ANALYSIS

Evolution of economy and environment: an application to

land use in lowland Vietnam

W. Neil Adger *

School of En6ironmental Sciences and Centre for Social and Economic Research on the Global En6ironment, Uni6ersity of East Anglia,Norwich,NR4 7TJ,UK

Received 2 September 1998; received in revised form 17 December 1998; accepted 12 March 1999

Abstract

This paper analyses the interactions between land use, institutions and culture in the context of climatic extremes in Vietnam. Although there has been a long history of examining the evolutionary nature of markets and institutions within an institutional economics framework, developing the institutional economic approach to include society environment interactions allows examination of processes which facilitate and constrain economic development. For example, this approach is used here to explain adaptation processes whereby climatic risk affects collective responses. These responses form an evolutionary link between institutions, culture, resources and the physical environment. The paper argues that historically climatic risks have been a factor in technological and political response within the agrarian society of Vietnam, in the sense that climatic extremes have acted as triggers to some significant social upheavals. In the past century, the impacts of colonialism, political change and related changes in social organisation, have significantly altered the social basis of resilience to climate extremes. © 1999 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Coevolution; Agricultural development; Climate change; Vietnam

www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon

1. Introduction

This paper develops two themes. Firstly, the interaction of society and environment relations is expounded as an evolutionary process whereby both society and the physical environment deter-mine the structure of market institutions. The

analysis describes economic development as a process whereby the selection of activities by insti-tutions operates within available niches. The key institutions and manifestations of such evolution are those surrounding property and access to resources. This theme is developed with reference to the evolution of land use under diverse histori-cal social and politihistori-cal circumstances in the his-tory of Vietnam. Utilisation of natural resources in Vietnam has fundamentally been affected by * Tel.: +44-1603-593732; fax:+44-1603-250588.

E-mail address:[email protected] (W.N. Adger)

the pre-colonial, colonial, communist, and post-communist institutions and technologies of land use. Understanding of present day vulnerability and adaptation to environmental change requires historical analysis of the land use and social or-ganisation of the agrarian economy.

A second theme of this paper is that of the role of climate as an environmental resource within an evolutionary framework. In debates on environ-ment and society interactions, climate has vari-ously been portrayed as one constraint on the ability of regions and societies to undertake eco-nomic development (Sachs, 1997), or as a key factor in agricultural development, in particular in pre-industrial societies (de Vries, 1980). This pa-per by contrast argues that climate acts as one element in the portfolio of risk inherent in utilis-ing natural resources, and that coevolution occurs such that land use alters in response to risks from extreme events rather than coevolving directly with the climate system. This theme is illustrated with reference to the Vietnamese lowland societies of the past millennium.

The paper proceeds by outlining the theoretical foundations of coevolutionary analysis from the perspective of institutional economics. It demon-strates that economics has had a long history of examining economic systems in an evolutionary context, concentrating on how institutions them-selves evolve and determine the structure of economies in terms of organisation, markets and scale. Bringing the physical resource base into the calculus leads to the observation that not only does the economic system evolve but that it has a direct relationship with the natural system on which it depends. Treating climate as a distinct resource endowment leads to the examination of the evolution of climate risk with economic sys-tems (following Schneider and Londer, 1984; for example). It is argued in this paper that the important interactions between land use, institu-tions and climate are essentially manifest in adap-tation to climate variability, and to extreme climate events in particular. In other words, the economic and climate systems interact with each other in the evolution of social and environmental risks.

This is not to deny the role of climate charac-teristics as one environmental constraint and parameter of land use and cultural evolution. In the context of the wet-rice growing areas of Asia, Bray (1986) demonstrates that the present land allocation, technology and social relations are not ‘matters of chance.’ Rather the development of irrigation and of the social organisation for labour intensive cultivation are key to the eco-nomic structure of these societies. This paper em-phasises the variability and the impact of climate extremes as central issues in this evolution. Insti-tutional strategies and technologies of adaptation, such as investment in irrigation, alter the risk profile from climatic hazards. The feedbacks to climatic risk come about through smoothing the impact of climate variability, for example through irrigation in agriculture, and through protective measures to minimise the impacts of extreme cli-mate events. Thus, in this analytical approach, it is the set of climate risks and their perceptions which coevolve with social forces.

2. The environment in evolutionary economics

2.1. Technological and en6ironmental change

The perspective that economic systems share characteristics of evolutionary biological systems is in large part held by a body of institutional economists.1 This perspective broadly rejects the exclusive focus of neo-classical economic analysis on markets as the sole explanatory variable in the allocation of resources. Institutional economists provide alternative analysis of technologies, insti-tutions, norms and cultures, and power relation-ships to explain the structure and operation of markets. The essential features of institutional economics are:

the focus on social and economic evolution, hence taking an activist orientation towards social institutions;

1Reviews of these approaches can be found in Norgaard

the importance of markets as systems of social control and the importance of collective action and policy intervention in markets;

the importance of technology as a major force in the transformation of economic systems; institutions as the ultimate determinants of

mar-ket structure and allocation of resources; and the belief that values are ensconced in

institu-tions, rather than being solely artifacts of mar-kets or individual preferences (Samuels, 1995).

Only part of the wide-ranging agenda of institu-tional economics focuses on the evolutionary anal-ogy. The study of technological change is the focus of evolutionary theories, though not all institu-tional economics encapsulates these notions. In the words of Samuels, ‘‘it is human activity mediated through technology that determines what is a resource, its relative scarcity and its efficiency’’ (Samuels, 1995, p. 573). Thus the evolutionary concept in economics is principally focused on technological change as the mechanism by which markets, institutions and economies evolve.2 Un-der an institutional economics approach, technical change, as one of the major driving forces of the economic system, creates its own demand rather than being a passive adjustment towards a new equilibrium, responding to exogenous environmen-tal or other factors. A compromise between neo-classical and institutionalist positions would postulate that the evolutionary process can be seen as the dynamic component of the economy, where neo-classical equilibria best explain the present static situation: ‘‘it has been argued [by economists] (albeit never demonstrated) that evo-lutionary processes of adaptation and selection lead precisely to those equilibria analysed by neo-classical economists’’ (Clark and Juma, 1988, p. 209).

