I

S THERE A

‘T

HIRD

W

AY

’

FOR

T

RADE

U

NIONISM IN

H

ONG

K

ONG

?

NGSEKHONG* ANDOLIVIAIP**

O

ver the past two decades, Hong Kong has been caught in the various dynamism of economic restructuring, political reversion to China and ‘late urbanism’, leading to a new constellation of social and industrial problems, which have been, so far, inadequ-ately tackled by the government and by private businesses. Trade unions in Hong Kong face challenges to their conventional role, which are largely related to the rise of atypical employment and the increasingly transient nature of the workplace as a unit of work and employment. The present paper suggests that, in response to these adversities, trade unions in Hong Kong have taken strategic moves. There are emerging symptoms that the trade unions are restructuring and evolving a functional role in organising the neighbourhood community as a type of ‘third sector’ organisation outside and in parallel to their conventional occupational domain.INTRODUCTION

Organised labour in Hong Kong decreased over the three successive decades after WW2, due to many factors that have been documented in detail in the literature (England and Rear 1981; Turner et al. 1980; Thurley 1983, 1988; Roberts 1964; Turner et al. 1991; Ng and Warner 1998). A thirteen-year period of political transition before the 1997 changeover of sovereignty gave a mixed impetus to the development of trade unions, and enshrined them as political agencies to represent the working people at the law-making assembly (the Legislative Council). However, they remained essentially docile at the workplace level (Ng and Rowley 1997, pp. 85–9; Ng 1997, pp. 666–8). At present, there are signs that Hong Kong’s labour unions are developing a functional role at the neighbourhood community level, outside and in parallel to their conventional occupational ‘jurisdiction’ as workers’ combinations. With increased activity in community work, these unions appear to be converging with ‘third sector’ organisations and non-governmental agencies (NGO) located outside public and private business domains and are performing an increasingly crucial role as personal service providers within the post-industrial society (Giddens 1998, pp. 80–5).

The above phenomenon of ‘convergence’, if placed in a theoretical perspective, echoes the ‘third way’ thesis as an exposition of a liberal approach to the renewal of ‘social democracy’ within the post-industrial societies of late (modern/post-modern) urbanism. The ‘third way’ thesis as a critique of post-modernity and globalisation, advanced by sociologists like Giddens (1998, 2000), envisages a wholistic agenda for social and political institutions to be reformed and re-organised, along a ‘mid-way’ course between the extreme alternatives of ‘American market liberalism’ and ‘Soviet-style state authoritarianism’. Particular attention is paid to an increasingly visible vacuum of anomie and social dis-integration created at the grass-roots level by the drift of ‘marketplace’ competi-tion. Among the symptoms of such pathos are widened wealth and income inequalities, the subdued workplace as the provider of secure and long-term employment, the eclipse of the family, and the withering away of the welfare state (Giddens 1998, chapter 2). Moreover, the success ethos associated with the imperative of competition in a globalised horizon also breeds a tide of ‘new individualism’ and ‘elitism’, accompanied by a body of assumptions and values that sanctify images of the ‘autonomous individual’, ‘me-first’ society and pervasiveness of a ‘me’ generation (Giddens 1998, p. 35).

The ‘third way’ thesis argues for a program of renewing and strengthening the neighbourhood community, through sponsoring the work of ‘third sector’ voluntary organisations as a key to arresting and correcting the above drift, which threatens to alienate the person and emasculate the fabric and integration of society. Even the postmodern workplace has become equally fragile and eclipsed, largely because of the popular practice of flexi-hiring (void of the parties’ mutual commitment), habitual down-sizing and a market-sanctioned system of rewarding for competitive competency, performance and success. The creed for elitism and individualism, therefore, exaggerates the gap between the able and less-able, leading to an even sharper polarisation between the rich and poor, and between those who ‘have’ and those who ‘have not’ (Giddens 1998, pp. 104–11). The occupational and industrial unions, alongside other ‘mainstream’ established social institutions, like the family and public agencies (notably those organising national health and centrally administered provident/medical provisions), are increasingly trivialised, run-down or hived-off. Therefore, there is a need either to re-vitalise these established ‘mainstream’ institutions or to substitute them with newer forms, such as ‘third sector’ organisations. In this connection, a hiatus appears in the future of the trade union institution.

into a form of ‘third sector’ organisation in addressing the community neighbourhood as the ‘constituency’ and focal point of their work and services. In other words, Hong Kong trade unions can be pioneer ‘vanguards’ by experi-menting and piloting with community unions to build a new model of trade unionism. However, before presenting the Hong Kong case, it is useful to note briefly the global phenomenon of the decline and exhaustion of trade unions.

