Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI Date: 12 January 2016, At: 17:54

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Assessing Faculty Beliefs About the Importance of

Various Marketing Job Skills

Michael R. Hyman & Jing Hu

To cite this article: Michael R. Hyman & Jing Hu (2005) Assessing Faculty Beliefs About the Importance of Various Marketing Job Skills, Journal of Education for Business, 81:2, 105-110, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.81.2.105-110

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.81.2.105-110

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 40

View related articles

ABSTRACT. The need to improve the

professional skills of those with marketing

degrees has spurred surveys of current

stu-dents, alumni, practitioners, and faculty

about the importance of various professional

skills; however, previous surveys of

market-ing faculty have focused only on computer

skills. To address this limitation, the goals of

this study were (a) to identify

marketing-related skills that students, alumni, and

prac-titioners believe to be important; (b) to assess

the importance that marketing faculty

cur-rently assign to these skills; and (c) to

deter-mine if faculty beliefs about these skills are

longitudinally stable. The results of two

orig-inal national surveys, fielded in 1995 and

2002, show that faculty view communication

and cognitive skills as relatively more

impor-tant than other skills and that faculty

mem-bers’ beliefs about the importance of

differ-ent skills have not changed since 1995. Also,

faculty beliefs fall into a stable structure of

five basic skills groups—management,

cog-nitive, communication, bridging, and

inter-personal—which can be used as a framework

to guide pedagogy and student assessment.

Copyright © 2005 Heldref Publications

fter completing college, most marketing majors search for jobs that require a set of skills that they should have acquired and honed throughout their education. It is unfor-tunate that some graduates lack the skills needed to perform these jobs. For example, although they believe their knowledge-related skills are more than adequate, some graduates report that they have inadequate technical and communications skills (Davis, Misra, & Van Auken, 2002). Moreover, com-pany recruiters report that soon-to-graduate students often lack adequate communication skills, planning and organization skills, and decision-mak-ing skills (McDaniel & White, 1993). As educators and mentors, marketing faculty are responsible for helping their students obtain required job skills. Thus, identifying the skills that marketing faculty should foster is important.

A skill is an underlying ability that can be refined through practice (Shipp, Lamb, & Mokwa, 1993). Through coursework and marketing-related extracurricular activities, marketing edu-cators help students acquire and develop professional skills that pertain to academ-ic and career success (Shipp et al., 1993). Although skill training is important, busi-ness schools in general and marketing programs in particular have been criti-cized for not developing the skills

deemed important by the business com-munity (Cheit, 1985; McDaniel & Hise, 1984a, 1984b; Stanton, 1988).

This study had three objectives. The first objective was to generate a com-prehensive list of professional market-ing skills. Through a review of pub-lished work summarizing surveys of marketing students, alumni, and practi-tioners, 26 such skills were identified. The second objective was to assess the importance that marketing faculty assign to these skills and whether their assessment has changed in the last sev-eral years. To achieve this objective, we conducted two original national sur-veys of U.S.-based marketing faculty. Because marketing faculty should have the most global perspective on (a) needed job skills, (b) the limitations of current students in these skill areas, and (c) the best pedagogical exercises to foster these skills, their assessment— previously limited to computer skills— should meaningfully augment the prior assessments of students, alumni, and practitioners. The third objective was to determine if a stable underlying struc-ture in faculty beliefs about necessary marketing skills exists. The existence of such a structure would provide fac-ulty and administrators with a clear framework for developing the best exercises and student assessment tools, the latter of clear interest to accrediting organizations like the Association to

Assessing Faculty Beliefs About the

Importance of Various Marketing Job Skills

MICHAEL R. HYMAN JING HU

NEW MEXICO STATE UNIVERSITY HOFSTRA UNIVERSITY LAS CRUCES, NEW MEXICO HEMPSTEAD, NEW YORK

A

Advance Collegiate Schools of Busi-ness (AACSB).

Previous Skills-Related Studies

Marketing scholars have tried to ascertain the most important general and business-specific skills for market-ing practitioners by surveymarket-ing several stakeholder groups: employers, alumni, students, and faculty. Unfortunately, the results of these scholars’ efforts have not yielded a clear consensus about the relative importance of many skills. Fur-thermore, all previous surveys of facul-ty ignored general skills, such as infor-mation gathering and problem solving.