The institutional approach to technical change, rejects the exclusive focus of neo-classical econom-ics on prices and markets. Some of these same limits to neo-classical economics are also part of

the agenda of ecological economics. The ecological economic approach points to the biophysical limits of resource use; the high levels of uncertainty concerning the use of biotic ‘natural capital’; and the natural system feedbacks into the economic system (see, e.g. Daly, 1992). Thus the role of biological resources, and implicitly their resilience, within economic systems demonstrates the reso-nance of parts of the ecological economics paradigm with the study of the evolution of economies.

The role of biological evolution in its coevolu-tion with social and economic systems is demon-strated most strikingly with reference to agriculture, the single most significant intervention in the terrestrial environment. Humans fundamen-tally alter the natural selection processes in species utilised for agriculture, and indeed the whole of agricultural development can be conceptualised as the responses and feedbacks of the biotic world to human intervention. But the evolutionary pro-cesses are equally as relevant to the social sphere. The distribution of land holdings in agricultural societies, for example, is determined by a number of factors. These include the past mean size as an historical legacy, farm profitability, the prior adap-tation of new technologies, and the physical parameters of climate, soil and topography (Allan-son et al., 1995). The reproductive activities of individual farms and farm level decision-making within the economic and physical environment therefore determine evolving farm structure and hence the distribution of wealth within a rural economy. Further, technological adoption and its diffusion within the sector is a key element which also evolves with individual decisions deterring or facilitating the spread of these technologies (Nel-son and Winter, 1982; Nel(Nel-son, 1994). Bray (1986) demonstrates the diversity of institutions and fac-tors which constitute ‘paths of technical develop-ment’ in agriculture. These range from state clearing or provision of land, through to labour saving technology development in times of labour scarcity; and increased production to feed rapidly expanding population. Bray (1986) argues that the paths of technological development taken are ‘‘closely related to the conditions of production specific to the region’’ (p. 198) contrasting Asia and Europe in this context.

2The popularity of evolutionary metaphors for markets and

2.2. Climate and social e6olution

How then does the climate system, and its role in the evolution of economic activity and institu-tions, constitute a condition of production in the evolutionary context? Climate and weather vari-ability are both constraining factors in human interventions with the biotic world. There is a long history of analysis of the adaptation of hu-man societies to different climates and to changes in climates (Lamb, 1995, for example). At the global scale, an analogy of global warming as a coevolutionary process has been set out by Schneider and Londer (1984) and Alexander et al. (1997). They argue that the whole of human society is coevolving with the global climate sys-tem by altering the composition of the atmo-sphere and hence the global climate. The impacts of change in the global climate system result in human society being forced to adapt and to be-come increasingly active in management of re-sources under such changes. The climate system is therefore argued to be coevolving with the global human system in a manner which has potentially significant impacts on risk of irreversible change on the whole planetary system. But the interaction of climate risk can also be observed at smaller scale such that land use systems and institutions have feedbacks with risk and climatic hazards.

The primary factor limiting the analysis of cli-mate and its coevolution with social and eco-nomic systems are the definition of causality and feedbacks (Anderson, 1981). The most important aspects of the causal relationship are the scale of analysis and the directness or remoteness of the links between climate and human connected activ-ities. In terms of temporal scale, Ingram et al. (1981) argue that the inevitable concentration on acute periods of crisis and climate hazards may be misleading. Short-term influences of climate, at the annual or intra-annual scale, do not necessar-ily imply any long-term causal relationship be-tween climate and human history. Where causal direct relationships cannot be inferred from quan-titative data, historical human climate interactions can only be developed through descriptive and conceptual analysis relying on case studies and incorporation of other influences.

This paper argues that the various elements of the social and natural systems (resource endow-ments, land use technologies, and institutions as-sociated with land use) interact with each other in complex ways (Ruttan, 1988). Some of the inter-actions between institutional change, resource use and climate risks are manifested in physical changes, which are monitorable and quantifiable. Others are, by contrast, more difficult to quantify and rely on interpretation and processes such as social learning. Technological improvements can, for example, be quantified in terms of input-out-put ratios, yield increases or returns to invest-ment. Institutional changes are more difficult to quantify, though some institutional researchers have derived indices or proxies, most applicable to formal institutions (e.g. O’Riordan and Jordan, 1999).

Different theoretical perspectives on society-en-vironment interactions usually privileges either the social institution or physical environment, in explaining evolutionary change. For example, Marxist scholars have argued that irrigation tech-nology used in wet rice cultivation in East Asia determines political organisation. Such a conclu-sion thereby de-emphasises the role of population change or land suitability on income and popula-tion growth within agricultural economies. Alter-native institutional approaches examine the transactions costs associated with decision-mak-ing under different property rights regimes. Trans-actions cost approaches quantify some of the institutional linkages through the relative costs of maintaining institutions and the changing relative factor input costs resulting from changes in prop-erty rights. In examining environmental risks, evolutionary approaches attempt to avoid this dichotomy by emphasising the feedbacks between the systems rather than assigning predominance to any single factor.

indicates that the shared communist ideology of peasant farmers in China ‘‘inspired the mobilisa-tion of communal resources to build irrigamobilisa-tion systems and other forms of capital’’ (Ruttan, 1988, p. 250). Thus, it is argued, cultural endowments can reduce the costs of institutional change where these encourage common purpose or collective action.

It seems clear that cultural influences are impor-tant in explaining the interactions between institu-tions, land use and technologies. However, analysis of cultural influences requires case-specific analy-ses, not easily lending themselves to disentangle-ment from the institutional and political factors. As Adams (1986) has commented:

‘‘The flexibilities and potentials inherent in the conjunction of individual action and a cul-tural setting are immense. They become almost overwhelmingly so when epidemic changes are introduced from external sources, as was the case in South and Southeast Asia in colonial times. Extensive cultural intrusions in combina-tion with political dominacombina-tion augment prob-lems of survival just as they may sometimes provide opportunities for economic, political and social advancement’’ (Adams, 1986; p. 279).