GLOBAL PHENOMENON OF DECLINING TRADE UNIONISM

An exhaustion in trade unionism among industrially advanced economies appears to coincide with the problems of stagnation experienced in these economies during the 1970s and 80s (Hyman 1994, pp. 1–14). The decline in the industrial strength of organised labour was largely evident in the trend of falling union membership across almost every developed industrial nation, as reported in a 1996 worldwide study of the problems and prospects of unionism sponsored by the International Labour Organisation (ILO)(Olney 1996, p. 2).

It has been argued that trade unionism has become exhausted partly because of problems that are endemic to labour movements. Mature and established trade unionism inherently drifts towards organisational bureaucracy, even oligarchic control, especially as collective bargaining involves expensive administrative activity. The constant and periodical re-negotiation of the collective agreement has not only sustained a ‘we–they’ divide and even created hostility between the two sides, but it has also burdened business enterprises with a perpetuated upward drift of wages and associated labour costs. Multi-unionism at enterprises is also liable to complicate workplace haggling and breed frequent industrial strife on inter-union rivalry for employers’ recognition (see Sisson and Storey 2000; Marginson and Sisson 1990; Brown et al. 1995). In addition, the changing composition of the occupational structure, with white-collar service workers now predominating over the industrial blue-collar workers (hitherto the ‘working class’ vanguards of the labour movement), has not been conducive to the susten-ance of working class consciousness at the core of the ‘mainstream’ unionism and its ideology.

union recognition extended by enterprise management in Britain (see, for example, Storey and Sisson 1993, pp. 202–3).

At the macro level, the wider context of economic adjustments has also given rise to new and changing perimeters affecting employment and organised labour. Post-war Europe and America were afflicted by the widespread and lingering effects of stagflation in the aftermath of the petrol squeeze during the late 1970s and early 1980s. In order to lift themselves out of prolonged ‘doldrums’, there were widespread endeavours to borrow from the late developing East Asian nations, notably Japan, alternative prescriptions for organising work, business and economic activities (Dore 1990, afterword) and search for new formulae and initiatives to help revitalise and advance their lukewarm business and economy. There followed a popular trend across Europe and America of corporate waves directed at business and industrial restructuring, alongside efforts at de-bureaucratisation, deregulation and privatisation of national enterprises and public sector activities paralleled by labour market reforms.

In particular, flexi-hiring, which has been practised on a widening scale among enterprises and economies within the ‘First World’ domain, leads to the prolifer-ation of a variety of ‘atypical employment’ types, including part-time engage-ment, short-term fixed contract hiring and temporary seasonal working. The transient nature of hiring for ‘non-regulars’ often means that these workers lack a stable attachment to a workplace or employing unit. Such an erosion has evidently made the ‘casual’ workforce less amenable to the organisational work of unions. The relative growth of atypical employment has, therefore, presented trade unions today with new challenges of membership maintenance and stabilis-ation. In addition, collective bargaining by unions has shifted its focus from the industry-wide level to the workplace level, and is often obsessed with the thorny and passive task of defending an apprehensive workforce from the perils of ‘downsizing’––eclipsing previous endeavours at wrestling from employers concessions on pay hikes.

LABOUR ORGANISATIONS INHONGKONG: YESTERDAY’S HIATUS AND

TODAY’S CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS

The worldwide syndrome of union exhaustion has also affected and emasculated the trade union system in Hong Kong. Furthermore, the challenges poised to organised labour in this East Asian city have been compounded and exaggerated by its complex historical background, fragmenting the pluralistic labour move-ment, within which, small, multiple, competing and ideologically hostile unions have proliferated (Turner et al. 1980, pp. 25–32). Some of the key factors helping shape the movement’s present posture are worth noting.

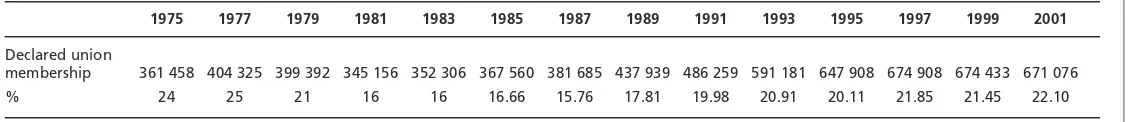

The weakening of the labour movement’s solidarity was evidenced by a creeping retreat during the late 1970s and early 1980s in the waged labour force’s union density and a decline in the overall unionised population size (see, for example, Turner et al. 1991, pp. 55–7) (see Table 1).