Employer Surveys

Researchers have queried Fortune 500 executives (Court & Hyman, 1996), recruiters (McDaniel & White, 1993; Ursic & Hegstrom, 1985), and employ-ers (Hafer & Hoth, 1981; Kelley & Gaedeke, 1990) about critical skills for marketing practitioners. Recruiters and employers tended to rate oral and writ-ten communication, ability to collabo-rate, organization, and planning as very important skills but business-specific skills, such as marketing or financial modeling, as less important. Court and Hyman only studied computer skills, so no assessment of general skills by For-tune 500 executives is available.

Alumni Surveys

In surveys of alumni, researchers have polled undergraduate marketing (Davis et al., 2002; Ursic & Hegstrom, 1985) and nonmarketing (Davis et al.; King & Rawson, 1985) degree holders with several years of work experience. Such respondents, who understand workplace realities yet can easily recall their university instruction, generally rated oral and written communication and ability to collaborate as very impor-tant skills, but analytical and business-specific skills as less important.

Student Assessments

Published studies of current students entailed surveys of undergraduate mar-keting majors (Duke, 2002; Hafer & Hoth, 1981; Kelley & Gaedeke, 1990; Ursic & Hegstrom, 1985) and masters

of business administration students (Dacko, 2001). These students tended to rate oral and written communication, ability to collaborate, decision-making, leadership, planning, and organization as very important skills; they generally rated business-specific skills as mean-ingfully less important.

Faculty Assessments

Previous faculty studies entailed sur-veys of professors (Court & Hyman, 1996; Messina, Guiffrida, & Wood, 1991), marketing department chairper-sons (Turnquist, Bialaszewski, & Franklin, 1991), and business school deans (McNeeley & Berman, 1988). Although such respondents may have a more comprehensive and consistent per-spective, all previous faculty surveys were of limited scope. Court and Hyman, McNeeley and Berman, and Turnquist et al. only addressed students’ computer skills. Messina et al. focused on the gap between faculty and practi-tioner beliefs about content-knowledge requirements for entry-level industrial marketing jobs.

Consensus

Students, alumni, and employers tended to rate four general skills—oral communication, written communica-tion, decision making, and ability to col-laborate—as the most critical skills for marketing practitioners. They rated leadership, planning, and organizing of somewhat less importance and busi-ness-specific skills of much less impor-tance. However, the consensus was far from perfect. For example, even among skills they all considered important, stu-dents tended to rate some skills as less important and other skills as more important than did practitioners and alumni. Thus, the previous surveys do not yield a clear consensus about the relative importance of many profession-al skills.

Marketing degree programs, and their associated faculty, focus on widely applicable skills important for entry-level and higher entry-level jobs in most industries. In contrast, students, alumni, and employers tend to focus on industry and job-specific skills. As a result of their more universal perspectives, the

importance of various professional skills should differ less among faculty than among students, alumni, and employers. For example, recruiters who interviewed for different marketing positions rated several job skills of dif-ferent importance (McDaniel & White, 1993). Similarly, in one study of employers, many responses about skill importance were inconsistent (Kelley & Gaedeke, 1990). On skills required for entry-level industrial marketing jobs, faculty responses were more consistent than practitioner responses (Messina et al.). Thus, a comprehensive survey of faculty beliefs about necessary job skills for marketing practitioners could pro-vide clearer insights useful for peda-gogy design and assessment that are more readily generalized.

METHOD

In 1995 and 2002, we asked indepen-dent samples of U.S.-based marketing faculty to answer the same set of skills-related and personal profile questions. These two faculty samples and the research instrument they received are described below.

Two Samples

In 1995, we conducted the first survey via mail, using the 1995 American Mar-keting Association Membership Directo-ry as the sample frame. A systematic sample of 400 faculty members was drawn from this frame. The question-naire—a center-stapled, 21.6 x 17.8 cm booklet printed on standard white paper—and a one-page cover letter were mailed first class (with postal service stamps rather than metered postage) to the sample. A return envelope with postal service stamps was included. Reminder postcards were mailed 3 weeks after questionnaires were mailed. A total of 133 usable responses were received, representing a response rate of 33.2%.