Extending an approach to examining institu-tions, culture and land use such that it incorporates feedbacks from natural systems into this set of interactions, adds further complexity. Climatic risks influence both institutional and cultural set-tings, and the appropriate technologies and pro-ductivity of the resource endowments in agriculture. Some of the relationships between climate and other factors are amenable to quantifi-cation and analysis, particularly those associated with the land resources and with technologies.

3. Applying evolutionary analysis: history, institutions and culture in Vietnam

3.1. Lowland‘traditional’ Vietnam

Following the preceding discussions of the cen-tral role of institutions in the evolution of economic

systems, and the potential for incorporating an evolutionary view into the interactions between these economic systems and the natural environ-ment, this section examines the historical evolution of land use and institutions in Vietnam. As already alluded to, there have been many studies of the individual interactions between institutions and technologies, and between the adaptation of new technology as related to underlying resource en-dowments (e.g. Bray, 1986). This section outlines the major historical evolution of technologies and institutions which have governed them over the past millennium in Vietnam. The role of cultural endowments within this analysis is discussed, and the role of climate resources, and their associ-ation with vulnerability to climate change is exam-ined.

This account focuses predominantly on this lowland rice-growing cultural context. Jamieson (1993) argues that lowland society represents the dominant cultural form of Vietnam. Seventy-five percent of the population live in this area, the ethnic groups which came to be known as Vietnamese first settled in the foothills and valleys of the Red River Delta where they first began to reclaim land in the delta itself. This lowland Vietnamese area was largely restricted to the Red River Delta in the north of present-day Vietnam and the central coastal plains. There is therefore differentiation between the lowland regions: they are usually delineated as north, central and south as reflected in the influence of both Chinese and French colo-nial forces. In addition, it is argued that the physical environments of the northern and southern deltas play a role in the dominant culture (Rambo, 1973; Jamieson, 1993). Jamieson (1993) argues that the topography and the substantial land reclamation in the Red River Delta over the centuries has led to it being one of the most unsafe regions of the world, compared to the more benign Mekong Delta:

It is therefore difficult to characterise the insti-tutional and historical realms of Vietnam as ho-mogenous, but rather a series of regions with distinct character. This regionalism is manifest in present day tensions between the centralised sys-tem of government and regional autarky, as well as in distinct regional development problems and agendas (e.g. Rambo et al., 1995; on highland issues).

The account of Vietnamese land use history presented here demonstrates the evolution of rural livelihoods associated with rice production and lowland agriculture, and how these have been periodically subjected to stress and shocks. These stresses and shocks are as frequently caused by political upheaval and civil strife as well as by climatic extremes. The topography of the coastal plains and deltas, and the hierarchical social institutions of the populations across the regions, enabled a sophisticated system of water resource management and intensive agriculture to evolve to minimise the risks associated with cli-matic variability. Superimposed on this system as it evolved over the centuries, however, were peri-odic upheavals associated with invasion and colonisation. At particular points in time the con-vergence of climatic extremes and conflict over property rights punctuated the apparent social and political equilibrium through significant up-heavals.

3.2. Colonialism and its impacts on Vietnam

The major periods in the history of Vietnam which can be identified for the purposes of this paper, are the period prior to European colonisa-tion after the coming into existence of Vietnam as a nation; the French colonial period from around 1859 to 1954; the communist period which include the wars of independence; and the most recent period of economic liberalisation, including the market reforms known as Doi Moi from around the mid 1980s. These periods are not discrete, particularly since they refer principally to eras of political rule. The object of this paper is not to examine political systems, but rather the interac-tions of the implicit property rights with land use and institutions at other scales.

A chronology of the major political events which define these sub-periods is presented in Table 1, with more detailed information on the most recent reform process outlined in Table 2. Within the dominant culture of lowland Vietnam, particularly in the more densely populated north of the country, social structure has been relatively stable and homogenous over the centuries. Village level organisation and systems of land tenure were similar across the lowland regions in the period prior to European interference. The village level organisation was a complex mixture of patriarchy and kinship with Confucian elements, which dom-inated the allocation of communal lands. In addi-tion there was a strong system of government at regional and even national level (see Wiegersma, 1988). Thus, rather than being strictly feudal, the system of political control under both Chinese colonial rule and under independence could be characterised as having some signs of ‘private’ ownership with the basic unit of production being the independent village commune, and hav-ing a centralised monarchy (Nguyen The Anh, 1995).

As indicated in Table 1, the latter part of this period was characterised by national rule by a mandarinate, sometimes as part of Chinese colonial rule and at other times partially or exclu-sively independent. In this period the Emperor would be regarded as the protector of the nation and would perform symbolic duties such as ploughing the first furrow each year for a new rice crop, thereby sealing the link between the state’s position as responsible for national welfare whatever the variability of the natural environ-ment.

Tonkin in the north, in the 17th and 18th cen-turies was partly caused by political institutions, exacerbating such famine and poverty conditions, (particularly the Nguyen dynasty the impact of famines and poverty within the peasant societies) (Nguyen The Anh, 1995). Despite the numerous

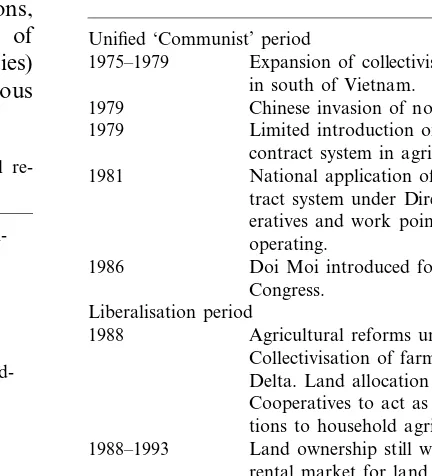

Table 2

A chronology of major political changes in Vietnam since reunification in 1975a

Unified ‘Communist’ period

1975–1979 Expansion of collectivised agriculture in south of Vietnam.

