Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI

TANJUNGPINANG, KEPULAUAN RIAU] Date: 12 January 2016, At: 17:50

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Validating the Management Education by

Internet Readiness (MEBIR) Scale With Samples of

American, Chinese, and Mexican Students

John A. Parnell & Shawn Carraher

To cite this article: John A. Parnell & Shawn Carraher (2005) Validating the Management Education by Internet Readiness (MEBIR) Scale With Samples of American, Chinese, and

Mexican Students, Journal of Education for Business, 81:1, 47-54, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.1.47-54 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.1.47-54

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 19

View related articles

ABSTRACT. In this study, the

authors validated a scale that measures

Management Education by Internet

Readiness (MEBIR) using American,

Chinese, and Mexican students. The

authors analyzed scale properties as

well as prospects for Internet-delivered

management education programs in

China and Mexico. Findings supported

the integrity of the original scale and

its distinction from one’s

self-manage-ment ability. The MEBIR scale

repre-sents a good first step toward a

stan-dardized assessment and identification

of those most likely to benefit from

Internet-mediated education and

train-ing efforts.

Validating the Management Education

by Internet Readiness (MEBIR) Scale

With Samples of American, Chinese,

and Mexican Students

JOHN A. PARNELL SHAWN CARRAHER

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT PEMBROKE CAMERON UNIVERSITY

PEMBROKE, NORTH CAROLINA LAWTON, OKLAHOMA

number of corporate experts believe that, within several years, the majority of all corporate training will be delivered online (Herther, 1997). In addition, the number of busi-ness schools offering programs over the Internet continues to expand (Arbaugh, 2000; Kwartler, 1998). However, online delivery of undergrad-uate and gradundergrad-uate business courses remains a relatively recent phenome-non, with a small, but growing litera-ture base of knowledge (Briones, 1999; Clauson, 1999; Ellram & Easton, 1999; Taylor, 1996). This is true in the global business arena, although the use of online instruction is growing rapidly (Smith & Duus, 2001). Nonetheless, there still exists no coherent theory of Internet management education (Simonson, Schlosser, & Hanson, 1999) because most conceptual work has been either macrotheoretical (White, Rea, McHaney, & Sanchez, 1998) or atheoretical (Hiltz & Well-man, 1997).

Traditional universities have been focused primarily on training faculty to develop courses, although relatively little interest has been shown in ascer-taining student readiness for these courses (Robertson & Stanforth, 1999). In a previous study (2003), we proposed the Management Education by Internet Readiness (MEBIR) scale to measure a learner’s propensity for successfully completing a manage-ment education experience delivered

through the Web. Initial empirical results were promising, but further val-idation of the scale was required.

Meanwhile, Internet delivery in the international arena appears to be grow-ing exponentially, but remains in its nascent stage of development. In other words, demand for the Internet is so great that many providers are entering the market early and with limited resources. As a result, they have experi-enced difficulties along the way. The use of the Internet to address the tremendous international demand for management education may be an attractive means of meeting the interna-tional challenge. Following this logic, in the present study, we assessed scale properties among American, Chinese, and Mexican samples. We also analyzed the data for prescriptive purposes.

Online Delivery of Management Education and the Management Education by Internet Readiness (MEBIR) Scale

A variety of factors have led to the recent trend toward Internet-based man-agement education (Klor de Alva, 2000; MacFarland, 1998). Internet access in the United States has expanded geometrical-ly while advances in course platforms and computing capacity have created opportunities for the efficient delivery of sophisticated content via the Web (Alavi, Yoo, & Vogel, 1997; Holland, 1996; Par-nell & Carraher, 2003). Competition

A

from nonacademic sources (e.g., corpo-rate universities) has intensified (Dunn, 2000; Kedia & Harveston, 1998; Moore, 1997; Rahm & Reed, 1997; Shrivastava, 1999). Many learners are reporting high satisfaction with the online delivery of management education (Bailey & Cotlar, 1994; Brandon & Hollingshead, 1999; Ellram & Easton, 1999; Greco, 1999; Kerker, 2001; Parnell, 2000; Sweeney & Oram, 1992).

In some respects, the attractiveness of the Internet as a delivery tool is enroll-ment driven. Enrollenroll-ments in traditional Master’s in Business Administration (MBA) programs have not experienced consistent growth throughout the past decade (MacLellan & Dobson, 1997). The Internet has facilitated the delivery of content in a more convenient manner, resulting in a potential increase in online MBA offerings (Greco, 1999). Indeed, student satisfaction data suggest that the implementation of distance pro-grams is easier to effectuate at the grad-uate level than at the undergradgrad-uate level (Clow, 1999).

There is considerable anecdotal evi-dence to support the notion that online delivery has the potential to be at least as effective as traditional face-to-face delivery due to a number of advantages inherent in the delivery method (Meisel & Marx, 1999). These advantages include flexibility and convenience (Nelson, 1997; Oblinger & Kidwell, 2000), increased access for isolated learners (Nelson, 1997; Ross & Klug, 1999), the Internet’s plethora of busi-ness and academic resources (Bigelow, 1999; Freitas, Myers, & Avtgis, 1998; Quick & Lieb, 2000; Strauss, 1996), and potential for improved delivery effi-ciency (Roberts, 1998).