This ‘de-unionisation’ phenomenon was later given a major impetus by Hong Kong’s industrialisation and post-industrial development. Mirroring the economy’s advances towards tertiary service production, there has been a con-spicuous growth of white-collar occupations, paralleled by a retreat of the indus-trial blue-collar groups. Since the blue collar groups always constituted the ‘vanguards’ of the mainstream labour movement, their decline contributed directly to the stagnation of Hong Kong unionism during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Hong Kong unionism had to wait until the pre-1997 political transition to stimulate its shrinking membership (Turner et al. 1991, pp. 98–102; Ng 1997). A second factor that helps explain the docility of Hong Kong trade unionism as a workplace institution is the relative absence of a strong industrial infra-structure sustaining the functioning of trade unions in handling employment relations at either the industry or workplace level. To a large extent, this feature was a hangover from historical legacies. The Chinese labour movement in its pre-war heydays embraced Hong Kong as a key bastion, but it was neither keen nor able to consolidate a power base at the grass-roots workplace level, largely because of its bias towards a politico-ideological mission of acting as a popular mass organ of the leading political party (either of the feuding Nationalist and Communist parties). This political obsession implied a traditional aloofness held by these unions about building a collective bargaining system equivalent to those in western industrialised economies. Instead, there is a persistence of abstention of these ‘veteran’ unions from active shopfloor organisation, so that an established shop steward system is conspicuous in its absence from Hong Kong workplaces. In addition, there is an entrenched apathy by Hong Kong’s employers in recognising trade unions’ purpose of collective bargaining. Lacking an effective power-base anchored upon collective bargaining, the unions were limited in articulating and protecting the employees’ interests when business enterprises at the turn of the century began to emulate their western counterparts and launch waves of restructuring exercises aimed at bettering their performance and effici-ency. Downsizing, de-establishment, lay-offs and wage cuts were levied freely upon the local workforce, with hardly any effective resistance led by the labour unions (see, for example, Chan et al. 2000, pp. 88–91).

‘T

HIRD

W

AY

’

FOR

T

RADE

U

NIONISM

IN

H

ONG

K

ONG

?

383

Table 1 Union participation rates (%) and membership in Hong Kong since 1975

1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001

Declared union

membership 361 458 404 325 399 392 345 156 352 306 367 560 381 685 437 939 486 259 591 181 647 908 674 908 674 433 671 076

% 24 25 21 16 16 16.66 15.76 17.81 19.98 20.91 20.11 21.85 21.45 22.10

collective bargaining because of its historical absence. Such an ‘institutional openness’, alongside the unions’ image as occupational communities for members’ mutual association and insurance (Lethbridge and Ng, 1982:202-3), can be conducive to Hong Kong’s labour unions in evolving a community-oriented role, suggesting, potentially, the work of a ‘third sector’ organisation’ on their agenda.

WHERE AREHONGKONG TRADE UNIONS DESTINED FOR? A GLIMPSE

OF THEIR PROSPECTS AS‘THIRD SECTOR’ ORGANISATIONS

There is a propensity for Hong Kong’s trade unions to develop and evolve into ‘community unionism’ as a new form of ‘third sector’ organisation. This can be shown by a number of endemic and contextual factors which are summarised below.

the ‘third sector’ domain at a time when these agencies are expected to have a widened scope in Hong Kong (Tung 2000. p. 33, para. 98).

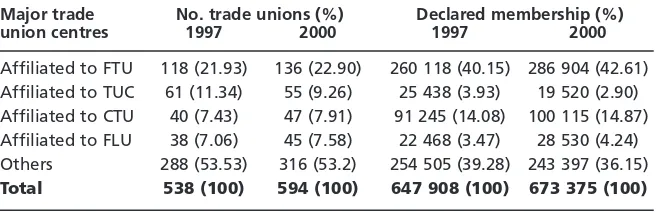

Empirical evidence: Preliminary note

As exploratory studies, two case studies mirroring such a possible new trend of Hong Kong unionism were conducted by the authors during winter 2000 and spring 2001. Because the present paper has not drawn its Hong Kong data from a representative sample survey of statistical vigour, it is beyond its scope to ascertain exactly the typicality of the above evolutionary tendency towards ‘community unionism’ among labour unions here. However, there are grounds to believe that the case studies are indicative of the pervasiveness of this type of trend in the development of unions. This is because one of the organisations studied was the leading trade union centre within the labour movement, the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (FTU), with affiliate unions organis-ing approximately 40 per cent of the unionised population in Hong Kong (see Table 2). The other organisation examined in this series was a ‘fundamental’ grass-roots labour body, which confined the spatial scope of its activities to a local district. A narrative each of these two cases is given below.