In 2002, we conducted the second survey online. We sent an invitation e-mail, identifying the purpose of the survey and the link to the survey Web site, to roughly 3,500 U.S. marketing faculty. These marketing educators were either listed in the Prentice Hall Mar-keting Faculty Directory (Hasselback,

2001) or on the marketing department Web pages of the 716 U.S. institutions listed in that directory. Only professors and administrators were invited to par-ticipate; lecturers were excluded. Sever-al weeks later, we posted a request for U.S.-based faculty to participate in the survey on the Electronic Marketing (ELMAR) Listserv (elmar@ama.org), an international e-mail network for mar-keting academicians. This second request was meant to encourage partici-pation by faculty who mistook the opt-in e-mail for spam. Only 24 additional qualified respondents submitted ques-tionnaires after the ELMAR posting. It is impossible to know if any of these 24 respondents were motivated by the ELMAR posting, the original invitation, or both solicitations.

The e-mail invitations and ELMAR request induced 218 faculty members to complete the online questionnaire. Two respondents were eliminated from analysis because they failed to answer more than half the questions. Although low, the effective response rate—based on initial invitations—of 6.2% is acceptable given that response rates are lower for online surveys than for postal mail surveys (Schuldt & Totten, 1994; Tse, 1998; Weible & Wallace, 1998).

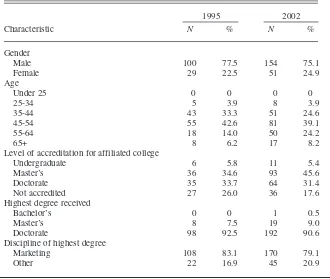

Table 1 shows a profile of the two samples on five basic characteristics: gender, age, level of accreditation for their affiliated colleges, highest degree received, and discipline of highest degree. Respondents in both samples tended to be male (roughly 75%), be at least 45 years old (roughly 70%), pos-sess terminal degrees in marketing (roughly 80%), and work at non-PhD-granting institutions (roughly 70%).

Although the sample frame and ques-tionnaire administration differed marked-ly between the two surveys, the profile data were quite similar; the only possibly noteworthy difference is the slightly lower incidence of respondents from non-AACSB-accredited institutions for the 2002 survey. Thus, no meaningful sys-tematic intersample bias was indicated.

The Instrument

The questionnaire included 26 items meant to assess marketing faculty beliefs about the general and business-specific

skills required for marketing practition-ers. We compiled these items from the 13 previously reviewed articles on the topic. We used a 7-point Likert-type scale rang-ing from 1 = not at all importantto 7 = extremely important. The scale was nega-tively skewed because prior literature suggested that most of the responses would be toward the positive endpoint and data from congruently unbalanced scales should produce cleaner factor analysis results by increasing interre-spondent variation (Hyman, 1996).

RESULTS

Univariate and factor analyses of the marketing skills ratings provided by respondents to the 1995 and 2002 sur-veys could indicate the stability of facul-ty skill ratings and the underlying struc-ture of faculty beliefs about those skills.

Univariate Analysis

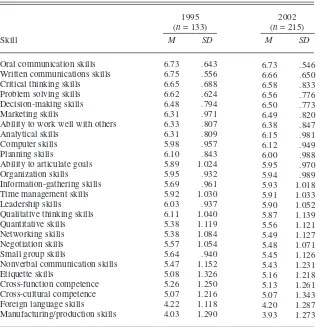

Table 2 summarizes faculty beliefs about the importance of 26 different marketing skills suggested by prior research. The skills are listed from high-est to lowhigh-est mean importance rating by respondents to the 2002 survey.

All skills were considered at least somewhat important (M> 4,SD= 0.55 to 1.34) by faculty surveyed in 1995 and 2002. Ten of the 26 skills were rated very important(M≥ approximately 6.0,

SD = 0.55 to 1.03) in both surveys; these skills were oral and written com-munication, critical thinking, problem solving, decision making, analytical skills, planning, marketing, computer skills, and working well with others. Table 2 shows that the standard devia-tions for the more important skills are meaningfully less than the standard deviations for the less important skills; thus, marketing faculty rated the most important skills more consistently than they rated the less important skills. For-eign language and manufacturing or production skills were clearly rated as least important; only these skills had mean ratings of less than 5 in both sur-veys (SD= 1.12 to 1.29).