There are a number of avenues for criticism of online instruction (Parnell & Carraher, 2003). Critics charge that much is lost when instructors and learners are not face-to-face and able to ask questions freely and discuss issues (Smith & Dillon, 1999) and that testing over the Internet is cumber-some and creates numerous opportuni-ties for academic dishonesty. They also argue that the actual long run costs associated with distance education can be tremendous (Parnell, 2000), espe-cially for a technology whose

educa-tional value is not yet fully understood (Grossman, 1999).

The Management Education by Internet Readiness (MEBIR) Scale

The advantages and disadvantages of Internet-mediated management edu-cation notwithstanding, individual learner characteristics represent a crit-ical factor in the success of such pro-grams (Hara, 1998). The MEBIR scale (see Appendix) was developed on the philosophy that individual characteris-tics—not just technology, faculty abil-ity, and content—should be assessed before launching an Internet-delivered management education program.

The first dimension of the scale, technological mastery (TECH), reflects the learner’s familiarity with and mastery of the medium by which online management content is deliv-ered, which is the Internet (El-Tigi, 2000; Hara, 1998; Mioduser, Nach-mias, Lahav, & Oren, 2000; Parasura-man, 2000; Rennes & Collis, 1998). The second dimension, flexibility of course delivery (FLEX), reflects the degree to which the learner perceives that Internet-delivered coursework is more flexible and convenient (Ellis, 2000; Galer, 1999; Mioduser et al.; Rich, Pitman, & Gosper, 2000; Tysome, 2001). The final dimension, anticipated quality of course (QUAL), reflects the degree to which the learner perceives Internet courses would be of high quality (Blake, 2000; Dellana, Collins, & West, 2000; Kolb, 2000; Parasuraman & Grewal, 2000).

The Internet in China and Mexico

The Internet in China

According to one survey, there are approximately 10 million personal computers with access to the Internet and a total of 26.5 million Internet users in China (“China,” 2005). The number of Internet users in China has nearly doubled every 6 months for the past 2 years (Zhao, 2002). However, reliable usage data are not presently available (Ashling, 2005).

Most Chinese Internet activity has been for e-mail and informational

pur-poses. Although three fourths of Chi-nese online users report spending time at e-commerce Web sites, most have never made an online purchase. Indeed, using the Internet as a pur-chase tool runs counter to traditional Chinese shopping habits. Although their Internet experience is limited, Chinese cyberbuyers reported an inter-est in and willingness to expand the online purchase activity in the coming months (Wee & Ramachandra, 2000). However, most analysts believe that online buying will become mainstream within the next few years, and expect the strong growth in Internet usage to continue (“China”).

The Chinese government is a strong supporter of Internet usage. Most gov-ernment agencies have Web pages, although they primarily provide infor-mation and are not used to conduct busi-ness. State-owned China Telecom has reduced its Internet access fees consid-erably since 1997 (Hachigian, 2001).

The Chinese government is sensitive to the use of the Internet as an effective medium of state opposition (Yang, 2001). Net executives in China seek to adhere to local customs, a practice that many critics interpret as voluntary cen-sorship. For example, the Web site for Yahoo in China posts news on world events only from government-owned newspapers. A number of international news sites are often blocked at central-ized routers that control Internet traffic in and out of China, resulting in hit-and-miss access for savvy surfers who read English (Yee, 2001).

Internet advertising is a relatively new phenomenon in China. In 2000, the Chinese government issued its first licenses to local Internet companies, effectively establishing a market-entry criterion for Internet companies that wish to display advertisements on their sites. Internet advertising in China was expected to reach $250 million by 2004 (Madden, 2000). China Southern Air-lines boasts one of the most successful sales-producing Web sites in China, with sales topping $50 million annually (China Southern Airlines, 2000).

The adoption rate of the Internet as a purchasing tool in China lags behind other parts of Asia, such as Hong Kong and Singapore. The typical Chinese

cyberbuyer is less than 30 years old, earns less than $2,400 per year, makes online purchases of less than $100, and is mostly likely to be a male management or technical professional with higher edu-cational levels (“China,” 2005; Wee & Ramachandra, 2000).

The Internet in Mexico

Internet usage in Mexico remains concentrated in the hands of a few (Gower, 2001b). Recently, however, free Internet access has been touted as a means of bridging the digital divide in Mexico. Nonetheless, estimates suggest that only about 5% of the Internet con-nections in Mexico are made through free-access providers, compared to about 50% in Europe (Gower, 2001a). Poor reliability and the lack of technical support have been identified as major problems associated with the effort.

Internet advertising was expected to grow more rapidly in Latin America than any other major online region between 2001 and 2005 (Mack, 2001). A number of key Mexican firms, including Grupo Bimbo, Grupo Posadas, and Telmexare, are fast developing their Internet infra-structures (“Top 10,” 2001). Financial institutions in Mexico have been slow to adapt to the Web, but this appears to be changing (Thurston, 2000).