Case A: Established ‘lead’ trade union centre

A ‘benchmark’ example adopted in the study was the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (FTU)––the largest and leading centre of trade unions within the Hong Kong SAR. It now combines under its umbrella more than 150 affiliate unions, along with a number of functional committees and essentially semi-autonomous subsidiary business units. The data presented here were derived from a number of intensive interviews with a senior official of the Federation and his research department staff.1

‘THIRDWAY’ FORTRADEUNIONISM INHONGKONG? 385

Table 2 Declared membership of major (employee) trade union centres in Hong Kong, 1997 and 2000

Major trade No. trade unions (%) Declared membership (%) union centres 1997 2000 1997 2000

Affiliated to FTU 118 (21.93) 136 (22.90) 260 118 (40.15) 286 904 (42.61)

Affiliated to TUC 61 (11.34) 55 (9.26) 25 438 (3.93) 19 520 (2.90)

Affiliated to CTU 40 (7.43) 47 (7.91) 91 245 (14.08) 100 115 (14.87)

Affiliated to FLU 38 (7.06) 45 (7.58) 22 468 (3.47) 28 530 (4.24)

Others 288 (53.53) 316 (53.2) 254 505 (39.28) 243 397 (36.15)

Total 538 (100) 594 (100) 647 908 (100) 673 375 (100)

Source:Annual Statistical Report, Registry of Trade Unions, Labour Department, Hong Kong SAR Government, various issues.

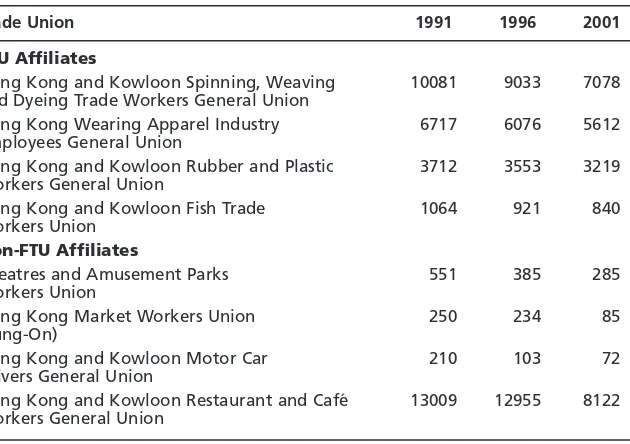

A number of interrelated policy themes were pervasive in the Federation’s agenda of post-1997 adjustments, apparently for dealing with the new politico-economic ‘paradigm’ arising from the politics of Hong Kong becoming part of China, and the economic integration of this ‘post-industrial’ city with the main-land ‘marketised’ socialist system. First, the trade union centre began assuming the ‘transmission-belt’ function as a quasi-political party of the working class, evidently after 1997 in Hong Kong as China’s SAR. As a group, it was anxious to penetrate the neighbourhood community to gain access to the labouring mass at a grass-roots level. Second, there was also an attempt by the labour federation to organise the local community and address the organisational problem caused by the en masse migration of Hong Kong factories north across the border. The exodus of Hong Kong’s manufacturing plants and their relocation in the mainland, almost epidemic after the mid-1980s, disrupted and purged the Federation of its traditional base of shopfloor organisation. See Table 3 for a profile of declining membership among some of the veteran industrial and occupational unions affiliated to the FTU. The Federation was also keen to compensate for this membership attrition by opening up new avenues of enlisting new members, such as contacting and organising them at the neighbourhood level.

The steady shift of the Federation’s attention in its membership maintenance and liaison work, away from the workplace level to that of the residential

Table 3 Declining membership among some of the veteran industrial and occupational

unions affiliated to the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (FTU)

Trade Union 1991 1996 2001

FTU Affiliates

Hong Kong and Kowloon Spinning, Weaving 10081 9033 7078

and Dyeing Trade Workers General Union

Hong Kong Wearing Apparel Industry 6717 6076 5612

Employees General Union

Hong Kong and Kowloon Rubber and Plastic 3712 3553 3219

Workers General Union

Hong Kong and Kowloon Fish Trade 1064 921 840

Workers Union Non-FTU Affiliates

Theatres and Amusement Parks 551 385 285

Workers Union

Hong Kong Market Workers Union 250 234 85

(Tung-On)

Hong Kong and Kowloon Motor Car 210 103 72

Drivers General Union

Hong Kong and Kowloon Restaurant and Café 13009 12955 8122

Workers General Union

neighbourhood, was also explained by other factors endemic to the changing labour market and employment structure. These were, as noted earlier, the growing size and importance of the white-collar service workers in constituting union membership. And yet, they were less amenable to organisation at the workplace level because of the nature of their work and mobility, and the re-casualisation of an enlarging segment of the labour force, who became self-employed, temporary employees and even part-timers without a full-time job and a stable place of work and employment, hence, lacking permanent attachment to any specific workplace.