Chinese invasion of northern Vietnam. 1979

1979 Limited introduction of household contract system in agriculture. 1981 National application of household

con-tract system under Directive 100; coop-eratives and work point system still operating.

Doi Moi introduced following Party 1986

Congress. Liberalisation period

1988 Agricultural reforms under Decree 10. Collectivisation of farms in Mekong Delta. Land allocation on lease system. Cooperatives to act as service opera-tions to household agriculture. Land ownership still with the state. A 1988–1993

rental market for land emerges even though illegal.

1993 Land Law instigates 15 year and longer leases of agricultural land.

aSource: adapted from Fforde and de Vylder (1996) and

others. Table 1

A chronology of major political changes in Vietnam till re-unification in 1975a

Pre-european colonial period (Chinese colonialism and in-dependence)

111 BC–905 AD Chinese colonial rule with numerous revolts

905–1427 Alternate independence and Chinese colonial rule up to the Ming dynasty 1427–1786 Independence under Le dynasty

includ-ing division of north and south Viet-nam under two viceroys from 1627 1774 Revolt in northern provinces led by

Tay Son brothers over high taxes 1786–1859 Unification under Tay Son and Nguyen

dynasties European colonial period

1859 First French invasion of Cochinchina Concession of all of Cochinchina to 1867

France by Hue Court

Expansion of territorial interests and 1867–1883

trade monopolisation by French till all of Vietnam under French rule, under Annam, Tonkin and Cochinchina. 1884–1927 Anti-colonial resistance in various

re-gions of Vietnam with periodic revolts Formation of Vietnamese Nationalist 1927

Party under Ho Chi Minh

1930–1931 Nghe-Tinh soviet movement in central Vietnam

Japanese invasion of Indochina with 1940

agreement from French administration ‘Communist’ period

1945 Surrender of Japan and Declaration of Independence by Ho Chi Minh (2nd September 1945)

1946–1954 Franco–Vietnamese War concluded with victory at Den Bien Phu Division into North and South Viet-1954

nam under Geneva Agreement 1960 Formation of National Liberation

Front of South Vietnam

US ground troops in Vietnam and 1965–1968

bombing of northern Vietnam Reunification of Vietnam 1975–1976

aSource: adapted from Hy Van Luong (1992), Popkin

(1979) and others.

revolts and political upheavals in the course of these centuries, however, much of lowland society appears to have retained its underlying hierarchi-cal social structures.

The French expansion of its colonies into Southern Vietnam from 1859 onwards heralded a shift in the operation and governance of Vietnam and in the institutions of government and hence of land management in particular. The French colony was expanded piecemeal through a series of invasions and treaties. The French divided the Vietnamese area formally into the three states of Tonkin and Annam in the north and central, and Cochinchina in the south (Table 1), areas which had only a short precedent in Vietnamese history (Wiegersma, 1988).

limited, formal institutionalisation of capitalism in Vietnam in the lowland agricultural areas. This became manifest in the creation of private landlord classes who controlled land and rented it to landless peasants, thereby replacing collective labour with waged labour. This capitalist penetration was, however, limited to these rice growing areas and to where tax collection systems were instituted. Many parts of Vietnamese society resisted the institutions of French colonialism and restricted their impact (Ngo Vinh Long, 1973).

The influence of imported colonial institutions are much less in areas more remote for the colonists than the accessible lowland delta areas. In all of highland Vietnam, forest resources were declared state property by French colonists but were admin-istered throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries solely through taxes. The ethnic minorities of the uplands, including the Hmong and Dzao minori-ties, continued to control land and forest areas through customary law and social organisation (Nguyen Van Thang, 1995).

In addition, as discussed above, there were stark regional differences within the land use and tenure systems in the late 19th century, whereby Tonkin and Annam were not as influenced by French colonisation as Cochinchina. Landlords in some regions acted as traditional patriarchs, tended to live within the villages where they owned land and were therefore more likely to remain part of any traditional insurance during periods of drought or flood. But critically, the French colonial system also allocated land to non-traditional landlords who were largely absentee and who became the focus for peasant resistance and unrest.

An example of revolt during this colonial period is the setting up of the Soviets of Nghe An and Ha Tinh in northern Annam in 1930 and 1931. This rebellion serves to illustrate the theme of disso-nance between underlying social institutions and the imposed institutions of colonial capitalism, in the context of coping with a variable and risky environment. The rebellion leading to the setting up of these earliest Communes is described in detail by Scott (1976; pp. 114 – 119). Rapid reduction in agricultural prices precipitated by significant falls in the international commodity prices in agriculture

in the late 1920s, triggered unrest in Annam. Under the colonial administrations, waged peasants were subject to relatively stable subsistence expenditures such as clothing and fuel, but also to high levels of head and land taxes, and ultimately debts. The levels of individual debt in Annam remained un-changed despite a threefold decrease in paddy rice and (major cash crops) output prices between 1929 and 1934.

A compounding local factor in the Annam region leading to rebellion and unrest, was low agricul-tural production caused by low rainfall, leading to famine. In this context famine is defined in terms of absolute food shortages and emergency switch-ing to wild famine foods as nutrition sources. Low rainfall in the region in 1929 delayed transplanting of the first rice crop in that year. Drought exacer-bated by dry winds throughout 1930 and spring of 1931, resulted in four rice crops in succession being lost.

The rebellions involved civil unrest, partly or-ganised by the Communist party which had been founded during the 1920s, and involving local level protest and direct action against the tax system and local officials. The two villages of Nghe An and Ha Tinh in Annam declared themselves as independent collectivised areas, overthrowing the colonial tax raising institutions of the villages, and returned to traditional collective allocation of labour. The rebellion in these locations, facilitated by the Com-munist Party resulted from the coincidence of the policies of colonial administrators who ensured that the peasants bore the cost of recession and the drought conditions.