Independent sample ttests were con-ducted to test the consistency in faculty beliefs at the beginning and end of this 7-year period. The results showed no significant difference (p> .05), except for a drop in the importance of qualita-tive-thinking skills,M = 6.12 vs. 5.87,

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Faculty Completing Surveys on Needed Job Skills for Marketing in 1995 and in 2002

1995 2002

Characteristic N % N %

Gender

Male 100 77.5 154 75.1

Female 29 22.5 51 24.9

Age

Level of accreditation for affiliated college

Undergraduate 6 5.8 11 5.4

Master’s 36 34.6 93 45.6

Doctorate 35 33.7 64 31.4

Not accredited 27 26.0 36 17.6

Highest degree received

Bachelor’s 0 0 1 0.5

Master’s 8 7.5 19 9.0

Doctorate 98 92.5 192 90.6

Discipline of highest degree

Marketing 108 83.1 170 79.1

Other 22 16.9 45 20.9

t(346) = −2.08,p= .04, and a rise in the importance of information gathering skills,M5.69 versus 5.93,t(346) = 2.20, p= .03. The drop in the importance of qualitative-thinking skills might be reflective of the increased availability and user-friendliness of software for statistical analysis and quantitative modeling, which encourages their use by even the minimally computer liter-ate. The rise in the importance of infor-mation-gathering skills might be reflec-tive of the increased quality and quantity of online data and Internet search engines. Regardless, to identify a consistent latent structure of important skills across the two survey administra-tions, these two items were dropped from subsequent analysis.

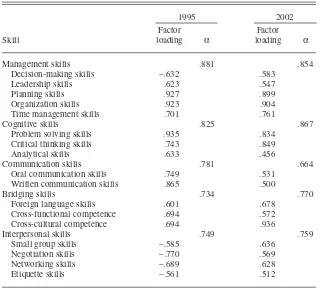

Factor Analysis

Table 3 summarizes the results of maximum likelihood factor analyses conducted separately on the two data

sets, with a focus on the common ance associated with individual vari-ables. The results show a common latent structure for marketing faculty beliefs about the skills needed by successful marketing practitioners. For both the 1995 and 2002 data sets, retained items had factor loadings of 0.50 or above. Based on the pattern of items and load-ings, the following factors seemed to emerge: management skills, cognitive skills, communication skills, bridging skills, and interpersonal skills.

Management skills include decision-making skills, leadership skills, planning skills, organization skills, and time-man-agement skills. Most of these skills were rated as important in previous studies: decision making in Dacko (2001), Duke (2002), McDaniel and White (1993), and Ursic and Hegstrom (1985); leadership in Dacko, Duke, Hafer and Hoth (1981), Kelley and Gaedeke (1990), and McDaniel and White; and planning and organization in Dacko, McDaniel and

White, and Ursic and Hegstrom. Cogni-tive skills have been identified as prob-lem-solving skills (Davis et al., 2002; Kelley & Gaedeke), critical-thinking skills (Braun, 2004), and analytical skills (Dacko; Davis et al.; Duke; McDaniel & White). Communication skills (oral and written) were assessed as important in almost all previous studies (Dacko; Davis et al.; Duke; Hafer & Hoth; Hite, Bel-lizzi, & McKinley, 1987; Kelley & Gaedeke; King & Rawson, 1985; McDaniel & White). Bridging skills (i.e., foreign language skills, cross-functional competence, and cross-cultural compe-tence; Dudley & Dudley, 1995) and inter-personal skills (i.e., small group skills, negotiation skills, networking skills, and etiquette skills) are the two sets of skills considered less important by practition-ers and alumni than by marketing faculty. Table 3 shows that the factor loadings for the interpersonal skills items are negative for the 1995 data set and posi-tive for the 2002 data set. This sign change could be an artifact of factor rotation or suggest a shift in faculty opinion. To resolve this ambiguity, we calculated composite measures for each set of related skills that loaded on a given factor, where each respondent’s score was the sum of the related items divided by the number of items. We then calculated correlation matrices for these five composite measures for both data sets. If the pattern—signs and magni-tudes—of correlations in these matrices was similar, then the sign change was an artifact of factor rotation. In fact, the sign changes for the four skills that load on the interpersonal skills factor repre-sented such an artifact.

Cronbach’s alpha for all dimensions was acceptable (α > .70) except for communication skills in the 2002 sur-vey (α= .664). The reason for the rela-tively low reliability of this scale was that another item, ability to work well with others, also loaded highly on com-munication skills, but it was deleted from the factor structure because it did not load highly on this dimension for the earlier survey (α= .3).