In sum, the rapidly emerging economies of China and Mexico present opportunities for providers of Internet management education. However, Inter-net adoption in the two countries lags behind the United States. There are sub-stantial differences between China and Mexico in terms of Internet usage pat-terns, cultural influences, and govern-mental regulations.

Validation of the Management Education by Internet Readiness (MEBIR) Scale

We administered the MEBIR scale to 145 American, 139 Chinese, and 113 Mexican management students. The sample included Chinese students in mainland China and those studying in the United States. We also asked respondents to complete a previously validated three-item self-management scale (Parnell & Carraher, 2003) and to

provide age and undergraduate grade point average (GPA) information.

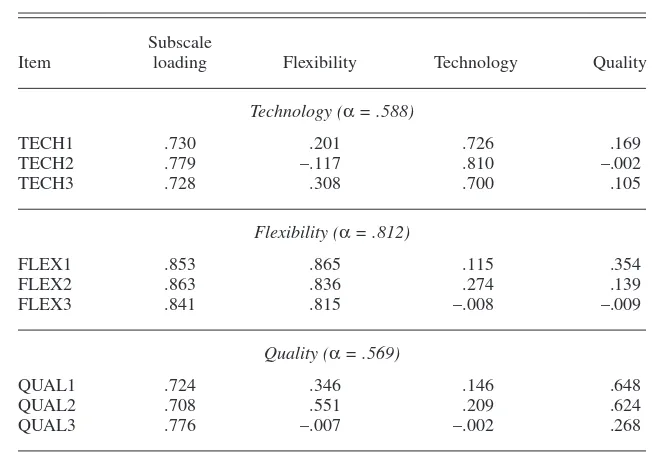

We assessed reliability and validity to ensure the integrity of the MEBIR scale. For the American sample (see Table 1), coefficient alpha (Cronbach, 1951) reli-ability estimates for the subscales were .588 for the TECH scale, .812 for the FLEX scale, and .569 for the QUAL scale, and we found each to be unidi-mensional based on the results of limit-ed information factor analysis (Sethi & Carraher, 1993), a confirmatory factor analytic method for the estimation of unidimensionality. Hence, the scale has a moderate level of internal consistency, an important indication of reliability (Kuratko, Montagno, & Hornsby, 1990; Peter, 1979).

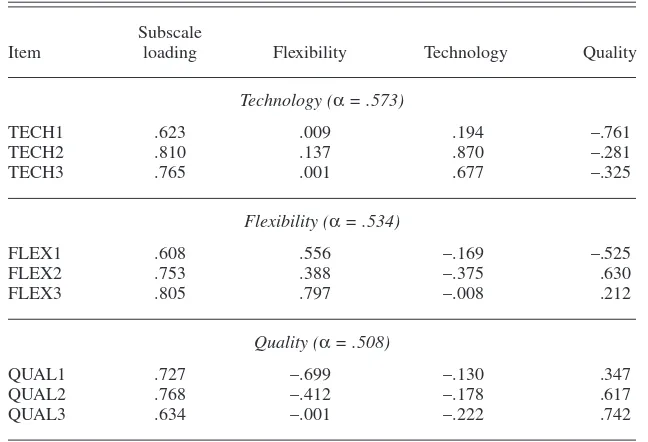

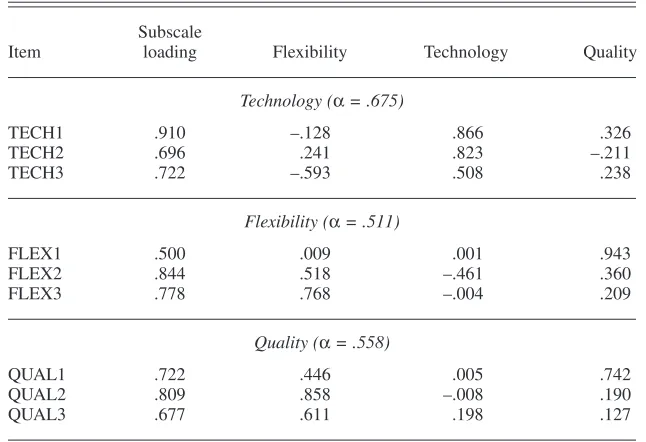

For the Chinese sample (see Table 2), Cronbach’s alpha reliability estimates for the subscales were .573 for the TECH scale, .534 for the FLEX scale, and .508 for the QUAL scale. For the Mexican sample (see Table 3), Cron-bach’s alpha reliability estimates for the subscales were .511 for the TECH scale, .558 for the FLEX scale, and .675 for the QUAL scale.

We assessed convergent and discrim-inant validity in three ways, first by cor-relation matrix (Bagozzi, 1981;

Buck-ley, Carraher, & Cote, 1992; Carraher, Buckley, & Cote, 2000; Carraher & Whitley, 1998). The matrix developed represents mean correlations among items from each scale separately and mean correlations between items from different scales. Intracorrelations within the MEBIR scale (items within the same subscales) were moderately high and consistent (.323 among TECH items, .394 among FLEX items, and .288 among QUAL items), suggesting con-vergent validity (Campbell & Fiske, 1959). The intercorrelations within the MEBIR scale (items within different subscales) were substantially lower and consistent (.052), suggesting discrimi-nant validity (Campbell & Fiske; Churchill, 1979).