Colonial occupation by imposing the institutions of capitalism, was sowing the seeds of potential peasant revolt. The Soviets were short lived, but remained a symbol for more equitable alloca-tion of resources under a future independent Vietnam. Scott’s (1976) analysis of this event3

3Scott’s approach to the motivations of the peasantry under

demonstrates that the institutional setting, in this case as dictated by colonial powers, in effect clashed with underlying culture and impacted on the actual use of land.

But the example of the Annam Soviets also illustrates the interlocking of the resource endow-ment, climate, institutional and political economy aspects of social evolution. External institutional forces, both benevolent and malevolent play a major role in the evolution of land use and social organisation. Other social upheavals leading to famine in Vietnam are associated as much with political and social strife as with periodic coinci-dence of extreme climate events (as argued in the context of famine more generally by Sen, 1981). The food shortages and hardships of the 1930s, for example, had a less significant impact on Vietnam’s population than those caused by wartime upheavals in 1945. As the Japanese occu-piers took over Vietnam in 1945 after the fall of the Vichy-French authority, a breakdown in food distribution resulted. In the resulting famine in northern Vietnam, one million people are re-ported to have died (Jamieson, 1993; p. 191). So although not applicable in all the crises facing Vietnam in the 20th century, external climate risks have played a role in some famine situations and in the evolution of land use and social organisation.

Collective action surrounding mitigation and coping with climatic extremes in Vietnam, such as through civil defense, represents an important as-pect of risk spreading and institutional adaptation to changing environmental risks. The collective action system in the rural economy is argued to have been at its most effective during wartime, due to the readiness for breaching of the Red River Delta dikes by aerial bombardment such as that attempted in April to July 1972 for example (documented by Lacoste, 1973). Aerial bombing was targeted at the coastal and inland river dikes ‘‘at points where their rupture, given the varie-gated conditions of the delta, would prove a catalyst for even greater disaster and more deaths’’ (Lacoste, 1973; p. 3).

In 1972 the production brigades from the agri-cultural co-operatives repaired the breaches caused by bombing in 96 sites, principally in Thai

Binh and Nam Ha Provinces in the Red River Delta area of North Vietnam. There was unusu-ally low precipitation in 1972 such that the low-ly-ing delta Provinces avoided large-scale floodlow-ly-ing from the breaches. Thus the effective communal systems of land and resource management act as the primary institutions for collective security. Collectivised agriculture in North Vietnam al-lowed universal access to evacuation and health provision organised at the Commune and District level.

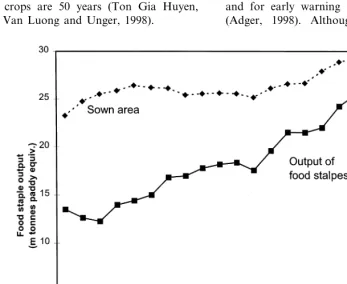

3.3. The communist and market-oriented periods

Following the re-unification of Vietnam in 1975 after three decades of the Indochina Wars, Viet-nam entered a period of evolution of its commu-nist practice, first through implementation of collectivisation and of state-owned enterprises in both north and south (Table 2). Collectivisation had begun in the north around 1955, such that by 1960 86% of rural households were members of co-operatives. In the south little or no collectivisa-tion occurred prior to 1975 (Kerkvliet and Selden, 1998). The period of attempted collectivisation of the whole country in the late 1970s is character-ised as a period of stagnation in agricultural output and low economic growth (Fig. 1). The imposition of collectivisation in the south in 1975 was resisted and led to a sharp fall in agricultural output in that region.

(renovation), abandoning industrialisation in fa-vour of agricultural-led growth.

The fast evolving situation of land tenure and control in the Doi Moi period has been directed by a resolution of the National Assembly in 1988 (Resolution No. 10) which formalised a full con-tract system of household responsibilities in agri-culture, and by a Land Law in 1993 which, in effect, allows long-term lease of land from the state and allows these leases to be tradeable. The 1993 Land Law states that ‘land is an extremely valuable national resource on which economic, cultural, social, security and national defence are constructed’. At present all land is owned by the state and agricultural co-operatives retain control over the distribution of inputs and provision of irrigation. But under the Law, households are allocated Red Books in which their leases for annual crops are 20 years and on forest land and perennial crops are 50 years (Ton Gia Huyen, 1994; Hy Van Luong and Unger, 1998).

The present day situation is therefore character-ised as rapid increases in marketed agricultural output facilitated both by incremental changes in the distribution system and higher real prices to farmers, as well as to incentives to invest in private agricultural land. Thus economic liberali-sation in the agricultural sector has brought about some increases in agricultural production, but with complex social and political consequences within the rural agrarian economy (e.g. Watts, 1998; Hy Van Luong and Unger, 1998).

Local government institutions from the Province to the District level have taken advan-tage of increased autonomy as a result of Doi Moi, but have become less influential in resource use since agricultural land has been allocated to private individuals. Institutional adaptation con-cerning flooding and typhoon impacts have led to a reduction of resources for sea dike maintenance and for early warning systems in coastal areas (Adger, 1998). Although Vietnam’s transition

from state central planning is often heralded as being successful from a macro-economic perspec-tive, this masks some important aspects of social vulnerability. Collective action for the manage-ment of risk by state institutions has been under-mined by inertia in some aspects of the decentralised state planning system, while parallel spontaneous re-emergence of civil society institu-tions form a counter-balancing institutional adap-tation. Thus formal institutions are seeking to maintain their resources, powers, and their au-thority in this area at the expense of collective security. Informal institutions have offset some of these negative consequences of market liberalisa-tion and the reducliberalisa-tion of the role of government, by evolving collective security from below.