Univariate F Tests

To test whether faculty beliefs were related to gender, age, or type of institu-tion (AACSB accredited or not), we TABLE 2. Faculty Ratings of Marketing Skill Importance for 1995 and

2002 Surveys

1995 2002

(n= 133) (n= 215)

Skill M SD M SD

Oral communication skills Written communications skills Critical thinking skills Problem solving skills Decision-making skills Marketing skills

Ability to work well with others Analytical skills

Computer skills Planning skills

Ability to articulate goals Organization skills Information-gathering skills Time management skills Leadership skills Qualitative thinking skills Quantitative skills Networking skills Negotiation skills Small group skills

Nonverbal communication skills Etiquette skills

Cross-function competence Cross-cultural competence Foreign language skills Manufacturing/production skills

conducted univariate Ftests. The results revealed no significant difference (p > .05) on gender or age. However, for respondents to the 2002 survey, comput-er skills wcomput-ere rated as more important by faculty from AACSB-accredited institutions than from non-AACSB-accredited institutions.

Wilks’ lamda is a measure of the vari-ance in the dependent measures not accounted for by group membership. Here, Wilks’ lambda for computer skills was 0.774; that is, only a small part (roughly 23%) of the variance in the believed importance of this skill was explained by faculty affiliation with an AASCB-accredited institution. The remaining variance was attributable to a lack of consensus among respondents in each group or measurement error (Messina, Guiffrida, & Wood, 1991). Furthermore, a ttest showed no differ-ence in beliefs about the importance of computer skills between faculty at AACSB-accredited and non-AACSB-accredited institution,t(346) = 1.434,p

= .16. Thus, beliefs about the impor-tance of these five basic skills seem unrelated to a faculty member’s gender, age, or institutional accreditation.

DISCUSSION

Although the social, political, eco-nomic, and technological environments have changed dramatically since 1995, marketing faculty beliefs about the pro-fessional skills their students should develop have remained stable. This invariance suggests that there are some timeless skills that marketing faculty should foster in their students. The results of two original surveys of mar-keting faculty—conducted in 1995 and 2002—indicate that communication and cognitive skills are consistently viewed as most important, and bridging skills are consistently viewed as least impor-tant.

A stable latent structure for profes-sional skills of marketing practitioners can provide a clear framework for

developing answers to questions such as the following:

1. How should marketing educators incorporate professional skills training into their teaching objectives?;

2. What exercises—both course-relat-ed and extracurricular—would be most effective in fostering professional mar-keting skills?; and

3. What tools are needed to assess the adequate attainment of professional marketing skills?

The answers to such questions can help marketing educators incorporate professional skills into their individual courses and degree programs more effi-ciently and effectively, make better use of educational resources to improve dent skills, and better prepare their stu-dents for the business world. Focusing on the basic skills sets—management skills, cognitive skills, communication skills, bridging skills, and interpersonal skills—rather than numerous and seem-ingly different individual skills, will facilitate course and degree program changes. This structure can also be used to develop tools needed to assess the adequate attainment of professional marketing skills.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Shaun McQuitty and Tom Pilon for their helpful advice.

NOTE

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Michael R. Hyman, Wells Fargo Professor of Marketing, College of Business, New Mexico State University, Box 30001, Dept. 5280, Las Cruces, New Mexico 88003-8001. E-mail: mhyman@nmsu.edu.

REFERENCES

American Marketing Association. American Mar-keting Association Membership Directory. (1995). Chicago, IL: Author.

Braun, N. M. (2004). Critical thinking in the busi-ness curriculum. Journal of Education for Busi-ness,79, 232–236.

Cheit, E. F. (1985, Spring). Business schools and their critics. California Management Review, 27(3), 43–61.

Court, B., & Hyman, M. R. (1996). The under-graduate marketing curriculum and computing skills: An action grid analysis. In E. W. Stuart, D. J. Ortinau, & E. M. Moore (Eds.), Market-ing: Moving toward the 21st century. SMA con-ference proceedings(pp. 211–216). Rock Hill, SC: Winthrop University School of Business Administration.

Dacko, S. (2001, December). Narrowing skills TABLE 3. Factor Analysis of Fundamental Marketing Skills for 1995 and

2002 Surveys

1995 2002

Factor Factor

Skill loading α loading α

Management skills .881 .854

Decision-making skills –.632 .583

Leadership skills .623 .547

Planning skills .927 .899

Organization skills .923 .904

Time management skills .701 .761

Cognitive skills .825 .867

Problem solving skills .935 .834 Critical thinking skills .743 .849

Analytical skills .633 .456

Communication skills .781 .664

Oral communication skills .749 .531 Written communication skills .865 .500

Bridging skills .734 .770

Foreign language skills .601 .678 Cross-functional competence .694 .572 Cross-cultural competence .694 .936

Interpersonal skills .749 .759

Small group skills –.585 .636

Negotiation skills –.770 .569

Networking skills –.689 .628

Etiquette skills –.561 .512

Note. Qualitative skills and information gathering skills were excluded because of significant dif-ferences in data between 1995 and 2002. Only items that were grouped similarly are included in this table.

development gaps in marketing and MBA pro-grams: The role of innovative technologies for distance learning. Journal of Marketing Educa-tion, 23(3), 228–239.