In its search for a widened labour agenda devolved to the neighbourhood community, the trade union centre has probably retreated even more from collective bargaining activities, which have always been of peripheral concern for most of its affiliates except for a few trades (e.g. air cargo transport and public buses and stevedoring), and are still strongly organised at either the occupational or workplace level. In fact, the Federation was lukewarm about the notion of legislating on collective bargaining rights. Although it pledged nominal support for the pre-1997 collective bargaining and consultation law, which the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions (a rival union centre allied to the democrats) and other pro-democratic labour activists pushed through the Legislative Council on the eve of the political hand-over, it has never been keen on reviving and reinstating this enactment after its abrogation by the SAR provisional legislature shortly after the change of government (Fosh et al.2000, pp. 429–32, 439–42; see also Ng 2001, pp. 148–50).

Later, the recession during the closing years of the last century, alongside waves of lay-offs, retrenchment and pay cuts, would have afforded a ‘high-tide’ oppor-tunity for the trade union centre and its industrial arm to forge and establish ‘bridgeheads’ of collective bargaining and industrial consultation arrangements at the workplace level, especially among afflicted trades like retail services and restaurants. However, as events attested later, workplace industrial militancy around this period was largely feeble. Even where labour protests were organised by the unions, the actions were typically transient, ad hoc and enterprise-specific, hardly enduring beyond the spatial and time confinement of the dispute itself. The learning experiences accumulated from these labour struggles for enriching the labour unions’ collective bargaining capabilities were, therefore, limited.

mass to turn out at election (implicitly, the SAR government has viewed the voters’ turnout rate as a vicarious indicator of its level of legitimacy and popu-larity), as well as campaigning for candidates either nominated directly or sponsored by the Federation.

Active participation in the SAR elections and support of the pre-ballot cam-paigns were heralded as patriotic acts, inasmuch as the ‘proven’ performance of these PRC sanctioned electoral arrangements would attest to the SAR’s democratic advances towards maturity (Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions, 1997, pp. 27–28). Such an experience would nurture and buttress the success of the motherland’s ‘one country–two systems’ model prescription for achieving re-unification of the nation (Ng 1997, p. 671). Another key aspect of the ‘transmission-belt’ functions of these district offices was to promote and propagate the Basic Law and its provisions through a plurality of media channels. This department also organised a host of workshops and seminars to help educate the Federation’s membership and the residential neighbourhood served by the district offices in a variety of current affairs, including understanding the

Basic Law. This type of ‘transmission belt’ activity was deemed effective for enhancing an altruistic awareness and a feeling of belonging to Hong Kong and China felt at the grass-roots level, especially among local workers and labour unionists.

The above activities of community penetration are reminiscent of the quasi-political functions of socialist unions to act as a ‘transmission-belt’, and an organ of the state and the ruling political party for mass organisation/mobilisation. This mission would have probably remained masked and emasculated for a combined Hong Kong trade union like the FTU, were it not for the pre-1997 electoral reforms which enshrined the labour unions in a new ‘realm’ of power as the repres-entative agencies of the labour constituency (Hong Kong Government 1984; Ng 1986, 1997). Its ascendancy in political status, alongside the 1997 political reunification, has placed the Federation in an ambassadorial role to liaise with the Hong Kong compatriots at the grass-roots level for their participation and involvement in a patriotic cause, which was to support and ensure the success of the ‘one country–two systems’ experiment (Turner et al. 1991, pp. 101–2).

The notion of ‘community-based’ unionism was also consistent with the move of the Federation and its affiliates towards the model of ‘instrumental collectivism’. They, therefore, acted as providers of union services to their membership ‘clientele’. This led the trade union centre to re-structure the delivery of membership services, notably those of worker education (especially relating to labour law awareness and knowledge) as well as grievance advice, consulting and assistance, which has devolved to the grass-roots level of the neighbourhood community. Where these normal service ‘goods’ became available at the district offices, it was no longer necessary for union members to approach the regular union office at either headquarters or branch for consultation.

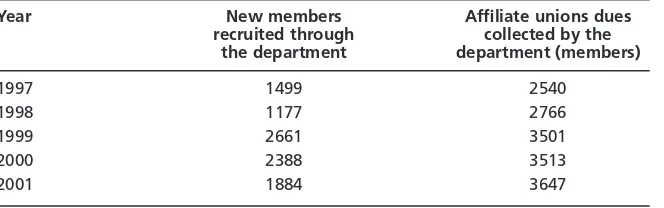

members. Concomitantly, these offices of community and district work also became the liaison points with the rank-and-file members, acting in a shop-steward-like role and collecting dues from union members. Table 4 summarises the progress of such membership liaison work achieved by the department during 1997–2000. The conspicuous growth of this kind of membership liaison work also signalled a new strategy by the Federation to organise and penetrate the neighbourhood community, particularly as an answer to the erosion of the affiliate unions’ regular liaison work at the workplace level.