3.4. Summarising cultural and institutional e6olution

The underlying cultural homogeneity of the lowland Vietnamese from the ‘traditional’ or pre-European colonial era is an important facet in the influence on both the sustainability of the institu-tions which governed the country throughout its history, and on the technologies and mechanisms of resource use. For lowland Vietnam, hierarchi-cal central government control appears to have been a necessary condition for the maintenance of the technology on which the fertility and security of the agricultural system was based, namely the sophisticated irrigation and dike system. Under this argument, technology and geography strongly influence what political system is best suited to economic advancement: it is only the excessive mismanagement of the ‘natural order’ of govern-ment, particularly under colonial times, which causes breakdowns in the institutional system.

The influence of Confucianism on the Viet-namese relationship with the institutions of gov-ernment is highly controversial among Vietnamese, as well as western, commentators and historians. The influence of the humanist philoso-phy of Confucianism (with its emphasis on social and political issues) on the adoption of commu-nism, as well as the predisposition of Confucianist thinking towards radical rather than incremental change, are widely discussed. From the brief

re-view presented here it appears that Vietnamese society persevered in land use and technological advancement under negative political conditions for long periods in their history till they managed to spark revolutionary change. However many aspects of the observed collective government of Vietnam in the pre-European colonial era cannot be characterised as Confucian, in respect to strong central government outside the patriarchal and village based system. In addition, the pragmatism and persistence of the Communist government in the past half-century demonstrate the flexibility and absence of Confucian hegemony in Viet-namese institutional structures.

There are, therefore, fundamentally different ways to describe the interaction of Vietnamese culture with the institutions of government and land use. These differences are based around the conceptualisation of the Vietnamese peasan-try as either hierarchical or rational and individu-alist:

‘‘Economic decisions were not made either rationally or morally by Vietnamese peasants. Decisions were made by the village leaders and the family patriarchs in the context of tradi-tional and modern realities… peasant motiva-tions are predominantly determined by the mixture of old and new political-economic in-terrelationships and old and new technologies’’ (Wiegersma, 1988; p. 15).

collected stores of grain in years of successful harvests and held reserves of food and material for flood or drought years. In the European colo-nial era the institutions of capitalism, private property and private ownership were introduced to Vietnam to a large extent for the first time. They are superimposed on the essentially tradi-tional collective land tenure system. These im-posed colonial institutions were successful in the sense that they persisted and penetrated the agrar-ian society up till the time when the global agri-cultural depression of the 1920s disturbed this non-resilient institutional system. The colonial governments attempted to transfer the impact of the depression onto the peasants and failed to fulfill the security functions of central government during drought periods, thereby unleashing peas-ant rebellion against the system in the early 1930s, and promoting the nationalist cause.

The post-colonial period is characterised as a period when the government system was legiti-mated by its apparent harmony with underlying cultural influences, given nationalism and the ex-ternal forces which threatened the Vietnamese state in this period. The system of government adopted under the Communist collectivisation was particularly effective in dealing with the threat of external forces, from diverse sources such as climate extremes or from wartime aerial bombing (see Lacoste, 1973; Thrift and Forbes, 1986). The decollectivisation period, outlined in Table 2, involves radical changes in the institu-tional framework of resource use and the in-creased exposure of local level resource users to external forces, both in the policy environment and perhaps to the impacts of extreme events in nature.

The major institutional changes which have occurred in the decollectivisation period involve the atomisation of land tenure in the progression from the household contract system of the early 1980s to the effective privatisation of agricultural land by individual households. In the agriculture sector there have been dramatic increases in agri-cultural production and marketing since the mid 1980s, as evidenced both at the national and at District levels, partly due to increased use of external inputs, primarily capital, and partly to

management and food distribution. Outside the land use sector, the state owned enterprise sector has been emasculated and the country opened to foreign investment. Kolko (1997) argues that the explicit social justice goal of the Democratic Re-public of Vietnam government since reunification has been eroded by the liberalisation process, as evidenced by changes in the distribution of in-come (see Adger, 1999a). Hy Van Luong and Unger, 1998 and Ngo Vinh Long (1993) both argue that the impetus for reform is greatest where collectivisation and stagnation of the econ-omy have been greatest.

In terms of the capacity to cope with environ-mental risk, however, it is important to establish the potential for cultural and institutional changes and feedbacks within modern Vietnamese society. The skewed distribution of income may be offset by strengthening and re-emergence of kinship ties within Vietnamese agrarian society, as argued for example by Hy Van Luong (1993). In addition to formal changes in the 1993 Land Law, there is evidence of a re-emergence of local level institu-tions associated with local collective action, and with economic activities. Some of these institu-tions, such as local level credit schemes, or Street Associations, have always been manifest within villages but have been redefined in the Doi Moi period. The implications of the liberalisation pro-cess on the interactions between land use, re-sources and climate risk are most dependent on these institutional changes, which themselves have far reaching consequences.

decreasing reliance on climate dependent re-sources, this has been at some cost to collective security. At the national level there are explicit trade-offs in the investment in large scale in-frastructure for development and security. In the Mekong river system for example, investment in hydro-electric dams to provide electricity for ur-ban development affects both salinity and risks of flooding in the delta. Such investment and land use decisions are clearly tied to transboundary national and regional political imperatives (Sned-don and Binh Thanh Nguyen, 1999). Thus the institutional and cultural influences on land use and environmental and climate risks is an ongoing evolutionary process.

4. Implications for researching vulnerability and adaptation

The conclusions from this paper are twofold: firstly on the nature of the Vietnamese case in vulnerability to climate extremes, and secondly on the nature of coevolutionary systems and implica-tions for adaptation to environmental change. First, Vietnam has a long history of intervention-ist management in its natural environment for maximisation of output in niches of natural re-source use. Vietnam is a largely agrarian society with almost four fifths of its population in rural areas. In addition, Vietnam has a relatively equi-table land allocation as a result of collectivisation and decollectivisation within two decades, and rapid economic growth in urban growth poles. Historically, Vietnam has faced external pressures and feedbacks including security in the context of invasion and political upheaval, ownership and tenure arrangements; security from climate threats with technological dependence, and the evolution of social institutions. The present day economic structure has come about by the confluence a myriad of social, cultural and economic driving forces and evolving institutions described in this paper.