Second, the convergence of the items on the factors demonstrated convergent validity of the scale. The “clean” load-ing of each item on only one factor sug-gested discriminant validity.

Finally, we assessed convergent and discriminant validity through the use of variance extracted and shared vari-ance statistics (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Variance extracted is the amount of the joint variance captured by the construct and not by measure-ment error. Fornell and Larcker

recom-TABLE 1. Rotated Factor Solution for the Management Education by Internet Readiness (MEBIR) Scale, U.S. Sample

Subscale

Item loading Flexibility Technology Quality

Technology (α= .588)

TECH1 .730 .201 .726 .169

TECH2 .779 –.117 .810 –.002

TECH3 .728 .308 .700 .105

Flexibility (α= .812)

FLEX1 .853 .865 .115 .354

FLEX2 .863 .836 .274 .139

FLEX3 .841 .815 –.008 –.009

Quality (α= .569)

QUAL1 .724 .346 .146 .648

QUAL2 .708 .551 .209 .624

QUAL3 .776 –.007 –.002 .268

Note. Technology refers to the Technological Mastery dimension of the MEBIR, Flexibility refers to the Flexibility of Course Delivery dimension, and Quality refers to the Anticipated Quality of Course dimension.

mended .50 as a benchmark for the establishment of convergent validity. Variance extracted was .534 for the TECH subscale, .610 for the FLEX subscale, and .528 for the QUAL sub-scale, suggesting some degree of con-vergence on the factors.

Shared variance is the squared correla-tion between two constructs and should be significantly less than the extracted variances for either of the constructs. Shared variance between the subscales averaged .039, suggesting discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

In sum, results of the analysis sup-ported the integrity of the scale. Further, there was also evidence to suggest that the scale can be applied to samples out-side of the United States, specifically those in Mexico and China.

Findings and Implications for Management Education

Given the support for the MEBIR scale, it is worthwhile to examine rela-tionships among the various subscales. It is also interesting to consider prospec-tive relationships between each subscale and the age and grade point averages (GPA) of the respondents. As such, fac-tor scores (regression method) were

cal-culated for each subscale, as well as for the three-item self-management scale (Parnell & Carraher, 2003).

Self-management ability was positive-ly correlated with each of the three MEBIR subscales (see Table 4). This is not surprising, and supports the impor-tance of an ability to organize effective-ly, manage one’s time, and maintain self-discipline (Hara, 1998; Meisel & Marx, 1999). Hence, one’s self-management ability can facilitate Internet-mediated education because it enables learners to adjust to the increased independence associated with online training.

It is interesting that older students tended to score higher on the self-man-agement (SELF) scale, but they were less likely to perceive Internet-mediat-ed instruction to be of high quality. Not having been raised with the tech-nology, many older students may remain convinced of the superiority of face-to-face instruction even when they possess adequate self-manage-ment skills.

Undergraduate GPA was not associ-ated with any of the MEBIR subscales, although respondents with higher GPAs were also likely to report higher self-management abilities. This find-ing is worth notfind-ing because it

high-lights the fact that neither GPA nor self-management ability necessarily heightens one’s readiness to use the Internet as a learning tool.

Three implications for management education are worthy of brief discus-sion. First, international management education delivered through the Inter-net presents an exceptional long-term opportunity for graduate institutions, as future students will likely possess greater comfort with technology than current ones (Bayram, 1999; March, 2000; Quilter & Chester, 2001). In addition, older learners tend to place higher value on the flexibility associat-ed with Internet delivery and to per-ceive their own self-management abil-ities to be higher (Parnell, 2000; Schwarzer, Mueller, & Greenglass, 1999). Hence, given the return of older students to higher education at an increasing rate, the value of a universi-ty offering its graduate business cours-es online should continue to increase as well. This could present a challenge, however, given the fact that older stu-dents may not perceive the quality of Internet-mediated instruction to be as high as that of traditional face-to-face instruction, as was the case with the present sample.

Second, face-to-face interactions provide a personal touch not easily secured in an online environment. Practitioners developing programs for international delivery should consider that at least some personal contact might be warranted (Hara, 1998). The scale developed in this article mea-sures readiness for Internet course-work, but makes no claims concerning its effectiveness. We would suggest that this scale be validated on other samples and also linked to other out-comes of interest to management edu-cators, such as retention rates, learn-ing, use of new skills on the job, and value added to the student and poten-tial employers.

Third, management education in China and, to a lesser extent, in Mexico, typically consists of hard, technically ori-ented management curricula delivered via lecture. A high degree of student par-ticipation during lectures is not common (Wo & Pounder, 2000), making the stu-dent acceptance of Internet education

TABLE 2. Rotated Factor Solution for the Management Education by Internet Readiness (MEBIR) Scale, Chinese Sample

Subscale

Item loading Flexibility Technology Quality

Technology (α= .573)

TECH1 .623 .009 .194 –.761

TECH2 .810 .137 .870 –.281

TECH3 .765 .001 .677 –.325

Flexibility (α= .534)

FLEX1 .608 .556 –.169 –.525

FLEX2 .753 .388 –.375 .630

FLEX3 .805 .797 –.008 .212

Quality (α= .508)

QUAL1 .727 –.699 –.130 .347

QUAL2 .768 –.412 –.178 .617

QUAL3 .634 –.001 –.222 .742

Note. Technology refers to the Technological Mastery dimension of the MEBIR, Flexibility refers to the Flexibility of Course Delivery dimension, and Quality refers to the Anticipated Quality of Course dimension.

potentially higher in China and Mexico than in the United States. Hence, the rela-tionship between self-management abili-ty and one’s readiness of Internet-mediat-ed Internet-mediat-education may not be as critical outside of the United States.