The Federation believed that by penetrating the neighbourhood community, they would plant a web of ‘catchment areas’ to facilitate access to present and potential members who were now less accessible through their place of employment. This was largely due to the changing nature and fluidity of industry, employing organisations and the labour market. People could change jobs, as well as their trade skills and occupations. Moreover, it was less easy than before to identify a specific occupation to which an individual belonged, inasmuch as they were part-time workers holding concurrent (part-time) jobs across different trades. Even industry, occupation and craft-based unions have become elusive as bastions of the Federation’s affiliate support, to the extent that old skills, trades and industries (especially production ones) were withering away. The masked future of some of the veteran industrial unions within the FTU family and the emasculation of workplace level union organisation have, therefore, induced and even forced a reluctant Federation to reposition its union membership policy and the recruitment strategy of its affiliate unions.

Case B: Grass-roots level labour organisation

The second case was a quasi-union in a community named the Alliance (The Workers’ Rights Alliance), which was an emerging ‘vanguard’ organisation that pledged to serve and advance the industrial interests of a local community-based working population.2It lacked, however, the organisational sophistication and functional formality of the FTU, as noted earlier. Established in mid-1999 and focussing its mission and work activities upon a single district, Tsuen Wan, it was much smaller than the Federation in terms of breadth of service,

‘THIRDWAY’ FORTRADEUNIONISM INHONGKONG? 389

Table 4 Membership liaison work of the community and district services department

of the Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions

Year New members Affiliate unions dues recruited through collected by the

the department department (members)

1997 1499 2540

1998 1177 2766

1999 2661 3501

2000 2388 3513

2001 1884 3647

membership size and resourcefulness in key aspects like finance and manpower that command public attention and political influence. However, being struc-turally fluid and free from the historical bonds and biases borne by the Federation, the Alliance enjoyed a ‘lean’ advantage as a new brand of labour organisation.

Partly supported by Oxfam Hong Kong, the Alliance depended for its manpower substantially on the services rendered by a ‘core’ group of voluntary workers. There was no ‘formal’ registration of its members, as participants and leaders were all lay-workers. Spatially, Tsuen Wan, the district where the Alliance was located, was one of the established ‘vanguard’ industrial areas of Hong Kong. It was worn and reshaped by the rapid relocation of its factories and workshops to the mainland during the last two decades. Manufacturing works in Tsuen Wan has, therefore, largely withered away, and been steadily replaced by service and retail businesses that employ far fewer workers. The community is now flooded with middle-aged unemployed, low-income workers, under-employed part-timers and jobless new immigrants from the mainland. It was towards this marginalised ‘fringe’ of the industrially deprived in the grass-roots neighourhood community of Tsuen Wan that the Alliance has directed and targeted its services.

A proactive approach was pursued by this ‘community’ union. The Alliance organised ‘outreach’ activities, such as distributing promotional leaflets to workers outside the Labour Department and conducting regular ‘on-the-street’ education and poster sessions at two ‘habitual’ spots in Tsuen Wan. The objective was to furnish a kind of ‘face-to-face’ contact and ‘on the spot’ consultation service to the workers. This was usually followed by an individualised package of assistance. When needed, the ‘client’ workers were accompanied by the Alliance’s organisers to pursue their workplace grievances and assist in activities such as job search, job application letter-writing, job interviews, and visiting the Labour Department and the Labour Tribunals for lodging complaints and claims. This extensive and personalised array of services was backed by home visits to the workers and their families, and the provision of a 24-hour hot-line service. As a part of the Alliance’s efforts to promote a sense of ‘neighbourhood community’ among the workers, a ‘self-help’ programme was also launched whereby unemployed workers were coached and encouraged to offer mutual assistance to each other and help organise the activities of the Alliance.

the common labour market and employment interests of the working people belonging to the local ‘constituency’ of Tsuen Wan. However, this labour body has been increasingly perceived by some apprehensive unions in the ‘main-stream’ labour movement as an ‘aberrant’ entity which usurps the conventional activities of established unionism. Future competition from these hostile veteran organisations could be problematic for the Alliance.

CHALLENGE OF POST-INDUSTRIAL URBANISM AND ROLE OF LABOUR UNIONS AS‘THIRD SECTOR’ ORGANISATIONS

Limitation of the workplace ‘nexus’

The Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions and its affiliates portrayed in this paper explore an ‘experimental’ approach to building a new and alternative membership base anchored in the neighbourhood community. This appears to be a new membership strategy largely because of growing difficulties which these unions have experienced in organising the workplace.