A more specific purpose of this paper is to focus on the relationship between land use, and institutions with climatic and other risks. In rela-tion to Vietnam it is argued that the topography,

climate and government structures of lowland Vietnam have facilitated investment in climate smoothing water regulation technology over the past millennium. This is particularly apparent in lowland regions where the ‘traditional’ Viet-namese institutions and society evolved within the physical parameters. Further, periodic climate ex-tremes and the social coping mechanisms associ-ated with them have been embedded in the prevailing institutional structures of collective land use. Hence climatic extremes can play a role in evolutionary social and environmental change. These conclusions in the Vietnamese case do not ascribe determinant relations within such evo-lutions. Rather, as pointed out by Post (1980), they are observations of the influence of climate on longer timescales than interannual variability. The evolutionary approach adopted here attempts to provide a focus for examining the processes of social and economic change underlying land use in Vietnam. The coevolutionary perspective does not, however, develop explicit policy prescriptions based on such analysis. As an approach similar to that of researching climate change by analogy (Glantz, 1991), coevolutionary analysis can be used to ‘identify societal strengths and weaknesses [to future or present conditions] so that the strengths might be exploited and weaknesses ad-dressed’ Glantz (1991); p. 31).

A second conclusion of this paper is that the approach outlined is not a descriptive model of the state of land use or the institutional system around it, but rather a picture of the interrelated processes forming the society-environment inter-actions. The historical investment in climate smoothing technologies observed in all parts of the agricultural world has reduced the risk from climate extremes. It has been argued that such large scale management of ecosystems gives soci-ety a misplaced confidence and freedom from climatic risk which nature may not permit (Bur-roughs, 1997). This lesson has only partially been learned, given the impact of surprises and risk on riverine floods, for example, and in the manage-ment of numerous other ecosystems (e.g. Myers and White, 1993; Gunderson et al., 1995).

dynamic processes, with major non-linearities and thresholds. This is as true for the historical tion of institutions as it is for ecosystems: evolu-tionary change of political and economic systems are themselves punctuated by radical upheavals and changes in state. An historical dimension to any analysis of social vulnerability and adaptation is therefore necessary for understanding the parameters of change. The historical dimension also provides pertinent historical analogies of present day and potential environmental risks.

Acknowledgements

Funding by the UK Economic and Social Re-search Council, Global Environmental Change Programme and by the British Academy Commit-tee for South East Asian Studies (Award No. L320253240) is gratefully acknowledged. I thank Mick Kelly for discussions and for the comments of two anonymous referees which improved the manuscript. The final version remains my own responsibility.

References

Adams, J., 1986. Peasant rationality: individuals, groups, cul-tures. World Development 14, 273 – 282.

Adger, W.N., 1998. Observing Institutional Adaptation to Global Environmental Change: Theory and Case Study from Vietnam. Global Environmental Change Working Paper 98-21, Centre for Social and Economic Research on the Global Environment, University of East Anglia and University College London.

Adger, W.N., 1999a. Exploring income inequality in rural, coastal Vietnam. J. Dev. Studies 35 (5), 96 – 119. Adger, W.N., 1999b. Social vulnerability to climate change

and extremes in coastal Vietnam. World Dev. 27, 249 – 269. Alexander, S.E., Schneider, S.H., Lagerquist, K., 1997. The interaction of climate and life. In: Daily, G.C. (Ed.), Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosys-tems. Island Press, Washington, DC, pp. 71 – 92. Allanson, P., Murdoch, J., Garrod, G., Lowe, P., 1995.

Sus-tainability and the rural economy: an evolutionary perspec-tive. Environ. Planning A 27, 1797 – 1814.

Anderson, J.L., 1981. History and climate: some economic models. In: Wigley, T.M.L., Ingram, M.J., Farmer, G. (Eds.), Climate and History: Studies in Past Climates and their Impact on Man. Cambridge University Press, Cam-bridge, pp. 337 – 355.

Beresford, M., 1990. Vietnam: socialist agriculture in transi-tion. J. Contemp. Asia 20, 466 – 486.

Bray, F., 1986. The Rice Economies: Technology and Devel-opment in Asian Societies. Blackwell, Oxford.

Burroughs, W.J., 1997. Does the Weather Really Matter? The Social Implications of Climate Change. Cambridge Univer-sity Press, Cambridge.

Clark, N., Juma, C., 1988. Evolutionary theories in economic thought. In: Dosi, G., Freeman, C., Nelson, R., Silverberg, G., Soete, L. (Eds.), Technical Change and Economic Theory. Pinter, London, pp. 197 – 218.

Daly, H.E., 1992. Steady State Economics, 2nd Edn. Earth-scan, London.

de Vries, J., 1980. Measuring the impact of climate on history: the search for appropriate methodologies. J. Interdisiplin. Hist. 10, 599 – 630.

Dosi, G., Freeman, C., Nelson, R., Silverberg, G., Soete, L. (Eds.), 1988. Technical Change and Economic Theory. Pinter, London.

England, R.W. (Ed.), 1994. Evolutionary Concepts in Con-temporary Economics. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

Fforde, A., 1987. Socio-economic differentiation in a mature collectivised agriculture: north Vietnam. Sociologia Ruralis 27, 197 – 215.

Fforde, A., de Vylder, S., 1996. From Plan to Market: the Economic Transition in Vietnam. Westview, Boulder. Glantz, M.H., 1991. The use of analogies in forecasting

soci-etal responses to global warming. Environment 33 (5), 10 – 15, 27 – 33.

Gunderson, L.H., Holling, C.S., Light, S.S. (Eds.), 1995. Bar-riers and Bridges to the Renewal of Ecosystems and Insti-tutions. Columbia University Press, New York.

