”.

The use of both the hills and the plains for olive yards does not reflect the difference of abiotic potentials.

The visited organic farmers seemed to pay less at-tention to the demanded aesthetic qualities. New plant-ing which could contribute to the orientation in space and to the identity of the landscape unit was rare. On the most farms the added planting did not relate to im-portant landscape elements. The hydrological system, for instance, was not very legible.

In the organic olive yards with a high herb layer under the low stem trees, there was less diversity of contrasting perceptions than in the yards with short grass or bare land. It is unlikely that olive yards with a high herb layer under the low stem trees become a source of inspiration for artists and photographers.

The contribution of the farms to the orientation in time was visible in the restoration of old farm houses. The former terraces of Crete and Toscany however were leveled. This may well have happened before the conversion into organic farming.

6. Discussion

The question arises as to what the EU can ask from the organic farmers in exchange for the subsidy? Can the EU ask farmers to adapt their farming decisions to regional planning objectives in order of landscape quality? Can the EU ask from farmers in Andalusia to go on living apart from their families or from the olive farmers on Crete to reintroduce husbandry?

7. Conclusions

Not every question is answerable on each organic farm. For instance, small organic farms are difficult to distinguish from their environment like the goat farm of 9 ha in the Netherlands and the horticultural farms of 4 ha in Portugal.

It may be possible to stimulate organic farming by subsidizing each starting farm, including the smallest ones. But for a long term perspective a minimal size, for instance realized by a cooperation of neighboring organic farms, will be necessary for a structural con-tribution to landscape quality. In summary, it is clear that the questions are not suitable for small farms and it is debatable whether small organic farms can con-tribute to sustainable landscape quality.

Acknowledgements

The following members of the Concerted Action worked on the implementation of the criteria for the cultural environment: M. Beismann, A. Bosshard, M. Clemetsen, M. Colquhoun, A. Firmino, G. Fry, C. Hojring, K. Hendriksen, M. Hurter, J. Kuiper, R. Rossi, D.J. Stobbelaar, F. Stroeken. In addition many local people contributed to the implementations.

References

Coeterier, J.F., 1996. Dominant attributes in the perception and evaluation of the Dutch landscape. Landscape and Urban Planning 34, 27–44.

Fairbrother, N., 1974. The nature of landscape design. Architectural Press, London.

Forman, R.T.T., Godron, Michel, 1986. Landscape Ecology. Wiley and Sons, New York, Chichester.

Hendriks, K., Stobbelaar, D.J., van Mansvelt, J.D., 1997. Some criteria for landscape quality applied on an organic goat farm in Gelderland, the Netherlands. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 63, 185–200.

Kabourakis, E., 1996. Prototyping and dissemination of ecological olive production systems. A methodology for designing and a first step towards validation and dissemination of prototype ecological olive production systems (EOPS) in Crete. Thesis Wageningen Agricultural University.

Kuiper, J., 1994. Two strategies of landscape planning in a stream valley. In: Stobbelaar, D.J., van Mansvelt, J.D. (Eds.), Proceedings of the first plenary meeting of the EU-concerted action. Department of Ecological Agriculture, Agricultural University, Wageningen, pp. 101–112.

Kuiper, Juliëtte, 1996. Criteria in order to evaluate the contribution of organic farming to the cultural environment of european

landscapes. In: De Graaff, Jaqueline (1996). Proceedings of the third plenary meeting of the EU-concerted action: The landscape and nature production capacity of organic/sustainable types of agriculture, no. AIR3-CT93-1201. Department of Ecological Agriculture, Agricultural University, Wageningen, pp. 175–189. Kuiper, J., 1997. Organic mixed farms in the landscape of a brookvalley. How can a co-operative of organic mixed farms contribute to ecological and aesthetic qualities of a landscape. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 63, 121–132. Kuiper, J., 1998. Landscape quality based upon diversity, coherence

and continuity: landscape planning at different planning-levels in the river area of the Netherlands. Landscape and Urban planning 43 (1–3).

Kuiper, J., J.D. van Mansvelt, 1999. Critria for the humanity realm: psychology and physiognomy/cultural geography. In: van Mansvelt, J.D., van der Lubbe, M.J. (Eds.), Checklist for Sustainable Landscape Management. Final report of the Concerted Action AIR3 CT93-1210. The Landscape and Nature Production Capacity of Organic/Sustainable Types of Agriculture. Granted by the European Commission, DG VI Department of Rural Development. Elsevier, Amsterdam, New York, pp. 116–134.

Lynch Kevin, 1960. The image of the city. The M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Santos, A. Pérez, Remmers, G.G.A., 1997. A landscape in transition: an historical perspective on a Spanish latifundist Farm. Agriculture Ecosystems and Environment 63, 91–105. Sloet van Oldruitenborgh, C.J.M., Kuiper, J., Santema, R., 1990.

Countryseats in a brook-valley system. In: Cultural aspects of landscape. Proceedings of the IALE conference organised by the working group Culture and Landscape June 1989, PUDOC, Wageningen, pp. 155–166.

Soulé, Michael E., Simberloff, Daniel, 1986. What do genetics and ecology tell us about the design of nature reserves?. Biological Conservation 35, 19–40.

Stroeken, Frank, Hendriks, Karina, Kuiper, Juliëtte, van Mansvelt, Jan Diek, 1993. Verschil in verschijning. Een vergelijking van vier biologische en aangrenzende gangbare landbouwbedrijven. Landschap, Wageningen, 1993/2, pp. 33–45.

Stroeken, Frank, 1994. Differences in appearances. A comparative observation study into organic and conventional farms. In: Stobbelaar, Derk Jan, Jan Diek van Mansvelt (Eds.), Proceedings of the first plenary meeting of the EU-Concerted Action The landcape and nature production capacity of organic/sustainable types of agriculture, Wageningen, pp. 143–151.

Volker, K., 1997. Local commitment for sustainable rural landscape development. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 63, 107– 121.

Vos, W., Fresco, L.O., 1994. Can agricultural practices contribute to functional landscapes in Europe? In: Stobbelaar, D.J., von Manovelt, J.D. (Eds.), Proceedings of the First plenary meeting of the Eu-concerted actionDepartment of Ecological Agriculture, Agricultural University, Wageningen.