Future Directions

The present study lends support to the application of the MEBIR scale outside of the United States. A number of key questions remain, however, resulting in several important avenues for future

research. First, the application of West-ern scales to non-WestWest-ern samples remains a difficult process (Peng, Lu, Shenkar, & Wang, 2001), and the pres-ent study was no exception. When scales are not translated to account for language and cultural differences for generalization’s sake, scale reliabilities generally suffer as a result. However, when scales are translated or modified to address cultural differences, then direct comparisons between distinct cultural groups are tenuous at best. Some researchers have crafted and

implemented different measures for work values in China and in the United States, arguing that Western measures may not be appropriate within the Chi-nese culture (Cyr & Frost, 1991; Jamal, 1999, Siu, 2003; Xie, 1996). Solving this dilemma is not easy, however. Future research should embrace multi-ple approaches to develop a comprehen-sive understanding of the phenomena.

Second, Western models and instru-ments typically do not measure the con-straints in which Chinese employers function (Adler, Campbell, & Laurent, 1989). As a result, Chinese applications of Western survey instruments, such as the scales used in the present study, have their limitations. Alternatively, researchers may choose to develop instruments from indigenous Chinese values (e.g., Fahr, Podsakoff, & Cheng, 1987; Fahr, Tsui, Xin, & Cheng, 1998) to maximize measurement precision. Unfortunately, doing so is expensive and typically produces results that are incomparable with Western literature (Peng et al., 2001). Additional research that integrates both approaches in hypothesis testing may lend more robust and reliable conclusions.

Third, individual characteristics of the learner, although critical, represent only one factor that can influence the success or failure of Internet-mediated management education (Lo Choi Yuet Ngor, 2001; Parnell & Carraher, 2003; Quilter & Chester, 2001). This is espe-cially true when the content has an international flavor and learners are dis-persed across borders. Additional research should examine the relation-ships between MEBIR and other critical success factors, such as faculty training, faculty and learner technological access and support, cultural differences that may exist, and specific course content (Dobrin, 1999; Hitch & Hirsch, 2001). Delivery of courses via the Web also necessitates that faculty members “buy in” to a nontraditional model of educa-tion, whereby the faculty member becomes the facilitator instead of the teacher (Harden & Crosby, 2000).

Fourth, business schools must learn to target learners with the combination of individual characteristics most appropri-ate for their program offerings (Cox, 2000; Egerton, 2001). These

characteris-TABLE 3. Rotated Factor Solution for the Management Education by Internet Readiness (MEBIR) Scale, Mexican Sample

Subscale

Item loading Flexibility Technology Quality

Technology (α= .675)

TECH1 .910 –.128 .866 .326

TECH2 .696 .241 .823 –.211

TECH3 .722 –.593 .508 .238

Flexibility (α= .511)

FLEX1 .500 .009 .001 .943

FLEX2 .844 .518 –.461 .360

FLEX3 .778 .768 –.004 .209

Quality (α= .558)

QUAL1 .722 .446 .005 .742

QUAL2 .809 .858 –.008 .190

QUAL3 .677 .611 .198 .127

Note. Technology refers to the Technological Mastery dimension of the MEBIR, Flexibility refers to the Flexibility of Course Delivery dimension, and Quality refers to the Anticipated Quality of Course dimension.

TABLE 4. Correlation Matrix for Management Education by Internet Readiness (MEBIR) Scale, Self-Management Scale (SELF), Age, and Grade Point Average (GPA)

Item TECH FLEX QUAL SELF AGE GPA

TECH 1.000 –.015 –.044 .118* –.047 –.013* FLEX 1.000 .328* .232* –.057 .071 QUAL 1.000 .193* –.155* .068

SELF 1.000 .104* .195*

AGE 1.000 –.015

GPA 1.000

Note. TECH = Technological Mastery; FLEX = Flexibility of Course Delivery; QUAL = Antici-pated Quality of Course.

*p= .05.

tics include MEBIR, but may also include myriad personality factors and other factors, such as learning styles, cop-ing methods, tolerance for ambiguity, polychronicity, need for achievement, cognitive complexity, intelligence, and motivation to learn. The development of a comprehensive model depicting dimen-sions critical to success in various gradu-ate programs is needed rather than the use of a piecemeal approach to matching applicants with programs.