Hodgson, G.M., 1994. Precursors of modern evolutionary economics: Marx, Marshall, Veblen and Schumpeter. In: England, R.W. (Ed.), Evolutionary Concepts in Contem-porary Economics. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, pp. 9 – 35.

Hy Van Luong, 1992. Revolution in the Village: Tradition and Transformation in North Vietnam 1925 – 1988. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu.

Hy Van Luong, 1993. Economic reform and the intensification of rituals in two north Vietnamese villages, 1980 – 1990. In: Ljunggren, B. (Ed.), The Challenge of Reform in In-dochina. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, pp. 259 – 291.

Hy Van Luong, Unger, J., 1998. Wealth, power and poverty in the transition to market economies: the process of socio-economic differentiation in rural China and northern Viet-nam. China J. 40, 61 – 93.

Ingram, M.J., Farmer, G., Wigley, T.M.L., 1981. Past climates and their impact on man: a review. In: Wigley, T.M.L., Ingram, M.J., Farmer, G. (Eds.), Climate and History: Studies in Past Climates and their Impact on Man. Cam-bridge University Press, CamCam-bridge, pp. 3 – 50.

Kearney, M., 1996. Reconceptualising the Peasantry: Anthro-pology in Global Perspective. Westview, Boulder. Kerkvliet, B.J.T., Selden, M., 1998. Agrarian transformations

in China and Vietnam. China J. 40, 37 – 58.

Kolko, G., 1997. Vietnam: Anatomy of a Peace. Routledge, London.

Lacoste, Y., 1973. An illustration of geographical warfare: bombing the dikes on the Red River, North Vietnam. Antipode 5, 1 – 13.

Lamb, H.H., 1995. Climate, History and the Modern World, 2nd Edn. London, Routledge.

Myers, M.F., White, G.F., 1993. The challenge of the Missis-sippi flood. Environment 35 (10), 7 – 9, 25 – 35.

Nelson, R.R., Winter, S., 1982. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Nelson, R.R., 1994. The coevolution of technologies and institutions. In: England, R.W. (Ed.), Evolutionary Con-cepts in Contemporary Economics. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, pp. 139 – 156.

Ngo Vinh Long, 1973. Before the Revolution: the Vietnamese Peasants Under the French. MIT Press, Cambridge. Ngo Vinh Long, 1993. Reform and rural development: impact

on class, sectoral and regional inequalities. In: Turley, W.S., Selden, M. (Eds.), Reinventing Vietnamese Social-ism: Doi Moi in Comparative Perspective. Westview, Boul-der, pp. 165 – 207.

Nguyen The Anh, 1995. Historical research in Vietnam: a tentative survey. J. S. E. Asian Studies 26, 121 – 132. Nguyen Van Thang, 1995. The Hmong and Dzao peoples in

Vietnam: impact of traditional socio-economic and cultural factors on the protection and development of forest re-sources. In: Rambo, A.T., Reed, R.R., Le Trong Cuc, DiGregorio, M.R. (Eds.), The Challenges of Highland Development in Vietnam. East West Centre, Honolulu, pp. 101 – 119.

Norgaard, R.B., 1994. Development Betrayed: The End of Progress and a Coevolutionary Revisioning of the Future. Routledge, London.

O’Riordan, T., Jordan, A., 1999. Institutions, climate change and cultural theory: towards a common analytical frame-work. Global Envir. Change 9, 81 – 93.

Popkin, S.L., 1979. The Rational Peasant: the Political Econ-omy of Rural Society in Vietnam. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Post, J.D., 1980. The impact of climate on political, social and economic change: a comment. J. Interdisciplin. Hist. 10, 719 – 723.

Rambo, A.T., 1973. A Comparison of Peasant Social Systems of Northern and Southern Vietnam. Centre for Vietnamese Studies, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale. Rambo, A.T., Reed, R.R., Le Trong Cuc, DiGregorio, M.R.

(Eds.), 1995. The Challenges of Highland Development in Vietnam. East West Centre, Honolulu.

Ruttan, V.W., 1988. Cultural endowments and economic de-velopment: what can we learn from anthropology? Econ. Devel. Cultural Change 36 (Suppl.), 247 – 271.

Sachs, J., 1997. The limits of convergence: nature, nurture and growth. The Economist 14th June, 19 – 22.

Samuels, W.J., 1995. The present state of institutional eco-nomics. Camb. J. Econ. 19, 569 – 590.

Schneider, S.H., Londer, R., 1984. Coevolution of Climate and Life. Sierra Club Books, San Francisco.

Scott, J.C., 1976. The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebel-lion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia. Yale University Press, New Haven.

Sen, A.K., 1981. Poverty and Famines: an Essay on Entitle-ment and Deprivation. Clarendon, Oxford.

Sneddon, C., Binh Thanh Nguyen, 1999. Politics, ecology and water: the Mekong Delta and development of the lower Mekong basin. In: Adger, W.N., Kelly, P.M., Nguyen Huu Ninh (Eds.), Living with Environmental Change: Social Vulnerability, Adaptation and Resilience in Vietnam. Routledge, London, in press.

Thrift, N., Forbes, D., 1986. The Price of War: Urbanisation in Vietnam 1954 – 85. Allen and Unwin, London. Ton Gia Huyen, 1994. The 1993 Land Law and land policies.

In: Howard, C. (Ed.), Current Land Use in Vietnam: Proceedings of the Second Land Use Seminar, Bac Thai. Land Use Working Group, Hanoi and International Insti-tute for Environment and Development, London, pp. 12 – 23.

Vietnam General Statistical Office, 1995. Statistical Yearbook 1994. Statistical Publishing House, Hanoi.

Watts, M.J., 1998. Recombinant capitalism: state, de-collec-tivisation and the agrarian question in Vietnam. In: Pick-les, J., Smith, A. (Eds.), Theorising Transition: The Political Economy of Post-Communist Transformations. Routledge, London, pp. 450 – 505.

Wiegersma, N., 1988. Vietnam: Peasant Land, Peasant Revo-lution. Macmillan, London.