The shopfloor ‘nexus’ of union organisation recedes today as a result of the changing character of work and employment, the most noticeable manifestation being the rise of ‘atypical employment’ in areas such as part-time and temporary hiring. These new forms of employment, coupled with the rise of self-employment in industries like transport, stevedoring, hospitality and entertainment, mean that the wage or fee-earner does not have an employer or lacks a fixed employer. To the labour unions, these new employment groups are far less amenable to membership recruitment, an exercise which needs to be extended beyond the ‘domain’ of the workplace. The latter has now become less relevant as an employing unit for casual and atypical employees.

Needs of the neighbourhood community

Also endemic to the process of ‘post-modern’ urban development are a series of ‘disorganisation’ and ‘fragmentation’ tendencies that threaten to rupture neighbourhood-based communities (Giddens 1991, pp. 198–9).

As a new ‘risk society’, the post-industrial neighbourhood poses an equally strong demand for collective agencies of community hedging as its traditional pre-industrial counterpart (Giddens 1991, pp. 28, 128). Such a role was performed by the occupational guild fraternity during the pre-industrial period of basic craft production. Later, in the heydays of the factory system, social work voluntary organisations also excelled as key agencies of community integration and stabilis-ation. However, as the domain of work and the institution of the workplace change in their nature, and decline in relevance to the central life interests of the working (and labouring) individuals in an era of ‘late modernity’, these conven-tional agencies of community integration are emasculated and are no longer adequate. In the post-modern context of the withering away of existent arrange-ments and institutions, new agencies are required. An example is a community-oriented labour body that can act as a ‘third sector’ socio-industrial agency, catering to those who have entered or are about to enter the waged labour market––even retired persons living on a hybrid of private and social wages, the pension and provident fund (Bacharach et al.2001; Mann 1998; Gapasin et al.

1998).

Socio-economic risks also exist in Hong Kong’s ‘post-industrial’ young urban society. In particular, the political transition of Hong Kong, the industrial drama of China’s modernisation reforms, and the East Asian financial crisis and post-crisis recession, combined to precipitate a series of new social and industrial issues in the past decades and the present. Many of these problems are associ-ated with the labour market interests, work and employment of the urban population, especially among those located at the periphery of the labour economy (Moody 1997, p. 282–92). Examples of these issues are the insecurity of part-time and flexi-employment, staggering unemployment levels, low wages and long hours of those labouring on the ‘fringe’ of the waged labour economy, business consolidation and personnel down-sizing, involuntary self-employment and retirement, foreign worker importation, de-skilling and problematic retraining, and a trendy stampede for expensive adult education in the search for competency, knowledge enhancement and credential layering. These issues constitute a new ‘risk syndrome’ for Hong Kong and will pose a pressing case for an agenda of effective action from the government and organised labour. To perform such a role, labour unions can be destined as a potentially ‘third sector’ agency for pursuing a social strategy of the ‘third way’.

CONCLUSION

We suggest, based upon our Hong Kong data, that there is the potential for trade unions, which are still largely workplace oriented, to restructure themselves and perform the role of community unions in response to these socio-industrial challenges of late urbanism. As an echo to Giddens’ ‘third way’ thesis, the future unions assuming such a community role, can be located within the ‘third sector’, outside the state and private business domains, as well as outside the conventional ambit of any specific trades, industries or occupations.

There are, of course, problems associated with attempts to create (and re-create) a union-focused community outside the occupation. If unionisation were to be based upon organisation of the neighbourhood community, community unions will lack collective awareness due to a lack of common occupational interest and identity. Instead, they could be fragmented into an ‘enclave’ of a localised working people’s combination. These ‘combines’ are occupationally and industrially mixed, and are pluralistic, yet isolated and segregated spatially from each other. For this reason, the model of a ‘community union’ as a ‘third sector’ agency will be open to problems of internal organisation and integration because it lacks the workplace ‘nexus’ of conventional unionism. Hence, it is clearly premature to predict the future pervasiveness of this new form of ‘community unionism’ within the Hong Kong labour movement. As it appears, it may take years for it to crystallise into a shape that can actually eclipse the ‘mainstream’ union tradition as an effective alternative in the ‘post-modern’ age.

ENDNOTES

2. The profile on the Alliance was largely based upon data that we collected from a series of open-ended, unstructured interviews conducted with the Executive Secretary of the Alliance during February and March 2001. We were also able to supplement the profile with information drawn from pamphlets published by the Alliance promoting its work activities and programs.