The final future direction concerns outcomes assessment. If the quality of Internet-mediated programs is to be eas-ily and effectively measured, it will be necessary to develop concise, opera-tional models for comparing outcomes from Internet-delivered and traditional programs. Traditional assessment mod-els assume face-to-face interaction between instruction and learner. As such, alternative models are necessary to account for differences inherent in Internet-mediated instruction, and tradi-tional models may need to be modified to account for different factors in the two instructional styles. This instrument provides a good first step toward the standardized assessment process and the identification of those ready to learn through Internet education.

REFERENCES

Adler, N., Campbell, N., & Laurent, A. (1989). In search of appropriate methodology: From out-side of the People’s Republic of China looking in. Journal of International Business Studies, 20, 61–74.

Alavi, M., Yoo, Y., & Vogel, D. R. (1997). Using information technology to add value to man-agement education. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 1310–1333.

Arbaugh, J. B. (2000). Virtual classroom charac-teristics and student satisfaction with Internet-based MBA courses. Journal of Management Education, 24(1), 32–54.

Ashling, J. (2005). Recent developments in China. Information Today, 22(4), 1–3.

Bagozzi, R. P. (1981). Attitudes, intentions, and behaviors: A test of some key hypotheses. Jour-nal of PersoJour-nality and Social Psychology, 41, 607–627.

Bailey, E. K., & Cotlar, M. (1994). Teaching via the Internet. Communication Education, 43, 184–193.

Bayram, S. (1999). Internet learning initiatives: How well do Turkish virtual classrooms work? THE Journal, 26(10), 65–69.

Bigelow, J. D. (1999). The Web as an organiza-tional behavior learning medium. Journal of Management Education, 23, 635–650. Blake, N. (2000). Tutors and students without

faces or places. Journal of Philosophy of Edu-cation, 34(1), 183–199.

Brandon, D. P., & Hollingshead, A. B. (1999). Collaborative learning and computer-supported groups. Communication Education, 48(2), 109–126.

Briones, M. G. (1999, March 29). E-commerce master’s programs set to explode. Marketing News, 33(7), 19.

Buckley, M., Carraher, S., & Cote, J. (1992). Mea-surement issues concerning the use of invento-ries of job satisfaction. Educational and Psy-chological Measurement, 52,529–542. Campbell, D. R., & Fiske, D. W. (1959).

Conver-gent and discriminant validation by the multi-trait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bul-letin, 56, 81–105.

Carraher, S., Buckley, M., & Cote, J. (2000). Strategic entrepreneurialism in analysis: Global problems in research. Global Business & Finance Review, 5, 77–86.

Carraher, S., & Whitely, W. (1998). Motivations for work and their influence on pay across six countries. Global Business & Finance Review, 3, 49–56.

China has 100 million Internet users. (2005, June 28). Xinhua. Retrieved June 28, 2005, from http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-06/28/ content_3150626.htm

China Southern Airlines. (2000, July 25). China Southern Airlines has #1 revenue producing Web site in China; Internet cargo sales top-ping $50M RMB per month. Retrieved August 30, 2005, from http://www.cs-air.com/en/news/ 2000/20000725/001.ASP Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for

develop-ing better measures of marketdevelop-ing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16, 64–73. Clauson, J. (1999). On-line quality courses offer

many side benefits. Quality Progress, 32(1), 83–89.

Clow, K. (1999). Interactive distance learning: Impact on student course evaluations. Journal of Marketing Education, 21, 97–105. Cox, G. (2000). Why I left a university Internet

education company. Change, 32(6), 12–19. Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the

internal structure of tests. Psychometrica, 16, 297–334.

Cyr, D., & Frost, P. (1991). Human resource man-agement practice in China: A future perspec-tive. Human Resource Management 30, 199–215.

Dellana, S., Collins, W., & West, D. (2000). On-line education in a management science course: Effectiveness and performance factors. Journal of Education for Business, 76(1), 43–48. Dobrin, J. (1999). Who’s teaching online. ITPE

News, 2(12), 6–7.

Dunn, S. L. (2000). The virtualizing of education. The Futurist, 34(2), 34–38.

Egerton, M. (2001). Mature graduates II: Occupa-tional attainment and the effects of social class. Oxford Review of Education, 27(2), 271–286. El-Tigi, M. (2000). Integrating WWW technology

into classroom teaching: College students’ per-spectives of course Web sites as an instruction-al resource. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY.

Ellis, K. (2000). A model class. Training, 37(12), 50–58.

Ellram, L. M., & Easton, L. (1999). Purchasing education on the Internet. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 35(1), 11–19.

Fahr, J. L., Podsakoff, P., & Cheng, B. S. (1987). Culture-free leadership effectiveness versus moderators of leadership behavior: An exten-sion and test of Kerr and Jermier’s substitutes for leadership model in Taiwan. Journal of

International Business Studies, 18, 43–60. Fahr, J. L., Tsui, A., Xin, K., & Cheng, B. S.

(1998). The influence of relational demography and Guanxi: The Chinese case. Organization Science, 9, 471–488.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50.

Freitas, F. A., Myers, S. A., & Avtgis, T. A. (1998). Student perceptions of instructor immediacy in conventional and distributed learning class-rooms. Communication Education, 42, 366–372.

Galer, S. (1999). Distance learning the high-tech way. Computing Japan, 6(8), 30–35.