Davis, R., Misra, S., & Van Auken, S. (2002, December). A gap analysis approach to market-ing curriculum assessment: A study of skills and knowledge. Journal of Marketing Educa-tion, 24(3), 218–224.

Dudley, S. C., & Dudley, L. W. (1995). New direc-tions for the business curriculum. Journal of Education for Business, 70, 305–310. Duke, C. R. (2002, December). Learning

out-comes: Comparing student perceptions of skill level and importance. Journal of Marketing Education, 24(3), 203–217.

Hafer, J. C., & Hoth, C. C. (1981, Spring). Grooming your marketing students to match the employer’s ideal job candidate. Journal of Mar-keting Education, 3(1), 15–19.

Hasselback, J. R. (2001). Prentice Hall marketing faculty directory. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Hite, R. E., Bellizzi, J. A., & McKinley, J. W. (1987, Summer). Attitudes of marketing stu-dents with regard to communications skills. Journal of Marketing Education, 9(2), 20–24. Hyman, M. R. (1996). A critique and revision of

the Multidimensional Ethics Scale. Journal of Empirical Generalisations in Marketing

Sci-ence,1, 1–35. Retrieved from http://www.emp-gens.com/A/ethics/ethics.html

Kelley, C. A., & Gaedeke, R. M. (1990, Fall). Stu-dent and employer evaluation of hiring criteria for entry-level marketing positions. Journal of Marketing Education, 12(3), 64–71.

King, R. H., & Rawson, R. (1985, Summer). An assessment of employee satisfaction with undergraduate business-administration educa-tion. Journal of Marketing Education, 7(2), 65–73.

McDaniel, S. W., & Hise, R. T. (1984a, Summer). Shaping the marketing curriculum: The CEO perspective. Journal of Marketing Education, 15(2), 27–32.

McDaniel, S. W., & Hise, R. T. (1984b, Fall). The marketing curriculum: A decade of change. Journal of Marketing Education, 15(3), 2–8. McDaniel, S. W., & White, J. C. (1993, Fall). The

quality of the academic preparation of under-graduate marketing majors: An assessment by company recruiters. Marketing Education Review, 3(3), 9–16.

McNeeley, B. J., & Berman, B. (1988, Fall). Usage of microcomputer software in AACSB-accredited undergraduate and graduate market-ing programs. Journal of Marketing Education, 10(3), 84–93.

Messina, M. J., Guiffrida, A. L., & Wood, G. R. (1991). Faculty/practitioner differences: Skills

needed for industrial marketing entry positions. Industrial Marketing Management, 20, 17–21. Schuldt, B. A., & Totten, J. W. (1994, Winter).

Electronic mail vs. mail survey response rates. Marketing Research,6(1), 36–39.

Shipp, S., Lamb, C. W., Jr., & Mokwa, M. P. (1993, Fall). Developing and enhancing mar-keting students’ skills: Written and oral com-munication, intuition, creativity, and computer usage. Marketing Education Review, 3(3), 2–8.

Stanton, W. J. (1988, Summer). It is time to restructure marketing in academia. Journal of Marketing Education, 10(2), 2–7.

Tse, A. C. B. (1998, October). Comparing the response rate, response speed and response quality of two methods of sending question-naires: E-mail vs. mail. Journal of the Market Research Society, 40(4), 353–361.

Turnquist, P. H., Bialaszewski, D. W., & Franklin, L. (1991, Spring). The undergraduate market-ing curriculum: A descriptive overview. Journal of Marketing Education, 13(1), 40–46. Ursic, M., & Hegstrom, C. (1985, Summer). The

views of marketing recruiters, alumni and stu-dents about curriculum and course structure. Journal of Marketing Education, 7(2), 21–27. Weible, R., & Wallace, J. (1998, Fall). Cyber

research: The impact of the internet on data col-lection. Marketing Research, 10(3), 19–31.