REFERENCES

Bacharach SB, Bamberger PA, Sonnenstuhl WJ (2001) Mutual Aid and Union Renewal: Cycles of Logics of Action. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Brown W, Marginson P, Walsh J (1995) Pay determination and collective bargaining. In: Edward PK, eds, Industrial Relations: Theory and Practice in Britain, pp. 123–50. Oxford: Blackwell. Chan MHY, Ng SH, Ho EYY (2000) Labour and Employment.In: Ng SH, Lethbridge DG, eds,

The Business Environment in Hong Kong, 4th edn, pp. 74–96, Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Dore R (1990) British Factory-Japanese Factory,1990 edition with a new afterward by the author, Berkeley: University of California Press.

England J, Rear J (1981) Industrial Relations and Law in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Fosh P, Carver A, Chow Wilson WS, Ng SH, Samuels H (2000) Trade Unions and Their relation-ship to power in Hong Kong. The Journal of Industrial Relations42 (3), pp. 417–44.

Gapasin F, Yates M (1998) Organising the unorganised: Will promises become practices? In: Wood E, Meiksins P, Yates M, eds, Rising From the Ashes? Labour in the Age of ‘Global’ Capitalism. New York: Monthly Review Press, pp. 73–86.

Giddens A (1991) Modernity and Self-Identity, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Giddens A (1998) The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press. Giddens A (2000) The Third Way and its Critics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions (1997)1994–97 Report. Hong Kong: The Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions.

Hong Kong Government (1984) The Further Development of Representative Government in Hong Kong.

Hyman R (1994) Introduction: Economic restructuring, market liberalism and the future of national industrial relations systems. In: Hyman R, and Ferner A, eds, New Frontiers in European Industrial Relations, pp.1-14. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lethbridge D, Ng SH (1982) Hong Kong. A monograph in the series edited by Blanpain P,

International Encyclopaedia for Labour Law and Industrial Relations, ELL (suppl. 25), The Netherlands: Kluwer.

Mann E (1998) Class, community, and empire. In: Wood E, Meiksins P, Yates M, eds, Rising From the Ashes? Labour in the Age of ‘Global’ Capitalism, pp. 100–9. New York: Monthly Review Press. Marginson P, Sisson K (1990) Single table talk. Personnel Management. May 1990, pp. 46–9. Moody K (1997) Workers in a Lean World: Unions in the International Economy. London: Verso. Ng SH (1986) Labour. In: Cheung YS, ed,Hong Kong in Transition. pp. 268–99. Hong Kong: Oxford

University Press.

Ng SH (1997) Reversion to China: Implications for labour in Hong Kong. International Journal of Human Resource Management8 (5), 660–70.

Ng SH (1998) Postscript: Hong Kong at the dawn of a new era. in Ng SH, Lethbridge DG, eds,

The Business Environment in Hong Kong, 3rd edition with a post-handover postscript on the Hong Kong SAR, pp. 212–32. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

Ng SH (2001) Hong Kong labour law in retrospect. In: Lee PT, ed., Hong Kong Reintegration with China: Political, Cultural and Social Dimensions, pp. 129–55. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Ng SH, Rowley C (1997) At the Break of Dawn? Hong Kong industrial relations and prospects under its political transition. Asia Pacific Business Review4 (1), 83–96.

Ng SH, Warner M (1998) China’s Trade Unions and Management. London: Macmillan.

Olney SL (1996) Unions in A Changing World: Problems and Prospects in Selected Industrialized countries. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Roberts BC (1964) Labour in the Tropical Territories of the Commonwealth. London: The London School of Economics and Political Science.

Sisson K, Storey J (2000) The Realties of Human Resource Management: Managing the Employment Relationship. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Storey J, Sisson K (1993) Managing Human Resources and Industrial Relations. Buckingham: Open University.

Thurley K (1983) The Role of Labour Administration in Industrial Society. In: Ng SH, Levin DA, eds, Contemporary Issues in Hong Kong Labour Relations, pp. 106–20. Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong.

Thurley K (1988) Trade Unionism in Asian Countries. In: Jao YC, Levin DA, Ng SH, Sinn E, eds, Labour Movement in a Changing Society: The Experience of Hong Kong,pp. 24–31. Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong.

Tung CH (2000) Serving the Community, Sharing Common Goals. Annual policy address by the Chief Executive at the Legislative Council, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Hong Kong: Printing Department, Hong Kong SAR Government.

Turner HA, Fosh P, Gardner M, Hart K, Morris R, Ng SH, Quinlan M, Yerbury D (1980) The Last Colony: But Whose? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Turner HA, Fosh Patricia, Ng SH (1991) Between Two Societies: Hong Kong Labour in Transition. Hong Kong: Centre of Asian Studies, University of Hong Kong.