Gower, M. (2001a). Down, but not out: Mexico’s free ISPs. Business Mexico, 11(2), 48. Gower, M. (2001b). Web of poverty: Why the

dig-ital divide matters. Business Mexico, 11(4), 55. Greco, J. (1999). Going the distance for MBA candidates. Journal of Business Strategy, 20(3), 30–34.

Grossman, M. (1999). On-line U. Scientific Amer-ican, 281, 41.

Hachigian, N. (2001). China’s cyber-strategy. For-eign Affairs, 80(2), 118-133.

Hara, N. (1998, October). Students’ perspectives in a Web-based distance education course. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Mid-Western Educational Research Associa-tion, Chicago.

Harden, R., & Crosby, J. (2000). AMEE guide no. 22: The good teacher is more than a lecturer— the twelve roles of the teacher. Medical Teacher, 22, 334–348.

Herther, N. K. (1997). Education over the Web: Distance learning and the information profes-sional. Online, 21(5), 63–71.

Hiltz, L. R., & Welman, B. (1997). Asynchro-nous learning networks as a virtual classroom. Communications of the ACM, 40(9), 44–49. Hitch, L., & Hirsch, D. (2001). Model training.

Journal of Academic Librarianship, 27(1), 15–20.

Holland, M. P. (1996). Collaborative technologies in inter-university instruction. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 47, 857–862.

Jamal, M. (1999). Job stress, type A behavior, and well being: A cross-cultural examination. Inter-national Journal of Stress Management, 6, 57–67.

Kedia, B. L., & Harveston, P. D. (1998). Transfor-mation of MBA programs: Meeting the chal-lenge of international competition. Journal of World Business, 33, 203–217.

Kerker, S. (2001). Confessions of a learning pro-gram dropout. Corporate University Review, 9(2), 2–6.

Klor de Alva, J. (2000). Remaking the academy. Educause, 35(2), 32–40.

Kolb, D. (2000). Learning places: Building, dwelling, thinking. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 34(1), 121–134.

Kuratko, D. F., Montagno, R. V., & Hornsby, J. S. (1990). Developing an intrapreneurial assess-ment instruassess-ment for an effective corporate entrepreneurial environment. Strategic Man-agement Journal, 11, 49–58.

Kwartler, D. (1998, December). Is distance learn-ing a financial bonanza? MBA Newsletter, 7, 6–10.

Lo Choi Yuet Ngor, A. (2001). The prospects for using the Internet in collaborative design edu-cation with China. Higher Education, 42(1), 47–61.

MacFarland, T. W. (1998). A comparison of final grades in courses when faculty concurrently taught the same course to campus-based and distance education students. Ft. Lauderdale, FL: Nova Southeastern University. (ERIC Doc-ument Reproduction Service No. 429476) MacLellan, C., & Dobson, J. (1997). Women,

ethics, and MBAs. Journal of Business Ethics, 16, 1201–1209.

Mack, A. M. (2001). I-shops see opportunity in Latin American market. Adweek, 42(3), 40. Madden, N. (2000). China tries hand at regulating

online ads. Advertising Age International, 22(7), 13.

March, T. (2000). Link like you mean it! Selecting Web sites to support intentional learning out-comes. Multimedia Schools, 7(2), 52–55. Meisel, S., & Marx, B. (1999). Screen to screen

versus face to face: Experiencing the differ-ences in management education. Journal of Management Education, 23, 719–731. Mioduser, D., Nachmias, R., Lahav, O., & Oren,

A. (2000). Web-based learning environments: Current pedagogical and technological state. Journal of Research on Computing in Educa-tion, 33(1), 55–76.

Moore, T. E. (1997). The corporate university: Transforming management education. Account-ing Horizons, 11(1), 77–85.

Nelson, G. E. (1997). Expectations of Internet education. Casper, WY: Caspar College. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. 411904)

Oblinger, D., & Kidwell, J. (2000). Distance learning: Are we being realistic? Educause, 35(3), 31–39.

Parasuraman, A. (2000). Technology readiness index (TRI): A multiple-item scale to measure readiness to embrace new technologies. Journal of Service Research,2, 307–320.

Parasuraman, A., & Grewal, D. (2000). The impact of technology on the quality-value-loyalty chain: A research agenda. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,28(1), 168–174.

Parnell, J. A. (2000). International graduate course delivery via the Internet: The case of business strategy in Mexico. Paper presented at the 2000 Academy of Business Education Annual Meeting, Hamilton,Bermuda. Parnell, J. A., & Carraher, S. (2003). The

Man-agement Education by Internet Readiness (MEBIR) scale: Developing a scale to assess one’s propensity for Internet-mediated manage-ment education. Journal of Management Edu-cation, 27, 431–446.

Peng, M. W., Lu, Y., Shenkar, O., & Wang, D. Y. L. (2001). Treasures in the China house: A review of management and organizational research on Greater China. Journal of Business Research, 52, 95–110.

Peter, J. P. (1979). Reliability: A review of psy-chometric basics and recent marketing prac-tices. Journal of Marketing Research, 16, 6–17. Quick, R., & Lieb, T. (2000). The heart field

proj-ect. THE Journal, 28(5), 41–46.

Quilter, S., & Chester, C. (2001). The relationship between Web-based conferencing and instruc-tional outcomes. International Journal of Instructional Media, 28(1), 13–22.

Rahm, D., & Reed, B. J. (1997). Going remote: The use of distance learning, the World Wide

Web, and the Internet in graduate programs of public affairs and administration. Public Pro-ductivity and Management Review, 20, 459–471.

Rennes, L., van, & Collis, B. (1998). User inter-face design for WWW-based courses: Building upon student evaluations. Paper presented at World Conference on Educational Multimedia & Hypermedia & World Conference on Educa-tional Telecommunications, Freidburg, Ger-many.

Rich, D., Pitman, A., & Gosper, M. (2000). Inte-grated IT-based geography teaching and learn-ing: A Macquarie University case study. Jour-nal of Geography in Higher Education, 24(1), 109–116.

Roberts, B. (1998). Training via the desktop. HRMagazine, 43(9), 98–104.

Robertson, L. J., & Stanforth, N. (1999). College students’ computer attitudes and interest in Web based distance education. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 91(3), 60–64. Ross, G. L., & Klug, M. G. (1999). Attitudes of

business college faculty and administrators toward distance education: A national survey. Distance Education, 20, 109–128.

Schwarzer, R., Mueller, J., & Greenglass, E. (1999). Assessment of perceived general self-efficacy on the Internet: Data collection in cyberspace. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 12, 145–161.

Sethi, V., & Carraher, S. (1993). Developing mea-sures for assessing the organizational impact of information technology: A comment on Mah-mood and Soon’s paper. Decision Sciences, 24, 867–877.

Shrivastava, P. (1999). Management classes as online learning communities. Journal of Man-agement Education, 23, 691–702.

Simonson, M., Schlosser, C., & Hanson, D. (1999). Theory and distance education: A New discussion. American Journal of Distance Edu-cation, 13(1), 60–75.

Siu, O. (2003). Job stress and job performance among employees in Hong Kong: The role of Chinese work values and organizational com-mitment. International Journal of Psychology, 38, 337–347.

Smith, D. E., & Duus, H. J. (2001). The power of e-learning in international business education.

Journal of Teaching in International Business, 13(2), 55–72.

Smith, P. L., & Dillon, C. L. (1999). Comparing distance learning and classroom learning: Con-ceptual considerations. American Journal of Distance Education, 13(2), 6–23.

Strauss, S. G. (1996). Getting a clue: Communi-cation media and information distribution effects on group process and performance. Small Group Research, 27(1), 115–142. Sweeney, M. T., & Oram, I. (1992). Information

technology for management education: The benefits and barriers. International Journal of Information Management, 12, 294–309. Taylor, J. (1996). The continental classroom:

Teaching labor studies on-line. Labor Studies Journal, 21, 19–38.

Thurston, C. W. (2000). Mexico invests in Internet banking. Global Finance, 14(12), 63–64. Top 10 strategies: Internet. (2001). Business

Mex-ico,10(12), 52–54.

Tysome, T. (2001). New learndirect leader looks at foundation-degree courses. Times Higher Education Supplement,1482, 5.

Wee, K. N. L., & Ramachandra, R. (2000). Cyber-buying in China, Hong Kong and Singapore: Tracking the who, where, why and what of online buying. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 28, 307–316. White, D., Rea, A., McHaney, R., & Sanchez, C.

(1998). Pedagogical methodology in virtual courses. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Decision Science Institute, Orlando, FL. Wo, C. M., & Pounder, J. S. (2000). Post-experi-ence management education and training in China. Journal of General Management, 26(2), 52–71.

Xie, J. L. (1996). Karasek’s model in the People’s Republic of China: Effects on job demands, control, and individual differences. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 1594–1618. Yang, D. Y. (2001). The great net of China:

Inter-net technology and governance in China. Har-vard International Review, 22(4), 64–69. Yee, C. M. (2001, July 9). In Asia, it’s not a

wide-open net. Wall Street Journal, p. B1.

Zhao, H. X. (2002). Rapid Internet development in China: A discussion of opportunities and constraints on future growth. Thunderbird International Business Review,44(1), 119–138.

APPENDIX

The Management Education by Internet Readiness (MEBIR) Scale

TECHNOLOGICAL MASTERY

TECH1 I generally have no problems downloading files and software via the Internet. TECH2 I consider my computer ability to be better than average.

TECH3 I get frustrated easily with technology. (R)

FLEXIBILITY OF COURSE DELIVERY

FLEX1 Taking an Internet course would allow me to arrange my work schedule more effectively.

FLEX2 Taking an Internet course could allow me to finish my degree more quickly. FLEX3 Taking an Internet course could allow me to take a class I would otherwise not

be able to take.

(appendix continues)

(appendix continued)

ANTICIPATED QUALITY OF COURSE

QUAL1 I would probably learn more from my fellow students in an Internet course than I would in a face-to-face course.

QUAL2 I would probably not learn as much in an Internet course as I would in a face-to-face course. (R)

QUAL3 I learn more effectively when I interact with people in a face-to-face setting. (R)

Note. (R) indicates items that were reverse-coded.